Patterns of Learning: A Systemic Analysis of Emergency Response Operations in the North Sea through the Lens of Resilience Engineering

Abstract

1. Introduction

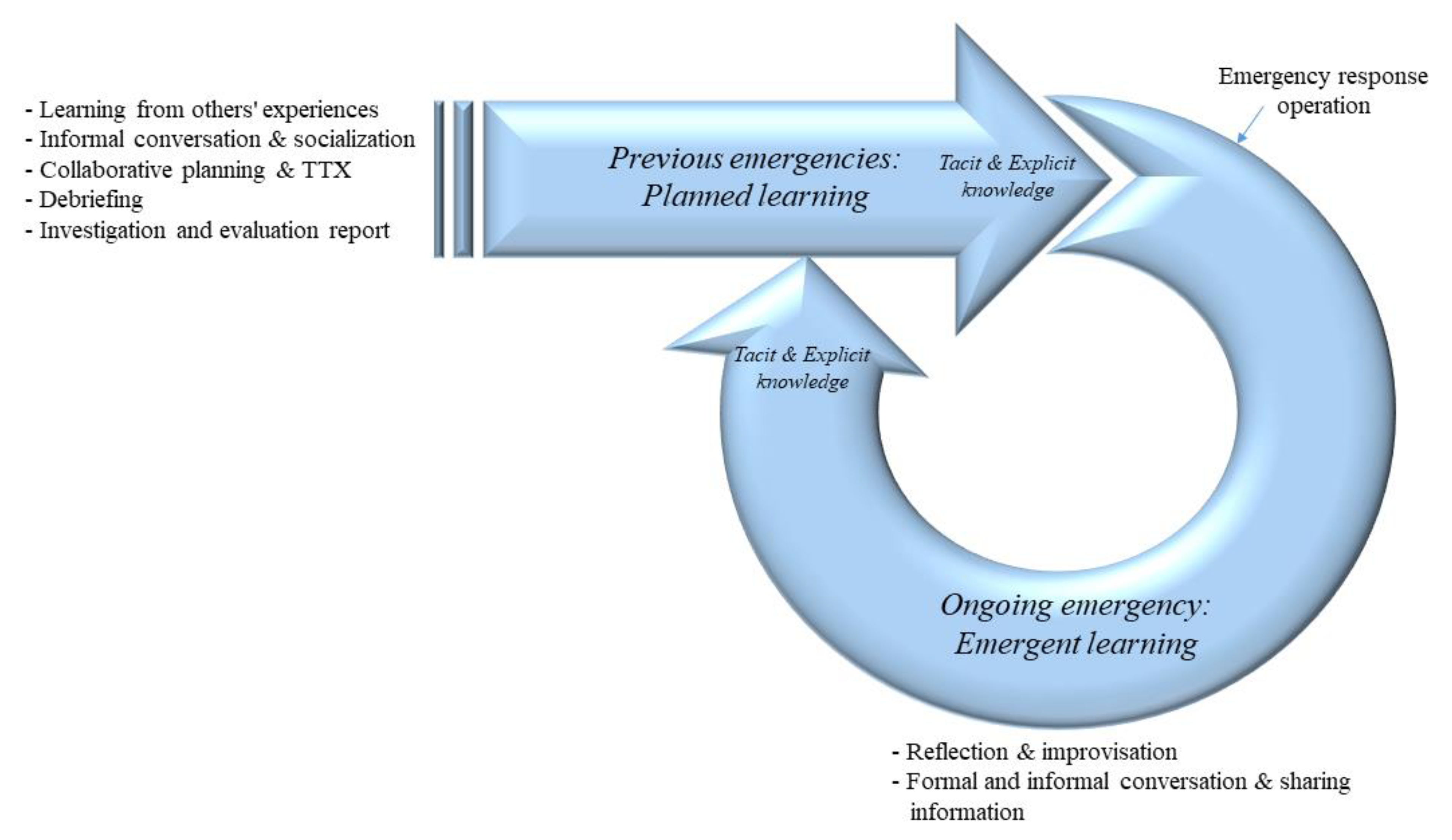

2. Theoretical Background: Patterns of Learning and Learning Barriers

3. Methodology

3.1. Three Cases of COVID-19 Outbreaks on the West Phoenix

3.1.1. Case 1: August 2020

3.1.2. Case 2: October 2020

3.1.3. Case 3: December 2020

3.2. Cognitive Task Analysis (CTA)

3.2.1. Knowledge Elicitation

3.2.2. Ethnographic Research

3.2.3. Semi-Structured Interviews

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Findings

4.1. Supporting Coordination and Synchronization of Distributed Operations

“We had regular updates every morning, and we had a system where we got approved the messages that were going out remotely”.

