Design and Validation of a CNN-BiLSTM Pulsed Eddy Current Grounding Grid Depth Inversion Method for Engineering Applications Based on Informer Encoder

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. General Context

1.2. Motivation

1.3. Literature Review

1.4. Contribution

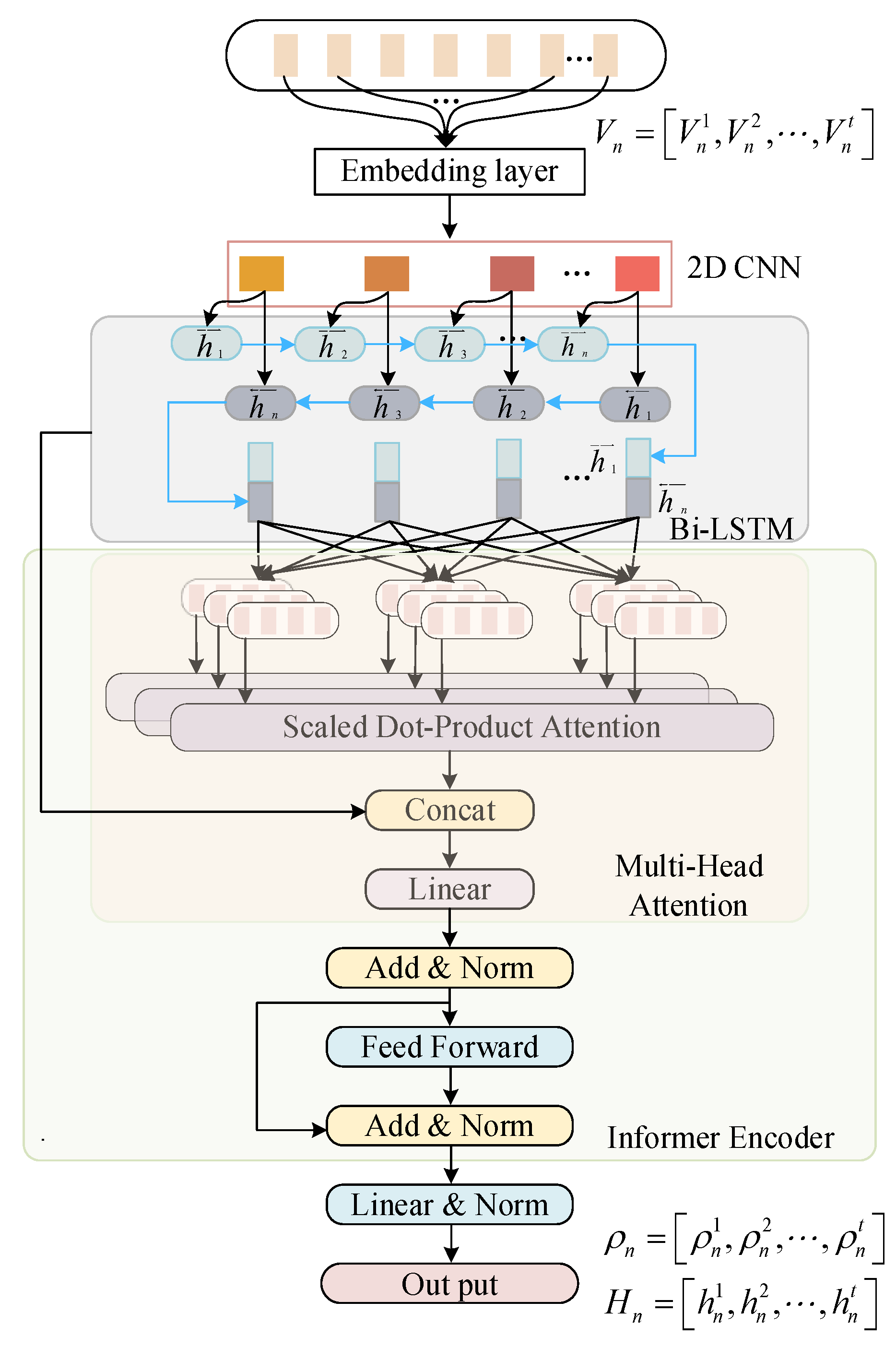

2. Informer Encoder-CNN-BiLSTM Inversion Principle and Method

