Towards Sustainable Construction: Hybrid Prediction Modeling for Compressive Strength of Rice Husk Ash Concrete

Abstract

1. Introduction

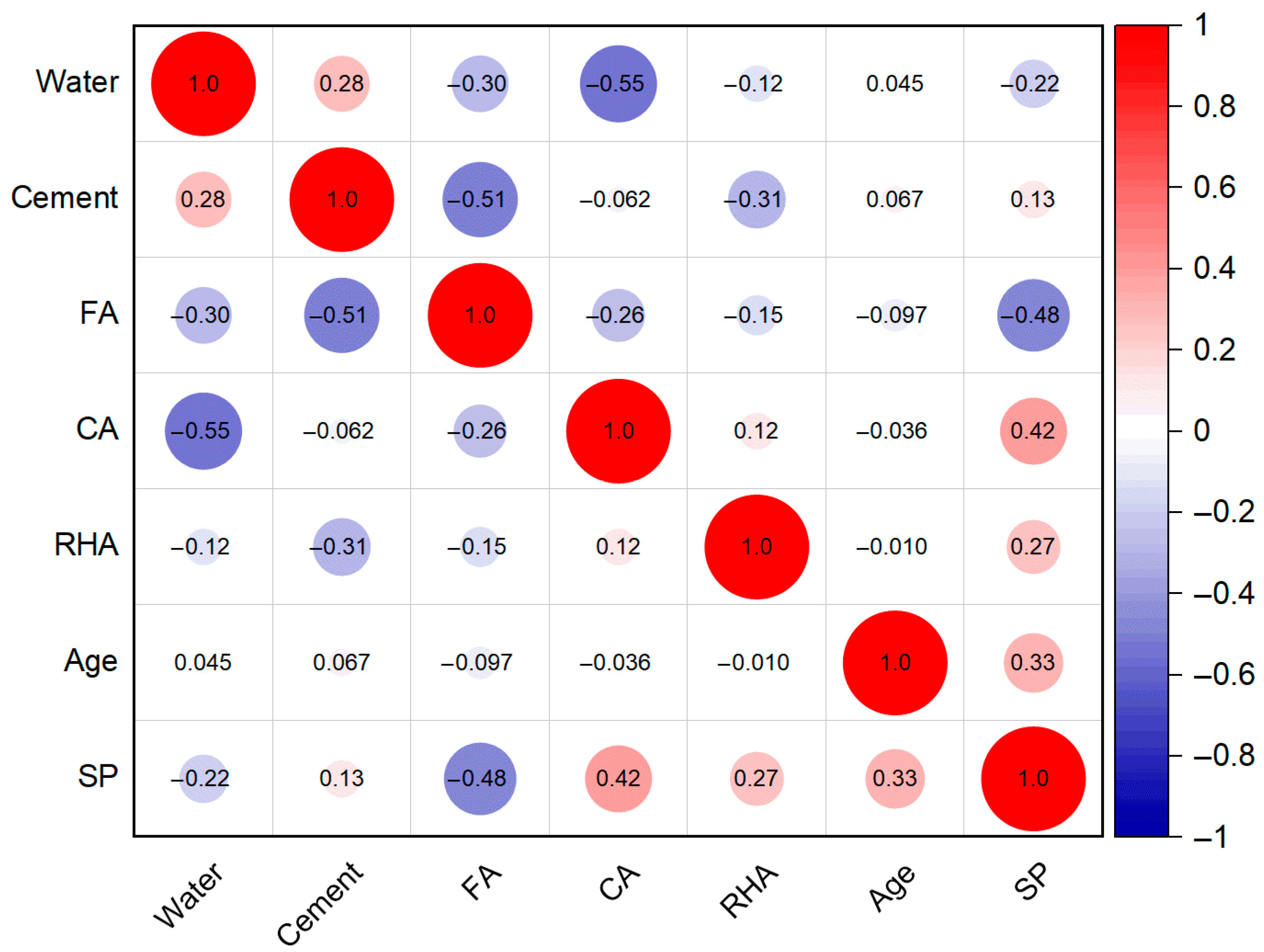

2. Database Description

3. Data-Driven Approaches

3.1. XGBoost

3.2. Northern Goshawk Optimization (NGO)

3.3. Arctic Puffin Optimization (APO)

3.4. Catch Fish Optimization Algorithm (CFOA)

3.5. Cross-Validation

4. Hybrid Model Establishment and Evaluation

- (1)

- Data Splitting: The dataset of 291 samples was initially and randomly split into a training set (80%, 232 samples) and a testing set (20%, 59 samples).

