Analysis of the Awareness and Access of Eye Healthcare in Underserved Populations

Abstract

1. Introduction

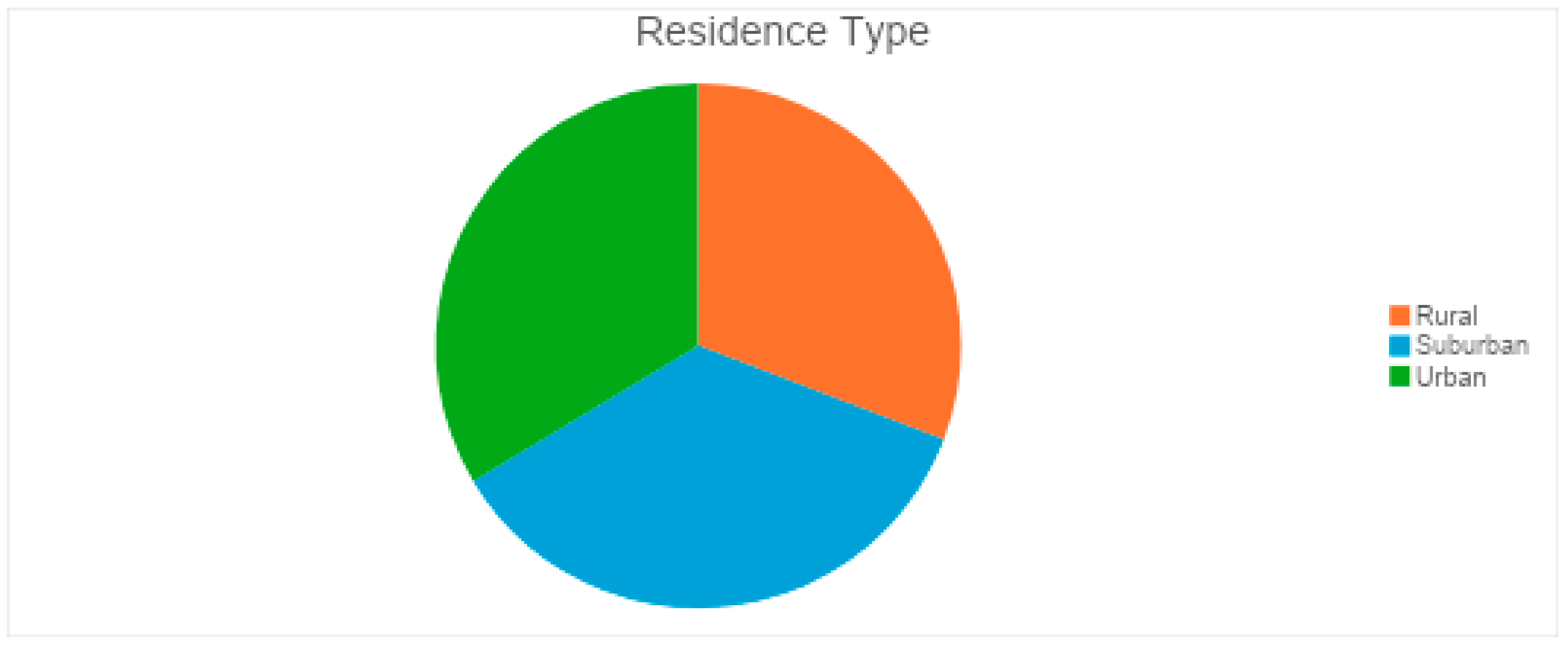

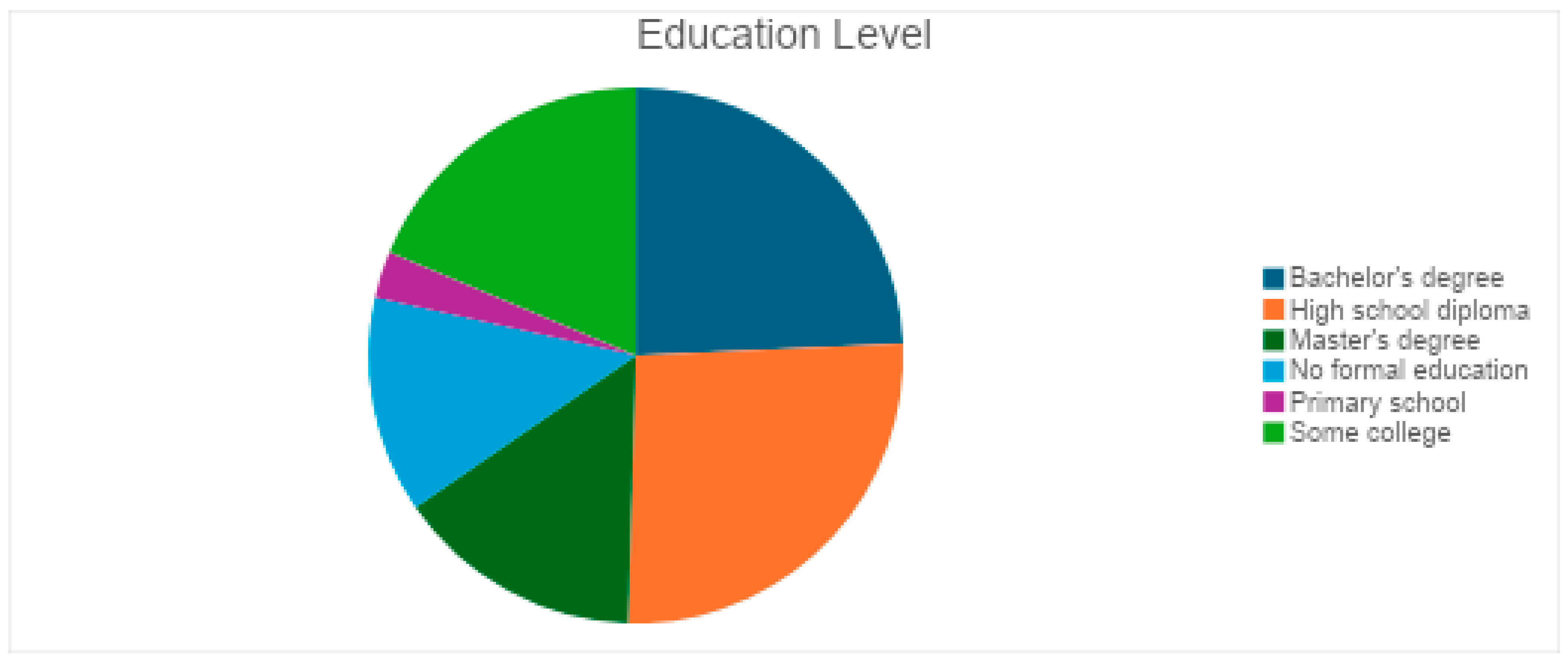

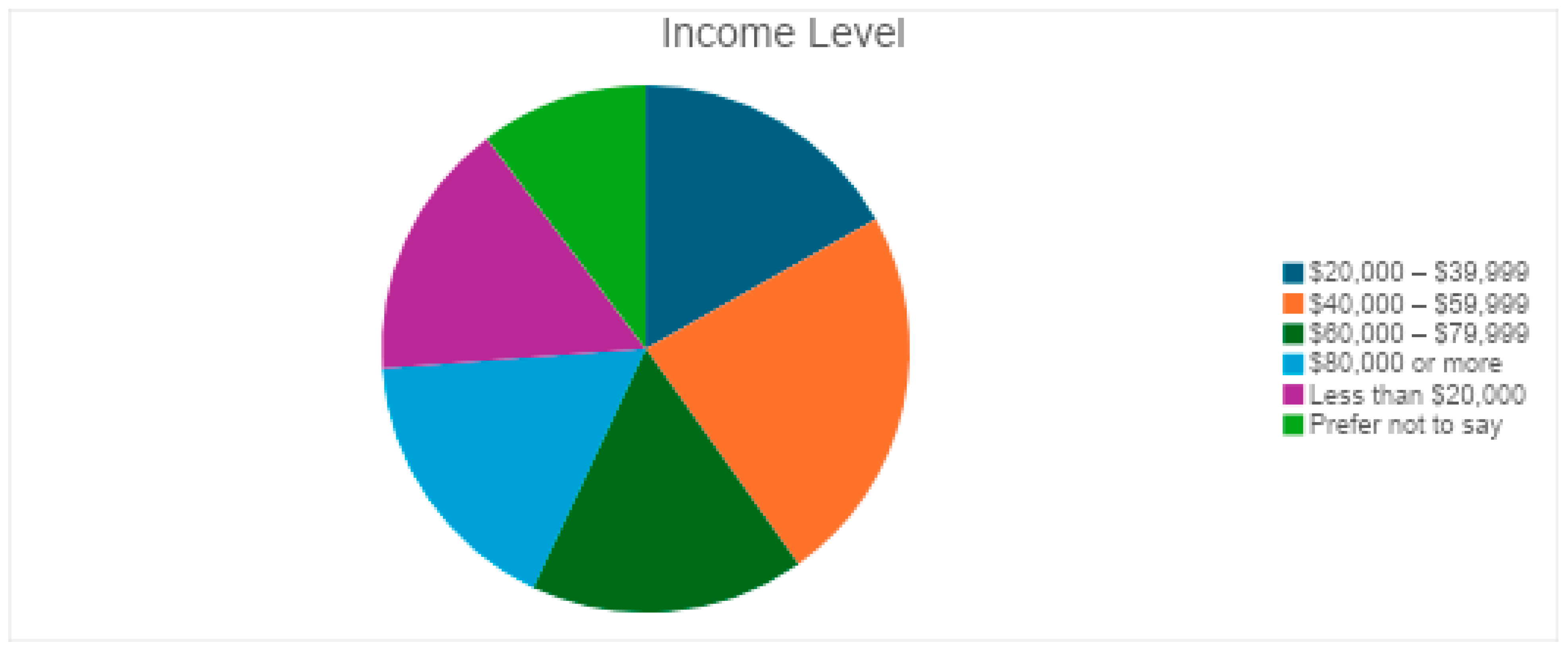

2. Methods

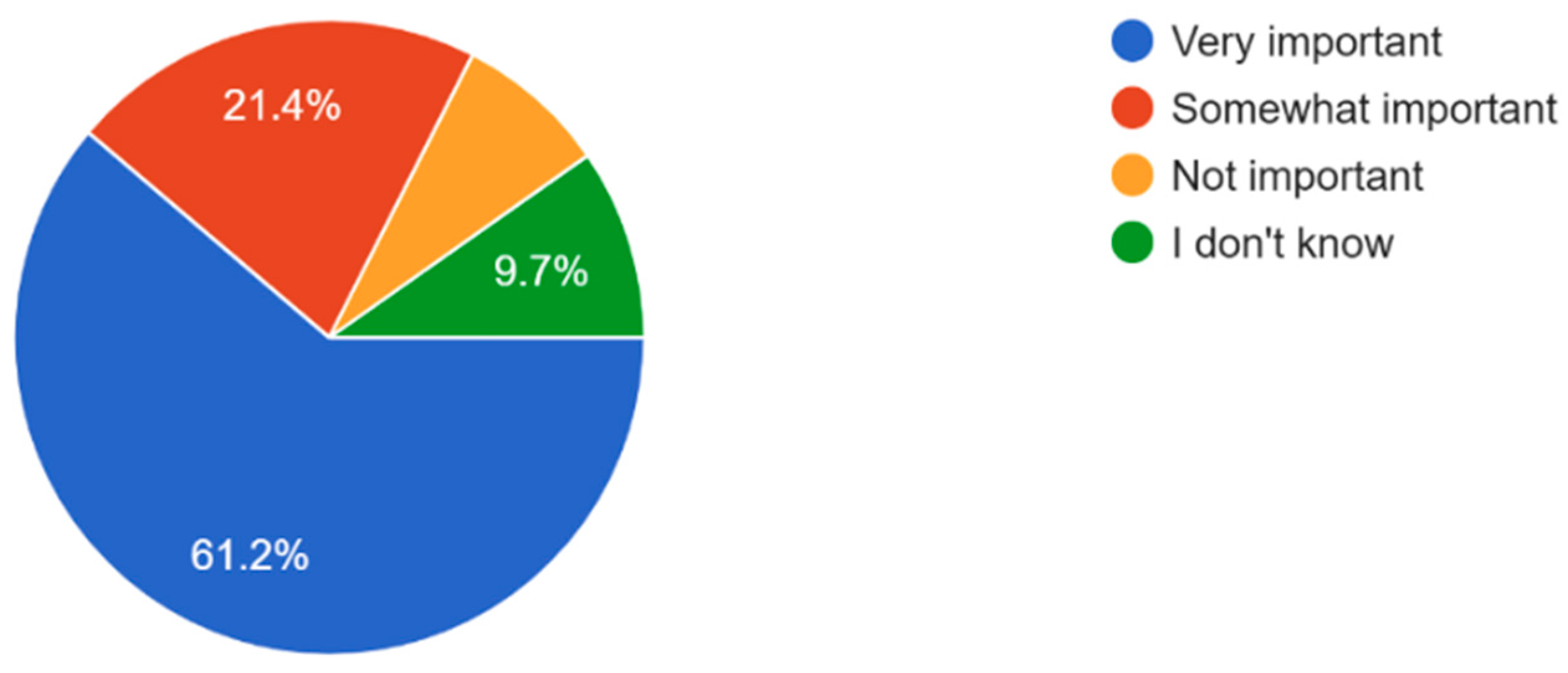

3. Results

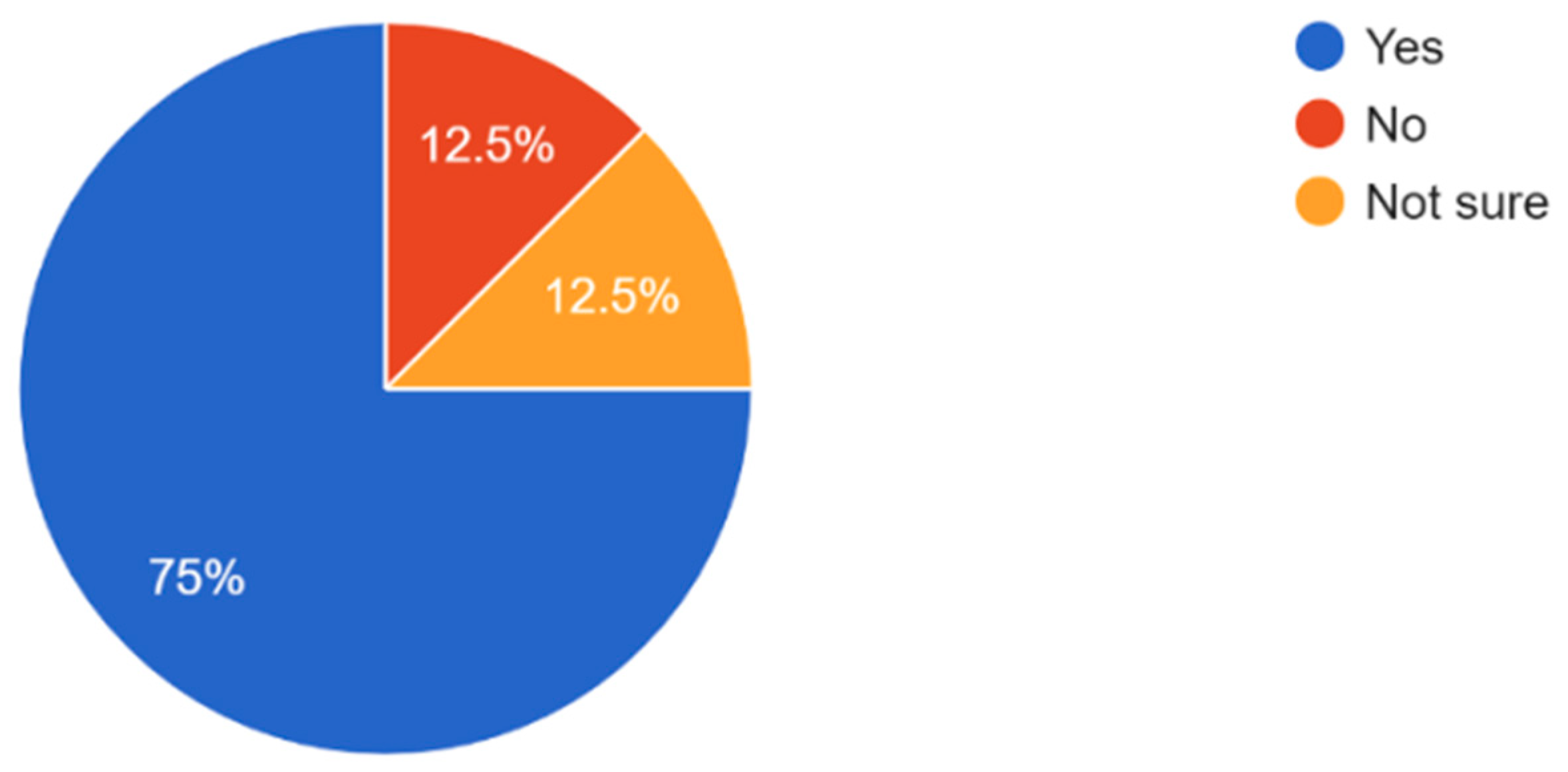

