Conflict Risk Assessment Between Pedestrians and Right-Turn Vehicles: A Trajectory-Based Analysis of Front and Rear Wheel Dynamics

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Novel Vehicle Trajectory Modeling. The paper introduces a front-and-rear-wheel trajectory (FRWT) framework for R-T vehicles, addressing the limitation of centroid-point simplification in existing studies. It partitions vehicles into four segments (inner/outer front/rear wheels) to analyze risk disparities across different vehicle parts. And it proposes a geometric mathematical model of the trajectories of right-turning vehicles. This allows the prediction of the inner front and rear wheel trajectories of R-T vehicles at intersections and provides a foundation for conflict risk assessment based on the FRWT method for R-T vehicles.

- (2)

- Identification of High-Risk Conflict Zones. It demonstrates that the inner front wheel poses the highest collision risk due to its speed, trajectory curvature, and proximity to pedestrians, followed by the inner rear, outer front, and outer rear wheels.

- (3)

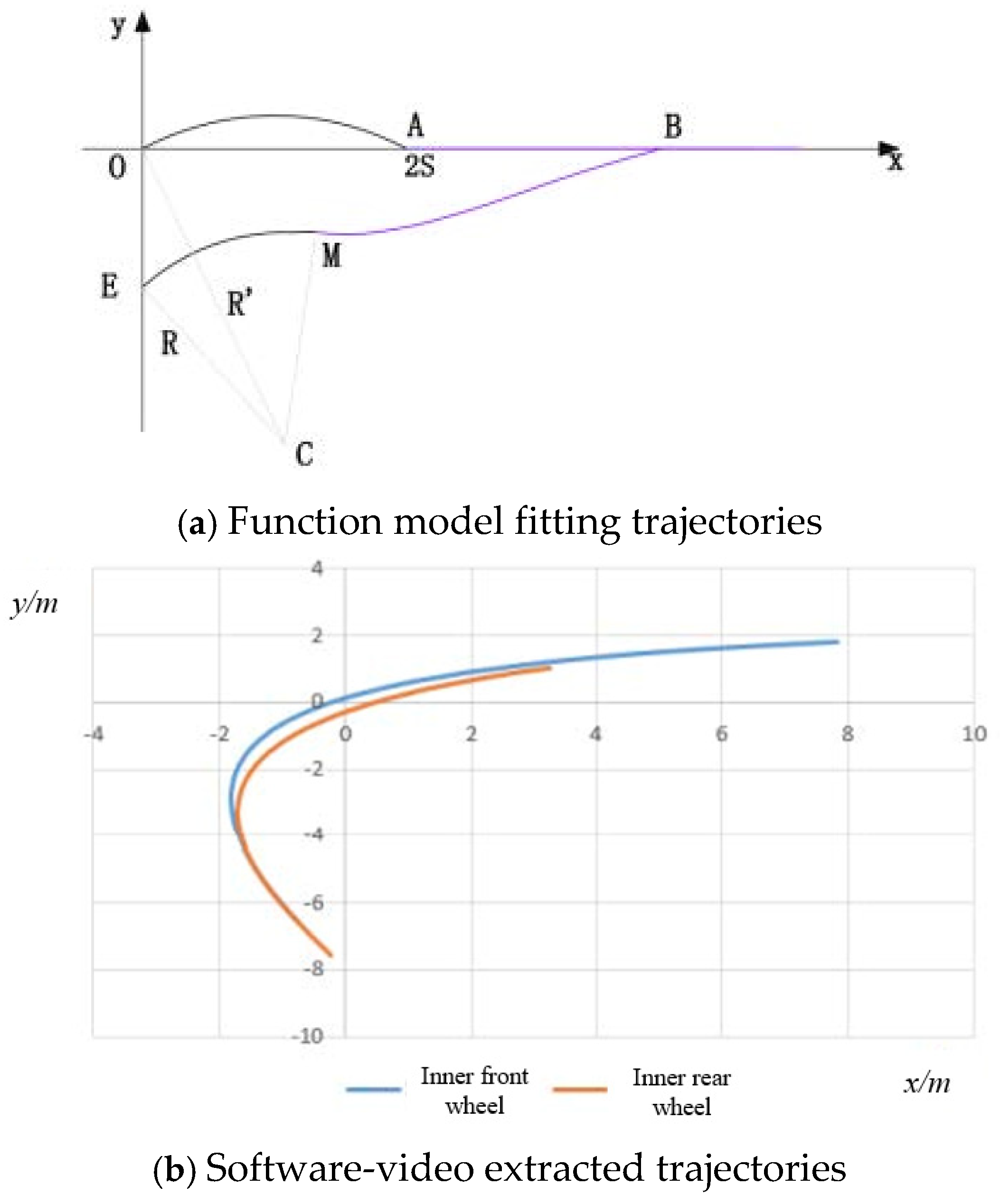

- Trajectory Prediction Model. It develops a mathematical model for R-T vehicle trajectories, validated against real-world video-extracted data, showing strong alignment with observed wheel paths.

- (4)

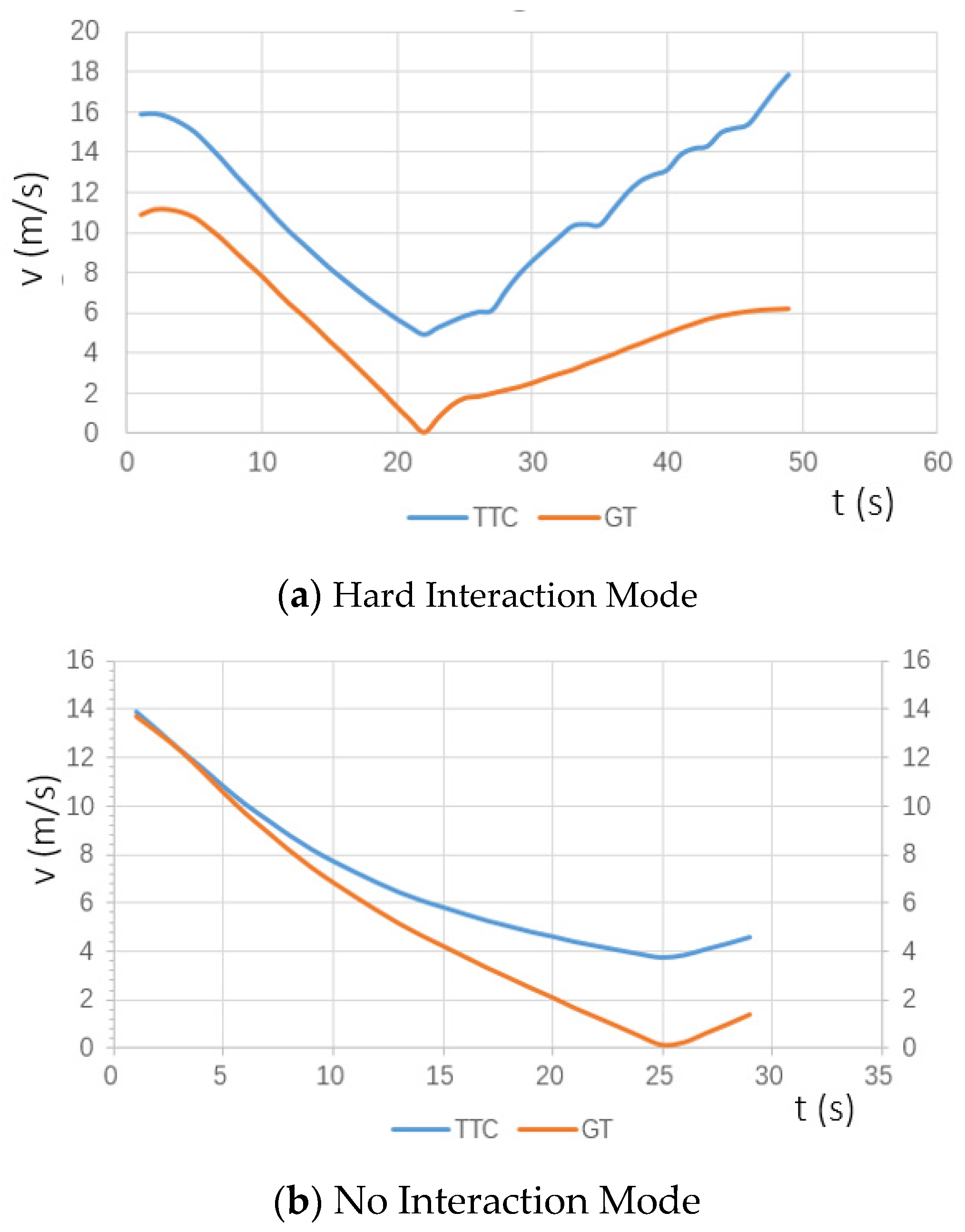

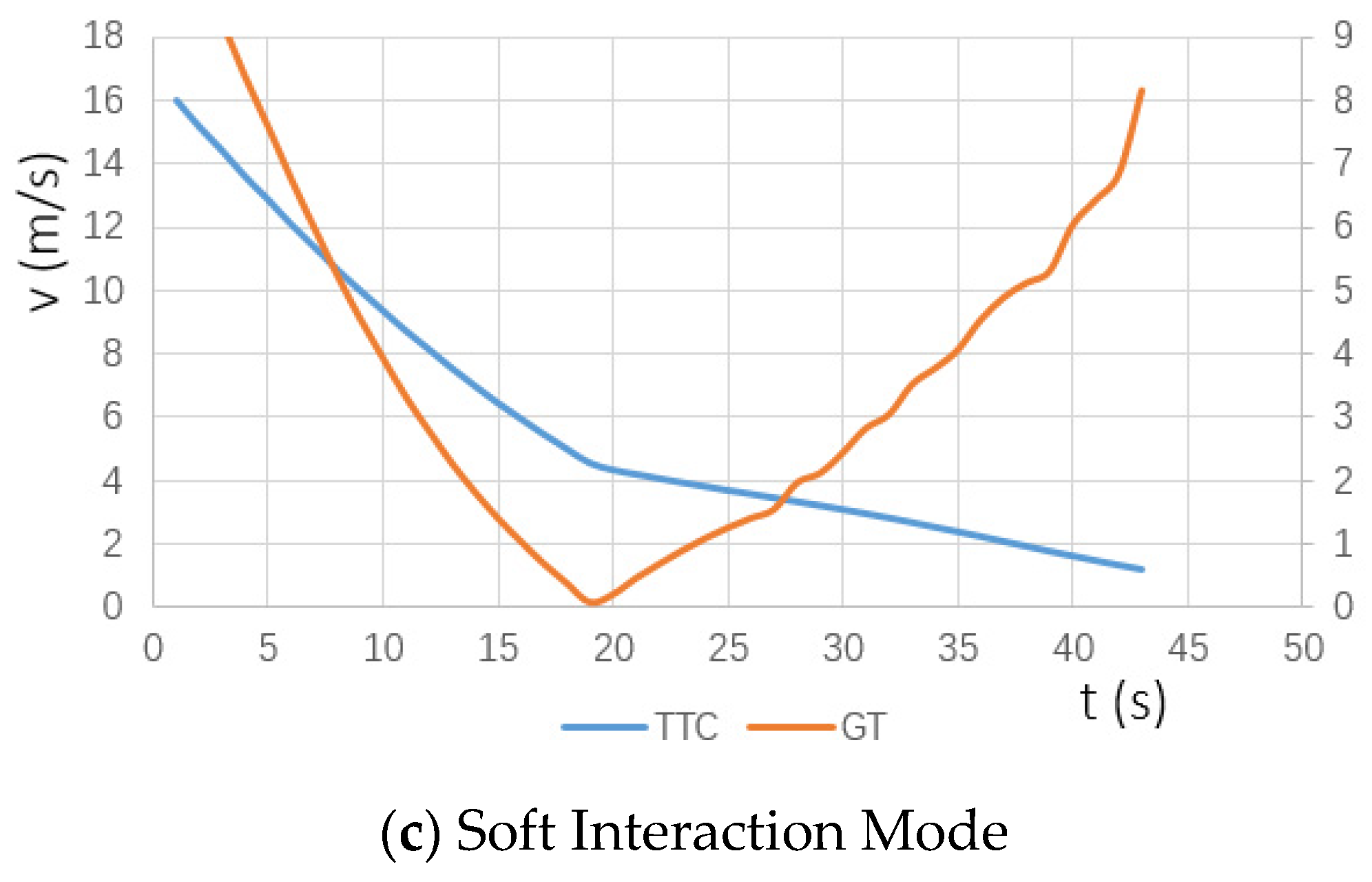

- Classification of Interaction Modes and Conflicts. It proposes three pedestrian–vehicle interaction modes (hard interaction, no interaction, soft interaction) based on trends in Time to Collision (TTC) and Gap Time (GT) curves. Additionally, it employs Support Vector Machine (SVM) with k-fold cross-validation to classify conflict severity levels, outperforming single-indicator methods.

