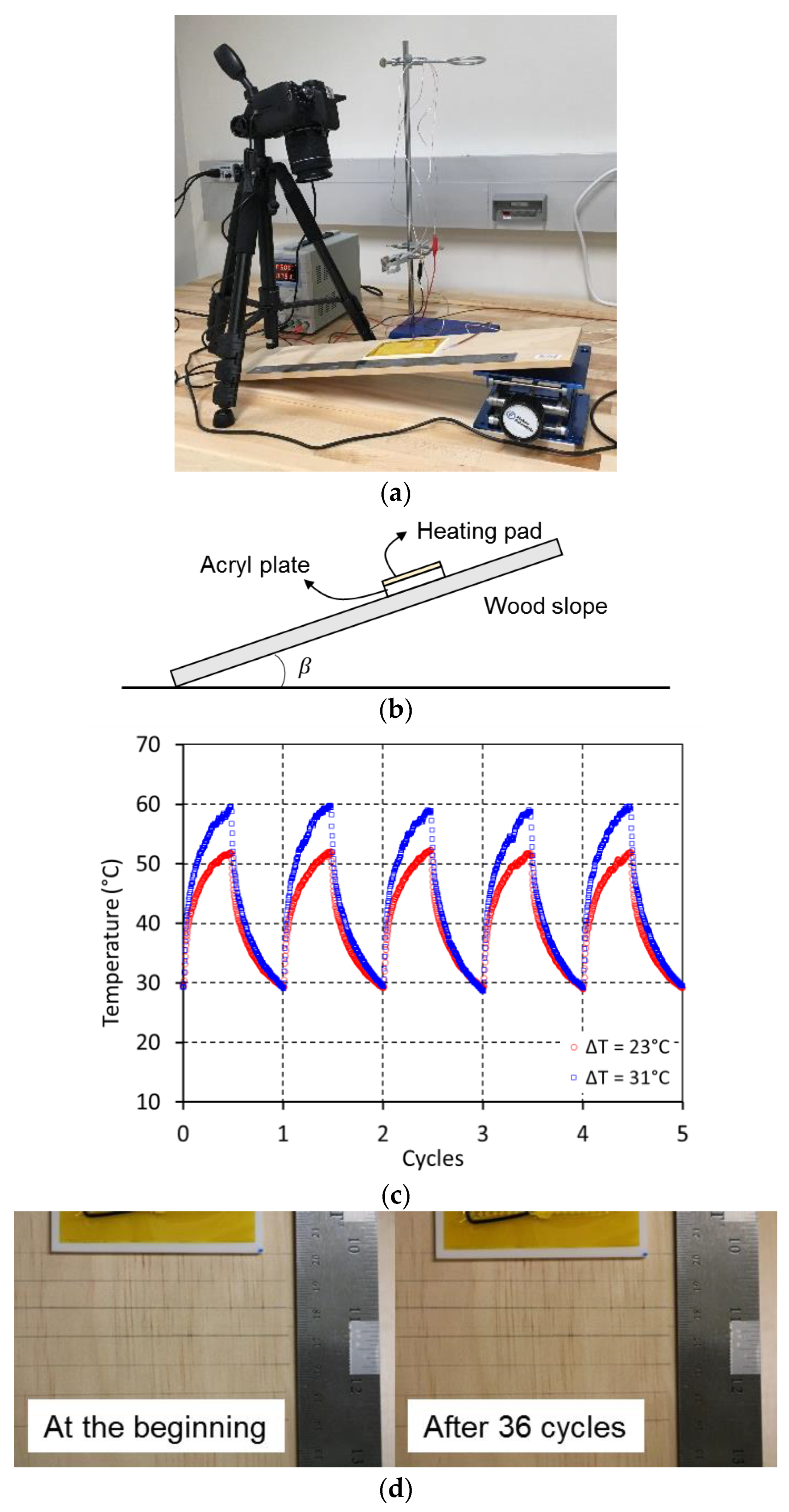

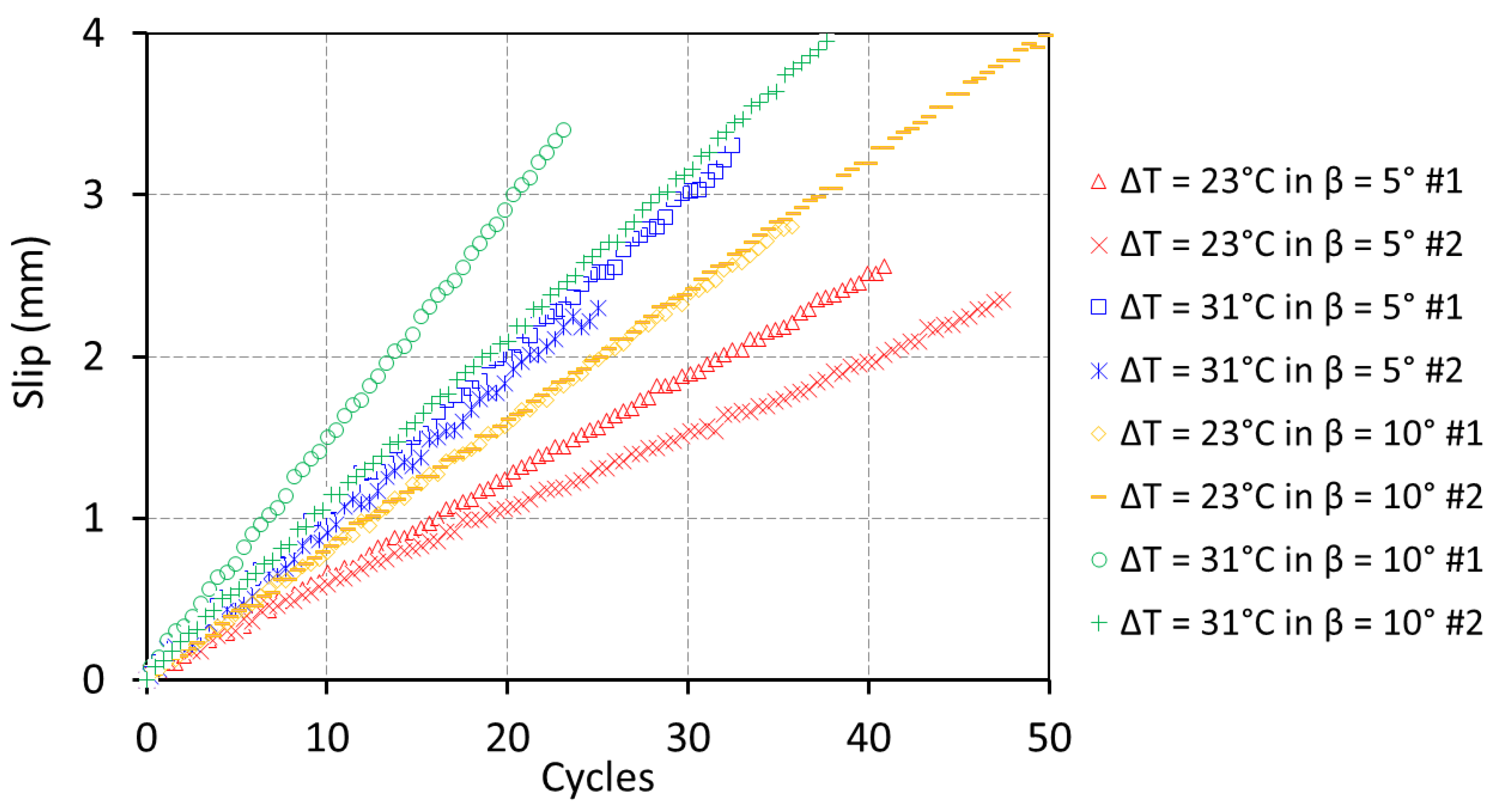

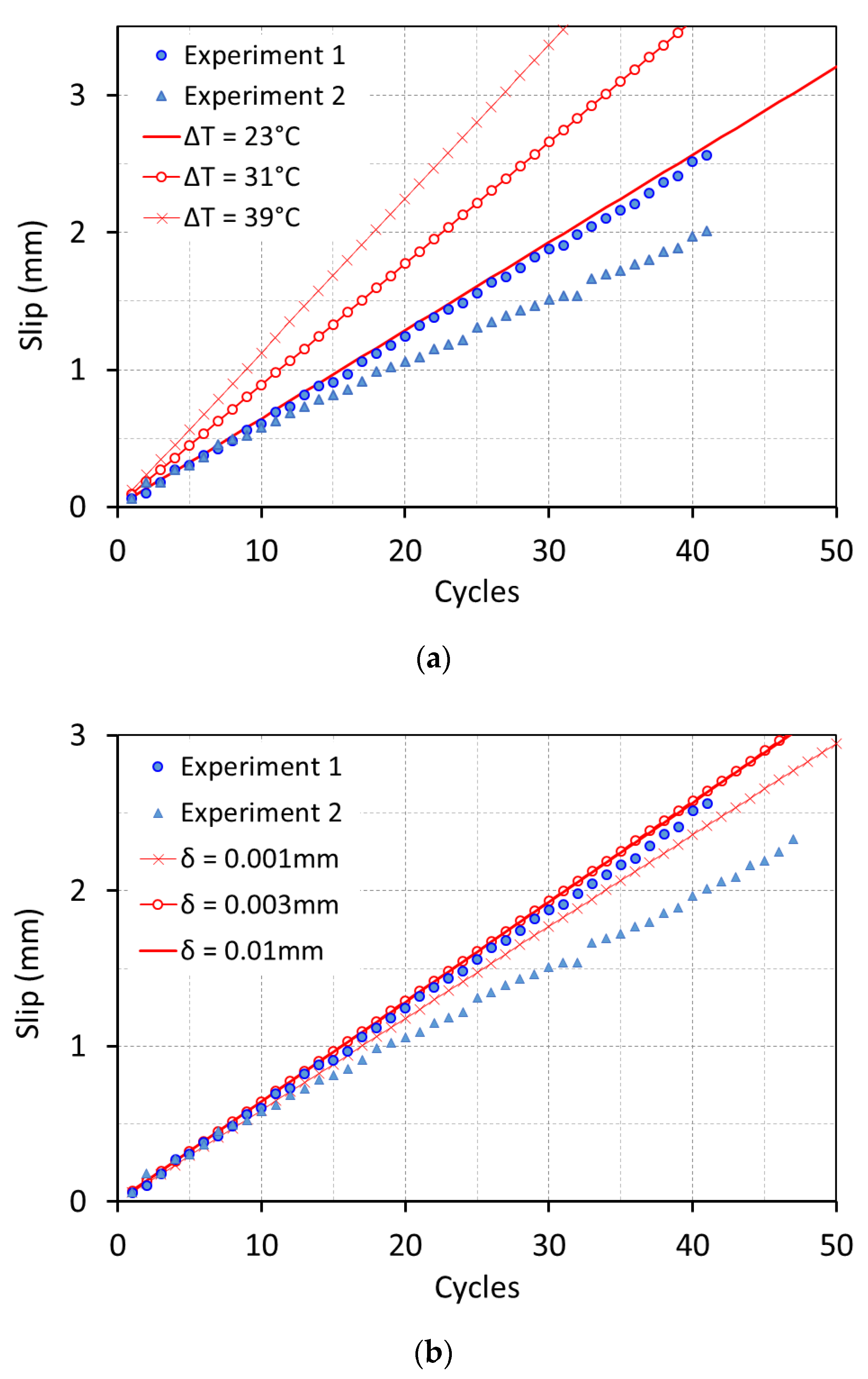

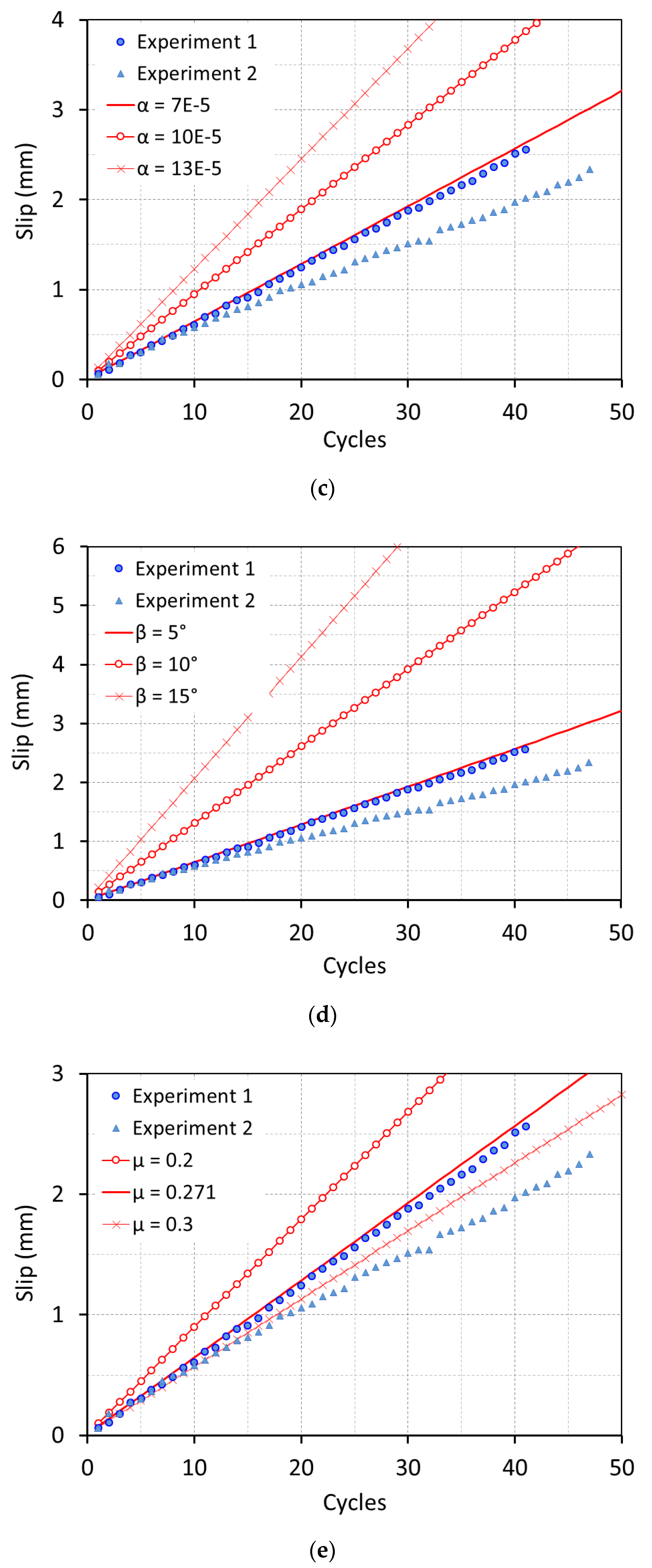

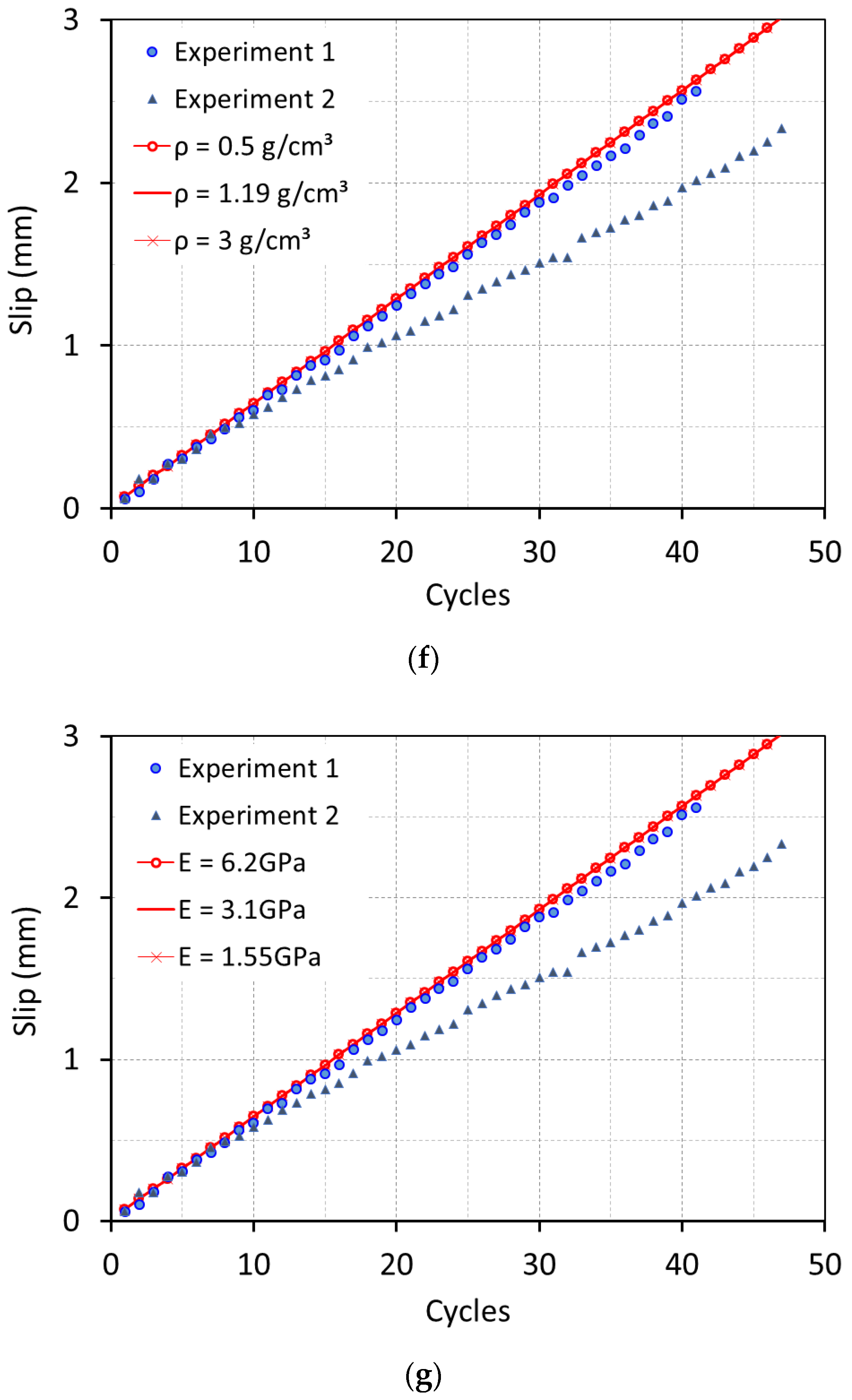

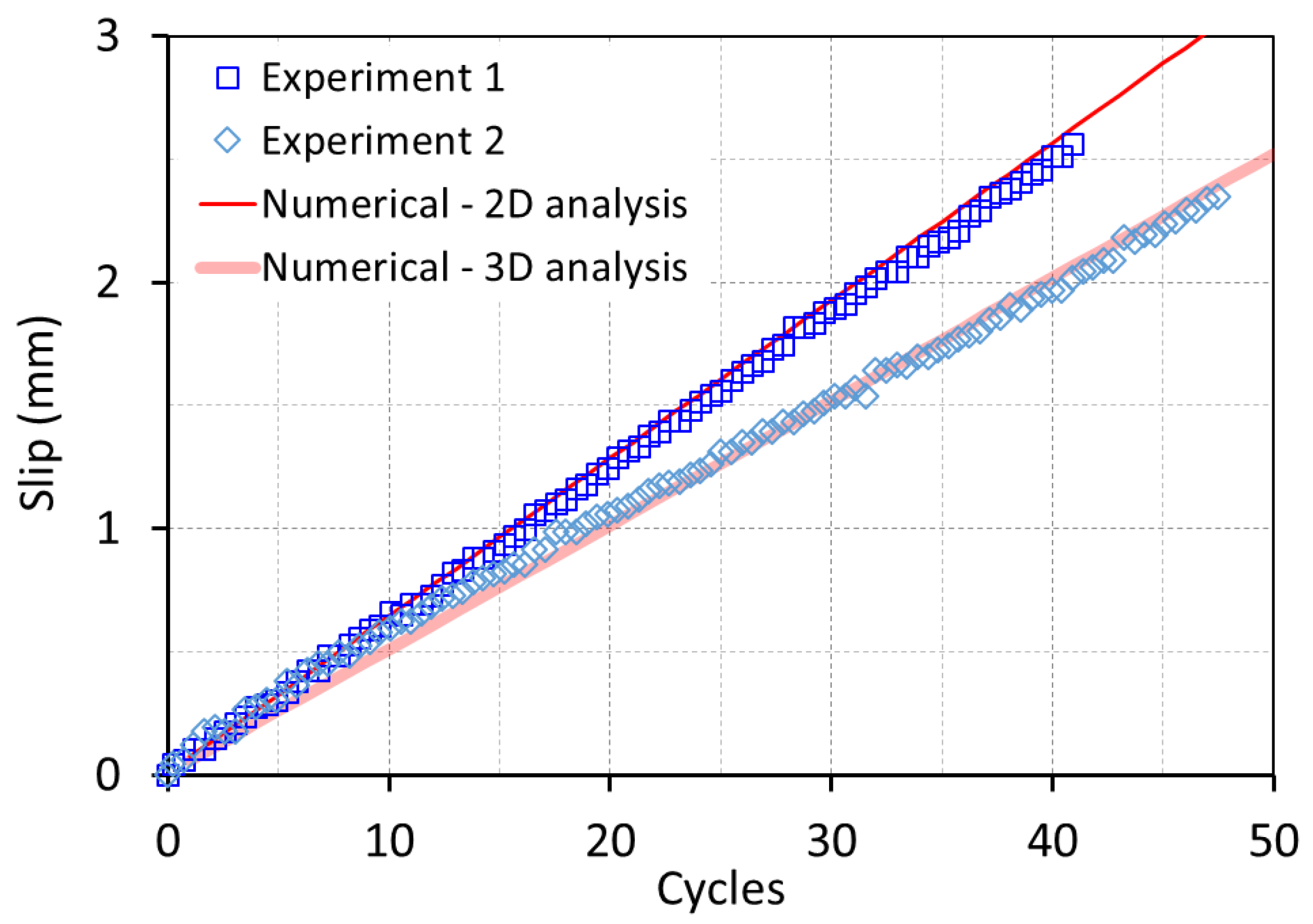

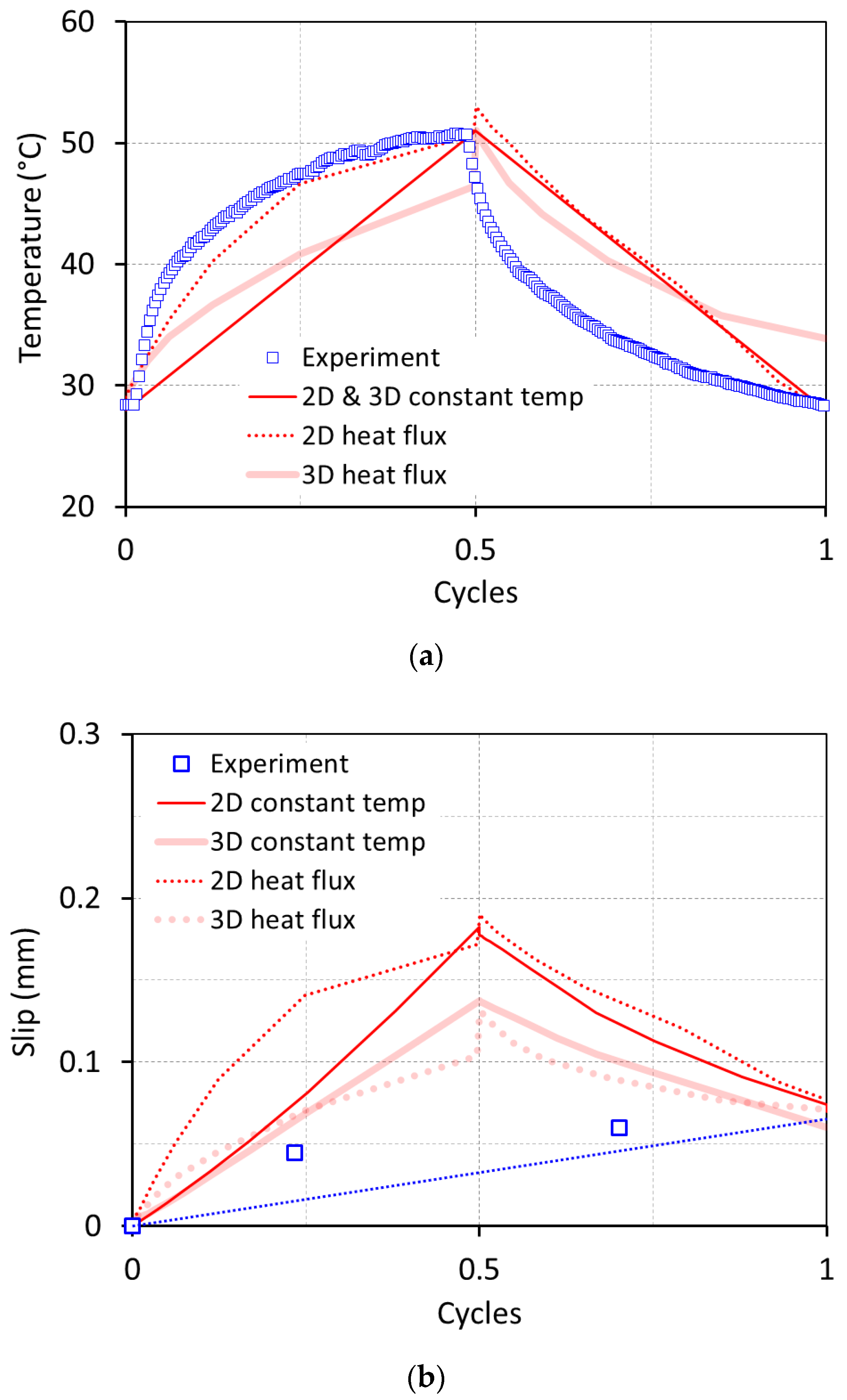

Experiments reveal that the acryl plate gradually slides down (i.e., slip accumulation) only with the temperature variations. Even though the simple experiment can demonstrate the actual occurrence of slip ratcheting even under mild temperature changes, it is still not clear how the slip between two materials continuously grows and how much amount of the slip can be estimated after a large number of cycles. Moreover, there is a practical limitation of the number of temperature cycles that can be applied during the experimental study (e.g., the presented experimental work takes 12 h to monitor a gradual slip ratcheting over 36 cycles). In this respect, numerical analysis or analytical approach that can reproduce the described experimental results would be a great alternative, which will enable us to explore a much larger number of cycles.

