Digital Twins in Development of Medical Products—The State of the Art

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ-1:

- What are the main applications of DT-Is in the healthcare industry? Are there successful stories of using DT-Is to develop new medical products other than their applications in remote surgeries, remote diagnoses, personalized medicines, and assistive technologies?

- RQ-2:

- What are the most relevant technologies of DT-Is? Is there any methodological hurdle to creating innovations in sustainable product development?

- RQ-3:

- Is there new technology that can elevate the conventional DT-I concept for sustainable medical product development?

2. Structured Literature Review (SLR)

2.1. Introduction of SLR

2.2. Methods

2.3. Results

- AS-1:

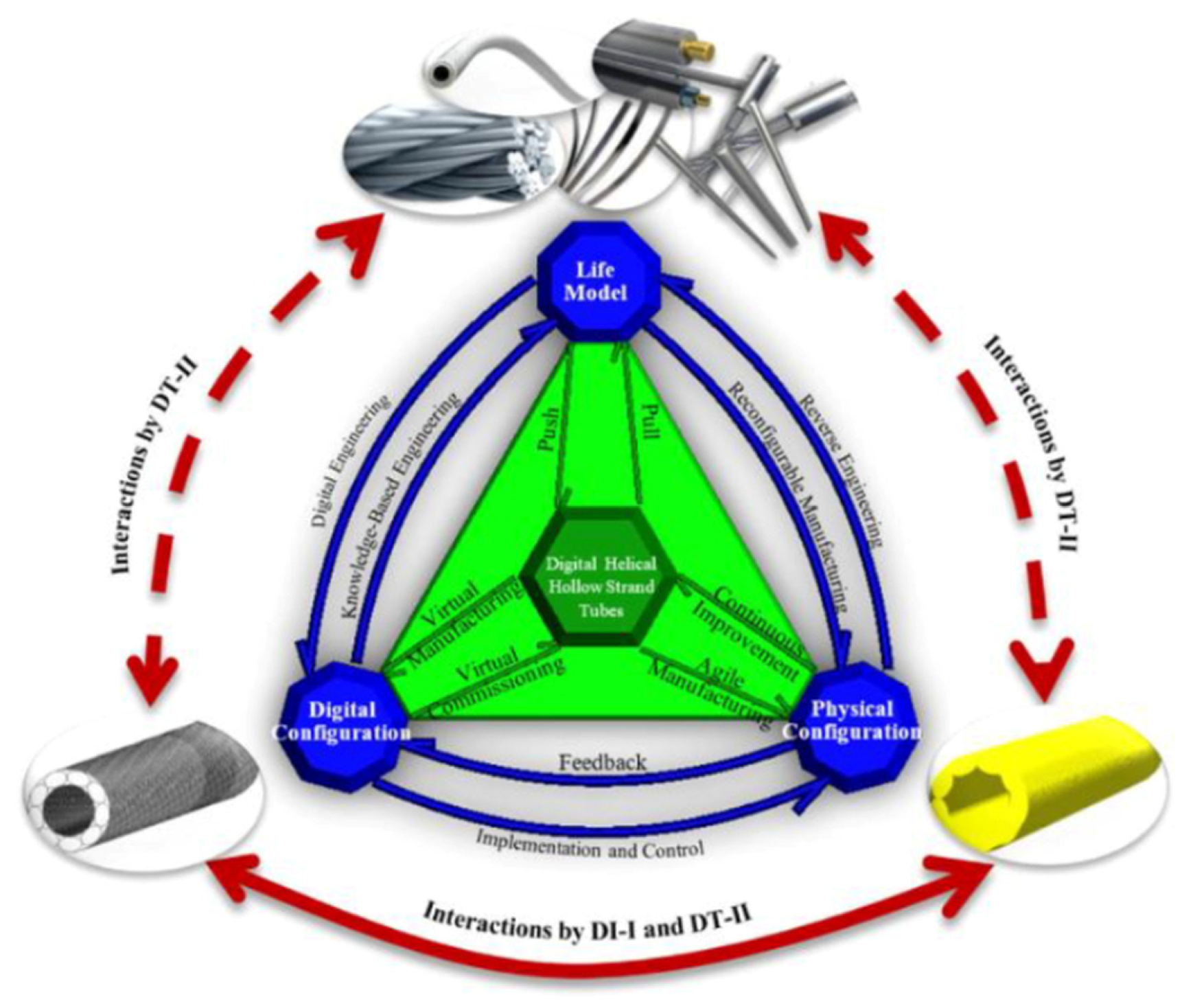

- DT-Is have been widely explored in the healthcare industry for predictive healthcare monitoring and analyses, personalized medical treatments, surgical planning, optimization of caregiving workflows, drug delivery, and drug discovery. However, a very limited number of case studies have been found on using DT-Is to develop new medical products. In particular, only one case study was found to adopt the digital triad (DT-II) to support the sustainable development of medical products. Methodologically, the potential of DT-Is was confined by one-to-one correspondence of digital and physical entities, and the benefits of using DT-Is to maximize knowledge transfer from existing products to new products have yet to be thoroughly explored to accelerate innovation and reduce digital waste.

- AS-2:

- DT-Is are not stand-alone technologies. Most DT-I applications were developed by integrating with numerous newly developed technologies such as AI, IoT, Cyber-Physical Systems (CPSs), Cloud Computing (CC), Edge Computing (EC), Human Robot Interaction (HRI), Blockchain Technologies, Big Data Analytics (BDA), and data-driven techniques for real-time decision-making support.

- AS-3:

- It has been found that DT-II has great potential to elevate existing DT-Is in the sense that a life model is incorporated to maintain all models, methods, and information on legacy products or systems in their evolution, and new products can be conceived, analyzed, prototyped, and virtually verified for personalized medical treatments in the most cost-effective ways.