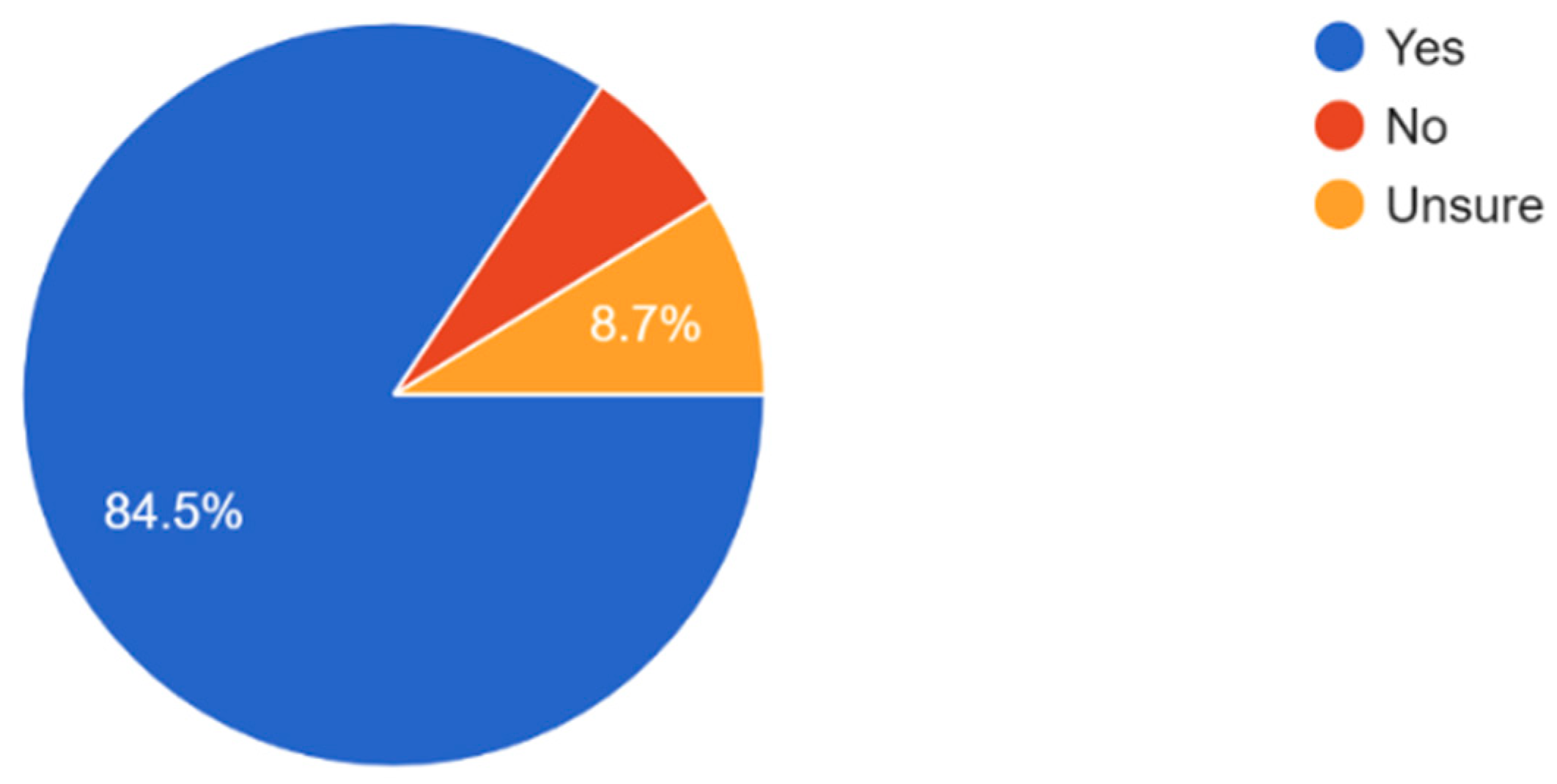

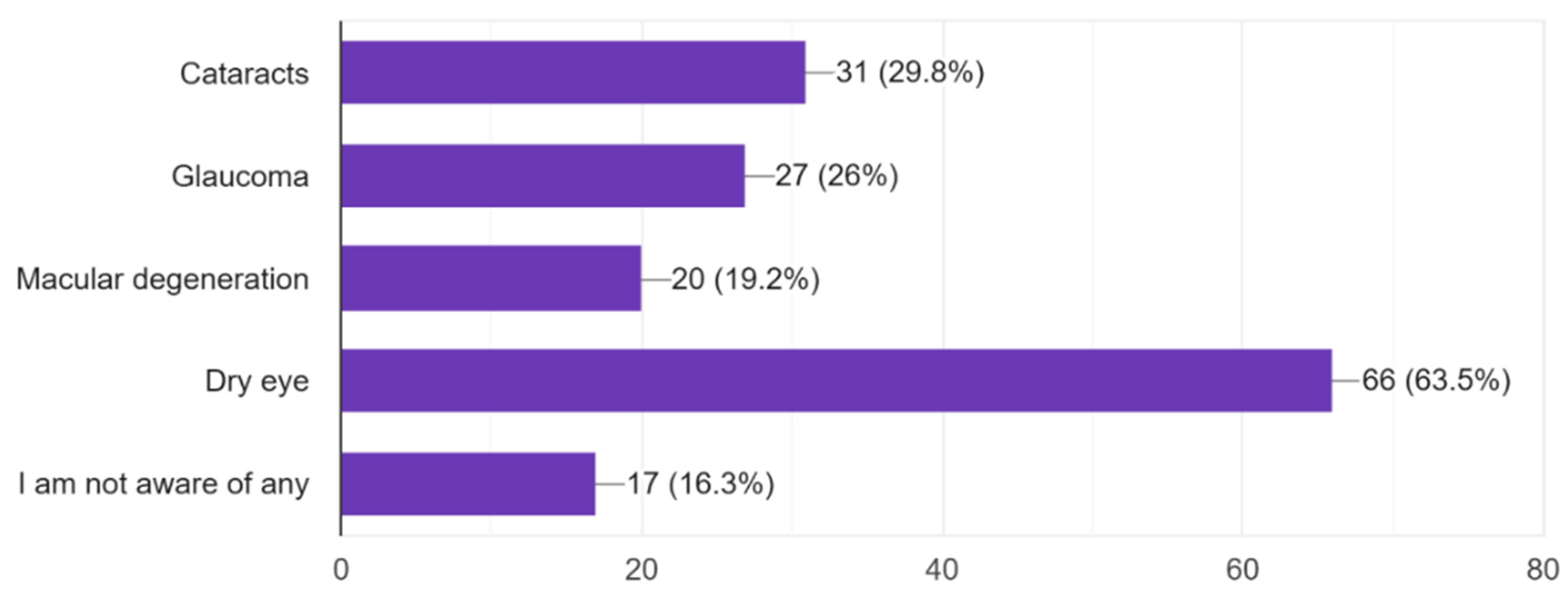

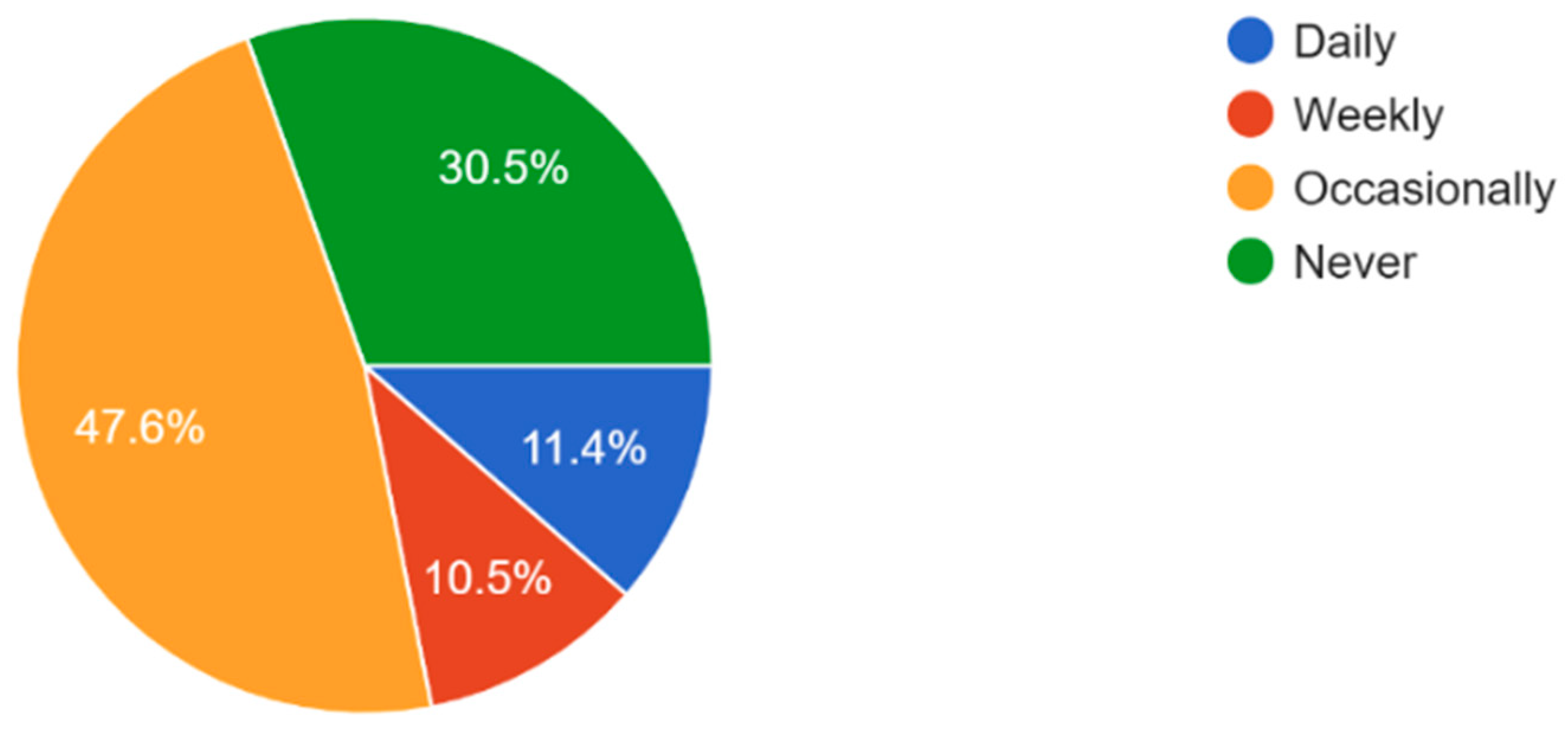

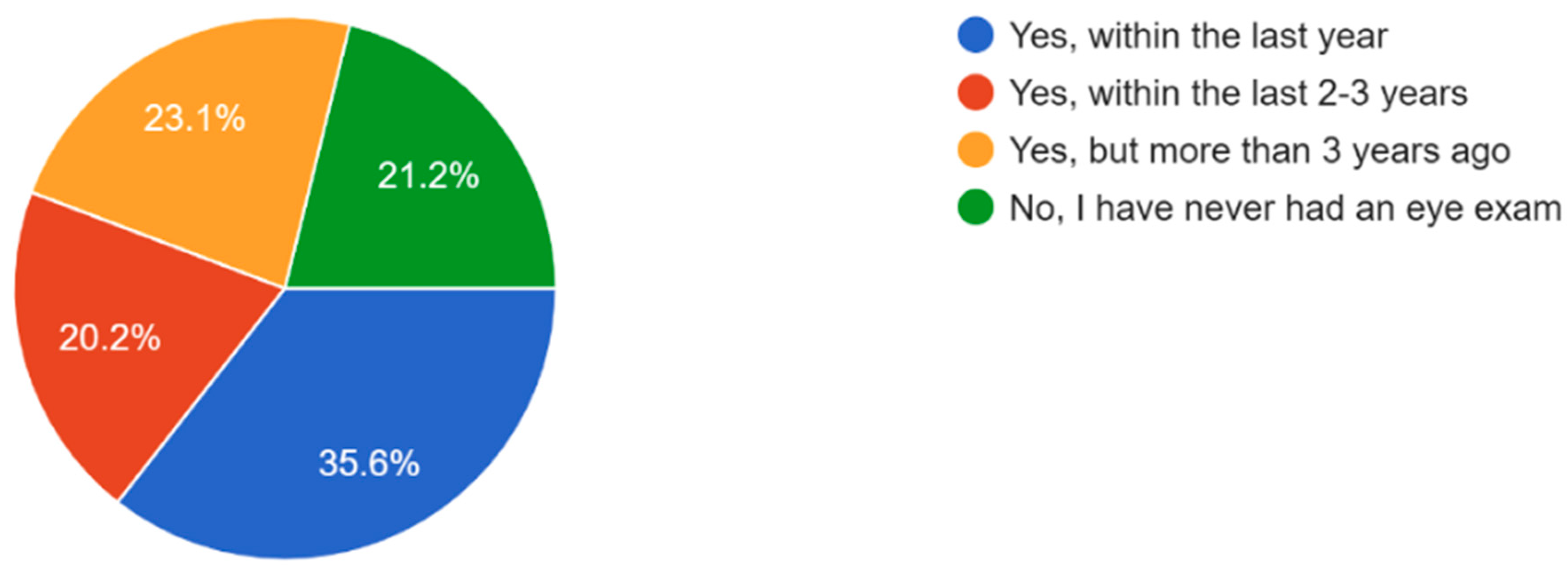

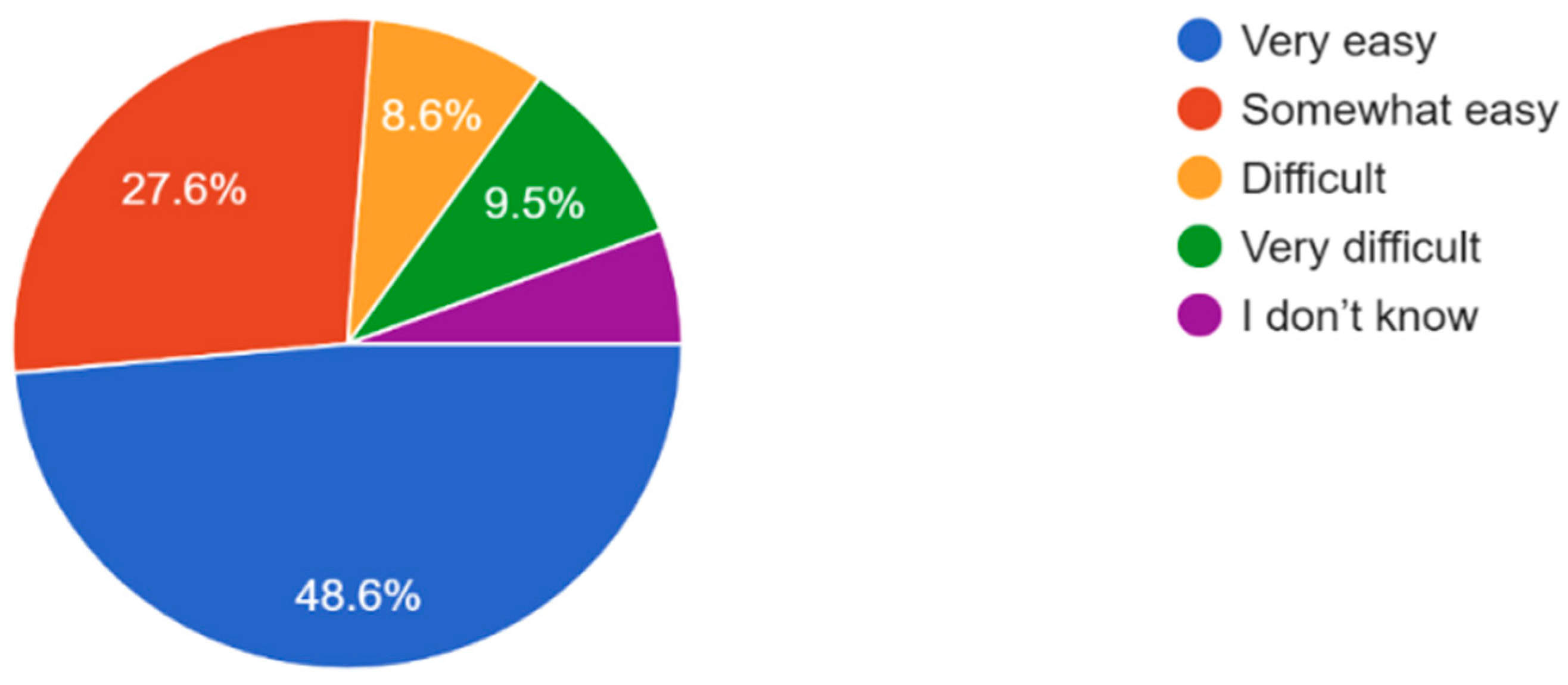

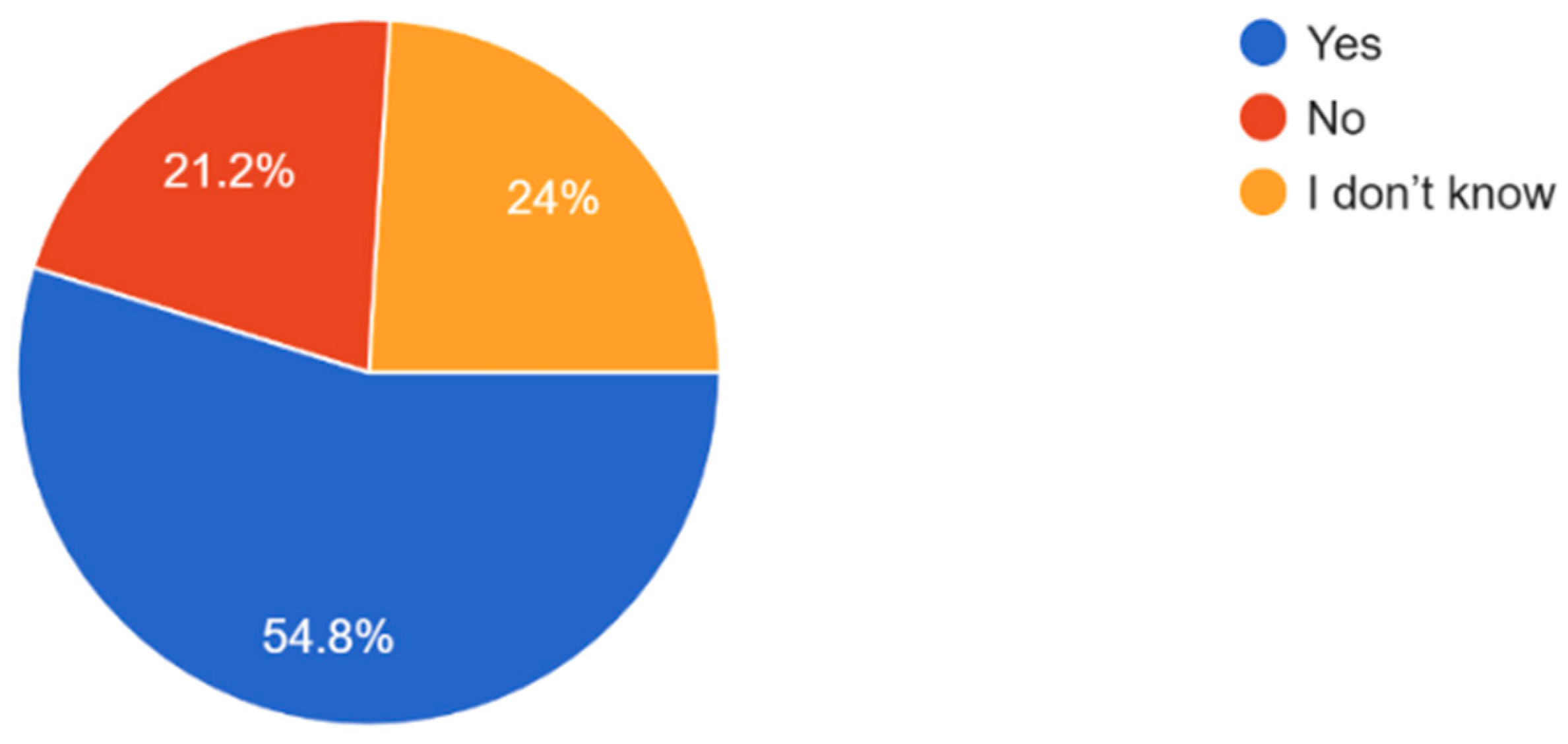

3.1. Eye Health Awareness of Participants

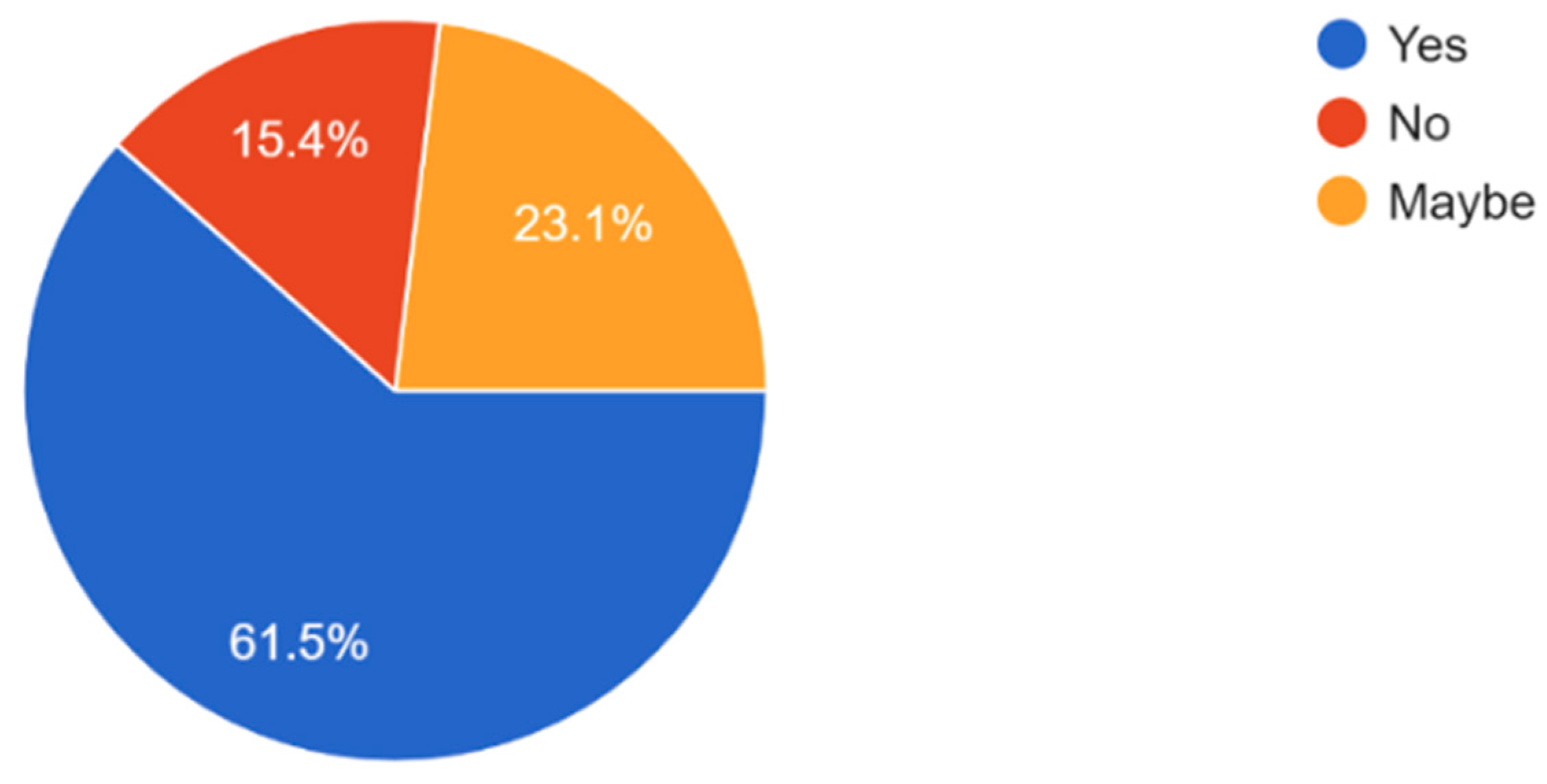

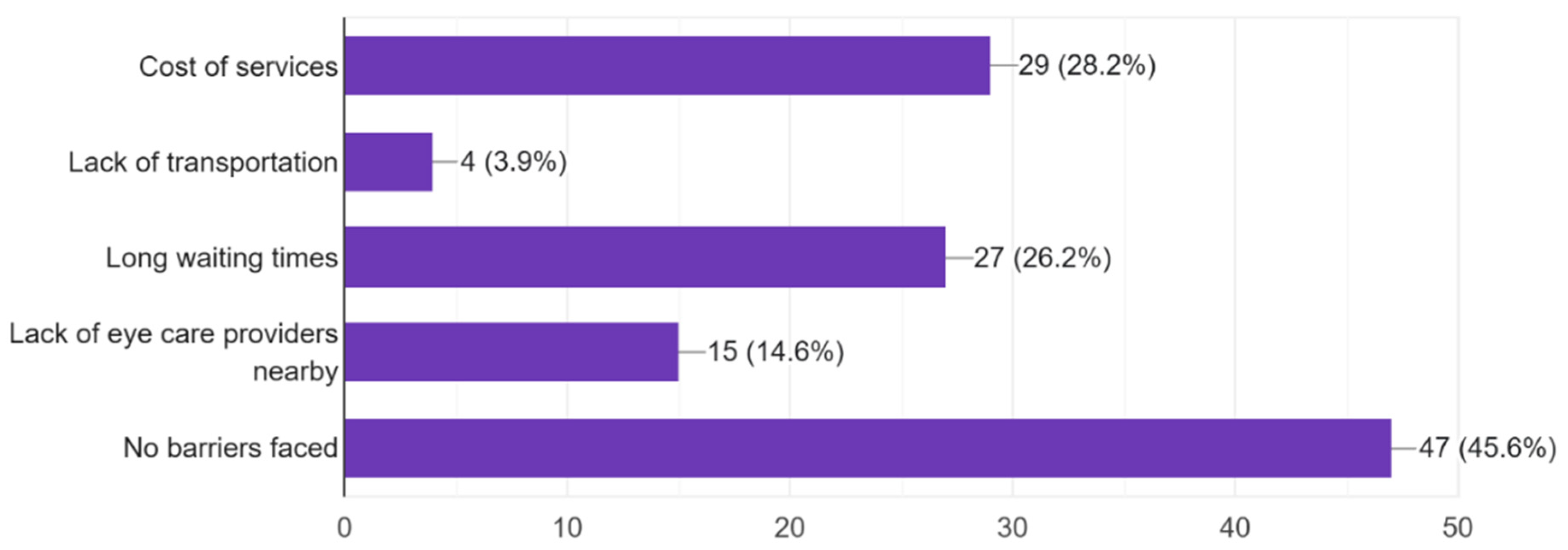

3.2. Barriers to Access Eye Care

4. Discussion

4.1. Identifying Stakeholders

4.2. Building Coalitions and Partnerships

4.3. Proposing Actions: Community Engagement Strategies

4.4. Recommendations for Collaboration with Local, State, and National Organizations

4.5. Communication Strategies for Different Audiences and Sectors

4.6. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vision Impairment and Blindness. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/blindness-and-visual-impairment (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- GBD 2019 Blindness and Vision Impairment Collaborators. Causes of blindness and vision impairment in 2020 and trends over 30 years, and prevalence of avoidable blindness in relation to VISION 2020: The Right to Sight: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e144–e160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricke, T.R.; Tahhan, N.; Resnikoff, S.; Papas, E.; Burnett, A.; Ho, S.M.; Naduvilath, T.; Naidoo, K.S. Global Prevalence of Presbyopia and Vision Impairment from Uncorrected Presbyopia: Systematic Review, Meta-analysis, and Modelling. Ophthalmology 2018, 125, 1492–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackland, P.; Resnikoff, S.; Bourne, R. World blindness and visual impairment: Despite many successes, the problem is growing. Community Eye Health 2017, 30, 71–73. [Google Scholar]