“Kristiansund municipality welcomed our ER team. It was a good and close collaboration with them”.

“Mutual trust and good relations developed in advance had a good effect on samhandling”.

“Conducting regular online meetings provided us a common situational picture”.

“There were no guidelines for who should notify the airline”.

“Roles and responsibilities within the COVID-19 handling were unclear. There was disagreement related to whether this was an emergency incident or not”.

“The situation was involved with a high level of uncertainty”.

“The absence of relevant plans led to different handling of the incidents. The strategic management’s perception of the situation was decisive for the approach”.

“The absence of relevant plans led to different handling of the incidents. The strategic management’s perception of the situation was decisive for the approach”.

4.2. Managing Adaptive Capacity

“We didn’t sit down together to discuss how we should handle, organise and use the resources in such an imagined situation”.

“The absence of relevant plans led to different handling of the incidents. The strategic management’s perception of the situation was decisive for the approach”.

“Routines must be developed, both on how to communicate internally and to the press in ambiguous situations, make a balance between reaching stakeholders’ factual information while navigating uncertainty, is a challenging task”.

“It was different expectation and practice in dealing with outbreaks. The rig had its procedures and routines for internal communication, Neptune had its own- lack of control and interoperability caused uncertainty”.

“Informal aspect of communication was important. Plans and manuals can never describe all possible eventualities”.

4.3. Developing and Revising Procedures and Checklists

“We had plans and procedures, but these were insufficient to deal with of COVID-19. So, we had to improvise”.

5. Discussion

5.1. Emergent Learning: Reflection and Improvisation

5.2. Planned Learning

5.2.1. Debriefing

5.2.2. Collaborative Planning and Tabletop Exercises

5.2.3. Informal Conversation

5.2.4. Learning from Others’ Experiences

5.3. Learning Barriers

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Woods, D. The theory of graceful extensibility: Basic rules that govern adaptive systems. Former. Environ. 2018, 38, 433–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boin, A.; Lodgeb, M.; Luesink, M. Learning from the COVID-19 crisis: An initial analysis of national responses. Policy Des. Pract. 2020, 3, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boin, A.; Ekengren, M.; Rhinard, M. Hiding in Plain Sight: Conceptualizing the Creeping Crisis. Risk Hazards Crisis Public Policy 2020, 11, 116–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donovan, S.-L.; Salmon, P.M.; Horberry, T.; Lenné, M.G. Ending on a positive: Examining the role of safety leadership decisions, behaviours and actions in a safety critical situation. Appl. Ergon. 2018, 66, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boin, A.; Bynander, F. Explaining success and failure in crisis coordination. Geogr. Ann. Ser. A Phys. Geogr. 2015, 97, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, D.; Macpherson, A. Policy and Practice: Recursive Learning From Crisis. Group Organ. Manag. 2010, 35, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veil, S. Mindful learning in crisis management. J. Bus. Commun. 2011, 48, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boin, A.; Hart, P.; Stern, E.; Sundelius, B. The Politics of Crisis Management: Public Lleadership Under Pressure, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mosier, K.; Fischer, U.; Hoffman, R.R.; Klein, G. Expert Professional Judgments and “Naturalistic Decision Making”. In The Cambridge Handbook of Expertise and Expert Performance; Ericsson, K.A., Hoffman, R.R., Kozbelt, A., Williams, A.M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 453–475. [Google Scholar]