2.4. Discussion

2.4.1. DT-I Concepts and Variants

2.4.2. Enabling Technologies

2.4.3. Representative Applications

2.5. Conclusion of SLR and Organization of Paper

3. Overview of Bone Fixations

3.1. Principles of Bone Healing and Fixation

3.2. Bone Fixation Techniques

3.3. Applicable Materials

3.4. Limitations of Existing Bone Staples

4. Digital Twins in Biomedical Engineering

4.1. Modeling Bone Healing

4.2. Real-Time Monitoring of Bone Healing

4.3. Predictive Maintenance

5. Simulation of Bone Staples

5.1. Finite Element Analysis (FEA)

5.2. Multi-Scale Modeling

5.3. Verification and Validation

6. Clinical Experiments

6.1. NiTi and Nickel-Free Alloys

6.2. Experiments on Other Materials

6.3. Biodegradable Bone Staples

7. DT-Is in Advancing Bone-Fixing Solutions

7.1. Stress Shielding and Biomechanical Imbalance

7.2. Metal Ion Release and Allergic Reactions

7.3. Complications and Revision Surgeries

7.3.1. Hardware Loosening

7.3.2. Delayed Union and Non-Union

7.3.3. Infections

7.3.4. Adjacent Tissue Damage

7.3.5. Hardware Irritation and Patient Discomfort

7.4. Affordable Patient-Oriented Solutions

7.4.1. Cost of Complications and Revisions

7.4.2. Burden on Patients

7.4.3. Hardware Removals

7.4.4. Resource Allocations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wagg, D.J.; Worden, K.; Barthorpe, R.J.; Gardner, P. Digital twins: State-of-the-art future directions for modelling and simulation in engineering dynamics applications. ASCE—ASME J. Risk Uncertain. Eng. Syst. B Mech. Eng. 2020, 6, 030901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlemann, T.H.-J.; Lehmann, C.; Steinhilper, R. The digital twin: Realizing the cyber-physical production system for industry 4.0. In Proceedings of the 24th CIRP Conference on Life Cycle Engineering, Kamakura, Japan, 8–10 March 2017; Volume 61, pp. 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Z.M. Mechatronics for Complex Products and Systems: Project-Based Design Approaches for Robotics, Cyber-Physical Systems, Digital Twins, and Other Emerging Technology; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2025; ISBN-10: 1394209592, ISBN-13: 978-1394209590. [Google Scholar]

- Classens, K.; Heemels, W.M.; Oomen, T. Digital twins in mechatronics: From model-based control to predictive maintenance. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 1st International Conference on Digital Twins and Parallel Intelligence (DTPI), Beijing, China, 15 July–15 August 2021; Available online: https://www.koenclassens.nl/pdf/ClassensHeeOom2021d.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Bi, Z.; Mikkola, A.; Devpalli, D.; Luo, C. Digital Triads as Next-Generation Mechatronic Systems for Sustainability—A Case Study. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2025, 30, 679–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Z.; Mikkola, A.; Ip, A.W.H.; Yung, K.L.; Luo, C. Virtual verification and validation to enhance sustainability of manufacturing systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 1738–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Fernandez, R.; Godfrey, C.; Holly, C.; Kahlil, H.; Tungpunkom, P. Summarizing systematic re-views: Methodological development, conduct and reporting of an Umbrella review approach. Int. J. Evid. Based Health 2015, 13, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccialli, F.; Amitrano, S.; Cerciello, D.; Borrelli, A.; Prezioso, E.; Canzaniello, M. A digital twin framework for urban parking management and mobility forecasting. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 9400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera-Rivera, A.; Ochoa, W.; Larrinaga, F.; Lasa, G. How-to conduct a systematic literature review: A quick guide for computer science research. MethodsX 2022, 9, 101895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Benedictis, A.; Mazzocca, N.; Somma, A.; Strigaro, C. Digital twins in healthcare: An architectural proposal and its application in a social distancing case study. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2023, 27, 5143–5154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Ahmad, M.; Jeon, G. Integrating digital twins and deep learning for medical image analysis in the era of COVID-19. Virtual Real. Intell. Hardw. 2022, 4, 292–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agouzoul, A.; Tabaa, M.; Chegari, B.; Simeu, E.; Dandache, A.; Alami, K. Towards a digital twin model for building energy management: Case of Morocco. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 184, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhou, H.-Y.; Baptista-Hon, D.T.; Gao, Y.; Liu, X.; Oermann, E.; Xu, S.; Jin, S.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Z.; et al. Concepts and applications of digital twins in healthcare and medicine. Patterns 2024, 5, 101028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diham, D.; Akash, A.I.; Tasneem, Z.; Das, P.; Das, S.K.; Islam, M.R.; Islam, M.M.; Badal, F.R.; Ali, M.F.; Ahamed, M.H.; et al. Digital twin: Data exploration, architecture, implementation and future. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuse, Y.; Murphy, S.N.; Ikari, H.; Takahashi, A.; Fuse, K.; Kawakami, E. Artificial intelligence in clinical data analysis: A review of large language models, foundation models, digital twins, and allergy applications. Allergol. Int. 2025, 74, 499–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowan, N.J. Digital technologies to unlock safe and sustainable opportunities for medical device and healthcare sectors with a focus on the combined use of digital twin and extended reality applications: A review. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 926, 171672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puniya, B.L. Artificial intelligence driven innovations in mechanistic computational modelling and digital twins for biomedical applications. J. Mol. Biol. 2025, 437, 169181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manocha, A.; Afaq, Y.; Bhatia, M. Digital twins assisted blockchain inspired irregular event analysis for eldercare. Knowledge-Based Syst. 2023, 260, 110138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manocha, A.; Sood, S.K.; Bhatia, M. IoT-dew computing inspired real-time monitoring of indoor envi-ronment for irregular health prediction. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 72, 1669–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, S.; Jazdi, N.; Ashtari, B. Intelligent digital twins in health sector: Realization of a software service for requirements and model-based systems engineering. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2022, 55, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashkooli, F.M.; Bhandari, A.; Gu, B.; Kolios, M.C.; Kohandel, M.; Zhan, W. Multiphysics modelling en-hanced by imaging and artificial intelligence for personalized cancer nanomedicine: Foundations for clinical digital twins. J. Control. Release 2025, 386, 114138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, F.P.; Afshari, S.; Ahmed, S.; Albiol, A.; Albiol, F.; Béchet, É.; Bellot, A.C.; Bosse, S.; Burkhard, S.; Chahid, Y.; et al. X-ray simulations with gVXR in education, digital twining, experiment planning, and data analysis. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B 2025, 568, 165804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, S.; Zhao, Z.; Gao, Y.; Liu, D.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.L. Highly sensitive three-dimensional scanning triboelectric sensor for digital twin applications. Nano Energy 2022, 97, 107198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

