Assessing Active Living Potential: Case Study of Jacksonville, Florida

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Grocery stores: supermarkets, neighborhood or community shopping centers

- Schools: public schools or colleges

- Public facilities: facilities operated by municipalities other than public schools, colleges, military, or correctional facilities

- Recreational facilities: theaters, auditoriums, or sport facilities

- Parks: public parks

- Public spaces: outdoor recreational spaces other than parks

3. Results

3.1. GIS Modeling Results

3.2. Applicaton of the GIS Modeling Results

3.2.1. Which Residential Types Have Higher (or Lower) Chances of Involving Physical Activity?

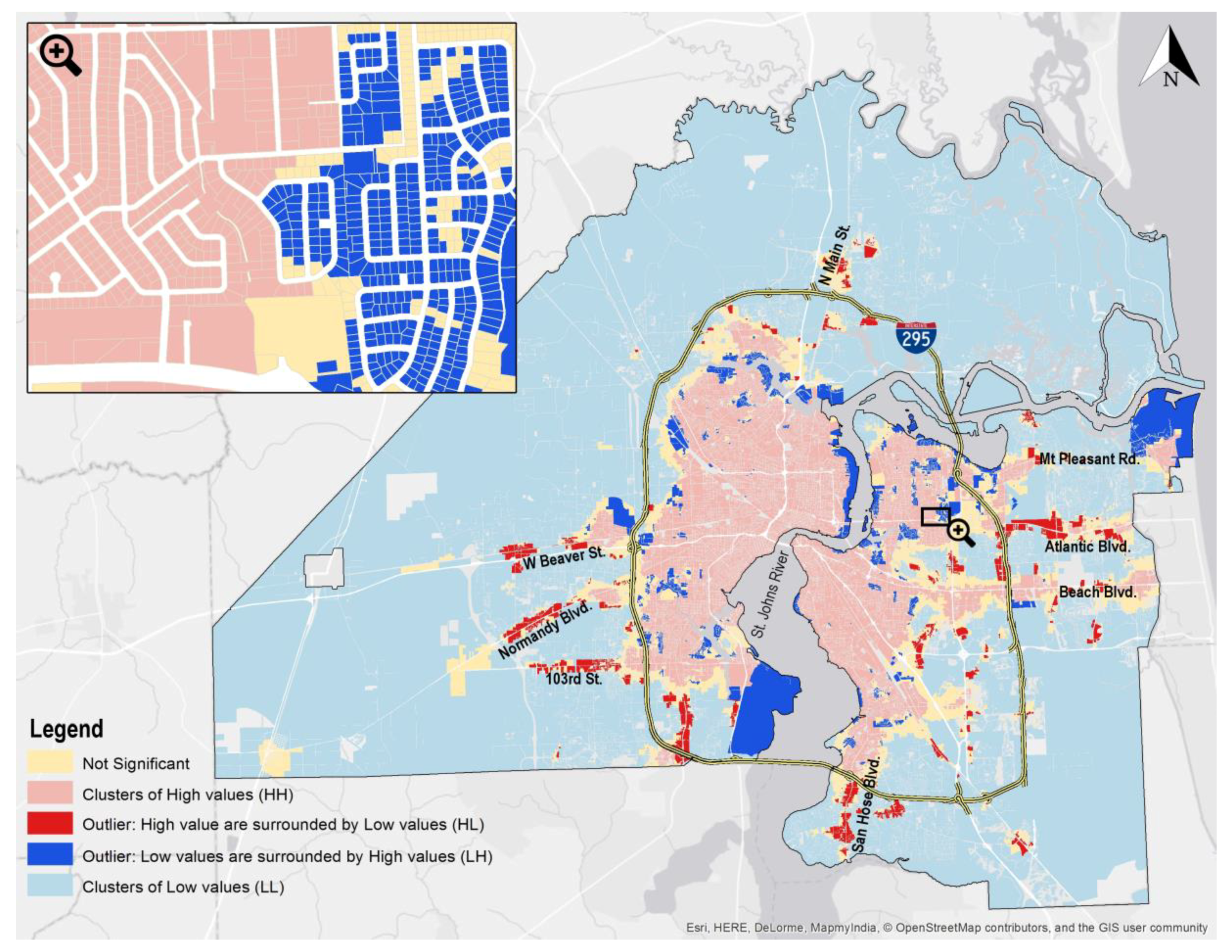

3.2.2. Which Residential Types Are Highly Clustered with Higher Opportunities for Active Living?

4. Discussion

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Maps of Trends in Diabetes and Obesity. 2018. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/statistics/slides/maps_diabetesobesity_trends.pptx (accessed on 28 May 2018).