- (5)

- Practical Implications for Safety Management. It provides a data-driven framework for proactive safety interventions at RTOR intersections, enabling targeted mitigation strategies (e.g., redesigning high-risk wheel-path zones).

2. Literature Review

2.1. Vehicle Trajectory Extraction Method

2.2. Pedestrian–Right-Turn Vehicle Conflict Risk Evaluation

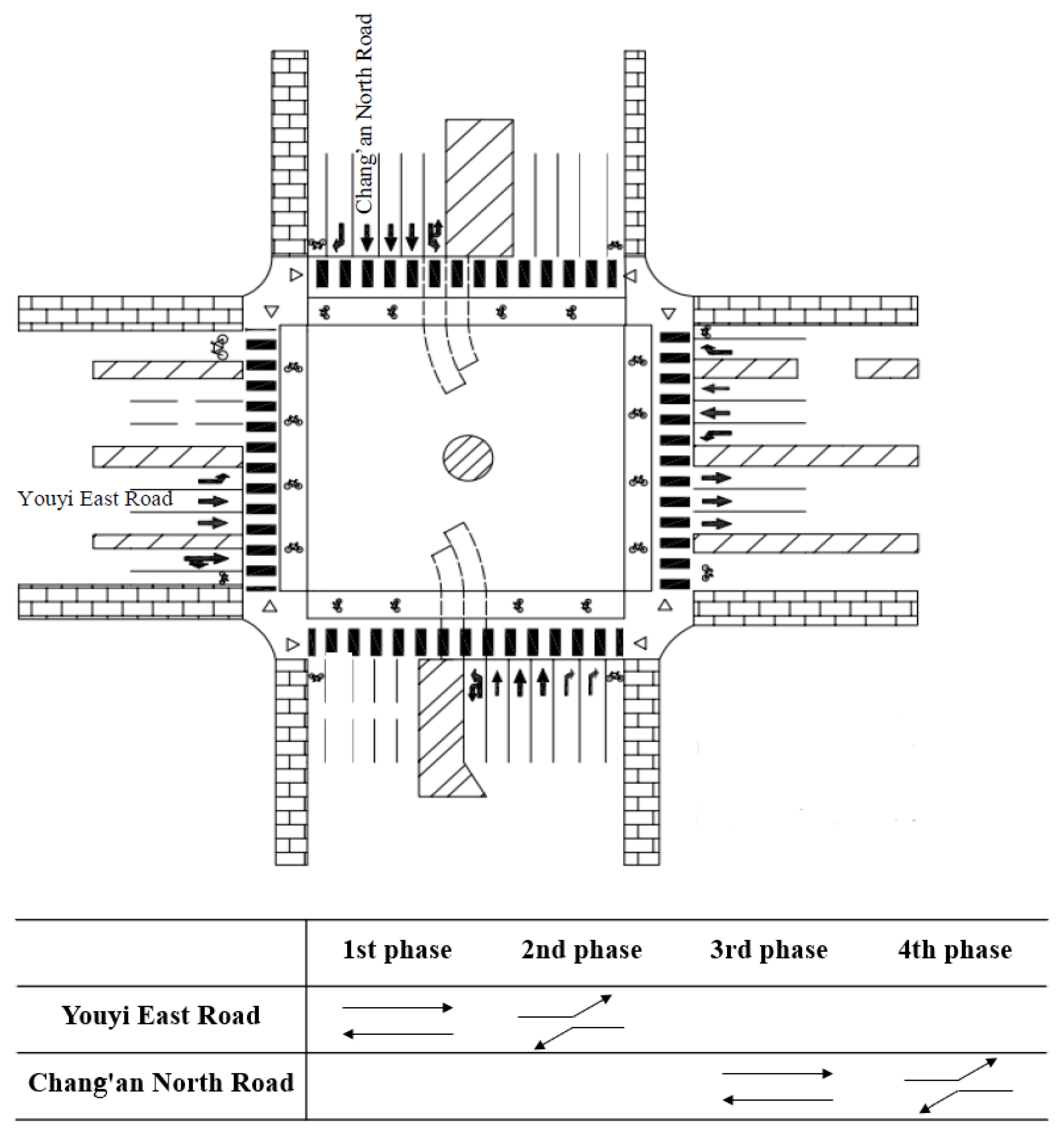

3. Data Acquisition and Analysis

3.1. Vehicle Unit Data

3.1.1. Front and Rear Wheel Trajectory Division

3.1.2. Vehicle Physical Structure Division

3.2. Right-Turn Vehicle Trajectory Data

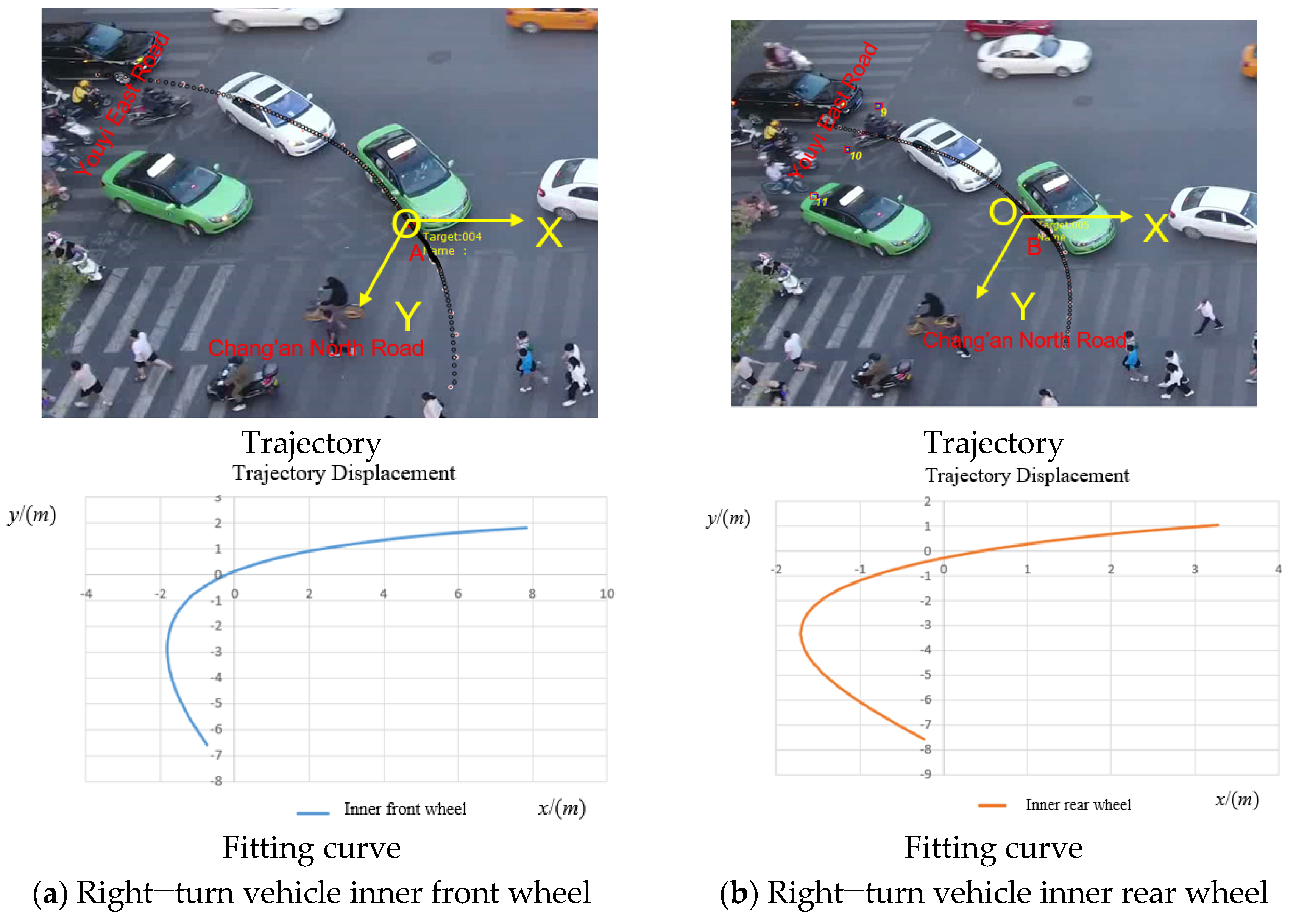

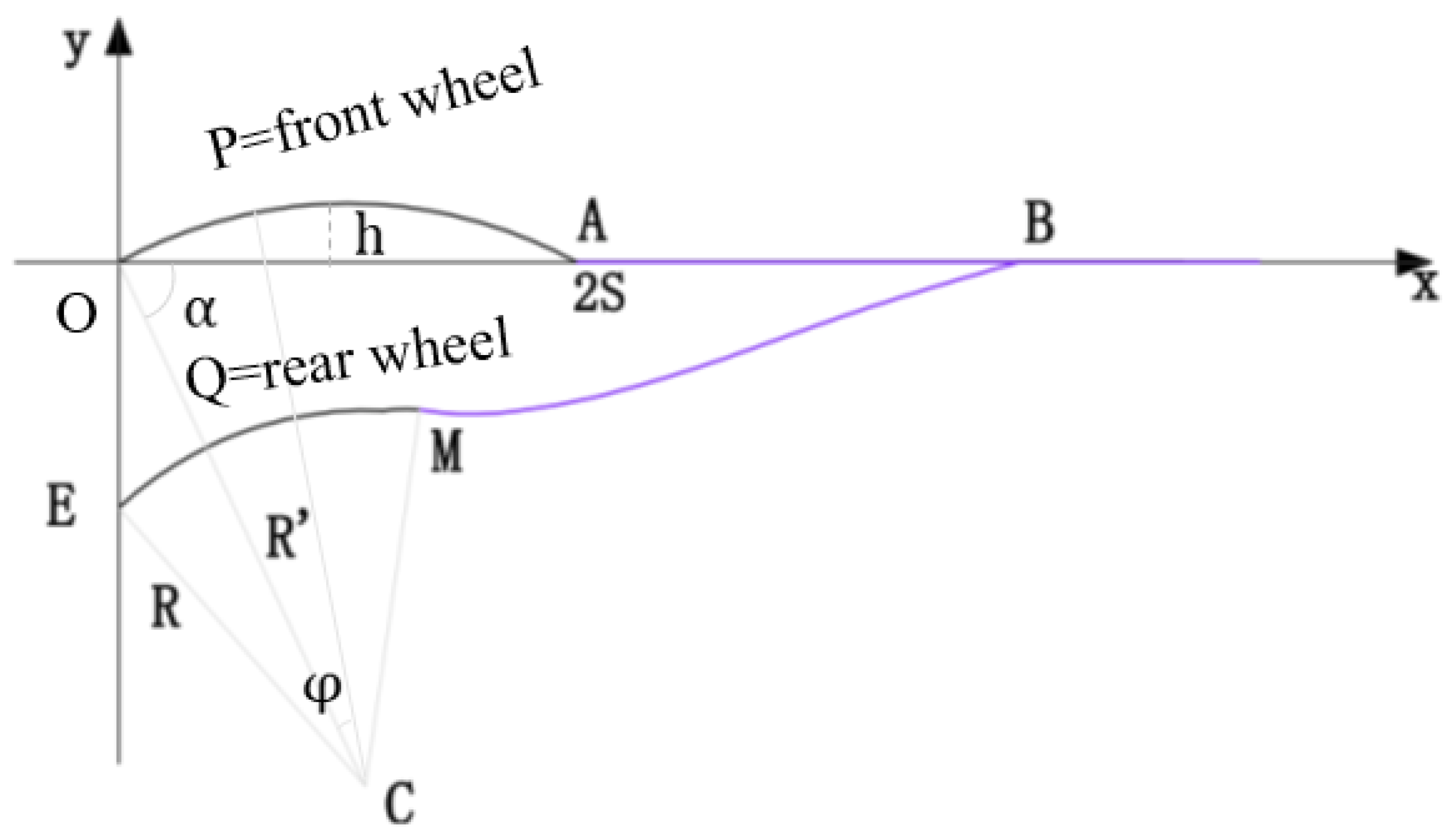

3.2.1. Inner Wheel Trajectory Extraction

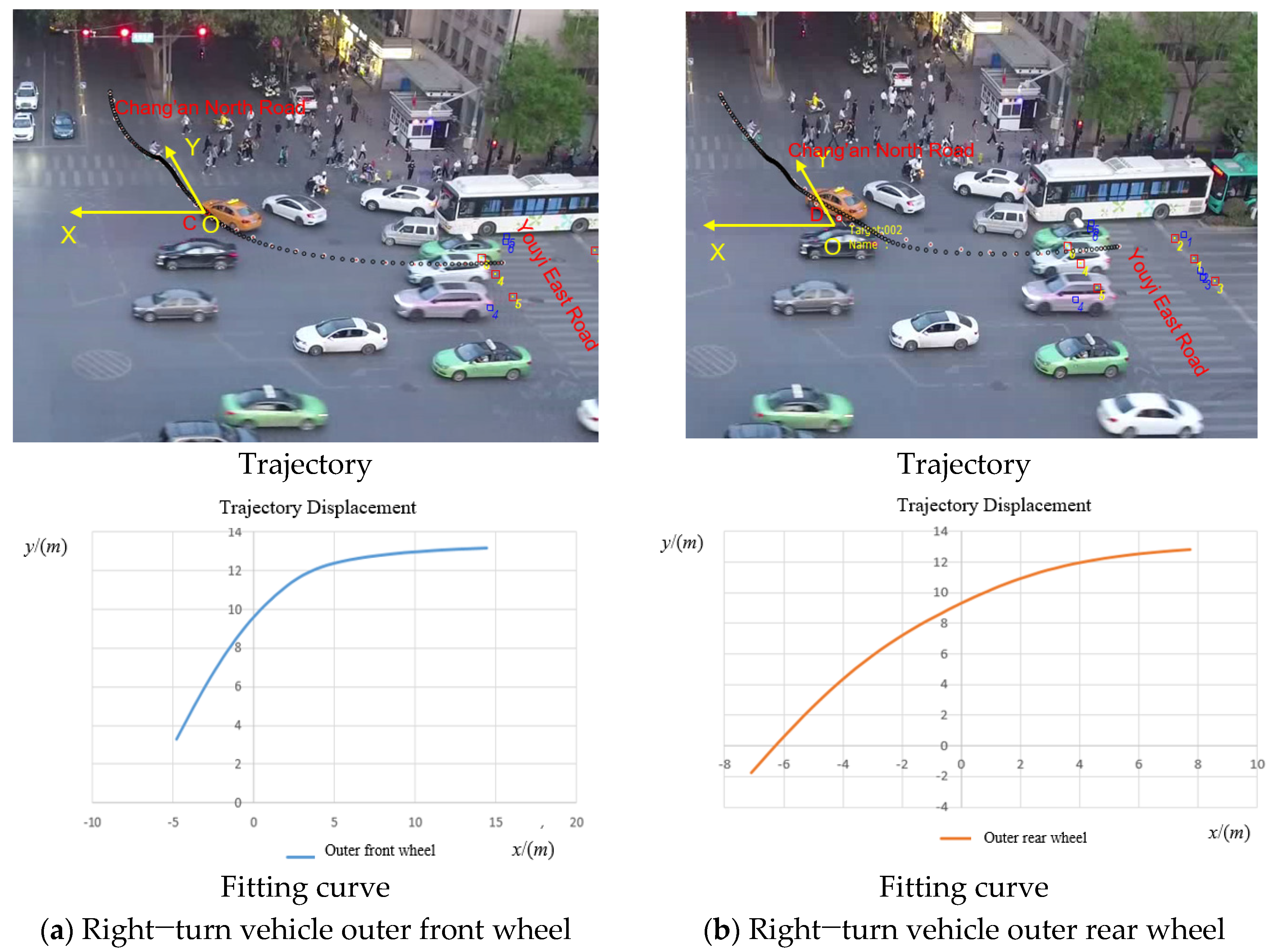

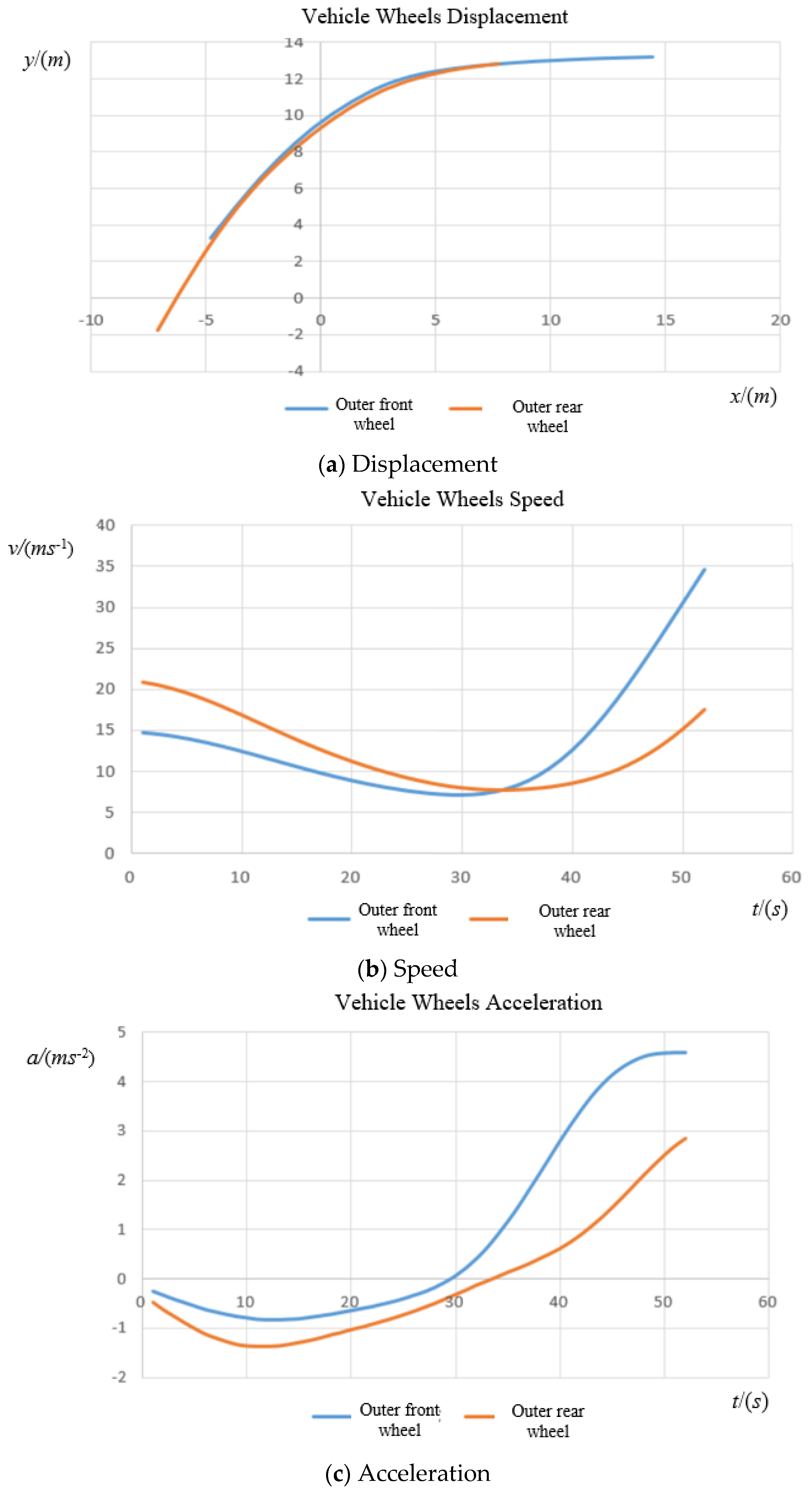

3.2.2. Outer Wheel Trajectory Extraction

3.3. FRWT Risk Differences Analysis