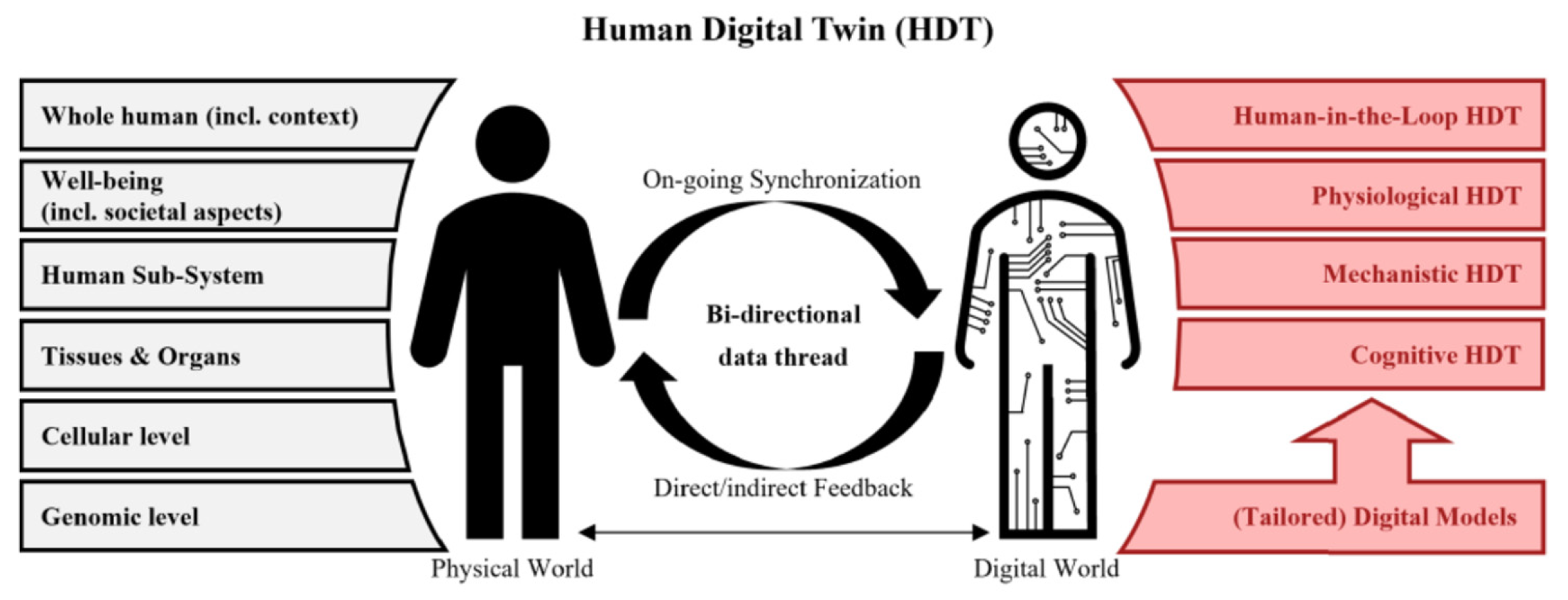

- Sadée, C.; Testa, S.; Barba, T.; Hartmann, K.; Schuessler, M.; Thieme, A.; Church, G.M.; Okoye, I.; Hernandez-Boussard, T.; Hood, L.; et al. Medical digital twins: Enabling precision medicine and medical artificial intelligence. Lancet Digit. Health 2025, 7, 100864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamshiri, S.; Liu, H.; Sohn, I. Adversarial robust image processing in medical digital twin. Inf. Fusion 2025, 115, 102728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Tan, W.; Zhou, L.; Deveci, M.; Ding, W.; Martínez, L.; Pamucar, D. An integrated consensus-oriented decision-making framework for exploring the barriers and applications of medical digital twins. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 284, 127683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, M.M.; Camacho, D.; Park, J.H. Digital Twin and federated learning enabled cyberthreat detection system for IoT networks. Futur. Gener. Comput. Syst. 2024, 161, 701–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshidi, M.; Sargolzaei, S.; Foorginezhad, S.; Moztarzadeh, O. Metaverse and microorganism digital twins: A deep transfer learning approach. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 147, 110798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sai, S.; Prasad, M.; Garg, A.; Chamola, V. Synergizing digital twins and metaverse for consumer heath: A case study approach. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2024, 70, 2137–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islayem, R.; Musamih, A.; Salah, K.; Jayaraman, R.; Yaqoob, I. Enhancing medical digital twins within metaverse using blockchain, NFTs and LLMs. Internet Things 2025, 32, 101648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennigs, C.; Sauer, J.; Bigalke, A.; Hardel, T.; Carbon, N.; Rostalski, P. Towards a digital twin based monitoring tool for ventilated patients. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2024, 58, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M.; Singh, R.P.; Suman, R. Exploring the revolution in healthcare systems through the applications of digital twin technology. Biomed. Technol. 2023, 4, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, A.; Nalepa, J.; Wijata, A.M.; Mahon, J.; Mistry, D.; Knowles, A.T.; Dawson, E.A.; Lip, G.Y.; Olier, I.; Ortega-Martorell, S. Artificial intelligence and digital twins for the personalised prediction of hypertension risk. Comput. Biol. Med. 2025, 196, 110718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alpysbay, N.; Kolesnikova, K.; Chinibayeva, T. Integrating deep learning and reinforcement learning into a digital twin architecture for medical predictions. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 251, 627–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viriyasitavat, W.; Xu, L.; Bi, Z.; Hoonsopon, D. User-oriented selections of validators for trust of internet of things services. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 18, 4859–4867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viriyasitavat, W.; Da Xu, L.; Dhiman, G.; Bi, Z. Blockchain-as-a-service for business process management: Survey and challenges. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2023, 16, 2299–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamakan, S.M.H.; Far, S.B. Distributed and trustworthy digital twin platform based on blockchain and web3 technologies. Cyber Secur. Appl. 2025, 3, 100064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