- Eckel, R.H.; Kahn, S.E.; Ferrannini, E.; Goldfine, A.B.; Nathan, D.M.; Schwartz, M.W.; Smith, R.J.; Smith, S.R. Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes: What can be unified and what needs to be individualized? Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 1424–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sullivan, P.W.; Morrato, E.H.; Ghushchyan, V.; Wyatt, H.R.; Hill, J.O. Obesity, Inactivity, and the Prevalence of Diabetes and Diabetes-Related Cardiovascular Comorbidities in the U.S., 2000–2002. Diabetes Care 2005, 28, 1599–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aytur, S.A.; Rodriguez, D.A.; Evenson, K.R.; Catellier, D.J.; Rosamond, W.D. Promoting Active Community Environments Through Land Use and Transportation Planning. Am. J. Health Promot. 2007, 21, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, L.; Kerr, J.; Chapman, J.; Sallis, J. Urban form relationships with walk trip frequency and distance among youth. Am. J. Health Promot. 2007, 21, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, D.A.; Sehgal, A.; Williamson, S.; Golinelli, D.; Lurie, N.; McKenzie, T.L. Contribution of Public Parks to Physical Activity. Am. J. Public Health 2007, 97, 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handy, S.L.; Xinyu, C.; Mokhtarian, P.L. The Causal Influence of Neighborhood Design on Physical Activity within the Neighborhood: Evidence from Northern California. Am. J. Health Promot. 2008, 22, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaczynski, A.T.; Potwarka, L.R.; Saelens, B.E. Association of Park Size, Distance, and Features with Physical Activity in Neighborhood Parks. Am. J. Public Health 2008, 98, 1451–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Zetina, J.; Lee, H.; Friis, R. The link between obesity and the built environment. Evidence from an ecological analysis of obesity and vehicle miles of travel in California. Health Place 2006, 12, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sturm, R.; Cohen, D.A. Suburban sprawl and physical and mental health. Public Health 2004, 118, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Squires, G.D. Urban Sprawl: Causes, Consequences, & Policy Responses; Urban Institute Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, R.P.; Hynes, H.P. Obesity, physical activity, and the urban environment: Public health research needs. Environ. Health 2006, 5, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- City of New York. Active Design Guidelines: Promoting Physical Activity and Health in Design. 2010; pp. 1–135. Available online: https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/planning/download/pdf/plans-studies/active-design-guidelines/adguidelines.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2018).