- (2)

- Data Normalization: Z-score normalization was used to carry out the data preprocessing [49]. The mean and standard deviation for each input variable were calculated based on the training set. These derived parameters were then used to normalize both the training and testing sets.

- (3)

- Initial parameter settings: The hyperparameters (subsampling rate, maximum tree depth, learning rate) of the XGBoost models were optimized by NGO, APO, and CFOA. In this study, the subsampling rate is set to [0.5, 1.0]. The search ranges of maximum tree depth and learning rate are [3, 10] and [0.01, 0.3]. Here the maximum tree depth is a discrete variable, while the remaining two parameters are continuous variables. For the XGBoost model of this study, the number of trees, column sampling rate and minimum child weight are 100, 0.8, and 2. L1 and L2 regularization term equal 0 and 1. Moreover, the loss function of XGBoost is the mean squared error.

- (4)

- Cross-Validation: This optimization process was conducted on the training set using five-fold cross-validation. As mentioned above, the training set was partitioned into five folds, and in each iteration, four folds were used for training the model, and the remaining one was chosen for validation. In the process, the fixed random seed was chosen to ensure that all models could be compared under the same data partitioning structure. In addition, early stopping was also applied to prevent overfitting. The coefficient of determination (R2) and root mean square error (RMSE) were used to choose the optimal model. During this process, each model is trained under different population sizes. After performance evaluation is completed, the optimal population size for each model can be determined.

- (5)

- Final Model Training and Evaluation: Once the optimal population size of metaheuristics was identified for a hybrid model, a final model was retrained on the entire training set using this population size. This final model was then evaluated once on the testing set.