The finite element model is constructed accordingly in the plane strain condition using Abaqus (

Figure 5a). Note that a comparison between the two-dimensional plane strain and three-dimensional simulations is discussed in a later section. The acryl and wood in the simulation model are set as linear elastic materials with the representative mechanical and thermal properties listed in

Table 1. The interface is treated as linear elastic-perfectly plastic using the Coulomb frictional model. The coefficient of friction (

) and the elastic slip (

) are applied to the interface of those two materials. The wood is assumed not to deform against gravity nor temperature fluctuations, thus fully fixed in all directions, whereas the acryl plate as a sliding slab is not constrained at all. Similar to the experiment, the acryl plate is placed on the wood slope inclined at an angle of

, and only a gravitational acceleration is applied. Then, the temperature of the acryl plate is increased by

and then decreased by the same temperature change (

). The combination of temperature increase and decrease of the acryl plate is deemed one cycle of temperature fluctuation, and up to 50 temperature cycles are applied to the acryl plate during the numerical simulation. Similar to the experimental conditions, two cases of temperature changes (

and

) and two cases of the inclination angles (

and

) are considered in the simulations for comparison with the experimental outcomes. The slip accumulation is monitored at the front end of the acryl plate (

Figure 5a). Moreover, the stress values, along with the slip, are to be presented in the next section (following the definitions in

Figure 5b). That is,

is the normal stress acting parallel to the slope surface,

is the normal stress acting perpendicular to the slope surface, and

is the shear stress between the acryl and the wood. All of these stress values are monitored at the base of the acryl. The positive normal stresses represent tensile values as per traditional mechanics and the negatives are for compressive ones. The positive shear stress denotes downward shear stress on the acryl side, which is the same as the one shown in

Figure 5b.

Numerical Study—Slip Behavior

Upon the verification of the numerical model used for the thermally induced slip ratcheting in the previous section, the model now can be used to examine further how the interface strengths are mobilized during the slip ratcheting. We particularly focus on stress components and slip values at the interface in this section. The aim is to offer a better understanding of the behavior of the interface and the slip accumulation during temperature fluctuation. The coordinates for the stress components are shown in

Figure 5b; the axis parallel to the slope is

-axis, and the one perpendicular is

-axis.

