The Role of Resilience as a Buffer for Burden and Psychological Distress in ADS Caregivers: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

- ASD caregivers will present high levels of burden—objective, measured as hours per day of care, and subjective, measured as perceived burden—psychological distress, and low levels of resilience.

- Caregivers with high levels of psychological distress will present a higher burden, both objective and subjective, and lower resilience than caregivers with low levels of psychological distress.

- The expected relationship pattern will show significant and positive relationships between psychological distress and objective and subjective burden, and significant but negative relationships between these three variables and resilience.

- A serial mediation of resilience and subjective burden will be full between objective burden and psychological distress.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Design and Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Psychological Distress

2.3.2. Subjective Burden

2.3.3. Resilience

2.3.4. Sociodemographic Variables and Objective Burden

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- APA, American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Elsabbagh, M.; Divan, G.; Koh, Y.J.; Kim, Y.S.; Kauchali, S.; Marcín, C.; Montiel-Nava, C.; Patel, V.; Paula, C.S.; Wang, C.; et al. Global prevalence of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Autism Res. 2012, 5, 160–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeidan, J.; Fombonne, E.; Scorah, J.; Ibrahim, A.; Durkin, M.S.; Saxena, S.; Yusuf, A.; Shih, A.; Elsabbagh, M. Global prevalence of autism: A systematic review update. Autism Res. 2022, 15, 778–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO, World Health Organization. Autism. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/autism-spectrum-disorders (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Loomes, R.; Hull, L.; Mandy, W.P. What is the male-to-female ratio in autism spectrum disorder? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2017, 56, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiller, R.M.; Young, R.L.; Weber, N. Sex differences in pre-diagnosis concerns for children later diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 2016, 20, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, C.; Elsabbagh, M.; Baird, G.; Veenstra-Vanderweele, J. Autism spectrum disorder. Lancet 2018, 392, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, M.; Donnelly, J. Factors mediating dysphoric moods and help seeking behaviour among Australian parents of children with autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2016, 46, 1941–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appah, J.; Senoo-Dogbey, V.E.; Armah, D.; Wuaku, D.A.; Ohene, L.A. A qualitative enquiry into the challenging roles of caregivers caring for children with autism spectrum disorders in Ghana. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2024, 76, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ten Hoopen, L.W.; de Nijs, P.F.A.; Duvekot, J.; Greaves-Lord, K.; Hillegers, M.H.J.; Brouwer, W.B.F.; Hakkaart-van Roijen, L. Children with an autism spectrum disorder and their caregivers: Capturing health-related and care-related quality of life. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2020, 50, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhower, A.S.; Baker, B.L.; Blacher, J. Preschool children with intellectual disability: Syndrome specificity, behaviour problems, and maternal well-being. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2005, 49, 657–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponsoda, J.M.; Díaz, A. Psychological distress in family caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease: Positive and negative aspects of caregiving. Global Health Econ. Sustain. 2024, 2, 3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekhet, A.K.; Johnson, N.L.; Zauszniewski, J.A. Resilience in family members of persons with autism spectrum disorder: A review of the literature. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2012, 33, 650–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, M.; Li, T.; Ma, W.; An, C.; Chen, Y.; Liu, S.; Kuang, W.; Yu, X.; et al. Prevalence and risk factors of anxiety, depression, and sleep problems among caregivers of people living with neurocognitive disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 590343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz, A.; Ponsoda, J.M.; Beleña, M.A. Optimism as a key to improving mental health in family caregivers of people living with Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Ment. Health 2020, 24, 1662–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponsoda, J.M.; Beleña, M.Á.; Díaz, A. Psychological distress in Alzheimer’s disease family caregivers: Gender differences and the moderated mediation of resilience. Healthcare 2023, 11, 3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padden, C.; James, J. Stress among parents of children with and without autism spectrum disorder: A comparison involving physiological indicators and parent self-reports. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 2017, 9, 567–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, A.; Suzuki, M.; Kato, M.; Suzuki, M.; Tanaka, S.; Shindo, T.; Taketani, K.; Akechi, T.; Furukawa, T.A. Emotional distress and its correlates among parents of children with pervasive developmental disorders. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2007, 61, 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N.; Frenn, M.; Feetham, S.; Simpson, P. Autism spectrum disorder: Parenting stress, family functioning and health-related quality of life. Fam. Syst. Health 2011, 29, 232–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, N.; Verhey, I.; Kuper, H. Depression and anxiety in parents of children with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, K.Q.P.; Loh, P.R. Mental health and coping in parents of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in Singapore: An examination of gender role in caring. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2019, 49, 2129–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, M.; Demir, Y.; Kırcalı, A.; İncedere, A. Caregiver burden in schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorders: A comparative study. Psychiatry Investig. 2021, 18, 1180–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baykal, S.; Karakurt, M.N.; Çakır, M.; Karabekiroğlu, K. An examination of the relations between symptom distributions in children diagnosed with autism and caregiver burden, anxiety and depression levels. Community Ment. Health J. 2019, 55, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingersoll, B.; Hambrick, D. The relationship between the broader autism phenotype, child severity, and stress and depression in parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2011, 5, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, C.C.; Smith, J.; Bent, C.A.; Chetcuti, L.; Sulek, R.; Uljarević, M.; Hudry, K. Differential predictors of well-being versus mental health among parents of pre-schoolers with autism. Autism 2021, 25, 1125–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorke, I.; White, P.; Weston, A.; Rafla, M.; Charman, T.; Simonoff, E. The association between emotional and behavioral problems in children with autism spectrum disorder and psychological distress in their parents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2018, 48, 3393–3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landon, J.; Shepherd, D.; Goedeke, S. Predictors of satisfaction with life in parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2018, 48, 1640–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, F.; Clyne, W.; Pearce, G.; Turner, A. Self-management support intervention for parents of children with developmental disorders: The role of gratitude and hope. J. Child. Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 980–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero, N.; McIntyre, L.L. Sibling adjustment and maternal well-being: An examination of families with and without a child with an autism spectrum disorder. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabil. 2010, 25, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, M.; McGrew, J.H. Caregiver burden after receiving a diagnosis of an autism spectrum disorder. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2009, 3, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qahtani, F.S. Experienced burden by caregivers of autistic children. Med. J. Cairo Univ. 2018, 86, 1523–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zarit, S.H.; Reever, K.E.; Bach-Peterson, J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: Correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist 1980, 20, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulud, Z.A.; McCarthy, G. Caregiver burden among caregivers of individuals with severe mental illness: Testing the moderation and mediation models of resilience. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2017, 31, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pruitt, M.M.; Rhoden, M.; Ekas, N.V. Relationship between the broad autism phenotype, social relationships and mental health for mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 2018, 22, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gere, J.; Goodman, B.J. Mechanics of Materials, 4th ed.; Cengage Learning: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. Maternal care and mental health. Bull. World Health Organ. 1951, 3, 355–533. [Google Scholar]

