1. Introduction

The public sector consists of several sections and services that are designed and utilised differently. For instance, design approaches to innovation in social care might be at variance with the techniques that are suitable for the design of efficient waste management services. Consequently, such variations in the structure and services of these public service systems demand different modes of interaction, relationship, co-design processes and design methods [

1]. Successful co-design processes have become an increasingly sensitive topic in the discipline of design and its fields of action, and perhaps even more critical in the public sector. Designers and facilitators who work with public sector spaces and services are encouraged to promote participatory actions and develop practices collaboratively, believing they create strong connections [

2]. The concept of co-design in terms of space and experience is a very wide field that includes, in turn, different methodologies to be put into practice: the main objective of the Hall of the Future project in terms of participatory design, is to promote a method of instrumentalisation related to a session of co-design conducted within the public sector.

The Hall of the Future project consists of upgrading and rethinking the spatial redistribution of the Salone Anagrafico of the Chamber of Commerce, Industry, Handicrafts and Agriculture of Milano, Monza and Lodi, with a future vision for the digitisation of services provided to citizens. The methodology applied to this research project was conceived by a team of researchers of the Department of Design, at the Politecnico di Milano, who, along with the involvement of students at the School of Design, have been able to establish an excellent collaboration with the Chamber of Commerce of Milano, Monza and Lodi and collect the key elements needed to continue towards a feasibility study for the realisation of the Hall of the Future project. The main work of the research team, including academics from different disciplines, was to monitor the various phases: a preliminary investigation; field research; systematisation and identification of the most promising project guidelines; elaboration of the project proposal chosen at the feasibility study level; and monitoring of the project realisation. The students were part of an interdisciplinary workshop and a course in the Product Service and System Design Master’s Degree, which meant they were temporary but fundamental actors in supporting the phases of research and investigation, and then in the conception of possible services to be included in the active plan of the Chamber of Commerce after submitting the feasibility project proposal.

It is not only immediately necessary to define a Public Building in an architectural manner, but also in a juridic one, since there are many different definitions we can adopt from different countries in the UE, but also around the world. It seems that the main differences are determined by the users: who can freely “permeate” that building.

“All over the world you encounter gradations of territorial claims with the attendant feeling of accessibility. Sometimes the degree of accessibility is a matter of legislation, but often it is exclusively a question of convention, which is respect by all”.

Hertzberger argued that “So-called public buildings such as the hall of the central post office or railway station may (at least during the hours that they are open) be regarded as street-space in the territorial sense.” He gave a list of examples of differentiated degrees of accessibility to the general public (the main element of the “accessibility grade” parameter) [

3], and this list, of course, can be extended to include other personal experiences:

College quadrangles in England, as in Oxford and Cambridge; the way they are accessible for everyone through porches, forming a sort of sub-system of pedestrian routes traversing the entire city center.

Public buildings, e.g., the hall of a post office, railway station, etc.

The courtyards of housing blocks in Paris, where a concierge usually reigns supreme.

Closed streets, to be found in different forms all over the world, sometimes patrolled by private security guards.

2. Participatory Design Meets Public Sector

In its initial form, participatory design was intended to steer the growth of technological development, particularly in the computerisation of workplaces. Since then, it has grown into a broader methodology that is applicable to all design aspects [

4]. Involving all stakeholders in every phase of the design process is the ultimate objective of participatory design. Designers, clients, users, the general public and other stakeholders are examples of stakeholders [

5]. When designing for the general public, users are instrumental stakeholders. It is valuable and acceptable to utilise participatory design to investigate and produce new designs since it focuses on the verbal interchange of design ideas, which is particularly crucial during the early conceptual phases of the design process. As a result of linguistic communication, both information and comprehension are gained [

6]. A participatory design process has the following objectives: “clarifying goals and needs, designing coherent visions for change, combining business-oriented and socially sensitive perspectives, initiating participation and partnerships with different stakeholders, using ethnographic analyses in the design process...and providing a large toolbox of different practical techniques” [

7]. Moreover, participatory design engenders a sense of ownership, engagement and, ultimately, the best outcomes for users. It may be accomplished in a number of ways, including workshops, ethnographic research, cooperative prototyping, mock-ups, cards and user design. During the workshops, stakeholders and designers collaborate to develop a shared vision, designs or even a basic grasp of the existing challenges in need of resolution [

5]. Organizing co-design sessions with stakeholders is one method to convert a project into a participatory one. Designers and design consultancies diversify their operations within the product innovation process by expanding into numerous value chain segments. Scenario development, trend books, cultural probes, creativity-aid toolkits, generative tools and product engineering, for example, are all products of a design process targeted at allowing creativity and innovation in all types of companies (including NGOs) [

8]. These design aids and tools are the physical components of accurate design-driven innovation processes that apply to both the public and private sectors. Indeed, there are several instances of advanced design processes in NGOs and the public sector that are focused on infusing design value into projects for the benefit of communities across a range of sectors, including public services, healthcare and social development [

