1. Introduction

The 21st century marks a new stage in the development and utilization of infrastructure in China, ushering in a period of rapid engineering development [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Engineering construction projects are increasingly confronted with complex geological environments [

7]. During these projects, issues related to surrounding rock stability, such as hydraulic coupling, soft rock expansion, disintegration, and softening, frequently arise [

8], leading to substantial economic losses and casualties [

9].

Given the critical nature of engineering safety, many scholars and experts have recently focused on the physical and mechanical properties, deformation characteristics, and instability modes of rock masses in engineering construction. Li Yong et al. [

10] conducted experiments to investigate the physical and mechanical properties of rock masses, providing valuable parameters for slope stability assessments. Yan Jie et al. [

11] employed a slope sliding model to determine the time-varying characteristics of deformation in weak surrounding rocks, considering the influence of seepage coefficients. Sun et al. [

12] demonstrated that employing double-layer primary support can significantly slow the development of large deformations in weak surrounding rocks. Zhao et al. [

13] used a true triaxial test system to thoroughly examine the impact of weak interlayer thickness on the mechanical response and failure behavior of rock masses near the free surface. Zhu et al. [

14] highlighted that both shear and tensile failures occur on joint surfaces. However, shear failure is the primary factor controlling the peak strength of rock masses, whether or not anchor rods are used. With the advancement of computing technologies, experts have applied neural networks and numerical simulations to build databases, enabling predictions and analyses of surrounding rock deformation under various support parameters [

15,

16]. For weak surrounding rocks, advanced support techniques have been shown to reduce the unique release coefficient (λ) and constant (D) of the surrounding rock, thereby minimizing contact load between the surrounding rock and initial support structures [

17]. Research by Deng et al. [

18] indicates that grouting surrounding rock masses can reduce the damage range by approximately 26–64%, compared to ungrouted masses. Additionally, on-site comprehensive investigations and early warning systems for large deformations of surrounding rock can ensure safety and stability [

19].

The aforementioned scholars have made significant contributions to the research on the stability of rock masses, but most of their research focuses mainly on static mechanics or a single method. This paper takes the Shengjiang slope at the Baala Hydropower Station as the engineering background, and uses PS-insar remote sensing technology, FLAC3D numerical simulation, and FLOW-3D wave numerical simulation to analyze the stability of the slope and the surrounding rock from the perspective of combining static mechanics and dynamics, providing scientific references for the stability research of other near-water slopes.

The stability of the surrounding rock of near-water slopes is significantly affected by the coupling of “geological deformation-hydraulic load”. The surge disaster caused by the instability of such slopes is one of the core safety risks of water conservancy hub projects. This paper takes the Sejiang slope of the Baala Hydropower Station as a typical research object. This area has high and steep terrain and potential risks of instability of deformation bodies. The current research has the following key issues: (1) There is a lack of high-precision monitoring methods for the spatio-temporal evolution characteristics of long-term geological deformation of the slope; (2) The mechanical response mechanism of the surrounding rock of the slope after the instability of the deformation body has not been clarified; (3) The influence of the surge caused by the instability and entry into the water on the hydraulic load of the slope and the hub has not been quantified.

Clarify the research objectives and tasks for the above key issues. Overall objective: To reveal the coupling mechanism of “geological deformation-rock mass mechanical response-wave-induced hydrodynamic load” on the Sejiang slope of the Baala Hydropower Station, and to establish a multi-technology collaborative analysis method for the stability of the near-water slope rock mass. To achieve the above objectives, the following three core tasks will be carried out: (1) Use high-precision PS-insar monitoring technology to identify the spatiotemporal distribution characteristics of geological deformation on the Xiongjiang slope; (2) Build a FLAC3D numerical model to analyze the mechanical response and failure laws of the slope rock mass under the instability of the deformation body; (3) Quantify the wave load caused by the instability of the deformation body entering the water, and evaluate its impact on the slope and the powerhouse.

2. Engineering Geological Survey

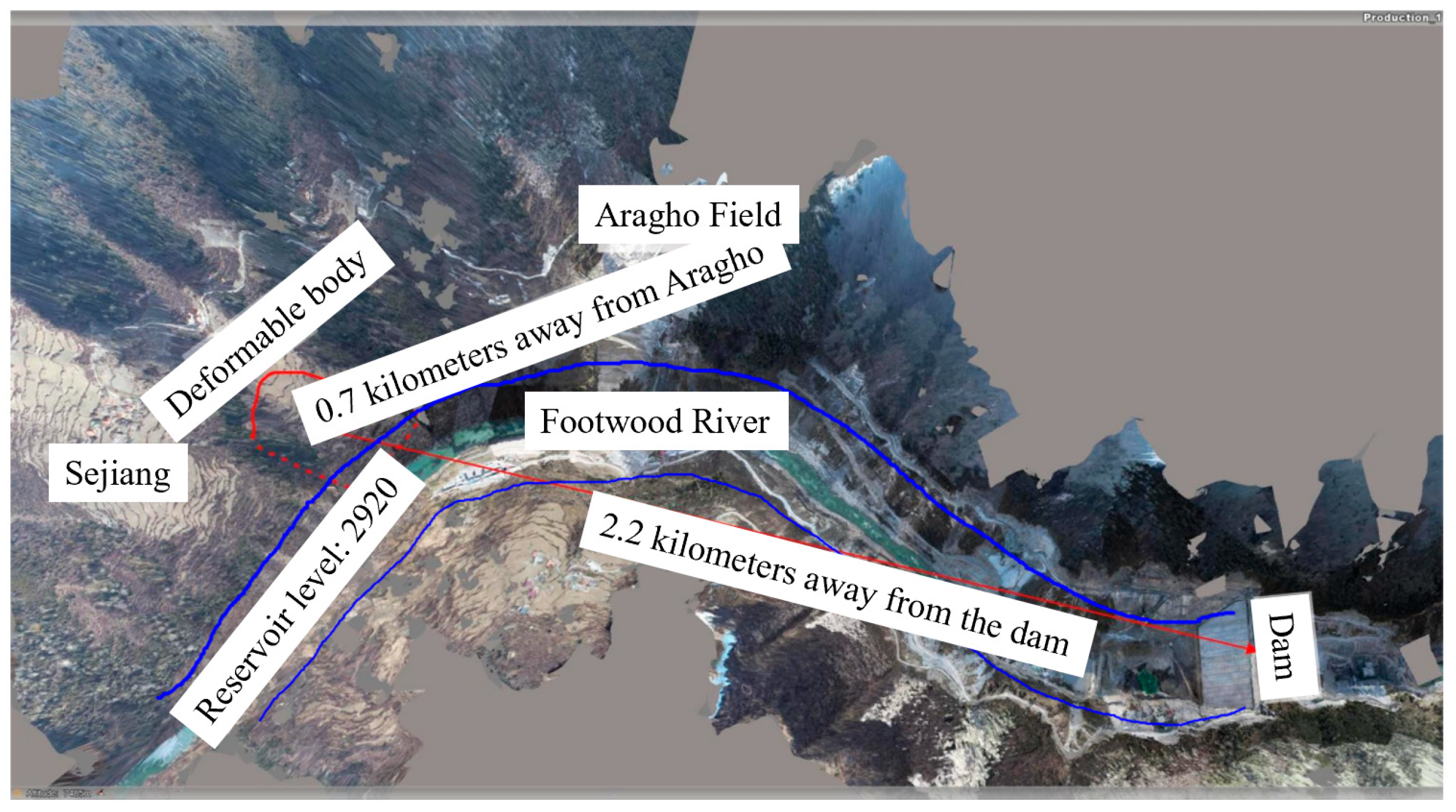

The core research area of the slope is located on the left bank of the Balaxia Hydropower Station reservoir, 2.2 km away from the dam in a straight line. It is situated on a thin ridge slope between Shanshugou (upstream) and Geduigou (downstream), with a typical terrain feature of “surrounded by gullies on both sides and facing the river at the front”. The sensitive objects and hydraulic structures within the area include: the main project of the downstream dam, the reservoir bank slope protection structure, and the residential areas on both sides of the Deformation Body Road.

