Abstract

Traffic signal control plays a pivotal role in intelligent transportation systems, directly affecting urban mobility, congestion mitigation, and environmental sustainability. As traffic networks become more dynamic and complex, traditional strategies such as fixed-time and actuated control increasingly fall short in addressing real-time variability. In response, adaptive signal control—powered predominantly by reinforcement learning—has emerged as a promising data-driven solution for optimizing signal operations in evolving traffic environments. The current review presents a comprehensive analysis of high-impact reinforcement-learning-based traffic signal control methods, evaluating their contributions across numerous key dimensions: methodology type, multi-agent architectures, reward design, performance evaluation, baseline comparison, network scale, practical applicability, and simulation platforms. Through a systematic examination of the most influential studies, the review identifies dominant trends, unresolved challenges, and strategic directions for future research. The findings underscore the transformative potential of RL in enabling intelligent, responsive, and sustainable traffic management systems, marking a significant shift toward next-generation urban mobility solutions.

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation

The growing complexity of modern cyber-physical systems demands adaptive control mechanisms that ensure efficiency, resilience, and real-time responsiveness. Such mechanisms are increasingly employed across advanced IoT ecosystems, including building automation [1,2,3,4,5], manufacturing lines [6,7,8], and robotic procedures [9,10,11], where systems often encounter unpredictable dynamics. In such contexts, traditional control approaches frequently fall short, necessitating more adaptable strategies capable of responding dynamically to evolving operational conditions. Traffic networks constitute another complex cyber-physical IoT domain where real-time disruptions—ranging from congestion and accidents to fluctuating pedestrian activity—pose significant control challenges. Urbanization and rising vehicle volumes further strain conventional coordination methods, such as fixed-time (FT) and actuated signal control (AC), which lack the flexibility to accommodate such dynamic environments [12,13,14,15]. This growing demand for real-time, intelligent signal management has driven the adoption of adaptive traffic signal control frameworks aimed at mitigating economic losses, reducing emissions, and addressing broader inefficiencies in urban mobility [16,17,18,19].

Traffic signal control (TSC) has attracted research attention since the mid-20th century, initially relying on fixed-time scheduling based on historical data [17,20]. Later, actuated systems emerged, using sensor feedback to make localized adjustments. However, these conventional strategies often struggle under irregular traffic conditions such as unplanned congestion, events, or accidents [21,22,23]. Advances in AI and machine learning have since paved the way for data-driven systems capable of real-time, self-adaptive control [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31].

Such adaptive traffic signal control (ATSC) frameworks may be broadly categorized as either model-based or model-free. Model-based approaches employ mathematical models and optimization algorithms that integrate both real-time sensor input and historical trends [12,20,32,33,34]. In TSC contexts, such practices optimize signal timing across interconnected intersections based on predicted flow patterns [35,36,37]. In contrast, model-free methods utilize machine learning to derive optimal control strategies through interaction, without relying on predefined system models [38]. Such systems learn control policies directly from traffic data and real-time environmental feedback [39]. Reinforcement learning (RL) encompasses both model-free and model-based approaches, enabling agents to either learn optimal behaviors directly through interaction or by utilizing predictive models of the environment to guide decision making. In the context of large-scale cyber-physical systems, model-free RL approaches have gained particular prominence due to their flexibility and ability to handle complex, dynamic urban environments. To this end, the applications of model-free RL range from smart building operation [40,41,42,43,44] and industrial automation [45,46,47,48] to robotic coordination [49,50,51,52] and traffic network management [16,53,54,55]. Unlike traditional control frameworks, RL enables continuous adaptation, aiming to enhance traffic efficiency by reducing delays, minimizing stops, and improving overall flow. Early RL applications in traffic control typically focused on isolated intersections with single-agent designs. As the field matured, advanced techniques—such as deep reinforcement learning (DRL) and multi-agent RL (MARL) frameworks—were introduced to address the increasing coordination complexities across entire traffic networks [12,16]. Over the past decade, such advanced RL-based methods have evolved substantially, incorporating richer state representations, refined reward functions, and collaborative learning strategies for managing diverse, large-scale traffic systems [16,53,54,56].

In light of the growing need for intelligent traffic management, the current review systematically examines the most significant RL-based approaches developed between 2015 and 2025, with a specific focus on urban traffic signal optimization at intersections. It covers a wide range of aspects, including RL algorithms and control philosophies, agent structures, baseline control strategies, reward function architectures, performance indicator types, intersection classifications, simulation tools, and training methodologies. Through statistical analysis, the study identifies prevailing trends, uncovers key challenges, and highlights future research directions to advance the field.

1.2. Literature Analysis Approach

This review analyzes the key principles, RL frameworks, optimization strategies, and performance outcomes of RL-based traffic signal management approaches developed over the past decade. To ensure a structured and meaningful analysis, studies are categorized by RL methodology (value-based, policy-based, and actor-critic), training paradigms, intersection control schemes, and coordination strategies in multi-agent systems. Additionally, aspects such as simulation environments, evaluation metrics, and real-world applicability are examined to offer a holistic perspective on RL-driven traffic signal optimization. In detail, the literature analysis approach may be described by the following steps:

- Study Selection: To ensure the scientific robustness of this review, a thorough selection methodology was applied, drawing exclusively from Scopus—and Web of Science—indexed peer-reviewed journals and conferences. An initial set of over 250 publications was screened based on abstracts, from which the most pertinent studies were shortlisted for full analysis. The selection process adhered to multiple quality criteria: (a) Citation Threshold: Only studies with at least 30 citations, excluding self-citations, were considered to guarantee recognized academic impact, verified through Scopus at the time of review. In addition, given their recent publication, the studies from 2023 and 2024 constituted an exception, with their threshold set at 10 citations. (b) Topical Focus: Only research directly addressing RL-driven traffic signal control was included, excluding unrelated works on traffic estimation, non-RL-based signal systems, or broader urban mobility management. (c) Peer-Review Status: Only fully peer-reviewed articles and top-tier conference papers from publishers like Elsevier, IEEE, MDPI, and Springer were selected, with pre-prints and non-peer-reviewed studies omitted. (d) Methodological Transparency: Papers were required to clearly document their RL setup, control objectives, evaluation metrics, and comparative benchmarking. (e) Methodological Diversity: A balanced representation of value-based, policy-based, and actor-critic RL research applications was maintained, covering varying signal traffic control cases.

- Keyword Strategy: A targeted keyword strategy was designed to maintain focus on reinforcement learning applications for traffic signal control. Primary search terms included “Reinforcement Learning for Traffic Signal Control”, “RL-based Traffic Light Optimization”, “Adaptive Traffic Signal Control using RL”, “Deep Reinforcement Learning for Traffic Signal Management”, “Reinforcement Learning for Traffic Signal Control”, and “RL-based Adaptive Traffic Management”. Care was given to select phrases closely aligned with signal control tasks, avoiding broader traffic management or routing topics.

- Data Categorization: Each selected study was carefully classified across multiple dimensions to enable thorough and structured analysis. The categorization included the RL methodology type and specific algorithms employed, the agent structure (single-agent vs. multi-agent control), the nature of the reward function, the performance metrics used for evaluation, and the baseline control strategies adopted for comparison. Furthermore, the scale of the traffic environment—whether single intersections or larger networks—was documented. Finally, the simulation platforms utilized for model training and validation were systematically recorded to assess the realism and comparability of the reported results.

- Quality Assessment: A systematic evaluation process was applied to ensure the inclusion of impactful and credible research. Specifically, citation metrics were used as a primary filter, requiring a minimum of 30 citations (excluding self-citations), with data sourced from Scopus to guarantee reliability. Studies published in high-impact journals and leading conference proceedings were favored. Beyond citation counts, the academic profile of the authors was assessed, focusing on their contributions to the fields of reinforcement learning and traffic signal control. Special emphasis was placed on authors with proven expertise, evidenced by publications in top-tier venues, contributions to the development or refinement of RL techniques for control problems, and affiliations with prominent transportation research centers or AI laboratories. This multi-faceted evaluation helped to prioritize studies offering substantial and credible advancements in RL-based traffic signal control.

- Findings Synthesis: Key insights were systematically organized into thematic categories to enable clear comparisons across different RL methodologies applied to traffic signal control. This structured synthesis not only contributed to a comprehensive understanding of the field’s development but also enabled the generation of statistical analyses across different study attributes, as well as the identification of emerging trends and persistent challenges within the domain. Furthermore, it provided a solid foundation for formulating informed future research directions, highlighting gaps in current approaches and proposing potential advancements in RL-driven traffic signal control optimization.