- Allison, K.; Greene, L.; Lee, C.; Patel, D. Uncovering Disparities in Vision Health in Rural vs Urban Areas: Is There a Difference? Med. Res. Arch. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, K.; Patel, D.; Alabi, O. Epidemiology of Glaucoma: The Past, Present, and Predictions for the Future. Cureus 2020, 12, e11686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourne, R.R.A.; Adelson, J.; Flaxman, S.; Briant, P.; Bottone, M.; Vos, T.; Naidoo, K.; Braithwaite, T.; Cicinelli, M.; Jonas, J.; et al. Global Prevalence of Blindness and Distance and Near Vision Impairment in 2020: Progress towards the Vision 2020 targets and what the future holds. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2020, 61, 2317. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, C.Y.; Wang, N.; Wong, T.Y.; Congdon, N.; He, M.; Wang, Y.; Braithwaite, T.; Casson, R.J.; Cicinelli, M.V.; Das, A.; et al. Prevalence and causes of vision loss in East Asia in 2015: Magnitude, temporal trends and projections. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 104, 616–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tham, Y.C.; Li, X.; Wong, T.Y.; Quigley, H.A.; Aung, T.; Cheng, C.Y. Global Prevalence of Glaucoma and Projections of Glaucoma Burden through 2040: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 2081–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewunet, S.A.; Aredo, K.K.; Gedefew, M. Uncorrected refractive error and associated factors among primary school children in Debre Markos District, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Ophthalmol. 2014, 14, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegegn, M.T.; Assaye, A.K.; Belete, G.T. Prevalence, causes and associated factors of visual impairment and blindness among older population in outreach site, Northwest Ethiopia. A dual center cross-sectional study. Afr. Health Sci. 2023, 23, 683–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.M.; Sahel, J.A. Addressing Social Determinants of Vision Health. Ophthalmol. Ther. 2022, 11, 1371–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, M.J.; Ramke, J.; Marques, A.P.; Bourne, R.R.A.; Congdon, N.; Jones, I.; Tong, B.A.M.A.; Arunga, S.; Bachani, D.; Bascaran, C.; et al. The Lancet Global Health Commission on Global Eye Health: Vision beyond 2020. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e489–e551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhudesai, D.; Chen, J.J.; Lim, E. Evaluation of Access to Care Barriers and Their Effect on General Health Status Among Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Adults. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2023, 10, 1178–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elam, A.R.; Tseng, V.L.; Rodriguez, T.M.; Mike, E.V.; Warren, A.K.; Coleman, A.L. Disparities in Vision Health and Eye Care. Ophthalmology 2022, 129, e89–e113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, L.; Reis, T.; Zhang, J.H.; Yusufu, M.; Turnbull, P.R.; Silwal, P.; Kang, M.; Safi, S.; Yee, H.; Kitema, G.F.; et al. Underserved groups could be better considered within population-based eye health surveys: A methodological study. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2024, 173, 111444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S.D.; Shoge, R.Y.; Ervin, A.M.; Contreras, M.; Harewood, J.; Aguwa, U.T.; Olivier, M.M.G. Improving Access to Eye Care: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Ophthalmology 2022, 129, e114–e126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ervin, A.M.; Solomon, S.D.; Shoge, R.Y. Access to Eye Care in the United States: Evidence-Informed Decision-Making Is Key to Improving Access for Underserved Populations. Ophthalmology 2022, 129, 1079–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, S.T.; Finn, A.P.; Parikh, R.; Kuriyan, A.E.; Patel, S. Ophthalmology Workforce Projections in the United States, 2020 to 2035. Ophthalmology 2024, 131, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, C.A.; Nanjan, M.B.; Taylor, H.R. Vision impairment predicts 5 year mortality. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2001, 85, 322–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Committee on Health Care Utilization and Adults with Disabilities. Factors That Affect Health-Care Utilization. In Health-Care Utilization as a Proxy in Disability Determination; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2018. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK500097/ (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Frazier, T.L.; Lopez, P.M.; Islam, N.; Wilson, A.; Earle, K.; Duliepre, N.; Zhong, L.; Bendik, S.; Drackett, E.; Manyindo, N.; et al. Addressing Financial Barriers to Health Care Among People Who are Low-Income and Insured in New York City, 2014–2017. J. Community Health 2023, 48, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazar, M.; Davenport, L. Barriers to Health Care Access for Low Income Families: A Review of Literature. J. Community Health Nurs. 2018, 35, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel, B.A.; Schulz, A.J.; Parker, E.A.; Becker, A.B. Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Ann. Rev. Public Health 1998, 19, 173–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, S.T.; Gerber, B.S.; Sharp, L.K. Traveling Towards Disease: Transportation Barriers to Health Care Access. J. Community Health 2013, 38, 976–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Guideline on Health Policy and System Support to Optimize Community Health Worker Programmes; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK533329/ (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Dam, J.L.; Nagorka-Smith, P.; Waddell, A.; Wright, A.; Bos, J.J.; Bragge, P. Research evidence use in local government-led public health interventions: A systematic review. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2023, 21, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besançon, S.; Sidibé, A.; Sow, D.S.; Sy, O.; Ambard, J.; Yudkin, J.S.; Beran, D. The role of non-governmental organizations in strengthening healthcare systems in low- and middle-income countries: Lessons from Santé Diabète in Mali. Glob. Health Action 2022, 15, 2061239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman Partnership. Home. Available online: https://chapmanpartnership.org/ (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- EyeCare Partners|Ophthalmology and Optometry Practices. Eye Care Partners—Eye Care Partners. 13 July 2022. Available online: https://www.eyecare-partners.com/ (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Solhi, M.; Fard Azar, F.E.; Abolghasemi, J.; Maheri, M.; Irandoost, S.F.; Khalili, S. The effect of educational intervention on health-promoting lifestyle: Intervention mapping approach. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2020, 9, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinowitz, P. Chapter 24, Section 8. Establishing a Peer Education Program—Main Section|Community Tool Box. Available online: https://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/implement/improving-services/peer-education/main (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Vision|Lions Clubs International. Available online: https://www.lionsclubs.org/en/give-our-focus-areas/vision (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- CDC About CDC’s Vision Health Initiative. Vision and Eye Health. 21 May 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/vision-health/cdc-program/index.html (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Teutsh, S.M.; McCoy, M.A.; Woodbury, B.; Welp, A. (Eds.) The Role of Public Health and Partnerships to Promote Eye and Vision Health in Communities. In Making Eye Health a Population Health Imperative: Vision for Tomorrow; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2016. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK402363/ (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Willis, C.D.; Greene, J.K.; Abramowicz, A.; Riley, B.L. Strengthening the evidence and action on multi-sectoral partnerships in public health: An action research initiative. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. Res. Policy Pr. Pract. 2016, 36, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC Visual Communication Resources. Health Literacy. 30 January 2025. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/health-literacy/php/develop-materials/visual-communication.html (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Haldane, V.; Chuah, F.L.H.; Srivastava, A.; Sing, S.R.; Koh, G.C.H.; Seng, C.K.; Legido-Qingley, H. Community participation in health services development, implementation, and evaluation: A systematic review of empowerment, health, community, and process outcomes. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, T.; Kreuter, M.W. Using Written Narratives in Public Health Practice: A Creative Writing Perspective. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2014, 11, E94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Continuing Professional Development: Building and Sustaining a Quality Workforce. In Redesigning Continuing Education in the Health Professions; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2010. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK219809/ (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Dodson, E.A.; Parks, R.G.; Jacob, R.R.; An, R.; Eyler, A.A.; Lee, N.; Morshed, A.B.; Politi, M.C.; Tabak, R.G.; Yan, Y.; et al. Effectively communicating with local policymakers: A randomized trial of policy brief dissemination to address obesity. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1246897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, A.S.; Gillespie, J.A.; Derrick, G.E.; Hall, W.D.; Redman, S.; Chapman, S.; Sturk, H. Galvanizers, Guides, Champions, and Shields: The Many Ways That Policymakers Use Public Health Researchers. Milbank Q. 2011, 89, 564–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Recommendation | Description |

