Sense of Coherence Is Associated with Functional Impairment in Individuals Diagnosed with ADHD

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. ADHD, Antisocial Behavior, and Emotional Distress

1.2. Protective and Risk Factors Predicting ADHD-Related Functional Impairment

1.2.1. Factors Predicting ADHD-Related Antisocial Behavior

1.2.2. Factors Predicting ADHD-Related Mental Health Problems

1.3. Sense of Coherence

1.4. SOC as a Protective Factor Predicting ADHD-Related Functional Impairment

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Antisocial Behavior

2.2.2. Mental Health

2.2.3. Sense of Coherence

2.2.4. ADHD Symptoms

2.2.5. Socio-Demographic Characteristics

2.3. Analytic Approach

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Correlations

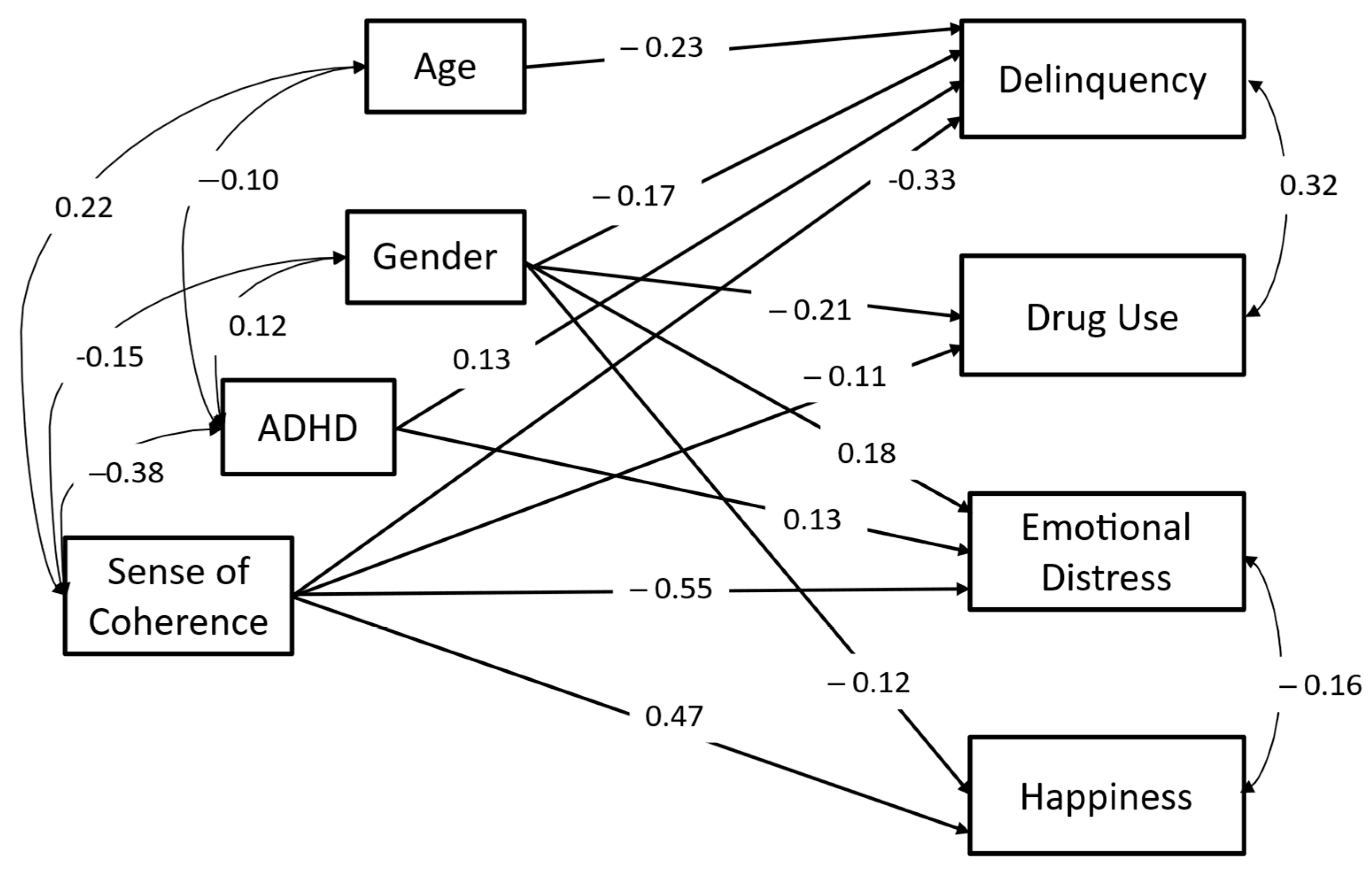

3.3. Path Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Research Contribution and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Faraone, S.V.; Banaschewski, T.; Coghill, D.; Zheng, Y.; Biederman, J.; Bellgrove, M.A.; Newcorn, J.H.; Gignac, M.; Saud, N.M.A.; Manor, I.; et al. The world federation of ADHD international consensus statement: 208 evidence-based conclusions about the disorder. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 128, 789–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Lorenzo, R.; Balducci, J.; Poppi, C.; Arcolin, E.; Cutino, A.; Ferri, P.; D’Amico, R.; Filippini, T. Children and adolescents with ADHD followed up to adulthood: A systematic review of long-term outcomes. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2021, 33, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kooij, J.J.S.; Bijlenga, D.; Salerno, L.; Jaeschke, R.; Bitter, I.; Balazs, J.; Thome, J.; Dom, G.; Kasper, S.; Filipe, C.N.; et al. Updated European Consensus Statement on diagnosis and treatment of adult ADHD. Eur. Psychiatry 2019, 56, 14–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dayan, H.; Shoham, R.; Berger, I.; Khoury-Kassabri, M.; Pollak, Y. Features of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and antisocial behaviour in a general population-based sample of adults. Crim. Behav. Ment. Health 2023, 33, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.R.; Bau, C.H.D.; Silva, K.L.D.; Callegari-Jacques, S.M.; Salgado, C.A.I.; Fischer, A.G.; Victor, M.M.; Sousa, N.O.; Karam, R.G.; Rohde, L.A.; et al. The burdened life of adults with ADHD: Impairment beyond comorbidity. Eur. Psychiatry 2012, 27, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr-Jensen, C.; Bisgaard, C.M.; Boldsen, S.K.; Steinhausen, H.C. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in childhood and adolescence and the risk of crime in young adulthood in a Danish nationwide study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2019, 58, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubiner, H.; Katragadda, S. Overview of epidemiology, clinical features, genetics, neurobiology, and prognosis of adolescent attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Adolesc. Med. State Art Rev. 2008, 19, 209–215. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, T.J.; Biederman, J.; Mick, E. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Diagnosis, lifespan, comorbidities, and neurobiology. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2007, 32, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.S.; Groves, N.B.; Marsh, C.L.; Miller, C.E.; Richmond, K.P.; Kofler, M.J. Are there resilient children with ADHD? J. Atten. Disord. 2021, 26, 643–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duh-Leong, C.; Fuller, A.; Brown, N.M. Associations between family and community protective factors and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder outcomes among US children. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2020, 41, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvorsky, M.R.; Langberg, J.M. A review of factors that promote resilience in youth with adhd and adhd symptoms. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 19, 368–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freire, J.V.C.; Cerqueira, R.A.; Sousa, D.F.; Novaes, J.F.A.; Farias, T.M.; Cal, S.F.M. Resilience and ADHD: What is New. Res. Trends Chall. Med. Sci. 2021, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller-Thomson, E.; Ko, B.K.; Carrique, L.; MacNeil, A. Flourishing Despite Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): A Population Based Study of Mental Well-Being. Int. J. Appl. Posit. Psychol. 2022, 7, 227–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannotta, F.; Rydell, A.M. The prospective links between hyperactive/impulsive, inattentive, and oppositional-defiant behaviors in childhood and antisocial behavior in adolescence: The moderating influence of gender and the parent–child relationship quality. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2016, 47, 857–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, R.M.; Mikami, A.Y.; Normand, S. Social Resilience in Children with ADHD: Parent and Teacher Factors. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2021, 30, 839–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.C.; Yang, H.J.; Chen, V.C.H.; Lee, W.T.; Teng, M.J.; Lin, C.H.; Gossop, M. Meta-analysis of quality of life in children and adolescents with ADHD: By both parent proxy-report and child self-report using PedsQL™. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2016, 51, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesch, K.P. ‘shine bright like a diamond!’: Is research on high-functioning adhd at last entering the mainstream? J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2018, 59, 191–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfelder, E.N.; Kollins, S.H. Topical review: ADHD and health-risk behaviors: Toward prevention and health promotion. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2016, 41, 735–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollak, Y.; Shoham, R.; Dayan, H.; Gabrieli-Seri, O.; Berger, I. Symptoms of ADHD Predict Lower Adaptation to the COVID-19 Outbreak: Financial Decline, Low Adherence to Preventive Measures, Psychological Distress, and Illness-Related Negative Perceptions. J. Atten. Disor. 2022; Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retz, W.; Ginsberg, Y.; Turner, D.; Barra, S.; Retz-Junginger, P.; Larsson, H.; Asherson, P. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (adhd), antisociality and delinquent behavior over the lifespan. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 120, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, S.; Cocallis, K. ADHD and offending. J. Neural Transm. 2021, 128, 1009–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller-Thomson, E.; Lewis, D.A.; Agbeyaka, S. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Alcohol and Other Substance Use Disorders in Young Adulthood: Findings from a Canadian Nationally Representative Survey. Alcohol Alcohol. 2022, 57, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliva, F.; Mangiapane, C.; Nibbio, G.; Berchialla, P.; Colombi, N.; Vigna-Taglianti, F.D. Prevalence of cocaine use and cocaine use disorder among adult patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 143, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zulauf, C.A.; Sprich, S.E.; Safren, S.A.; Wilens, T.E. The complicated relationship between attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and substance use disorders. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2014, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.S.; Humphreys, K.L.; Flory, K.; Liu, R.; Glass, K. Prospective association of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and substance use and abuse/dependence: A meta-analytic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 31, 328–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charach, A.; Yeung, E.; Climans, T.; Lillie, E. Childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and future substance use disorders: Comparative meta-analyses. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2011, 50, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groenman, A.P.; Janssen, T.W.; Oosterlaan, J. Childhood psychiatric disorders as risk factor for subsequent substance abuse: A meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2017, 56, 556–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, O.; Chavanon, M.; Riechmann, E.; Christiansen, H. Emotional dysregulation is a primary symptom in adult Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 232, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Adler, L.; Barkley, R.; Biederman, J.; Conners, C.K.; Demler, O.; Faraone, S.V.; Greenhill, L.L.; Howes, M.J.; Secnik, K.; et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am. J. Psychiatry 2006, 163, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anker, E.; Bendiksen, B.; Heir, T. Comorbid psychiatric disorders in a clinical sample of adults with ADHD, and associations with education, work and social characteristics: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottosen, C.; Larsen, J.T.; Faraone, S.V.; Chen, Q.; Hartman, C.; Larsson, H.; Petersen, L.; Dalsgaard, S. Sex differences in comorbidity patterns of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2019, 58, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, R.T.; Kern, M.L.; Lyubomirsky, S. Health benefits: Meta-analytically determining the impact of well-being on objective health outcomes. Health Psychol. Rev. 2007, 1, 83–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Goldenberg, M.; Perry, R.; IsHak, W.W. The quality of life of adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A systematic review. Innov. Clin. Neurosci. 2012, 9, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pinho, T.D.; Manz, P.H.; DuPaul, G.J.; Anastopoulos, A.D.; Weyandt, L.L. Predictors and moderators of quality of life among college students with ADHD. J. Atten. Disord. 2019, 23, 1736–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stickley, A.; Koyanagi, A.; Takahashi, H.; Ruchkin, V.; Inoue, Y.; Yazawa, A.; Kamio, Y. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms and happiness among adults in the general population. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 265, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissenberger, S.; Ptacek, R.; Klicperova-Baker, M.; Erman, A.; Schonova, K.; Raboch, J.; Goetz, M. ADHD, lifestyles and comorbidities: A call for an holistic perspective–from medical to societal intervening factors. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuer, D.; von Wirth, E.; Mandler, J.; Schürmann, S.; Döpfner, M. Predicting delinquent behavior in young adults with a childhood diagnosis of ADHD: Results from the Cologne Adaptive Multimodal Treatment (CAMT) Study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 31, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapar, A.; Van den Bree, M.; Fowler, T.; Langley, K.; Whittinger, N. Predictors of antisocial behaviour in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2006, 15, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, B.H.; Vázquez, A.L.; Moses, J.O.; Cromer, K.D.; Morrow, A.S.; Villodas, M.T. Risk for substance use among adolescents at-risk for childhood victimization: The moderating role of ADHD. Child Abus. Negl. 2021, 114, 104977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dew, R.E.; Kollins, S.H.; Koenig, H.G. ADHD, religiosity, and psychiatric comorbidity in adolescence and adulthood. J. Atten. Disord. 2022, 26, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novis-Deutsch, N.; Dayan, H.; Pollak, Y.; Khoury-Kassabri, M. Religiosity as a moderator of ADHD-related antisocial behaviour and emotional distress among secular, religious and Ultra-Orthodox Jews in Israel. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2022, 68, 773–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagar, S. The Role of Protective Factors in Relation to Attentional Abilities in Emerging Adults. Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2021. Available online: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/8573 (accessed on 31 May 2022).