The following Figure 1, summarizes the above mentioned literature analysis steps:

Figure 1.

Literature analysis approach.

1.3. Previous Work

Several reviews have examined various facets of traffic signal control, ranging from classical optimization techniques and intelligent transportation systems to modern machine-learning-based solutions. Many focus on reinforcement learning and its role in optimizing signal timing and traffic flow. Wang et al. [57] offered a comprehensive overview of deep reinforcement learning applications in traffic signal control, analyzing DRL architectures, methodologies, and simulation tools. Their findings emphasized DRL’s strength in managing high-dimensional state spaces and alleviating congestion. Yau et al. [58] reviewed core RL algorithms for traffic signal control, focusing on representations of state, action, and reward, as well as computational efficiency. Their work identified major advancements, compared RL techniques, and outlined future directions. Miletic et al. [59] provided an extensive review of RL methods for adaptive traffic signal control, showcasing the advantages over traditional approaches and exploring multi-agent systems, DRL, and the influence of connected and autonomous vehicles (CAVs). The review concluded with open challenges and prospective research paths. Zhao et al. [60] examined recent developments in DRL for traffic signal control, organizing methods by algorithm type, model setup, and application scenario. Their study addressed previous survey gaps by analyzing state-of-the-art advancements from the past five years and highlighting future research opportunities in DRL-powered traffic management.

1.4. Contribution and Novelty

This review provides a comprehensive and structured examination of RL applications in traffic signal control, distinguishing itself from the existing literature through several key contributions. Unlike previous reviews that broadly discuss AI-driven traffic management, this study focuses specifically on RL-based control frameworks designed to optimize traffic signal timing, coordination, and adaptation across urban road networks.

A significant novelty of this work concerns its large-scale, in-depth assessment of RL-based traffic signal control methodologies, systematically summarizing, classifying, and analyzing a substantial number of influential studies published between 2015 and 2025. To ensure a high-impact evaluation, the current review prioritizes research contributions that have gained significant citations and practical relevance (more than 20 citations according to Scopus), allowing for a rigorous synthesis of key findings and trends in RL-driven traffic management. This work begins by illustrating the mathematical foundations of the most prominent RL methodologies for traffic signal control. It then presents detailed summary tables of the most influential studies, enabling researchers and practitioners to efficiently compare RL techniques, performance metrics, and control strategies.

Beyond summarizing existing approaches, this review identifies and classifies RL applications based on essential key elements, offering a structured comparison of different methodologies, based on methodology type, agent architectures, reward function analysis, baseline control, performance benchmarks, intersection type, and simulation environment. By going beyond a descriptive review, this study offers a critical evaluation of the concerned methodologies, providing statistical analysis for each evaluation attribute as well as valuable insights into existing challenges, emerging trends, and potential future directions in RL-driven traffic signal control. The following Table 1 summarizes the different evaluation aspects that current and previous works analyze.

Table 1.

Contribution comparison between current and previous works considering the different evaluation attributes.

Through this structured and in-depth approach, the current effort serves as a foundational resource for advancing intelligent, adaptive traffic signal management, paving the way for smarter, more efficient urban mobility solutions.

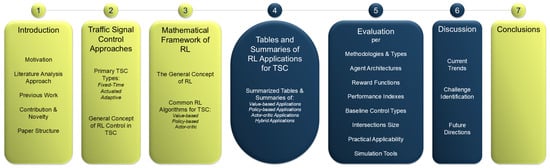

1.5. Paper Structure

As depicted in Figure 2, this paper is organized as follows: Section 1 introduces the motivation behind this review, outlines the methodology for literature analysis, examines prior research efforts, and highlights the key contributions and novelty of this study. Section 2 provides an overview of RL fundamentals in the context of traffic signal control, discussing general RL-based strategies applied in intelligent transportation systems. Section 3 explores the core RL methodologies used in traffic light signal management, presenting a generalized mathematical framework and categorizing approaches based on value-based, policy-based, and actor-critic algorithms. Section 4 examines the most influential studies on RL-based traffic signal optimization from 2015 to 2025, summarizing their key characteristics and findings in tabular format for comparative analysis. Section 5 provides an in-depth evaluation of RL-based traffic control methods, assessing their effectiveness based on critical key elements, including methodology type, multi-agent integration, reward function, baseline control, performance index, and simulation tools. Section 6 identifies, summarizes, and analyzes the emerging trends and challenges in RL-driven traffic signal control, highlighting also the potential research directions for future advancements in the field. Section 7 concludes the review by summarizing key insights and presenting final reflections on RL’s impact on adaptive and intelligent traffic management. Figure 2 portrays the overall paper structure.

Figure 2.

Paper structure.

2. Traffic Signal Control Approaches

2.1. Primary TSC Control Types

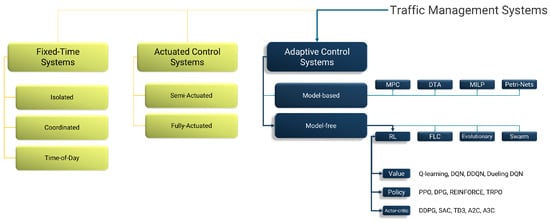

Traffic signal control frameworks play a critical role in managing urban mobility, ensuring safety, and optimizing intersection efficiency. Such traffic management approaches may be broadly classified into three main categories: fixed-time (pre-timed) control, actuated control, and adaptive control, each comprising various subtypes (see Figure 3). More specifically:

Figure 3.

Traffic management systems classification: fixed-time, actuated control, and adaptive control management systems.

- Fixed-Time (Pre-Timed) Control: This state-of-the-art approach operates on predetermined schedules, assigning fixed durations to signal phases based on historical traffic patterns [61]. While effective in environments with consistent flows due to its simplicity, it lacks adaptability to real-time conditions. Consequently, it performs poorly during disruptions such as accidents, special events, or sudden demand surges. Subcategories include [61,62,63]:

- Isolated Fixed-Time Control: Each intersection follows a standalone schedule with no inter-coordination.

- Coordinated Fixed-Time Control: Intersections are synchronized to enable green wave progression along corridors.

- Time-of-Day Control: Schedules vary by time period but remain non-responsive to live traffic conditions.

Despite its straightforwardness, FT control often leads to inefficiencies in dynamic traffic scenarios [64]. - Actuated Control: These state-of-the-art systems adjust signal timings based on real-time inputs from sensors like loop detectors, cameras, or infrared devices [65]. They may be typically classified as [66,67]:

- Semi-Actuated Control: Detection is installed on minor roads, allowing the major road to remain green until a vehicle is detected on the minor approach [68].

- Fully Actuated Control: Sensors monitor all approaches, enabling dynamic adjustments from all directions based on traffic conditions. This setup suits areas with unpredictable traffic and enhances flow compared to fixed-time systems [69].

However, actuated systems operate locally and lack coordination across intersections, limiting their network-level optimization capabilities [58]. - Adaptive Control: Adaptive traffic signal control (ATSC) systems represent the most advanced form of signal management. They are able to continuously monitor traffic in real time and apply algorithmic models to optimize signals across networks [70], aiming to reduce delays and adapt to fluctuating demand [39]. Subclasses include:

- Model-Based Optimization Systems: These rely on mathematical models to forecast traffic and adjust timings accordingly, using techniques such as model predictive control [37,71], dynamic traffic assignment [72,73], mixed-integer linear programming [74,75], and Petri nets [76].

- Model-Free Optimization Systems: Employing AI methods like reinforcement learning [77,78], fuzzy logic [79,80], evolutionary algorithms [81,82], and swarm intelligence [83,84,85], these systems learn directly from traffic data, adjusting without predefined models [86].

Model-based systems are preferred for structured environments, while model-free methods excel in complex, dynamic scenarios.

Figure 3 illustrates the classification of traffic management systems, with a focus on adaptive control and, specifically, on common model-free RL approaches. It presents key algorithm types—value-based: Q-learning (QL), deep Q-network (DQN), double deep Q-network (DDQN), dueling DQN; policy-based: proximal policy optimization (PPO), deterministic policy gradient (DPG), Monte Carlo policy gradient (REINFORCE), trust region policy optimization (TRPO); and actor-critic: deep deterministic policy gradient (DDPG), soft actor-critic (SAC), twin delayed DDPG (TD3), advantage actor-critic (A2C), asynchronous advantage actor-critic (A3C)). Section 3 provides a mathematical and conceptual overview of such algorithms.