9]. To obtain a sense of the scope of some of these initiatives, see the worldwide research network DESIS’s website (Design for Social Innovation and Sustainability). This broad range of design contributions is associated with project complexity; this includes when a design is concerned with the interaction of multiple factors, as in design for territories or design for cultural heritage projects, or when a design is concerned with complex projects for which the results will not be visible for an extended period. The design has been a significant participant in this transformation since it can anticipate requirements and trends, imagine probable outcomes and, eventually, synthesise a feasible solution. Designers are born to initiate communication with all of the actors and play pivotal roles. Since the 1970s, efforts to incorporate future users and other stakeholders into the design process have resulted in the development of various methodologies dubbed co-creation or co-design [

10]. Today, these ideas may be practiced and thought about in many ways. While we will not go into detail about them here, we should note that we concur with Sanders and Stappers [

10], who define co-creation as an act of collective creativity, i.e., creativity shared by two or more people, and co-design as the creativity of designers and non-designers working collaboratively on design development [

11]. Design prototypes are not only progressing objects or objects-to-be; they also have a much broader social relevance, projecting into the public sphere a set of ideas, methods and procedures that connect practical issues to abstract issues, thereby assisting in the creation, shaping and management of social links [

12]. They take in various forms and are critical for disseminating ideas [

13]. Sanders and Westerlund [

14] proposed the notion of co-design space, which may be thought of as a prototype for facilitating and improving creative participation from stakeholders who may not consider themselves designers. Additionally, they observe various issues when design professionals and non-experts collaborate. These include devoting an excessive effort to a single early concept rather than investigating several other options and engaging non-experts in ideation when their knowledge of the topic is insufficient.

Similarly, some co-design participants may believe they are not the ‘creative type’. Sanders and Westerlund [

14] argue that these issues can be mitigated significantly by the environment in which co-design processes and techniques occur, as it can act as scaffolding for participants’ creative expression and contribution [

11].

Sanders and Stappers [

10] attempt to connect co-design to a long history of participatory practices by presenting it as the result of the convergence of two distinct approaches: user-centered design, which originated in the American tradition and viewed the user as a subject, and participatory design, which originated in Scandinavian countries that look the user as a ‘partner’. Manzini and Rizzo [

15] allude to bottom-up efforts in which a varied group of actors unite to envision and affect social change, similar to the first chapter of their book, which discussed creative communities, and engaged citizens. These are positive examples of bottom-up social innovation that, according to the authors, may be regarded as a kind of participatory design, or more precisely, a participatory design project in which social innovation is both the result and primary driver [

2]. Along the same lines, Bannon and Ehn [

16] agree that participatory design has significant potential to contribute to social innovation initiatives, but this also implies several distinct challenges: introducing design practices into environments where no object is being designed, where local actors with divergent agendas and resources interact, and where the designer is just one of many professional actors who contribute to pro bono work. The public-interest services relate to design for services in its more systemic and transformative conception, and furthermore, they relate especially to the ‘functional’ paradigm, offering access to essential ‘functions’ of everyday life by developing ‘solutions’ for a social collective construed as a ‘public’ [

2].

The fundamental values of society and the relationship between public institutions and citizens must be recovered in the contemporary age. This idea recaptures values mentioned before from Roman and Greek cities, where governmental institutions had a different value from the general public’s perspective. This is a challenge in the contemporary city because of the complexities found nowadays, the requirements of cities, the fast shift of technology and the constant reinvention of services.

Kjetil Thorsen [

17] says that “in the layered systems of our cities of the future, we will need to focus on the public spaces that are found inside buildings—and make them accessible”. The public interior of institutions should be understood as a prolongation of the outer public space. The activities inside are different but can open new ways to create social encounters and unexpected activities that add to those in the outer public spaces.

The relationship between the public and private spaces inside results in a line of separation that has begun to be diluted. The role of design to create a public interior space has its first steps in primarily understanding the role of the waiting room in the new era and proposing a step forward into adding innovation in the behaviors of waiting in the digital world. The digital change in the way services are provided within governmental institutions is currently changing and the spaces are still searching for solutions that can respond to those adjustments.

Digitality and physicality are concepts that have been recently explored in order to understand the new, challenging demands inside space, social media and technological tools, as they have changed the way in which people relate with the world today. Nowadays, the existence of a digital space cannot be denied, citizens’ behaviors are dependent on the digital world, which has changed the way people are connected between physical and digital space; the access to this second space has become a representation of the new digital era.

Technology and innovation have created a singular, new way in which the world relates, and how institutions must approach users and future generations, shifting the way services are provided. The challenge is to understand how to idealise stronger and new relationships and break the idea of hierarchy, providing a commonwealth that is achieved by understanding the role of each organisation. Even though the first approach towards understanding these concepts is explored in the third spaces [

18], others have explored the role of the virtual–physical continuum that blends both environments together. Those blended spaces act as mobilisers and socialisers at the same time, whereas space is a platform to either attract people to connect to the digital environment or to to socialise physically in the same space.