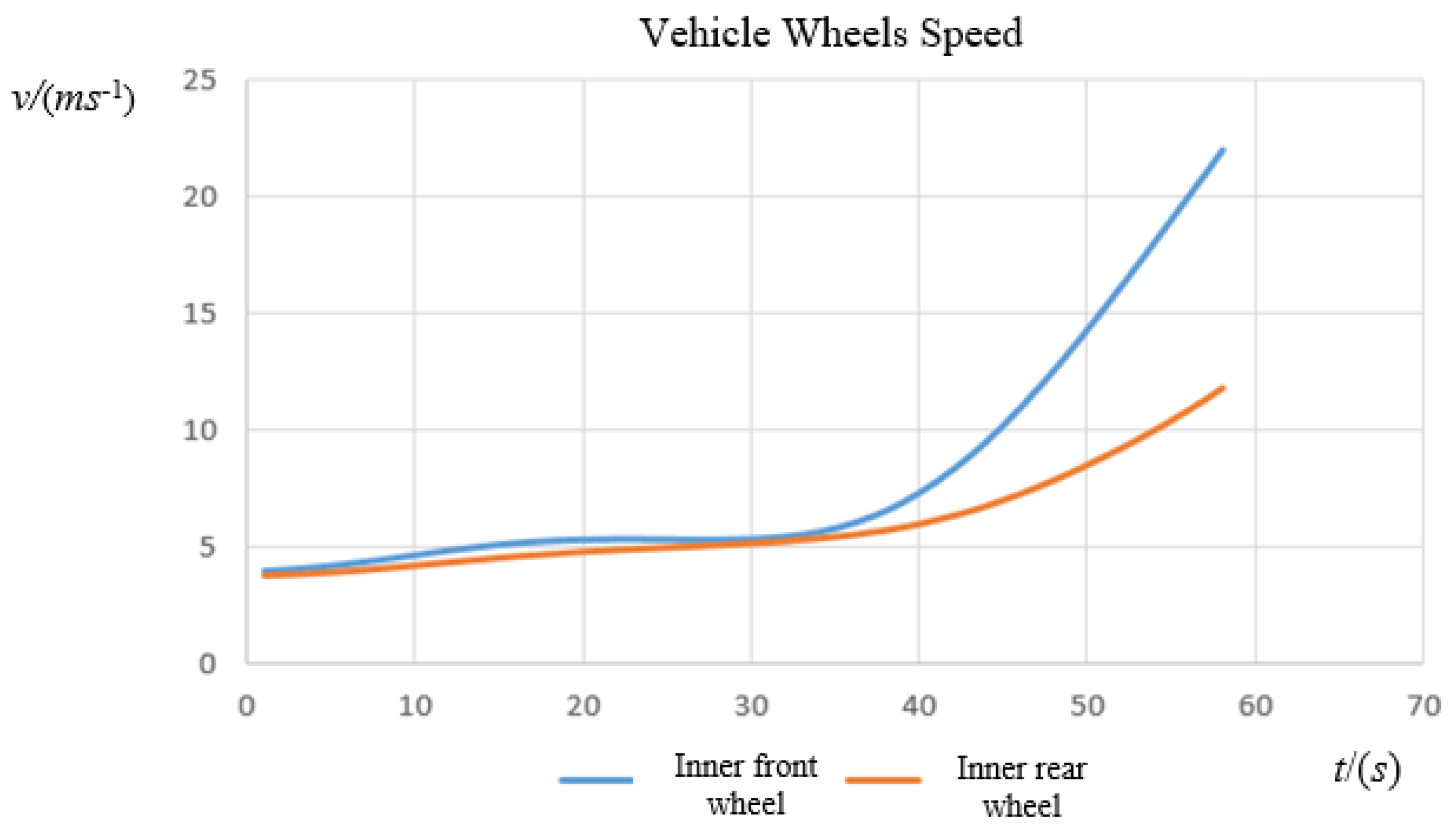

3.3.1. Inner Wheel Trajectory Traffic Characteristics

Displacement Coordinate Changes

Speed Changes

Acceleration Changes

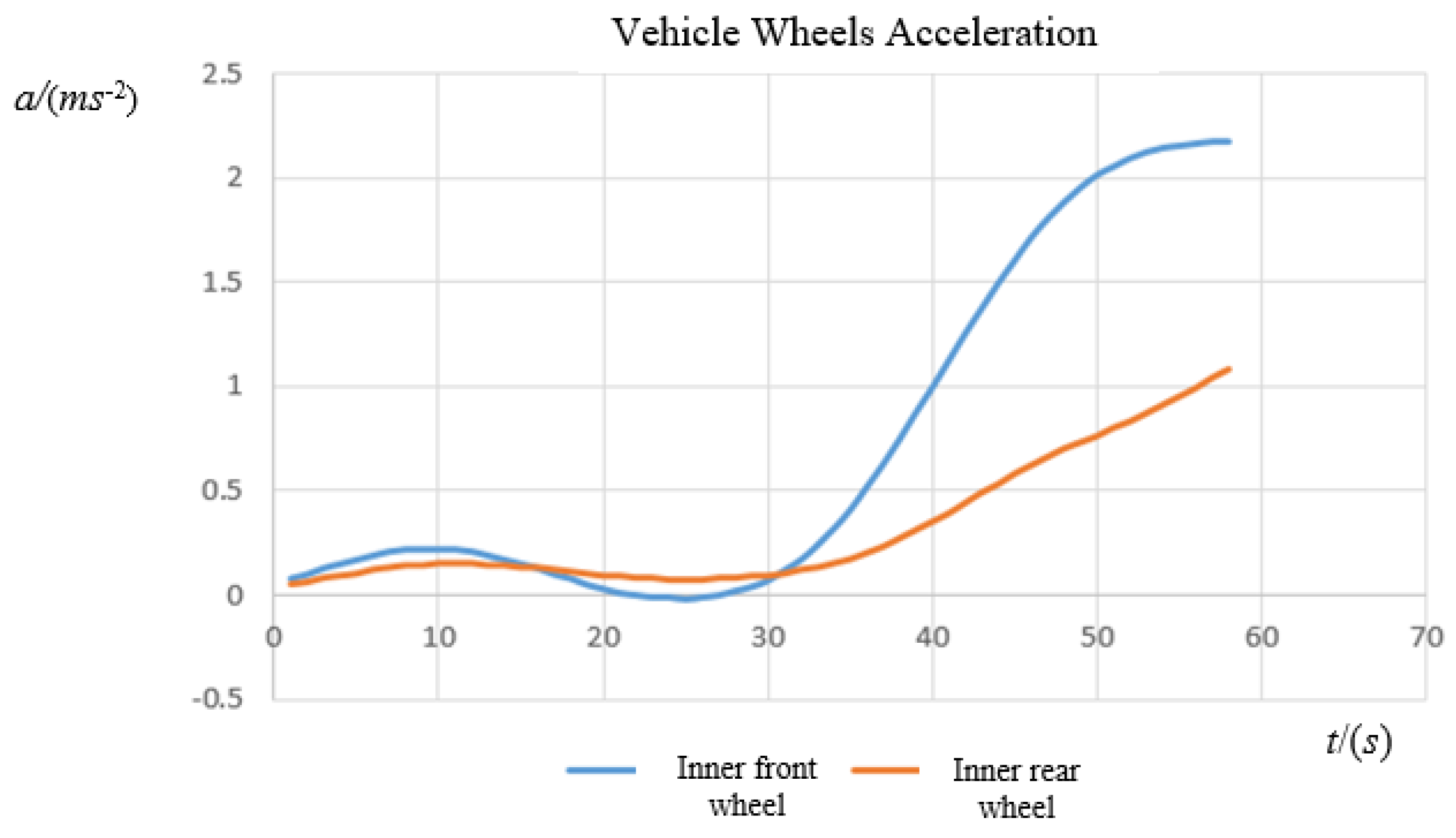

3.3.2. Outer Wheel Trajectory Traffic Characteristics

3.3.3. Risk Differences Between Front and Rear Wheel Trajectories

- ①

- From the perspective of vehicle physical structure, the presence of the differential causes the outer wheels to have a higher forward speed, which results in the outer wheels having a higher collision risk during a vehicle’s right turn.

- ②

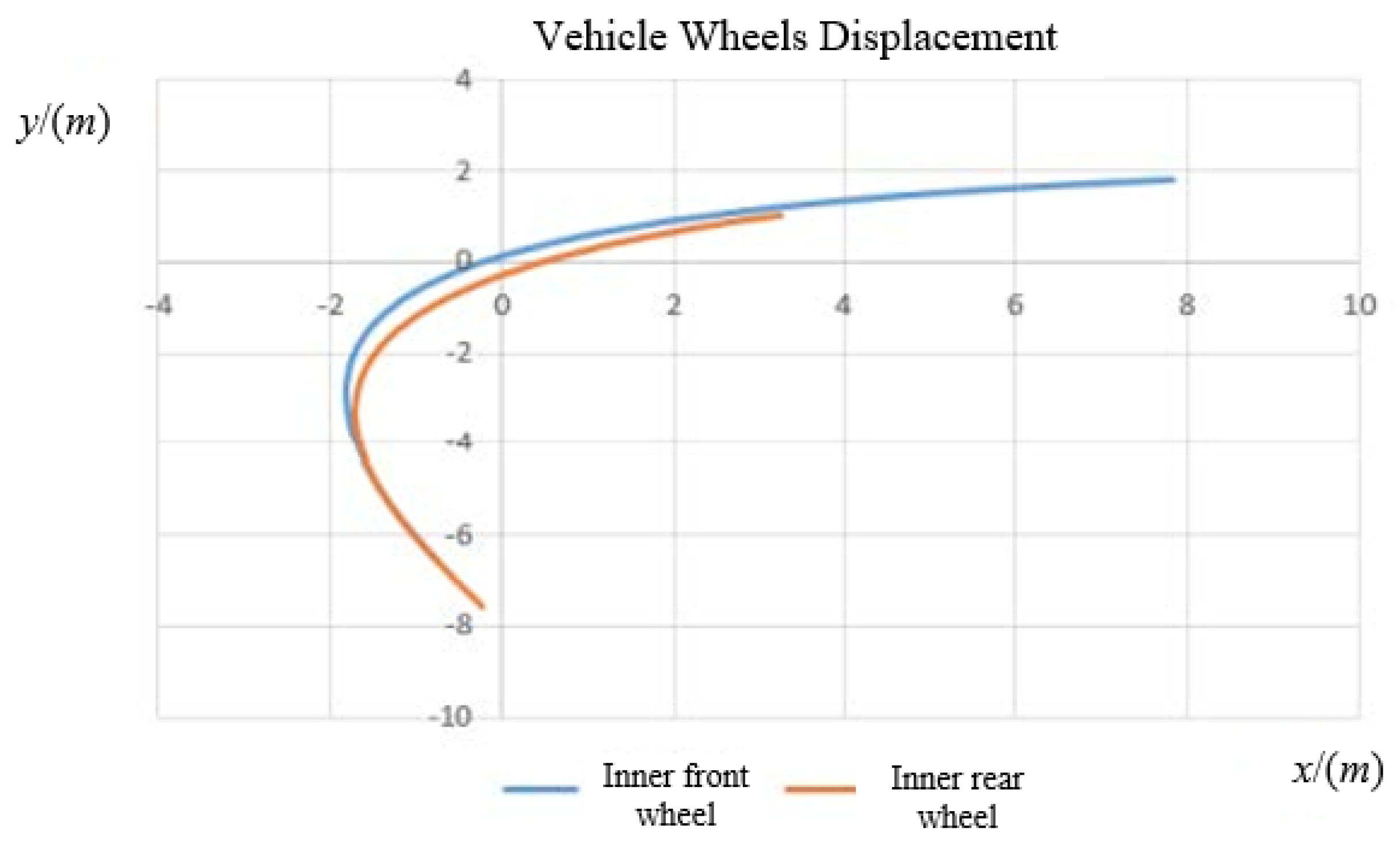

- From the perspective of trajectory differences, due to the front and rear displacement difference in inner wheels in Figure 4 being bigger than the front and rear displacement difference in outer wheels in Figure 7a, and the blind spot around inner wheels which result in pedestrians being easily overlooked in this blind spot, the inner wheels have a higher conflict risk than outer wheels during vehicle turning right.

- ③

- Comparing the speed data of the inner front and rear wheel trajectories, it is found that the front wheel has a higher collision risk than the rear wheel.

- ④

- Similarly, for the outer wheels, the front wheel also has a higher collision risk than the rear wheel.

4. Methodology

4.1. Mathematical Model for Right-Turn Vehicle FRWT

4.1.1. FRWT Modeling

4.1.2. Accuracy Verification of Trajectory Model

4.2. Pedestrian–Right-Turn Vehicle Conflict Risk Assessment

4.2.1. Traffic Behavior Observation and Conflict Severity Classification

Conflict-Avoiding Behavior Observation

- ①

- The pedestrian slows down or stops, or the vehicle accelerates, allowing the vehicle to pass first.