2.2. General Concept of RL Control in TSC

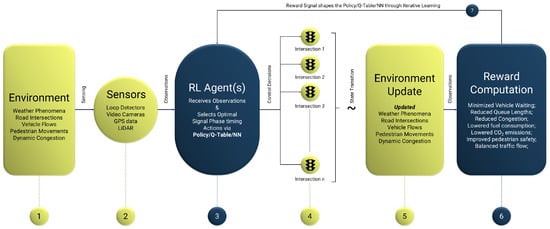

In RL-based traffic signal control, the decision-making process is structured around key components that interact dynamically to optimize traffic flow. The overall operation of RL control within a traffic signal control may be described through the following key steps (see Figure 4):

Figure 4.

General concept of reinforcement learning in traffic signal control.

- Environment: The traffic network constitutes the environment in which the RL agent operates. It may include intersections, vehicle and pedestrian flows, sensors, and external disturbances like weather or sudden congestion. The RL agent does not control this environment directly but learns to respond to its dynamics by optimizing signal timings.

- Sensors: Real-time monitoring is enabled through loop detectors, video feeds, GPS data, LiDAR, and connected vehicle systems. Such sensors capture observations—such as queue lengths, arrival rates, and pedestrian activity—that inform the RL agent’s decisions.

- RL Agent(s): Acting as the system’s intelligence, the RL agent evaluates incoming traffic data and determines optimal signal phases. Depending on the method used (value-based, policy-based, or actor-critic), it learns to minimize congestion, delays, and emissions through continuous interaction with the environment.

- Control Decision Application: Once an action is selected, the system implements signal adjustments—such as extending green times, skipping phases, modifying cycle lengths, or coordinating multiple intersections—based on the agent’s output.

- Environment Update: After applying the control decisions, the environment evolves. Vehicles move, congestion shifts, and new traffic enters, resulting in a new state that becomes the input for the agent’s next decision.

- Reward Computation: The system evaluates the agent’s decision using predefined metrics. Typical reward functions assess reductions in waiting time, queue lengths, fuel consumption, emissions, and improvements in pedestrian safety and traffic balance.

- Reward Signal Feedback: The computed reward is fed back into the RL algorithm, refining its policy. Through this iterative process, the agent improves its control strategy, enabling real-time, adaptive signal management.

Through continuous learning and real-time feedback, RL-based traffic signal control frameworks surpass traditional FT and AC effectiveness—especially in large-scale dynamic traffic scenarios—offering more efficient, responsive, and sustainable urban traffic solutions.

3. Mathematical Framework of Reinforcement Learning

RL frames traffic signal control as a Markov decision process (MDP), where an agent interacts with the traffic environment to learn optimal signal policies through trial-and-error. This is particularly advantageous for dynamic traffic conditions, allowing continuous adaptation to real-time variations such as vehicle density, queue lengths, and arrival rates. Over time, RL-based systems outperform traditional approaches by offering more responsive, resilient, and sustainable urban mobility solutions. This section explores the mathematical foundation of RL in traffic control, detailing the roles of state representation, action space, reward function, and training paradigms in enabling intelligent traffic management.

3.1. The General Concept of RL

The mathematical structure of RL may be formalized via the MDP framework, defined as the tuple [87]. Here, S is the set of environment states; A is the set of possible actions; represents the probability of transitioning to state from s under action a; denotes the reward for taking action a in state s; and is the discount factor balancing immediate and future rewards.

The objective is to maximize the cumulative return by learning a policy that selects actions to maximize expected returns: . The action-value function is defined as:

This function is updated using methods like Q-learning:

where denotes the learning rate.

3.2. Common RL Algorithms for Traffic Signal Control

Reinforcement learning algorithms in traffic control may be classified into three core types [43]: value-based, policy-based, and actor-critic methods, each offering distinct mechanisms for optimizing traffic performance.

3.2.1. Value-Based Algorithms

This RL type estimates the expected return of actions in specific traffic states using a value function, selecting actions that maximize expected rewards [88]. Value-based RL has been effective for discrete tasks such as phase selection or green-time allocation, though scalability becomes an issue in large or continuous action spaces. Common examples include Q-learning (QL) and deep Q-networks (DQNs) [43,88]:

- Q-Learning: An off-policy algorithm that iteratively updates an action-value function independently of the current policy [89]. Suitable for single-intersection control, it learns state-action values via:QL is efficient in discrete environments but struggles with high-dimensional networks [90].

- Deep Q-Networks: DQN enhances Q-learning by approximating the Q-function with deep neural networks. Techniques like experience replay and target networks improve training stability [91,92], enabling coordination across multiple intersections [93]. The update rule is as follows:

3.2.2. Policy-Based Algorithms

This algorithm type bypasses value estimation by directly optimizing the policy. Ideal for continuous action spaces, they support fine-grained control like dynamic phase timing [94]. While more flexible in complex environments, they require precise hyperparameter tuning. PPO stands out for its balance of stability and efficiency [95].

- Proximal Policy Optimization: PPO constrains policy updates to prevent training instability. Widely used in multi-intersection control, it balances exploration and exploitation in large-scale networks [96]. The clipped objective function may be expressed as:with and as the advantage function [97].

3.2.3. Actor-Critic Algorithms

Combining elements of both value and policy RL types, the actor-critic type uses an actor to propose actions and a critic to evaluate them [43,98]. Such an architecture offers both stability and efficiency, making it suitable for large, complex traffic networks [98]. Notable examples include:

- Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient: The DDPG methodology is mostly suited for continuous control tasks, such as adjusting green durations in real time. It updates the critic and actor as follows:While powerful, DDPG is sensitive to tuning [88,99].

- Soft Actor-Critic: The SAC methodology integrates entropy into the reward function, encouraging exploration and improving robustness in multi-agent settings [100]. Its objective includes an entropy term:

- Advantage Actor-Critic: A2C improves training by incorporating an advantage function to reduce variance:A2C has shown effective results in real-time adaptive control with reduced training variance [101,102], especially in coordinated multi-agent systems.

4. Attribute Tables and Summaries of RL Applications

This section provides a structured analysis of RL applications in TSC from 2015 to 2025. Each subsection offers a high-level overview, of Value-based, Policy-based, Actor-Critic and Hybrid high-impact applications found in literature. This approach allows readers to quickly identify relevant applications in the tables and refer to the detailed summaries for deeper insights into their methodologies and findings.

4.1. Attribute Tables and Summaries Description

Attribute Tables systematically illustrate each application according to key characteristics, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of the overall approach:

- Ref.: contains the reference application is listed in the first column;

- Year: contains the publication year for each research application;

- Method: contains the specific RL algorithmic methodology applied in each application;

- Agent: contains the agent type of the concerned methodology (single-agent or multi-agent RL approach);

- Baseline: illustrates the comparison methods used to evaluate the proposed RL approach, such as fixed-time (FT), actuated control (AC), max-pressure (MP), CoLight (CL), PressLight (PL), MetaLight (ML), FRAP, SOTL, or other RL-based strategies;

- City Network: contains the main urban traffic network or city where simulations were conducted; each country is abbreviated in parentheses, while simulated traffic networks that do not correspond to a specific city are abbreviated as “synthetic”;

- Junctions: illustrates the number of intersections involved in the study (if multiple scenarios or city networks were evaluated, values for different networks are separated by a “/”);

- Simulation: illustrates the traffic simulation platform used to test and validate the RL method, such as SUMO, VISSIM, Aimsun, CityLearn, or others;

- Data: describes the utilized data that the RL algorithms were trained, tested, and validate on: real data from actual traffic networks are denoted as “real”, simulated and synthetic data as “sim”, and cases where both types of data were utilized are denoted as “both”;

- Cit.: the number of citations—according to Scopus—of each research application.

Moreover, Summaries that following each Attribute Table concern a brief description of the concerned application:

- Author: contains the name of the author along with the reference application;

- Summary: contains a brief description of the research work;

The abbreviations “-” or “N/A” represent the “not identified” elements in tables and figures.

4.2. Value-Based RL Applications

The value-based RL applications for TSC and their primary attributes are integrated in Table 2, while the brief summaries of the applications are illustrated in Table 3:

Table 2.