Italy has the “Three-Year Plan” for 2020 to lead its public administration to digital transformation. The development of a digital signature (SPID) has become an example of how businesses and citizens identify with the public administration, but there is still a lot more work to be conducted. The goal of eGovernment should be to have greater simplicity in services, and speed and transparency in the management of public services, in order to provide a more inclusive and modern technological procedure [

19].

Services are becoming ever more effective, accessible, and timely as the digital world changes the way they are delivered (not for all the segments of the population), which are characteristics users are searching for. It is not a mystery that each time a physical presence is not required, digital services are making it less necessary, and at an ever-increasing pace. The Chamber of Commerce, in fact, is gradually shifting its services to the online sphere, thus decreasing the need for a tangible presence for many of its services. The digital systems still require time for adaptation; there are still many doubts about security and a lack of confidence within the whole system about becoming a completely digital world. People still value the physical, and in order to become digital, a generational shift, time, adaptation and evolution are required. Services will adapt to new requirements once the transition is made. Becoming digital is not a thing of the future, it is currently being undertaken by many Chambers of Commerce throughout the world. The concept of digitisation as a speedier method of communication, with no waiting lines, rapid service and immediate payment, among other benefits, is a component of the new digital era for the public sector that is being adopted in a number of nations within the EU [

19]. At the same time as there is a great deal of discussion on these issues, involving different opinions and continuous evolutions, the space as a container for these services is less subject to reflection and not considered for any evolution in design. What are the main characteristics of spatial heritage in terms of the public sector, when these digital services are an integral and generating part of an openness with the city and its citizens?

3. Restoring Space Heritage for Public Administrations

Public institutions are regulated and funded by the government, and they act as the government’s presence in different areas and activities. Since the foundation of the Greek cities, the agora was a spatial political expression of the ideal lifestyle. The agora represented the place of gathering and it was where all the political and religious institutions were located, conforming to the physical representation of the city, which was founded with a logical organisation and distribution. In the same way, in the Roman cities, people gathered in the public square for public institutions, religious rituals, the justice system and business—which differed from the Greek ideal—and it was located together with the public forum in the center of the city. There was an open space for the community to share their thoughts and participate in the creation and development of their community. Romans and Greeks shared a common interest in how political ideas were shared with the public, and the buildings served as a public space, an ideal that has been losing importance over time, especially in modern and postmodern cities [

20].

The foundation of civilisation is based on this concept, open spaces for encounters to develop ideas and society itself, whether from a political, social or economic perspective. Public interior space in modern cities has been lost, as the new spatial requirements have become more complex, with the role of public institutions being rather limited to governmental functions, reflected in functional buildings and their interiors.

Nowadays, the sizes of growing cities have transformed their relationships with public space. There is a scarcity of public areas that are able to respond to all the current requirements. There are new ways of communication, socialisation and interaction. The future must re-evaluate the public interior to create a new network of relationships for the city and the urban life of the citizens.

The latest digital dimension has created new service opportunities, such as the integration of coffee shops, shopping malls and other sorts of locations, which have enabled the visualisation of new public domain forms. Physical touchpoints must attempt to attract or provide opportunities for new activities; sociologist Ray Oldenburg refers to these spaces as third places (first places are defined as homes and second places are defined as workspaces) [

18].

Since cities’ inception, public institutions have played a critical role, traditionally serving as a symbol of local power and authority. Nowadays, the image perceived by citizens (at least in Italy) has changed towards one of cities becoming less engaged with the public and instead focused on creating a deeper bond with the government rather than general users. The public sector must produce public goods, and, through the creation of new missions, it catalyzes investments from the private sector. These new missions should tackle the most pressing social issues of climate change, ageing, inequality and youth employment [

2].

Starting with the Italian Government Definition: “Public buildings are those that belong to public bodies and are intended for public purposes”. For example, ministries, military stations, schools, hospitals, churches, markets, universities etc. are public buildings. They cannot, however, be defined as “public” buildings constructed by the State or other public bodies acting “jure privatorum” as this would represent the exercise of activities of a private nature. Buildings of public interest are considered to be those which, although not constructed by public bodies, have a clear and direct public interest. To this category belong, for example, the buildings constructed for the headquarters of public law bodies: museums, libraries, etc.

In the UK, a narrower definition of Public Buildings is adopted, namely a building that is “occupied by a public authority and frequently visited by the public”, and “frequently visited by the public” is defined as “daily attendance during days of operation by people for purposes unrelated to their residence, employment, education or training.”

This means, for example, that a school used only as a school is not a public building because it is not attended daily by people who are neither staff nor pupils. However, a school that is also used daily for community functions is a public building.