The river course in the study area generally takes a “bow” shape: the flow direction of the river section where the deformation body is located is S30° E, and it turns to S25° W after passing through the deformation body. After crossing the Ya La Gully, it further changes to S60° W and flows directly towards the dam. The riverbed elevation at the deformation body is approximately 2825 m, and the original natural valley width is about 80 m. Under the normal storage water level (2900 m), the river surface width expands to about 330 m (

Figure 1).

Core risk scenario: Based on the historical records of regional geological disasters and the requirements of engineering safety assessment, “the overall instability and submersion of a 2.1 million cubic meter deformation body” is set as the extreme risk scenario (corresponding to the most unfavorable geological conditions). The focus is on assessing the damage risks to the downstream dam, slope protection structures, and surrounding sensitive objects caused by wave impact and slope sliding under this scenario. The risk determination is based on the “Standard for Risk Classification of Near-Basin Slopes” in the “Code for Geotechnical Investigation of Hydropower Projects”.

To ensure the accuracy of the research data and the credibility of the results, it is necessary to clearly define the sources, parameters and verification standards of all input data: The basic geological data comes from the preliminary geological investigation report of the Baala Hydropower Station, including the lithological stratification data of 3 borehole profiles (with a depth of 30–50 m), and the physical and mechanical parameters of the sliding zone soil (natural density 1.8–1.9 g/cm3, moisture content 18–22%). The data has been verified through indoor triaxial shear tests (with a minimum of 6 test groups and a parameter variation coefficient of ≤8%). The slope safety determination criteria refer to the “Hydroelectric Engineering Slope Design Code”. The landslide stability is regarded as “stable-creep-type landslide”. The strength reduction method is used to calculate the slope safety factor. It is stipulated that Fs ≥ 1.2 represents a stable state, 1.0 ≤ Fs < 1.2 represents a basically stable state, and Fs < 1.0 represents an unstable state. The wave safety control standard takes the design flood level of the dam (2928 m) as the threshold. The superimposed wave height must not exceed this elevation when added to the normal water storage level.

3. Regional Deformation Analysis Based on PS-Insar

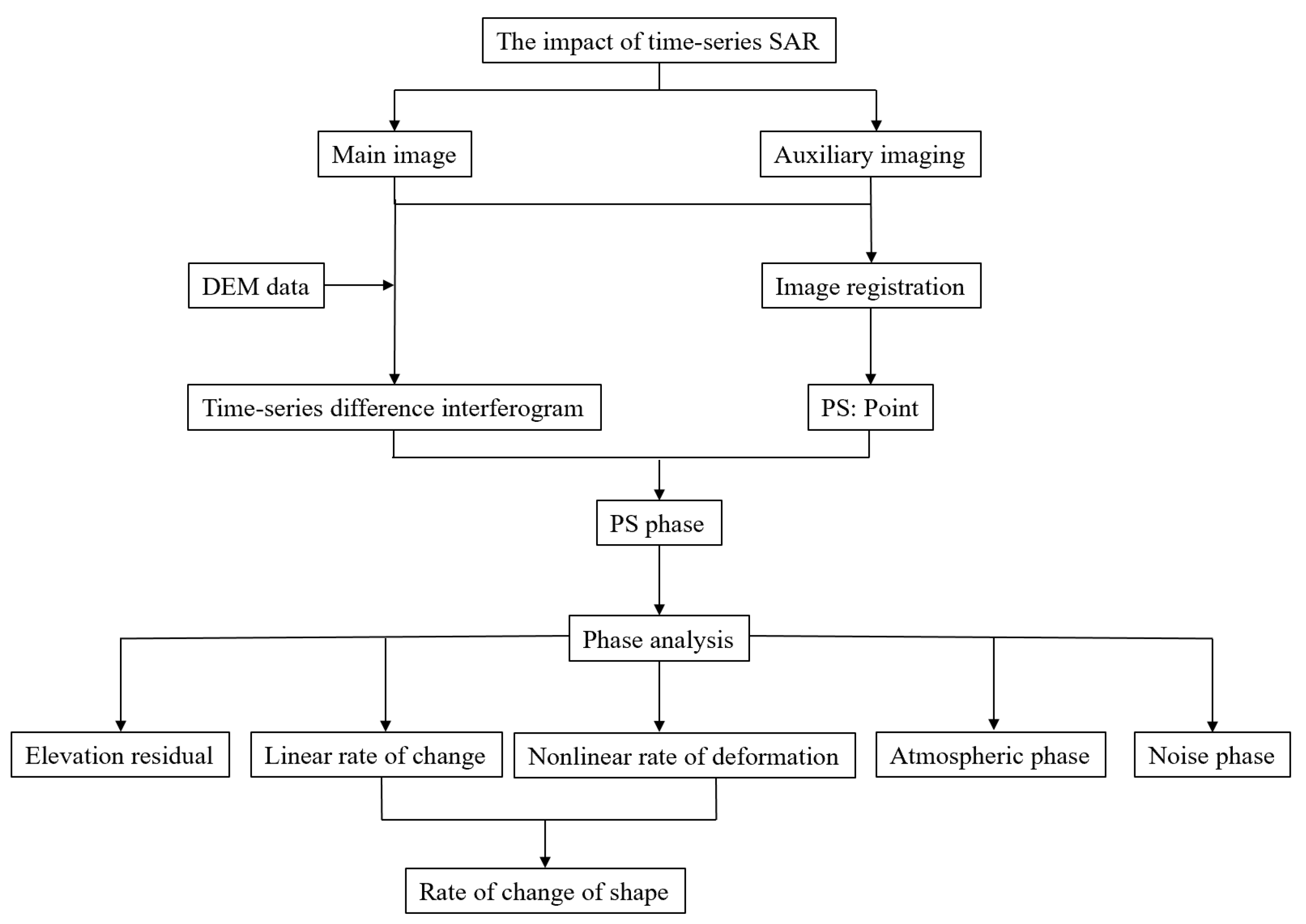

Synthetic Aperture Radar Interferometry (InSAR) relies on the phase difference between two or more radar echo images to infer the three-dimensional information of the surface and the temporal deformation. However, traditional InSAR is affected by issues such as temporal-spatial decorrelation, atmospheric time-varying phase, and orbit errors, and thus has limitations in long-term sequence and high-resolution deformation monitoring.

“Persistent Scatterer InSAR” (PSInSAR) significantly reduces the effects of decorrelation and phase noise by selecting “persistent scatterers (PS)” pixels that exhibit high coherence across dozens to hundreds of images from the scene. This approach provides an effective means for long-term deformation monitoring with centimeter-to-millimeter accuracy. The technical flowchart is shown in

Figure 2.

3.1. Regional Deformation Analysis

As shown in

Figure 3: The PS-InSAR time-series inversion results (shown as colored dots in the figure) indicate that within the 4 years and 2 months observation period, the cumulative displacement along the line of sight (LOS) in the study area ranged from −11 mm to +166 mm. The spatial distribution showed a distinct NW–SE oriented band-like difference:

The central-southeastern core zone (the area where the red lines are located and the pink-yellow-red pixels are concentrated) has a cumulative displacement of 50 mm–>110 mm, with an annual average rate of approximately 12–26 mm per year−1, indicating a continuous positive LOS displacement. This usually points to the slow descent of a stable deforming body or the slow activity of an embedded thrust fault. It may also be related to the combined effect of near-surface subsidence caused by vegetation or permafrost layer degradation.

In the northern margin and the southwestern piedmont area, the pixels are mainly of light green to blue-gray color, with a cumulative displacement of less than ±15 mm. The overall state remains relatively stable. Only local valley slopes show moderate amplitude deformation of 20–40 mm, which is speculated to be related to seasonal freeze–thaw and snowmelt as well as the creep of the slope loose layer.

The red profile (running from northwest to southeast) spans the largest deformation area and can serve as a key monitoring section for the subsequent sequential displacement-velocity profile; the deformation gradient in the northern section of the profile significantly increases, indicating the potential location of the landslide interface or fault zone.

The PS points are densely distributed (>1000 points per square kilometer) and the overall coherence is greater than 0.7, providing high confidence for the deformation conclusion. Overall, it can be seen that: ① The deformation is mainly concentrated in the transition zone between the rock slope surface and the alluvial layer at the bottom of the valley; ② The rate has basically maintained a monotonically increasing trend throughout the monitoring period, without any significant acceleration peaks, and it belongs to a stable creep-type deformation.