- Cleeren, K.; Dekimpe, M.; van Heerde, H.J. Marketing research on product-harm crises: A review, managerial implications, and an agenda for future research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 593–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steen, R.; Rønningsbakk, B. Emergent learning during crisis: A case study of the arctic circle border crossing at Storskog in Norway. Risk Hazards Crisis Public Policy 2021, 12, 158–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslen, S.; Hayes, J. “This is How we Debate”: Engineers’ Use of Stories to Reason through Disaster Causation. Qual. Sociol. 2020, 43, 191–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sydnes, A.K.; Sydnes, M.; Hamnevoll, H. Learning from crisis: The 2015 and 2017 avalanches in Longyearbyen. Saf. Sci. 2021, 134, 105045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deverell, E. Learning and Crisis. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics; Thompson, W.R., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, N.; Alison, L. Decision inertia in critical incidents. Eur. Psychol. 2018, 24, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, G.A.; Hoffman, R.R. Seeing the invisible: Perceptual-cognitive aspects of expertise. In Cognitive Science Foundations of Instruction; Rabinowitz, M., Ed.; Eribaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1992; pp. 203–226. [Google Scholar]

- Hood, C. Hat happens when transparency meets blame-avoidance? Public Manag. Rev. 2007, 9, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbusera, L.; Cardarilli, M.; Giannopoulos, G. The ERNCIP survey on COVID-19: Emergency & Business Continuity for fostering resilience in critical infrastructures. Saf. Sci. 2021, 139, 105161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, S.; Ou, J.-C.; Ma, H.-P. Measurement of resilience potentials in emergency departments: Applications of a tailored resilience assessment grid. Saf. Sci. 2020, 121, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patriarca, R.; Falegnami, A.; Costantino, F.; Bilotta, F. Resilience engineering for socio-technical risk analysis: Application in neuro-surgery. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2018, 180, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, C.; Sasangohar, F.; Rao, A.H.; Larsen, E.P.; Neville, T. Resilient performance of emergency department: Patterns, models and strategies. Saf. Sci. 2019, 120, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, D. Resilience: The Governance of Complexity; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Mendonça, D. Measures of resilient performance. In Resilience Engineering Perspectives: Remaining Sensitive to the Possibility of Failure; Hollnagel, E., Nemeth, C.P., Dekker, S., Eds.; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK, 2008; Volume 1, pp. 29–47. [Google Scholar]

- DRMG. Darwin Resilience Management Guidelines. 2018, p. 148. Available online: https://h2020darwin.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/DRMG_Book.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Santos-Neto, J.B.S.d.; Costa, A.P.C.S. Enterprise maturity models: A systematic literature review. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 2019, 13, 719–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Enterprise Risk Management Maturity Model. In Tax Administration Maturity Model Series; Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development OECD: Paris, France, 2021; p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Alderson, D.L.; Darken, R.P.; Eisenberg, D.A.; Seager, T.P. Surprise is inevitable: How do we train and prepare to make our critical infrastructure more resilient? Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 72, 102800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedrini, V.; Mancini, M.; Rosi, L.; Mandarino, G.; Giorgi, S.; Herrera, I.; Branlat, M.; Pettersson, J.; C.-O., J.; Save, L.; et al. Improving resilience management for critical infrastructures—strategies and practices across air traffic management and healthcare. In Safety and Reliability–Safe Societies in a Changing World; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 1319–1327. [Google Scholar]