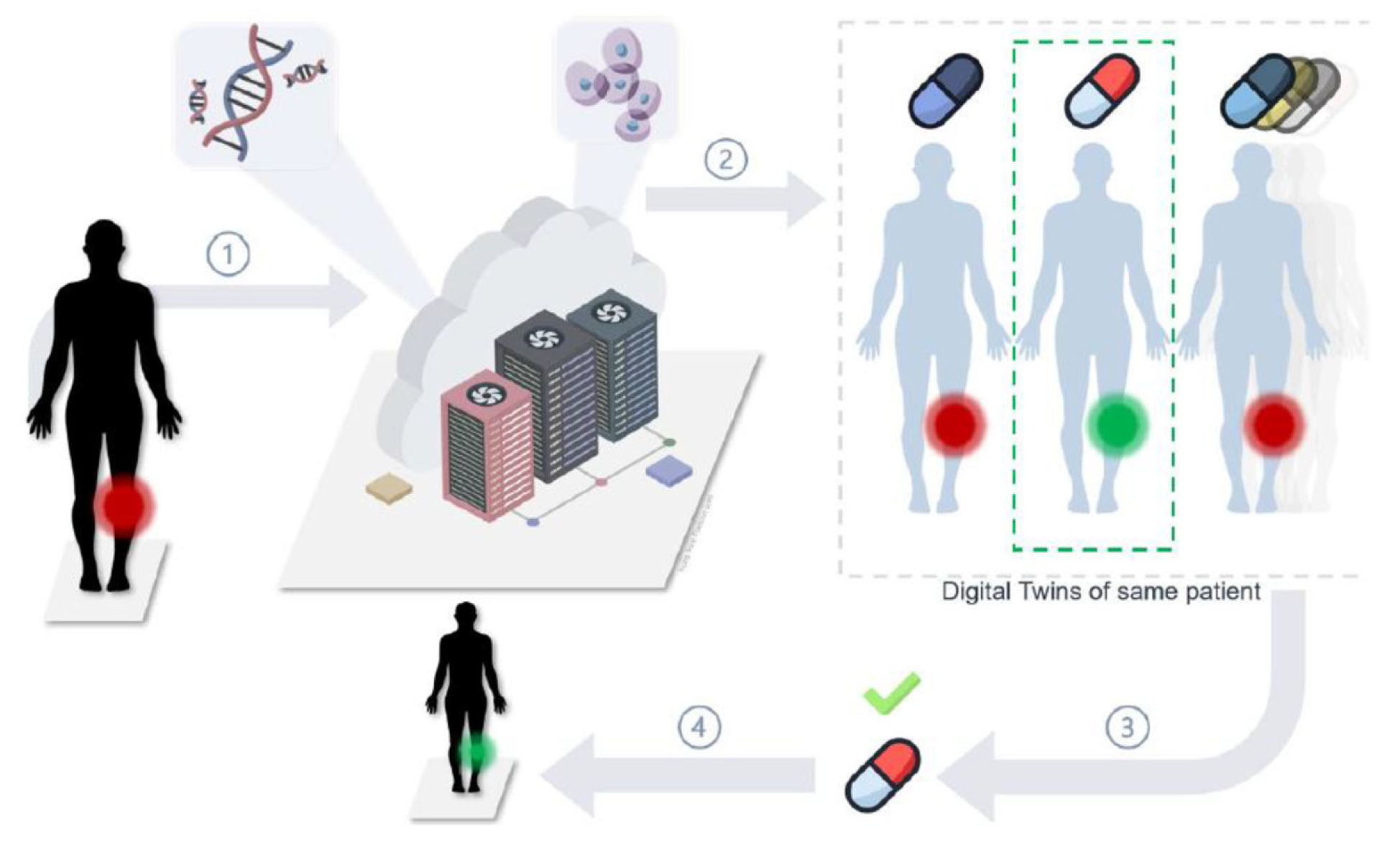

- Ren, Y.; Pieper, A.A.; Cheng, F. Utilization of precision medicine digital twins for drug discovery in Alz-heimer’s diseases. Neurotherapeutics 2025, 22, e00553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piersanti, R.; Bradley, R.; Ali, S.Y.; Quarteroni, A.; Dede’, L.; Trayanova, N.A. Defining myocardial fiber bundle architecture in atrial digital twins. Comput. Biol. Med. 2025, 188, 109774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, M.; Lombardo, G.; Poggi, A. Towards digital twins in healthcare: Optimizing operating room and recovery room dynamics. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 246, 4732–4740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