2.1. Two-Dimensional Spatiotemporal Feature Extraction of Pulsed Eddy Current

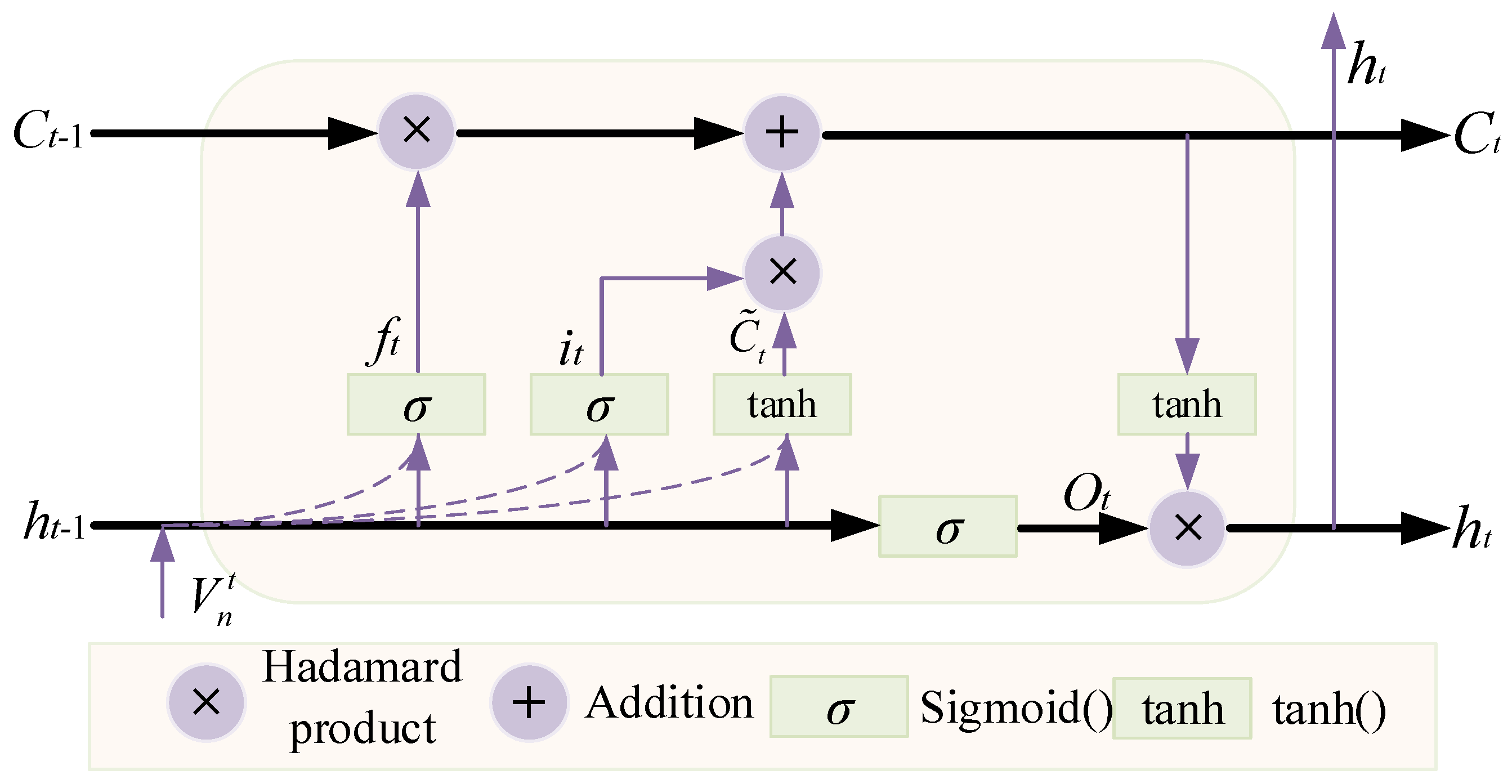

2.2. BiLSTM Deep Inversion Model Construction

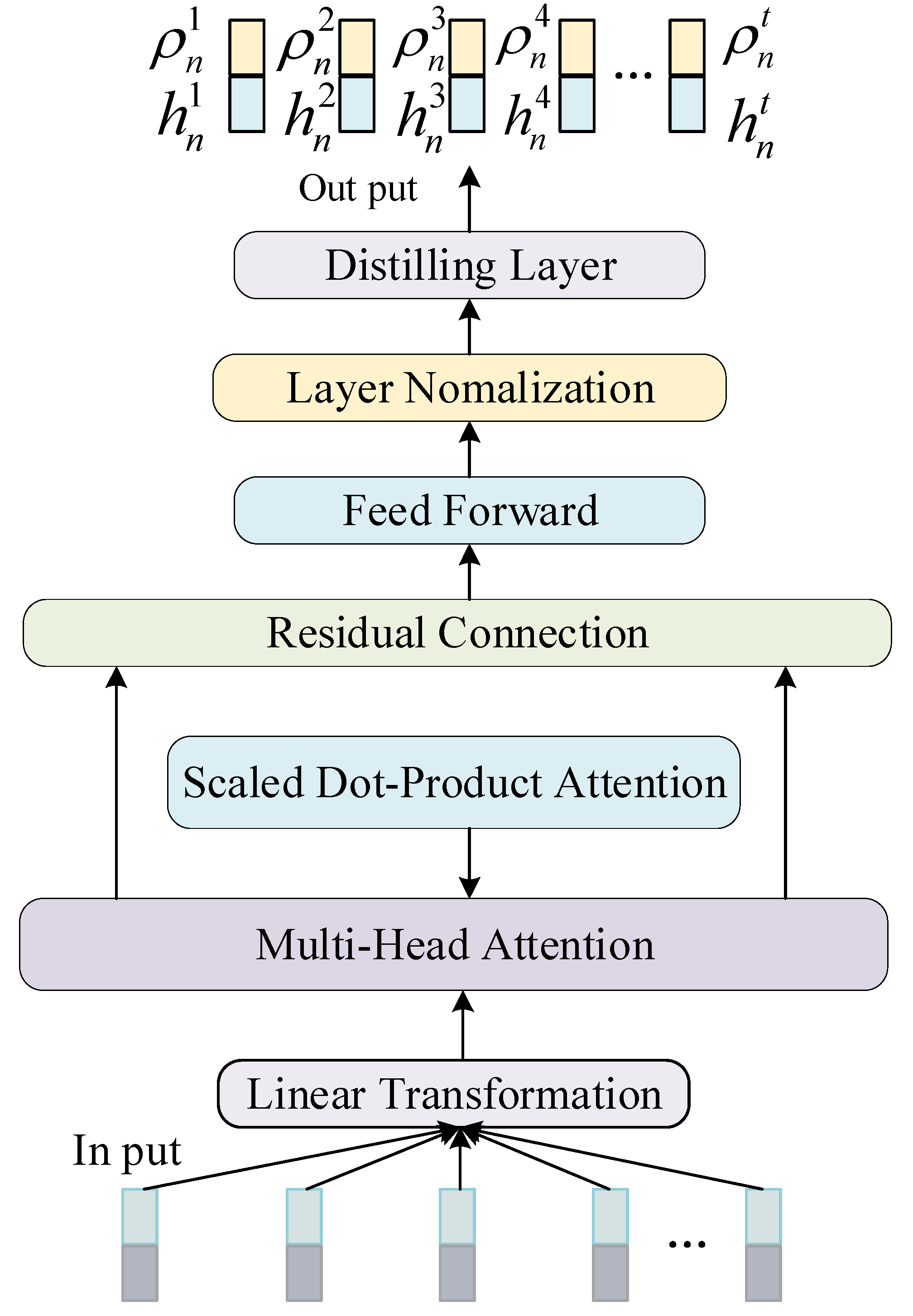

2.3. Informer Encoder Model Construction

3. Informer Encoder-CNN-BiLSTM Inversion Model Construction

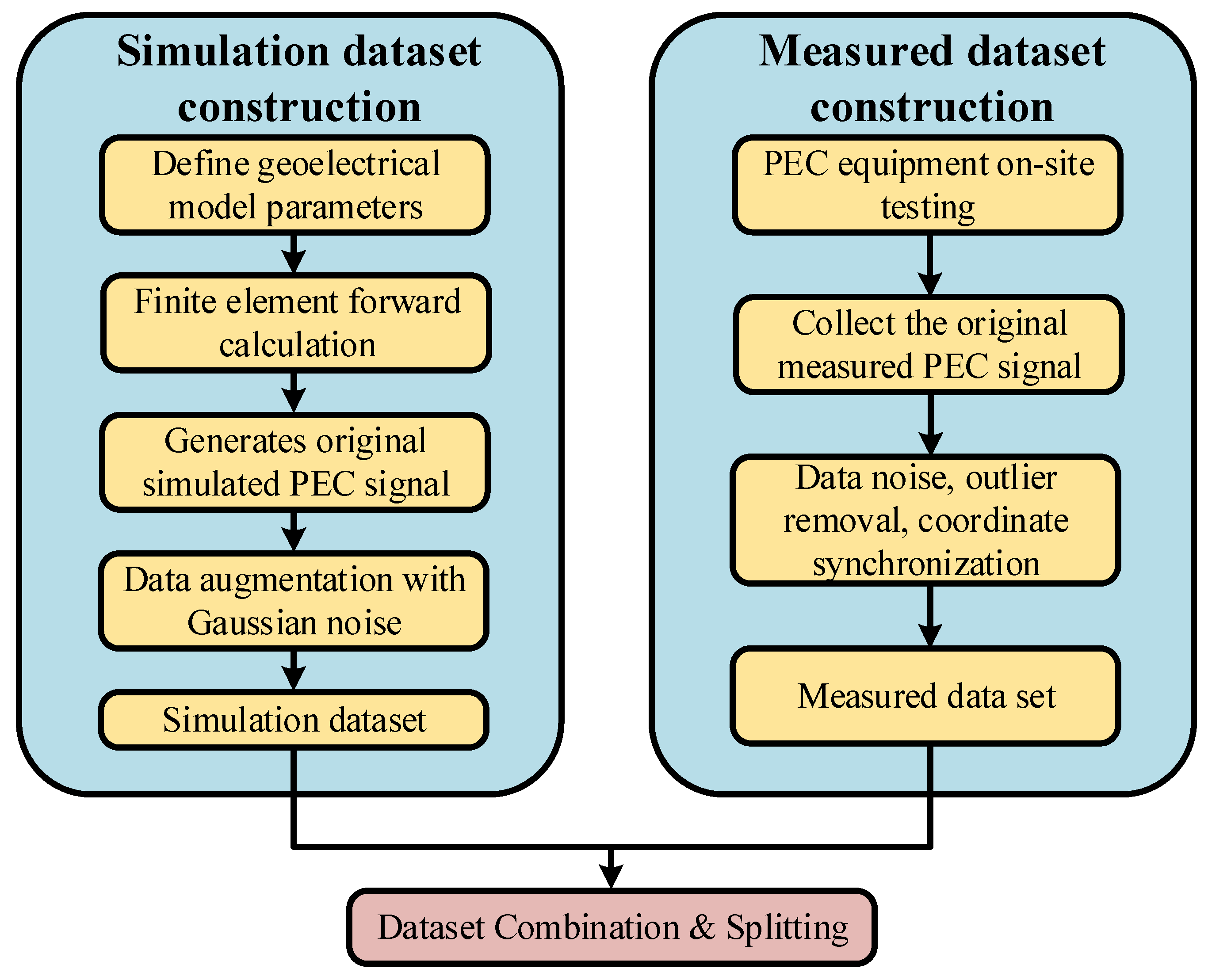

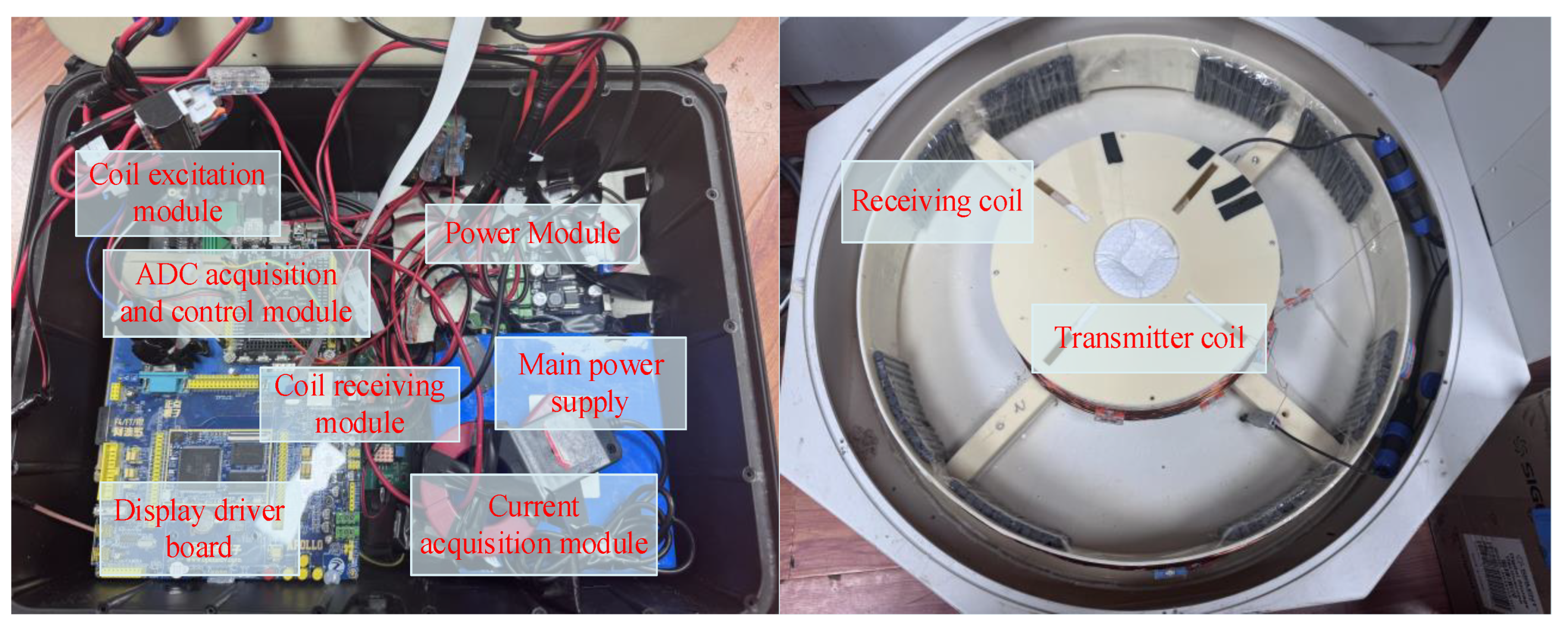

