Abstract

The growth in the prevalence of dementias is associated with a phenomenon that challenges the 21st century, population aging. Dementias require physical and mental effort on the part of caregivers, making it difficult to promote controlled and active care. This review aims to explore the usability and integration of wearable devices designed to measure the daily activities of elderly people with dementia. A survey was carried out in the following databases: LILACS, Science Direct and PubMed, between 2018 and 2024 and the methodologies as well as the selection criteria are briefly described. A total of 27 articles were included in the review that met the inclusion criteria and answered the research question. As the main conclusions, the various monitoring measurements and interaction aspects are critically important, demonstrating their significant contributions to controlled, adequate and active monitoring, despite the incomplete compliance with the key aspects which could guarantee solutions economically accessible to institutions or other organizations through the application of the design requirements. Future research should not only focus on the development wearable devices that follow the essential requirements but also on further studying the needs and adversities that elderly people with dementia face as a pillar for the development of a feasible device.

1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), today’s society is witnessing a marked demographic transformation worldwide, with implications for various sectors. In quantitative terms, the number of elderly people is expected to double by the year 2050, from 962 million (2017) to 2.1 billion, respectively [1]. Therefore, this demographic change is associated with increased longevity, a result of improved healthcare and living conditions over the last few decades [2]. Nevertheless, it is crucial to promote awareness and concern about this phenomenon and the challenges it poses on both a socioeconomic and cultural level for society in general [3]. Additionally, it is highlighted that the greater the number of elderly people, the more it negatively affects the productivity growth of economies; therefore, it is necessary to adopt more sustainable political decisions that ensure the sustainability of the current situation [3]. Even so, the United Nations argues that elderly people are a great contribution to the development of new policies and appropriate programs, as the implementation of appropriate approaches allows for the structuring of a political commitment, which ensures the integration of population aging in the process of development [4]. Thus, social inclusion is promoted, which influences the reduction in stigma and discrimination of a highly vulnerable social group.

Given this demographic change, the pattern of disease prevalence also changes, focusing, in this case, on cognitive impairment diseases [5]. This is due to increasing age being one of the main factors in the development of these diseases. Among the various diseases, dementia is the one that presents significant effects with high emotional and financial costs. The prevalence of elderly with dementia (EwD), follows the growth of the elderly population and it is expected that the number of cases will continue to increase [6].

According to the WHO, there are currently 55 million people with dementia and each year, there are around 10 million new cases. Additionally, dementia is the seventh leading cause of death and one of the main causes of disability and dependence among the world’s elderly population [7]. In view of this, dementia affects one to several cognitive domains, from loss of memory, language, problem solving and tasks, and other skills that are present in an individual’s daily routine [8]. Therefore, these people quickly depend, from a very early age, on a social group that has accompanied the growth of dementia, the caregivers (CGs).

CGs play a fundamental role in the care of EwD, helping to perform daily activities (instrumental activities, managing finances, administering medication, and attending to behavioral and psychological symptoms) [9]. However, the role of the caregiver can often be a great challenge, providing a feeling of insufficiency and guilt in the work they do, anxiety about the worsening of the disease, among others. Faced with this situation, the long-term CG ends up harming the quality of care for the elderly and themselves [9].

In this sense, it is important to find new solutions or strategies that help both EwD and their CGs/family members in carrying out daily activities or, at least, improving their treatment with information provided about daily tasks [10]. On the other hand, the help provided to CGs can also be through tools or products that help monitor and facilitate dementia treatment. In this way, design can be introduced as a support tool and procedure to assist in recognizing and understanding the specific needs that this target audience faces, translating them into requirements for designing adapted interventions and systems [11]. Given this, it is possible to achieve a daily monitoring solution and contribute to a better quality of life for EwD and their CGs.

In view of this, this review sought to understand the wearable devices (WDs) developed to date that can monitor the daily activities of EwD, as well as carry out an analysis of the design aspects present in them. Subsequently, we intended to bring together these aspects to create an overview of the design requirements that can influence and lead to designing the ideal WD for EwD.

The results of this review not only serve as a basis for future studies of WDs but also consider the implementation of appropriate requirements and measures that respond to the adversities of EwD and their caregivers.

This article is organized in five sections: Section 2, “Methodology”, describes the systematic review methodology and process used. Section 3, “Results”, presents the results obtained, starting with a brief overview of the context of the review, addressing technology in the health and wellness sector, the evolution of WDs, and their identification and classification. This is followed by a presentation of the role that design has played in the health sector and how it has had an impact using different design methodologies. Subsequently, based on these methodologies and the studies analyzed, the design requirements for the projection of a WD for EwD are defined. Section 4, “Discussion”, is based on the discussion of the results obtained above, with a comprehensive analysis of both the technological functionalities that the ideal WD should have and a comparison between them in the WDs included in the study, as well as a convergent study of the defined design requirements of the same WDs. This was followed by a final assessment of the results obtained, resulting in a diagram of the design requirements. Finally, Section 5, “Conclusions and Future Works”, presents the final considerations and observations of the review and future perspectives for both the development of new WDs and possible new design requirements.