- ②

- The pedestrian accelerates before the vehicle reaches the conflict zone, or the vehicle brakes, stops, or changes its path, allowing the pedestrian to pass first.

- ③

- Both the pedestrian and the vehicle slow down or stop, and after negotiation, one is allowed to pass first.

- ④

- Neither the pedestrian nor the vehicle takes any action.

Conflict Severity Classification

4.2.2. Conflict Indicators and Interaction Pattern Classification

Conflict Indicators Selection and Calculation

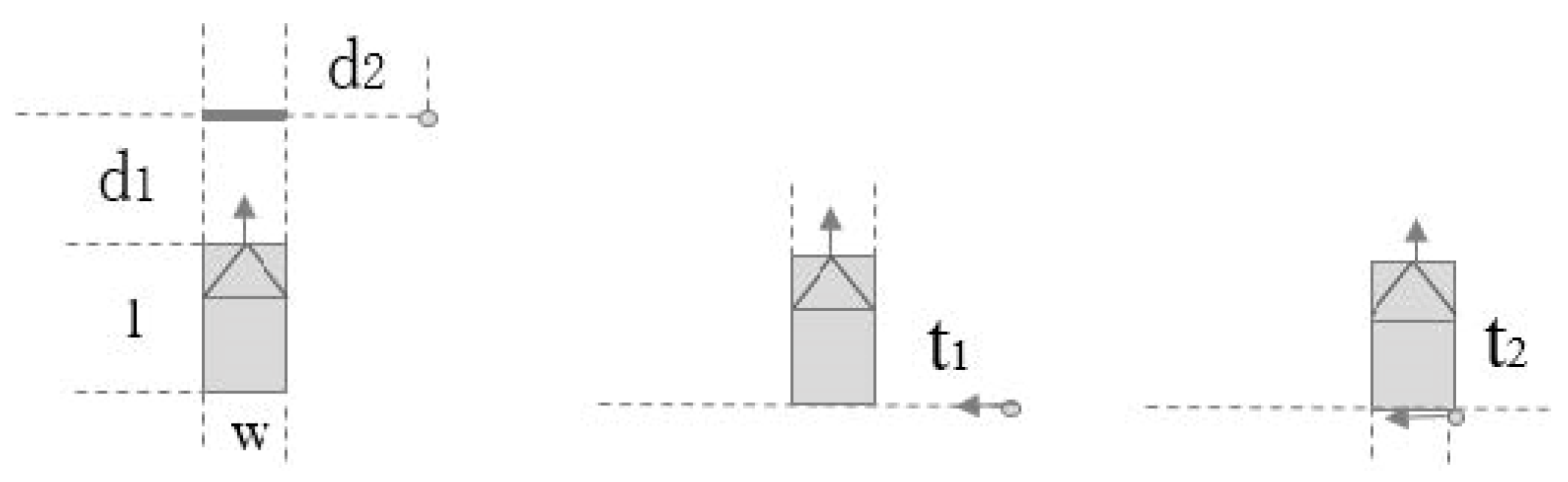

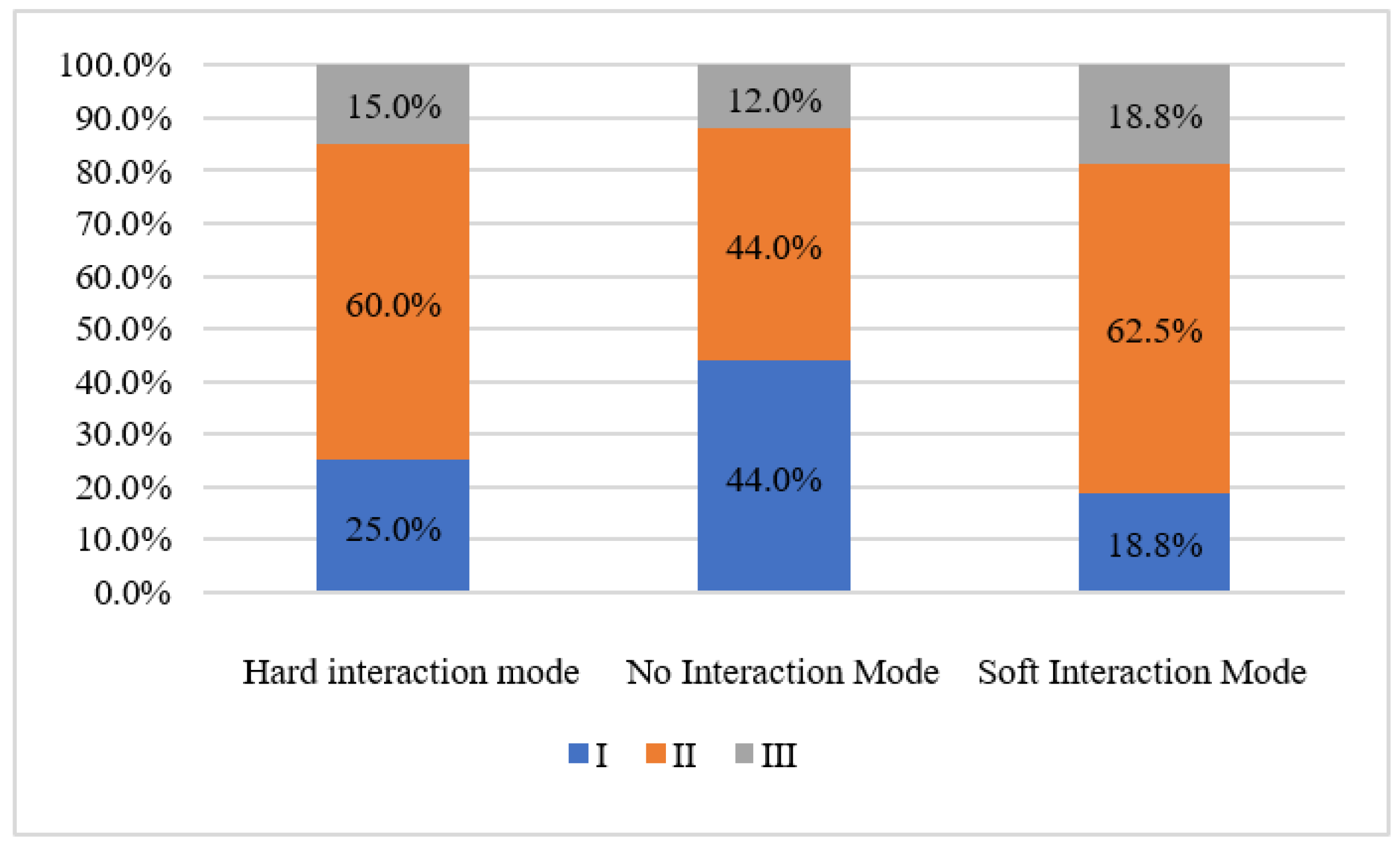

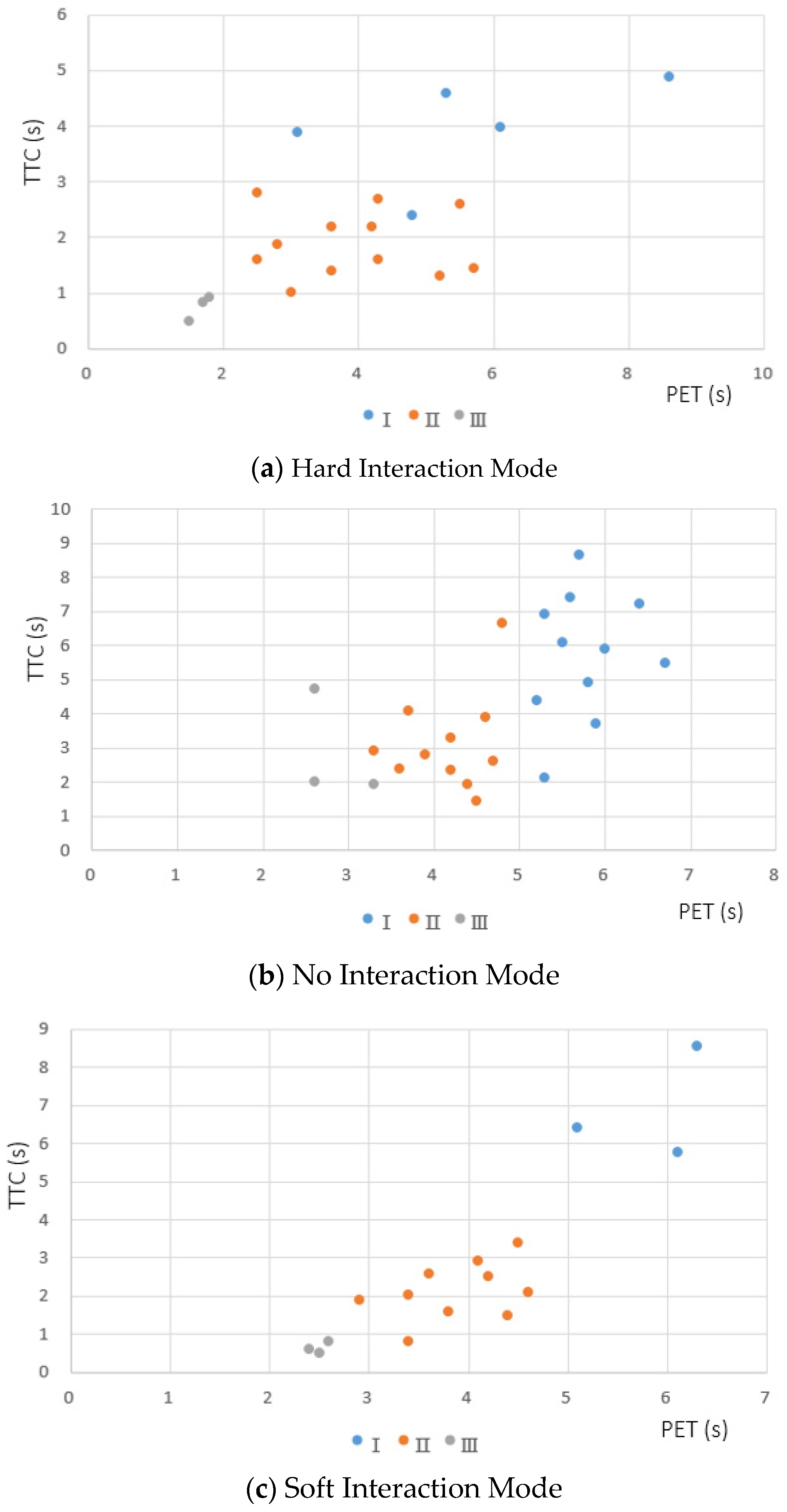

Interaction Modes Classification Based on TTC-GT Curves

- If tb = ta, the event belongs to Mode ① (Hard Interaction Mode);

- If tb = ta & ta = T1 & tb = T2, the event belongs to Mode ② (No Interaction Mode);

- Otherwise, the event belongs to Mode ③ (Soft Interaction Mode).