- Antonovsky, A. Unraveling the Mystery of Health: How People Manage Stress and Stay Well; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Antonovsky, A. Complexity, conflict, chaos, coherence, coercion and civility. Soc. Sci. Med. 1993, 37, 969–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langeland, E.; Vinje, H.F. Applying Salutogenesis in Mental Healthcare Settings. In The Handbook of Salutogenesis; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 433–439. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, M.; Lindström, B. Validity of Antonovsky’s sense of coherence scale: A systematic review. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2005, 59, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, M.; Lindström, B. Antonovsky’s sense of coherence scale and the relation with health: A systematic review. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2006, 60, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewin, A.; Mitchell, S.J.; Ronzio, C.R. Developmental differences in parenting behavior: Comparing adolescent, emerging adult, and adult mothers. Merrill-Palmer Q. 2013, 59, 23–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittelmark, M.B.; Bull, T.; Daniel, M.; Urke, H. Specific resistance resources in the salutogenic model of health. In The Handbook of Salutogenesis; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Winger, J.G.; Adams, R.N.; Mosher, C.E. Relations of meaning in life and sense of coherence to distress in cancer patients: A meta-analysis. Psycho-Oncology 2016, 25, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzdil, N.; Ceyhan, Ö.; Şimşek, N. The effect of salutogenesis-based care on the sense of coherence in peritoneal dialysis patients. J. Clin. Nurs. 2022, 31, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, M.; Lindström, B. Antonovsky’s sense of coherence scale and its relation with quality of life: A systematic review. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2007, 61, 938–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishi, K.; Suzuki, J.; Monma, T.; Asanuma, T.; Takeda, F. Psychosocial and criminological factors related to recidivism among Japanese criminals at offender rehabilitation facilities. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2018, 4, 1489458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristkari, T.; Sourander, A.; Ronning, J.; Helenius, H. Self-reported psychopathology, adaptive functioning and sense of coherence, and psychiatric diagnosis among young men. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2006, 41, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattila, M.-L.; Rautava, P.; Honkinen, P.-L.; Ojanlatva, A.; Jaakkola, S.; Aromaa, M.; Suominen, S.; Helenius, H.; Sillanpää, M. Sense of coherence and health behaviour in adolescence. Acta Paediatr. Int. J. Paediatr. 2011, 100, 1590–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, K.W.; Starrin, B.; Simonsson, B.; Leppert, J. Alcohol-related problems among adolescents and the role of a sense of coherence. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2007, 16, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Moya, I.; Jiménez-Iglesias, A.; Moreno, C. Sense of coherence and substance use in Spanish adolescents. Does the effect of SOC depend on patterns of substance use in their peer group? Adicciones 2013, 25, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dayan, H.; Khoury-Kassabri, M.; Pollak, Y. The link between ADHD symptoms and antisocial behavior: The moderating role of the protective factor sense of coherence. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Diagnostic Criteria for Research; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- del-Pino-Casado, R.; Espinosa-Medina, A.; López-Martínez, C.; Orgeta, V. Sense of coherence, burden and mental health in caregiving: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 242, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grevenstein, D.; Bluemke, M. Measurement invariance of the SOC-13 Sense of Coherence Scale across gender and age groups. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2022, 38, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, M.; Contu, P. The sense of coherence: Measurement Issues. In The Handbook of Salutogenesis; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 79–91. [Google Scholar]