2. Methodology

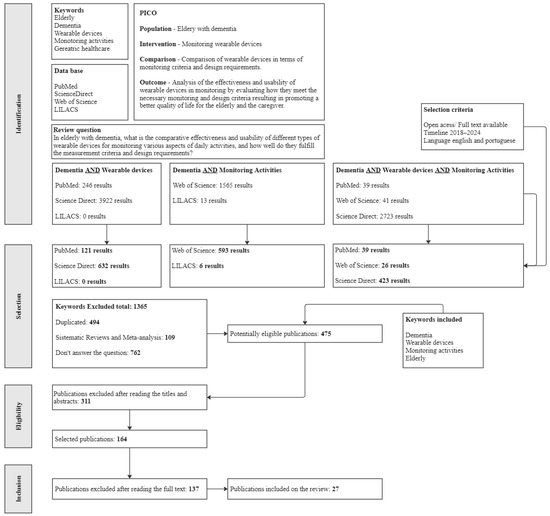

This review began with the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and the review article “Steps in Conducting a Systematic Review” based on the same handbook [12,13]. These recommendations made it possible to establish the formulation of the research question and the inclusion and exclusion criteria. In addition, these helped with the selection of studies, analysis, and presentation of the results through a detailed search and the drawing of conclusions. This review also included an exploration of resources associated with the design requirements for the same context and experiences by the target audience and their caregivers. Figure 1 presents the steps performed in the literature review.

Figure 1.

Literature search flow diagram.

2.1. Search Strategy

The PICO strategy (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes) was adopted, helping to define the research question to be answered. In this way, the EwD are the population under study, focusing on their needs and difficulties (P), the intervention being studied (I) is the use of WDs to monitor various aspects of the health and well-being of the EwD, including the analysis of the functionalities and capabilities of WDs in responding to the needs of the target audience. The analysis and comparison (C) are about the different types of WDs, and their performance in meeting the monitoring criteria for EwD, as well as the design requirements in the WDs. The outcome (O) encompasses the conclusions related to the effectiveness and usability of WDs in monitoring EwD by assessing how the WDs meet the necessary monitoring and design criteria. Additionally, the identification of future research perspectives and improvements were also included.

Thus, the question that led to the study was as follows: In EwD, what is the comparative effectiveness and usability of different types of WDs for monitoring various aspects of daily activities, and how well do they fulfill the measurement criteria and design requirements?

2.2. Keywords and Databases

To ensure a more precise search, fixed keywords were used to search for studies: Elderly, Dementia, Wearable devices, Monitoring activities, Geriatric healthcare. The Boolean operator “AND” was also used to combine the terms Dementia “AND” Wearable devices, Dementia “AND” Monitoring and Dementia “AND” Wearable devices “AND” Monitoring Activities.

In order to carry out a rigorous systematic review, four different databases were used: PubMed, ScienceDirect, Web of Science and LILACS. The combination of the terms Dementia “AND” Wearable devices was used in PubMed, Science Direct and LILACS, while the combination of Dementia “AND” Wearable devices “AND” Monitoring Activities was used in Web of Science and LILACS. Finally, the combination of the terms Dementia “AND” Monitoring Activities and Dementia “AND” Wearable devices “AND” Monitoring Activities was used in PubMed, Web of Science and Science Direct databases, making it possible to obtain a wide variety of combinations of studies.

2.3. Selection Criteria

The selection criteria are divided into four phases so that they are organized in a structured way, demonstrating the entire process of exploration and detailed research carried out. Before starting the first phase, the databases were searched for combinations of the terms mentioned above. For the combination of Dementia AND Wearable devices, PubMed obtained 246 results, Science Direct 3922 results, and LILACS 0 results. In the combination of Dementia “AND” Monitoring Activities, Web of Science found 1565 results and LILACS 13 results and, finally, in the combination of Dementia “AND” Wearable devices “AND” Monitoring Activities, PubMed obtained 39 results, Web of Science 41 results and Science Direct 2723 results.

After this, the first phase began, where the same filters were applied to all databases, restricting the year range between 2018 and 2024, the language of the articles to English and Portuguese, and full access to the articles.

When combining the terms Dementia “AND” Wearable devices, PubMed obtained 121 results, Science Direct 632 results, and LILACS 0 results. When combining Dementia “AND” Monitoring Activities, Web of Science obtained 593 results and LILACS 6 results. Finally, for the combination of Dementia “AND” Wearable devices “AND” Monitoring Activities, PubMed obtained 41 results, Web of Science 26 results and Science Direct 423 results.

In a second phase, the following exclusion keywords were applied: duplicate articles (n = 494), systematic reviews and meta-analysis (n = 109) and articles that did not answer the review question (n = 762). As a result, a total of 1365 articles were excluded according to the exclusion keywords, resulting in 475 potentially eligible publications.

In the third phase, articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded after reading the titles and abstracts (n = 311): Dementia; Wearable devices; Monitoring activities; Elderly. Thus, 164 publications were selected for the last phase.

In the fourth and final phase, the text of the publications was read in full, and 137 articles were excluded, leaving 27 publications included in this review.