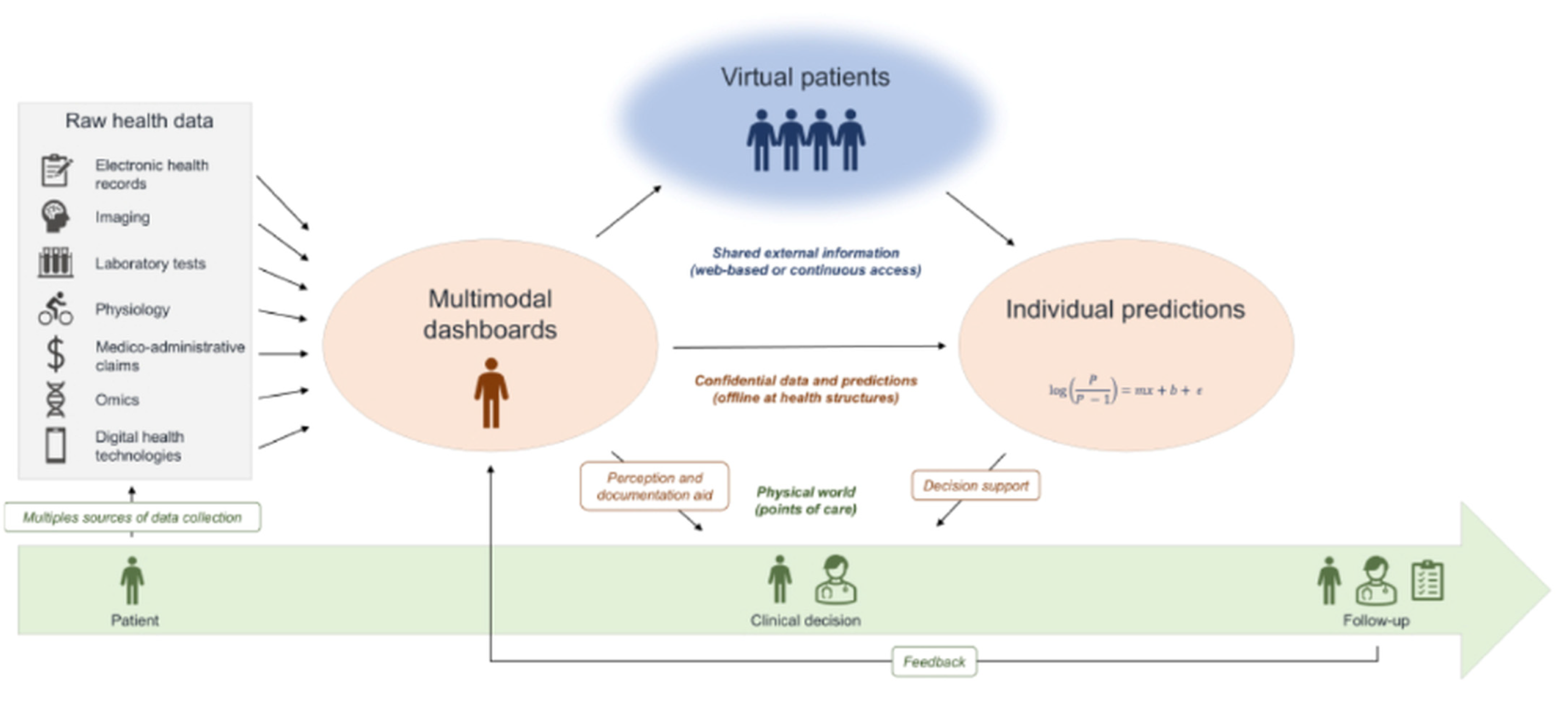

- Moingeon, P.; Chenel, M.; Rousseau, C.; Voisin, E.; Guedj, M. Virtual patients, digital twins and causal disease models: Paving the ground for in silico clinical trials. Drug Discov. Today 2023, 28, 103605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauer-Schmaltz, M.W.; Cash, P.; Hansen, J.P.; Das, N. Human digital twins in rehabilitation: A case study on exoskeleton and serious-game-based stroke rehabilitation using the ETHICA methodology. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 180968–180991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, R.; Shishir, F.S.; Shomaji, S.; Ray, S. Digital twins in healthcare IoT: A systematic review. High-Confidence Comput. 2025, 5, 100340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, A.; Alhajj, R.; Rokne, J. A systematic review of AI as a digital twin for prostate cancer care. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2025, 268, 108804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, T.; Nath, K.; Guravaiah, K. Exploring the adoption and innovation of digital twins in healthcare. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2025, 257, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golse, N.; Joly, F.; Combari, P.; Lewin, M.; Nicolas, Q.; Audebert, C.; Samuel, D.; Allard, M.-A.; Cunha, A.S.; Castaing, D.; et al. Predicting the risk of post-hepatectomy portal hypertension using a digital twin: A clinical proof of concept. J. Hepatol. 2021, 74, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