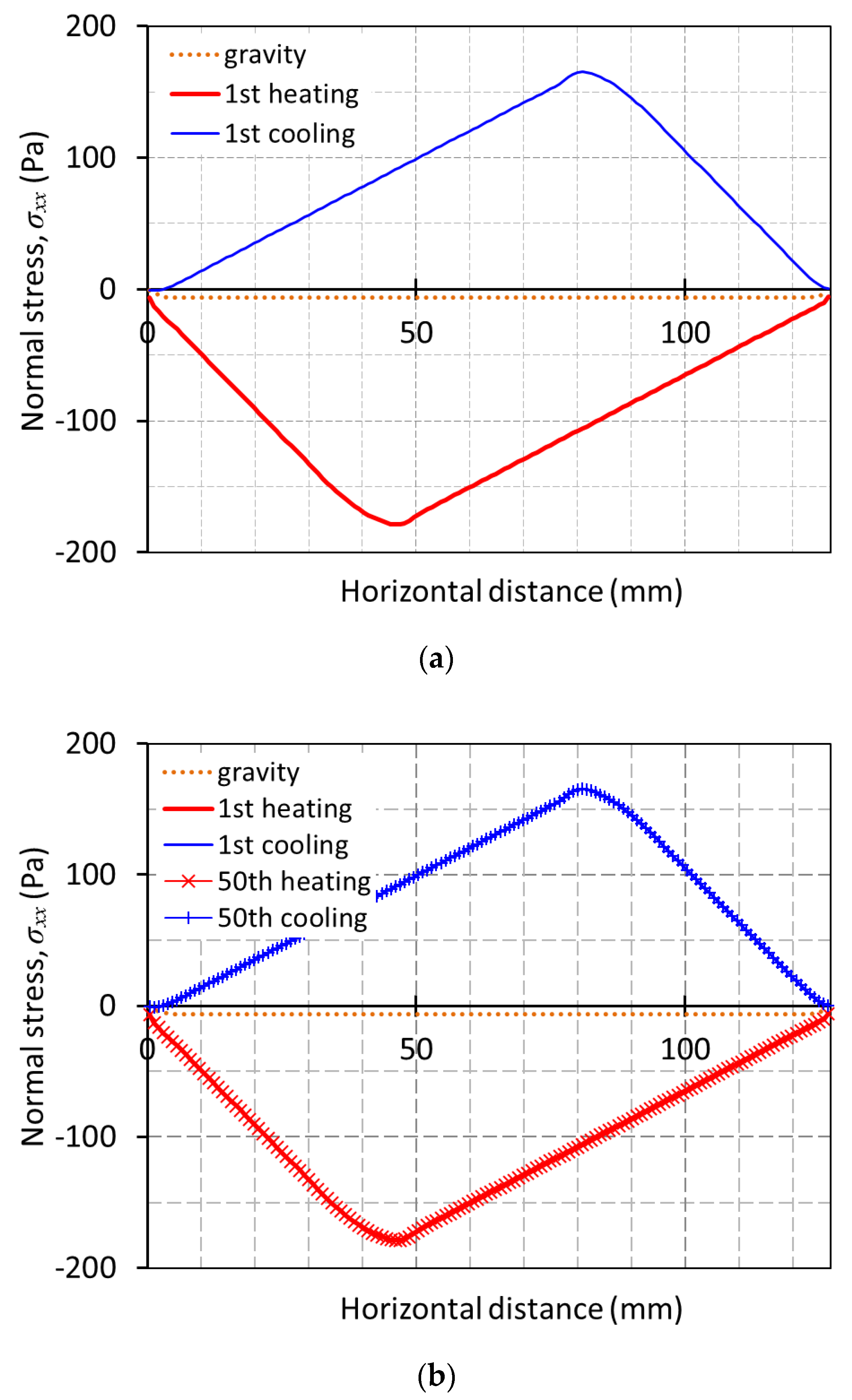

First, the distributions of normal stress in a direction parallel to the slope surface (

) on the acryl plate are shown in

Figure 8. Normal stress with gravitational loading only is presented as a dotted-orange line (

Figure 8), which magnitude is much smaller than that when any temperature changes are imposed. The distribution of normal stress with gravity appears nearly uniform, and the magnitude is around

. With a temperature increase (labeled as “heating”), the distribution of normal stress (

) becomes negative (compressive), non-uniform, and concave-up with approximately

of the peak at around

from the left end and nearly

at both left and right ends of the acryl plate (a red line in

Figure 8a). It implies that, when the acryl is heated, the entire acryl plate is under compressive stresses, caused by the constraint of the frictional resistance between the acryl and the wood, namely, interface shear strength against thermal expansion behavior.

Once the temperature of the acryl drops back to the initial value (labeled as “cooling”), the normal stress (

) becomes positive (tensile) and its distribution in the plate is concave-down with the peak of

around

from the left end of the acryl plate (a blue line in

Figure 8a). In contrast to the heating cycle, the entire acryl plate is under tensile stresses with the temperature drop, and this is because the shrinkage of the acryl plate is obstructed by the interface shear stress. It is also observed that the distribution shapes and the stress magnitudes do not change as the temperature cycle continues. For instance, the distributions at the 50th cycle of temperature fluctuation are essentially the same as those of the first cycle (

Figure 8b; the distributions at the first and 50th cycles are completely overlapped). With such a constant distribution of normal stresses, we can postulate that the locations of the maximum and the minimum normal stresses (i.e.,

and

from the left end, respectively) are approximately the “neutral points”. This will be discussed further in the next paragraph.

The distributions of normal stress in a direction perpendicular to the slope surface (

) at the base of the acryl plate is shown in

Figure 9. Similar to

in

Figure 8, the distribution shapes and the stress magnitudes of

also do not change during the 50 cycles of heating–cooling. The magnitude of

with gravitation loading only also more or less the same as those with temperature increase or drop, which is approximately

, the value calculated in

Section 2.2. There are small disturbances observed when the acryl is heated and cooled down; the amplitudes are up to

, which is much smaller than the base value (

). The locations of the disturbances of

coincide with the location of the peak

values, (i.e.,

and

from the left end, respectively).