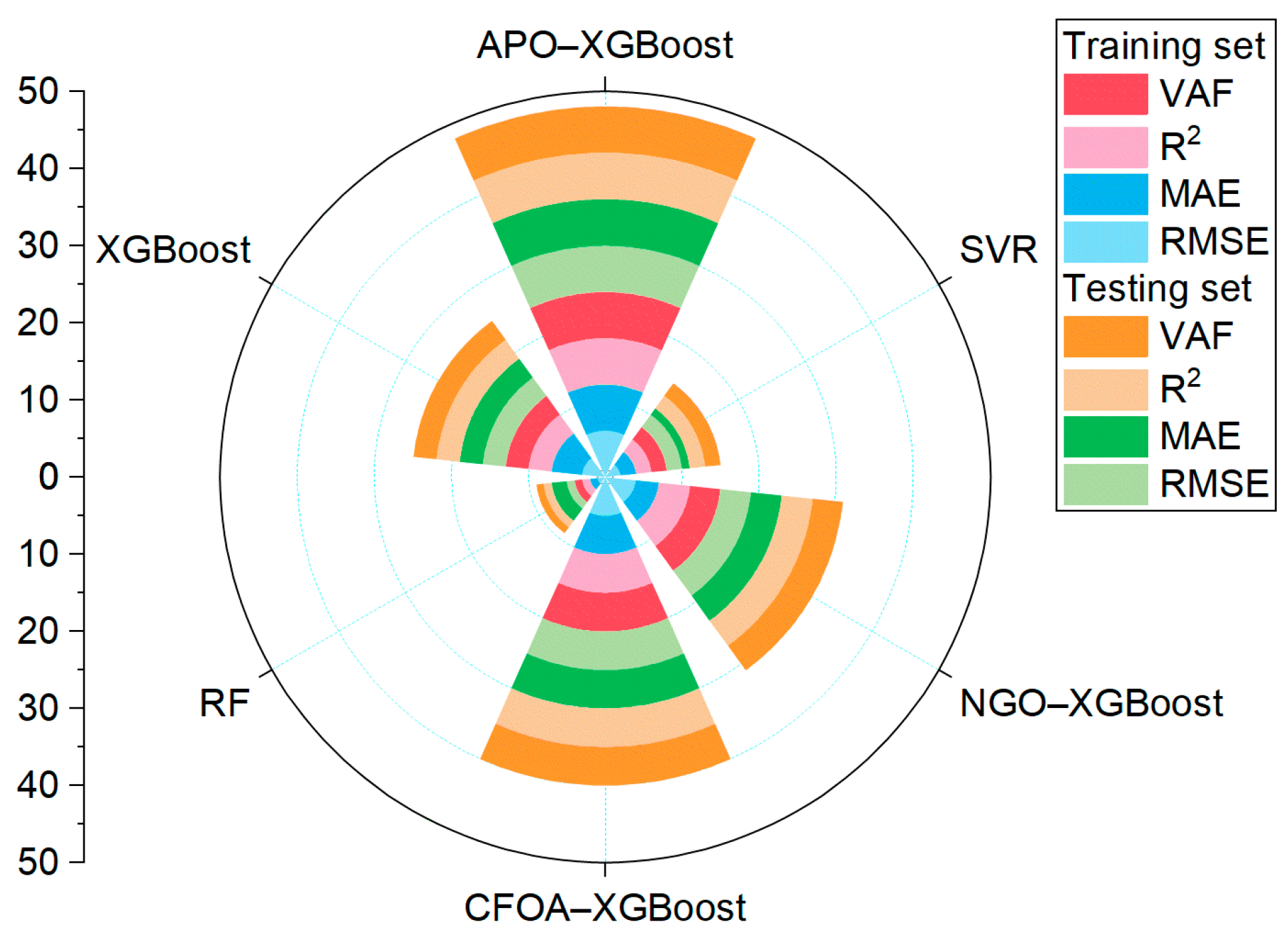

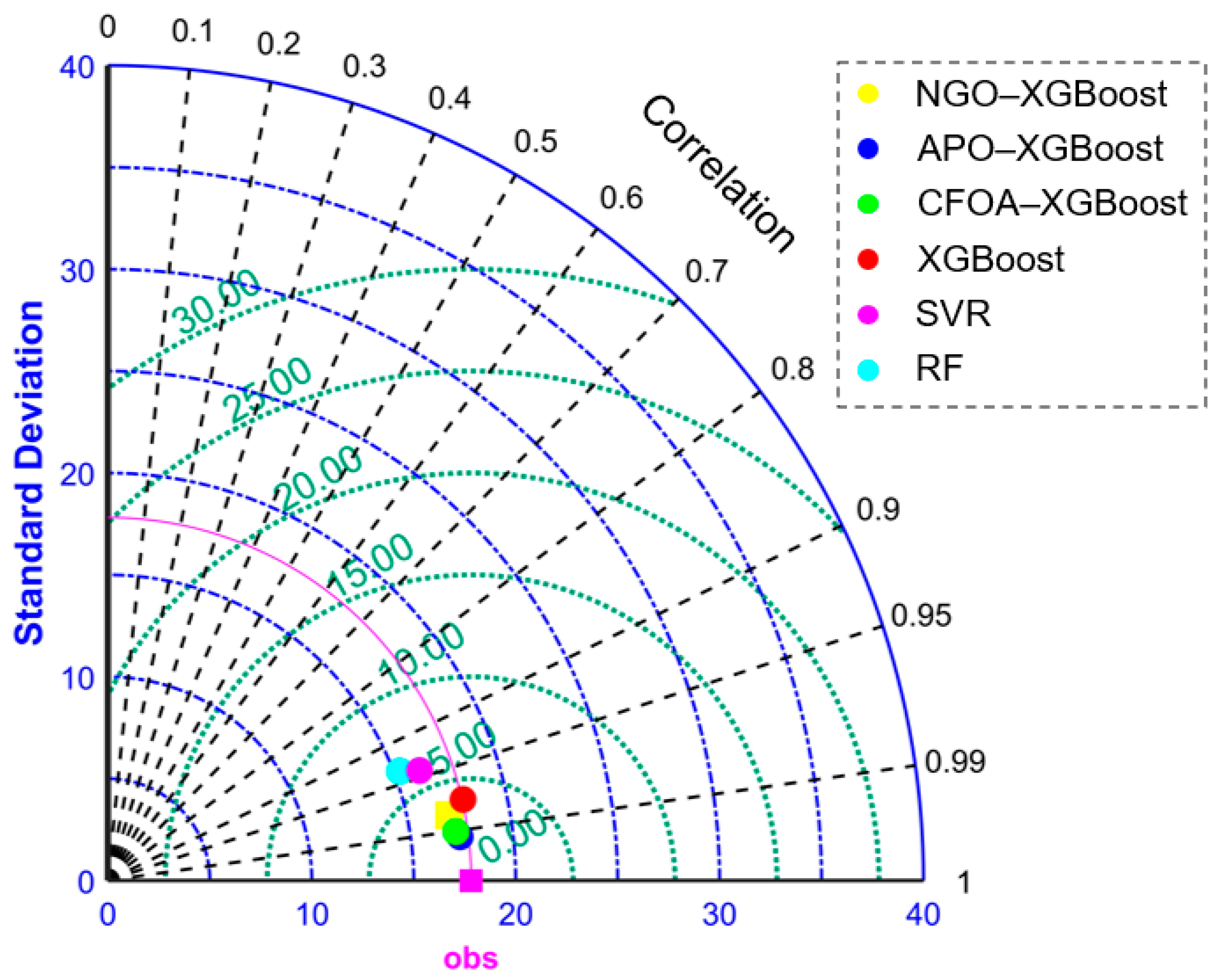

5. Predicted Results of Developed Models

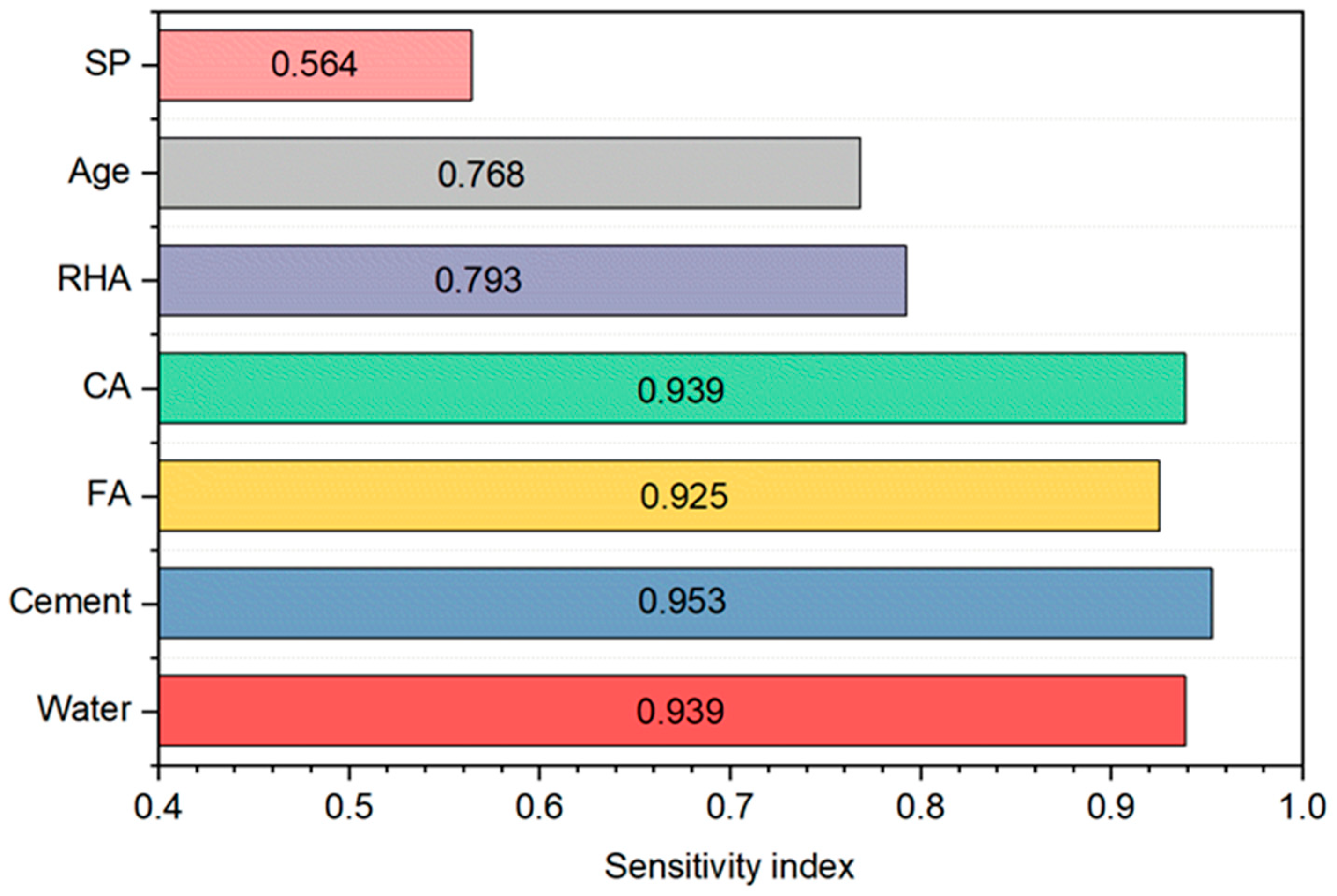

6. Sensitivity Analysis

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

- (1)

- All three hybrid XGBoost models in this study effectively predicted the strength of RHA concrete. The optimization effects of the metaheuristics on XGBoost, in descending order, were: APO, CFOA, NGO. The APO–XGBoost model demonstrated the best prediction performance.