- Block, J.H.; Block, J. The Role of Ego-Control and Ego Resiliency in the Organization of Behavior; Collins, W.A., Ed.; Minnesota Symposium on Child Psychology; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1980; pp. 39–101. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, F. Strengthening Family Resilience, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Southwick, S.M.; Bonanno, G.A.; Masten, A.S.; Panter-Brick, C.; Yehuda, R. Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: Interdisciplinary perspectives. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2014, 5, 25338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Hartigh, R.J.R.; Hill, Y. Conceptualizing and measuring psychological resilience: What can we learn from physics? New Ideas Psychol. 2022, 66, 100934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, G.A.; Westphal, M.; Mancini, A.D. Resilience to loss and potential trauma. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 7, 511–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, Y.; Den Hartigh, R.J.R.; Meijer, R.R.; De Jonge, P.; Van Yperen, N.W. The temporal process of resilience. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 2018, 7, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J.R.T. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress. Anxiety 2003, 18, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiefer, A.W.; Silva, P.L.; Harrison, H.S.; Araújo, D. Antifragility in sport: Leveraging adversity to enhance performance. Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 2018, 7, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, Y.; Kiefer, A.W.; Silva, P.L.; Van Yperen, N.W.; Meijer, R.R.; Den Hartigh, R.J.R. Antifragility in climbing: Determining optimal stress loads for athletic performance training. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanouni, P.; Hood, G. Stress, coping, and resiliency among families of individuals with autism: A systematic review. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2021, 8, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowmida, M.S.; Novena, S.; Hothi, S.; Singh, V. Exploring the relationship between perceived social support, perceived stress, and resilience among caregivers of children with autism. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2023, 11, 437–441. [Google Scholar]