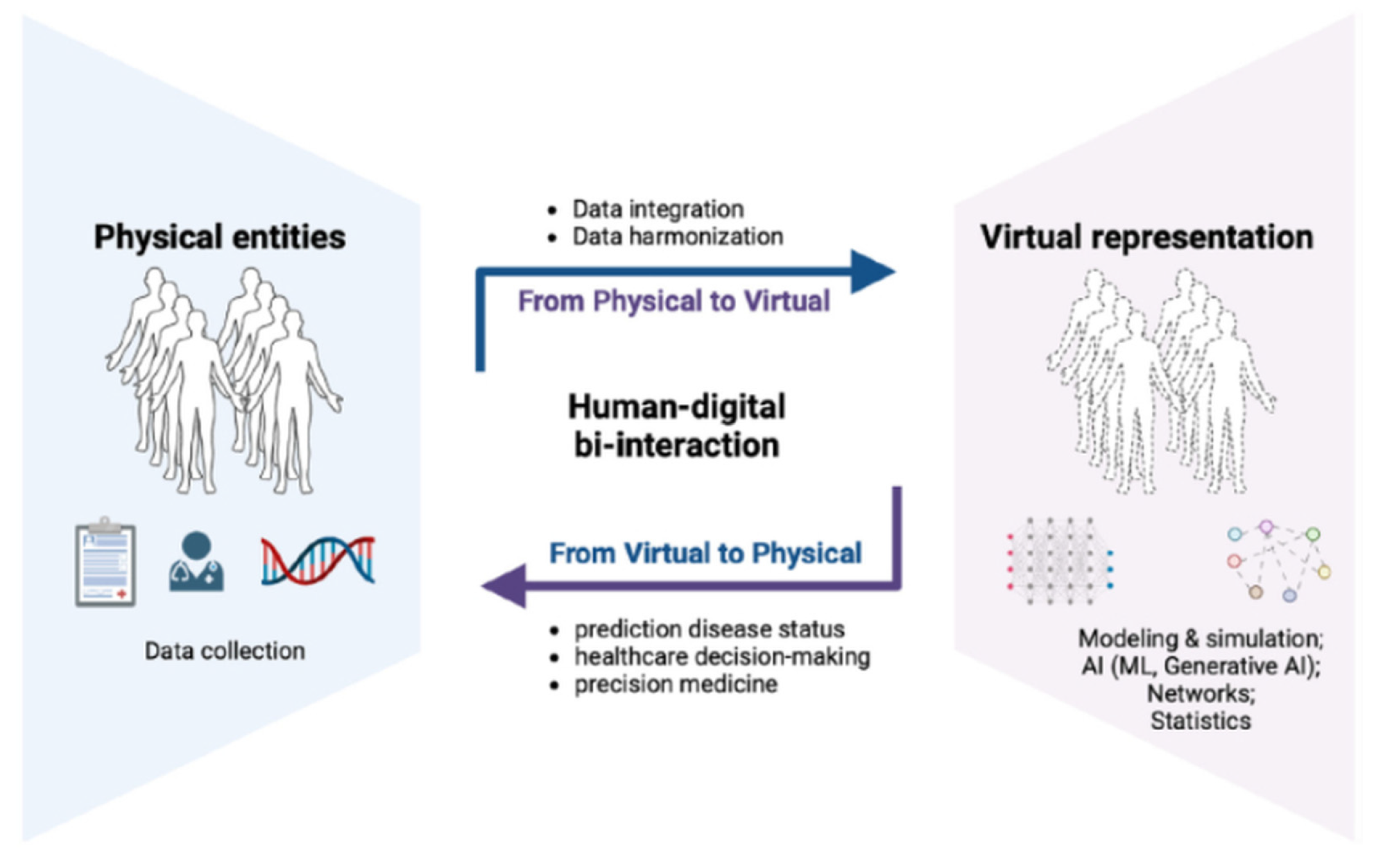

- Demuth, S.; De Sèze, J.; Edan, G.; Ziemssen, T.; Simon, F.; Gourraud, P.-A. Digital representation of patients as medical digital twins: Data-centric viewpoint. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2025, 13, e53542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Fazio, R.; Bartoş, A.; Leonetti, V.; Marrone, S.; Verde, L. Towards hepatic cancer detection with Bayesian networks for patients’ digital twins modelling. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 246, 5104–5113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, M. Digital twin-driven robust bi-level optimisation model for COVID-19 medical waste location-transport under circular economy. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 186, 109107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’AMico, S.; Sauta, E.; Asti, G.; Delleani, M.; Zazzetti, E.; Campagna, A.; Lanino, L.; Maggioni, G.; Ubezio, M.; Todisco, G.; et al. A comprehensive, artificial intelligence, digital twin platform based on multimodal real-world data integration for personalized medicine in hematology. Blood 2024, 144, 2221–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghazali, K.M.; Nima, Z.A.; Hamzah, R.N.; Dhar, M.S.; Anderson, D.E.; Biris, A.S. Bone-tissue engineering: Complex tunable structural and biological responses to injury, drug delivery, and cell-based therapies. Drug Metab. Rev. 2015, 47, 431–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geetha, M.; Singh, A.K.; Asokamani, R.; Gogia, A.K. Ti based biomaterials, the ultimate choice for orthopaedic implants—A review. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2009, 54, 397–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Williams, R.L.; Williams, D.F. The corrosion behavior of Ti–6Al–4V, Ti–6Al–7Nb and Ti–13Nb–13Zr in protein solutions. Biomaterials 1999, 20, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M.; Rack, H.J. Titanium alloys in total joint replacement—A materials science perspective. Biomaterials 1998, 19, 1621–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantovani, D. Shape memory alloys: Properties and biomedical applications. JOM 2000, 52, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyssen, J.P.; Linneberg, A.; Menné, T.; Johansen, J.D. The epidemiology of contact allergy in the general population—Prevalence and main findings. Contact Dermat. 2007, 57, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyssen, J.P.; Menné, T. Nickel allergy in a stratified sample of 3685 adults from the general population: A novel epidemiological approach. Contact Dermat. 2010, 62, 5–10. [Google Scholar]