- (2)

- On the training set, the best APO–XGBoost model produced these performance metrics: RMSE = 1.7146, MAE = 1.3350, R2 = 0.9909, and VAF = 99.0873. Meanwhile, the testing set yielded the following results through this optimized model: RMSE = 3.5462, MAE = 2.4494, R2 = 0.9579, VAF = 95.7982. APO–XGBoost model exhibits high prediction accuracy and successfully achieves precise estimation of RHA concrete strength.

- (3)

- Compared to the enhanced XGBoost models, the three baseline models—XGBoost, RF, and SVR—demonstrated reduced prediction accuracy. Advanced hybrid algorithms hold a distinct advantage over classic models in strength estimation of RHA concrete.

- (4)

- The influence of input variables on the RHA concrete strength ranks as follows: Cement > Water = CA > FA > RHA > Age > SP. Cement exhibited a significant correlation with the strength, suggesting that its effect should be prioritized in the mix design of RHA concrete.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adesina, A. Recent Advances in the Concrete Industry to Reduce Its Carbon Dioxide Emissions. Environ. Chall. 2020, 1, 100004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzuki, P.F.; Abduh, M.; Driejana, R. Identification of Source Factors of Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Emissions in Concreting of Reinforced Concrete. Procedia Eng. 2015, 125, 692–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, S.; Liu, H.; Li, Q.; Quan, H.; Gheibi, M.; Fathollahi-Fard, A.M.; Tian, G. Assessment of the Engineering Properties, Carbon Dioxide Emission and Economic of Biomass Recycled Aggregate Concrete: A Novel Approach for Building Green Concretes. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 365, 132780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.M.; Sadoon, A.; Bassuoni, M.T.; Ghazy, A. Utilizing Agricultural Residues from Hot and Cold Climates as Sustainable SCMs for Low-Carbon Concrete. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amran, M.; Fediuk, R.; Murali, G.; Vatin, N.; Karelina, M.; Ozbakkaloglu, T.; Krishna, R.S.; Sahoo, A.K.; Das, S.K.; Mishra, J. Rice Husk Ash-Based Concrete Composites: A Critical Review of Their Properties and Applications. Crystals 2021, 11, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, B.S. Green Concrete Partially Comprised of Rice Husk Ash as a Supplementary Cementitious Material—A Comprehensive Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 3913–3923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endale, S.A.; Taffese, W.Z.; Vo, D.H.; Yehualaw, M.D. Rice husk ash in concrete. Sustainability 2022, 15, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, J.; Si, W.; Khan, M.; McNally, C. Emerging Insights into the Durability of 3D-Printed Concrete: Recent Advances in Mix Design Parameters and Testing. Designs 2025, 9, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Bustamante, O.; Camargo, R.; Duque, J.; Martinez-Arguelles, G.; Polo-Mendoza, R.; Acosta, C.; Murillo, M. Designing Sustainable Asphalt Pavement Structures with a Cement-Treated Base (CTB) and Recycled Concrete Aggregate (RCA): A Case Study from a Developing Country. Designs 2025, 9, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, K.; Rajagopal, K.; Thangavel, K. Rice Husk Ash Blended Cement: Assessment of Optimal Level of Replacement for Strength and Permeability Properties of Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2008, 22, 1675–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, D.; Siddique, R. Strength, Permeability and Microstructure of Self-Compacting Concrete Containing Rice Husk Ash. Biosyst. Eng. 2015, 130, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, R.M.; Nanni, A. Effect of Off-White Rice Husk Ash on Strength, Porosity, Conductivity and Corrosion Resistance of White Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 31, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez de Sensale, G. Strength Development of Concrete with Rice-Husk Ash. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2006, 28, 158–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joel, S. Compressive Strength of Concrete Using Fly Ash and Rice Husk Ash: A Review. Civ. Eng. J. 2020, 6, 1400–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavana Amlashi, A.; Mohammadi Golafshani, E.; Ebrahimi, S.A.; Behnood, A. Estimation of the Compressive Strength of Green Concretes Containing Rice Husk Ash: A Comparison of Different Machine Learning Approaches. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2023, 27, 961–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Zhang, Z.X.; Luo, X.; Huang, Y.; Yu, Z.; Yang, X. Predicting Dynamic Compressive Strength of Frozen-Thawed Rocks by Characteristic Impedance and Data-Driven Methods. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2024, 16, 2591–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Lei, Y.; Zhang, Z.X.; Luo, X.; Aladejare, A.; Ozoji, T. Estimating Dynamic Compressive Strength of Rock Subjected to Freeze-Thaw Weathering by Data-Driven Models and Non-Destructive Rock Properties. Nondestruct. Test. Eval. 2025, 40, 116–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Zhou, S.; Niu, S.; Yu, B.; Wang, Z.; Dai, Z.; Luo, X. Rock Blasting Crack Network Recognition Based on Faster RCNN-ZOA-DELM Model. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2025, 84, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Li, J.; He, B.; Armaghani, D.J.; Huang, S. Advancing Overbreak Prediction in Drilling and Blasting Tunnel Using MVO, SSA and HHO-Based SVM Models with Interpretability Analysis. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resour. 2025, 11, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asteris, P.G.; Armaghani, D.J. An Empirical-Driven Machine Learning (EDML) Approach to Predict PPV Caused by Quarry Blasting. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2025, 84, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armaghani, D.J.; Liu, Z.; Khabbaz, H.; Fattahi, H.; Li, D.; Afrazi, M. Tree-Based Solution Frameworks for Predicting Tunnel Boring Machine Performance Using Rock Mass and Material Properties. CMES-Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2024, 141, 2421–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hashem, M.N.; Amin, M.N.; Raheel, M.; Khan, K.; Alkadhim, H.A.; Imran, M.; Ullah, S.; Iqbal, M. Predicting the Compressive Strength of Concrete Containing Fly Ash and Rice Husk Ash Using ANN and GEP Models. Materials 2022, 15, 7713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.N.; Iftikhar, B.; Khan, K.; Javed, M.F.; AbuArab, A.M.; Rehman, M.F. Prediction Model for Rice Husk Ash Concrete Using AI Approach: Boosting and Bagging Algorithms. Structures 2023, 50, 745–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Das, P.; Kashem, A.; Islam, N. Sustainable of Rice Husk Ash Concrete Compressive Strength Prediction Utilizing Artificial Intelligence Techniques. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 2024, 25, 1349–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovačević, M.; Hadzima-Nyarko, M.; Grubeša, I.N.; Radu, D.; Lozančić, S. Application of artificial intelligence methods for predicting the compressive strength of green concretes with rice husk ash. Mathematics 2023, 12, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Lei, Y.; Luo, X.; Fu, C. Prediction of Compressive Strength of Rice Husk Ash Concrete: A Comparison of Different Metaheuristic Algorithms for Optimizing Support Vector Regression. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 18, e02201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Mei, X.; Dias, D.; Cui, Z.; Zhou, J. Compressive Strength Prediction of Rice Husk Ash Concrete Using a Hybrid Artificial Neural Network Model. Materials 2023, 16, 3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Li, E.; Zhou, J. Predictive Modeling and Interpretation of LC3-ECC Compressive Strength Using XGBoost and Gene Expression Programming. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 49, 113842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Li, E.; Segarra, P.; Xi, B.; Zhou, J. Developing Hybrid XGBoost Model to Predict the Strength of Polypropylene and Straw Fibers Reinforced Cemented Paste Backfill and Interpretability Insights. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2025, 144, 1607–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathiparan, N. Prediction Model for Compressive Strength of Rice Husk Ash Blended Sandcrete Blocks Using a Machine Learning Models. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 2024, 25, 4745–4758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, D.D.; Hu, J.; Stroeven, P. Particle Size Effect on the Strength of Rice Husk Ash Blended Gap-Graded Portland Cement Concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2005, 27, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.N.; Mohd Zain, M.F.; Jamil, M. Prediction of Strength and Slump of Rice Husk Ash Incorporated High-Performance Concrete. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2012, 18, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Yang, L.; Chen, Z.; Yu, Q.J.; Zhao, S.Y.; Shuichi, S. The Strength Property and Pore Distribution of Concrete with Highly Active Rice Husk Ash. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. 2005, 27, 17–20. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Mahmud, H.B.; Malik, M.F.A.; Kahar, R.A.; Zain, M.F.M.; Raman, S.N. Mechanical Properties and Durability of Normal and Water Reduced High Strength Grade 60 Concrete Containing Rice Husk Ash. J. Adv. Concr. Technol. 