- Frank, L.D.; Andresen, M.A.; Schmid, T.L. Obesity relationships with community design, physical activity, and time spent in cars. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2006, 27, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, L.D.; Sallis, J.F.; Conway, T.L.; Chapman, J.E.; Saelens, B.E.; Bachman, W. Many Pathways from Land Use to Health. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2006, 72, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownson, R.C.; Hoehner, C.M.; Day, K.; Forsyth, A.; Sallis, J.F. Measuring the Built Environment for Physical Activity: State of the Science. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 36, S99–S123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mumford, K.G.; Contant, C.K.; Weissman, J.; Wolf, J.; Glanz, K. Changes in Physical Activity and Travel Behaviors in Residents of a Mixed-Use Development. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 41, 504–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morland, K.; Wing, S.; Diez Roux, A. The contextual effect of the local food environment on residents’ diets: The atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Am. J. Public Health 2002, 92, 1761–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallis, J.F.; Glanz, K. Physical Activity and Food Environments: Solutions to the Obesity Epidemic. Milbank Q. 2009, 87, 123–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, N.C. Critical Factors for Active Transportation to School among Low-Income and Minority Students: Evidence from the 2001 National Household Travel Survey. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008, 34, 341–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babey, S.H.; Hastert, T.A.; Yu, H.; Brown, E.R. Physical Activity Among Adolescents: When Do Parks Matter? Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008, 34, 345–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coutts, C. Greenway accessibility and physical-activity behavior. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2008, 35, 552–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles-Corti, B.; Broomhall, M.H.; Knuiman, M.; Collins, C.; Douglas, K.; Ng, K.; Lange, A.; Donovan, R.J. Increasing walking: How important is distance to, attractiveness, and size of public open space? Am. J. Prev. Med. 2005, 28, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, L.V.; Diez Roux, A.V.; Evenson, K.R.; McGinn, A.P.; Brines, S.J. Availability of Recreational Resources in Minority and Low Socioeconomic Status Areas. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008, 34, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierce, J.; Denison, A.; Arif, A.; Rohrer, J. Living near a trail is associated with increased odds of walking among patients using community clinics. J. Community Health 2006, 31, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, D.E.; Sallis, J.F.; Conway, T.L.; Cain, K.L.; McKenzie, T.L. Active Transportation to School over 2 Years in Relation to Weight Status and Physical Activity. Obesity 2006, 14, 1771–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besser, L.M.; Dannenberg, A.L. Walking to Public Transit: Steps to Help Meet Physical Activity Recommendations. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2005, 29, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saelens, B.E.; Handy, S.L. Built Environment Correlates of Walking: A Review. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2008, 40, S550–S566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, J.D.; Rodkey, L.; Ray, R.; Saelens, B. Do Not Forget About Public Transportation: Analysis of the Association of Active Transportation to School among Washington, DC Area Children with Parental Perceived Built Environment Measures. J. Phys. Act. Health 2018, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boarnet, M.G.; Forsyth, A.; Day, K.; Oakes, J.M. The Street Level Built Environment and Physical Activity and Walking: Results of a Predictive Validity Study for the Irvine Minnesota Inventory. Environ. Behav. 2011, 43, 735–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Cervero, R.; Kockelman, K. Travel demand and the 3Ds: Density, diversity, and design. Transp. Res. Part D 1997, 2, 199–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, G.K.W.; Van Niel, K.P.; Giles-Corti, B.; Knuiman, M. Accessibility and connectivity in physical activity studies: The impact of missing pedestrian data. Prev. Med. 2008, 46, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyler, A.A.; Brownson, R.C.; Bacak, S.J.; Housemann, R.A. The epidemiology of walking for physical activity in the United States. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35, 1529–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, L.D.; Schmid, T.L.; Sallis, J.F.; Chapman, J.; Saelens, B.E. Linking objectively measured physical activity with objectively measured urban form: Findings from SMARTRAQ. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2005, 28, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon-Larsen, P.; Nelson, M.C.; Page, P.; Popkin, B.M. Inequality in the Built Environment Underlies Key Health Disparities in Physical Activity and Obesity. Pediatrics 2006, 117, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, D. Neighborhood and Individual Factors in Activity in Older Adults: Results from the Neighborhood and Senior Health Study. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2008, 16, 144–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, J.A.; Wilson, D.K.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Bowles, H.; Mixon, G. Perceptions of Neighborhood Sidewalks on Walking and Physical Activity Patterns in a Southeastern Community in the US. J. Phys. Act. Health 2006, 3, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dill, J. Bicycling for Transportation and Health: The Role of Infrastructure. J. Public Health Policy 2009, 30, S95–S110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pucher, J.; Buehler, R. Making cycling irresistible: Lessons from the Netherlands, Denmark and Germany. Transp. Rev. 2008, 28, 495–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, D.T.; Aldstadt, J.; Whalen, J.; Melly, S.J.; Gortmaker, S.L. Validation of Walk Score® for Estimating Neighborhood Walkability: An Analysis of Four US Metropolitan Areas. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2011, 8, 4160–4179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, M.; Shah, B.R.; Maclagan, L.C.; Rezai, M.; Austin, P.C.; Tu, J.V. Walk Score® and the prevalence of utilitarian walking and obesity among Ontario adults: A cross-sectional study. Health Rep. 2015, 26, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Witten, K.; Pearce, J.; Day, P. Neighbourhood Destination Accessibility Index: A GIS Tool for Measuring Infrastructure Support for Neighbourhood Physical Activity. Environ. Plan. A 2011, 43, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiravian, F.; Derrible, S.; Ijaz, F. Development and application of the Pedestrian Environment Index (PEI). J. Transp. Geogr. 2014, 39, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazier, R.H.; Creatore, M.I.; Weyman, J.T.; Fazli, G.; Matheson, F.I.; Gozdyra, P.; Moineddin, R.; Shriqui, V.K.; Booth, G.L. Density, Destinations or Both? A Comparison of Measures of Walkability in Relation to Transportation Behaviors, Obesity and Diabetes in Toronto, Canada. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e85295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koohsari, M.J.; Owen, N.; Cerin, E.; Giles-Corti, B.; Sugiyama, T. Walkability and walking for transport: Characterizing the built environment using space syntax. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2016, 13, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saelens, B.E.; Sallis, J.F.; Black, J.B.; Chen, D. Neighborhood-based differences in physical activity: An environment scale evaluation. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 1552–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Story, M.; Giles-Corti, B.; Yaroch, A.L.; Cummins, S.; Frank, L.D.; Huang, T.T.; Lewis, L.B. Work Group IV: Future Directions for Measures of the Food and Physical Activity Environments. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 36, S182–S188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnosed Diabetes Prevalence County Estimates. 2018. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/atlas/obesityrisk/dmprev_xls/Florida.xlsx (accessed on 28 May 2018).