Value-based RL applications and their basic attributes.

Table 3.

Summaries of value-based RL applications for traffic signal control.

4.3. Policy-Based RL Applications

The policy-based RL applications for TSC and their primary attributes are integrated in Table 4, while brief summaries of the applications are illustrated in Table 5:

Table 4.

Policy-based RL applications and their basic attributes.

Table 5.

Summaries of policy-based RL applications for traffic signal control.

4.4. Actor-Critic RL Applications

The actor-critic RL applications for TSC and their primary attributes are integrated in Table 6, while the brief summaries of the applications are illustrated in Table 7:

Table 6.

Actor-critic RL applications and their basic attributes.

Table 7.

Summaries of actor-critic RL applications for traffic signal control.

4.5. Hybrid RL Applications

The Hybrid RL applications for TSC and their primary attributes are integrated in Table 8, while brief summaries of the applications are illustrated in Table 9:

Table 8.

Hybrid RL applications and their basic attributes.

Table 9.

Summaries of hybrid RL applications for traffic signal control.

5. Evaluation

To offer a structured and comparative overview of existing RL solutions for RES-integrated BEMS, the evaluation focuses on seven key attributes:

- Methodology and Type: Defines the core structure and features of each RL algorithm.

- Agent Architectures: Explores prevailing agent architectures, emphasizing multi-agent RL trends.

- Reward Functions: Analyzes reward design variations across implementations.

- Performance Indexes: Identifies commonly used evaluation metrics and their characteristics.

- Baseline Control Types: Reviews baseline strategies used to benchmark RL performance.

- Intersection Sizes: Assesses intersection modeling complexity, revealing scalability challenges.

- Simulation Tools: Lists the platforms used for simulating RL-based traffic control.

These dimensions capture the critical factors in designing, deploying, and benchmarking RL-based controllers. Dissecting the literature along these axes helps readers understand how RL techniques align with various traffic control frameworks, design constraints, and performance objectives—supporting informed choices for different network scenarios.

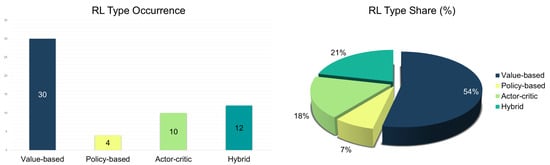

5.1. Methodologies and Types

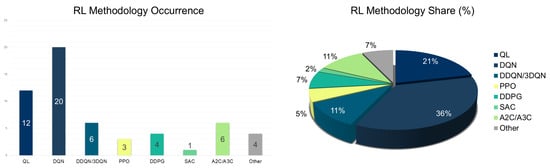

Value-Based: Value-based methods dominate the RL landscape for TSC (see Figure 5, left and right), with QL and DQN widely applied—DQN being the most prominent (Figure 6, left and right). QL is favored for its simplicity in discrete state-action spaces, while DQN extends capabilities to high-dimensional environments via deep function approximation. The evolution of RL methods is marked by a shift from basic QL to advanced DQN variants such as DDQN, dueling DQN, and hierarchical multi-agent frameworks. This transition reflects the need for richer state representations and improved scalability [108,111]. Early studies focused on single intersections or agents [103,107], while more recent efforts explore multi-agent systems and hierarchical coordination [105,128]. These decentralized frameworks enable scalable and synchronized control across complex networks.

Figure 5.

RL types occurrence (left) and share (%) (right) for traffic signal control.

Figure 6.

RL methodologies occurrence (left) and share (%) (right) for traffic signal control.

Another key trend is the integration of domain-specific modeling, including connected vehicle (CV) data [106], partial observability [110], and explicit safety constraints [117,129]. Advances in graph-based neural networks and spatial feature extraction [104,121] further enable adaptive policies that account for topology and vehicle dynamics. Meta-learning approaches [112], non-stationary adaptation [114], and multi-objective optimization (e.g., emissions, safety, equity) [132] signal a more holistic view of urban mobility. Additionally, work on edge computing [111] and new sensor modalities [131] reflects the push toward real-world deployment. These developments collectively indicate a mature field evolving methodologically and operationally.

Policy-Based: Initial efforts, such as [133], leveraged convolutional networks, showcasing stable policy optimization without value estimation. Later work utilized image-based inputs [134], attention mechanisms [135], and CAV coordination [136], expanding the method’s applicability. Despite these advances, however, policy-based RL remains less prevalent due to high sample complexity and training variance. Its strength in continuous action control contrasts with its limitations in discrete settings, where value-based methods are more efficient. Nonetheless, newer strategies incorporating attention and actor-critic frameworks are addressing these challenges by improving sample efficiency and robustness.

Actor-Critic: Such combined methods have progressed from simple continuous-state applications [137] to complex multi-agent frameworks using policy sharing and advanced networks. MA2C models [138] introduced decentralized learning, while improvements like neighborhood fingerprinting and spatial discounting enhanced coordination [139,143]. DDPG architectures [140] employ global critics and local actors to balance centralized training with decentralized control. Recent innovations include LSTM-based estimators for CAV–human synergy [141], graph neural networks for inductive spatial features [142], and asymmetric designs for partial CV data [145]. Actor–critic models have also been adapted to safety-critical tasks, such as emergency vehicle prioritization [146], reinforcing their versatility in diverse traffic scenarios.

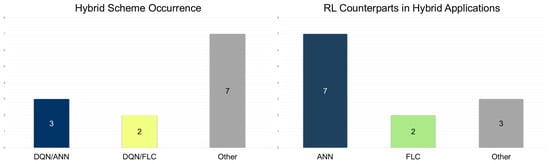

Hybrids: Hybrid RL combines multiple learning strategies and external frameworks (e.g., fuzzy logic, immune networks) to tackle complex traffic objectives. Early approaches integrated RL with immune learning [147], while others adopted fuzzy logic for adaptive reward tuning [152,157]. Hierarchical and layered architectures now blend DQN and PPO modules [151,154], often using deep models like GATs [148,153] and LSTMs [150]. Hybrid frameworks increasingly feature meta-learning and graph-based reasoning [156], with centralized critics and knowledge-sharing mechanisms [149,158] enhancing coordination. Model-based modules [155] have been also integrated to reduce learning time and improve policy performance. Among hybrid approaches, DQN–ANN combinations represent the most common hybrid scheme [148,149,153], followed by DQN–FLC methods [152,157] (see Figure 7, left). ANN-based hybrids—particularly those using LSTM [149,150,156] and GAT [148,153,156,158]—dominate, while FLC remains a competitive alternative (see Figure 7, right).

Figure 7.

Hybrid scheme occurrence (left) and algorithmic counterparts (%) (right) in hybrid RL applications.

Future developments will likely include meta-learning for faster adaptation, transfer learning for model reuse, and expanded integration with V2X, pedestrian detection, and multimodal transport systems. These trends will drive RL solutions to optimize safety, emissions, travel time, and equity. Finally, advances in sim-to-real transfer, edge deployment, and explainable RL will accelerate the adoption of adaptive, data-driven urban traffic control at the city scale.

5.2. Agent Architectures

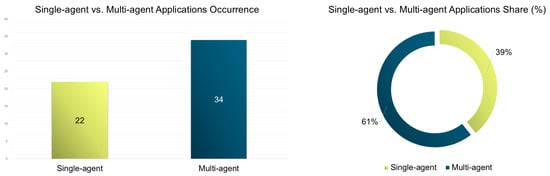

Multi-agent RL (MARL) approaches clearly dominate the traffic signal control literature, particularly throughout the 2015–2025 period. Over 60% of studies utilize MARL methods for managing complex intersection scenarios (see Figure 8, left and right). This trend reflects a shift toward more realistic, large-scale applications. Technological advances in parallel computing, distributed systems, and the availability of open-source traffic simulators—such as SUMO and CityFlow—have significantly enabled scalable, decentralized MARL designs for urban traffic networks [111,119,120,146,148,155].

Figure 8.

Multi-agent vs. single-agent RL applications occurrence (left) and share (%) (right) for traffic signal control via reinforcement learning.