3.2. Monitoring and Analysis of Regional Deformation Curves

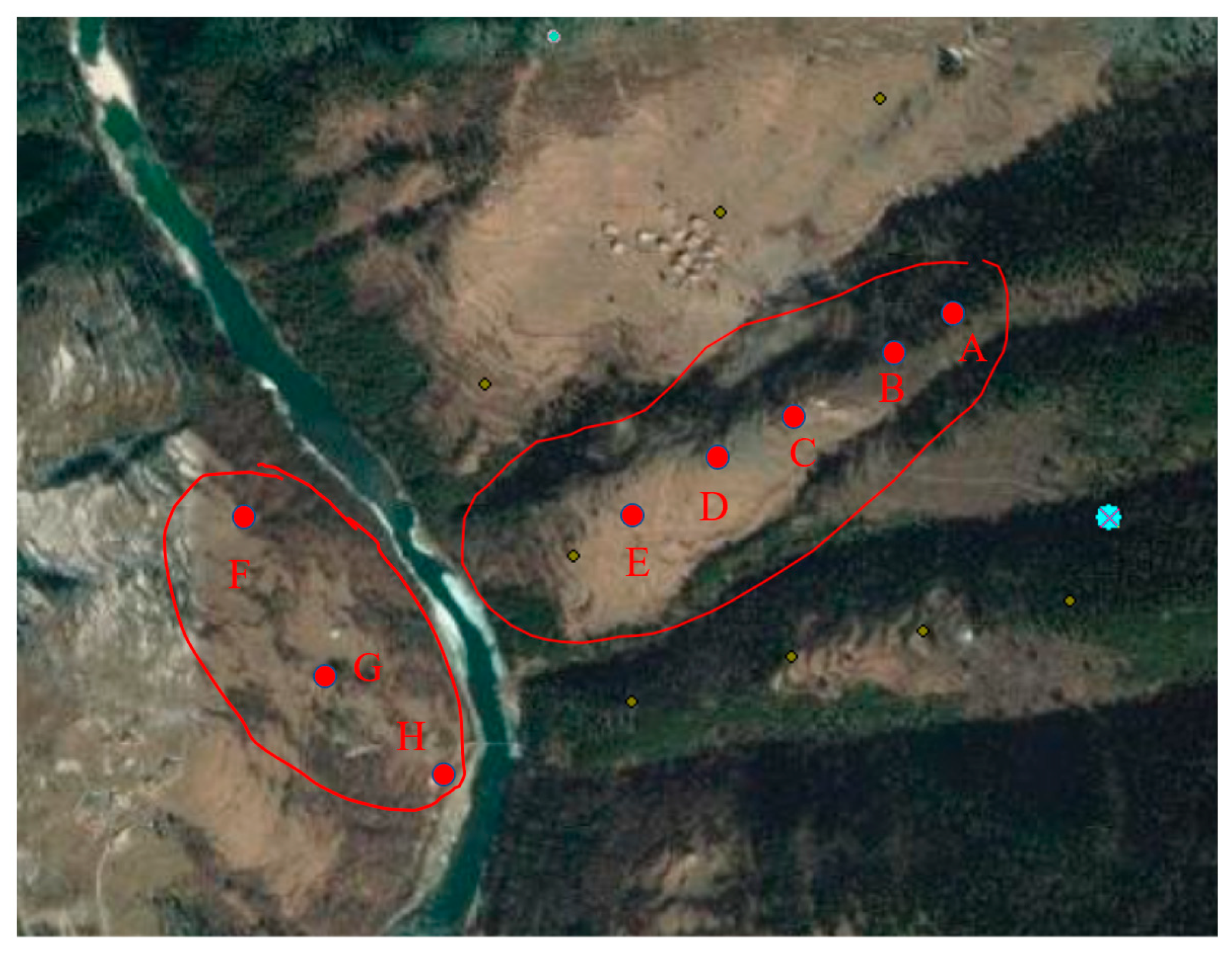

As shown in

Figure 4, eight monitoring points were set on the slope to observe the changes in settlement and displacement from 2021 to 2025 (A–H), thereby analyzing the stability of the surrounding rock of the water-facing slope.

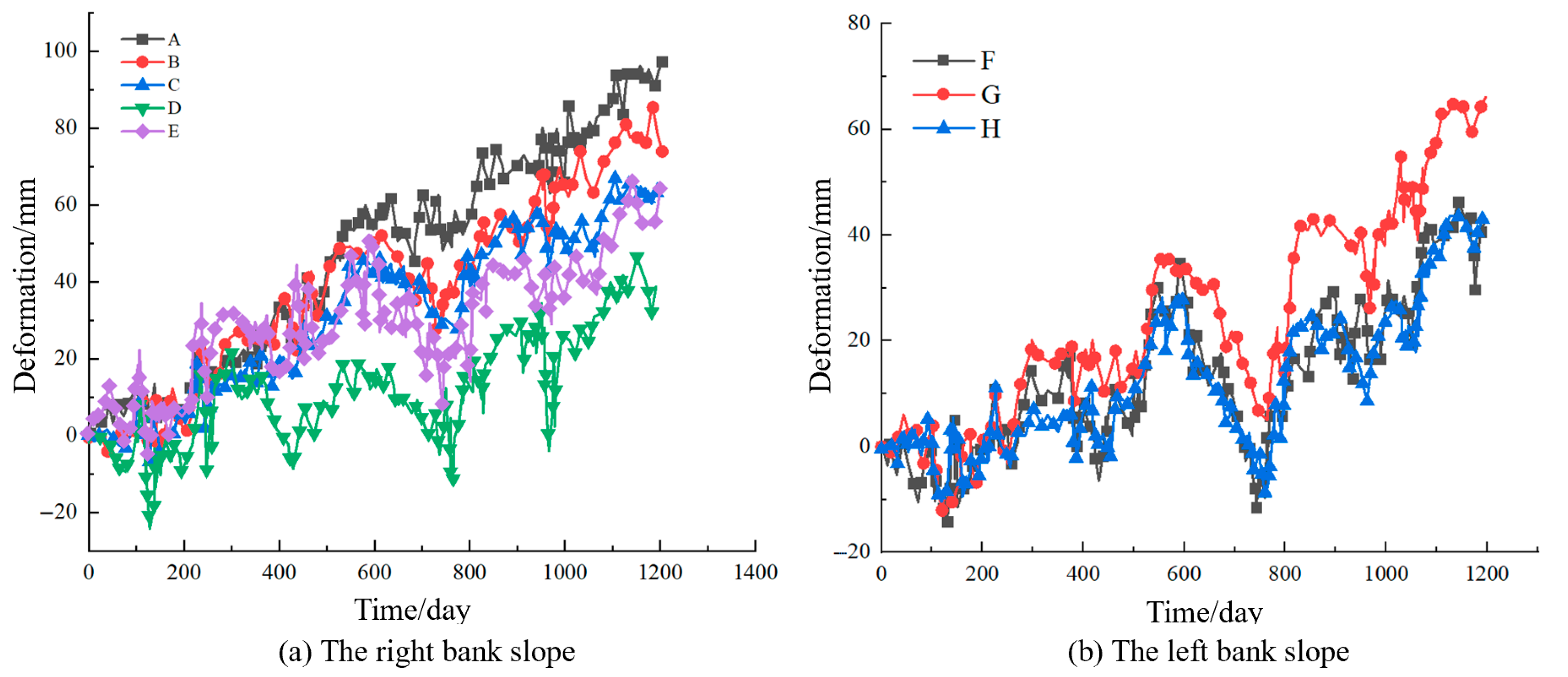

As shown in

Figure 5, the cumulative displacement time series curve of the slope representative points presents a smooth and gradual upward trend. The overall cumulative downward movement along the line of sight is 80 to 100 mm, which is converted to a horizontal displacement of approximately 9 to 11 cm along the slope direction. The deformation magnitude is highly consistent with the typical characteristics of “stable to creep-type” landslides. During the monitoring period, the displacement rate remained within the low-to-medium speed range of 0.2 to 0.8 mm/d. No exponential rate jumps were observed, nor were significant sudden displacement peaks recorded. This indicates that the sliding zone soil is still in the progressive shear stage, and the overall structure still has a certain self-stabilizing ability.