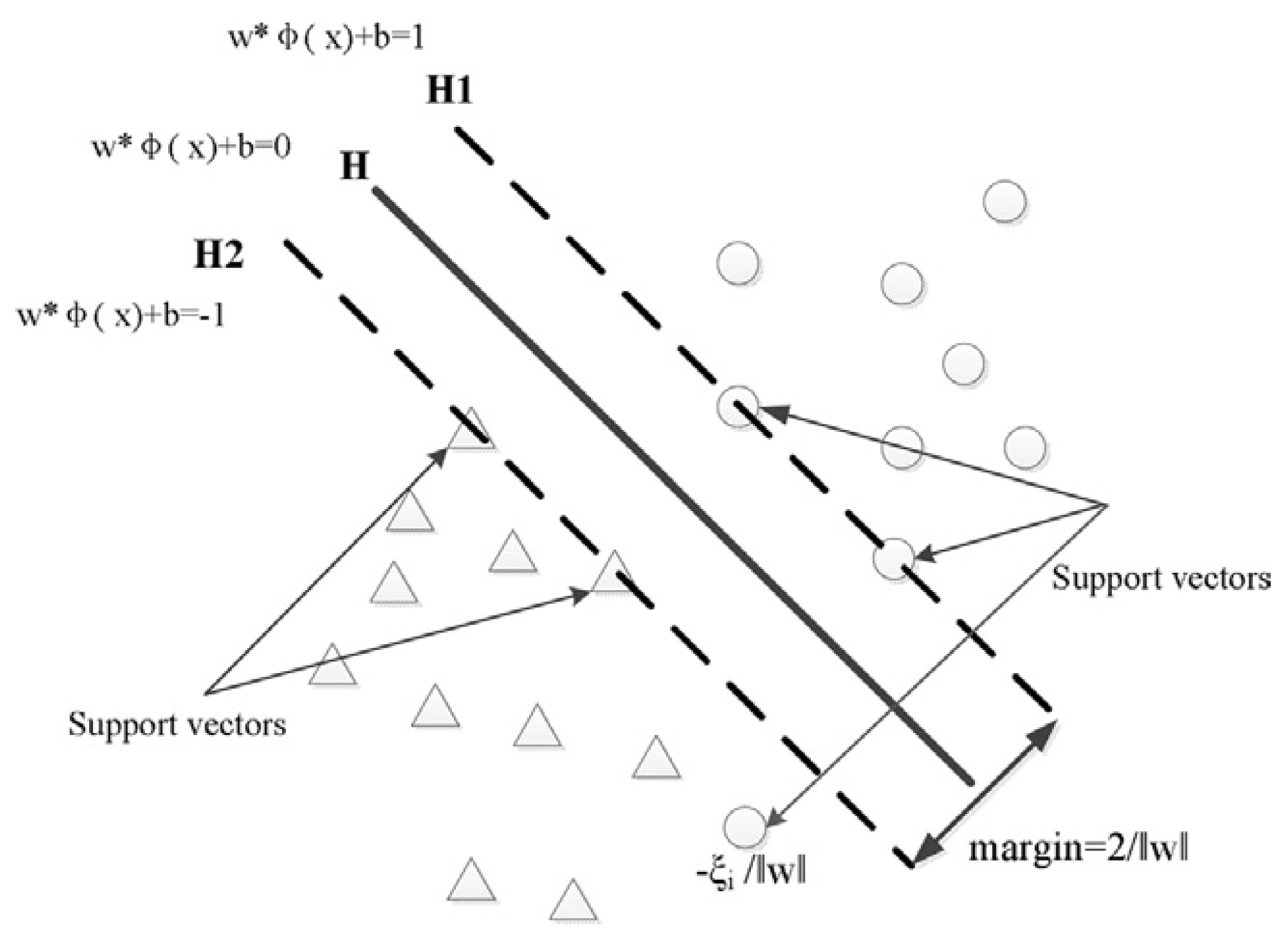

4.2.3. Support Vector Machine Classification Algorithm

5. Results and Discussions

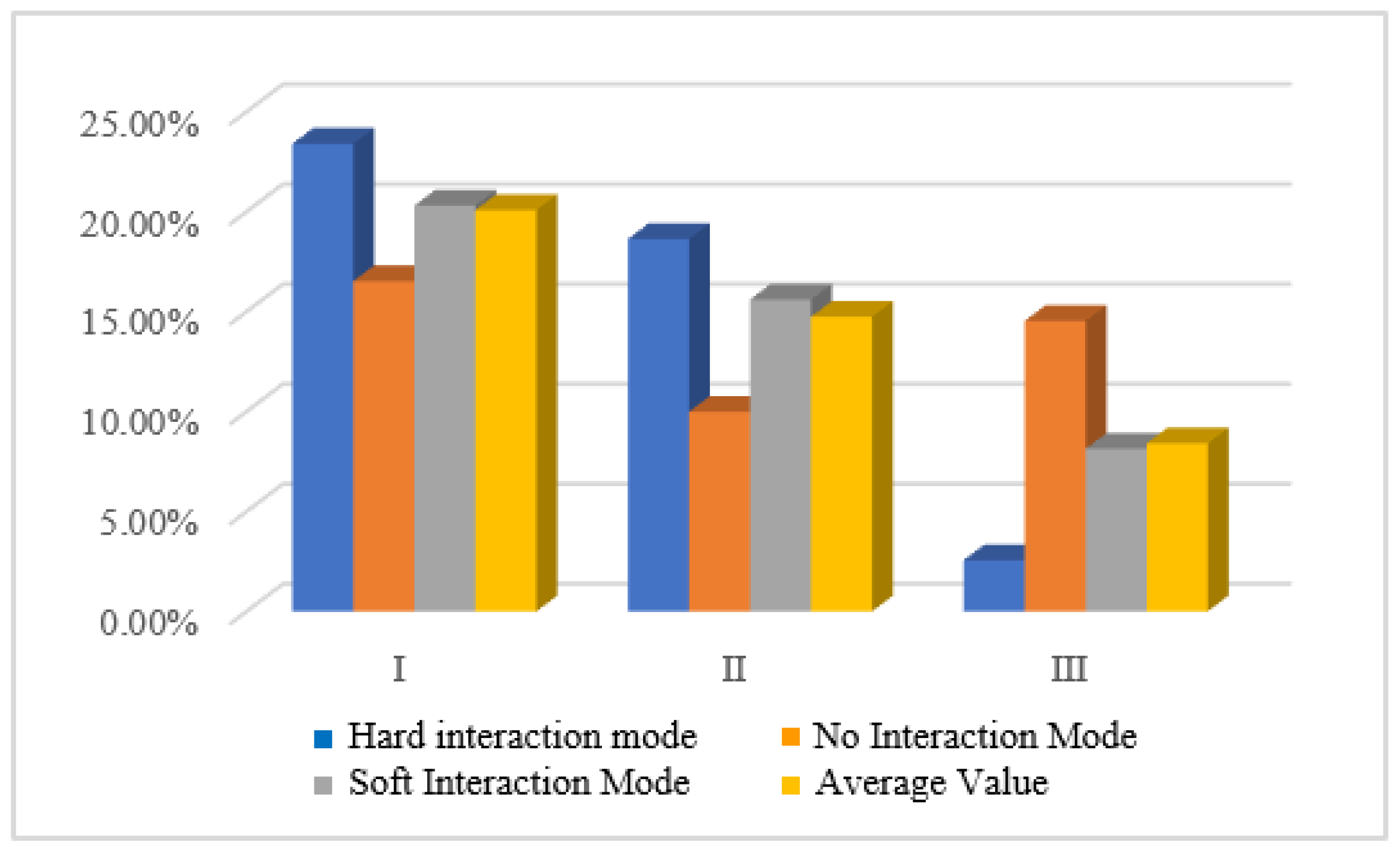

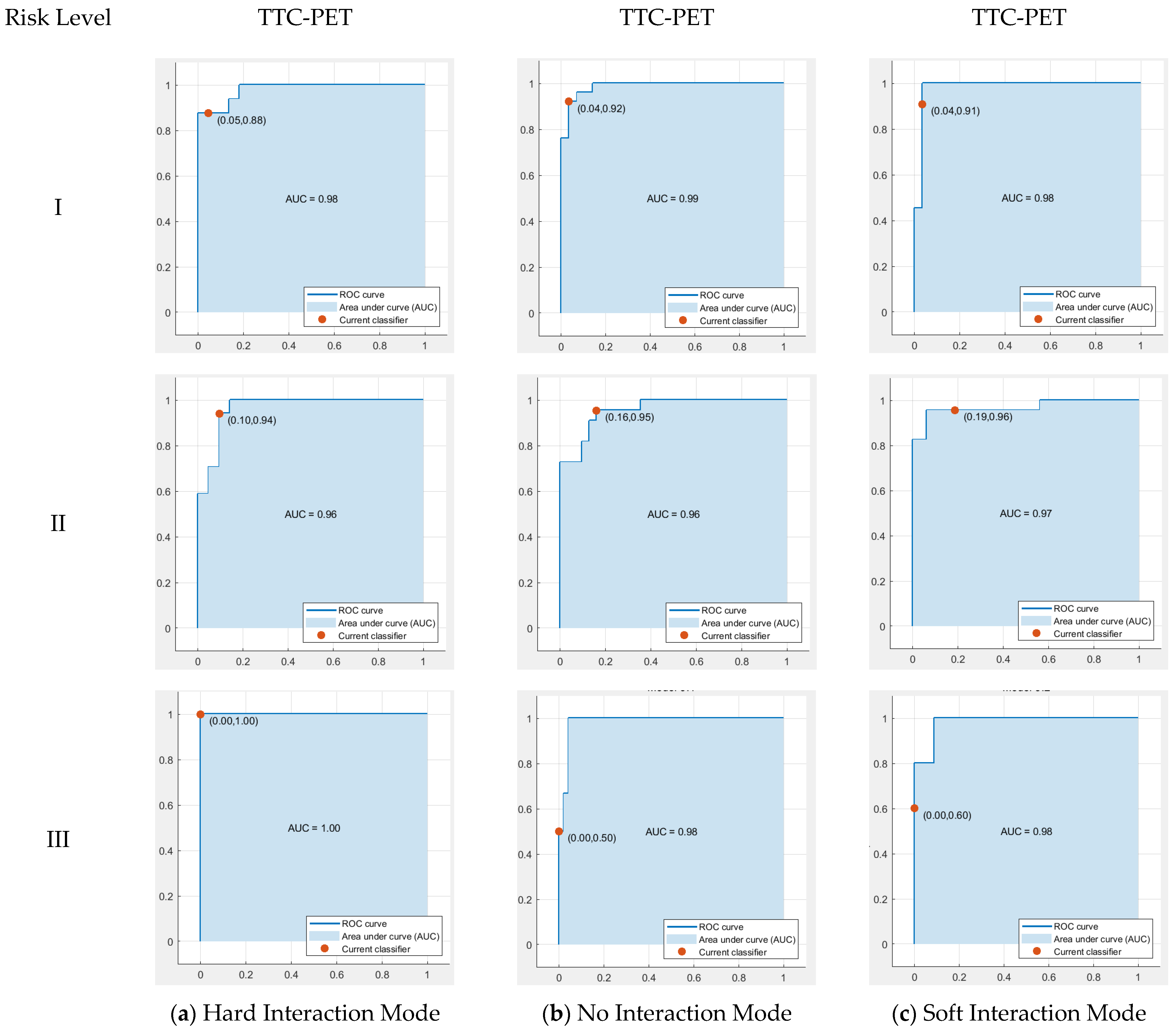

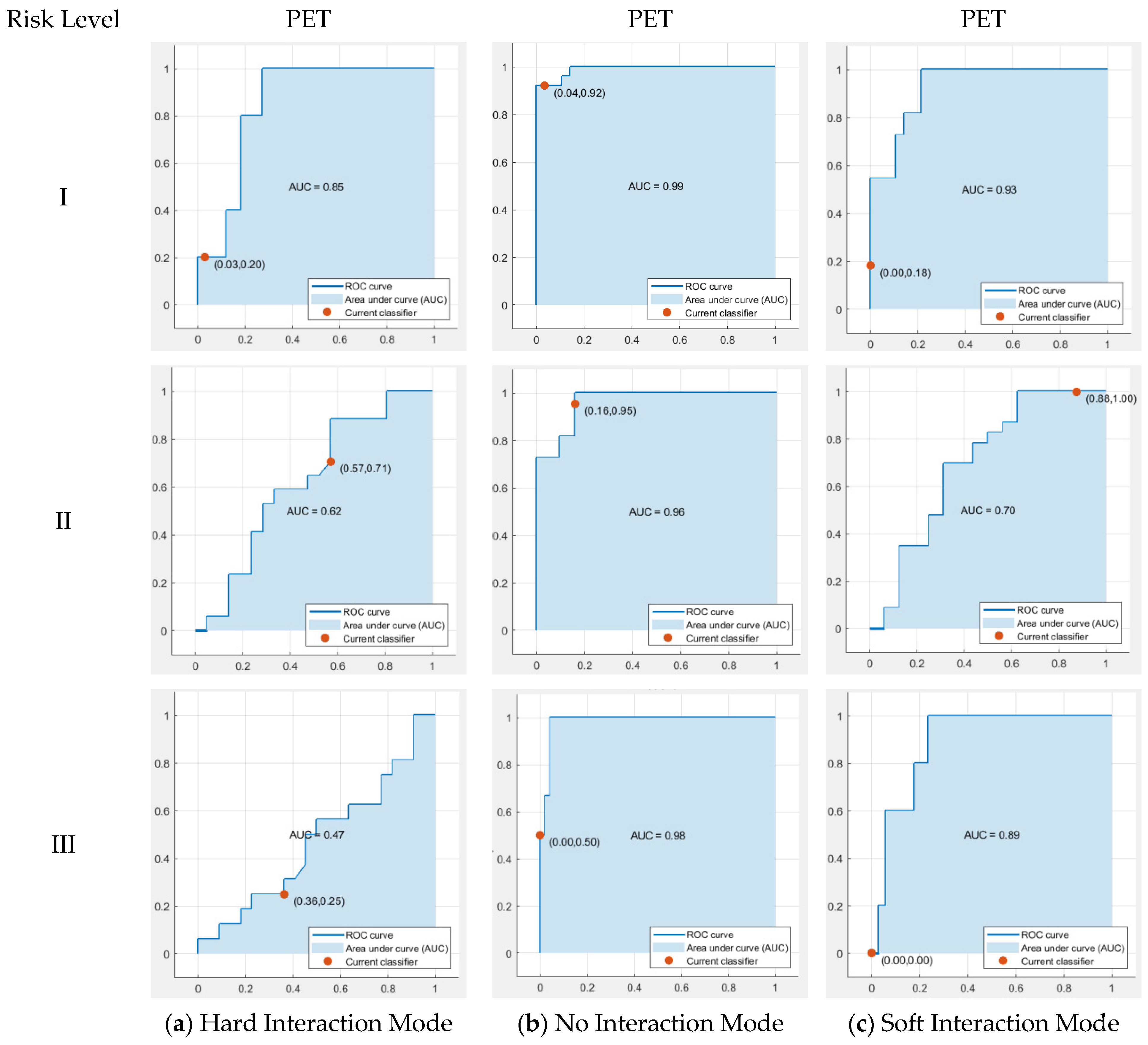

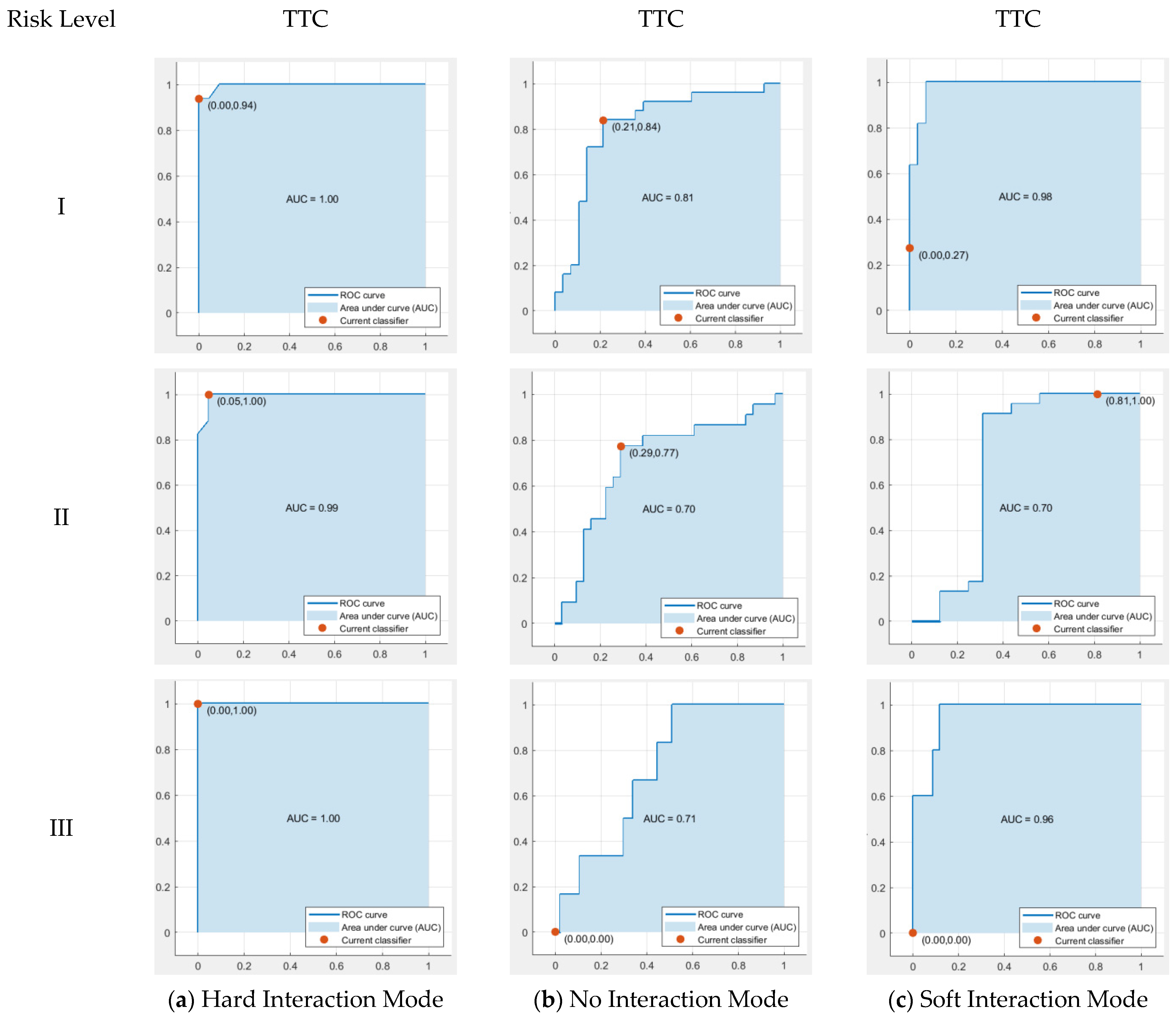

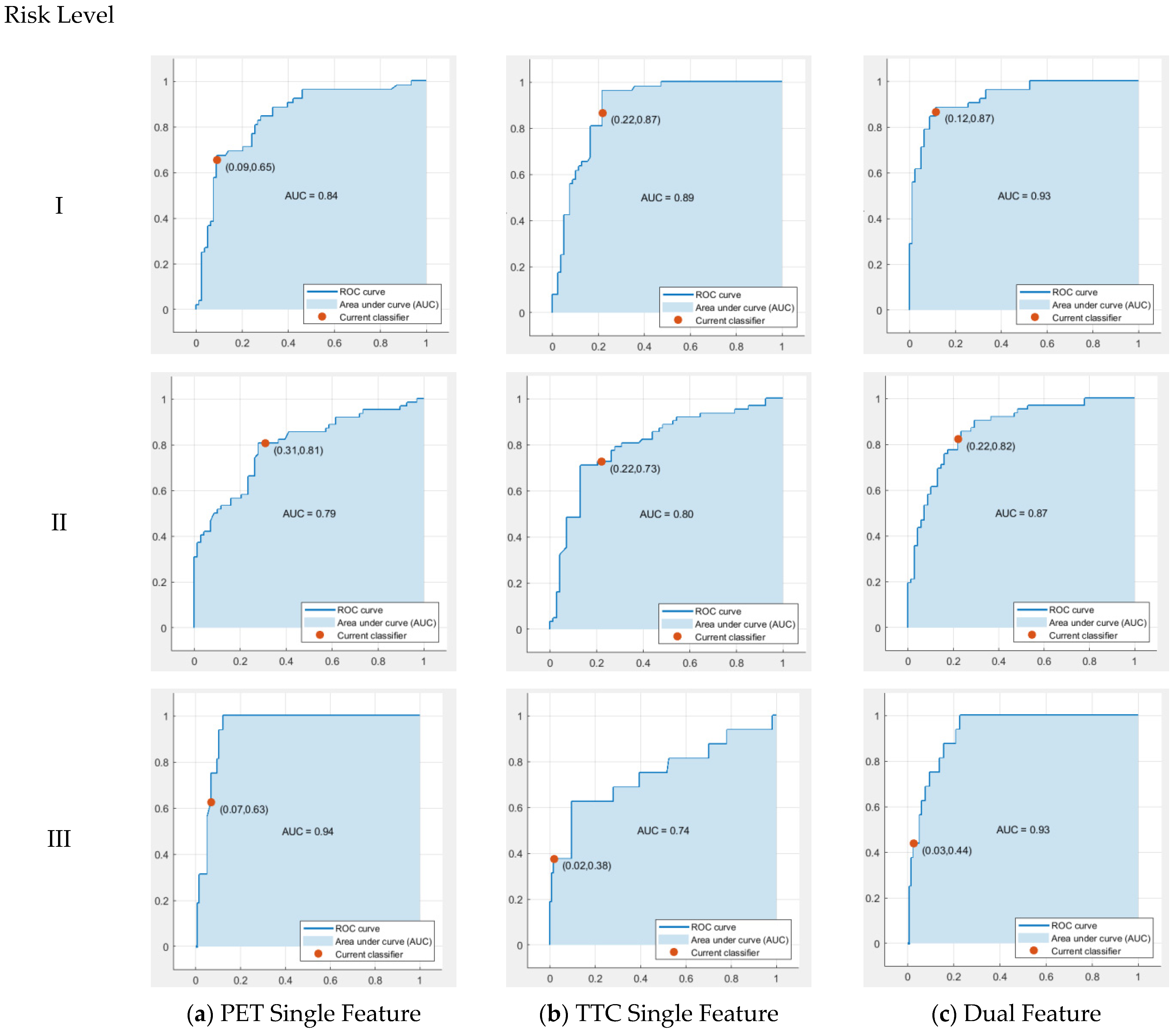

5.1. Analysis of Conflict Indicators Suitability for Three Interaction Modes

5.2. Comparison of Conflict Indicators’ Accuracy for Different Severities

6. Conclusions

- A straightforward demonstration using the extracted R-T vehicle FRWT data indicated that the front wheel presents the highest risk of colliding with pedestrians. The hierarchy of conflict risk is inner front wheel > inner rear wheel > outer front wheel > outer rear wheel.