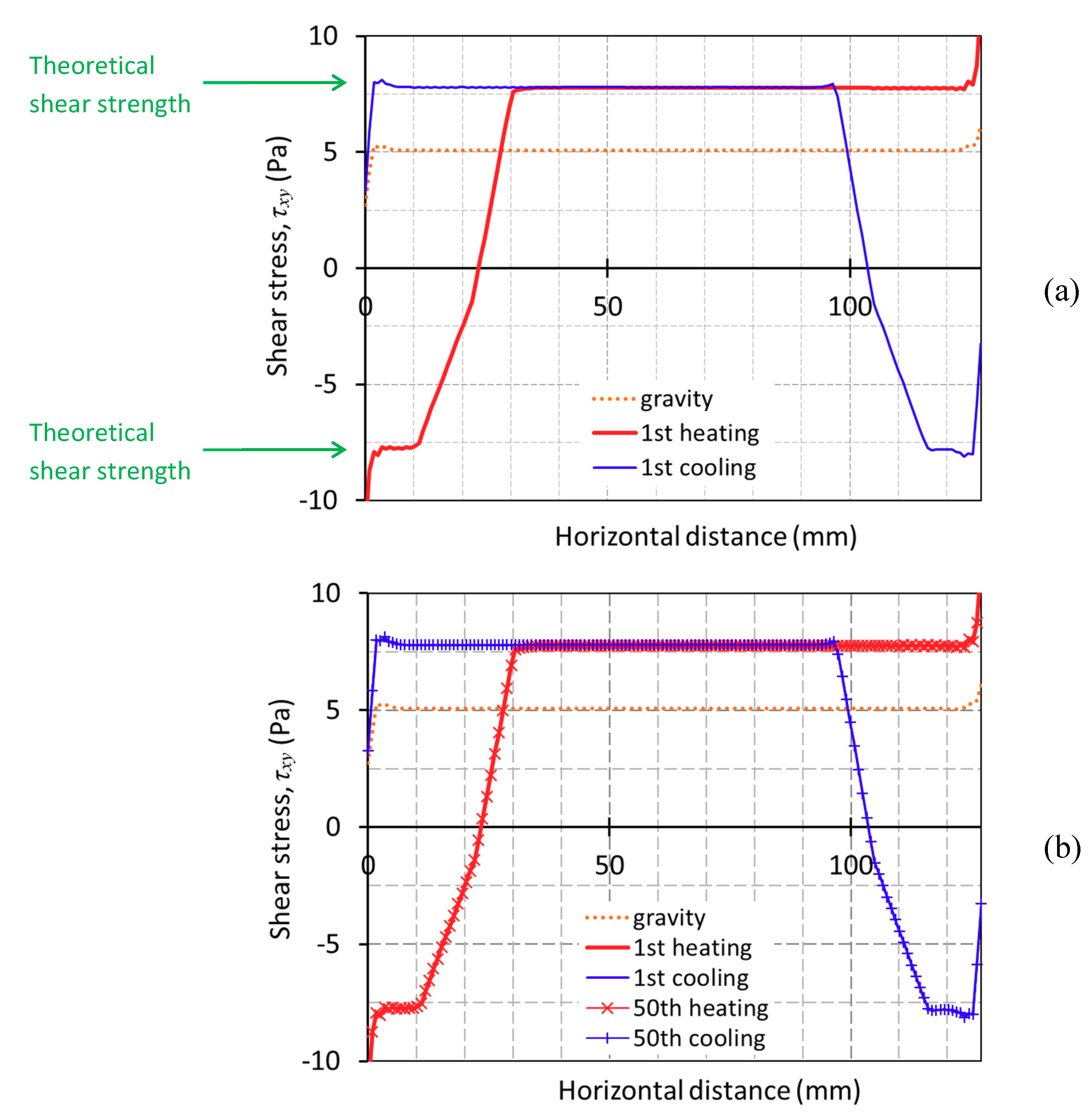

The distributions of interface shear stress (

) at the acryl-wood interface are presented in

Figure 10. Note that shear stress is positive for the downslope direction and negative for the upslope at the lower surface of the acryl plate. Shear stress only with the gravitational loading is also plotted in

Figure 10 (a dotted orange line), which appears nearly uniform and small in magnitude (~

). With a temperature increase (“heating”), the shape of interface shear stress distribution is similar to a step function with a slanted jump from the minimum to the maximum (a dashed line in

Figure 10a). The maximum and minimum values of shear stresses are nearly the same with the different signs, which implies that the interface shear stress reached its shear strength of

(note that

). Therefore, over the interval of

and

(from the left end, hereafter), the interface shear stress is approximately constant of

, and over the interval of

to the right end, it is constant

. Between

and

, the shear stress monotonically increases with zero at around

. Therefore, it can be inferred that a part of the acryl plate from the left end to

deforms upwards while the remaining part from

to the right end deforms downwards. Thus, the location of

can be considered as the “neutral point” when the acryl plate is heated, which is very close to

(determined from the normal stress distribution). Therefore, the estimate of

(determined from the shear stress distribution) is deemed as a more accurate one.

With the temperature drop (“cooling”), the shape of interface shear stress distribution is flipped over (a solid line in

Figure 10b) from that of the heating cycle, but with the different intervals for the maximum and minimum shear stresses. The interface shear stress is almost constant of

over the interval of

and

, and it is again constant at

over the interval of

to the right end. Between

and

, the shear stress decreases monotonically with zero at around

. Similar to the heating cycle, the location of

can be considered as the “neutral point” when the acryl plate is cooled down (

from the normal stress distribution). Moreover, like the normal stress distribution, the distribution of interface shear stress remains the same during the 50th temperature cycles, which implies the stress conditions will not change hereafter.

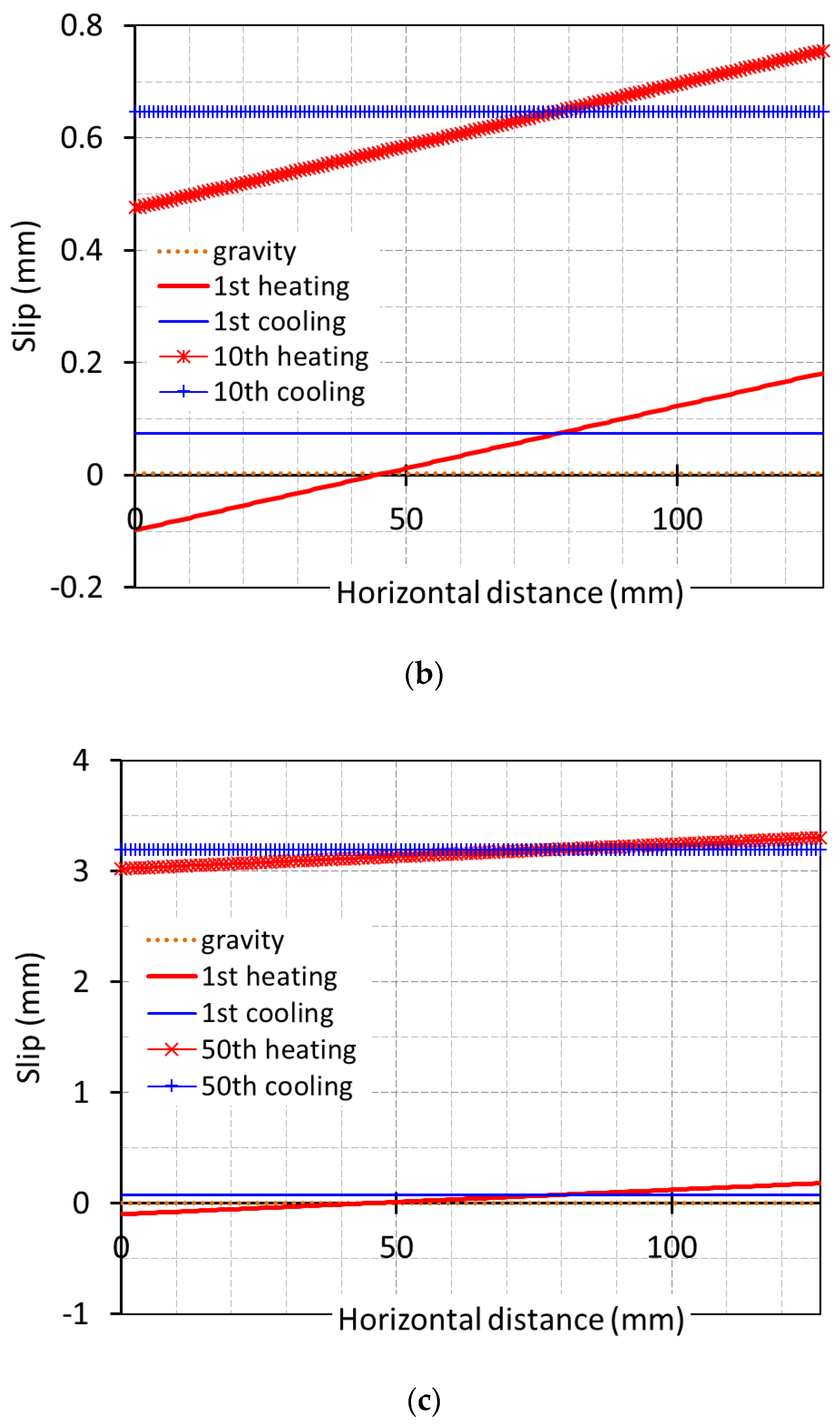

The distribution of the interface slips at the acryl-wood interface is described in

Figure 11. Positive values of the slip denote the downhill direction, whereas negative ones for the uphill movement. Slip by the gravitational loading only is negligible, as shown in

Figure 11a (a dotted line; approximately

). When the temperature is increased, the slip distribution at the interface is linear, from

to

(from the left end to the right, a dashed line in

Figure 11a). The location of zero slip appears to be approximately

, which coincides with the neutral point identified from the interface shear stress distribution (

Figure 10). When the acryl plate is cooled back, the slip distribution is flipped over from

to

(from the left end to the right, a dot-dash line in

Figure 11a), which shows another neutral point at

. The overall distribution of the slip after the combined heating–cooling cycle is approximately constant at

(a blue solid line in

Figure 11a), which is fundamentally an irrecoverable, residual slip that is also shown in

Figure 6b and

Figure 7.