2009, 7, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao-Lung, H.; Le Anh-Tuan, B.; Chun-Tsun, C. Effect of Rice Husk Ash on the Strength and Durability Characteristics of Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 3768–3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.R.; Singh, D. Effect of Rice Husk Ash on Compressive Strength of Concrete. Int. J. Struct. Civ. Eng. Res. 2019, 8, 223–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, N.; Bhat, J.A. Experimental Investigation of Rice Husk Ash on Compressive Strength, Carbonation and Corrosion Resistance of Reinforced Concrete. Aust. J. Civ. Eng. 2021, 19, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunleye, A.; Wang, Q.G. XGBoost Model for Chronic Kidney Disease Diagnosis. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2019, 17, 2131–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niazkar, M.; Menapace, A.; Brentan, B.; Piraei, R.; Jimenez, D.; Dhawan, P.; Righetti, M. Applications of XGBoost in Water Resources Engineering: A Systematic Literature Review (Dec 2018–May 2023). Environ. Model. Softw. 2024, 174, 105971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, M.; Hubálovský, Š.; Trojovský, P. Northern Goshawk Optimization: A New Swarm-Based Algorithm for Solving Optimization Problems. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 162059–162080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Dabah, M.A.; El-Sehiemy, R.A.; Hasanien, H.M.; Saad, B. Photovoltaic Model Parameters Identification Using Northern Goshawk Optimization Algorithm. Energy 2023, 262, 125522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Jiang, H.; Lyu, L. Multi-Strategy Fusion Improved Northern Goshawk Optimizer Is Used for Engineering Problems and UAV Path Planning. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Tian, W.; Xu, D.; Zang, H. Arctic Puffin Optimization: A Bio-Inspired Metaheuristic Algorithm for Solving Engineering Design Optimization. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2024, 195, 103694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauri, G.; Kashish, M.; Shruti, G.; Iqbal, S.A.; More, J. Load Frequency Control of Multi-Area Power System Using Arctic Puffin Optimization. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 1st International Conference on Smart and Sustainable Developments in Electrical Engineering (SSDEE), Dhanbad, India, 28 February–2 March 2025; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Wen, Q.; Wang, Y.; Mirjalili, S. Catch Fish Optimization Algorithm: A New Human Behavior Algorithm for Solving Clustering Problems. Clust. Comput. 2024, 27, 13295–13332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürses, D.; Mehta, P.; Sait, S.M.; Yıldız, A.R. Battery Box Design of Electric Vehicles Using Artificial Neural Network–Assisted Catch Fish Optimization Algorithm. Mater. Test. 2025, 67, 1463–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Huang, Z.; Huang, H.; Chen, Z.; Li, B. Enhanced Catch Fish Optimization Algorithm: Application in Multi-Threshold Segmentation for Gallbladder Cancer CT Scans. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Image Processing, Multimedia Technology and Machine Learning, Dali, China, 27–29 December 2024; pp. 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappal, S. Data Normalization Using Median Median Absolute Deviation MMAD Based Z-Score for Robust Predictions vs. Min–Max Normalization. Lond. J. Res. Sci. Nat. Form. 2019, 19, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Zorlu, K.; Gokceoglu, C.; Ocakoglu, F.; Nefeslioglu, H.A.; Acikalin, S.J.E.G. Prediction of Uniaxial Compressive Strength of Sandstones Using Petrography-Based Models. Eng. Geol. 2008, 96, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; MacBeth, C. Effects of Learning Parameters on Learning Procedure and Performance of a BPNN. Neural Netw. 1997, 10, 1505–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suthaharan, S. Support Vector Machine. In Machine Learning Models and Algorithms for Big Data Classification: Thinking with Examples for Effective Learning; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 207–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.E. Summarizing Multiple Aspects of Model Performance in a Single Diagram. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2001, 106, 7183–7192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.M.; Park, H.J. A Comparative Study of Fuzzy Based Frequency Ratio and Cosine Amplitude Method for Landslide Susceptibility in Jinbu Area. Econ. Environ. Geol. 2017, 50, 195–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference No. | Dataset Size | Sample Size | Method | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [22] | 310 | cement; fine aggregate; coarse aggregate; water; superplasticizer; fly ash; rice husk ash; age | Gene expression programming, ANN (best model) | R2 = 0.89 (Training); R2 = 0.77 (Testing) |