Since their origin, public institutions have played a critical role in cities, traditionally serving as a symbol of municipal authority and power. People’s perceptions of public institutions have shifted in recent years: citizens may feel alienated from or less involved with their institutions. Cities that are the most progressive are those in which public institutions offer forums for civil discourse. As a result, public spaces are critical, as they are the sites of “civility” (Evers, 2010) [

20]. Evers views “civics” as a mutually reinforcing concept with “civility”, defining it as people’s identification and function as citizens, the influence and quality of citizens’ collective acts, and the role of public institutions in nurturing such behaviors by providing a place for them.

“It’s not the first time that architecture attempts to go beyond architecture, but in the twenty-first century this utopia seems to be for the most part realized within the contemporary city, where the environmental evolutionary processes and immaterial reality of computer networks have already created a defacto, dynamic, invisible, and abstract metropolis that is progressively substituting (or moving to the background) the physical and figurative metropolis”.

As new commercial and industrial institutions arose in Europe during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the creation of new businesses institutions, such as those dedicated to public administration, jurisdiction, education, discipline and consumption, proved the concept of “interiors” as the representation of a new kind of public sphere. The concept of “accessibility”, which is defined as the ability to visit an area without doubt or difficulty, serves to further illustrate the gap between Public Spaces and Public Interiors (Poot et al., 2015). As a result of practical constraints, the “permeability” to a Public Interior may be limited in terms of time duration [

22].

The creation of the surroundings of such interiors for the purpose of public performances supplied the city with a succession of locations for a variety of collaborative endeavors to take place. Subsequently, as technology advanced and the physical logistics of enhanced control became more sophisticated, public and collaborative behaviors were more housed inside structures. This “interiorization of public life” (Çiçek et al., 2018) [

23] shows how some areas of the city are in continuous relationships with certain interiors, or as Koolhaas (2002) [

24] refers to them, as “infrastructures of seamlessness”, where the boundaries are no longer clearly defined.

The main interest of public services is the well-being of a group of citizens. This group usually shares a common vision of an ideal world and the changes required to achieve it. This kind of service takes part in a local context due to its impact being on a smaller scale [

2]. As the well-being of a social group with shared interests is intended to be the motor for the existence of many public services, institutions must change towards user-centered models. These models shift the importance of the institution towards the users as it opens up the space for them to participate in the creation of the ideal. Institutions will be enriched by the experience of recovering a closer relationship with its users, and also among them while they inhabit the space.

Meaningful encounters in the physical space are produced either by the conditions of space or by the type of users that are attracted to it [

2]. This engagement requires different approaches: in the first, the space is a protagonist to allow social encounters, while the second approach allows social encounters due to a common activity and shared interest between users. The benefits of enabling those situations create a common space both for the institutions and citizens, a threshold between the public and private interiors that impacts the public spaces of the city as political motors.

The Chamber of Commerce is defined in the Cambridge Dictionary as “an organization of businesspeople who work together to improve business in their city or local area”. The first and most important element is the community component; it is the basis of its existence, the idea of a group of citizens united by a common theme. The second most important element refers to the territory, its roots established in a specific place, where the common goal is to improve economic transactions and development of a territory. In this sense, the community is rooted; this creates a proud community that wants to grow, in which the members want to help each other to reach a common goal, and along the way, some other activities of encounter, learning or work occur. One of the main interests of the Chamber of Commerce is the creation of new companies and businesses to expand the market and the local economy: it can provide tools and support to new members to understand the best strategies and benefits of registration that best fit the business idea. The strengthening of existing businesses is focused on keeping partners and helping them grow, moving to new trends and adapting to new and evolving systems. This idea of having an “open government” dynamises the way in which the system interacts with the citizens in order to co-create innovative solutions. This method offers inclusion and collaboration to introduce experts and non-experts to a new process within public administration [

25].

4. Hall of the Future Project

The project described in this article, the Hall of the Future project, is based on a collaboration between the Chamber of Commerce, Industry, Handicrafts and Agriculture of Monza, Milano and Lodi and a team of researchers from the Department of Design of the School of Design at the Politecnico di Milano. Its aims were to upgrade the Chamber’s Salone Anagrafico with a future vision for the digitisation of services provided to citizens and achieve its spatial redistribution. It is interesting to note that there has already been a collaboration between the two bodies, for the realisation of a project called Tourism Space for the city of Milan, with the support of YesMilano.

The YesMilano Tourism Space, located in the historic Camera dei Notari, inside Palazzo Giureconsulti in the heart of Milan, welcomes tourists and citizens into an environment where analogue and digital technology meet, creating a multi-sensory experience in an informative, engaging and unexpected space to discover Milan and Lombardy. Two touch-screen mirrors lead to the discovery of a hotbed of ideas for visitors to the city. A large interactive monitor that resembles a hanging picture welcomes the visitor with colorful, changing patterns. In the evening, this closed space comes to life as a real multimedia magic lantern; the projections on the inner walls of Camera dei Notari change with just a touch on the glass window.