|---|---|

| Increase public health campaigns to raise awareness of common and serious eye conditions. | Implement targeted campaigns to educate the public about common eye conditions like refractive problems, cataracts, glaucoma, macular degeneration, and even rare eye diseases as well as the importance of regular eye exams. |

| Expand access to affordable or free eye care services, including mobile clinics and public health programs. | Increase the availability of affordable eye care services through mobile clinics and public health initiatives to reach underserved populations. |

| Foster partnerships between local healthcare providers, non-profits, and public health organizations to address resource gaps | Develop collaborations between healthcare providers, non-profit organizations, and public health agencies to improve resource availability and coordination of eye care services. |

| Engage community leaders to promote eye health initiatives and create more educational opportunities for the public. | Involve local community leaders in promoting eye health, organizing awareness programs, and creating educational opportunities to raise awareness and improve eye health knowledge. |

| Stakeholder | Role and Contribution |

|---|---|

| Local Healthcare Providers | Doctors, nurses, optometrists, and eye care specialists provide frontline medical attention, diagnostic services, and treatment options to the community. |

| Policymakers | Local and national policymakers influence public health priorities, allocate funding, and set regulations that improve access to eye care and advance policy reforms. |

| Community Leaders | Religious figures, educators, and local influencers hold community trust, spreading awareness and encouraging individuals to seek eye care services. |

| Non-governmental Organizations (NGOs) | NGOs working in health, education, and poverty alleviation provide resources, funding, and advocacy, and can offer specialized services to underserved communities. |

| Public Health Agencies | Local and national public health departments facilitate eye health programs, organize awareness campaigns, and implement screenings, particularly in underserved areas. |

| Strategy | Description |

|---|---|

| Partnership Models | Establish formal partnerships where stakeholders pool resources, knowledge, and networks to achieve specific outcomes such as increasing access or improving awareness. |

| Collaboration Frameworks | Develop clear frameworks that define roles, responsibilities, and expectations, ensuring alignment of contributions towards common goals. |

| Shared Goals and Objectives | Align the vision of all stakeholders towards a unified objective, such as reducing preventable blindness, to create a sense of purpose and drive collaboration. |

| Strategy | Description | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Creating Easy-to-Understand Materials | Develop infographics, fact sheets, and simple brochures that explain common eye conditions, symptoms, and the importance of regular eye exams. | To increase awareness and make eye health information more accessible to a wider audience, including those with limited health literacy. |

| Community Workshops | Organize workshops and community events to educate individuals about eye health, available services, and preventive measures. | To engage the community directly and provide hands-on, interactive learning about eye care and its importance. |

| Public Health Campaigns | Launch media campaigns using radio, TV, social media, and local publications to reach a broader audience. | To raise awareness, build engagement, and inform the public about the risks of poor eye health and available services. |

| Storytelling and Testimonials | Share real-life stories and testimonials from community members or health professionals who have experienced eye health issues or improvement. | To make eye health issues more relatable and motivate individuals to take action, showing that eye health impacts real people. |

| Promoting Free or Low-Cost Services | Distribute information about available subsidized eye care programs, mobile clinics, or local healthcare centers offering affordable services. | To ensure that the underserved community knows about affordable or free eye care options, removing cost barriers to access. |

| Engaging Local Leaders | Involve respected community figures such as religious leaders, teachers, or social workers to deliver eye health messages in culturally appropriate ways. | To leverage trust and familiarity, ensuring that the message resonates within the community and fosters collective action for better eye health. |

| Strategy | Description | Purpose | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Professional Development | Organize training workshops and continuing education sessions focused on current eye care practices, new technologies, and diagnostic tools. | To enhance the knowledge and skills of healthcare providers in the diagnosis and management of eye conditions. | Improved competency in eye care practices and better patient outcomes. |

| Dissemination of Evidence-Based Practices | Share research findings, clinical guidelines, and case studies through newsletters, conferences, or online platforms that highlight evidence-based practices. | To ensure healthcare professionals are using the most current and effective methods in treating eye conditions. | Adoption of best practices and improved clinical decision-making. |

| Collaborative Learning Communities | Create communities of practice or peer learning groups where healthcare professionals can share experiences, discuss challenges, and learn from each other’s insights. | To foster knowledge exchange and mutual support among healthcare professionals. | Enhanced teamwork and shared knowledge to improve patient care. |

| Integration of Eye Health in Primary Care | Provide training for general healthcare providers to incorporate routine eye health screenings and discussions into general health assessments and appointments. | To increase early detection of eye conditions within primary care settings. | Early detection of eye diseases and referral to specialized care when necessary. |

| Digital Tools and Resources | Offer online platforms and mobile apps that provide easy access to the latest research, guidelines, and best practices in eye health for professionals. | To improve accessibility of eye care resources for healthcare professionals. | Streamlined access to up-to-date resources, facilitating quicker and better decision-making. |

| Multidisciplinary Training | Organize training programs that involve professionals from different sectors (e.g., optometrists, ophthalmologists, public health workers) to learn about eye health together. | To promote a holistic and integrated approach to eye care. | Enhanced coordination and collaboration among professionals for better patient care. |

| Strategy | Description | Purpose | Target Audience | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policy Briefs and Presentations | Create concise, evidence-based policy briefs and formal presentations summarizing the need for eye health initiatives, data on eye health disparities, and potential policy interventions. | To inform policymakers of the current state of eye health, the challenges in underserved communities, and the impact of policy reforms. | Policymakers (local, state, and national), health organizations | Increased awareness among policymakers of the need for comprehensive eye health policies and potential legislative actions. |

| Advocacy and Lobbying Strategies | Engage advocacy groups and lobbyists to influence policymakers by presenting compelling evidence, testimonials, and expert opinions on the importance of improving eye care access. | To mobilize stakeholders and build pressure for the implementation of pro-eye health policies, increased funding, and resource allocation. | Advocacy organizations, lobbyists, healthcare providers, local communities | Stronger advocacy for eye health policies, leading to the allocation of resources and funding for eye health programs. |

| Policy Dialogs and Forums | Organize and facilitate policy dialogs or forums that bring together experts, healthcare providers, and policymakers to discuss eye health priorities. | To foster discussions and build consensus on the necessary policy changes needed to improve eye health access and services. | Policymakers, health professionals, community leaders | Creation of a shared policy vision and collaborative efforts to improve eye health. |

| Evidence-Based Advocacy | Provide data-driven reports, research findings, and case studies on successful eye health initiatives and their outcomes. | To convince policymakers that investment in eye health programs will lead to measurable public health improvements and cost savings. | Policymakers, public health agencies, media | Policymakers are more likely to support eye health initiatives based on solid evidence. |

| Public Awareness Campaigns for Policymakers | Use public awareness campaigns to put pressure on policymakers by demonstrating public support for eye health reforms. | To create a public mandate for policymakers to prioritize eye health in policy agendas. | The general public, media, policymakers | Increased public demand for better eye health policies and greater political will to implement reforms. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Allison, K.; Virk, A.; Alamri, A.; Patel, D. Analysis of the Awareness and Access of Eye Healthcare in Underserved Populations. Vision 2025, 9, 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision9030055

Allison K, Virk A, Alamri A, Patel D. Analysis of the Awareness and Access of Eye Healthcare in Underserved Populations. Vision. 2025; 9(3):55. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision9030055

Chicago/Turabian StyleAllison, Karen, Abdullah Virk, Asma Alamri, and Deepkumar Patel. 2025. "Analysis of the Awareness and Access of Eye Healthcare in Underserved Populations" Vision 9, no. 3: 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision9030055

APA StyleAllison, K., Virk, A., Alamri, A., & Patel, D. (2025). Analysis of the Awareness and Access of Eye Healthcare in Underserved Populations. Vision, 9(3), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision9030055