- A trajectory prediction model of the R-T vehicle based on the FRWT is proposed. The method is useful for accurately and scientifically identifying and analyzing the potential conflicts between R-T vehicles and pedestrians. According to the comparison, the wheel trajectories extracted from the software are consistent with the trajectories obtained from the mathematical model, and the function model trajectories fit the video-extracted trajectories well.

- The severity of conflict risk level is classified by conflict avoidance behavior observation and analyzing the conflict distances in both time and space. Based on these avoidance actions, three risk levels are defined: Risk Level I, Risk Level II, and Risk Level III, for example, at the intersection of Chang’an North Road and Youyi East Road. The results showed that 130 conflicts occurred within 20 min. The counts for Risk Level I, Risk Level II, and Risk Level III conflicts were 52, 62, and 46, respectively.

- Different pedestrian–vehicle interaction conflict modes often exhibit distinct conflict characteristics, and various conflict indicators also vary in applicability across different interaction modes. Three interaction modes—hard, no, and soft—are proposed based on trends in conflict indicators like TTC and GT curves. The SVM classification method was used to categorize risk levels. The results indicated that when TTC-PET dual eigenvalues are used as conflict indicators, the minimum accuracy for the Hard Interaction Mode, No Interaction Mode, and Soft Interaction Mode are 96%, 96%, and 97%, respectively. Under the PET single feature indicator method, the minimum accuracy rates for the three risk interaction modes are 47%, 96%, and 70%, respectively. When using the TTC single feature indicator method, the minimum accuracy rates are 99%, 70%, and 70%, respectively.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, W.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Lv, Y.; Wang, M. A pedestrian trajectory prediction model for Right-turn unsignalized intersections Based on Game Theory. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 9643–9658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Lai, Z.; Tarek, S. A comparison of collision-based and conflict-based safety evaluation of left-turn bay extension. Transp. A Transp. Sci. 2020, 16, 676–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Ijaz, M.; Chen, F.; Easa, S.M.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, J.; Zahid, M. Temporal assessment of injury severities of two types of pedestrian-vehicle crashes using unobserved-heterogeneity models. J. Transp. Saf. Secur. 2024, 16, 820–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasernejad, P.; Sayed, T.; Alsaleh, R. Multiagent modeling of pedestrian-vehicle conflicts using Adversarial Inverse Reinforcement Learning. Transp. A Transp. Sci. 2023, 19, 2061081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Liang, G.; Chen, Y.; Yang, X.; Liu, Y. Study on the risk assessment of pedestrian-vehicle conflicts in channelized right-turn lanes based on the hierarchical-grey entropy-cloud model. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2024, 205, 107664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Q.; Abdel-Aty, M.; Wang, C.; Tang, S. Assessing conflict likelihood and its severity at interconnected intersections: Insights from drone trajectory data. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2025, 213, 107943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, F.; Ali, Y.; Li, Y.; Haque, M.M. Revisiting the hybrid approach of anomaly detection and extreme value theory for estimating pedestrian crashes using traffic conflicts obtained from artificial intelligence-based video analytics. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2024, 199, 107517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.; Li, Z.; Levin, M.W. Evasion planning for autonomous intersection control based on an optimized conflict point control formulation. J. Transp. Saf. Secur. 2022, 14, 2074–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, Z.; Yang, Y.; Qi, L.; Ke, R. High-resolution vehicle trajectory extraction and denoising from aerial videos. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 22, 3190–3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, F.; Whitley, T.; Xu, H.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Hui, T.; Tian, Y. Vehicle-pedestrian interaction analysis for evaluating pedestrian crossing safety at uncontrolled crosswalks—A geospatial approach using multimodal all-traffic trajectories. J. Saf. Res. 2024, 91, 326–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, K.; Ozbay, K.; Yan, H. Mining automatically extracted vehicle trajectory data for proactive safety analytics. Transp. Res. 2019, 106, 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.J.; Park, H.C.; Ham, S.W.; Kho, S.Y.; Kim, D.K. Extracting vehicle trajectories using unmanned aerial vehicles in congested traffic conditions. J. Adv. Transp. 2019, 2019, 9060797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhong, Y. Vehicle trajectory extraction method based on distributed fiber optic sensing system. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2021, 53, 141–150. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, L.; Li, W. A vehicle trajectory extraction method based on MapReduce. Comput. Knowl. Technol. 2019, 15, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, J.; Wang, R.; Qin, X.; Yin, X. Vehicle trajectory stop point extraction algorithm based on semantic behavior. J. Tonghua Norm. Univ. 2021, 42, 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X. Multi-target vehicle trajectory automatic collection method based on deep learning. Transp. Sci. Technol. 2021, 135–140, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.; Zhao, J.; Dick, C.T.; Liu, X.; Bian, Z.; Kirkpatrick, S.W.; Lin, C.Y. Probabilistic risk analysis of unit trains versus manifest trains for transporting hazardous materials. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2023, 181, 106950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mario, S.; Belén, R.; Ana, S. Safety assessment on pedestrian crossing environments using MLS data. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2018, 111, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, F.; Wang, X.; Sun, C. Risk evaluation for conflicts between crossing pedestrians and right-turn vehicles at intersections. Transp. Res. Rec. 2021, 2675, 1005–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, A.; Huang, Z.; Li, W.; Qin, H.; Kang, D.; Liu, X. Artificial intelligence-aided grade crossing safety violation detection methodology and a case study in New Jersey. Transp. Res. Rec. 2023, 2677, 688–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pin, C.; Sayed, T.; Zaki, M. Assessing safety improvements to pedestrian crossings using automated conflict analysis. Transp. Res. Rec. 2015, 2514, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Zeng, W.; Yu, G. Assessing right-turn vehicle-pedestrian conflicts at intersections using an integrated microscopic simulation model. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2019, 129, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amini, R.; Yang, K.; Antoniou, C. Development of a conflict risk evaluation model to assess pedestrian safety in interaction with vehicles. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2022, 175, 106773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theissen, P.; Wojciak, J.; Heuler, K.; Demuth, R.; Indinger, T.; Adams, N. Experimental Investigation of Unsteady Vehicle Aerodynamics Under Time-Dependent Flow Conditions-Part; SAE Technical Paper: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Heft, A.I.; Indinger, T.; Adams, N.A. Experimental and numerical investigation of the DrivAer model. In Fluids Engineering Division Summer Meeting; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Volume 44755, pp. 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Xu, S.; Wang, Q.; Bao, H.; Wang, Y. Review of automotive aerodynamics research based on physical models. Exp. Fluid Mech. 2020, 34, 38–48. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, W.; Wang, H.; Ding, L. Automotive aerodynamics simulation analysis based on DrivAer model. In Proceedings of the 2022 Academic Annual Conference of the Automotive Aerodynamics Branch of the Chinese Society of Automotive Engineering—Pneumatic Branch Venue, Shanghai, China, 20–21 October 2022; pp. 165–170. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, B.; Chen, H.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, Q. Trajectory-Based Study on the Conflict Characteristics of Pedestrians and Non-Motorized Vehicles at Bus Stops. In Proceedings of the CICTP 2021, Xi’an, China, 16–19 December 2021; pp. 973–984. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, P.; Bai, Y.; Lei, X.; Yu, X. An Investigating Study on Lateral Riding Position of Cyclists from Curb Based on Road Segment Scope Trajectory Data. In Proceedings of the CICTP 2024, Shenzhen, China, 23–26 July 2024; pp. 922–932. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, Y.; Wang, M.; Sun, J.; Li, K. Evaluation of pedestrian safety at intersections: A theoretical framework based on pedestrian-vehicle interaction patterns. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2016, 96, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheykhfard, A.; Haghighi, F.; Papadimitriou, E.; Van Gelder, P. Review and assessment of different perspectives of vehicle-pedestrian conflicts and crashes: Passive and active analysis approaches. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. 2021, 8, 681–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vapnik, V.N. Statistical Learning Theory; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

| Right-Turning Vehicle on Intersection Entrances | Conflict Avoidance Measure | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ① | ② | ③ | ④ | ||

| Chang’an North Road—South Entrance | 3 | 39 | 8 | 4 | 54 |

| Youyi East Road—East Entrance | 1 | 13 | 2 | 1 | 17 |

| Youyi East Road—West Entrance | 1 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 13 |

| Chang’an North Road—North Entrance | 3 | 26 | 2 | 5 | 36 |

| Total | 8 | 87 | 13 | 12 | 130 |

| Element | Risk Level I | Risk Level II | Risk Level III | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrances | 52 | 62 | 46 | 130 |

| 0.34 | 1.21 | 2.06 | — | |

| 0.25 | 0.42 | 0.32 | — |

| Element | South Entrance | East Entrance | West Entrance | North Entrance | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event order | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| PET | 4.20 | 2.60 | 4.40 | 5.30 | 6.30 | 3.00 | 6.10 | 5.50 | 5.90 | 1.8 | 2.8 | 4.5 | 2.6 |

| TTCmin | 2.33 | 1.99 | 1.48 | 2.13 | 8.54 | 1.01 | 3.98 | 2.59 | 3.72 | 0.93 | 1.87 | 1.43 | 4.74 |

| GTmin | 0.118 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 3.05 | 0.29 | 0.04 | 0.26 | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 1.10 | 4.46 |

| Severity | II | III | II | I | I | II | I | II | I | III | II | II | III |

| Right-Turn Vehicle on Intersection Entrances | Hard Interaction Mode | No Interaction Mode | Soft Interaction Mode | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chang’an North Road—South Entrance | 18 | 29 | 7 | 54 |

| Youyi East Road—East Entrance | 7 | 4 | 6 | 17 |

| Youyi East Road—West Entrance | 4 | 3 | 6 | 13 |

| Chang’an North Road—North Entrance | 9 | 17 | 10 | 36 |

| Total | 38 | 53 | 39 | 130 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, R.; Liang, G.; Wang, C.; Easa, S.M.; Deng, Y.; Wang, B.; Mao, Y. Conflict Risk Assessment Between Pedestrians and Right-Turn Vehicles: A Trajectory-Based Analysis of Front and Rear Wheel Dynamics. Infrastructures 2025, 10, 330. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures10120330

Li R, Liang G, Wang C, Easa SM, Deng Y, Wang B, Mao Y. Conflict Risk Assessment Between Pedestrians and Right-Turn Vehicles: A Trajectory-Based Analysis of Front and Rear Wheel Dynamics. Infrastructures. 2025; 10(12):330. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures10120330

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Rui, Guohua Liang, Chenzhu Wang, Said M. Easa, Yajuan Deng, Baojie Wang, and Yi Mao. 2025. "Conflict Risk Assessment Between Pedestrians and Right-Turn Vehicles: A Trajectory-Based Analysis of Front and Rear Wheel Dynamics" Infrastructures 10, no. 12: 330. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures10120330

APA StyleLi, R., Liang, G., Wang, C., Easa, S. M., Deng, Y., Wang, B., & Mao, Y. (2025). Conflict Risk Assessment Between Pedestrians and Right-Turn Vehicles: A Trajectory-Based Analysis of Front and Rear Wheel Dynamics. Infrastructures, 10(12), 330. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures10120330