Therefore, it can be determined that the current deformation is mainly controlled by seasonal infiltration softening and self-weight stress adjustment. No continuous sliding surface has yet formed. Although the safety factor has decreased, it is still higher than the critical instability threshold. Based on the above analysis, the probability of overall instability of this slope occurring in the short term is relatively low. Increase the frequency of monitoring during the rainy season, and focus on tracking whether the rate exceeds 1 mm/d or local tensile cracks expand, so as to promptly upgrade the warning level.

4. Numerical Simulation Analysis of Slope Stability

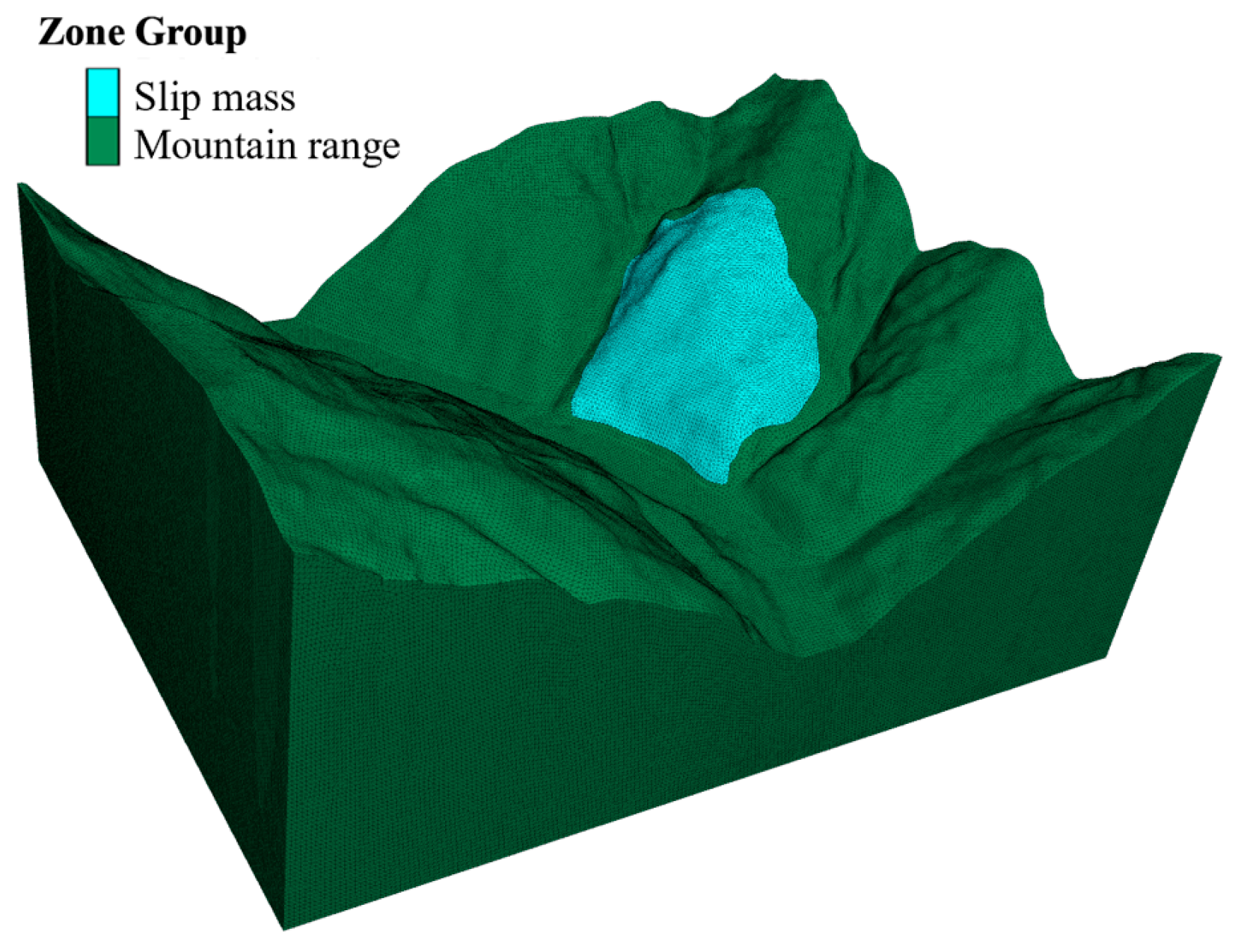

As shown in

Figure 6, the three-dimensional numerical simulation of the slope was conducted using the FLAC3D 9.0 software [

20]. Firstly, the modeling was carried out using the Rhino 7.0 software, which fully included key geological units such as the deformation body, bedrock, weak interface between bedrock and overburden, and the surrounding slope. Then, the meshing was performed, and the meshing was carried out using the “partitioned densification + gradual transition” refined method. Different regions were set with differentiated mesh sizes to balance the calculation accuracy and efficiency: the core research area (the deformation body and the interface between bedrock and overburden area) used structured hexahedral elements, with a uniform mesh size of 5 m, ensuring precise capture of the deformation and stress characteristics of the shear slip zone; the transition area (the stable bedrock area around the deformation body) had a gradually changing mesh size to 10 m, and the mesh size in the model boundary area was further enlarged to 20 m, avoiding the interference of boundary effects on the calculation results. After mesh generation, the mesh quality was verified through the built-in mesh quality check module of FLAC3D, and the distortion rate of the elements was all less than 5%, and the overall mesh quality met the requirements for multi-field coupled numerical simulation. The model exhibits typical mountainous landform features, including steep slopes, valleys, and ridge topography. The blue areas in the figure represent the locations where instability sliding may occur. In the model, these blue areas are set as interface contact surfaces to simulate the shear sliding behavior of the rock mass along weak structural planes. This processing method allows this area to undergo relative sliding and sudden displacement changes under external loads (such as gravity, self-weight, water pressure, etc.), thereby more realistically simulating complex geological processes such as slope instability and landslide evolution.

This model is constructed based on the maximum landslide volume estimation provided by the design unit at the project’s initial stage, under the condition of limited geological exploration data. The landslide volume is approximately 2.1 million cubic meters, which is calculated based on the estimated maximum sliding surface. This volume serves as the reference for the boundary of the sliding body in this simulation, representing the upper limit assessment value of the potential landslide scale under the most unfavorable conditions. During the model construction, the interface contact surface was set based on this sliding assumption, and the slip mechanism and instability discrimination analysis were conducted accordingly. The parameter values are shown in

Table 1.