2.4. Description of Studies

This subsection provides a detailed description of the studies carried out using the selected articles. In this way, it is possible to ensure coherence between the methodology of the work and its results, facilitating a clear understanding of the research process and its outcomes.

The studies will be based on two main parts: Study 1: a comparative study of the technical specifications present in WDs of the chosen articles resulting from the methodological process described above; Study 2: an analytical study of the different fundamental design criteria in WDs for the target audience in question. In this way, both studies will have a similar purpose: to identify the essential requirements or guidelines for designing an ideal wearable device for measuring the daily activities EwD.

The Section 3 provides a detailed description of the studies in each part, as well as the statistical methods applied.

Study 1 will carry out comparative studies of different measurement methods, specific measurement data that each device contains, and its main results framed in the articles. Therefore, Study 1 will cover the articles presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Included articles in Study 1.

Study 2 will study the requirements and recommendations that investigate design as a tool for promoting better interaction with users. These requirements will be based on the same principles, which are the principles of Universal Design. Therefore, Study 2 will cover the articles presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Included articles in Study 2.

3. Results

3.1. Technology in Healthcare

Recent advances in technological innovation, particularly in the development of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) and Assistive Technology (AT), have given opportunities to reconstruct and assist in the care of EwD [10]. These technological devices not only focus on assisting the activities of daily living but also help alleviate the financial burden that dementia treatments entail. Furthermore, the implementation of these devices contributes to reducing the burden and anguish on the part of formal and informal CGs as it allows for adequate and controlled monitoring of the pathology. All these aspects result in a better quality of life for both the CG and the EwD.

Given that these technologies perform these functions, there is a need to have a consensus between a functional product and a product suitable for the user, that is, devices must contain a design that is centered and acceptable to EwD. To achieve this, it is necessary to recognize the difficulties they face and the fact that they are a highly complex social group when developing a product that will not only be part of the daily routine but with which they will also have direct interaction [41].

3.2. Wearable Devices

The evolution of WDs for healthcare has remained an alternative to conventional applications and support tools, as many studies show great potential when it comes to providing monitored care [44]. Such monitoring is committed to minimal intrusion, high battery life, obtaining various measurement data, continuous monitoring, an approach focused on the type of users and intuitive interaction [44]. A WD can be incorporated into the body or not, and ranges from smart bracelets, rings, belts, necklaces, glasses, watches, earphones, headbands, to clothing with built-in sensors [45].

In the scenario of monitoring EwD as the pathology gradually worsens, interaction with everyday products becomes increasingly challenging. In view of this, WDs aim to facilitate this difficulty and control the progression and state of dementia through a User-Centered approach [42]. For such an approach, it is not only extremely important to establish support functionalities, but also to design a WD that can be used intuitively and establishes an easy and dynamic interaction with the user.

In Table 3, descriptive statistics were used as a method corresponding to a qualitative analysis in order to encompass the core technical specifications of the WDs in each study included. The variables analyzed were as follows: product; source; measurement method; company; and device placement. All this information is divided by each WD.

Table 3.

Technical specifications of wearable devices used in individual studies.

Classification of Monitoring Types in Wearable Devices

Most WDs used in healthcare have activity monitoring as their main functionality. These can encompass a broad measurement of an individual’s data through sensors capable of measuring heart rate, daily behaviors, sleep patterns, stress level, movements, location, among others.

In the present study, 3 of the 25 articles (12%) reported that the results obtained from daily activities were measured by Actigraphy. Also, 52% of the selected articles showed that they collected data through activity tracker sensors, these being the most common and present in the field of WDs. Regarding Accelerometers, which generally use three measurement axes, they are found in 16% of the selected articles. Another 12% correspond to WDs that had an integrated GPS system and the remaining 16% report that they obtained activity data through Photoplethysmography [22], Inertial sensors [24], Electroencephalography [19] and Photodiode [39].

Table 4 also shows the use of descriptive statistics, regarding the frequency measure (count/percentage of WDs containing certain measurements) with the following variables: wearable device; daily activity; daytime activity; night-time activity; activity patterns; movement patterns; real-time location; fall detection; and SOS warning. All these specific measures are divided by each WD.

Table 4.

Specific outcome measures of daily activity reported by included studies.

3.3. Specific Measurements of Wearable Devices

WDs are equipped with technologies and sensors potentially capable of different measurements relevant to a person’s well-being. To develop an ideal WD, it is important to consider some monitorization aspects, in this case, when monitoring EwD. Therefore, the more relevant data the WD can capture, the more credible and well-founded the progressive monitoring of the pathology will be. In Table 2, we compare the different WDs; regarding these, it is important to consider that, in relation to daily monitoring, both during the day and at night, these allow for continuous and precise monitoring. Given this, around 72% of WDs measure activities daily. In the case of measuring night-time activities, 60% of WDs perform this measurement, which generally refers to monitoring sleep patterns, understanding how many times the elderly person was awake, their sleep quality and other patterns.

Regarding measuring activity and movement patterns, the collection of information on heart rate, breathing patterns, stress level, physical exercise and information on movements performed is included. These aspects have some emphasis, as these provide CGs with valuable insights into the well-being of EwD, promote adapted care, contribute to physical and emotional health, and offer a better quality of life for the EwD and the CG. These two criteria have a slight percentage difference between them, with more than half of the WDs containing these features.