It becomes a welcoming environment to take a break from city traffic, recharge one’s batteries and live an immersive experience: interactive maps, multimedia screens and night projections guide the visitor to the discovery of the city from a new point of view. The new digital space in the heart of Milan is ready to welcome and astound tourists, and more and more time is spent collecting useful information to outline an experience of the city itself; with increasing frequency, we are becoming accustomed to using personal devices to move in new contexts and orient ourselves; after long journeys, we feel the need to release the tiredness of the body.

The Chamber of Commerce and the Politecnico di Milano, thanks to a selected research group including designers with different disciplinary backgrounds, have established a collaborative relationship in the sphere of design study, specializing in the supply of novel services to the worlds of tourism, business and commerce, as well as the subsequent functionalisation and enhancement of their environments.

The building that today is occupied by the Chamber of Commerce of Milano, Monza and Lodi is located at a strategic point in the center of the city. The Palazzo Turati is a complex bordered to the north by Via Meravigli and the iconic Piazza degli Affari and on the south by Via San Vittorio al Teatro. The project proposal developed the necessity for the Chamber of Commerce to redesign its Salone Anagrafico (

Figure 1), an iconic location, resulting in the creation of a modern space capable of supporting and fostering interaction and discussion between institutions and citizens, as well as between institutions and the surrounding community. This interior represents an important and strategic step for the Chamber of Commerce but also, more generally, for the commercial and entrepreneurial fabric of the Lombardy region and of its national territory.

Aiming to make its relationship with users more accessible and more effective by gradually digitizing its service offerings, the Chamber of Commerce hopes to achieve significant benefits in terms of cost reduction, process optimisation and simplification, an improved overall relationship with its customers, and quality of services.

In recent years, in the spaces of the Salone Anagrafico, the activities of assistance and accompaniment have been expanded to include the use of digital tools and many innovative services. Therefore, the need for a place where the user can feel welcome and interact with the operator, and possibly work together on a PC, tablet or smartphone, was created. The workstations, being essentially composed of a desk, high-performance PC and armchair, meet the need for maximum flexibility, but at the same time must be able to guarantee the privacy of the user. The digital assistance to the services could also be carried out online to reach companies at their headquarters.

Today’s architectural distribution shows a misunderstanding of the original building, providing a functional solution rather than a holistic proposal. The spaces that are created as a result do not establish a good relationship with the original space. In fact, the interior space has not taken advantage of the natural light coming from the main facades and the central area. The central ceiling uses light to hide technical solutions for the air conditioning system, creating a dark space that gives the feeling of a timeless space.

The richness of a space is important in interior space, and the themes of light and ventilation must be addressed in the best possible way to create a space that is comfortable. Workspaces and waiting areas must have the best conditions to create a pleasant space for each activity.

In the diagram above (

Figure 2), you can see how most of the building does not receive natural light; only the facade provides light and the internal divisions block this out. This situation creates a dark central space that only receives indirect light from the ceiling and does not use it properly. The end result is the feeling of a timeless space, which feels dark and disconnected from the outside.

The actual space is presented without levels of gradual separation of the services and space used for the public (

Figure 3). The Chamber of Commerce requires a clear separation of its program in terms of space from the point of view of accessibility to public and private offices: a possibility to become an extension of the public domain through strategies such as opening up spaces, creating more than one access point or utilizing materials related to public spaces and localisation.

The main objective of the Hall of the Future project is to define possible scenarios for the future experience of citizens within the Salone Anagrafico, developing the most promising solution in terms of a feasibility study. Specifically, the project is divided into five phases:

Preliminary investigation of all available materials and preparation of the project research activity, appointing scientific coordinators and project managers for the different activities.

Field research, conducted through interviews with current users, ethnographic observations and co-design activities; intensive concept generation sessions and the development of some components of the design solution, in terms of services and user experience, deepening some “touchpoints” between the Chamber of Commerce and citizens.

Systematisation of the first results and identification of the most promising project guidelines, in order to identify a shared structured brief.

Elaboration of the project proposal chosen at the feasibility study level. The fourth phase deals with the services provided and, more generally, the overall experience of the user, within the space of the Hall of the Future project. A careful analysis of the installation dimension of the space, of the furnishings, of the lighting system, of the environmental graphics and of the technologies supporting the dialogue between the Chamber of Commerce and the citizens will be started.

Artistic supervision of the realisation and monitoring: support in the choice of the suppliers and in the form of co-design until the beginning of the implementation of the suggested project.

In the first phase of the project, students from the three-year degree in Interior Design and Product Design took part in an interdisciplinary workshop, with the aim of analyzing the current state of the exhibition and formulating some initial working hypotheses from the point of view of Interior Design and Product Design, with particular attention being paid to the design of furniture and interaction, given the quality of space and its architectural artifacts. Specifically, the contents and needs of the Salone Anagrafico were analyzed, international case studies were selected, and design concepts were subsequently generated through field research and interviews with current users of the space.

