Optimization of the Prestress Value for Multi-Row Anchor in Anti-Slide Pile Based on a Staged Orthogonal Design

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Computation Theory of FLAC3D 9.0

2.2. Bending Moments for Solid Elements in FLAC3D 9.0

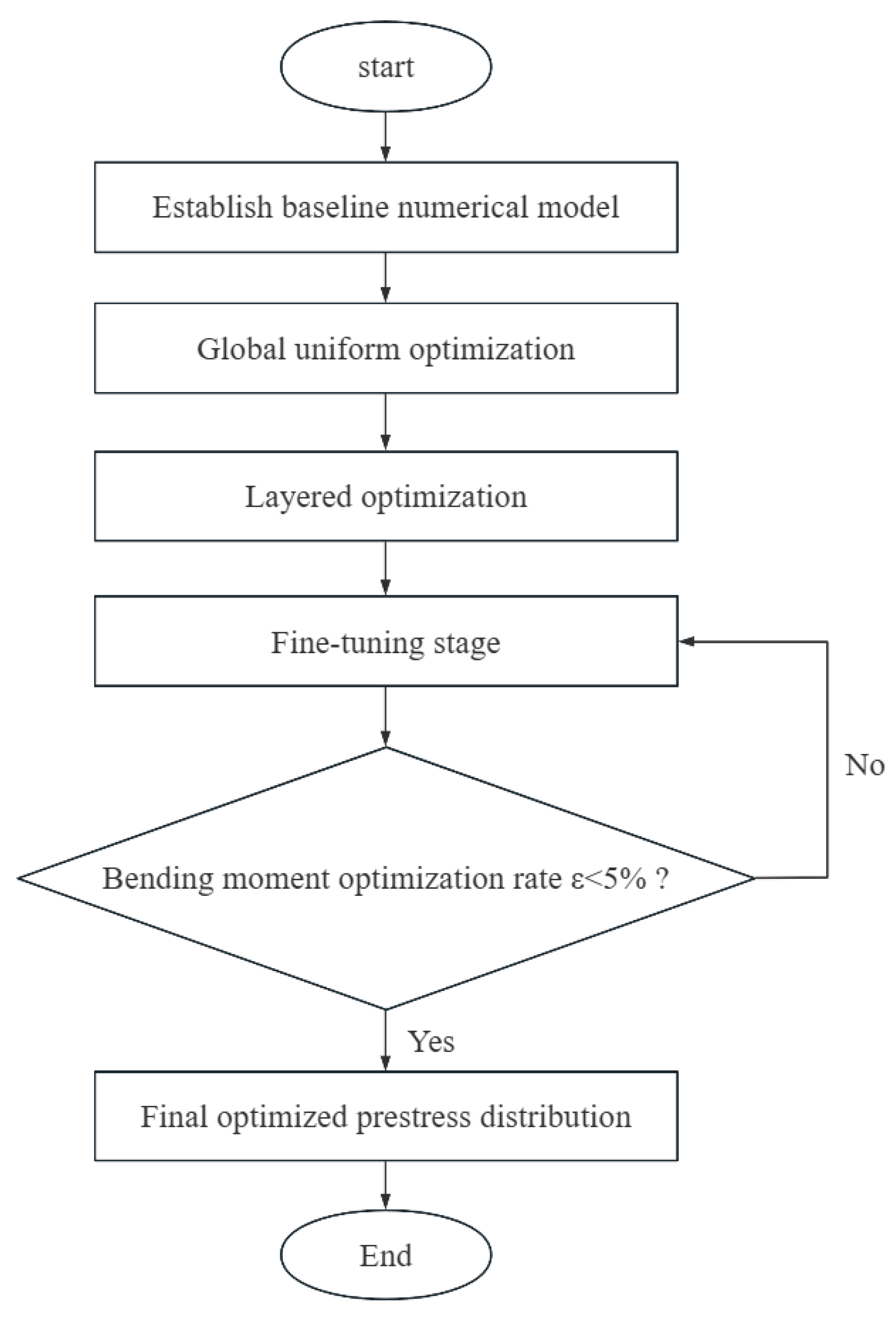

2.3. Optimization Method

- (1)

- Build the three-dimensional FLAC3D 9.0 model of the soil–pile–anchor system using the design geotechnical parameters and boundary conditions.

- (2)