- Bekhet, A.K.; Johnson, N.L.; Zauszniewski, J.A. Effects on resilience of caregivers of persons with autism spectrum disorder: The role of positive cognitions. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2012, 18, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitsika, V.; Sharpley, C.; Bell, R. The buffering effect of resilience upon stress, anxiety and depression in parents of a child with an autism spectrum disorder. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 2013, 25, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanouni, P.; Eves, L. Resilience among parents and children with autism spectrum disorder. Ment. Illn. 2023, 2023, 2925530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, D.P.; Gater, R.; Sartorius, N.; Ustun, T.B.; Piccinelli, M.; Gureje, O. The validity of two versions of the GHQ in the WHO study of mental illness in general health care. Psychol. Med. 1997, 27, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifre, E.; Salanova, M. Validación factorial de “General Health Questionnaire” (GHQ-12) mediante un análisis factorial confirmatorio [Factor validation of “General Health Questionnaire” (GHQ-12) through a confirmatory factor analysis]. J. Health Psychol. 2000, 12, 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Lundin, A.; Ahs, J.; Asbring, N.; Kosidou, K.; Dal, H.; Tinghog, P.; Saboonchi, F.; Dalman, C. Discriminant validity of the 12-item version of the general health questionnaire in a Swedish case-control study. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2016, 71, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Carrasco, M.; Otermin, P.; Pérez-Camo, V.; Pujol, J.; Agüera, L.; Martín, M.J.; Gobarrt, A.L.; Pons, S.; Balana, M. EDUCA study: Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Zarit Caregiver Burden Scale. Aging Ment. Health 2010, 14, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, M.; Fernandez-Lansac, V.; Soberon, C. Spanish version of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) for chronic stress situations. Behav. Psychol. 2014, 22, 219–238. [Google Scholar]

- Okuyama, J.; Funakoshi, S.; Tomita, H.; Yamaguchi, T.; Matsuoka, H. Longitudinal characteristics of resilience among adolescents: A high school student cohort study to assess the psychological impact of the Great East Japan Earthquake. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2018, 72, 821–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart, M.; Sörensen, S. Gender differences in caregiver stressors, social resources, and health: An updated meta-analysis. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2006, 61, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonnell, E.; Ryan, A.A. The experience of sons caring for a parent with dementia. Dementia 2014, 13, 788–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penning, M.J.; Wu, Z. Caregiver stress and mental health: Impact of caregiving relationship and gender. Gerontologist 2016, 56, 1102–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revenson, T.A.; Konstadina, G.; Aleksandra, L.; Morrison, V.; Panagopoulou, E.; Vilchinsky, N.; Hagedoorn, M. Gender and Caregiving: The Costs of Caregiving for Women. In Caregiving in the Illness Context; Revenson, T.A., Griva, K., Luszczynska, A., Morrison, V., Panagopoulou, E., Vilchinsky, N., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2016; pp. 49–63. [Google Scholar]