3.1. Pulsed Eddy Current Signal Dataset Construction

3.2. Selection of Inversion Model Evaluation Indicators

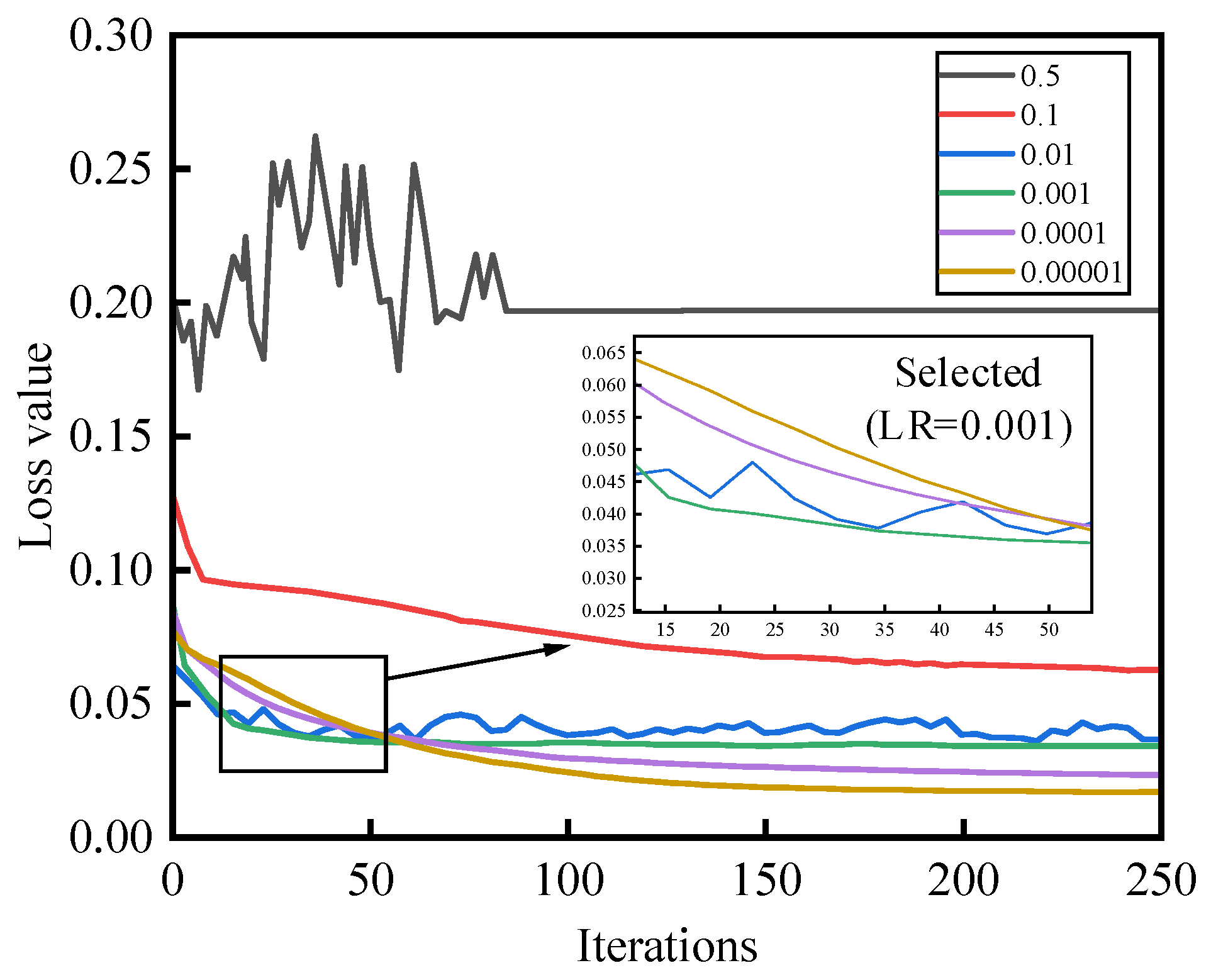

3.3. Inversion Model Learning Rate Selection

3.4. Dropout Value Determination

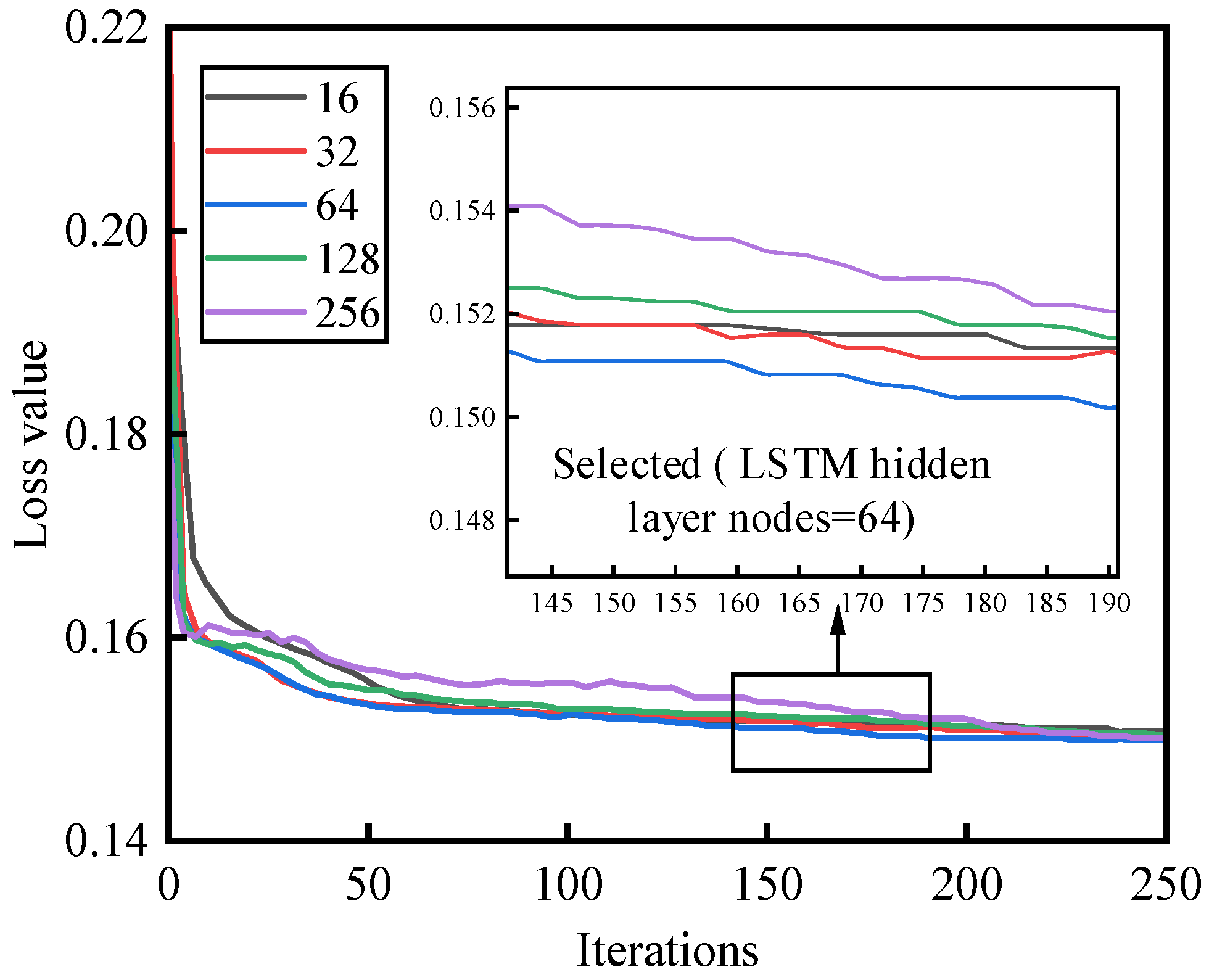

3.5. Setting the Number of Hidden Layer Nodes in the Model

3.6. Ablation Study of Model Structure