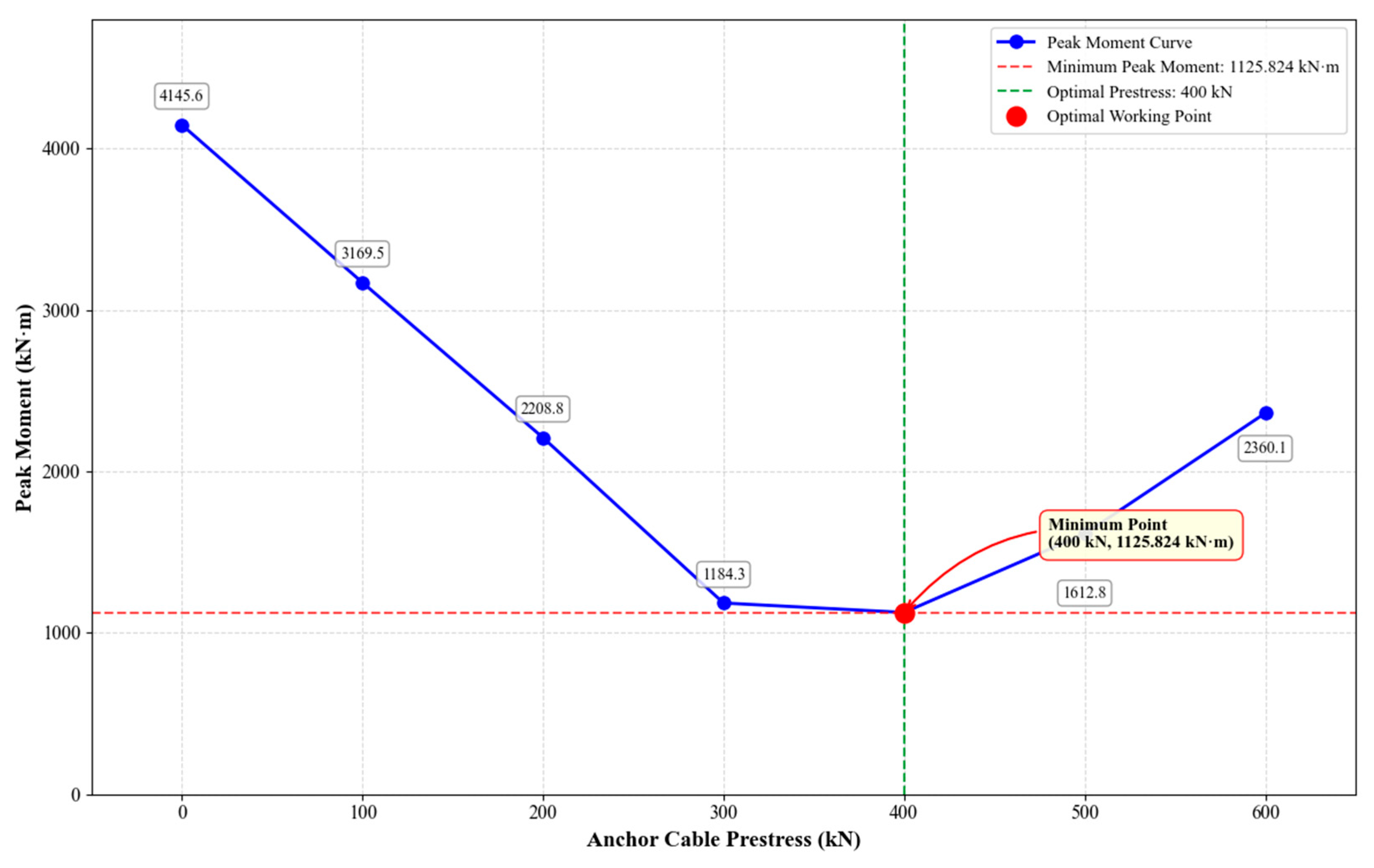

- Stage I (global baseline search): apply a set of uniformly increasing prestress levels to all anchor rows, run FLAC3D 9.0 for each level, and compute the corresponding peak bending moment . Select the baseline prestress that minimizes .

- (3)