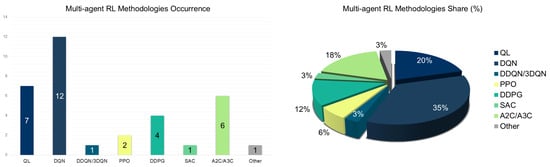

As Figure 9 (left and right) illustrates, value-based methods are the most prevalent MARL frameworks. MARL–DQN is particularly dominant, with numerous studies applying DQNs for decentralized optimization across intersection networks [113,119,120,123,124,130,145,147,149,156]. These approaches demonstrate high scalability and robustness, especially when combined with local observations and experience replay. Classical MARL QL remains relevant [105,106,149,154], particularly in grid-based or hierarchical settings where simpler Q-value models suffice. More advanced versions like DDQN and 3DQN, though promising, are underexplored, with limited implementations showing potential to stabilize learning in high-dimensional settings [119,124]. On the actor-critic front, A2C and A3C models appear most frequently [121,142,144,151,153], using policy-gradient methods and entropy regularization to support distributed behaviors. DDPG-based systems [136,139,140] also show promise, enabling continuous control and precise signal adjustments. However, their adoption is limited by challenges in reward design and instability under partial observability (see Figure 9, left and right).

Figure 9.

Multi-agent RL methodologies occurrence (left) and share (%) (right) for traffic signal control.

The comprehensive analysis of the reviewed studies reveals that, to date, no multi-agent traffic signal control application has been deployed in real-world environments. Even though MARL-based methods have become increasingly sophisticated and show great promise in simulations, bringing them into real-world operation remains a major challenge. A big part of the difficulty comes from the fact that traffic patterns vary greatly between different real-life traffic networks, making it hard to create models that generalize well. Building reliable, fast, and secure communication networks concerns another major hurdle, and even when strong simulation results exist, transferring those models to the messy, unpredictable real world is far from straightforward. Coordination between agents also becomes much harder taking into account real-world issues like communication delays, partial views of the environment, and the unpredictable behavior of human drivers—factors that simulations often oversimplify or overlook. On top of that, problems like scaling up to bigger real-life networks, dealing with unexpected traffic events, ensuring communication standards, and meeting regulatory and safety requirements all add more layers of complexity. Inevitably, overcoming such challenges will be essential to transition from promising research prototypes to fully operational smart traffic systems.

5.3. Reward Functions

In RL-based traffic signal control, the reward function defines the optimization objectives by assigning feedback based on each action’s performance. The reward design plays a crucial role in guiding the agent’s behavior—well-aligned functions promote effective traffic management, while poorly constructed ones can hinder learning or lead to undesirable outcomes. Based on our evaluation, reward functions in TSC fall into six primary categories:

- Queue/Waiting-Time-Based: Such functions measure and penalize vehicle queues or total waiting time, offering direct feedback to reduce congestion. This is the most common reward type, due to its simplicity and effectiveness [103,121,143,148,149] (see Figure 10).

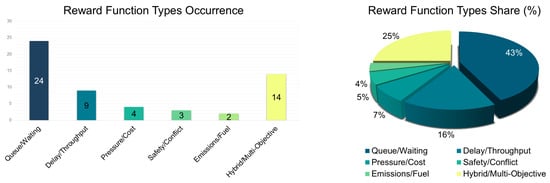

Figure 10. Reward function types occurrence (left) and share (%) (right) for traffic signal control via reinforcement learning.

Figure 10. Reward function types occurrence (left) and share (%) (right) for traffic signal control via reinforcement learning. - Delay/Throughput-Based: These reward structures target average vehicle delay or throughput, encouraging faster clearance and efficient flow. Studies like [105,133,134,135,139,154] apply these to align control with travel time efficiency.

- Pressure/Cost-Based: These rewards assess the difference between inflow and outflow to balance traffic at intersections. By minimizing intersection pressure, they prevent excessive queue buildup [115,136,145,156].

- Safety/Conflict-Focused: These functions penalize potential collisions or unsafe behaviors, promoting safer signal plans. Though less common due to modeling complexity, notable examples include [116,117,129].

- Emissions/Fuel-Centered: These rewards promote eco-efficiency by minimizing fuel use and emissions. Studies like [130,132] integrate such metrics with other objectives to support sustainable traffic control.

- Hybrid/Multi-Objective: These combine several performance indicators—delays, queues, emissions, safety—into a composite reward. Examples include [118,127,155], where fairness, tram priority, and pedestrian flow are jointly optimized.

As illustrated in Figure 10, a large proportion of studies (43%) primarily focus on queue length or waiting time minimization, followed by delay/throughput objectives (16%), and only a small fraction address safety (5%) or environmental impacts (4%). Hybrid or multi-objective reward functions account for 25% of the evaluated studies, reflecting a growing recognition of the need to address the inherently multi-objective, nonlinear, and dynamic nature of real-world TSC systems.

According to the evaluation, a substantial gap remains in systematically balancing efficiency, safety, environmental sustainability, and fairness within RL frameworks. Existing reward designs predominantly focus on optimizing a limited number of objectives, often neglecting others, limiting the robustness and adaptability of learned policies under the variability and uncertainty of real-world traffic conditions. Future research will potentially require the development of hybrid reward functions that integrate multiple heterogeneous performance indicators, where the relative importance of objectives such as delay minimization, collision risk reduction, and emission control may dynamically adapt to varying traffic contexts. Moreover, incorporating constrained reinforcement learning techniques, where safety-critical or environmental thresholds are explicitly embedded within the learning process, could ensure compliance with regulatory or societal requirements even as agents optimize their policies. An additional promising direction involves the application of Pareto-optimal multi-objective learning, enabling agents to discover a spectrum of optimal trade-offs between competing goals without relying on static, hand-crafted weightings. Through these advancements, RL agents could achieve greater generalization and resilience, ultimately making them more applicable to the complex, heterogeneous, and evolving demands of real-world urban traffic management systems.

5.4. Performance Indexes

Performance metrics are used to evaluate how effectively a trained reinforcement learning agent manages traffic signal control. While they may align with the reward function used during training, they often extend beyond it to provide a more comprehensive assessment of the agent’s real-world impact. Common metrics include average travel time, vehicle throughput, stop frequency, and emissions levels. Such indicators help researchers and practitioners compare different approaches, validate generalizations, and ensure that the learned policies meet broader traffic management objectives.

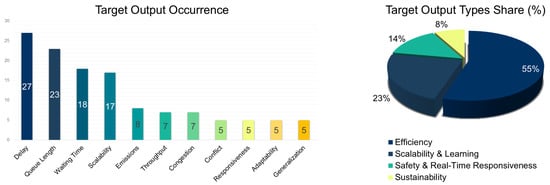

Based on the collective analysis of value-based, policy-based, actor-critic, and hybrid RL methodologies for traffic signal control, the most prevalent target outputs relate to travel time/delay reduction, queue length reduction, waiting time reduction, scalability to large networks, and emission reduction (see Figure 11, left). Travel time and delay reduction emerged as the most dominant performance indicator across all RL types, demonstrating its central role in evaluating TSC efficiency. Numerous studies reported impressive improvements, including Aslani et al. [137] (59.2%), Su et al. [146] (23.5%), Oroojlooy et al. [135] (46%), and Xu et al. [151] (up to 20.1%). This trend reflected the field’s focus on enhancing network-level fluidity and commuter experience by minimizing delay under dynamic conditions. Queue length reduction was also a consistent target, especially in value-based and actor-critic methods, emphasizing localized congestion management. Studies such as Chu et al. [138], Damadam et al. [143], and Wang et al. [158] highlighted reductions ranging from 18% to over 40%, illustrating how RL adapts to node-level traffic accumulation and optimizes phase switching accordingly.

Figure 11.

Performance index type occurrence (left) and share (%) (right) for traffic signal control via reinforcement learning.

Waiting time reduction aligns closely with the above metrics but emphasizes user-centric performance. It was commonly optimized in hybrid and actor-critic setups like Kim et al. [149], Guo et al. [141], and Kumar et al. [152], confirming its relevance in enhancing intersection throughput and driver satisfaction, especially under heterogeneous traffic loads. Scalability to large networks surfaced as a vital output, particularly in multi-agent and graph-based methods such as Wei et al. [148] (tested on 196 intersections), Wang et al. [158], and Wu et al. [144]. Such works prove the growing maturity of RL frameworks that can generalize across cities and dynamically coordinate multiple nodes in parallel, a key enabler for real-world deployment. Moreover, emission reduction, while less frequently reported, represents an emerging priority, especially within hybrid systems that integrate sustainability objectives. Significant reductions were achieved by Aslani et al. [137], Aziz et al. [106], and Tunc et al. [157], showcasing RL’s potential in aligning traffic control with environmental policies.