4. Practical Application Effect

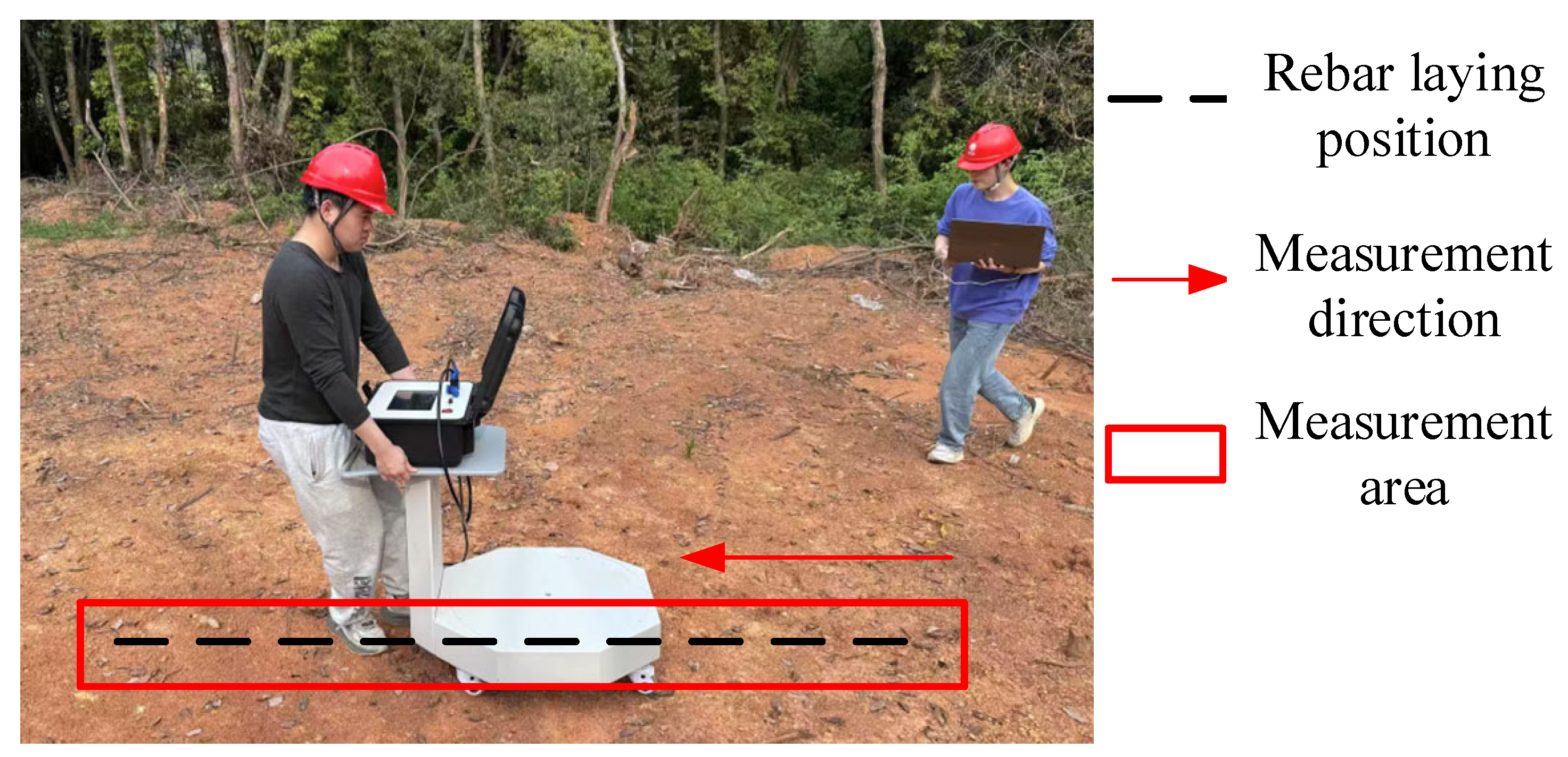

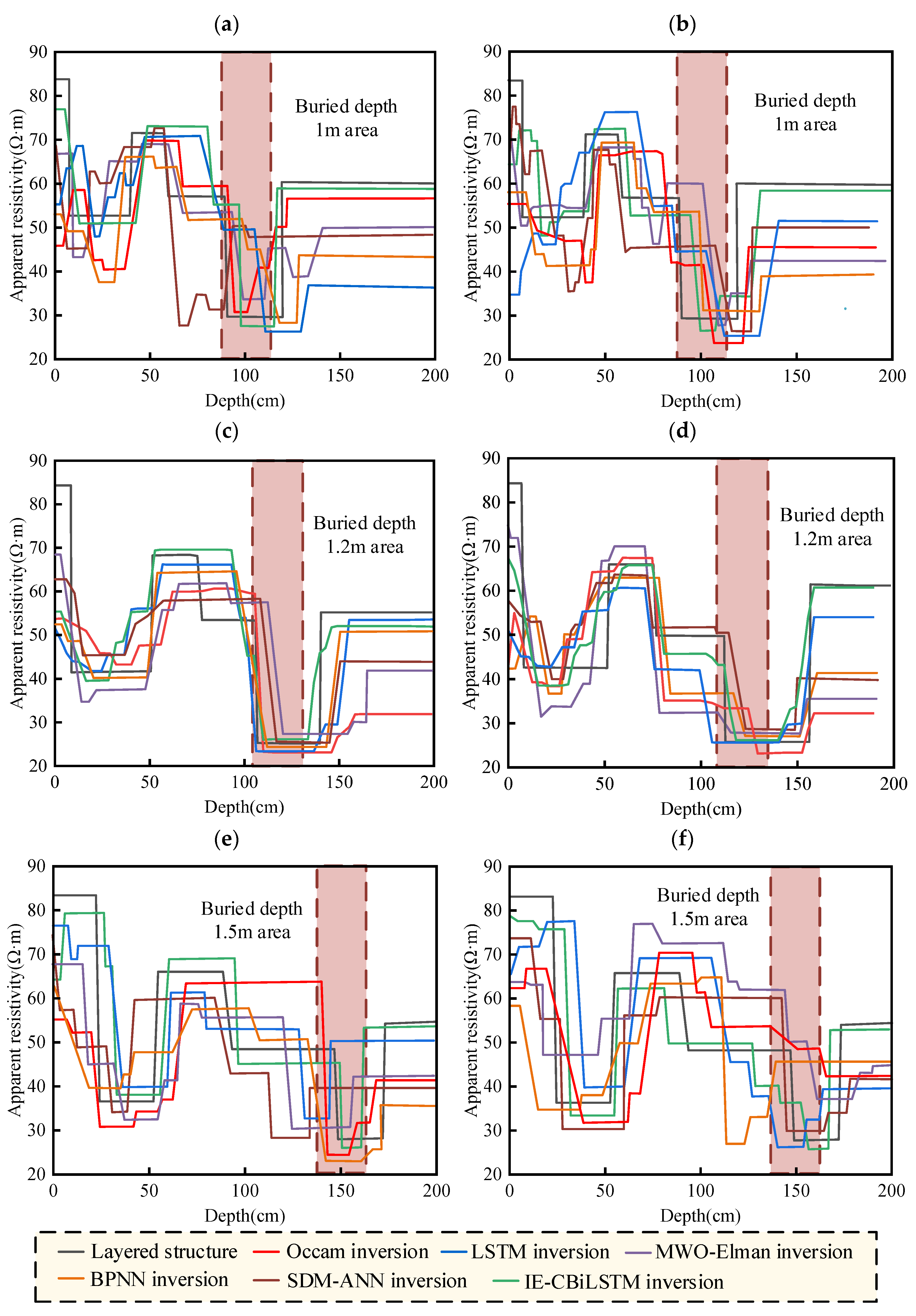

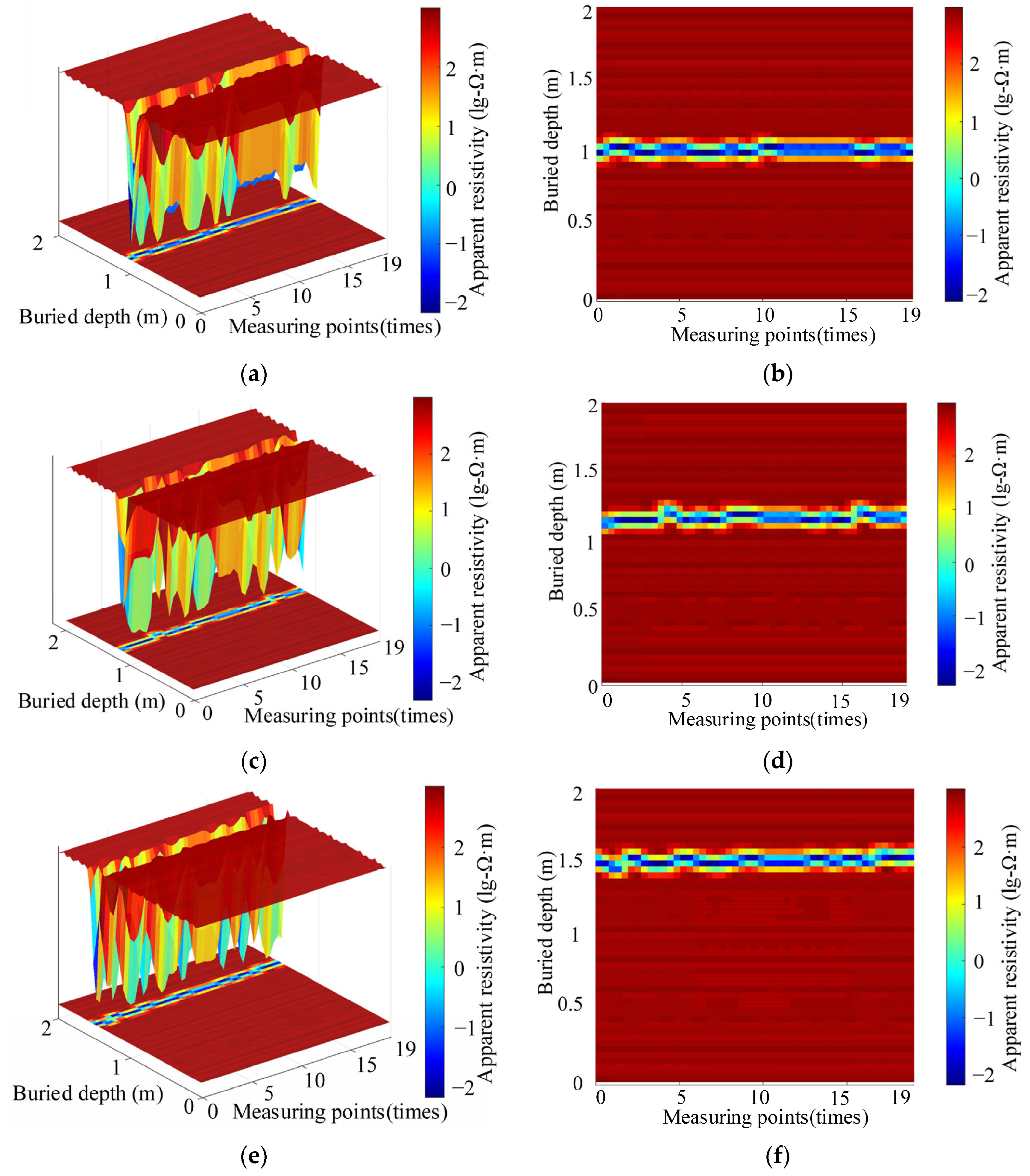

4.1. Self-Burying Test

4.2. On-Site Inversion Test

4.3. Discussion on Advantages and Limitations

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Verification results based on self-burial test measurement data demonstrate that the IE-CBiLSTM method significantly outperforms the MWO-Elman, BPNN, SDM-ANN, Occam, and LSTM methods in inversion accuracy. At three different burial depths (1 m, 1.2 m, and 1.5 m), the inversion results of this method are highly consistent with the actual burial depths. This advantage is further confirmed by evaluation metrics, including an R2 of 0.861, an ERMS of 17.54 Ω·m, and an EMR of 0.061 Ω·m. Furthermore, the three-dimensional and cross-sectional images of the buried depth of the grounded flat steel bars generated using image reconstruction technology accurately reflect the spatial depth of the steel bars and the coordinates of the measurement points, further demonstrating the accuracy and reliability of the IE-CBiLSTM method in simulation scenarios.