- Carr, M.H.; Zwick, P.D. Smart Land-Use Analysis: The LUCIS Model Land-Use Conflict Identification Strategy; ESRI Press: Redlands, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Manaugh, K.; Kreider, T. What is mixed use? Presenting an interaction method for measuring land use mix. J. Transp. Land Use 2013, 6, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A. Modeling Suitability, Movement, and Interaction; ESRI Press: Redlands, CA, USA, 2012; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Elaalem, M.; Comber, A.; Fisher, P. A Comparison of Fuzzy AHP and Ideal Point Methods for Evaluating Land Suitability. Trans. GIS 2011, 15, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environmental Systems Research Institute (ESRI). Cluster and Outlier Analysis (Anselin Local Moran’s I). 2018. Available online: http://pro.arcgis.com/en/pro-app/tool-reference/spatial-statistics/cluster-and-outlier-analysis-anselin-local-moran-s.htm (accessed on 28 May 2018).

- Christian, H.E.; Bull, F.C.; Middleton, N.J.; Knuiman, M.W.; Divitini, M.L.; Hooper, P.; Amarasinghe, A.; Giles-Corti, B. How important is the land use mix measure in understanding walking behaviour? Results from the RESIDE study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grasser, G.; Stronegger, W.; Titze, S.; Van Dyck, D. Objectively measured walkability and active transport and weight-related outcomes in adults: A systematic review. Int. J. Public Health 2013, 58, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajna, S.; Dasgupta, K.; Joseph, L.; Ross, N.A. A call for caution and transparency in the calculation of land use mix: Measurement bias in the estimation of associations between land use mix and physical activity. Health Place 2014, 29, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handy, S.L.; Niemeier, D.A. Measuring accessibility: An exploration of issues and alternatives. Environ. Plan. A 1997, 29, 1175–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, W.G. How Accessibility Shapes Land Use. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1959, 25, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, H.J. Place-Based versus People-Based Accessibility. Access to Destinations; Levinson, D.M., Krizek, K.J., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2005; pp. 63–89. [Google Scholar]