Beyond the core performance indicators, several other target outputs were identified, reflecting more specialized or emerging research interests. These include throughput increase, often used as a complementary metric to assess network capacity improvements [140,141]; crash/conflict reduction, focusing on safety-aware control strategies such as in [117,129]; and training stability or policy learning speed, important in studies seeking real-time deployment or efficient learning in complex environments (e.g., [111,133]). Additionally, outputs like generalization to unseen scenarios and zero-shot transfer [142,158] highlight the growing interest in robust, transferable RL policies. Collectively, these secondary targets underscore the field’s progression toward safe, reliable, and adaptable RL-based traffic control systems.

In summary, the most prevalent target outputs show a clear shift in RL research toward not only improving traffic flow and reducing delays but also scaling solutions to real-world urban systems, enhancing responsiveness, and incorporating sustainability. This trend signals an evolution from early-stage intersection-specific optimization to city-scale, multi-agent coordination frameworks that balance mobility, efficiency, and environmental impact—a direction likely to dominate future research in intelligent transportation systems.

The classification of target outputs into four thematic groups offers a comprehensive view of the evolving research priorities in RL-based TLC (see Figure 11, right). The efficiency-oriented outputs group—comprising travel time/delay reduction, queue length, waiting time, throughput, and green phase optimization—reflects the field’s core mission to enhance traffic flow and intersection performance. The scalability and learning-centric outputs focus on the robustness and deployability of RL models, addressing challenges like large-scale coordination, stable learning, and rapid policy adaptation through metrics such as generalization and policy convergence. The sustainability-oriented outputs, which include emission and fuel consumption reductions, show an emerging environmental consciousness in traffic management, integrating RL with broader climate and energy goals. Lastly, the safety and real-time responsiveness group introduces a human-centric layer, prioritizing crash/conflict reduction, responsiveness to dynamic traffic or emergency events, and overall congestion mitigation—highlighting a shift toward safer, more resilient urban mobility systems.

The grouped target outputs reveal a clear prioritization in RL-based TSC research. Efficiency-oriented goals dominate, highlighting the field’s longstanding emphasis on reducing travel time, delay, and congestion to improve urban mobility. Scalability and learning-centric outputs reflect growing interest in deploying RL methods across large, complex networks while ensuring generalization, stability, and adaptability—key for real-world applicability. Meanwhile, the increasing attention to safety and real-time responsiveness shows a shift toward more human-centric and reactive systems, especially under mixed traffic and emergency scenarios. Finally, the presence of sustainability-oriented outputs, though less frequent, signals an emerging alignment with environmental objectives, marking a multidimensional evolution of RL-TLC research from isolated efficiency gains to broader, integrated smart city priorities.

5.5. Baseline Control Types

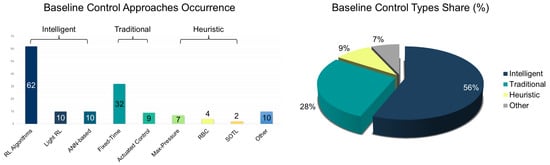

In RL for traffic signal control, baseline methods serve as benchmarks for evaluating proposed RL approaches. These include classical control strategies (e.g., FT, AC), heuristic models (e.g., max-pressure (MP), rule-based control (RBC)), and prior RL-based frameworks. Employing robust baselines is essential for assessing effectiveness, adaptability, and real-world feasibility; thus, evaluations benefit from comparisons across both traditional and state-of-the-art methods.

The current review identifies RL algorithms—such as QL, DQN, A2C, and FRAP—as the most commonly used baselines (see Figure 12, left), reflecting a trend toward benchmarking against advanced RL models rather than solely conventional techniques [108,124]. Light RL frameworks like CoLight, PressLight, and MetaLight, known for integrating graph structures, meta-learning, or pressure logic, are often employed as RL baselines due to their strong performance in multi-agent coordination and generalization [112,148,151]. The inclusion of ANN-based architectures (e.g., GAT, GCN) as baselines further demonstrates the growing relevance of deep representation learning in capturing topological traffic dependencies [115,156]. These intelligent baselines exhibit strong adaptability, real-time decision making, and coordinated control across complex networks (see Figure 12, right). Classical control strategies, including fixed-time and actuated control, remain prevalent baseline choices. FT control, long dominant in urban systems, is favored for its simplicity, reliability, and historical use, serving as a static benchmark [107,127]. AC, by contrast, adjusts signals based on sensor input, offering a middle ground between static and fully adaptive systems [105,116]. Heuristic-based approaches, such as rule-based control (RBC) and max-pressure (MP), offer interpretable, domain-informed logic. MP, in particular, is notable for its decentralized, queue-aware control that performs competitively with modern RL models [142,148]. RBC applies predefined rules without learning, offering simplicity and serving as a stand-in for traffic engineering expertise [109,121]. The self-organizing traffic lights (SOTL) model also appears in this category, using local heuristics—such as vehicle counts or wait thresholds—for decentralized decisions.

Figure 12.

Baseline control types occurrence (left) and share (%) (right) for traffic signal control via reinforcement learning.

Less common baselines include priority-based methods, gap-based logic, and hybrid models like MPC and FLC. Such baselines typically address niche scenarios or integrate expert knowledge into fuzzy logic frameworks [152,155], benchmarking RL agents in tasks requiring nuanced control strategies.

5.6. Intersections Sizes

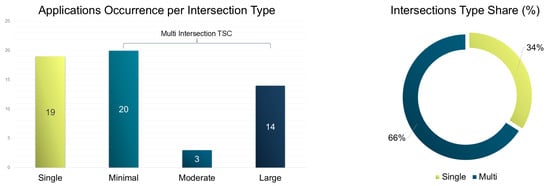

The number of intersections modeled in RL studies directly impacts the computational complexity of the traffic network. As intersection count increases, the problem scales from localized optimization to dynamic, multi-agent coordination—demanding more advanced learning architectures. This review categorizes intersection complexity into four types:

- Single-scale: 1 intersection;

- Minimal-scale: 2–6 intersections;

- Moderate-scale: 7–30 intersections;

- Large-scale: 30+ intersections.

To this end, according to the comprehensive examination of each integrated high-impact research work, Figure 13 (left) shows the distribution of study types, while Figure 13 (right) contrasts single vs. multi-intersection implementations.

Figure 13.

Intersection types occurrence (left) and share (%) (right) for traffic signal control via reinforcement learning.

According to the evaluation, most research remains concentrated on single-scale scenarios (see Figure 13, left and right), where RL models are first tested under controlled conditions. These studies often benchmark against fixed-time or actuated systems. Examples include DQN-based controllers for single intersections [103,107], and fuzzy–DQN hybrids [152], offering enhanced adaptability in real-world settings. Minimal-scale scenarios mark the initial transition toward MARL coordination. These works typically simulate small networks (e.g., 2 × 2 or 2 × 3 grids) to evaluate local cooperation. Nishi et al. [104] used a GCNN-based RL controller across six intersections, while Haddad et al. [124] showed coordination improvements in 2 × 2 and 2 × 3 grids. Moderate-scale studies are significantly less frequent (see Figure 13, left), highlighting a gap in research targeting mid-sized urban networks. Such networks require regional coordination but fall short of city-wide complexity. In [106], RMART was deployed across 18 intersections using neighborhood data sharing. Chu et al. [138] demonstrated MA2C’s performance on a 5 × 5 grid and a real-world 30-intersection network in Monaco. Last but not least, the large-scale studies indicate a growing shift toward city-scale adaptive control. Graph-based RL and hierarchical architectures are key in managing such complexity. For example, in [115], researchers evaluated MPLight on Manhattan’s 2510 intersections, while CoLight [148] achieved a 19.89% travel time reduction across 196 intersections.In [158], researchers introduced a multi-layer graph mask Q-learning system across 45+ intersections, demonstrating scalability and zero-shot generalization.

As Figure 13 (right) illustrates, there is a clear evolution from early single-intersection studies [103,107,152] to scalable, network-level systems. MARL strategies [105,109,138] have facilitated decentralized control, while hybrid RL frameworks [151,158] integrate graph models and hierarchy to enable real-time, city-scale management. The inclusion of IoT data and predictive modules [141,143,154,155] suggests a trend toward adaptive, transferable RL systems for deployment in real-world urban environments.