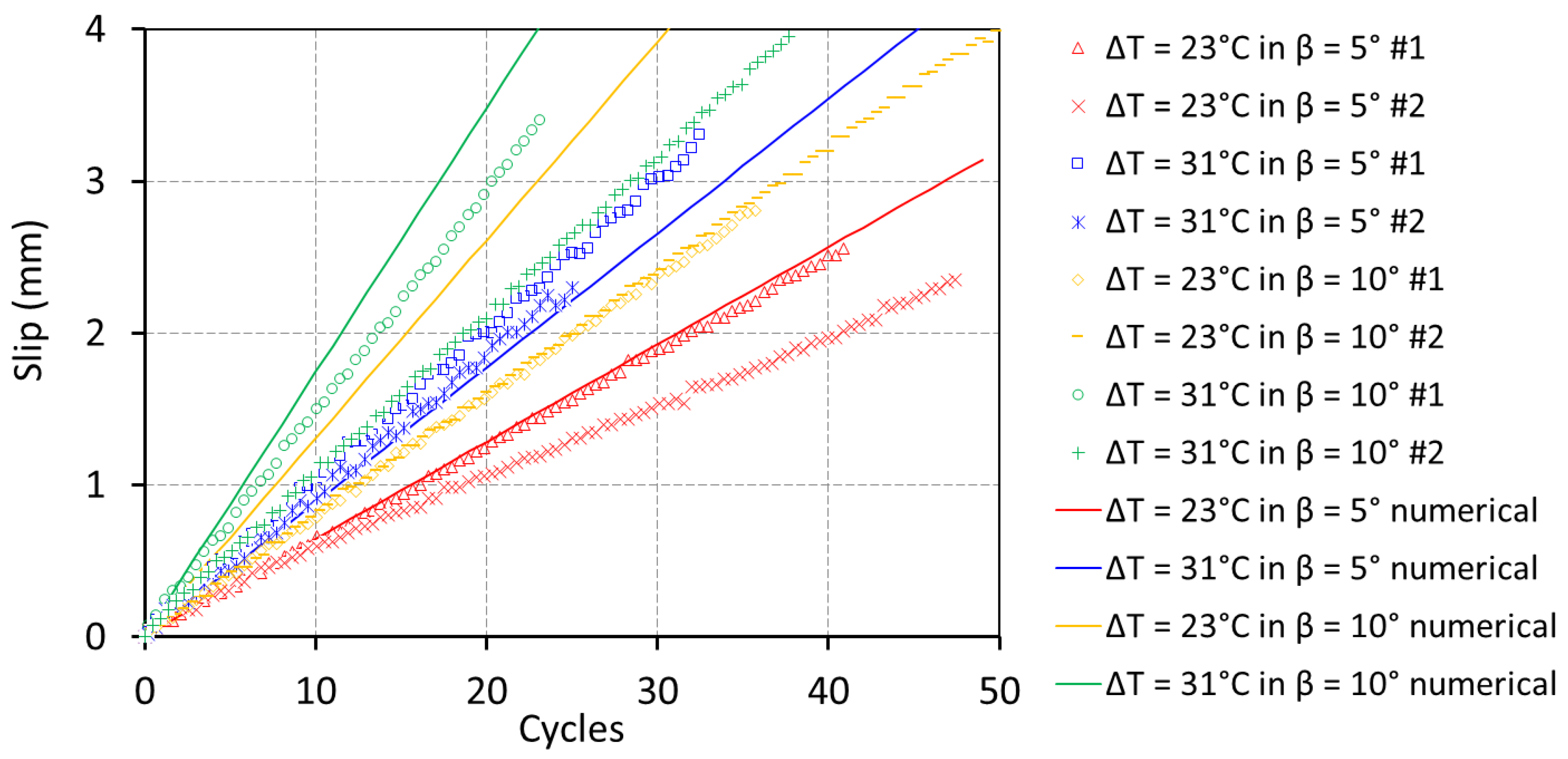

There is a major difference found between the stress distributions (i.e., normal and shear) and the slip distribution; the slip distribution has an increasing magnitude with the repetition of the temperature cycle, whereas the stress distribution does not. As noted earlier, the same stress distribution shape during the temperature cycles implies that the locations of the neutral points are the same. The irrecoverable slip occurs even from the first heating–cooling cycle, which implies that the slip will continue to accumulate as the temperature cycle repeats. Moreover, the magnitude of the irrecoverable slip at each heating–cooling cycle must be the same, given that the stress values are identical during all the cycles. Therefore, the irrecoverable slip will continuously grow with the temperature cycles, and it should be linearly growing. For instance, the irrecoverable slip is

with the gravity,

at the first cycle,

at the 10th cycle, and then

at the 50th cycle (solid lines in

Figure 11b,c), which is approximately

.