- Neutens, T.; Versichele, M.; Schwanen, T. Arranging place and time: A GIS toolkit to assess person-based accessibility of urban opportunities. Appl. Geogr. 2010, 30, 561–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, R.; Handy, S. Measuring the Unmeasurable: Urban Design Qualities Related to Walkability. J. Urban Des. 2009, 14, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwek, L.; Joinson, A.; Morvan, J. The use of self-monitoring solutions amongst cyclists: An online survey and empirical study. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2015, 77, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.S.; Foschini, L.; Kurtzman, G.W.; Zhu, J.; Wang, W.; Rareshide, C.A.L.; Zbikowski, S.M.; Zhu, J.; Wang, W. Using Wearable Devices and Smartphones to Track Physical Activity: Initial Activation, Sustained Use, and Step Counts Across Sociodemographic Characteristics in a National Sample. Ann. Intern. Med. 2017, 167, 755–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Residential Type | Number of Parcels (%) | Descriptive Statistics * | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | Mdn | LQ | UQ | Min | Max | SD | ||

| Single Family | 234,844 (80.23%) | 4.554 | 4.487 | 3.316 | 5.793 | 0.294 | 8.841 | 1.504 |

| Condominium | 21,420 (7.32%) | 4.869 | 4.836 | 3.628 | 5.743 | 2.195 | 8.623 | 1.262 |

| Multifamily | 5127 (1.75%) | 6.087 | 6.367 | 5.603 | 7.017 | 0.282 | 8.849 | 1.398 |

| Mobile Home | 9648 (3.30%) | 3.528 | 3.316 | 2.467 | 4.465 | 0.299 | 8.451 | 1.382 |

| Boarding Home | 8 (0.00%) | 6.482 | 7.140 | 6.466 | 7.409 | 2.043 | 7.782 | 1.876 |

| Retirement Home | 24 (0.01%) | 5.289 | 5.170 | 3.944 | 6.575 | 2.524 | 7.462 | 1.457 |

| Cooperative | 121 (0.04%) | 7.293 | 7.274 | 7.245 | 7.274 | 7.157 | 7.745 | 0.119 |

| Vacant Residential | 21,506 (7.35%) | 4.369 | 4.207 | 2.753 | 5.942 | 0.298 | 8.519 | 1.767 |

| Grand Total | 292,698 (100.00%) | 4.553 | 4.501 | 3.286 | 5.803 | 0.282 | 8.849 | 1.535 |

| Residential Type | Total Number of Parcels | Number of Parcels by Cluster & Outlier Type * | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HH | HL | LH | LL | NS | ||

| Single Family | 234,844 (100%) | 89,711 (38.20%) | 3501 (1.49%) | 8731 (3.72%) | 96,693 (41.17%) | 36,208 (15.42%) |

| Condominium | 21,420 (100%) | 5920 (27.64%) | 39 (0.18%) | 116 (0.54%) | 5303 (24.76%) | 10,042 (46.88%) |

| Multifamily | 5127 (100%) | 4132 (80.59%) | 87 (1.70%) | 66 (1.29%) | 534 (10.42%) | 308 (6.00%) |

| Mobile Home | 9648 (100%) | 1230 (12.75%) | 328 (3.40%) | 109 (1.13%) | 6601 (68.42%) | 1380 (14.30%) |

| Boarding Home | 8 (100%) | 7 (87.50%) | - | - | 1 (12.50%) | - |

| Retirement Home | 24 (100%) | 11 (45.83%) | 3 (12.50%) | - | 6 (25.00%) | 4 (16.67%) |

| Cooperative | 121 (100%) | 121 (100.00%) | - | - | - | - |

| Vacant Residential | 21,506 (100%) | 7996 (37.18%) | 306 (1.42%) | 415 (1.93%) | 10,206 (47.46%) | 2539 (12.01%) |

| Grand Total | 292,698 (100%) | 109,128 (37.28%) | 4264 (1.46%) | 9437 (3.23%) | 119,344 (40.77%) | 50,525 (17.26%) |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Noh, S. Assessing Active Living Potential: Case Study of Jacksonville, Florida. Urban Sci. 2018, 2, 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci2020044

Noh S. Assessing Active Living Potential: Case Study of Jacksonville, Florida. Urban Science. 2018; 2(2):44. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci2020044

Chicago/Turabian StyleNoh, Soowoong. 2018. "Assessing Active Living Potential: Case Study of Jacksonville, Florida" Urban Science 2, no. 2: 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci2020044

APA StyleNoh, S. (2018). Assessing Active Living Potential: Case Study of Jacksonville, Florida. Urban Science, 2(2), 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci2020044