4.1. Displacement and Deformation Analysis

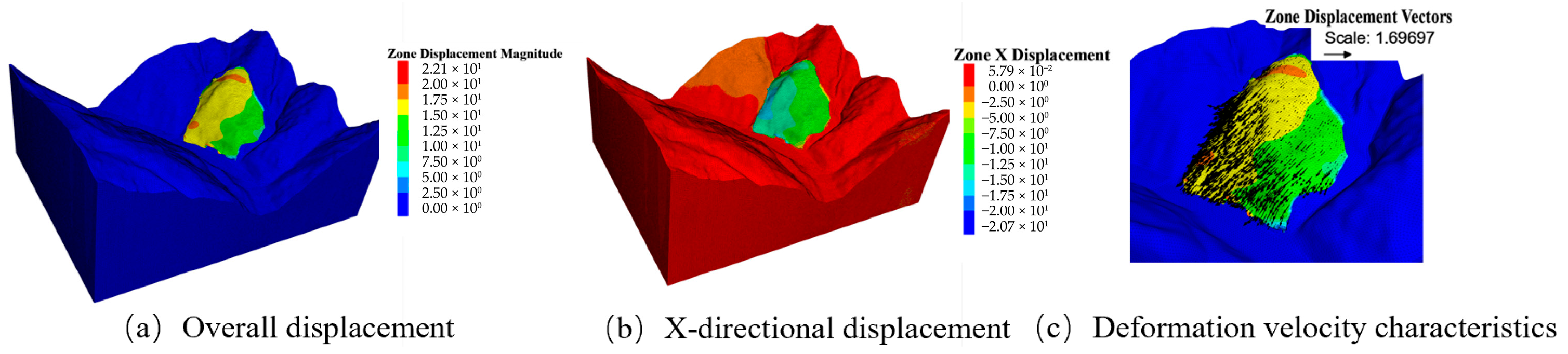

As shown in

Figure 7a,b, based on the numerical calculation results, it can be observed that the deformed body undergoes significant shear slip along the base-cover interface during the loading process, forming a typical forward and downward deformation pattern. From the displacement cloud map, it can be seen that the maximum displacement occurs in the upper part of the deformed body, with a value of 22.1 m (in the red area), indicating that this area is the main control deformation zone. The displacement field exhibits a typical “upper tension, lower shear” characteristic. The displacement isosurfaces gradually expand from light blue to green, yellow, and finally to red within the deformed body, with a significant deformation gradient, indicating that there is a clear plastic slip zone in the deformed body, and the deformation is concentrated within the control range of the shallow structural plane. Overall, the landslide belongs to an “overall sliding type” instability process. The failure surface penetrates through the weak interlayers, showing a “shallow layer shear + local tension” composite mechanism. The displacement distribution is symmetrical and has a strong structural control feature.

As shown in

Figure 7c, the maximum deformation velocity occurs in the lower toe area of the deformed body, which is the “outflow” position of the deformed body in the river mouth section. This velocity value indicates that there is a significant “sliding impact effect” during the instability process of the deformed body. The overall risk of entering the river is relatively low: although the velocity is the highest in the bottom river entry section, due to the lagging response of the upper deformed body, no coordinated acceleration mechanism for overall failure was formed. Therefore, it is judged that this landslide tends to be a local acceleration-splintering type landslide at the end of the movement rather than the “overall type of sliding into the river” collapse mode.

4.2. Stress Structural Analysis

As shown in

Figure 8, from the stress cloud diagram, it can be clearly observed that the maximum stress concentration occurs in the upper-middle part of the deformed body. The stress value in this area is significantly higher than that of the surrounding rock, indicating a clear phenomenon of stress concentration. At the same time, multiple approximately parallel plastic slip bands appeared inside the deformed body. These slip bands are distributed in a band-like pattern, indicating that the slope underwent significant plastic deformation during the force application process.

The appearance of the slip zone is usually closely related to the internal slip movement of the surrounding rock, and it is an important indicator of plastic flow in the surrounding rock after exceeding the yield limit. Further analysis reveals that the orientation of the slip zone is basically consistent with the direction of the maximum shear stress, indicating that the deformation is mainly driven by shear stress. In addition, the stress in the slip zone area is relatively high, and local stress concentration may lead to the emergence of cracks, thereby affecting the overall mechanical properties of the surrounding rock and the stability of the slope.