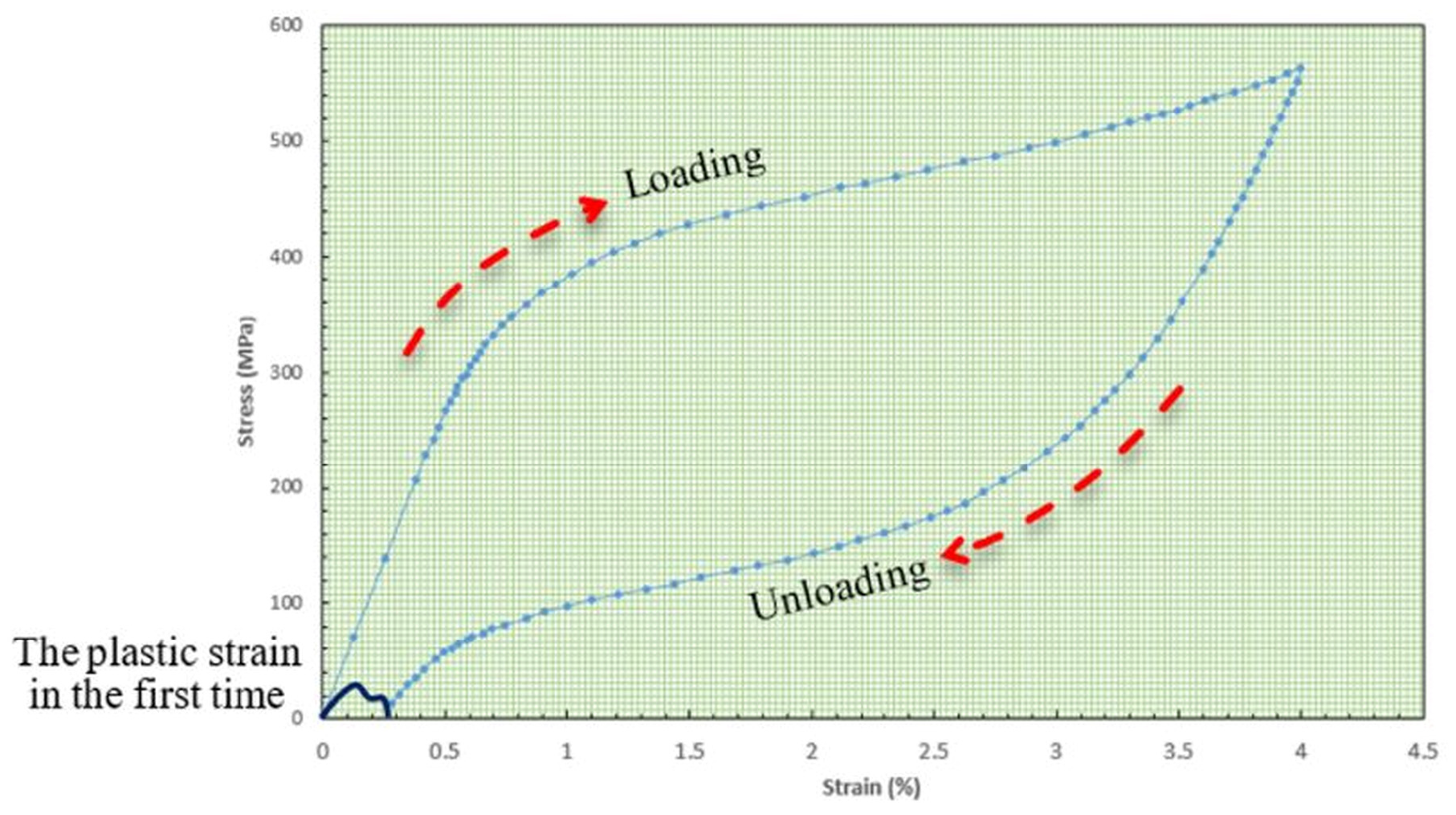

- Cai, S.; Schaffer, J.E.; Ehle, A.L.; Ren, Y. A Ni-free β-Ti alloy with large and stable room temperature su-perelasticity. Mater. Today Commun. 2021, 26, 101838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, T.; Guines, D.; Laillé, D.; Leotoing, L.; Gloriant, T. Finite element analysis of the mechanical performance of self-expanding endovascular stents made with new nickel-free superelastic β-titanium alloys. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2024, 151, 106345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. Use of International Standard ISO 10993-1, “Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices—Part 1: Evalu-Ation and Testing Within a Risk Management Process”. 2025. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/142959/download (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- ASTM F564-24; Standard Specification and Test Methods for Metallic Bone Staples. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2025.

- ISO 13485; Medical Devices—Quality Management Systems—Requirements for Regulatory Purposes. International Organization for Standardization: London, UK, 2016. Available online: https://www.bonnier.net.cn/download/d_20170812100731.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Sun, T.; He, X.; Song, X.; Shu, L.; Li, Z. Digital twins in medicine: Key to the future of healthcare? Front. Med. 2022, 9, 907066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, T.; Wang, J.; Suo, M.; Liu, X.; Huang, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, W.; Li, Z. The digital twin: A potential solution for the personalized diagnosis and treatment of musculoskeletal system diseases. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubert, K.; Germaneau, A.; Rochette, M.; Ye, W.; Severyns, M.; Billot, M.; Rigoard, P.; Vendeuvre, T. Development of digital twins to optimize trauma surgery and postoperative management: A case study focusing on tibial plateau fracture. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 722275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.C.; Hu, D.; Marmor, M.; Herfat, S.T.; Bahney, C.S.; Maharbiz, M.M. Smart bone plates can monitor fracture healing. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barri, K.; Zhang, Q.; Swink, I.; Aucie, Y.; Holmberg, K.; Sauber, R.; Altman, D.T.; Cheng, B.C.; Wang, Z.L.; Alavi, A.H. Patient-specific self-powered metamaterial implants for detecting bone healing progress. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2203533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernigou, P.; Olejnik, R.; Safar, A.; Martinov, S.; Hernigou, J.; Ferre, B. Digital twins, artificial intelligence, and machine learning technology to identify a real personalized motion axis of the tibiotalar joint for robotics in total ankle arthroplasty. Int. Orthop. 2021, 45, 2209–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Y.; Nee, A.Y.C. Digital twin driven prognostics and health management for complex equipment. CIRP Ann. 2018, 67, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Cheng, J.; Qi, Q.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, H.; Sui, F. Digital twin-driven product design, manufacturing and service with big data. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 94, 3563–3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, M.C.; Oeding, J.F.; Diniz, P.; Seil, R.; Samuelsson, K. Leveraging digital twins for improved orthopaedic evaluation and treatment. J. Exp. Orthop. 2024, 11, e70084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonaro, D.; Chiastra, C.; Bologna, F.A.; Audenino, A.L.; Terzini, M. Determining the mechanical properties of super-elastic nitinol bone staples through an integrated experimental and computational calibration approach. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 52, 682–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curenton, T.L.; Davis, B.L.; Darnley, J.E.; Weiner, S.D.; Owusu-Danquah, J.S. Assessing the biomechanical properties of nitinol staples in normal, osteopenic and osteoporotic bone models: A finite element analysis. Injury 2021, 52, 2820–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deichsel, A.; Raschke, M.J.; Herbst, E.; Peez, C.; Oeckenpöhler, S.; Briese, T.; Wermers, J.; Kittl, C.; Glasbrenner, J. The biomechanical stability of bone staples in cortical fixation of tendon grafts for medical collateral ligament reconstruction depends on the implant design. Am. J. Sports Med. 2022, 50, 3827–3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frydrýšek, K.; Čepica, D.; Halo, T.; Skoupý, O.; Pleva, L.; Madeja, R.; Pometlová, J.; Losertová, M.; Koutecký, J.; Michal, P.; et al. Biomechanical analysis of staples for epiphysiodesis. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, L.; Yao, J.; Yamamoto, K.; Sato, T.; Sugita, N. In vivo kinematical validated knee model for preclinical testing of total knee replacement. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 132, 104311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