- Carlén, K.; Suominen, S.; Lindmark, U.; Saarinen, M.M.; Aromaa, M.; Rautava, P.; Sillanpää, M. Sense of coherence predicts adolescent mental health. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 274, 1206–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, D.S.; Ageton, S.S. Reconciling race and class differences in self-reported and official estimates of delinquency. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1980, 45, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizur, Y.; Spivak, A.; Ofran, S.; Jacobs, S. A gender-moderated model of family relationships and adolescent adjustment. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2007, 36, 430–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, L.; O’Malley, P.M.; Bachman, J.G. National Survey Results on Drug Use from the Monitoring the Future Study, 1975–1994: College Students and Young Adults (No. 95); National Institute on Drug Abuse, US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health: Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Schiff, M.; Benbenishty, R.; Hamburger, R. Adolescents’ Exposure to Negative Life Events and Substance Use: RISK and Protective Factors—Comparison Between Adolescents who Were Born in the Former Soviet Union and Those who Were Born in Israel; Final Report; Israel Anti-Drug Authority (Hebrew): Jerusalem, Israel, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1997, 38, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R. Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2001, 40, 1337–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brann, P.; Lethbridge, M.J.; Mildred, H. The young adult Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) in routine clinical practice. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 264, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natvig, G.K.; Albrektsen, G.; Qvarnstrøm, U. Associations between psychosocial factors and happiness among school adolescents. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2003, 9, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zohar, A.H.; Konfortes, H. Diagnosing ADHD in Israeli adults: The psychometric properties of the adult ADHD Self Report Scale (ASRS) in Hebrew. Isr. J. Psychiatry Relat. Sci. 2010, 47, 308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Swanson, J.M.; Schuck, S.; Porter, M.M.; Carlson, C.; Hartman, C.A.; Sergeant, J.A.; Clevenger, W.; Wasdell, M.; McCleary, R.; Lakes, K.; et al. Categorical and Dimensional Definitions and Evaluations of Symptoms of ADHD: History of the SNAP and the SWAN Rating Scales. Int. J. Educ. Psychol. Assess. 2012, 10, 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel, Y. lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; Guilford publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idan, O.; Braun-Lewensohn, O.; Lindström, B.; Margalit, M. Salutogenesis: Sense of coherence in childhood and in families. In The Handbook of Salutogenesis; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 107–121. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez Álvarez, Ó.; Ruiz-Cantero, M.T.; Cassetti, V.; Cofino, R.; Álvarez-Dardet, C. Salutogenic interventions and health effects: A scoping review of the literature. Gac. Sanit. 2022, 35, 488–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. How to Use the Icf-A Practical Manual for Using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- de Schipper, E.; Mahdi, S.; Coghill, D.; De Vries, P.J.; Gau, S.S.F.; Granlund, M.; Holtmann, M.; Karande, S.; Levy, F.; Almodayfer, O.; et al. Towards an ICF core set for ADHD: A worldwide expert survey on ability and disability. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2015, 24, 1509–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loe, I.M.; Feldman, H.M. Academic and educational outcomes of children with ADHD. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2007, 32, 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edbom, T.; Malmberg, K.; Lichtenstein, P.; Granlund, M.; Larsson, J.O. High sense of coherence in adolescence is a protective factor in the longitudinal development of ADHD symptoms. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2010, 24, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudjonsson, G.H.; Gonzalez, R.A.; Young, S. The risk of making false confessions: The role of developmental disorders, conduct disorder, psychiatric symptoms, and compliance. J. Atten. Disord. 2021, 25, 715–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherkasova, M.V.; Roy, A.; Molina, B.S.; Scott, G.; Weiss, G.; Barkley, R.A.; Biederman, J.; Uchida, M.; Hinshaw, S.P.; Owens, E.B.; et al. Adult outcome as seen through controlled prospective follow-up studies of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder followed into adulthood. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 61, 378–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, L.; Gunby, P. Crime and mobility during the COVID-19 lockdown: A preliminary empirical exploration. N. Z. Econ. Pap. 2022, 56, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champ, R.E.; Adamou, M.; Tolchard, B. The impact of psychological theory on the treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in adults: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0261247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.F.; Egerod, I.; Bestle, M.H.; Christensen, D.F.; Elklit, A.; Hansen, R.L.; Knudsen, H.; Grode, L.B.; Overgaard, D. A recovery program to improve quality of life, sense of coherence and psychological health in icu survivors: A multicenter randomized controlled trial, the rapit study. Intensive Care Med. 2016, 42, 1733–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odajima, Y.; Kawaharada, M.; Wada, N. Development and validation of an educational program to enhance sense of coherence in patients with diabetes mellitus type 2. Nagoya J. Med. Sci. 2017, 79, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.K.; Chan, S.W.C.; Wang, W.; Vehviläinen-Julkunen, K. A salutogenic program to enhance sense of coherence and quality of life for older people in the community: A feasibility randomized controlled trial and process evaluation. Patient Educ. Couns. 2016, 99, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Category | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group | Adolescence, 15–17 | 133 | 27.4 |