Again, the students participated in parallel after the delivery of the feasibility study of the research group’s project (phases 4 and 5), through the lessons of the Product Service System Design (PSSD) course in June and May 2019. During the course, the students focused on reorganizing the internal services of the Chamber of Commerce that are active in the Salone Anagrafico, and also on adding new services.

The research group gathered for the Hall of the Future project, including actors from different disciplinary backgrounds: interior designers, graphic designers, service designers, lighting designers and architects. The research group supervised the various phases since the beginning of the collaboration, focusing their work on a feasibility study for the realisation of the project.

In the first two phases, the design focus was on the analysis of the needs and requirements of the client, drawing up the first ideas in terms of space, service and user experience. In the third phase, the first results of the interdisciplinary workshop and field research were systematised in order to be able to identify, together with the client in private meetings, the most promising design guidelines. A fundamental part of the design system was the meeting between the Politecnico di Milano and the internal actors of the Chamber of Commerce of Milan to support a co-design session for the design of spaces according to the services provided.

The project’s design had to be defined by three key parameters, according to the demands of the Chamber of Commerce:

Flexibility: The new workstations and display spaces needed to be able to adapt dynamically to the provision of additional services and activities. It was necessary that the spaces and the supplies would be able to offer services in the future that could not be imagined or foreseen at the time of the project’s design.

Continuity: The Chamber of Commerce needed to remain a point of reference for services geared toward company success and the economic development of the territory. The offer of services in the Hall of the Future would, therefore, be renewed and expanded, but starting from what was present. Internally, especially in the initial start-up phase, the importance of ensuring a sense of continuity and a way of working that was not completely different from before, in order to gradually integrate the innovation, was understood.

Innovation: The new salon needed to have a modern look and offer different types of services, spaces and cutting-edge possibilities. It was also required to convey a sense of welcome and ‘care’ towards users, which could be achieved through a dedicated design and the use of greenery.

In the next section, the main modalities of co-design, the main focus of the methodology applied in the project, will be explained. The latter two stages focus on the services supplied and, more broadly, on the entire user experience inside the Hall of the Future project’s area. The feasibility study includes an in-depth examination of the chosen project concept, an examination of the project itself, an indication of the hardware and software supplies anticipated, an examination of the technical and technological requirements and an examination of the intervention’s economic impact. Following the completion of the renovations, a period of monitoring the space’s usage was decided upon.

5. From Co-Design Session to Project Feasibility

“As public services face substantial challenges with demographic, social and environmental trends, along with the challenging economic times, it has never been more important to work together to design and improve public services for all. We argue that design can help address the complexity of such challenges through harnessing collaborative approaches to public service innovation and improvement. By doing so, we can not only design better services, but also develop lasting skills and capacity within service providers and users”.

The article describes the Hall of the Future project, which is the result of teamwork. Co-design in public-interest services and venues is critical from a strategic standpoint since it pertains to the formation of a ‘public’ around a particular problem and, most importantly, the process of co-design should magnify individual interest into a public interest [

2]. The term “co-production” refers to the idea of collaborative services [

27] and the Cottam and Leadbeater co-creation model [

26], which entails the inclusion of users at every step of the solution’s development and the use of a set of virtual and physical resources associated with a particular context. Because public-interest services are concerned with the long-term survival and well-being of a social collective, process and results should be co-designed and co-produced by users and citizens [

2].

Sanders and Simons [

28] highlight diversity as their second prerequisite for co-creation with implications for social transformation. They state that if the participant group consists of people with similar backgrounds and perspectives, the outcome may be predictable and limited. Several other researchers share their view [

29]. One could argue that most of the suggested reasons to apply participatory methods—such as the variety of ideas and skill sets, and empowering people through engaging them—promote the inclusion of a heterogeneous group of stakeholders. The value of diversity is yet another reason why the design processes should not be carried out solely by a group of designers, especially when it comes to the co-design processes with social impact, in which the success of the process depends largely on the commitment of the greater number of people [

30].

As already described in the previous paragraph, the most important activity for this project was the co-design between the internal bodies of the Chamber of Commerce of Milano, Monza and Lodi and the Politecnico di Milano team, concerning the spatial layout and the definition of internal services for citizens. The three design features requested by the client were considered: flexibility, continuity and innovation. These three aspects were grouped together and summarised in the concept of ‘open’, a leading design thread to respond to design needs. With the concept of ‘open’, all spatial and service elements were considered, as if they were to embrace the public and express security and flexibility in terms of experience. The value of open space within buildings is a strategy used in most existing international projects to relate the different interior spaces, which converge towards the central space, providing the feeling of a healthy environment (light, ventilation and temperature control). This type of space tries to merge most public and semi-public areas into a single experience that is open to the visitor. The interior space corresponds to a threshold space between the public road and the private offices within the building: a connection with the city through a complete and direct accessibility to meeting and waiting spaces for the public. At the same time, it provides an opening to the existing and new functions and services that are carried out daily within the Salone Anagrafico, replacing the barriers between officials and the public and opening up towards the digitisation of the same consolidated services in addition to the new ones introduced in recent years. Following the various required characteristics, the many spatial and interaction problems, and a contemporary look at the design inputs, the co-design session was very useful in finding answers and creating a totally participatory project with the Chamber of Commerce of Milano, Monza and Lodi.