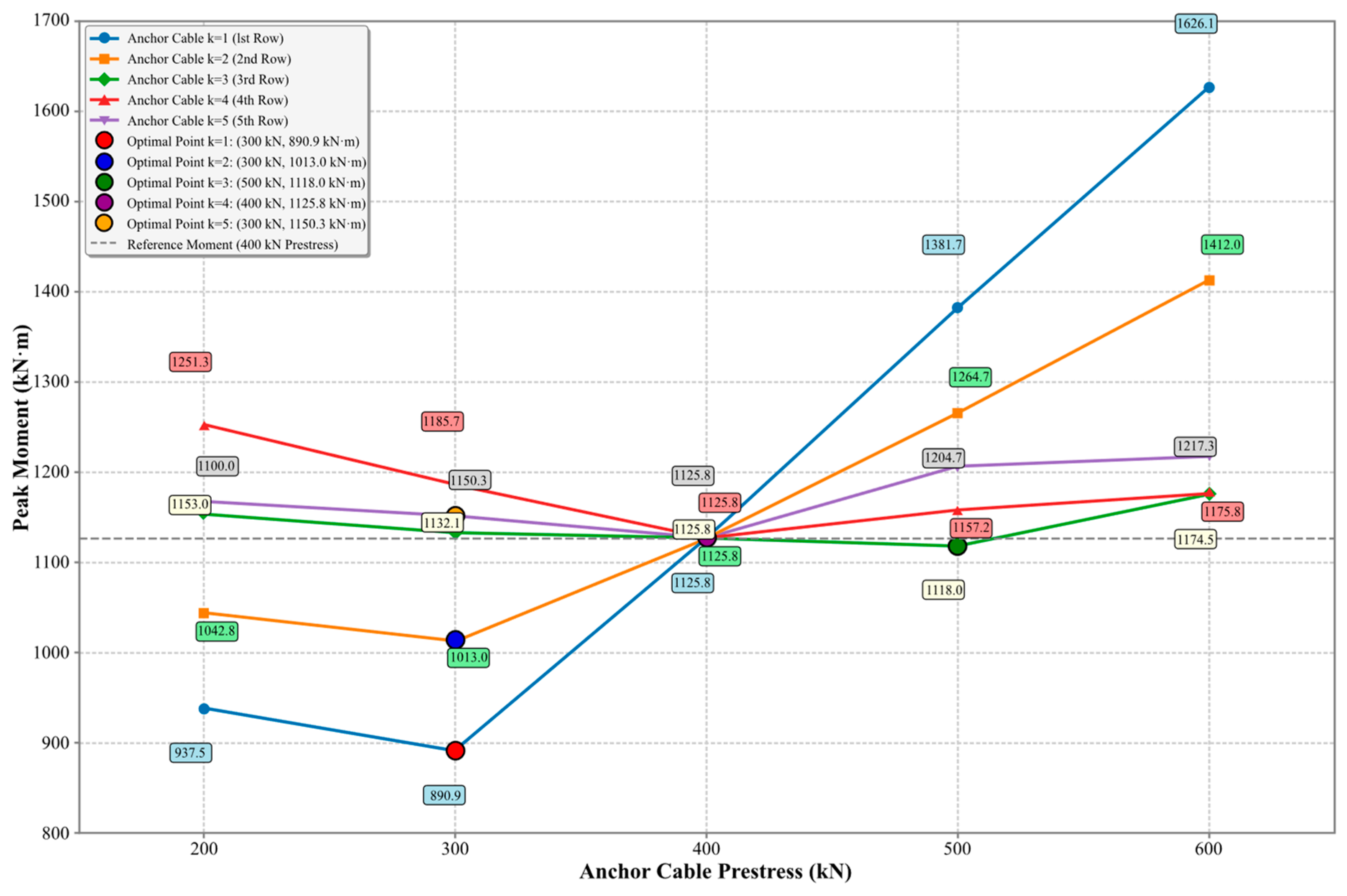

- Stage II (row-wise staged orthogonal design): for each anchor row in turn, vary the prestress of row around over a discrete set of candidate values while keeping the other rows fixed at , and determine the optimal prestress that minimizes the peak bending moment. Assemble the row-wise optimal vector .

- (4)

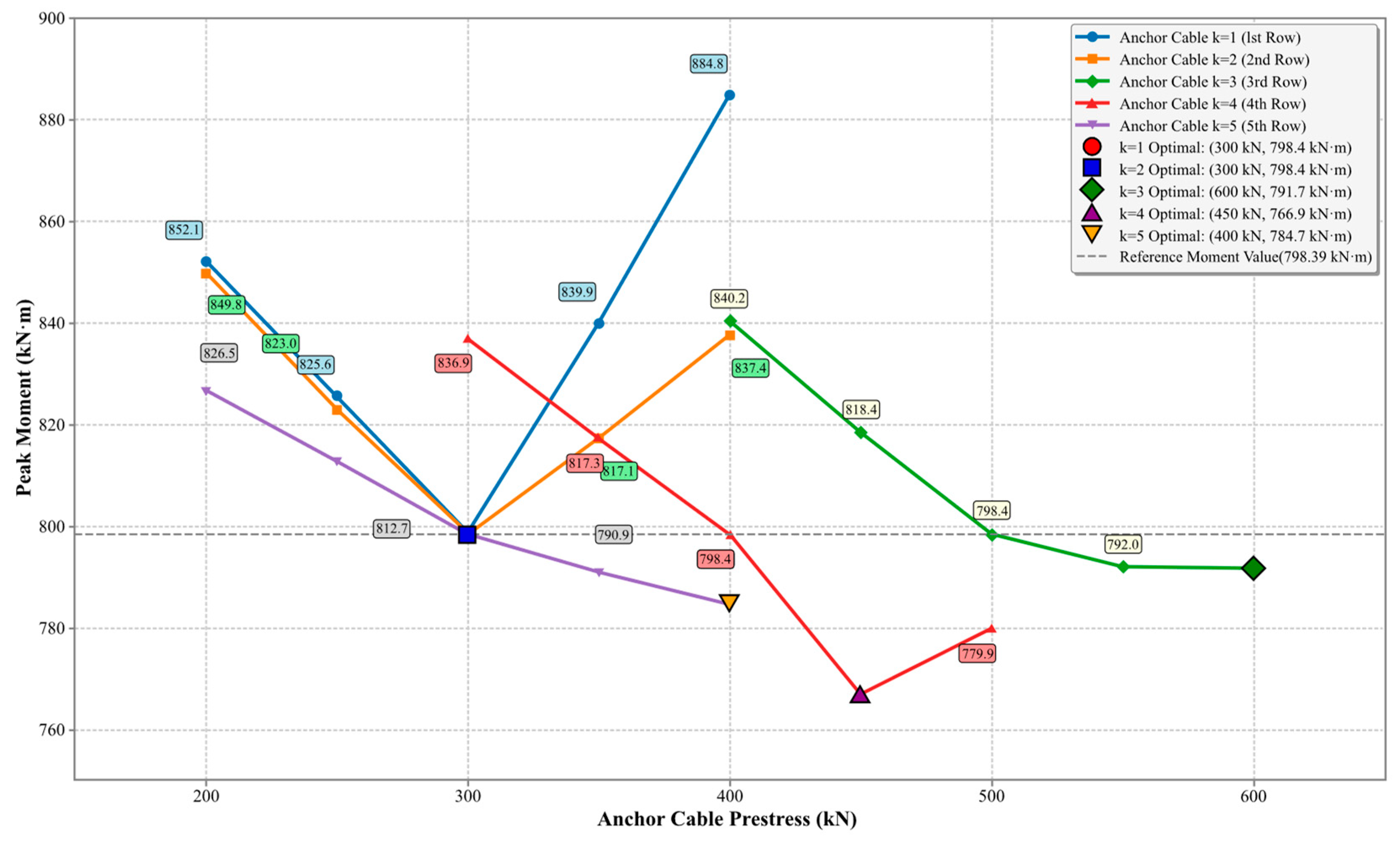

- Stage III (dynamic contraction search): starting from , define a search interval around each and perform a coordinated contraction search over all rows. At each iteration , update the prestress vector, re-evaluate the peak bending moment, and compute the relative improvement .