- Alnazly, E.K.; Abojedi, A. Psychological distress and perceived burden in caregivers os person with autism spectrum disorder. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2019, 55, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalb, L.G.; Badillo-Goicoechea, E.; Holingue, C.; Riehm, K.E.; Thrul, J.; Stuart, E.A.; Smail, E.J.; Law, K.; White-Lehman, C.; Fallin, D. Psychological distress among caregivers raising a child with autism spectrum disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic. Autism Res. 2021, 14, 2183–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safe, A.; Joosten, A.; Molineux, M. The experiences of mothers of children with autism: Managing multiple roles. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2012, 37, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Feng, Y.; Qu, F.; Luo, Y.; Chen, B.; Chen, M.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, L. Posttraumatic growth among parents of children with autism spectrum disorder in China and its relationship to family function and mental resilience: A cross-sectional study. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2021, 57, e59–e67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoulpoor, S.; Salari, N.; Shiani, A.; Khaledi-Paveh, B.; Mohammadi, M. Determining the relationship between over-care burden and coping styles, and resilience in mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2023, 49, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, K.N.; Rossetti, K.G.; Zlomke, K. Community support, family resilience and mental health among caregivers of youth with autism spectrum disorder. Child Care Health Dev. 2023, 49, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jadiri, A.; Tybor, D.J.; Mulé, C.; Sakai, C. Factors associated with resilience in families of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2021, 42, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakurian, D. Resilience in family caregivers of adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder: An Integrative Review of the literature. Innov. Aging 2021, 17 (Suppl. S1), 817–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Men | 54 | 21.6 |

| Women | 196 | 78.4 | |

| Education level | Primary | 33 | 13.2 |

| Secondary | 90 | 36.0 | |

| University | 127 | 50.8 | |

| Marital status/cohabiting | Married/with partner | 219 | 87.6 |

| Single/widow/separated | 31 | 12.4 | |

| Relation with the care recipient | Parents | 240 | 96.0 |

| Other | 10 | 4.0 |

| N | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hours per day caring (Objective burden) | <5 h | 16 | 6.4 |

| 5–10 h | 71 | 28.0 | |

| 11–15 h | 57 | 22.8 | |

| >15 h | 106 | 42.4 | |

| Perceived burden (Subjective burden) (M/SD) | (54.56/12.25) | ||

| Low burden | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Mild | 40 | 16.0 | |

| Moderate | 125 | 50.0 | |

| Severe | 85 | 34.0 | |

| Psychological distress (M/SD) | (14.34/6.13) | ||

| High | 124 | 49.6 | |

| Low | 126 | 50.4 | |

| Resilience (M/SD) | (65.27/11.82) | ||

| High | 142 | 56.8 | |

| Low | 108 | 43.2 |

| Variables | Psychological Distress | N | M | DT | t | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver age | High | 124 | 42.59 | 6.92 | ||

| Low | 126 | 42.60 | 6.61 | −0.01 | --- | |

| Care recipient age | High | 124 | 8.28 | 5.26 | ||

| Low | 126 | 8.64 | 5.32 | −0.54 | --- | |

| Hours/day caring | High | 124 | 3.14 | 0.91 | ||

| Low | 126 | 2.89 | 1.05 | 2.01 * | 0.26 | |

| Perceived burden | High | 124 | 61.91 | 12.79 | ||

| Low | 126 | 47.33 | 11.70 | 9.40 *** | 1.19 | |

| Resilience | High | 124 | 59.22 | 10.90 | ||

| Low | 126 | 71.30 | 9.36 | −9.41 *** | 1.19 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Caregiver age | 1 | |||||

| 2. Care recipient age | 0.64 *** | 1 | ||||

| 3. Hours/day caring | −0.14 * | −0.11 | 1 | |||

| 4. Perceived burden | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.26 *** | 1 | ||

| 5. Psychological distress | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.19 ** | 0.63 *** | 1 | |