- (2)

- In the field inversion test, the inversion results of IE-CBiLSTM were 1.80 m, 1.81 m and 1.80 m, which were highly consistent with the actual burial depth of 1.8 m shown in the engineering drawings. The inversion R2 reached 0.933, and the ERMS and EMR were 11.30 Ω·m and 0.046 Ω·m, respectively, which were better than the comparison model, showing stronger anti-noise ability and generalization performance.

- (3)

- This method fully integrates the spatial and temporal feature extraction mechanisms, effectively enhancing the model’s understanding and expression of complex geoelectric structures while improving the inversion accuracy. Combined with the long sequence modeling advantages of Informer, IE-CBiLSTM has stronger generalization performance and stability. It may offer dependable technological assistance for PEC non-destructive testing and intelligent assessment of grounding grids, and possesses favorable prospects for engineering advancement. In future work, the proposed framework can be further extended by integrating lightweight model compression and edge computing techniques to enable real-time on-site deployment and efficient inversion during field detection.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fan, L.; Li, B.; Zhang, R.; Sun, B.; Dong, L.; Lu, C.; Zhang, D. Simulation analysis of grounding net cathodic protection based on COMSOL. Autom. Instrum. 2021, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Song, H.; Yang, T.; Liu, Y.; Luo, Y. Impulse Characteristics of the Grounding Body for Stereo Pressure Balance Ring of Transmission Lines in Mountain Areas. Insul. Surge Arresters 2023, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, W.; Sun, Y.; Cong, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, S.; Shen, W.; Wang, X. Application of CDEGS in Substation Grounding Grid Design Process. Insul. Surge Arresters 2022, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Lu, C.; Yu, Z.; Ding, S.; Zhang, Z.; Qiu, K. Research on detection method of rebar location and buried depth based on electromagnetic induction. Electron. Meas. Technol. 2021, 44, 119–125. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Hu, S.; Liang, H.; Han, B.; Meng, T. Application of Pulsed Eddy Current Detection Technology in Industry Pipeline Inspection. China Spec. Equip. Saf. 2023, 39 (Suppl. 2), 81–85. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Z.; Yu, C.; Hou, X.; Zhang, H.; Qin, S. Transient Electromagnetic Apparent Resistivity Imaging for Break Point Diagnosis of Grounding Grids. Trans. Chin. Soc. Electrotech. Eng. 2014, 29, 253–259. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, W. On 1D Damped Least Squares Inversion of Large Fixed—Loop Transient Electromagnetic Method. J. Beijing Polytech. Coll. 2025, 24, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Lei, D.; Ren, H.; Yang, L. Smooth quasi-2D inversion of airborne transient electromagnetic data. Prog. Geophys. 2021, 36, 1573–1580. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, L.; Jia, Z.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, G. Sparse Inversion of Gravity and Gravity Gradient Data Using a Greedy Cosine Similarity Search Algorithm. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godio, A.; Santilano, A. On the optimization of electromagnetic geophysical data Application of the PSO algorithm. J. Appl. Geophys. 2018, 148, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, C.; Cheng, B.; Chen, H.; Lv, Y.; Xiong, B.; Zhang, Y.; Hunga, Y. Magnetotelluric Inversion Based on Improved Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2023, 23, 11098–11107. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Q.; Chen, Y.; Sha, F.; Liu, T. Inversion of Rayleigh Wave Dispersion Curve Extracting from Ambient Noise Based on DNN Architecture. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Ou, X.; Tan, J.; Min, X.; Sun, Q. Segmental Regularized Constrained Inversion of Transient Electromagnetism Based on the Improved Sparrow Search Algorithm. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Gong, H.; Sun, G.; Wang, A.; Dai, Y. Research on residual wall thickness inversion of oil and gas pipeline with cladding based on support vector machine. Oil Gas Storage Transp. 2021, 40, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, X.; Wang, M.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Sheng, S.; Lv, J. Discrimination of earthquake and quarry blast based on multi-input convolutional neural network. Chin. J. Geophys. 2022, 65, 1802–1812. [Google Scholar]

- Grochowalski, J.M.; Chady, T. Rapid Identification of Material Defects Based on Pulsed Multifrequency Eddy Current Testing and the k-Nearest Neighbor Method. Materials 2023, 16, 6650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, S.; Huang, W.; Huang, L.; Liu, X. A Hybrid Inversion Method Based on SDM and ANNs Considering Electromagnetic Response Laws. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5923610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Zhao, J.; Dong, Y.; Dong, Q. Quantitative prediction of water abundance in rock mass by transient electro-magnetic method with LBA-BP neural network. J. China Coal Soc. 2020, 45, 330–337. [Google Scholar]

- Han, X.; Deng, C.; Fu, T.; Xia, P.; Liu, X. Transient Electromagnetic Defect Identification of Grounding Grid Based on MWOA-Elman Neural Network. J. Guangxi Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 41, 53–66. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, T.; Xue, G.; Li, P.; Yan, B.; Bao, L.; Song, J.; Ren, X.; Li, Z. TEM real-time inversion based on long-short term memory network. Chin. J. Geophys. 2022, 65, 3650–3663. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, S.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z. An estimation method of sound speed profile based on grouped dilated convolution informer model. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 12, 1484098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Dong, H. Microseismic Event Recognition Method Based on Improved U-Net. J. Jilin Univ. (Earth Sci. Ed.) 2025, 55, 970–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, J.; Cai, H.; Xiong, Y.; He, Z.; Hu, X. Ground-based Towed Transient Electromagnetic Imaging Method Based on Deep earning. Chin. J. Eng. Geophys. 2022, 19, 536–545. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, Y.X.; Wu, J.W.; Chen, Y.D. Seismic-inversion method for nonlinear mapping multilevel well-seismic matching based on bidirectional long short-term memory networks. Appl. Geophys. 2022, 19, 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C. Research on Magnetotelluric Inversion Based on Improved Neural Network. Master’s Thesis, Jilin University, Changchun, China, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Transient electromagnetic numerical simulation based on the transformer neural network. Coal Geol. Explor. 2024, 52, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Yuan, Z.; Guo, Z.; Cheng, Z. A Remote Sensing Retrieval Method For River Water Turbidity Based on a Convolutional Neural Network. J. Geo-Inf. Sci. 2025, 27, 1305–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Bi, W.; Mughees, N. Enhanced Hyperspectral Image Classification Technique Using PCA-2D-CNN Algorithm and Null Spectrum Hyperpixel Features. Sensors 2025, 25, 5790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yang, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, H.; Zhou, W.; Huang, Z.; Lai, F. Log data reconstruction method based on enhanced bidirectional long short-term memory neural network. Prog. Geophys. 2022, 37, 1214–1222. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.-J.; Gao, M.-Y.; Xu, S.-K.; Liu, S.-X.; Yan, H.; Wang, Y. Research on ECT image reconstruction method based on Long Short-Term Memory Network (LSTM). Flow Meas. Instrum. 2024, 95, 102504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, R.K.; Patil, S.N.; Falkowski-Gilski, P.; Łubniewski, Z.; Poongodan, R. Feature Weighted Attention—Bidirectional Long Short Term Memory Model for Change Detection in Remote Sensing Images. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Victoria, J.C.; Netzahuatl-Muñoz, A.R.; Cristiani-Urbina, E. Long Short-Term Memory and Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory Modeling and Prediction of Hexavalent and Total Chromium Removal Capacity Kinetics of Cupressus lusitanica Bark. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, K.; Fraihat, S.; Al-Naymat, G.; Sanjalawe, Y. ECG-CBA: An End-to-End Deep Learning Model for ECG Anomaly Detection Using CNN, Bi-LSTM, and Attention Mechanism. Algorithms 2025, 18, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Fu, H.; Han, Z.; Zhang, X.; Jin, H. Intelligent tool wear prediction based on Informer encoder and stacked bidirectional gated recurrent unit. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. Int. J. Manuf. Prod. Process Dev. 2022, 77, 102368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Wang, J.; Sun, L.; Li, Y.; Xia, H.; He, W. Optimal Electrode Configuration and System Design of Compactly-Assembled Industrial Alkaline Water Electrolyzer. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 299, 117875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Guo, X.-B.; Tian, F.; Shi, Y.; Wang, W.-H.; Sun, H.-R.; Ke, X. Seismic velocity inversion based on CNN-LSTM fusion deep neural network. Appl. Geophys. 2021, 18, 499–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Project | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Transmitting coil radius (m) | 0.2 | Weak magnetic small loop |