In the case of WDs containing a real-time location system, only 20% have this aspect, which allows the CG to find out if the elderly person has left and where they are heading, mainly outside, caused by episodes of disorientation or memory loss. Fall detection only occurs in three of the selected WDs as it is a feature rarely found in these devices but of high importance, as the elderly may experience some unintentional accident or imbalance. In view of this, it is necessary to have some form of communication or urgent warning at the time to the CG that the elderly person has suffered this fall or other type of episode that requires urgent contact with the CG. It was found that only two of the WDs, one being related to fall detection [28], contained a button specifically for urgent contact, prominently displayed on the WD.

In Table 5, the authors analyze the main results and describe relevant characteristics of the studies included in this review using descriptive statistics as an analytical method. The variables studied were as follows: wearable device; source; study design; participants (n); and major findings.

Table 5.

Characteristics and major findings of included studies.

In this way, they were able to establish a clearer perspective of the impact of integrating WDs, both in terms of data collection and measurement and interaction with users.

As such, it is generally understood that the majority of WDs had a positive effect on the lives of EwD, with these devices promoting self-care and well-being, resulting in improved sleep patterns and cognitive status.

The integration of these devices also served, in many studies, as a non-invasive means of diagnosing and monitoring the progression of various dementias and the cognitive status of individuals. Once these data are detected, treatment or interventions tailored to the needs of the EwD can be ensured.

In addition, many studies have shown great acceptance and satisfaction by EwD when using a WD, on the wrist, for more than 24 h not only because of the familiar design (i.e., identical to what appears to be a conventional watch) but the high level of comfort too. On the other hand, when it came to EwD in more advanced stages or when the devices were intended to be worn elsewhere than on the wrist, they were easily discarded, resulting in an incomplete assessment of the health condition.

3.4. Design in Healthcare

In the context of design for healthcare, just as functional criteria play an important role, it is crucial to highlight that there are studies that show that there is a need to improve the interaction between products and people with dementia since the relationship between the two becomes increasingly complex [41]. In view of this, there is a need to look for well-structured information on how design can be a means to design products with an appropriate approach to a group of vulnerable users. The studies present guidelines and parameters that are indispensable in the development of a product for EwD and the majority are based on already known design approaches, such as Universal Design and User-Centered Design, as these mainly value accessibility for everyone [42].

The Centre for Excellence in Universal Design states that Universal Design is a concept that serves as a process of making products accessible and usable by everyone without the need to adapt or specialize the design [46]. These should cater to the largest sample of people possible, without considering gender, race, health condition or disability, or other factors that may be relevant [46].

The Centre for Excellence in Universal Design defines the seven principles of Universal Design that aim to constitute a series of essential parameters aimed at designing products, services, and environments, allowing for the greatest number of users represented in the Table 6 [47].

Table 6.

The seven principles of Universal Design, adapted from [47].

The Universal Design Manual for Health Services shows the importance of implementing Universal Design benefits in several aspects, such as the following [48]:

- Promotes independence;

- Advances mobility and social inclusion;

- Increase everyone’s quality of life, without devaluing anyone’s;

- Reduces stigma and discrimination;

- Provides more opportunities for vulnerable social groups;

- Guarantees a more comfortable, attractive, accessible, convenient and safe world for all users;

- Reduces the economic burden of specialized programs and services that help people from specific social groups;

- Creates an inclusive society with knowledge of the diversity of society, ensures equality and inclusion on equal terms;

- Promotes respect for the capabilities of all people.

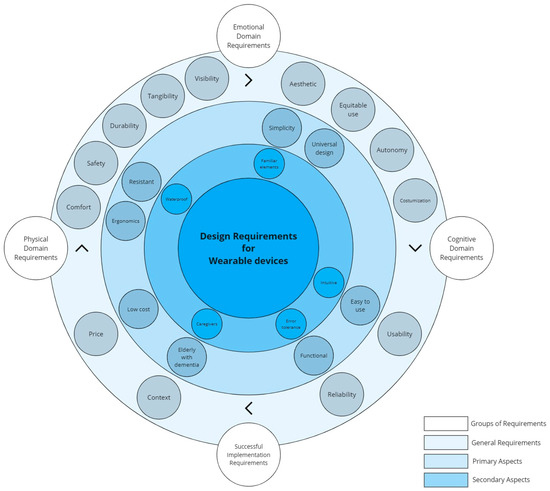

3.5. Defining Design Requirements

The aforementioned studies explore a wide variety of design recommendations, from the most general to the most specific, and they were structurally encompassed in order to connect different requirements to different categories. In this way, four categories were defined based on the analysis of the underlying design recommendations, these being physical, emotional, cognitive, and contextual.

The main focus of defining these requirements is to make it easier for the product to interact with the user, which is the recommendation most often found in studies and has a high impact on the emotional well-being of EwD [41]. In addition, another recommendation that has been verified more than any other is the proper appreciation of the social group’s context for the successful implementation of the respective product [41]. In other words, there is a greater need to understand the needs of older people living with the disease, helping to include them in decisions about services and products.