- (5)

- Check convergence: if < or the iteration count reaches , accept the current prestress vector as the final solution; otherwise, shrink the search intervals and return to step (4).

- (6)

- Output the optimized prestress distribution for all anchor rows and evaluate the final displacement and bending-moment responses of the support system.

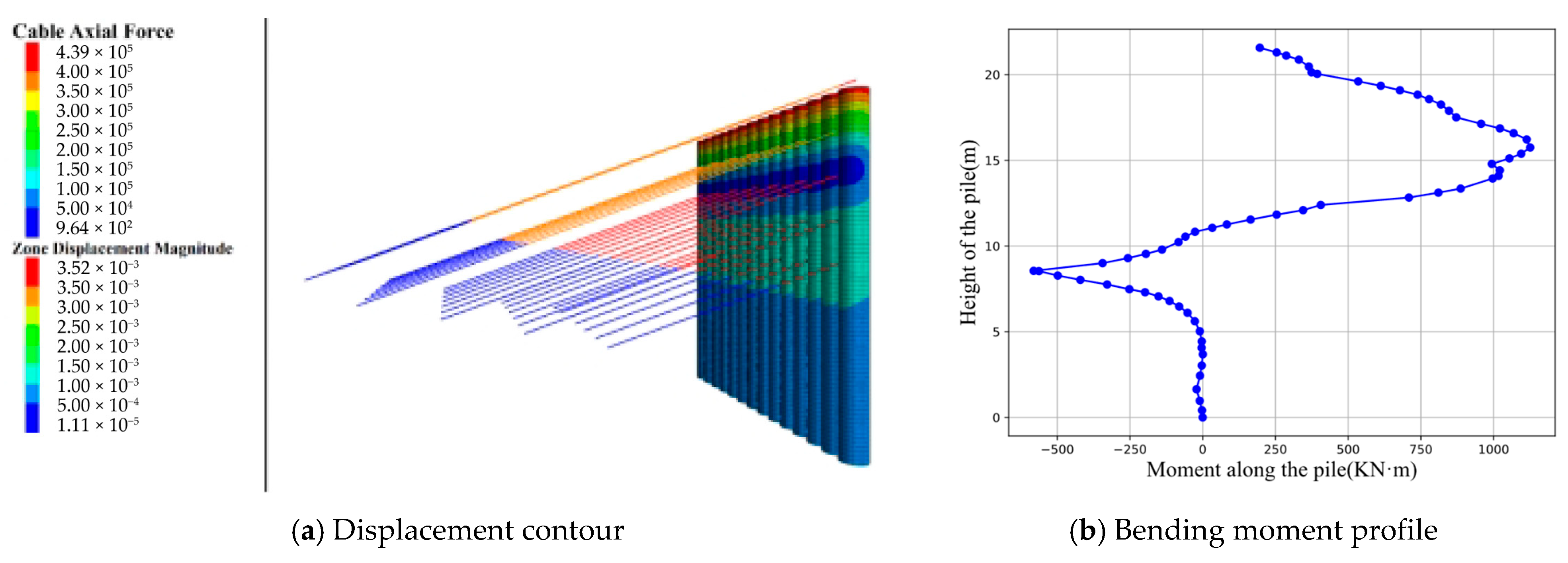

3. Stability Analysis of Geotechnical Structures Based on FLAC3D 9.0

3.1. Project Overview

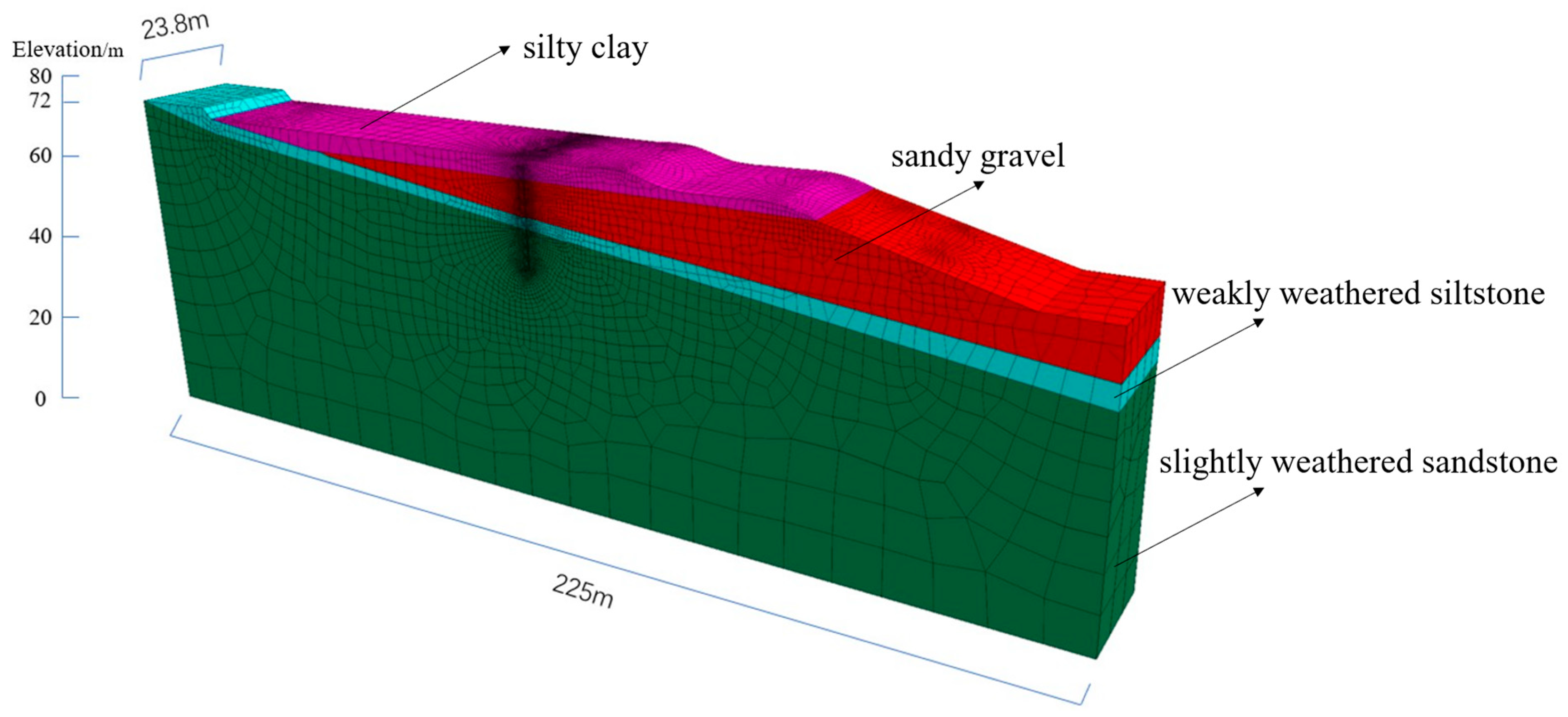

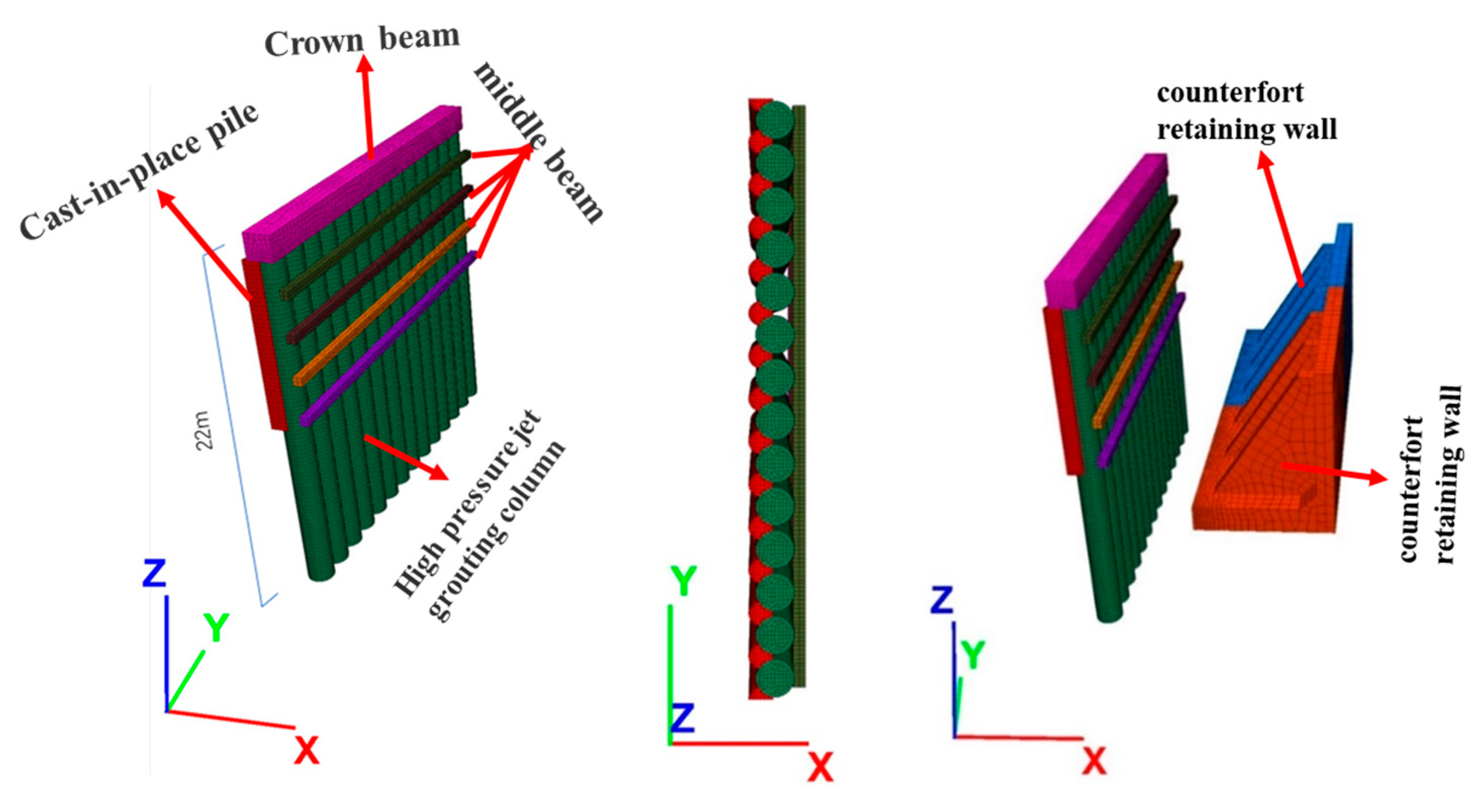

3.2. Numerical Model

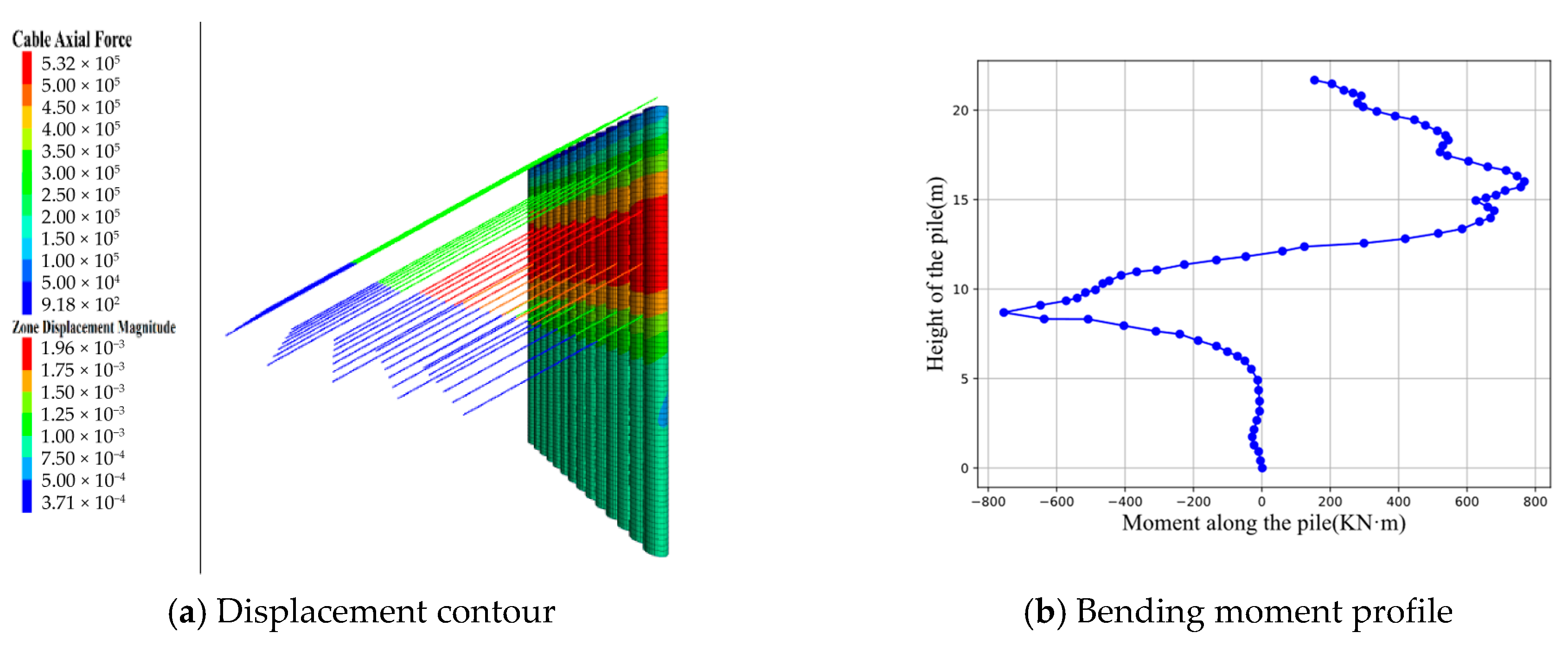

3.3. Parameter Settings

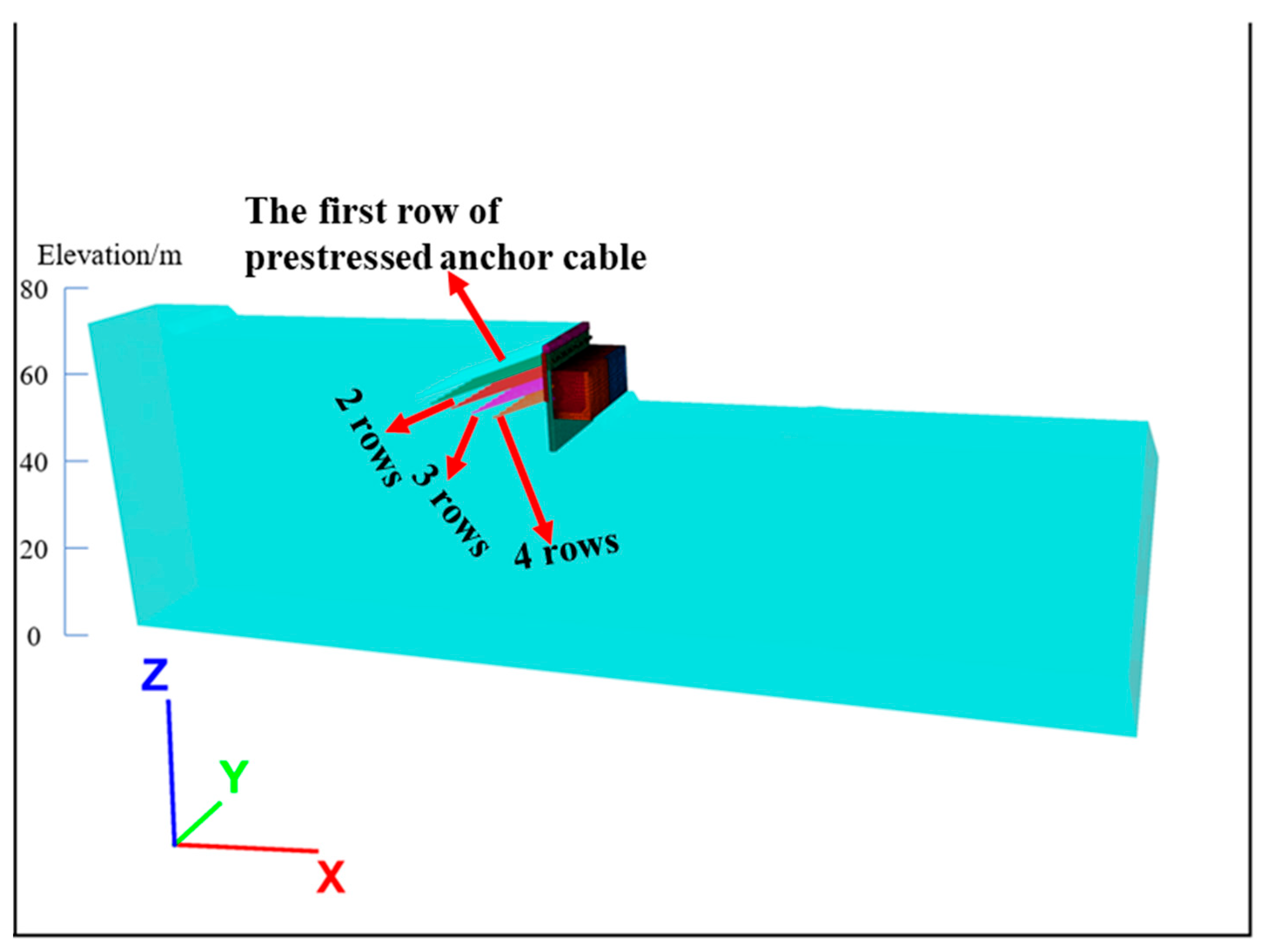

4. Prestressed Anchor Cable Optimization

4.1. Optimization Procedure

4.2. Results Comparative Analysis

4.3. Sensitivity Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, S.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Q.; Fan, W.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, X. Analysis of Influence Factors of Anti-Slide Pile with Prestressed Anchor Cable Based on Bearing and Deformation Characteristics of Pile Body. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, L.; Ma, Y.; Cheng, L.; Yan, R. Research on Failure Treatment of Anchor Cable Anti Slide Pile Based on 3D Modeling and Artificial Intelligence Reduction Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Applied Physics and Computing (ICAPC), Ottawa, ON, Canada, 8–10 September 2022; pp. 341–344. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Liao, W.; Li, L.; Hu, S. Improved Calculation Method for the Internal Force of h-Type Prestressed Anchor Cable Antislide Piles. Int. J. Geomech. 2022, 22, 04022187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-H. Rock Slopes in Hydraulic Projects. In Hydraulic Structures; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 813–868. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, D.A. The Design and Performance of Prestressed Rock Anchors with Particular Reference to Load Transfer Mechanisms. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Aberdee, Scotland, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Su, T.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ye, S. Large Scale Model Test Study of Foundation Pit Supported by Pile Anchors. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Que, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, S. Model Experimental Study on Mechanical Characteristics of Prestressed Concrete (Pc) Wall Piles for Waterway Revetment. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 23, e04965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marek, K.; Wieslaw, B.; Anna, S.G.; Zbigniew, W.; Slawomir, G. Experimental Validation of Deflections of Temporary Excavation Support Plates with the Use of 3D Modelling. Materials 2022, 15, 4856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogolik, S.; Kopras, M.; Szymczak-Graczyk, A.; Tschuschke, W. Experimental Evaluation of the Size and Distribution of Lateral Pressure on the Walls of the Excavation Support. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 73, 106831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthakos, P.P. Ground Anchors and Anchored Structures; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Harran, R.; Terzis, D.; Laloui, L. Mechanics, Modeling, and Upscaling of Biocemented Soils: A Review of Breakthroughs and Challenges. Int. J. Geomech. 2023, 23, 03123004. [Google Scholar]

- Bergado, D.T.; Teerawattanasuk, C. 2D and 3D Numerical Simulations of Reinforced Embankments on Soft Ground. Geotext. Geomembr. 2008, 26, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhang, Z.; Abdel-Rahman, K. The Anti Sliding Mechanism of Adjacent Pile-Anchor Structure Considering Traffic Load on Slope Top. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021, 2021, 6615224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, R.K. Risk-Based Asset Management Framework for Water Distribution Systems. PhD Thesis, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, A.-T.; Reiter, S.; Rigo, P. A Review on Simulation-Based Optimization Methods Applied to Building Performance Analysis. Appl. Energy 2014, 113, 1043–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, Z. Analysis of Deep Foundation Pit Pile-Anchor Supporting System Based on FLAC3D 9.0. Geofluids 2022, 2022, 1699292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuguo, F.; Weiming, W.; Junxi, L.I.U. Robust Optimization Design of Anti-Slide Piles with Prestressed Anchor Cables. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2009, 31, 515–520. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, P.; Mehndiratta, S. Exploring the Efficacy of Slope Stabilization Using Piles: A Comprehensive Review. Indian Geotech. J. 2024, 55, 2442–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soori, M. Artificial Intelligent in Optimization of Steel Moment Frame Structures A Review. Int. J. Struct. Constr. Eng. 2024, 18, 141–158. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosn, M.; Dueñas-Osorio, L.; Frangopol, D.; McAllister, T.; Bocchini, P.; Manuel, L.; Ellingwood, B.; Arangio, S.; Bontempi, F.; Shah, M. Performance Indicators for Structural Systems and Infrastructure Networks. J. Struct. Eng. 2016, 142, F4016003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Xue, J.; Wang, Y.; Yang, M.; Guo, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y. The Use of Machine Learning Models for Predicting Maximum Bridge Pile Lateral Displacements Caused by Excavation of Adjacent Foundation Pit. J. Eng. Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. Advanced Computational Methods and Geomechanics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Casadei, F.; Halleux, J.P. Binary Spatial Partitioning of the Central-Difference Time Integration Scheme for Explicit Fast Transient Dynamics. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 2009, 78, 1436–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SL 677-2014; Specifications for Hydraulic Concrete Construction. China Water Power Press: Beijing, China, 2014.