5. Simulation of 2.1 Million Cubic Meters of Deformable Body Swells

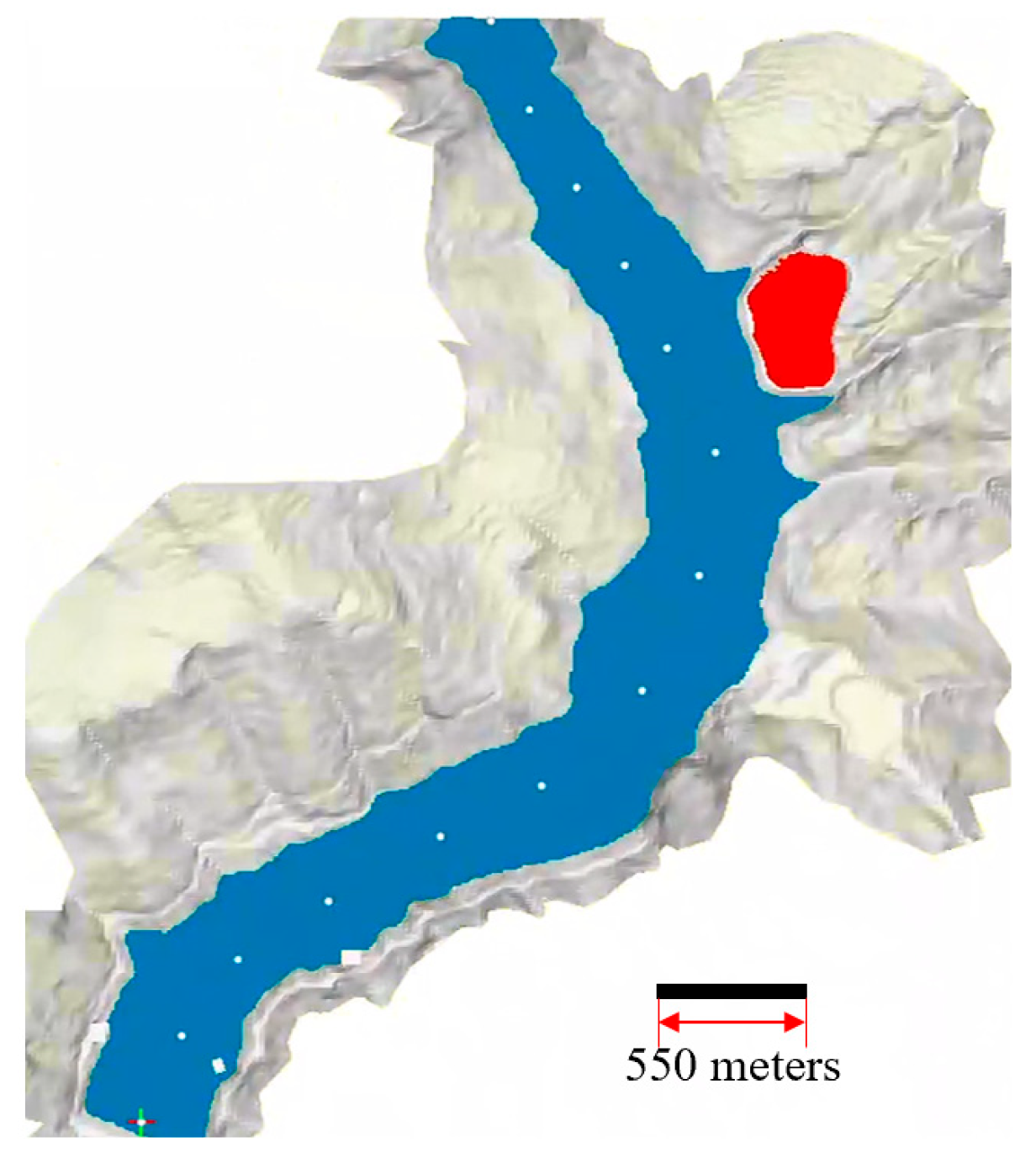

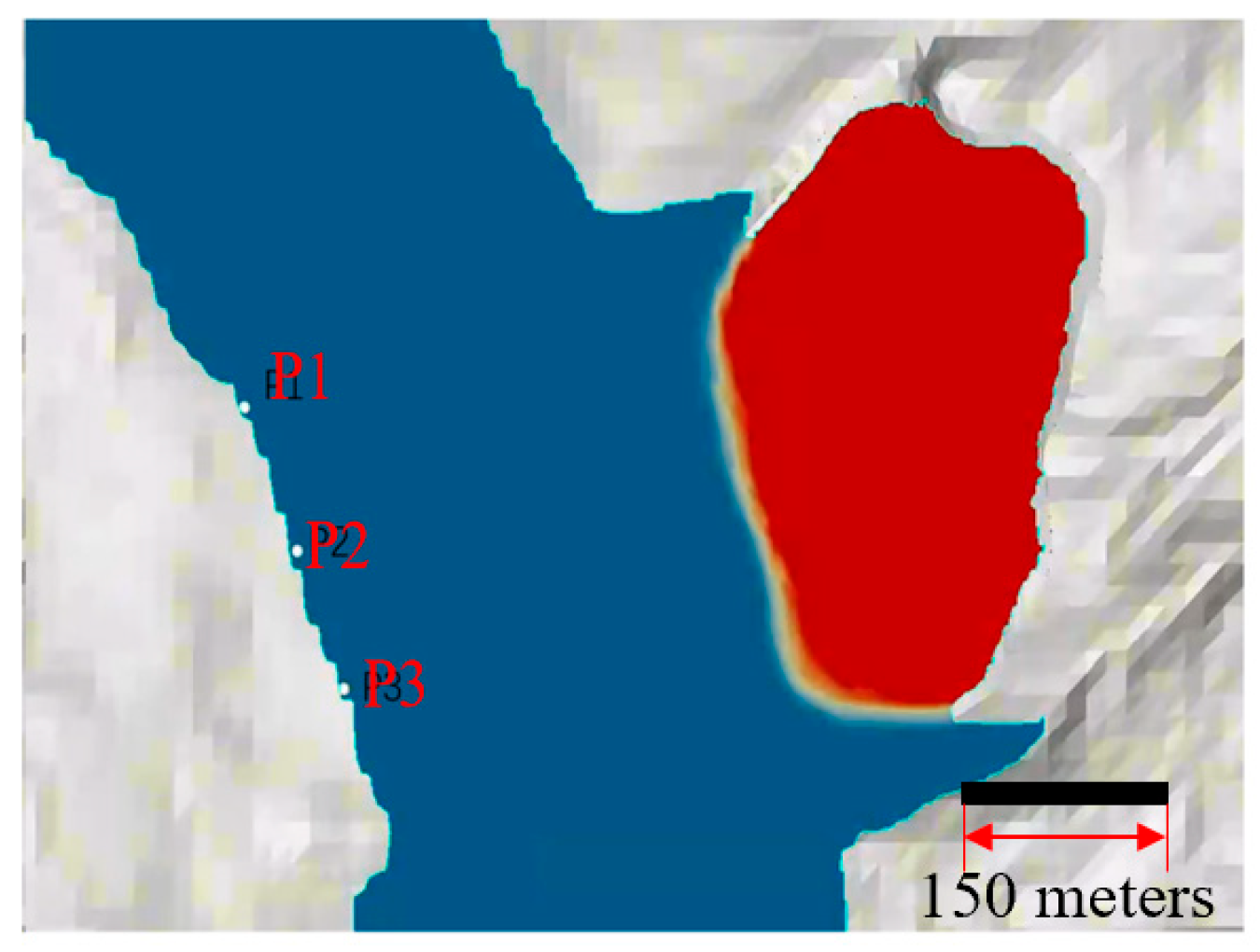

Figure 9 illustrates the overall computational model for simulating the waves caused by landslides using the FLOW-3D simulation software [

21]. This model is based on the measured terrain data and reconstructs the three-dimensional terrain and water distribution of the deformed body before and after it enters the water. The blue area represents the reservoir water body, the surrounding light gray area represents the terrain and topography of the two banks, and the red area in the upper right corner is the assumed position of the deformed body, simulating its instability and water entry process as well as the wave propagation effect caused by it. The model also sets up multiple monitoring points (marked in white) to record key physical quantities such as wave height and water level changes, providing basic data support for the subsequent analysis of wave propagation laws. The overall model construction fully considers the complexity of the terrain and the geometric characteristics of the deformed body, and has a good degree of terrain restoration and physical authenticity.

5.1. The Characteristics of Waves at Different Times

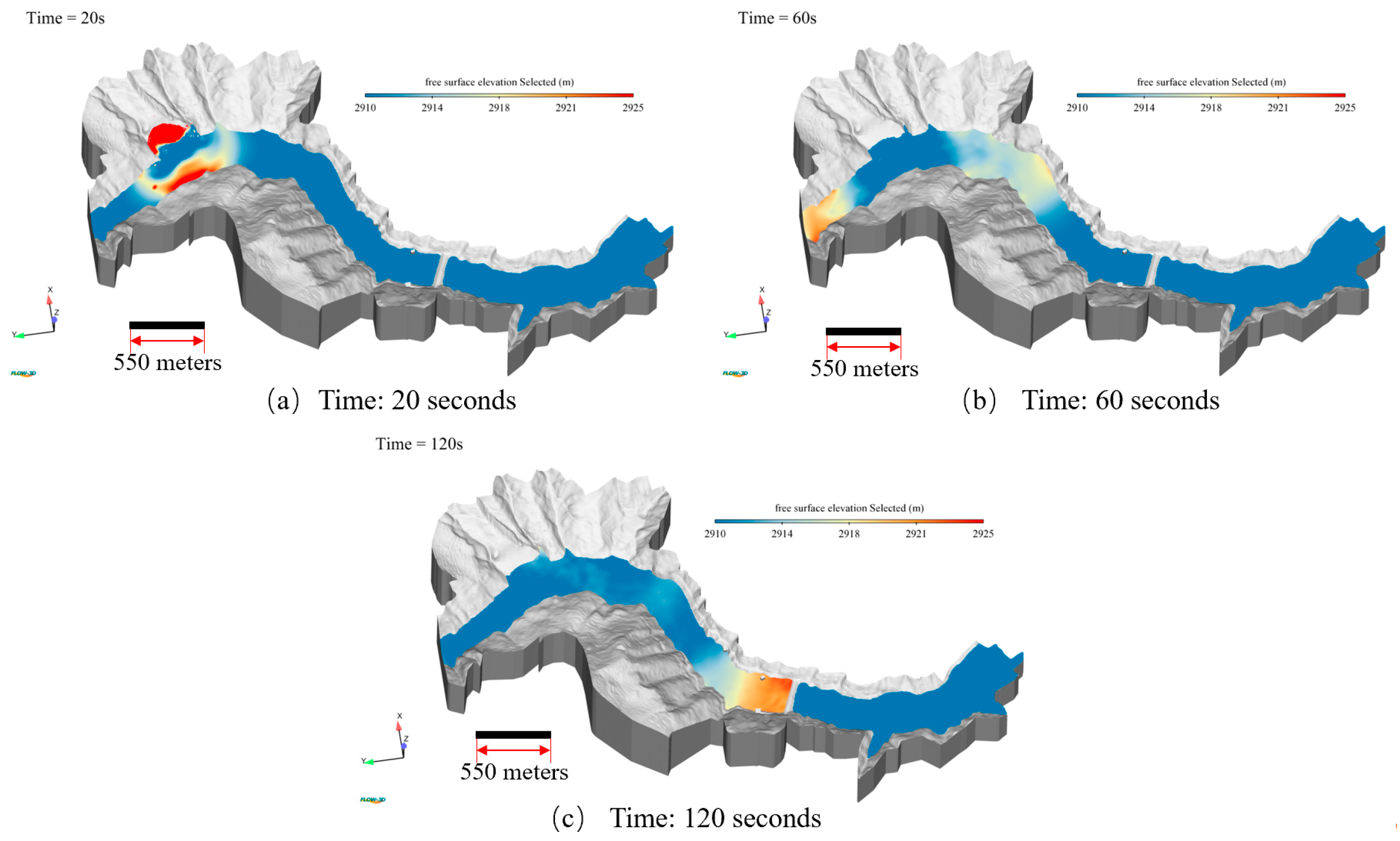

To investigate the disturbance effect of large-scale deformable bodies on the water body in the reservoir area under the condition of medium-high speed water entry, the volume of the deformable body was set at 2.1 million cubic meters, the initial sliding speed was 24 m/s, and the initial water surface elevation was 2910 m. The free liquid surface distribution situations at three critical moments of 20 s, 60 s, and 120 s were compared and analyzed, as shown in

Figure 10.

Time = 20 s: At the moment when the deformed object rushes into the water body at high speed, the huge kinetic energy is rapidly converted into water dynamic potential energy, forming a highly impactful main surging wave at the point of entry. This main surging wave is like a surging white water wall, spreading rapidly along the preset advancing direction, causing intense disturbance to the water surface in the reservoir area. The water surface in the entry area shows a state of turbulent boiling, with a large amount of water splashing, while the still water area on the opposite bank is also affected by this powerful energy wave, and the originally stable water surface instantly breaks apart, forming chaotic ripples and local vortices. Through the elevation monitoring data, it can be seen that the height of the main wave peak marked in the red highlighted area has exceeded 2925 m, which is a significant 15 m higher than the initial still water level. Such a remarkable water level increase is released in a short period of time. At the same time, the distance between the wave peak and trough of the main surging wave is extremely short, and the energy density is highly concentrated. When it impacts the reservoir bank, it produces a dull rumbling sound, fully demonstrating the typical characteristics of a violent impact, posing an immediate threat to the geological structure and protective facilities in the nearshore shallow water area.