Defining these requirements not only aims to provide a better relationship between users and the product and more active care, but also helps in the future development of WDs that address the same causes, guaranteeing a successful methodological process as well as implementation.

3.5.1. Physical Domain Requirements

As far as physical requirements are concerned, they usually aim to cover the general ergonomics of a given product, i.e., an ergonomic and anthropometric study is carried out so that it meets basic needs when used. In this case, since we are considering WDs for monitoring, it is important to carry out a preliminary analysis of the potentially ideal product for EwD since this is a social group with high vulnerability and sensitivity (Table 7).

Table 7.

Physical domain requirements and their description.

3.5.2. Emotional Domain Requirements

These requirements are responsible for the emotional relationship between the product and the user, addressing more ethical and visual issues, without devaluing the physical characteristics (Table 8).

Table 8.

Emotional domain requirements and their description.

3.5.3. Cognitive Domain Requirements

The cognitive domain requirement criteria are based on understanding users’ cognitive abilities and needs, particularly in EwD, ensuring that the WDs are truly useful (Table 9).

Table 9.

Cognitive domain requirements and their description.

3.5.4. Successful Implementation Requirements

For a successful implementation of the WD, even fulfilling the physical, emotional, and cognitive domain requirements, there is one aspect that should not be overlooked when designing any type of product for EwD. This is not to forget the integration of context into the development of the product, in this case, the inclusion of EwD, guaranteeing the effectiveness, acceptance and benefit of WD (Table 10).

Table 10.

Successful implementation requirements and their description.

4. Discussion

In the present discussion of the results, in order for it to be understood in a way that is consistent with the results obtained, the descriptive statistics method was used with regard to the frequency measure (count/percentage of articles that meet a certain requirement). In this case, it was regarding design requirements, whether in the physical, emotional, cognitive or implementation success domains.

This systematic review yielded 27 articles that met the inclusion criteria for WDs for monitoring daily activities in EwD.

It is known that the ideal WD should hold the maximum amount of data from daily activities and meet the design requirements presented. However, none of the 27 WDs included in the study meet the eight criteria set out in Table 4, with the Microsoft Band [31] being the only WD to meet seven of them.

However, 55% of the WDs included only minimally fulfill this function, with three of the eight criteria, measuring the daily activities, daytime activities and activity patterns.

As far as design requirements are concerned, around 85% of the WDs included are prone to being easily removed, as they contain a familiar placement system, making it an unsafe system. On the other hand, since 70% of WDs have a conventional insertion and removal system, it has the possibility of being adaptable and usable by a greater number of users. This is since the component is adjustable in size, which subsequently promotes comfort in daily use.

Regarding the fact that WDs are designed for EwD, only 37% of those included contain physical elements of manual interaction with differentiated prominence, and only two of all WDs have a manual component with a different color, size and shape aimed at warnings in urgent situations. These aspects are extremely important given that this is a social group with several disabilities, not only due to pathology but also due to the factor of old age, and that it is essential to have clear and visible visual elements.

The requirement of esthetics will always be a subjective one; however, when discarding the WDs that are not for use on the wrist [19,22,24,33,34,35], they contain a very familiar visual design, appearing to be everyday watches or bracelets. The fact that some of the WDs have a display promotes autonomy, as they feel they can still perform actions without depending on CGs, such as checking the time, heart rate, daily physical activity, among others.

Still on this topic, the WDs that are not placed on the wrist or arm become WDs that do not have minimally invasive monitoring. In other words, the fact that they are to be placed in less common and more invasive places, such as around the torso, neck, or ear, ends up restricting their place of use and can create a relationship of discomfort and opposition. For example, in elderly women, the fact that the WD is placed in the ear means that they cannot wear earrings, which is an accessory that often gives them greater self-esteem and self-confidence. Furthermore, in the context of the pathology they experience, the place where they wear them is not the most appropriate and is very visible, giving them a feeling of inferiority due to the pathology they have. In the case of the elderly, it is common for hearing to deteriorate, contributing to the use of hearing aids. However, the place where the WD is placed can conflict with the use of these aids, preventing them from being used and further reducing hearing.

Finally, only 11% of the WDs did not directly integrate EwD into their studies, and therefore did not value them in the implementation of the WD. Nevertheless, the balance of this requirement is very positive, with more than half of the studies included having included the EwD, obtaining true activity benchmarking feedback for future successful implementation.

Design Requirements Diagram

A diagram (Figure 2) that covers all the fundamental design requirements for WDs intended for EwD present in Table 7, Table 8, Table 9 and Table 10 was developed. Its main objective is to provide a structured organization and concrete understanding of the fundamental requirements for the success of the WD.

Figure 2.

Circular diagram of design requirements for wearable devices.

This diagram not only lays out the respective requirements, but also shows how each one relates to and influences the others. In this way, it is possible to highlight the interdependence of each WD design requirement. For example, the familiar elements belonging to esthetics can directly affect the usability of the WD, particularly helping with the intuitiveness and ease to use of the WD.