During meetings between the two organisations, co-design sessions were held in which a variety of actors with a variety of working abilities participated: designers, architects, managers, government officials, members of the press and service administrators. The primary goal of the co-design process was to establish a spatial arrangement that met the needs of the client while adhering to their constraints and requirements, and that was appropriate for the services offered for the Hall of the Future project’s function.

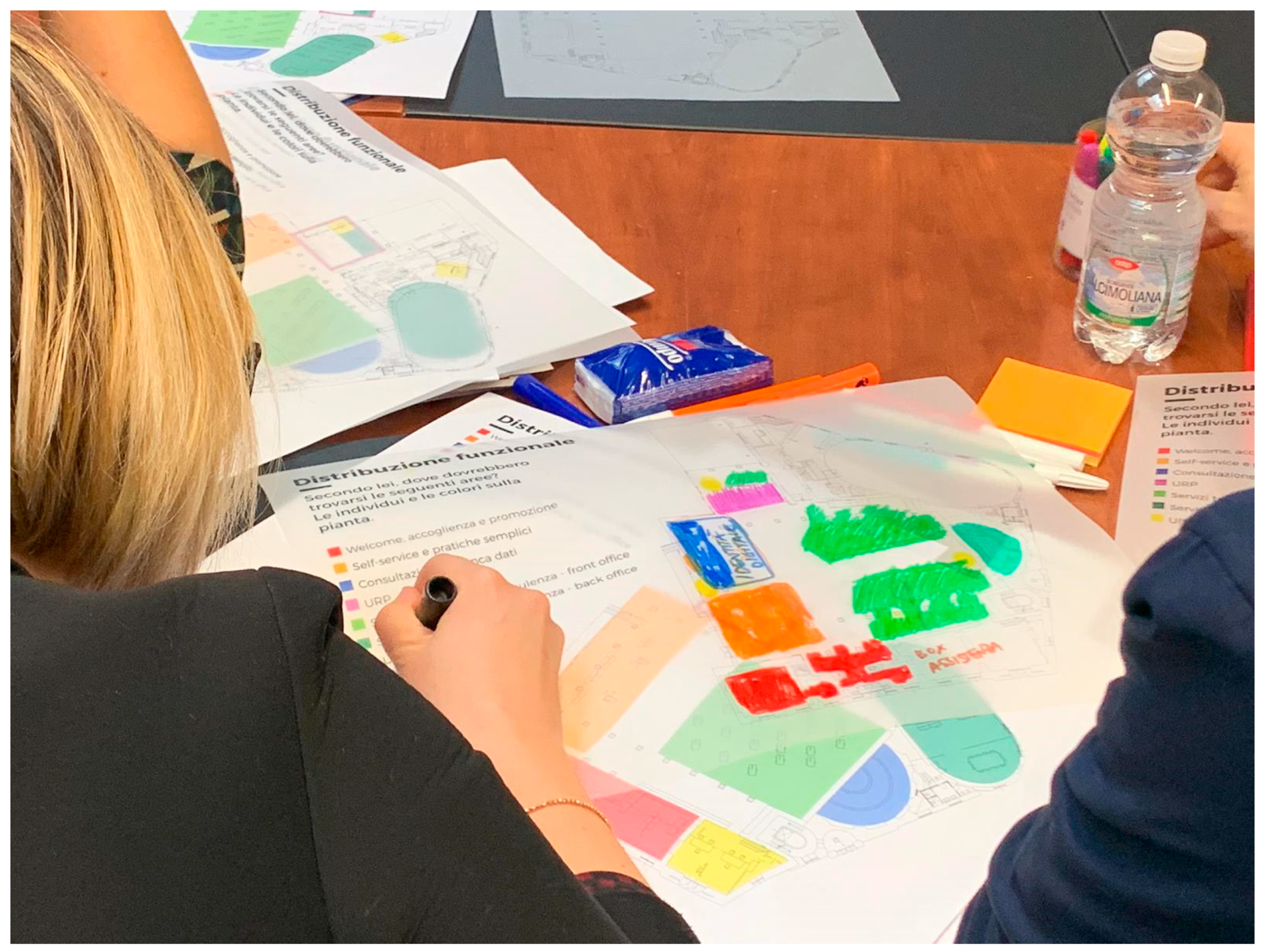

After a brief introduction with the various indications for the co-design session, each of the participants was given a map of the Chamber of Commerce designed by the team of researchers from the Politecnico, with no reference to furniture or other elements, but with details of access, architectural limits and a first layout decided by the researcher team. This printed plan was the first tool used during the co-design session as a sort of spatial guide to indicate a first preference for layout, a guideline of the activity but not a definitive one (