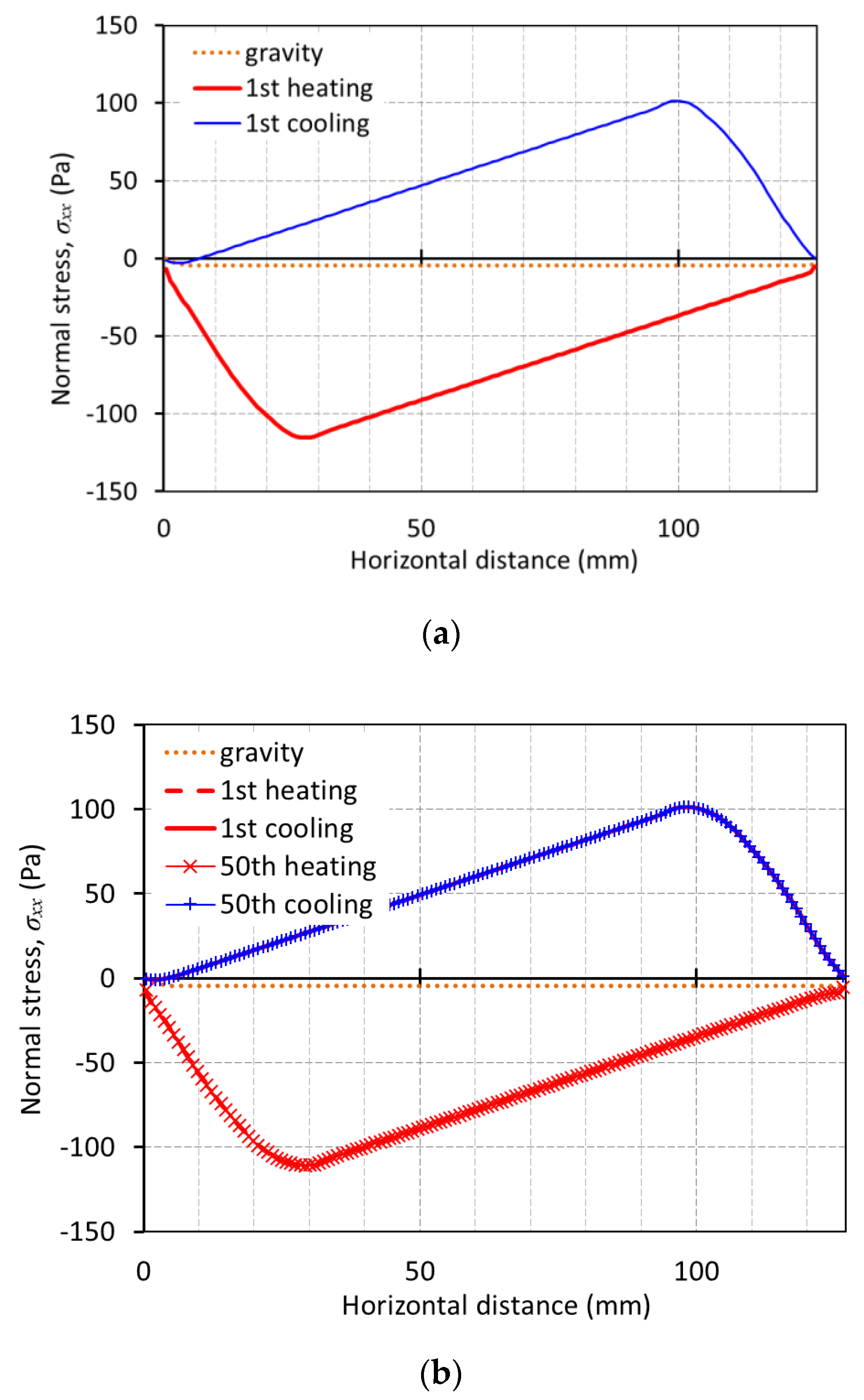

Similar features are also found in the different case with the higher temperature amplitude and slope angle,

in

slope (

Figure 12 through

Figure 13 and

Figure 14). The overall patterns of the normal stress (

), interface shear stress (

), and slip at the acryl-wood interface are found similar. However, the magnitudes of the stresses and the slips along with the neutral point positions are quite different from those from the previous condition (

in

slope). For example, the minimum normal stress is about

around

(from the left end hereafter) when heated, and the maximum value comes at about

around

when cooled down (

Figure 12). Zero interface shear stress is observed at around

and

when heated and cooled down, respectively, and the neutral points are identified as those locations accordingly. The intervals of the shear stress transition are between

and

and between

and

when heated and cooled down, respectively (

Figure 13). Moreover, after the first heating–cooling cycle, the residual slip is

(

slip with gravity), and it accumulates to

after 10 cycles, and to

after 50 cycles, which is approximately

(

Figure 14). Please be noted that the described features in the distributions of normal and stress forces and the slip values are also presented in [

13] to some extent.

As shown in those two cases of simulations, the magnitude of a residual slip is affected by the location of the neutral points. It helps to consider an extreme case where the neutral point is exactly at the middle of the acryl plate: that is, when the acryl is placed on a flat surface (), then the neutral point is always at the half of the plate during both heating and cooling conditions. Intuitively, no irrecoverable slip is expected in this case. Therefore, the flip of the neutral point about the center of the plate during the heating-and-cooling cycles is believed to be a primary reason for such a residual slip. Moreover, the irrecoverable slip would increase as the distance from the neutral point to the middle of the plate lengthens.

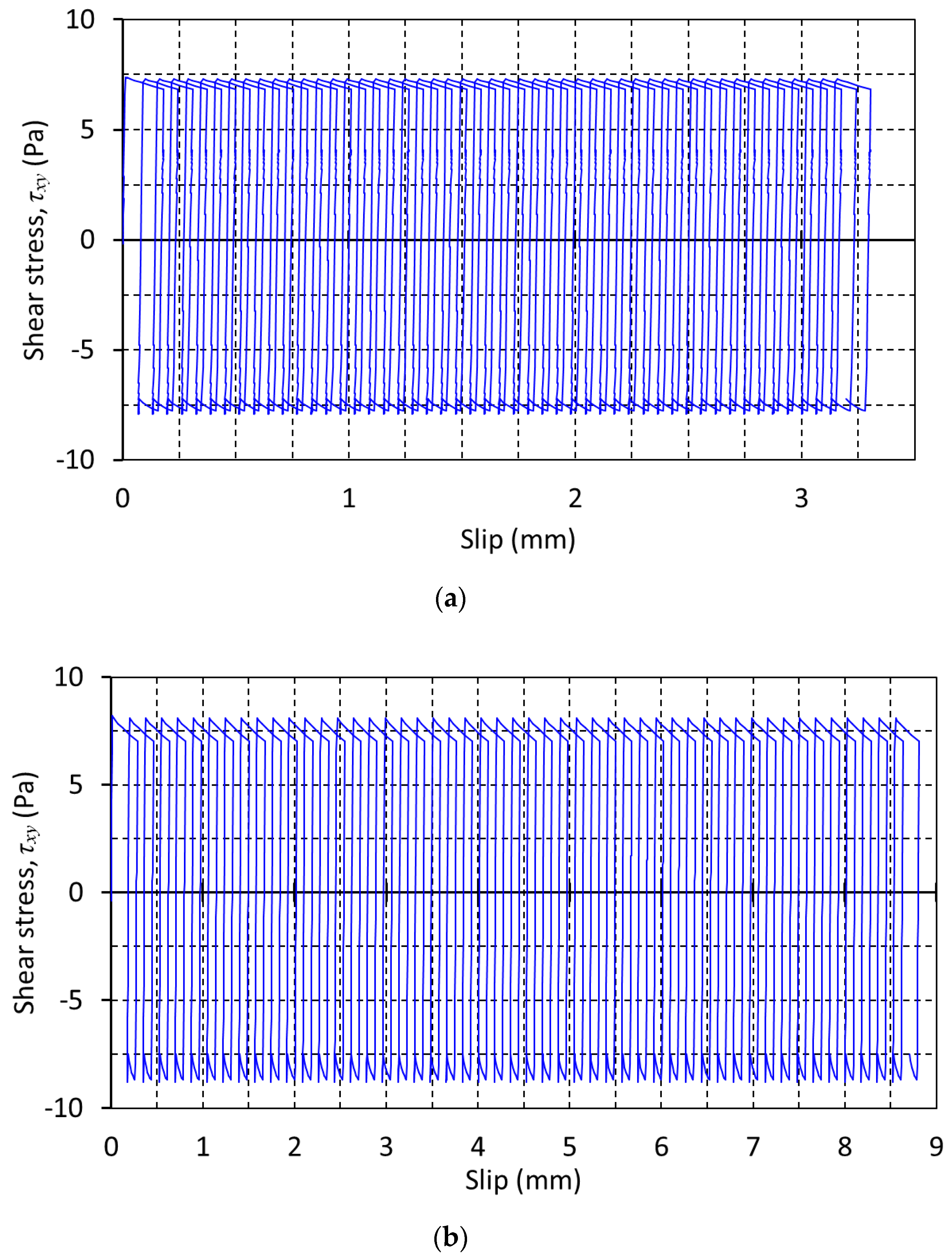

Lastly,

Figure 15 describes the stress–slip relations during the repetitive heating–cooling cycles. The magnitude of the interface slip continuously grows while the interface shear stress alternates only within the same maximum and minimum values. That is, with the same temperature fluctuations, the slip ratcheting would gradually occur and continue to accumulate during the temperature cycles.