5.7. Practical Applicability

In the context of RL for traffic signal control, evaluating the practical applicability of each method requires moving beyond algorithmic novelty and considering operational attributes that determine real-world viability. Three pivotal dimensions for such assessment concern the computational efficiency, scalability, and generalization ability of each relevant algorithmic application. Computational efficiency reflects the model’s feasibility for deployment on traffic control hardware and is influenced by neural network size, training convergence speed, and real-time inference potential. Scalability pertains to how well a method adapts to larger, more complex urban networks, often shaped by the agent architecture—e.g., decentralized MARL—and communication overhead. Generalization captures the robustness of the trained policy when exposed to diverse traffic conditions, layouts, or environments from the training scenario—an essential trait for adaptive urban mobility systems.

To enable a meaningful cross-study evaluation, each of the three dimensions—computational efficiency, scalability, and generalization ability—are qualitatively assessed as high, medium, or low based on evidence found in each study. The assignment is grounded in clearly defined criteria derived from reported methodologies, network sizes, architectural choices, and validation protocols. More specifically:

- Computational Efficiency: This reflects both training and inference complexity. A high score concern studies that utilized lightweight models (e.g., shallow networks or simplified tabular Q-learning) and demonstrated fast convergence, often within a few episodes or minutes of simulated time. Such models are typically suitable for real-time deployment or hardware-constrained environments. For example, simple DQN architectures applied to four-phase intersections with prioritized experience replay often fall into this category. A medium score indicates moderate model complexity—such as e.g., deep actor-critic methods—that require longer training times but are still computationally feasible using standard GPUs or cloud-based environments. These may include multi-agent PPO or A3C models applied to mid-sized grids. A low rating is reserved for models involving large neural networks, extensive hyperparameter tuning, or unstable learning dynamics (e.g., convergence issues, reward oscillations). Such models may include, for instance, DDPG-based methods with continuous actions across dozens of agents, which are computationally intensive and often unsuitable for real-time use without high-performance computing infrastructure.

- Scalability: The scalability attribute assesses how well the RL approach extends from small-scale to large-scale or city-wide deployments. A high rating concern RL applications validated on large urban networks—e.g., large-scale networks with 30+ intersections or city-level topologies—often by using decentralized or hierarchical multi-agent structures that minimize communication overhead. Examples include MARL–DQN variants tested on synthetic or real urban networks with asynchronous updates. A medium score is assigned to studies that demonstrated applicability to moderate-scale scenarios, such as 3 × 3 or 5 × 5 intersection grids—typically moderate-scale complexity considering 7–30 intersections—where scalability was addressed but not rigorously tested or discussed. Centralized training with decentralized execution (CTDE) frameworks often fall here. A low score indicates evaluation on isolated intersections or minimal-node networks, without explicit consideration of inter-agent coordination or traffic spill-back effects: single and minimal-scale networks of 1–6 intersections. Such applications tend to lack architectural features or experimental adequacy, necessary for generalizing to larger, more complex road networks.

- Generalization Ability: Generalization measures robustness to unseen traffic scenarios, layouts, or non-stationary environments. A high score applies to RL cases that explicitly evaluate transfer learning, domain randomization, or training under variable traffic demands—indicating adaptability beyond a single training case. Examples include studies using multi-scenario training or that successfully transfer policies to different intersection geometries or demand profiles. The medium rating is for cases where models are trained with minor variations in traffic input or tested on different seed initializations, but without formal generalization analysis. RL methods that utilized fixed synthetic routes or rely on a single SUMO simulation file usually fall into this category. The low rating is for RL applications that have been solely trained and evaluated in static, deterministic settings, with no consideration for transferability, noise resilience, or policy degradation under new conditions.

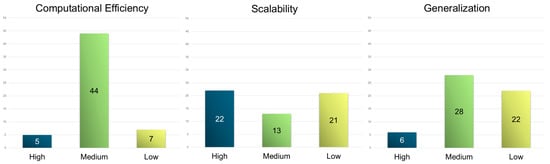

By systematically applying these assessment criteria across the surveyed studies, this subsection aims to highlight not only the algorithmic sophistication but also the operational readiness and deployment potential of each RL approach. Figure 14 shows the number of applications with regards to computational efficiency, scalability, and generalization in high, medium, and low grades as depicted by the examination of the high-impact integrated papers.

Figure 14.

Number of applications with regard to computational efficiency (left), scalability (center), and generalization (right) categorized in high, medium, and low grades.

According to the evaluation, among the integrated studies, only a few achieve high computational efficiency, notably those using tabular or lightweight value-based RL algorithms. For instance, in [106,114,116], researchers leveraged tabular QL or average-reward methods that forgo deep architectures, enabling rapid convergence and real-time deployment. Similarly, in [118,126], researchers achieved high efficiency through simplified double DQN or rule-based models optimized for low-latency environments. In contrast, most medium-rated methods such as in [103,104,112,149], employed moderate DQNs or actor-critic networks that balance learning capacity with hardware feasibility, often using experience replay, shared parameters, or target networks to stabilize learning. Low-computational-efficiency cases such as in [134,139] typically involved deep policy gradient models with LSTM, attention, or graph structures, incurring high training cost, slow convergence, and GPU dependencies that challenge deployment in real-time traffic signal environments.

Scalability emerged as the most successfully achieved attribute, with numerous applications rated as high. Such approaches included hierarchical or decentralized MARL frameworks, often using parameter sharing or communication-efficient strategies. Notably, in [115,121], researchers scaled up to 2510 and 3971 intersections, respectively, by adopting decentralized policies and shared GNN-based representations. Similarly, in refs. [120,142,153], authors demonstrated city-scale control through decentralized agents with limited or implicit coordination, often enhanced with graph attention or localized observations. Architectures like CoLight [148] and CoTV [136] utilized graph-based communication and actor-critic setups to maintain linear scalability without centralized bottlenecks. In contrast, medium-scalability approaches, such as those in [124,125], were validated only on modest-sized grids and lack robust coordination protocols. Low scalability is prevalent in methods focused on single intersections (e.g., [103,157]), which lack multi-agent logic or architecture modularity for broader network control.

Only a limited subset of studies demonstrated high generalization, typically by incorporating transfer learning, meta-learning, or evaluation across unseen environments. MetaLight [112], IG-RL [121], and CVLight [145] exemplify strong generalization by leveraging meta-initialization, inductive GNNs, or policy pre-training across varied traffic scenarios and topologies, achieving robust zero-shot transfer. For instance, both [137,146] approaches similarly integrated dynamic data or function approximation (e.g., RBF networks) to support adaptation across environmental variations. Most medium-rated generalization studies, such as in [107,110,113], were evaluated on synthetic scenarios with some variability in traffic flow or seed, but they lack formal robustness analysis or domain transfer. A significant number of studies, however, fell under low generalization, often training on fixed layouts with static flows and no evaluation on unseen networks (e.g., in [122,149,158]). Such RL applications were highly scenario-dependent, limiting their adaptability to real-world deployment or unexpected traffic conditions.

It is noticeable that only a very small subset of works manage to simultaneously achieve high computational efficiency, scalability, and generalization ability, standing out as exemplary frameworks in the landscape. Notably, the IG–RL model proposed by Devailly et al. [121] integrated a deep graph convolutional network (GCN) with shared parameters and object-level abstraction, allowing for lightweight inference, near-zero-shot transferability, and massive-scale deployment (up to 3971 intersections in Manhattan). Similarly, CVLight by Mo et al. [145] achieved such balance using an asymmetric advantage actor-critic model with pre-training, decentralized control, and communication-free execution. Its design supported real-time operation, generalized across demand levels and CV penetration rates, and scales effortlessly to 5 × 5 grids. The MetaLight framework [112] also demonstrated all three attributes through a meta-learning-based FRAP++ architecture, providing fast adaptation to new environments, structure-agnostic deployment, and efficient training via parameter sharing. These models typically combined: (i) architectural simplicity or modularity (e.g., parameter sharing, decentralized inference); (ii) learning acceleration techniques (e.g., meta-initialization, curriculum learning); and (iii) broad validation across synthetic and real-world conditions to achieve high grade in all three attributes.