By considering the relationships established in a concise manner, it becomes clear that each decision made in relation to one requirement can have significant ramifications for other aspects of the WD. Therefore, considering the requirements together guarantees the development of a WD that is ergonomically appropriate, esthetically pleasing, functional and, above all, compliant with the needs of the EwD.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

In conclusion, this review offers a wide range of information that addresses not only the various monitoring measurements present in the WDs included in the study, but also highlights their individual and collective importance. The in-depth analysis reveals how the respective measurements play crucial actions in a more controlled and active monitoring of the EwD, ensuring the well-being of the EwD as well as that of the CGs.

In general, the WDs featured in the article achieve minimally complete monitoring despite the fact that none of them strictly comply with all the measurement criteria. On the other hand, as many of the WDs have been discontinued, it was not possible to obtain complete information on the type of measurement they performed.

Furthermore, the fact that the ideal design requirements for designing a monitoring WD aimed for EwD have been defined does not imply that they are entirely complete. New requirements can be added with future in-depth studies into the needs of this target audience. The importance of the Universal Design and User-Centered Design approaches in helping to devise the most appropriate requirements should not be overlooked, as they advocate equal accessibility for all.

By relating the analysis of the various activity measurements and the design requirements, it is clear that, in general, WDs stand out positively. Just as each type of measurement can measure an activity that needs to be monitored and followed up, each design requirement can help to monitor and meet one or more specific EwD needs.

Therefore, this review not only provides a comprehensive overview of the different WDs and their capabilities, but also highlights their importance at the intersection of technology, design, and health. This intersection strongly contributes to future developments that are better able to respond to the needs and adversities that both EwD and their CGs face on a daily basis.

For future work, it is recommended to continue exploring specific data measurement methods that help monitor dementia pathology, which is compromised by various factors. In addition, continuous analysis of the adversities that EwD face and how these may worsen is recommended so that the WD is prepared for these changing patterns and adapts to the state of dementia, promoting improved effectiveness, impact on health, and the well-being of EwD. Furthermore, clinical and practical studies will be carried out in the future, considering them in conjunction with the target population as well as the device to be developed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.C.R., M.A., A.M., J.L.V., P.M., D.M. and V.C.; methodology, I.C.R., J.L.V., P.M., D.M. and V.C.; validation, I.C.R., M.A., A.M., J.L.V., P.M., D.M. and V.C.; formal analysis, I.C.R., M.A., A.M., J.L.V., P.M., D.M. and V.C.; investigation, I.C.R., M.A., A.M., J.L.V., P.M., D.M. and V.C.; resources, A.M., J.L.V., P.M., D.M. and V.C.; writing—original draft preparation, I.C.R., M.A., P.M., D.M. and V.C.; writing—review and editing, I.C.R., M.A., A.M., J.L.V., P.M., D.M. and V.C.; visualization, I.C.R., M.A., A.M., J.L.V., P.M., D.M. and V.C.; supervision, A.M., J.L.V., P.M., D.M. and V.C.; project administration, A.M., J.L.V., P.M., D.M. and V.C.; funding acquisition, A.M., J.L.V., P.M., D.M. and V.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Innovation Pact HfFP—Health From Portugal, co-funded by the “Mobilizing Agendas for Business Innovation” of the “Next Generation EU” program of Component 5 of the Recovery and Resilience Plan (RRP), concerning “Capitalization and Business Innovation”, under the Regulation of the Incentive System “Agendas for Business Innovation”. This project was also funded through the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) under the projects UIDB/05549/2020 (DOI: 10.54499/UIDB/05549/2020), UIDP/05549/2020 (DOI: 10.54499/UIDP/05549/2020, CEECINST/00039/2021 and LASI-LA/P/0104/2020.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the partners OneCare, Centro de Medicina Digital P5, and The Clinical Academic Center of Braga (2CA-Braga) for the support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| EwD | Elderly with Dementia |