- Hermelin, J.; Bengtsson, K.; Woltjer, R.; Trnka, J.; Thorstensson, M.; Pettersson, J.; Prytz, E.; Jonson, C.-O. Operationalising resilience for disaster medicine practitioners: Capability development through training, simulation and reflection. Cogn. Technol. Work. 2020, 22, 667–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersson, J.; Jonson, C.O.; Berggren, P.; Hermelin, J.; Trnka, J.; Woltjer, R.; Prytz, E. Connecting resilience concepts to operational behaviour: A disaster exercise case study. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2022, 30, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wears, R.L.; Webb, L.K. Fundamental on situational surprise: A case study with implications for resilience. In Resilience Engineering in Practice: Becoming Resilient; Nemeth, P.C., Hollnagel, E., Eds.; CRC Press: Farnham, UK, 2014; Volume 2, pp. 33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Popper, M.; Lipshitz, R. Organizational Learning Mechanisms. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 1998, 34, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, C. Double-Loop Learning, Teaching, and Research. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2002, 1, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosey, P.; Visser, M.; Saunders, M.N. The origins and conceptualizations of ‘triple-loop’ learning: A critical review. Manag. Learn. 2012, 43, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Hwang, C.; Moon, M.J. Policy learning and crisis policy-making: Quadruple-loop learning and COVID-19 responses in South Korea. Policy Soc. 2020, 39, 363–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiro, T.J.; Torgersen, G.E. Samhandling Under Risk: Applying Concurrent Learning to Prepare for and Meet the Unforeseen. In Interaction: ‘Samhandling’ Under Risk: A Step Ahead of the Unforeseen; Torgersen, G.E., Ed.; Cappelen Damm Akademisk/NOASP Nordic Open Access Scholarly Publishing: Oslo, Sweden, 2018; pp. 252–265. [Google Scholar]

- Moskaliuk, J.; Bokhorst, F.; Cress, U. Learning from others’ experiences: How patterns foster interpersonal transfer of knowledge-in-use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 55, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryle, G. The Concept of Mind; Hutchinson: London, UK, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, G. Streetlights and Shadows: Searching for the Keys to Adaptive Decision Making; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Patriarca, R.; Falegnami, A.; Costantino, F.; Di Gravio, G.; De Nicola, A.; Villani, M.L. WAx: An integrated conceptual framework for the analysis of cyber-socio-technical systems. Saf. Sci. 2021, 136, 105142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torgersen, G.E.; Steiro, T.J. Defining the Term Samhandling. In Interaction: ‘Samhandling’ Under Risk. A Step Ahead of the Unforesee; Torgersen, G.E., Ed.; Cappelen Damm Akademisk/NOASP (Nordic Open Access Scholarly Publishing): Oslo, Norway, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Steen, R.; Haakonsen, G.; Patriarca, R. “Samhandling”: On the nuances of resilience through case study research in emergency response operations. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2022, 30, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keithly, D.M.; Ferris, S.P. “Auftragstaktik,” or Directive Control, in Joint and Combined Operations. Parameters 1999, 29, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offerdal, A.; Jacobsen, J.O. Auftragstaktik in the Norwegian armed forces. Def. Anal. 1993, 9, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonacopoulou, E.P.; Moldjord, C.; Steiro, T.J.; Stokkeland, C. The New Learning Organisation: PART II—Lessons from the Royal Norwegian Air Force Academy. Learn. Organ. 2019, 27, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, M.d.G.; Clegg, S.; Pina e Cunha, M.; Giustiniano, L.; Rego, A. Improvising Prescription: Evidence from the Emergency Room. Brit. J. Manag. 2016, 27, 406–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiro, T.J.; Vennatrø, R.; Bergh, J.; Torgersen, G.-E. On the Dynamics of Structure, Power, and Interaction: A Case Study from a Software Developing Company. Int. J. Manag. Knowl. Learn. 2022, 11, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengnick-Hall, C.A.; Beck, T.E. Resilience capacity and strategic agility: Prerequisites for thriving in a dynamic environment. In Resilience Engineering Perspectives; Hollnagel, E., Nemeth, C.P., Dekker, S., Eds.; Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 2009; Volume 2, pp. 39–69. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha, M.P.e.; Gomes, E.; Mellahi, K.; Miner, A.S.; Rego, A. Strategic agility through improvisational capabilities: Implications for a paradox-sensitive HRM. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2020, 30, 100695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woltjer, R.; Johansson, B.J.E.; Oskarsson, P.-A.; Svenmarck, P.; Kirwan, B. Air Transport System Agility: The Agile Response Capability (ARC) Methodology for Crisis Preparedness. Infrastructures 2022, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollnagel, E. The four cornerstones of resilience engineering. In Resilience Engineering Perspectives: Preparation and Restoration; Hollnagel, E., Nemeth, C.P., Dekker, S., Eds.; Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 2009; Volume 2, pp. 112–130. [Google Scholar]