Time = 60 s: As the main swells continued to advance along the reservoir channel, their energy began to gradually radiate outward. The central part of the reservoir, as the key area for wave propagation, exhibited a clear fluctuation response, with the water surface showing a regular undulating state. Since the reservoir’s shoreline was not absolutely smooth, the waves encountered multiple reflections and diffractions with the reservoir banks during their propagation, and the reflected waves and the incident waves superimposed each other, forming multiple secondary wave groups, making the water surface fluctuation pattern more complex. The water levels on both sides of the bank areas showed a distinct alternating rise and fall trend, with the maximum and minimum water levels differing by 3–5 m. This phenomenon indicates that the current fluctuations already possess significant nonlinear characteristics, and the wave energy can propagate in multiple directions, breaking the initial single-directional propagation mode. It is worth noting that some wave energy has successfully spread across the width of the reservoir to the opposite bank, and the water level on the opposite bank also shows periodic rises and falls. The entire reservoir enters a dynamic equilibrium stage of full fluctuations.

Time = 120 s: After two minutes of propagation, the main wave peak successfully reached the area in front of the dam downstream of the reservoir, causing a significant rise in the water level in front of the dam. The measured data shows that the water elevation in some areas has approached 2923 m, which is only 2 m lower than the initial main wave peak. This data fully proves that the waves still maintain a strong energy reserve capacity during long-distance propagation. Different from the sharp wave shape in the initial propagation stage, the wave shape in front of the dam becomes thicker and more blunt, with a significantly increased wave peak width, and the impact range covers the entire water area in front of the dam. This thick and blunt wave shape has a larger impact width and a longer duration, and is no longer a transient impact but transforms into a periodic dynamic load on the dam structure. This periodic load will continuously act on the dam’s dam surface, foundation, and seepage prevention system. In the long term, it may have potential impacts on the stability of the dam structure, and further monitoring and calculation are needed to assess the specific threat level to the dam’s safety.

5.2. The Impact of the Deformed Body on the Opposite Bank

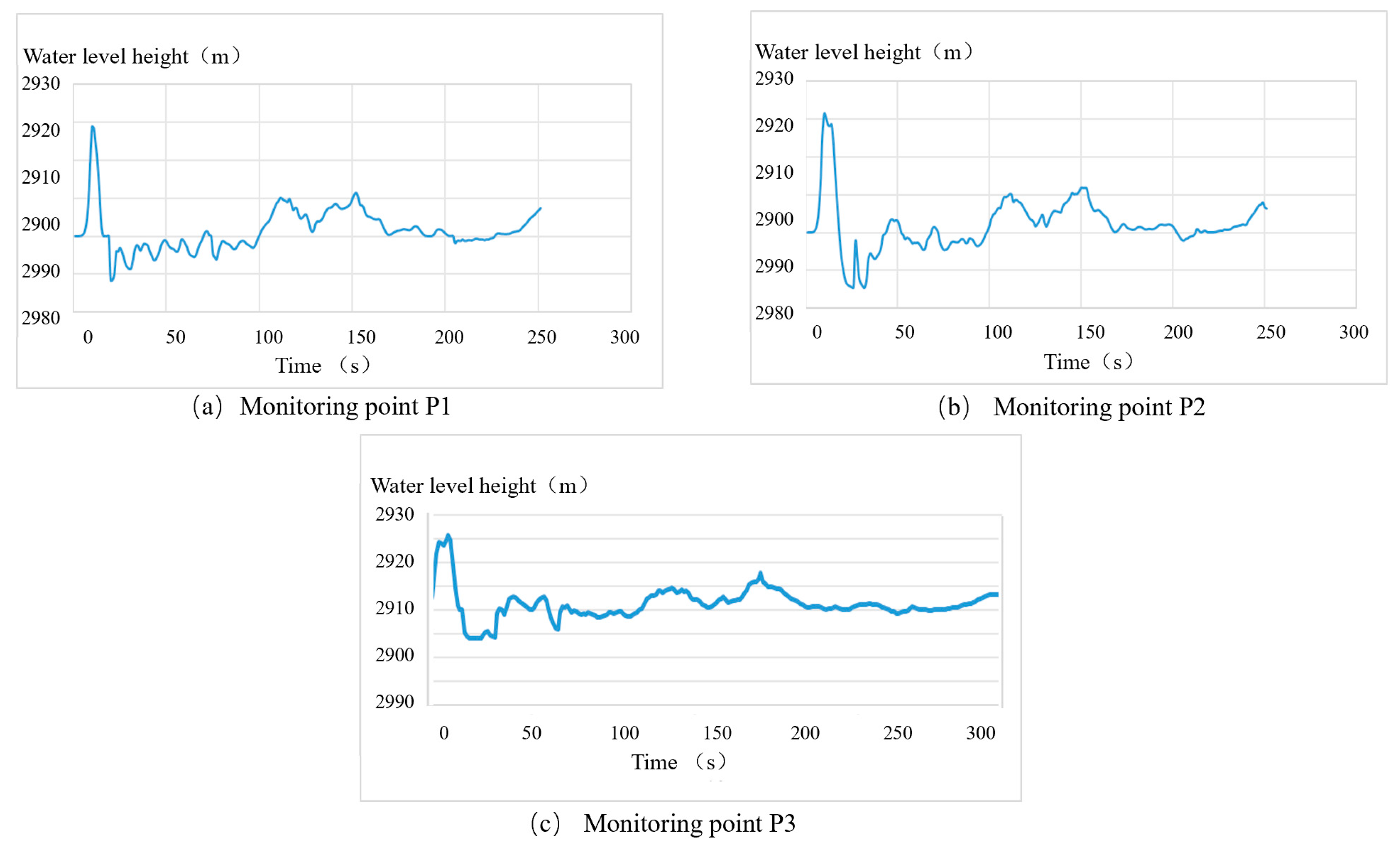

To study the impact effect of the waves generated by the deformation body entering the water on the opposite shore area, monitoring points P1, P2, and P3 were set up directly opposite the deformation body. The time series changes in the free liquid surface were extracted to analyze the propagation characteristics of the waves and the response patterns of the shore slope, as shown in

Figure 11.

As shown in

Figure 12, the three monitoring points simultaneously captured the first main wave response approximately 10 s after the deformation body entered the water. The curve rose sharply and then dropped sharply, exhibiting typical characteristics of an impact-type surf wave: the wave peak was high, the leading edge was almost vertical, and then the water level dropped sharply. The maximum peak exceeded 2925 m, which was more than 15 m higher than the still water level, with concentrated energy and a short duration, highlighting the “short-term high impact” attribute.

This phenomenon indicates that when the landslide body enters the water at high speed, it triggers a strong initial surging wave. The wave crest rushes directly towards the bank slope along an approximately ballistic trajectory, causing a frontal impact. The instantaneous dynamic pressure can reach several hundred kilopascals, which is prone to causing erosion and cavitation damage to the slope foot protection structures. At the same time, the water level rises sharply and then rapidly drops, generating intense negative pressure suction, further weakening the strength of the rock and soil. The peak heights at the three measurement points are consistent, and the time difference is less than 1 s. This reflects that the surging wave propagates extremely fast, with the near-field wave front approximately flat, and the impact effect is highly synchronous. This provides key boundary conditions for subsequent slope stability evaluation and design of breakwater walls.