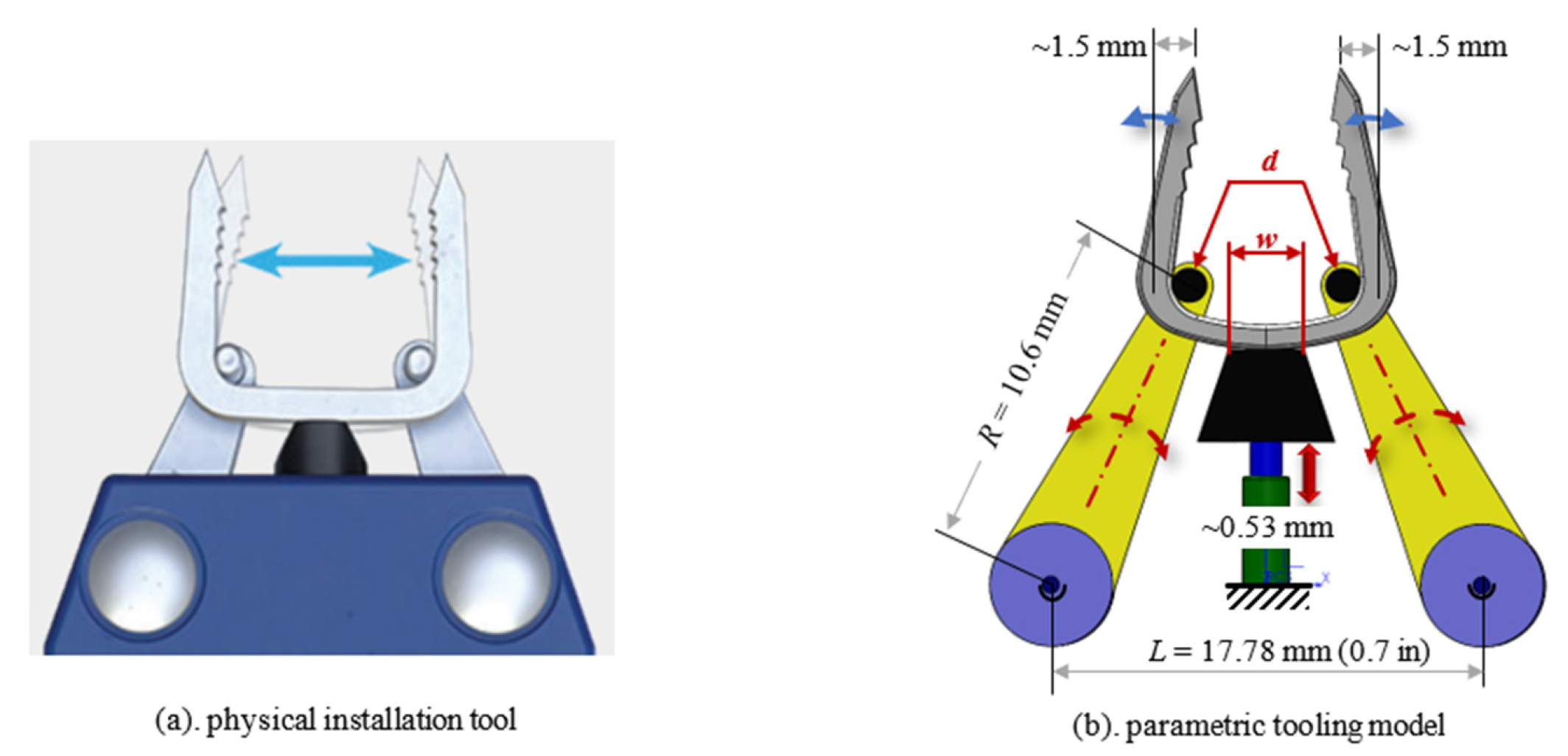

- ORS. Ni-free β-Ti alloy as a potential alternative to Nitinol staples. In Proceedings of the Orthopaedic Research Society Annual Meeting 2025, Phoenix, Arizona, 7–11 February 2025. Annual Meeting Paper No. 572. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, G.S.; Mischler, D.; Wee, H.; Reid, J.S.; Varga, P. Finite Element Analysis of Fracture Fixation. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2021, 19, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, A.R.; Hampton, H.; Dzieza, W.K.; Toussaint, R.J. Nitinol compression staples in foot orthopaedic surgery: A systematic review. Foot Ankle Orthop. 2024, 9, 24730114241300158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravenell, R.A.; Doh, K. Immediate Weightbearing Following First Metatarsal Phalangeal Joint Arthrodesis With 2 Nickel Titanium Alloy Staples. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2024, 63, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dombrowsky, A.R.; Strickland, C.D.; Walsh, D.F.; Hietpas, K.; Conti, M.S.; Irwin, T.A.; Cohen, B.E.; Ellington, J.K.; Jones, C.P.; Shawen, S.B.; et al. Nitinol staple use in primary arthrodesis of Lisfranc fracture-dislocations. Foot Ankle Int. 2024, 45, 690–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.H.N.E.A.; Hanizar, M.A.; Ismail, M.H. Comparative Study on Bending Strength of Metallic Bone Staple. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 7, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deichsel, A.; Glasbrenner, J.; Raschke, M.J.; Klimek, M.; Peez, C.; Briese, T.; Herbst, E.; Kittl, C. Comparison of Time-Zero Primary Stability Between a Biodegradable Magnesium Bone Staple and Metal Bone Staples for Knee Ligament Fixation: A Biomechanical Study in a Porcine Model. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2024, 12, 23259671241236783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amano, H.; Hanada, K.; Hinoki, A.; Tainaka, T.; Shirota, C.; Sumida, W.; Yokota, K.; Murase, N.; Oshima, K.; Chiba, K.; et al. Biodegradable surgical staple composed of magnesium alloy. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, A. Nickel Allergy: Epidemiology, Sources of Exposure, Risk Factors, Clinic and Diagnosis, Prevention and Treatment, Occupational Disease. Int. J. Clin. Stud. Med. Case Rep. 2025, 51, 001275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wawrzynski, J.; Gil, J.A.; Goodman, A.D.; Waryasz, G.R. Hypersensitivity to orthopedic implants: A review of the literature. Rheumatol. Ther. 2017, 4, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinomi, M. Metallic biomaterials. J. Artif. Organs 2008, 11, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M.; Renkawitz, T.; Voellner, F.; Craiovan, B.; Greimel, F.; Worlicek, M.; Grifka, J.; Benditz, A. Revision surgery in total joint replacement is cost-intensive. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 8987104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Materials | Modulus (GPa) | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stainless steel | ~190 | High strength and established uses | High stiffness |

| Ti-6Al-4V | ~110 | Good biocompatibility and corrosion resistance | Al, V toxicity concerns |

| NiTi(Nitinol) | (60, 80) | Shape memory, superelastic, and fatigue-resistant | Ni allergenic |

| Ni-free β-Ti | (55, 85) | No Ni, low modules, and corrosion-resistant | New material and lack of tested data |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bi, Z.; Alfakawi, R.J.R.S.; Abu-Mulaweh, H.; Mueller, D. Digital Twins in Development of Medical Products—The State of the Art. Designs 2025, 9, 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs9060140

Bi Z, Alfakawi RJRS, Abu-Mulaweh H, Mueller D. Digital Twins in Development of Medical Products—The State of the Art. Designs. 2025; 9(6):140. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs9060140

Chicago/Turabian StyleBi, Zhuming, Ruaa Jamal Rabi Salem Alfakawi, Hosni Abu-Mulaweh, and Donald Mueller. 2025. "Digital Twins in Development of Medical Products—The State of the Art" Designs 9, no. 6: 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs9060140

APA StyleBi, Z., Alfakawi, R. J. R. S., Abu-Mulaweh, H., & Mueller, D. (2025). Digital Twins in Development of Medical Products—The State of the Art. Designs, 9(6), 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs9060140