- Kayes, D.C. Revisiting the Universal Dilemma of Learning in Policy, Government, and Organizational Culture. In Organizational Resilience: How Learning Sustains Organizations in Crisis, Disaster, and Breakdown; Kayes, D.C., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provan, D.J.; Woods, D.D.; Dekker, S.W.A.; Rae, A.J. Safety II professionals: How resilience engineering can transform safety practice. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2020, 195, 106740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ose, G.O.; Steiro, T.J. An Analytical Framework for Resilience Exemplified With a Real-Time Operational Center. ASCE-ASME J. Risk Uncertain. Eng. Syst. Part B. Mech. Eng. 2020, 6, 011004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, K.E. Puzzles in Organizational Learning: An Exercise in Disciplined Imagination. Br. J. Manag. 2002, 13, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klev, R. Participative Transformation: Learning and Development in Practising Change; Gower: Farnham, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Duffey, R.B.; Skjerve, A.B. Risk trends, indicators and learning rates: A new case study of North sea oil and gas. In Safety, Reliability and Risk Analyses: Theory, Methods and Applications, Proceedings of the 17th European Safety and Reliability Conference (ESREL 2008), Valencia, Spain, 7-10 September 2015; Martorell, S., Soares, C.G., Barnett, J., Eds.; CRC Press, Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 2008; pp. 941–949. [Google Scholar]

- Ansell, C.; Boin, A. Taming Deep Uncertainty: The Potential of Pragmatist Principles for Understanding and Improving Strategic Crisis Management. Adm. Soc. 2017, 51, 1079–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broekema, W.; Porth, J.; Steen, T.; Torenvlied, R. Public leaders’ organizational learning orientations in the wake of a crisis and the role of public service motivation. Saf. Sci. 2019, 113, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, K.; Steen, R. Total Defence Resilience: Viable or Not During COVID-19? A Comparative Study of Norway and the UK. Risks Hazards Crisis Public Policy 2020, 12, 73–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boin, A.; Bynander, F.; Stern, E.; Hart, P. Leading in a Crisis: Organisational Resilience in Mega-Crises. ANZSOG: Victoria, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, H.A. Rational Decision Making in Business Organizations. Am. Econ. Rev. 1979, 69, 493–513. [Google Scholar]

- Weick, K.E. The Collapse of Sensemaking in Organizations: The Mann Gulch Disaster. Adm. Sci. Q. 1993, 38, 628–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renå, H.; Christensen, J. Learning from crisis: The role of enquiry commissions. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2019, 28, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boin, A.; T Hart, P. Organising for Effective Emergency Management: Lessons from Research 1. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2010, 69, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, C.; Schön, D.A. Organizational Learning: A Theory of Action Perspective; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, 1978; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Staw, B.M.; Sandelands, L.E.; Dutton, J.E. Threat Rigidity Effects in Organizational Behavior: A Multilevel Analysis. Adm. Sci. Q. 1981, 26, 501–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, E. Crisis and Learning: A Conceptual Balance Sheet. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 1997, 5, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, K.E.D. Christopher Kayes: Organizational Resilience: How Learning Sustains Organizations in Crisis, Disaster, and Breakdowns. Adm. Sci. Q. 2016, 61, NP8–NP10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Militello, L.G.; Hutton, R.J.B. Applied cognitive task analysis (ACTA): A practitioner’s toolkit for understanding cognitive task demands. Ergonomics 1998, 41, 1618–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crandall, B.W.; Hoffman, R.R. Cognitive Task Analysis. In The Oxford Handbook of Cognitive Engineering; Lee, J.D., Kirlik, A., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 229–239. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, C.; Rossman, G. Designing Qualitative Research (3rd ed.), 6th ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, S.; Greenwood, M.; Prior, S.; Shearer, T.; Walkem, K.; Young, S.; Walker, K. Purposive sampling: Complex or simple? Research case examples. J. Res. Nurs. 2020, 25, 652–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantelmi, R.; Steen, R.; Di Gravio, G.; Patriarca, R. Resilience in emergency management: Learning from COVID-19 in oil and gas platforms. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 76, 103026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rake, E.L.; Bøhm, M. Incident Commander as the leader on-scene Research methods, tasks and roles. In Proceedings of the Nordic Fire & Safety Days, Trondheim, Norway, 6–7 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schraagen, J.M.C.; van de Ven, J.G.M. Human factors aspects of ICT for crisis management. Cogn. Technol. Work. 2011, 13, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, J. Outlines of a hybrid model of the process plant operator. In Monitoring Behavior and Supervisory Control; Johannsen, G., Sheridan, T.B., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1976; pp. 371–383. [Google Scholar]