6. Results and Discussion

This paper conducts a systematic study on the deformation development and stability analysis of the Sejiang deformation body at the Baala Hydroelectric Power Station, as well as the possible response of tsunamis it may trigger. It comprehensively employs three key technical means: PS-InSAR remote sensing monitoring, FLAC3D stability simulation, and FLOW-3D surge calculation. A complete analysis system of “macroscopic deformation identification-local instability mechanism analysis-quantification of landslide secondary disasters” is constructed, achieving multi-level and full-chain quantitative assessment. The research strictly follows relevant industry regulatory standards, clearly distinguishes the attributes of various parameter assumptions, and fully considers the uncertainty factors in the research process. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) The deformation area is in a long-term stable-rhythmic evolution state, and no recent sudden large deformation has occurred. The time-series inversion results based on PS-InSAR data indicate that multiple deformable bodies and their adjacent slopes in the study area have been in a slow deformation state of 10–25 mm/a for a long time, showing obvious “step-like” and “seasonal fluctuation” characteristics, and belong to the typical “stable-rhythmic landslide”. The spatial distribution of deformation shows a significant NW-SE band-like difference, with the core deformation area concentrated in the central-southern part. The annual average deformation rate is approximately 12–26 mm/year, presenting a continuous positive displacement; while the northern edge and the southwestern foothill area are mainly dominated by light green to blue-gray pixels, with cumulative displacement less than ±15 mm, and overall in a stable state, with only local gully slopes having medium-amplitude deformation of 20–40 mm. The density of PS points within the monitoring area is high, exceeding 1000 per square kilometer, with an overall coherence greater than 0.7, providing high credibility data support for deformation analysis.

(2) Through numerical simulation, it can be seen that the deformable body mainly undergoes shear slip along the base-cover interface, presenting a typical structural failure mode of “upper tension-lower shear”. The deformation curve shows a nonlinear evolution process of “initially slow-mid-term acceleration-final sudden change”. After the deformable body enters the water, it causes strong free water surface disturbance, forming high-amplitude swells. When a 210 million cubic meter deformable body enters the water at a speed of 24 m/s, the maximum water level at the opposite bank and the dam is approximately 2925 m, which is close to the top elevation of the dam but within the engineering safety limit.

The integrated technical route of “monitoring-simulation-risk assessment” adopted in this study has achieved a full-chain analysis from macroscopic deformation identification to microscopic mechanical mechanisms, and to the impact of secondary disasters. It provides a reliable paradigm for the stability research of slopes near water. However, the research still has certain limitations. The PS-InSAR monitoring is difficult to completely avoid the influence of atmospheric phase errors. In the numerical simulation, the selection of geological parameters is based on limited survey data, and the consideration of the spatial heterogeneity of rock and soil parameters is not comprehensive enough. In the future, combined with means such as drone aerial photography and on-site drilling and sampling, the monitoring accuracy and model parameters can be further optimized. At the same time, multi-condition simulations with different deformation volumes and different water entry speeds can be carried out to improve the slope disaster risk assessment system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.L. and G.L.; methodology, G.L.; software, G.L.; validation, D.L.; formal analysis, B.J.; investigation, B.J.; resources, D.L.; data curation, G.L.; writing—original draft preparation, D.L.; writing—review and editing, D.L.; visualization, C.Z.; supervision, G.L.; project administration, D.L.; funding acquisition, G.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This thesis expresses its gratitude to the financial support provided by the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LQ24D020001), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52304092), Opening fund of State Key Laboratory of Geohazard Prevention and Geoenvironment Protection (Chengdu University of Technology SKLGP2024K014).

Data Availability Statement

Some or all data, models, or code generated or used during the study are available from the corresponding author by request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors Dongqiang Li, Baodong Jiang employed by China Water Resources and Hydropower Tenth Engineering Bureau Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Sun, S.G.; Shao, S.S.; Jiang, J.; Quan, J.Y. Influence of combined method of opencast and underground mining on slope stability. Min. Metall. Eng. 2020, 40, 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.J.; Li, Y.; Yin, J.B.; Yang, F.; Tao, Z.G. Influence of Joints and Fissures on the Stability of Steep Slopes in Open-pit Stopes. Met. Mine 2023, 10, 196–204. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, H.; Lu, A.-Z.; Ma, Y.-C.; Yin, C.-L. Semi-analytical solution for stress and displacement of lined circular tunnel at shallow depths. Appl. Math. Model. 2021, 100, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Li, L.; Chen, G.; Liu, H.; Ji, X.; Jiang, X.; Zhou, S. An improved 3D DDA method considering the unloading effect of tunnel excavation and its application. Comput. Geotech. 2023, 154, 105178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Liu, H.; Li, L.; Wang, X.; Tu, W.; Gao, J.; Yang, G. Weakening mechanism of shear strength of jointed rock mass considering the flling characteristics. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2024, 83, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Li, L.; Zong, P.; Liu, H.; Yang, L.; Wang, J.; Yan, P.; Sun, S. Advanced stability analysis method for the tunnel face in jointed rock mass based on DFN-DEM. Undergr. Space 2023, 13, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.Q.; Jiang, L.W.; Mu, Y.C.; Li, X.; Wang, S.D.; Zhao, S.W.; Wang, G.Q.; Yin, X.K. Advanced Geological Forecasting Techniques for Railway Tunnels in the Complex and Treacherous Mountainous Areas of Southwest China. Mod. Tunneling Technol. 2024, 61, 52–59. [Google Scholar]

- Rodsin, K.; Ejaz, A.; Hussain, Q.; Suthasupradit, S.; Parichatprecha, R.; Shrestha, K. Low-Cost Glass Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composite Wraps for Strengthening Deep Beams with and without Longitudinal Openings. Eng. Sci. 2025, 36, 1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teltayev, B.B.; Muta, A.N. Assessment of the Stability of the Slope of Kok Tobe Mountain. Eng. Sci. 2025, 35, 1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, C.C.; Pang, S.H.; Du, Y.G.; Qiao, X.B.; Tao, Z.G. Study on engineering geological zoning and stability evaluation of the open-pit copper mine slope. J. Henan Univ. Technol. (Nat. Sci.) 2022, 41, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, J.; Huo, Z.G.; Li, H.Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.F. Seepage sliding analysis and stability study of sub-horizontal slope under fissure water. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 2022, 3, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, C.; Li, Z.; Wu, J.; Wang, R.; Yang, X.; Liu, Y. Research on double.layer support control for large deformation of weak surrounding rock in xiejiapo tunnel. Buildings 2024, 14, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Deng, B.; Zhang, D.; Li, M.; Song, Z. Influence of weak interlayer thickness on mechanical response and failure behavior of rock under true triaxial stress condition. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 162, 108419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Xing, X.; He, M.; Tang, Z.; Xiong, F.; Ye, Z.; Xu, C. Failure behavior and strength model of blocky rock mass with and without rockbolts. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2024, 34, 747–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinthong, S.; Ditthakit, P.; Salaeh, N.; Wipulanusat, W.; Weesakul, U.; Elkhrachy, I.; Yadav, K.K.; Kushwaha, N.L. Combining Long Short-Term Memory and Genetic Programming for Monthly Rainfall Downscaling in Southern Thailand’s Thale Sap Songkhla River Basin. Eng. Sci. 2024, 28, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Huang, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Zheng, H.; Liu, X. The collapse deformation control of granite residual soil in tunnel surrounding rock: A case study. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2024, 28, 2034–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Cui, Y.; Yang, X.; Ma, M.; Li, L. The contact loads inversion between surrounding rock and primary support based on dynamic deformation curve of a deep-buried tunnel with flexible primary support inconsideration. Geomech. Eng. 2024, 36, 575–587. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, K.; Chen, M.; Hu, Y.; Yang, G.; Wen, S.; Yang, K. Theoretical and numerical investigations of blasting influence range of advanced consolidation grouted rock mass on an underground tunnel. Int. J. Geomech. 2024, 24, 4023247.1–4023247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.-S.; Chen, B.-R.; Jiang, Q.; Xu, D.-P.; He, B.-G.; Duan, S.-Q. In-situ comprehensive investigation of deformation mechanism of the rock mass with weak interlayer zone in the Baihetan hydropower station. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, 148, 105690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Jia, J.; Bao, X.; Mei, G.; Zhang, L.; Tu, B. Investigation of dynamic responses of slopes in various anchor cable failure modes. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2025, 188, 109077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabeti, R.; Heidarzadeh, M.; Romano, A.; Ojeda, G.B.; Lara, J.L. Three-Dimensional Simulations of Subaerial Landslide-Generated Waves: Comparing OpenFOAM and FLOW-3D HYDRO Models. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2024, 181, 1075–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).