| [23] | 192 | age, cement, RHA, water, superplasticizer, aggregate | Decision trees, bagging (best model), AdaBoost | R2 = 0.93 (Testing) |

| [24] | 1212 | cement, water, fine aggregate, coarse aggregate, RHA, age, superplasticizer | CatBoost, GBM, CNN, GRU (best model) | R2 = 0.99 (Training); R2 = 0.97 (Testing) |

| [25] | 909 | cement, water, fine aggregate, coarse aggregate, RHA, age, superplasticizer | Multiple linear regression, regression tree, tree bagger, random forest, boosted trees (best model), support vector regression (SVR), neural network, an ensemble of neural networks, Gaussian process regression | R2 = 0.943 (Testing) |

| [26] | 291 | water, fine aggregate, coarse aggregate, cement, RHA, superplasticizer, age | FA–SVR (best model), PSO–SVR, GWO–SVR | R2 = 0.9530 (Training); R2 = 0.9560 (Testing) |

| [27] | 192 | age, cement, RHA, superplasticizer, aggregate, water | CMRSA (circular mapping-reptile search algorithm)–ANN (best model), SOA–SVR, SOA–random forest, ANN, Extreme Learning Machine | R2 = 0.9679 (Training); R2 = 0.9709 (Testing) |

| [30] | 795 | fine aggregate-to-binder ratio, RHA-to-binder ratio, water-to-binder ratio, age | linear regression, ANN, k-nearest neighbors, SVR, eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost, best model) | R2 = 0.94 (Training); R2 = 0.89 (Testing) |

| Variables | Water (kg/m3) | Cement (kg/m3) | FA (kg/m3) | CA (kg/m3) | RHA (kg/m3) | Age (Days) | SP (kg/m3) | CS (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | 165.00 | 450.00 | 633.00 | 1006.70 | 43.60 | 14.00 | 2.60 | 54.62 |

| Maximum | 221.00 | 783.00 | 956.90 | 1324.00 | 153.00 | 91.00 | 72.60 | 92.21 |

| Minimum | 132.40 | 240.00 | 344.00 | 906.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 16.00 |

| Mean | 168.89 | 449.93 | 649.43 | 1061.99 | 44.10 | 21.92 | 6.05 | 53.56 |

| Standard deviation | 24.936 | 90.684 | 111.805 | 141.66 | 34.372 | 24.585 | 9.905 | 17.847 |

| Model | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| XGBoost | n_estimators | 100 |

| max_depth | 8 | |

| colsample_bytree | 0.8 | |

| learning_rate | 0.1 | |

| subsample | 0.6 | |

| min_child_weight | 2 | |

| reg_lambda | 1 | |

| reg_alpha | 0 | |

| RF | max_depth | 18 |

| min_samples_split | 4 | |

| min_samples_leaf | 2 | |

| n_estimators | 250 | |

| SVR | Kernel Type | RBF |

| C | 20 | |

| gamma | 0.05 | |

| epsilon | 0.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, W.; Ji, Y.; Zhou, S.; Ji, L.; Lei, Y.; Wang, M. Towards Sustainable Construction: Hybrid Prediction Modeling for Compressive Strength of Rice Husk Ash Concrete. Designs 2025, 9, 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs9060141

Yang W, Ji Y, Zhou S, Ji L, Lei Y, Wang M. Towards Sustainable Construction: Hybrid Prediction Modeling for Compressive Strength of Rice Husk Ash Concrete. Designs. 2025; 9(6):141. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs9060141

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Wanling, Yasha Ji, Shengtao Zhou, Ling Ji, Yu Lei, and Minhao Wang. 2025. "Towards Sustainable Construction: Hybrid Prediction Modeling for Compressive Strength of Rice Husk Ash Concrete" Designs 9, no. 6: 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs9060141

APA StyleYang, W., Ji, Y., Zhou, S., Ji, L., Lei, Y., & Wang, M. (2025). Towards Sustainable Construction: Hybrid Prediction Modeling for Compressive Strength of Rice Husk Ash Concrete. Designs, 9(6), 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs9060141