- Levinthal, D.; Rerup, C. Crossing an Apparent Chasm: Bridging Mindful and Less-Mindful Perspectives on Organizational Learning. Organ. Sci. 2006, 17, 502–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, D.; Smith, D.; McGuinness, M. Exploring the Failure To Learn: Crises and the Barriers to Learning. Rev. Bus. 2000, 21, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Helsloot, I.; Groenendaal, J. It’s meaning making, stupid! Success of public leadership during flash crises. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2017, 25, 350–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayes, C.D.; Yoon, J. The breakdown and rebuilding of learning during organizational crisis, disaster, and failure. Organ. Dyn. 2016, 45, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiro, T.J.; Torgersen, G.E. The terms of interaction and concurrent learning in the definition of integrated operations. In Integrated Operations in the Oil and Gas Industry: Sustainability and Capability Development; Rosendahl, T., Hepsø, V., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2013; pp. 328–340. [Google Scholar]

| Categories | Barrier |

|---|---|

| Power and politics |

|

| Sociopsychological barriers |

|

| Information processing |

|

| DRMG Theme | Capability Card | Claims |

|---|---|---|

| Supporting the coordination and synchronization of distributed operations | CC1: Common ground | The OFFB had a contingency plan that was relevant and comprehensive for dealing with a COVID-19-related scenario. |

| CC2: Establishing networks | The OFFB had established good and well-known strategies, networks, and plans for handling COVID-19 outbreaks. | |

| Managing adaptive capacity | CC3: Enhancing the capacity to adapt | The OFFB had established a high-risk awareness associated with COVID-19 scenarios and a well-developed organizational and management culture that strengthened the company’s ability to handle COVID-19-related events. |

| CC4: Establishing conditions for adapting plans | The OFFB has good systems for assessing learning effects at all levels of the organization (individual, group, and organization). If necessary, the assessment of learning effects leads to adapting plans and new learning measures. We found that one or more problems could not be solved by following established procedures and plans; therefore, we had to improvise. These experiences have led to learning in the organization. | |

| CC5: Managing available resources | The OFFB has developed its contingency plans for managing available resources in handling a COVID-19-related scenario, based on legal requirements, industry standards, risk assessments, the involvement of professionals, and experiences. | |

| Developing and revising procedures and checklists | CC6: Systematic management of policies | The OFFB has a well-established system for learning what went well and what can be improved after the handling of the COVID-19 incident. The OFFB has established detailed criteria for how findings from COVID-19 events are to be investigated and analyzed. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Steen, R.; Haakonsen, G.; Steiro, T.J. Patterns of Learning: A Systemic Analysis of Emergency Response Operations in the North Sea through the Lens of Resilience Engineering. Infrastructures 2023, 8, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures8020016

Steen R, Haakonsen G, Steiro TJ. Patterns of Learning: A Systemic Analysis of Emergency Response Operations in the North Sea through the Lens of Resilience Engineering. Infrastructures. 2023; 8(2):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures8020016

Chicago/Turabian StyleSteen, Riana, Geir Haakonsen, and Trygve Jakobsen Steiro. 2023. "Patterns of Learning: A Systemic Analysis of Emergency Response Operations in the North Sea through the Lens of Resilience Engineering" Infrastructures 8, no. 2: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures8020016

APA StyleSteen, R., Haakonsen, G., & Steiro, T. J. (2023). Patterns of Learning: A Systemic Analysis of Emergency Response Operations in the North Sea through the Lens of Resilience Engineering. Infrastructures, 8(2), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures8020016