| CG | Caregiver |

| WD | Wearable Device |

| ICT | Information and Communications Technology |

| AT | Assistive Technology |

References

- World Health Organization: Ageing and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). Annual Report 2012 Promises to Keep; UNFPA: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Virginia, S.; Areosa, C.; Luiz Areosa, A. Aging and dependence: Challenges to be faced. Textos Contextos 2008, 7, 138–150. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). Ageing. Available online: https://www.unfpa.org/ageing (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Santana, I.; Farinha, F.; Freitas, S.; Rodrigues, V.; Carvalho, Á. The Epidemiology of Dementia and Alzheimer Disease in Portugal: Estimations of Prevalence and Treatment-Costs. 2015. Available online: www.actamedicaportuguesa.com (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Maria Azevedo Dos, S.; Rifiotis, T. Cuidadores Familiares de Idosos Dementados: Uma Reflexão Sobre a Dinâmica do Cuidado e da Conflitualidade Intra-Familiar. 2006. Available online: http://www.cfh.ufsc.br/~levis/Cuidadores%20Familiares%20de%20Idosos%20Dementados.htm (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- World Health Organization, “Dementia,” 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s and Dementia. Available online: https://www.alz.org/alzheimer_s_dementia (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Maria Pires Camargo Novelli, M.; Nitrini, R.; Caramelli, P.; Paulo-Campus Baixada Santista, S.; Associado, P. Caregivers of Elderlies with Dementia: Their Social and Demographic Profile and Daily Impact; Revista De Terapia Ocupacional Da Universidade De São Paulo: São Paulo, Brazil, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ienca, M.; Fabrice, J.; Elger, B.; Caon, M.; Pappagallo, A.S.; Kressig, R.W.; Wangmo, T. Intelligent Assistive Technology for Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias: A Systematic Review. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2017, 56, 1301–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, J.D.; Morais, P.; Carvalho, V. Routine Measurement and Monitoring System for the Activity of Elderly People with Dementia: A Systematic Review. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Sensors and Electronic Instrumentation Advances (SEIA’ 2023), Funchal, Portugal, 20–22 September 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.; Welch, V. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donato, H.; Donato, M. Etapas na Condução de uma Revisão Sistemática. Acta medica Port. 2019, 32, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donahue, E.K.; Venkadesh, S.; Bui, V.; Tuazon, A.C.; Wang, R.K.; Haase, D.; Foreman, R.P.; Duran, J.J.; Petkus, A.; Wing, D.; et al. Physical activity intensity is associated with cognition and functional connectivity in Parkinson’s disease. Park. Relat. Disord. 2022, 104, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au-Yeung, W.M.; Miller, L.; Beattie, Z.; Dodge, H.H.; Reynolds, C.; Vahia, I.; Kaye, J. Sensing a problem: Proof of concept for characterizing and predicting agitation. Alzheimer’s Dement. Transl. Res. Clin. Interv. 2020, 6, e12079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, R.; Dowell, A.; Jones, L.; Gander, P. Non-pharmacological interventions a feasible option for addressing dementia-related sleep problems in the context of family care. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2021, 7, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, E.; Jiang, J.; Su, R.; Gao, M.; Zhu, S.; Zhou, J.; Huo, Y. A new smart wristband equipped with an artificial intelligence algorithm to detect atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm 2020, 17, 847–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winer, J.R.; Lok, R.; Weed, L.; He, Z.; Poston, K.L.; Mormino, E.C.; Zeitzer, J.M. Impaired 24-h activity patterns are associated with an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and cognitive decline. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2024, 16, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Li, J.; Zhang, D.; Wu, W.; Zhao, J.; Qiang, Y. Synergy through integration of digital cognitive tests and wearable devices for mild cognitive impairment screening. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1183457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godefroy, V.; Levy, R.; Bouzigues, A.; Rametti-Lacroux, A.; Migliaccio, R.; Batrancourt, B. Ecocap-ture@home: Protocol for the remote assessment of apathy and its everyday-life consequences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iaboni, A.; Spasojevic, S.; Newman, K.; Martin, L.S.; Wang, A.; Ye, B.; Mihailidis, A.; Khan, S.S. Wearable multimodal sensors for the detection of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia using personalized machine learning models. Alzheimer’s Dement. Diagn. Assess. Dis. Monit. 2022, 14, e12305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, J.-W.; Choi, J.; Lee, K.; Kim, J.U. Age-related changes in the characteristics of the elderly females using the signal features of an earlobe photoplethysmogram. Sensors 2021, 21, 7782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’sullivan, G.; Whelan, B.; Gallagher, N.; Doyle, P.; Smyth, S.; Murphy, K.; Dröes, R.; Devane, D.; Casey, D. Challenges of using a Fitbit smart wearable among people with dementia. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2023, 38, e5898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pau, M.; Mulas, I.; Putzu, V.; Asoni, G.; Viale, D.; Mameli, I.; Leban, B.; Allali, G. Smoothness of gait in healthy and cognitively impaired individuals: A study on Italian elderly using wearable inertial sensor. Sensors 2020, 20, 3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, J.; Boyle, J.; Pretzer-Aboff, I.; Knoefel, J.; Young, H.M.; Wheeler, D.C. Using a GPS watch to characterize life-space mobility in dementia: A dyadic case study. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2021, 47, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farina, N.; Sherlock, G.; Thomas, S.; Lowry, R.G.; Banerjee, S. Acceptability and feasibility of wearing activity monitors in community-dwelling older adults with dementia. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2019, 34, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godkin, F.E.; Turner, E.; Demnati, Y.; Vert, A.; Roberts, A.; Swartz, R.H.; McLaughlin, P.M.; Weber, K.S.; Thai, V.; Beyer, K.B.; et al. Feasibility of a continuous, multi-sensor remote health monitoring approach in persons living with neurodegenerative disease. J. Neurol. 