Inevitably, the path forward for RL-based traffic signal control research lies in jointly optimizing computational efficiency, scalability, and generalization ability—a triad essential for real-world deployment. Future systems should favor modular architectures with shared policies or decentralized agents that minimize inter-agent communication but support coordination (e.g., via attention or graph representations). Meta-learning, domain randomization, and transfer learning should be standard components in training pipelines to ensure robustness across diverse traffic scenarios and topologies. Importantly, computational parsimony must not be sacrificed for complexity: lightweight DQN variants or actor-critic methods with optimized network depth may achieve competitive results if well structured. Research should also embrace cross-domain benchmarks, testbeds with variable layouts, and real-world data (e.g., LuST, OpenStreetMap imports) to stress-test generalization. Promoting such attributes mutually may prove beneficial to ensure that RL-TSC systems transition from academic proofs-of-concept to scalable, reliable, and adaptive traffic control platforms in smart cities.

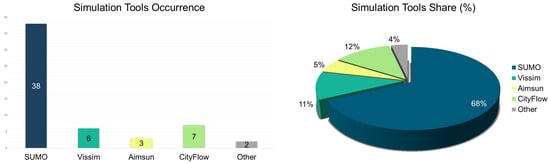

5.8. Simulation Tools

Researchers applying RL to traffic signal control rely on flexible, high-fidelity simulation environments to rigorously test and benchmark algorithms prior to real-world deployment. These tools enable the creation of detailed urban traffic networks, definition of diverse traffic patterns, and incorporation of realistic driver behavior and vehicle heterogeneity. They also allow adjustments to road layout, signal timing, and traffic volume, supporting controlled experimentation and reproducibility. Importantly, most offer APIs or scripting tools for seamless RL integration. According to the evaluation, the primary simulation platforms used in RL-based traffic signal control research include:

- SUMO: A widely adopted open-source, microscopic, multi-modal traffic simulator offering scalability, adaptability, and robust modeling capabilities (e.g., lane changing, multi-lane configurations, emissions analysis) [159]. SUMO’s modular structure and tools (e.g., netconvert, duarouter) streamline network preparation and traffic scenario simulation, making it ideal for RL-based signal control studies.

- Vissim: A commercial, high-resolution traffic simulation platform from PTV Group [160]. Known for accurate multimodal traffic modeling, advanced driver behavior algorithms, and scenario management, Vissim is suited for evaluating transport infrastructure and integrating RL-based control with high realism.

- Aimsun: A commercial predictive traffic analytics platform supporting adaptive control and intelligent transportation systems (ITS) [161]. Aimsun enables performance assessment, network evolution forecasting, and real-time optimization, making it suitable for RL applications in large-scale digital mobility solutions.

- CityFlow: An open-source, high-performance traffic simulator designed for scalability in RL-based traffic control [162]. CityFlow features optimized data structures and algorithms for city-wide simulations, outperforming SUMO in speed while supporting flexible configurations and seamless RL integration [162].

- Other: A limited number of studies employed alternative simulators. For instance, in [103], researchers used Paramics [163], known for detailed micro-simulations and behavior modeling. Meanwhile, in [134] they used a Unity3D-based custom simulator [164], offering scenario flexibility for advanced sensor integration and agent modeling.

Overall, simulator choice depends on factors such as budget, fidelity requirements, integration ease, and project scale. According to the review, SUMO remained the most frequently used platform between 2015 and 2025 (See Figure 15). Its open-source license, robust community support, scalable architecture, and Python 3.6 TraCI interface make it ideal for RL experimentation, especially in academic and collaborative contexts. SUMO’s scripting capabilities allow rapid prototyping of diverse algorithms for adaptive traffic control. Commercial tools like Vissim and Aimsun continue to support high-fidelity modeling and seamless ITS integration. Their use in studies such as [106,114,116,127,141,147] for Vissim and [117,137,154] for Aimsun demonstrate their utility in advanced traffic signal control scenarios. CityFlow has gained traction as a lightweight yet powerful open-source simulator tailored for large-scale MARL applications. Studies such as [112,115,135,144,148,151,156] utilize CityFlow to simulate city-wide coordination tasks efficiently, reflecting its rising role in enabling real-time, scalable, RL-based urban traffic control.

Figure 15.

Simulation tools occurrence (left) and share (%) (right) for traffic signal control via reinforcement learning.

6. Discussion

This section is structured into three parts, Current Trends, Identified Challenges, and Future Directions, offering a clear synthesis of the review’s findings and their broader implications. The Current Trends subsection is grounded on the evaluation section observations and outlines dominant patterns and recurring strategies in RL-based traffic signal control (TSC), while the Challenges Identification subsection highlights the open challenges and unexplored opportunities for advancing both theoretical research and practical implementation. The Future Directions subsection concerns future research needs that focus on specific areas to effectively address the challenges and identified limitations in order to enhance the real-world applicability of RL in TSC.

6.1. Current Trends

- ✓

- Dominance of Value-Based RL: Value-based methods, particularly DQN and its variants, remain the most widely used due to their alignment with the discrete nature of traffic signal phases and their stable convergence properties [108,111,113,124]. Their origins in game-based RL tasks made them well-suited for modeling discrete decisions like phase switching, supporting simplified policy updates and lower training overhead [103,107,128]. Enhancements like double and dueling DQN address overestimation and feature learning, improving the capture of spatiotemporal traffic patterns [119,128].

- ✓

- Growing Adoption of Hybrid and Domain-Specific Techniques: A marked shift toward combining RL paradigms—value-based, policy-based, fuzzy logic, and MPC—has emerged to better handle real-world traffic complexities [147,152,154,157]. These hybrids leverage complementary strengths such as fuzzy logic’s interpretability or model-based components’ predictive accuracy. Embedding domain-specific priors (e.g., road topology, priority rules) helps align RL with engineering logic and enhances performance in dynamic settings [145,155].

- ✓

- Advanced Neural Modules as Key Enablers: Neural enhancements like GNNs, attention mechanisms, and temporal encoders (e.g., LSTMs) have been instrumental in capturing spatial and temporal dependencies in multi-intersection networks [104,121,148]. GNNs facilitate inter-agent communication through relational state embeddings, while attention layers highlight critical lanes or intersections within complex urban grids [135,136,145].

- ✓

- Prevalence of Multi-Agent Architectures: The decentralized nature of urban traffic has driven widespread adoption of multi-agent RL [120,149]. Treating each intersection as an agent allows localized decision making with shared coordination logic via mechanisms such as neighborhood masking and graph-based message passing, enabling scale-out from grids to entire cities [105,119].

- ✓

- Reliance on Classic Traffic Metrics: Most studies anchor their reward functions to traditional indicators like waiting time, queue length, or average delay [103,133]. These metrics offer a clear bridge to conventional traffic management practices, facilitating both validation and interpretability in comparative analysis [107,135].

- ✓

- Emergence of Broader Objectives in Reward Design: Recent works have expanded RL goals to include emissions, safety, and equity, pushing beyond congestion alone [117,129,132]. These additions demand nuanced reward formulations that balance multiple, often competing, performance criteria [130,136].

- ✓

- Algorithm Choice Driven by Objective Complexity, Not Scale: The selected RL framework often correlates more with task complexity (e.g., safety, sustainability) than with network size [114,145]. Sophisticated methods appear even in single-intersection studies, while simpler techniques persist in large-scale scenarios when congestion is the primary concern [136,158].

- ✓

- Blurring of Discrete and Continuous Control Paradigms: While traffic signals operate on discrete cycles, researchers increasingly employ continuous action spaces through actor-critic architectures, enhancing the granularity of phase control and reducing abrupt transitions [137,140,145].

- ✓

- Benchmarking Against Classical and RL Baselines: Iterative benchmarking—against fixed-time, actuated, or prior RL models (e.g., CoLight, PressLight)—remains standard practice, promoting consistency and cumulative progress in the field [108,148].

- ✓

- Scalability and Real-World Relevance: An increasing number of studies target multi-intersection or city-scale deployments using advanced modules like GNNs and hierarchical decomposition, aligning academic research with real-world deployment challenges [115,121,156].

- ✓

- SUMO as the Dominant Simulation Platform: SUMO’s open-source nature, modularity, and Python API (TraCI) have made it the preferred tool for RL-TSC experimentation [115,159]. Its adaptability supports complex network modeling, while its ecosystem promotes replicability across institutions [106,119].

6.2. Challenge Identification

Challenges in current RL implementations for traffic signal control remain significant despite considerable advancements. Some challenges stem directly from algorithmic complexity and control design, while others relate to practical issues, prohibiting the real-world deployment of RL in traffic signal control. More Specifically:

- ■