Figure 4). In fact, the second tool used consisted of a semi-transparent graphic board, to be placed on the first sheet, and according to the present legend, participants expressed their spatial distribution preferences, modifying the one below if it was different. The legend was composed of a series of colors, each of which denoted a certain space/function. After receiving both graphic supports, the activity began individually, followed by a group discussion to choose which spatial division was the most fascinating and appropriate for the project. Following that, each participant received a dossier, which served as a third tool for monitoring the co-design activity in terms of the furniture and spatial component selection for each region of the plan. Each dossier was separated into three categories based on its space/function: furniture, textures and colors, and digital and technical assistance (

Figure 5).

By acting together and examining each individual region, each participant expressed his or her choice by selecting from among those offered or, in certain situations, by contributing external recommendations. Additionally, the dossier considered various modes of usage and interfaces in terms of service and support.

Before the end of the meeting, a collective recap of the activity was made, and a summary of the choices, in terms of spatial layout, was produced, with suggestions related to furnishing accessories, atmosphere and services given from the point of view of the interface with external users. These final elements were fundamental for the realisation of the feasibility study for the Hall of the Future project and to proceed with the drafting of a project that would respond to the initial requests of the client in terms of the redistribution of the internal space and support related to services and experience (

Figure 6).

Following this co-creation activity, a careful analysis will be started of the exhibition dimension of the space, of the furnishings, of the lighting system, of the environmental graphics and of the technologies supporting the dialogue between the Chamber of Commerce and the citizens. This phase will end with the delivery of the entire feasibility project and, in addition, useful indications for the future drafting of specifications for suppliers of finishes, fittings, furnishings (

Figure 7) and graphics, quantification of the maximum technical and technological requirements and economic quantification of the maximum intervention.

6. Conclusions

The actions undertaken by Chambers of Commerce must be immediately changed, since technology is shifting at a pace that was not previously imagined. It seems that traditional systems are resistant to this switch, and as a result, the opportunity for transition is slowly becoming a necessity. Using technology to amplify the capacity of workers in their jobs is one of the biggest changes. When utilizing human capacities to improve technology—as machines follow a series of commands—it is important to have the correct inputs and interpretations to take advantage of future technological offers.

The Chamber of Commerce applied the values of transparency, effectiveness, economy and efficiency to this design project, encouraging the participation of users and the pursuit of quality in its services. This approach also encourages a progressive digitalisation of services offered in the hope of enabling and enhancing connection with customers, which also allows cost reduction, quality management and simplification, and an improvement in the quality of services provided.

The significance of this paper lies in its further explication of the role of co-design and participatory design in public services through the use of tools, related to space and spatial layout, and the assessment of their contribution to service improvements and new solutions. It is important for public service organisations, service users, policymakers and other stakeholders to understand the contributions of design researchers, as this will inform about their practices and capacities and how best their competencies can be channeled towards enabling economic development.

Working closely with the end users, namely the Chamber of Commerce’s managers, during the co-design process was not easy. Indeed, each user stated distinct needs, which were frequently incompatible and could not be met concurrently. Some shown a greater willingness to adapt to change and advancement, while others rejected this. A fascinating feature that arose and sparked the use of co-design tools is that many users stated a desire to change during the initial interviews, but were hesitant to adopt the initial recommendations after viewing them. As a result, the Politecnico di Milano team recognised the importance of establishing shared stakeholder conceptions and developing tools that would enable non-designers to participate in the project’s debate. According to Stappers and Sanders (2008), there are at least four distinct types of creativity: doing, adapting, making and creating. [

10] As a result, it is critical to understand “how to provide meaningful experiences that enable people’s creative expressions on all levels” (Stappers et al., 2008) [

10]. The proposed co-design tools were found to be engaging, as the Chamber of Commerce team began implementing comparable co-design tools (namely, spatial layouts) in order to visually express and debate their ideas in an autonomous manner, as a fresh method of analysis and design.

The co-design technique allows for a shift in the conventional duties of the designer-researcher, from translator to facilitator. In this instance, the design team also served as a mediator, able to broker agreements between the various players.

Finally, this type of proposal, which includes governments, citizens (users), and research and education institutions (universities), can serve as an example for future research studies focusing on the growth and improvement of territory and public spaces, as well as for other types of initiatives (Collina et al., 2020) [

31].

The Hall of the Future project is taken as an example of the importance and the need to support research activities in co-design sessions, creating tools that can proceed in the right direction for the packaging of a project. This system of co-design, along with the methods used, may serve as a reference framework for any project involving spaces, and, in particular, public interiors. It has the potential to be enhanced, and, in particular, developed in accordance with the needs of the customer to whom it belongs.