| Emergent adulthood, 19–29 | 252 | 51.9 | |

| Adulthood, 30–50 | 101 | 20.8 | |

| Gender | Women | 217 | 45.1 |

| Men | 269 | 54.9 | |

| Country of Birth | Israel | 468 | 96.3 |

| Other | 18 | 3.7 | |

| Marital Status | Single | 234 | 48.2 |

| Married/In a relationship | 220 | 45.3 | |

| Divorced | 27 | 5.5 | |

| Other | 5 | 1.0 | |

| Religious Identity | Ultra-orthodox | 187 | 38.5 |

| Orthodox | 110 | 22.6 | |

| Traditional | 53 | 10.9 | |

| Non-religious | 122 | 25.1 | |

| Not defined | 14 | 2.9 | |

| Education | Elementary/High school | 162 | 33.3 |

| Up to 14 years | 177 | 36.5 | |

| Graduate | 147 | 30.2 | |

| Economic Status | Very low | 65 | 13.4 |

| Low | 138 | 28.3 | |

| Medium | 237 | 48.7 | |

| High | 40 | 8.2 | |

| Very high | 7 | 1.5 | |

| Employment Status | Not working | 196 | 40.4 |

| Part-time | 60 | 12.3 | |

| Full-time | 230 | 47.3 |

| Variable | M/N | SD/% | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Delinquency | 0.59 | 0.54 | |||||||

| 2. Drug Use | 1.08 | 1.36 | 0.31 ** | ||||||

| 3. Emotional Distress | 1.68 | 0.52 | 0.19 ** | −0.03 | |||||

| 4. Happiness | 1.69 | 0.82 | −0.22 ** | −0.03 | −0.45 ** | ||||

| 5. Gender (Women) | 217 | 45.1 | −0.12 ** | −0.19 ** | 0.27 ** | −0.2 ** | |||

| 6. Age Group (Adolescents) | 133 | 27.4 | −0.33 ** | 0.11 | −0.08 | 0.07 | 0.04 | ||

| 7. ADHD Symptoms | 1.84 | 0.68 | 0.26 ** | 0.04 | 0.36 ** | −0.27 ** | 0.11 * | −0.10 | |

| 8. Sense of Coherence | 4.37 | 1.15 | −0.41 ** | −0.07 | −0.61 ** | 0.51 ** | −0.14 ** | 0.22 ** | −0.38 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dayan, H.; Khoury-Kassabri, M.; Pollak, Y. Sense of Coherence Is Associated with Functional Impairment in Individuals Diagnosed with ADHD. Sci 2025, 7, 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7020060

Dayan H, Khoury-Kassabri M, Pollak Y. Sense of Coherence Is Associated with Functional Impairment in Individuals Diagnosed with ADHD. Sci. 2025; 7(2):60. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7020060

Chicago/Turabian StyleDayan, Haym, Mona Khoury-Kassabri, and Yehuda Pollak. 2025. "Sense of Coherence Is Associated with Functional Impairment in Individuals Diagnosed with ADHD" Sci 7, no. 2: 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7020060

APA StyleDayan, H., Khoury-Kassabri, M., & Pollak, Y. (2025). Sense of Coherence Is Associated with Functional Impairment in Individuals Diagnosed with ADHD. Sci, 7(2), 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7020060