2021, 269, 2673–2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Megges, H.; Freiesleben, S.D.; Rösch, C.; Knoll, N.; Wessel, L.; Peters, O. User experience and clinical effectiveness with two wearable global positioning system devices in home dementia care. Alzheimer’s Dement. Transl. Res. Clin. Interv. 2018, 4, 636–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Kowahl, N.R.; Rainaldi, E.; Burq, M.; Munsie, L.M.; Battioui, C.; Wang, J.; Biglan, K.; Marks, W.J.; Kapur, R. Wrist-worn sensor-based measurements for drug effect detection with small samples in people with Lewy Body Dementia. Park. Relat. Disord. 2023, 109, 105355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, T.; Pigliautile, M.; Águila, O.; Arambarri, J.; Christophorou, C.; Colombo, M.; Constantinides, A.; Curia, R.; Dankl, K.; Hanke, S.; et al. User experience and acceptance of a device assisting persons with dementia in daily life: A multicenter field study. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2022, 34, 869–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawtaer, I.; Mahendran, R.; Kua, E.H.; Tan, H.X.; Lee, T.-S.; Ng, T.P. Early detection of mild cognitive impairment with in-home sensors to monitor behavior patterns in community-dwelling senior citizens in Singapore: Cross-sectional feasibility study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e16854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seelye, A.; Leese, M.I.; Dorociak, K.; Bouranis, N.; Mattek, N.; Sharma, N.; Beattie, Z.; Riley, T.; Lee, J.; Cosgrove, K.; et al. Feasibility of in-home sensor monitoring to detect mild cognitive impairment in aging military veterans: Prospective observational study. JMIR Form. Res. 2020, 4, e16371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Ishii, S.; Matsuoka, A.; Tanabe, S.; Matsunaga, S.; Rahmani, A.; Dutt, N.; Rasouli, M.; Nyamathi, A. Perspectives of Japanese elders and their healthcare providers on use of wearable technology to monitor their health at home: A qualitative exploration. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2024, 152, 104691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freytag, J.; Mishra, R.K.; Street, R.L.; Catic, A.; Dindo, L.; Kiefer, L.; Najafi, B.; Naik, A.D. Using Wearable Sensors to Measure Goal Achievement in Older Veterans with Dementia. Sensors 2022, 22, 9923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyle, W.; Jones, C.; Murfield, J.; Thalib, L.; Beattie, E.; Shum, D.; O’dwyer, S.; Mervin, M.C.; Draper, B. Effect of a robotic seal on the motor activity and sleep patterns of older people with dementia, as measured by wearable technology: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Maturitas 2018, 110, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manley, N.A.; Bayen, E.; Braley, T.L.; Merrilees, J.; Clark, A.M.; Zylstra, B.; Schaffer, M.; Bayen, A.M.; Possin, K.L.; Miller, B.L.; et al. Long-term digital device-enabled monitoring of functional status: Implications for management of persons with Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. Transl. Res. Clin. Interv. 2020, 6, e12017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, J.; Forchhammer, B.H.; Maier, A.M. Adapting mobile and wearable technology to provide support and monitoring in rehabilitation for dementia: Feasibility case series. JMIR Form. Res. 2019, 3, e12346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campani, D.; De Luca, E.; Bassi, E.; Busca, E.; Airoldi, C.; Barisone, M.; Canonico, M.; Contaldi, E.; Capello, D.; De Marchi, F.; et al. The prevention of falls in patients with Parkinson’s disease with in-home monitoring using a wearable system: A pilot study protocol. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2022, 34, 3017–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saif, N.; Yan, P.; Niotis, K.; Scheyer, O.; Rahman, A.; Berkowitz, M.; Krikorian, R.; Hristov, H.; Sadek, G.; Bellara, S.; et al. Feasibility of Using a Wearable Biosensor Device in Patients at Risk for Alzheimer’s Disease Dementia. J. Prev. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2019, 7, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concheiro-Moscoso, P.; Groba, B.; Martínez-Martínez, F.J.; Miranda-Duro, M.d.C.; Nieto-Riveiro, L.; Pousada, T.; Pereira, J. Use of the Xiaomi Mi Band for sleep monitoring and its influence on the daily life of older people living in a nursing home. Digit. Health 2022, 8, 20552076221121162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesselink, R. Designing for dementia: An analysis of design principles. In Proceedings of the DRS2022, Bilbao, Spain, 25 June–3 July 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francés-Morcillo, L.; Morer-Camo, P.; Rodríguez-Ferradas, M.I.; Cazón-Martín, A. The Role of User-Centred Design in Smart Wearable Systems Design Process. In Proceedings of the DESIGN 2018 15th International Design Conference, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 21–24 May 2018; pp. 2197–2208. [Google Scholar]

- El Noshokaty, A.; El-Gayar, O.; Wahbeh, A.; Al-Ramahi, M.A.; Nasralah, T. Drivers and Challenges of Wearable Devices Use: Content Analysis of Online Users Reviews. In Proceedings of the Twenty-eighth Americas Conference on Information Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 10–14 August 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, H.S.; Exworthy, M. Wearing the Future—Wearables to Empower Users to Take Greater Responsibility for Their Health and Care: Scoping Review. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2022, 10, e35684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guk, K.; Han, G.; Lim, J.; Jeong, K.; Kang, T.; Lim, E.-K.; Jung, J. Evolution of Wearable Devices with Real-Time Disease Monitoring for Personalized Healthcare. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centre for Excellence in Universal Design. About Universal Design. Available online: https://universaldesign.ie/about-universal-design (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Centre for Excellence in Universal Design. The 7 Principles. Available online: https://universaldesign.ie/about-universal-design/the-7-principles (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP); Baida, L.; Ivanova, O. Universal Design in Healthcare Manual. Available online: https://ekmair.ukma.edu.ua/handle/123456789/18339 (accessed on 19 April 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).