- Gao, K.; Cheng, Z.; Song, Y.; Yin, S.; Chen, Y. Machine Learning–Driven Surrogate Model Development for Geotechnical Numerical Simulation. Geotech. Res. 2025, 12, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashani, A.R.; Gandomi, A.H.; Azizi, K.; Camp, C. Multi-Objective Optimization of Reinforced Concrete Cantilever Retaining Wall: A Comparative Study. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2022, 65, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandomi, A.H.; Kashani, A.R.; Roke, D.A.; Mousavi, M. Optimization of Retaining Wall Design Using Recent Swarm Intelligence Techniques. Eng. Struct. 2015, 103, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.Z.; Xu, H.D.; Sheng, D.C. Ready-to-Use Deep-Learning Surrogate Models for Problems with Spatially Variable Inputs and Outputs. Acta Geotech. 2023, 18, 1681–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefaniak, K.; Wierzbicki, J.; Ksit, B.; Szymczak-Graczyk, A. Biocementation as a Pro-Ecological Method of Stabilizing Construction Subsoil. Energies 2023, 16, 2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stratum | Elastic (MPa) | Poisson’s Ratio | Strength Parameters | Unit Weight (kN/m3) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| φ′(°) | c′/kP | Natural | Saturated | Dry | |||

| Fill | 7 | 0.35 | 22 | 0 | 19 | 20.0 | 15.8 |

| Sandy Gravel | 15 | 0.275 | 30 | 0 | 21.5 | 21.3 | 17.9 |

| Weakly Weathered Sandstone | 4000 | 0.30 | 37.78 | 575 | 25 | 25.3 | 24.3 |

| Moderately Weathered Sandstone | 6500 | 0.28 | 41.19 | 675 | 25.3 | 25.5 | 24.6 |

| Weakly Weathered Siltstone | 2500 | 0.32 | 32.01 | 425 | 24.2 | 24.8 | 23.5 |

| Moderately Weathered Siltstone | 4000 | 0.30 | 35.94 | 625 | 24.5 | 25.0 | 23.8 |

| Concrete Grade | Density (kg/m3) | Elastic Modulus (GPa) | Poisson’s Ratio | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C30 | 2500 | 30.0 | 0.167 | Buttress retaining walls, Slabs |

| C35 | 2500 | 31.5 | 0.167 | Bored piles, Capping beams, Waling beams |

| Total Length (m) | Design Tensile Force (kN) | Characteristic Tensile Strength (MPa) | Cross-Sectional Area (m2) | Elastic Modulus (kPa) | Free Segment EA (kN) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 1000 | 1860 | 8.60 × 10−4 | 195 × 106 | 167,742 |

| Safety Factor (Pullout) | Characteristic Bond Strength (kPa) | Bond Strength Influence Coefficient | Anchorage Length L (m) | Actual Borehole Diameter (m) | Design Borehole Diameter (m) | Stiffness E (kPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.8 | 125 | 0.7 | 25 | 0.26 | 0.30 | 20 × 106 |

| (kN) | (kN) | (kN) | (kN) | (kN) | ) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optimized prestress values(kN) | 300 | 300 | 500 | 400 | 300 |

| Stage | Moment (kN·m) |

|---|---|

| I | 1125.824 |

| II | 1024.93 |

| III | 798.394 |

| IV | 766.86 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, P.; Jin, H.; Guo, R.; Xu, X.; Li, S.; Meng, Q. Optimization of the Prestress Value for Multi-Row Anchor in Anti-Slide Pile Based on a Staged Orthogonal Design. Designs 2025, 9, 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs9060142

Zhang P, Jin H, Guo R, Xu X, Li S, Meng Q. Optimization of the Prestress Value for Multi-Row Anchor in Anti-Slide Pile Based on a Staged Orthogonal Design. Designs. 2025; 9(6):142. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs9060142

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Peng, Hongjie Jin, Rui Guo, Xiaokun Xu, Shuaikang Li, and Qingxiang Meng. 2025. "Optimization of the Prestress Value for Multi-Row Anchor in Anti-Slide Pile Based on a Staged Orthogonal Design" Designs 9, no. 6: 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs9060142

APA StyleZhang, P., Jin, H., Guo, R., Xu, X., Li, S., & Meng, Q. (2025). Optimization of the Prestress Value for Multi-Row Anchor in Anti-Slide Pile Based on a Staged Orthogonal Design. Designs, 9(6), 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs9060142