| 6. Resilience | −0.06 | −0.10 | −0.15 * | −0.51 *** | −0.60 *** | 1 |

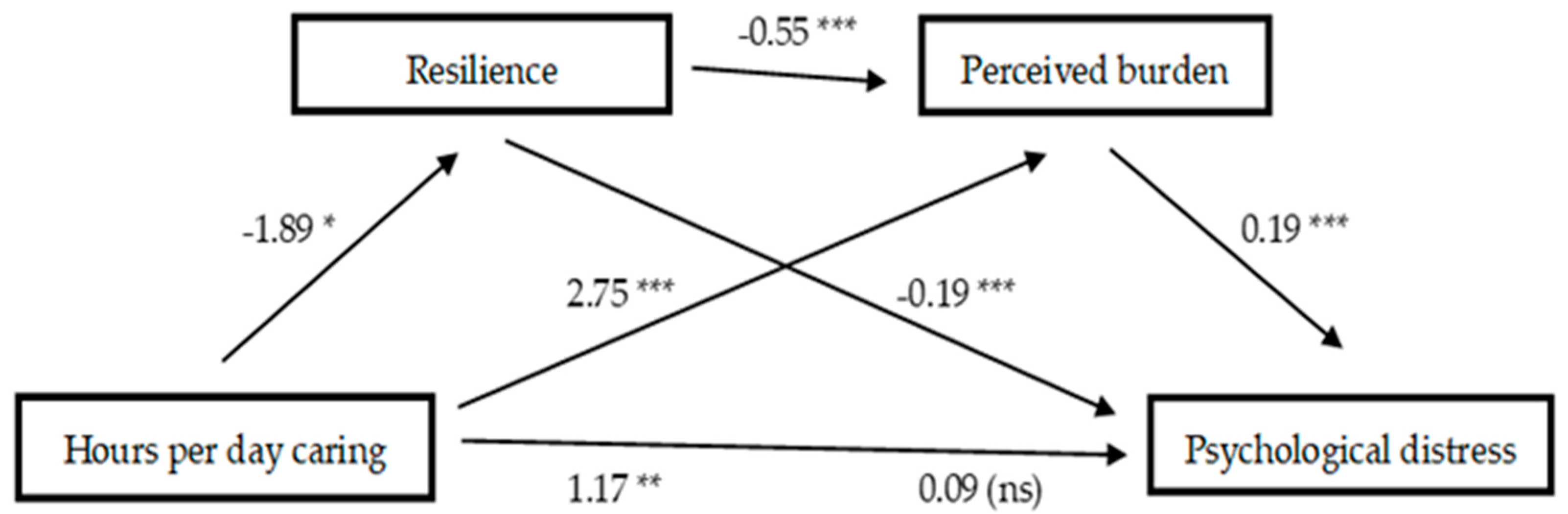

| Bootstrapping 95% Confidence Interval | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effects | Point Estimate | SE | Lower | Upper |

| 1. Hours/day caring—Resilience—Psychological Distress | 0.35 | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.69 |

| 2. Hours/day caring—Resilience—Perceived Burden—Psychological Distress | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.42 |

| 3. Hours/day caring—Perceived Burden—Psychological distress | 0.52 | 0.16 | 0.24 | 0.86 |

| Contrasts | ||||

| Model 1 versus Model 2 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0.43 |

| Model 1 versus Model 3 | −0.17 | 0.23 | −0.65 | 0.30 |

| Model 2 versus Model 3 | −0.33 | 0.20 | −0.72 | 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Herrero, R.; Díaz, A. The Role of Resilience as a Buffer for Burden and Psychological Distress in ADS Caregivers: A Cross-Sectional Study. Sci 2025, 7, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7020038

Herrero R, Díaz A. The Role of Resilience as a Buffer for Burden and Psychological Distress in ADS Caregivers: A Cross-Sectional Study. Sci. 2025; 7(2):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7020038

Chicago/Turabian StyleHerrero, Raquel, and Amelia Díaz. 2025. "The Role of Resilience as a Buffer for Burden and Psychological Distress in ADS Caregivers: A Cross-Sectional Study" Sci 7, no. 2: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7020038

APA StyleHerrero, R., & Díaz, A. (2025). The Role of Resilience as a Buffer for Burden and Psychological Distress in ADS Caregivers: A Cross-Sectional Study. Sci, 7(2), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7020038