| Transmitting coil turns (turn) | 10 | / |

| Receiving coil radius (m) | 0.6 | / |

| Receiving coil turns | 100 | / |

| Sampling frequency (MHz) | 25 | / |

| Excitation current (A) | 20 | / |

| Excitation voltage (V) | 12 | / |

| Sampling time (ms) | 25 | 40 logarithmically equally spaced |

| Excitation waveform | / | Bipolar pulse square wave |

| Formation resistivity distribution | Variation with depth | / |

| Stratum thickness distribution | Variation with depth | / |

| Simulated dataset | 2000 | / |

| Measured dataset | 800 | / |

| Validation dataset | 200 | / |

| Number of Hidden Layer Nodes | 16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 256 |

| ERMS (Ω·m) | 19.70 | 19.80 | 19.40 | 19.60 | 19.50 |

| Hyperparameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of LSTM hidden layer nodes | 64 |

| Number of Bi-LSTM layers | 3 |

| Batch size | 40 |

| Optimizing functions | Adam |

| Learning Rate | 0.001 |

| Dropout | 0.01 |

| Model Variant | R2 | ERMS (Ω·m) | EMR (Ω·m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| IE-CBiLSTM | 0.864 | 17.63 | 0.064 |

| CNN-BiLSTM | 0.809 | 21.48 | 0.093 |

| Informer-BiLSTM | 0.816 | 20.73 | 0.087 |

| Informer-CNN | 0.823 | 19.85 | 0.082 |

| Inversion Method | R2 | ERMS (Ω·m) | EMR (Ω·m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MWO-Elman | 0.367 | 38.42 | 0.287 |

| BPNN | 0.358 | 37.61 | 0.249 |

| SDM-ANN | 0.474 | 31.35 | 0.223 |

| Occam | 0.729 | 26.49 | 0.157 |

| LSTM | 0.765 | 20.37 | 0.087 |

| IE-CBiLSTM | 0.861 | 17.54 | 0.061 |

| Target Depth (m) | Mean Inverted Depth (m) | 95% Confidence Interval (m) | Number of Tests |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | 1.02 | [0.99, 1.05] | 5 |

| 1.2 | 1.19 | [1.16, 1.22] | 5 |

| 1.5 | 1.48 | [1.45, 1.51] | 5 |

| Inversion Method | R2 | ERMS (Ω·m) | EMR (Ω·m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Occam | 0.581 | 31.67 | 0.180 |

| LSTM | 0.792 | 25.54 | 0.128 |

| IE-CBiLSTM | 0.933 | 11.30 | 0.046 |

| Aspect | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Inversion Model (IE-CBiLSTM) | High Accuracy: Superior inversion accuracy and low error in field tests Strong Robustness: Excellent noise resistance in complex electromagnetic environments Automation and Efficiency: Fast prediction speed Good Interpretability: Model architecture aligns with PEC physics | Data Dependency: Requires substantial training data Computational Cost: Training requires GPU resources Model Complexity: Requires careful hyperparameter tuning Black-Box Nature: Decision path not fully transparent |

| Detection Device and Methodology | Non-Destructive: No excavation required Portable: Designed for field use with portable power supply Integrated Positioning: GPS for spatial data tagging Visualization Capability: Generates 3D inversion maps | Limited Detection Depth: Effectiveness decreases for deep conductors Site Sensitivity: Affected by extreme soil conditions Surface Access Required: Needs direct ground contact Coil Orientation Sensitivity: Accuracy depends on proper alignment |

| General Applicability | Promising Engineering Utility: Reliable strategy for grounding grid testing | Task-Specific Design: Optimized for depth inversion only |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yue, Y.; Xu, S.; Fan, Y.; Tian, X.; Liu, X.; Hu, X.; Wang, J. Design and Validation of a CNN-BiLSTM Pulsed Eddy Current Grounding Grid Depth Inversion Method for Engineering Applications Based on Informer Encoder. Designs 2025, 9, 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs9060128

Yue Y, Xu S, Fan Y, Tian X, Liu X, Hu X, Wang J. Design and Validation of a CNN-BiLSTM Pulsed Eddy Current Grounding Grid Depth Inversion Method for Engineering Applications Based on Informer Encoder. Designs. 2025; 9(6):128. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs9060128

Chicago/Turabian StyleYue, Yonggang, Su Xu, Yongqiang Fan, Xiaoyun Tian, Xunyu Liu, Xiaobao Hu, and Jingang Wang. 2025. "Design and Validation of a CNN-BiLSTM Pulsed Eddy Current Grounding Grid Depth Inversion Method for Engineering Applications Based on Informer Encoder" Designs 9, no. 6: 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs9060128

APA StyleYue, Y., Xu, S., Fan, Y., Tian, X., Liu, X., Hu, X., & Wang, J. (2025). Design and Validation of a CNN-BiLSTM Pulsed Eddy Current Grounding Grid Depth Inversion Method for Engineering Applications Based on Informer Encoder. Designs, 9(6), 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs9060128