Parental Stress in a Pediatric Ophthalmology Population

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

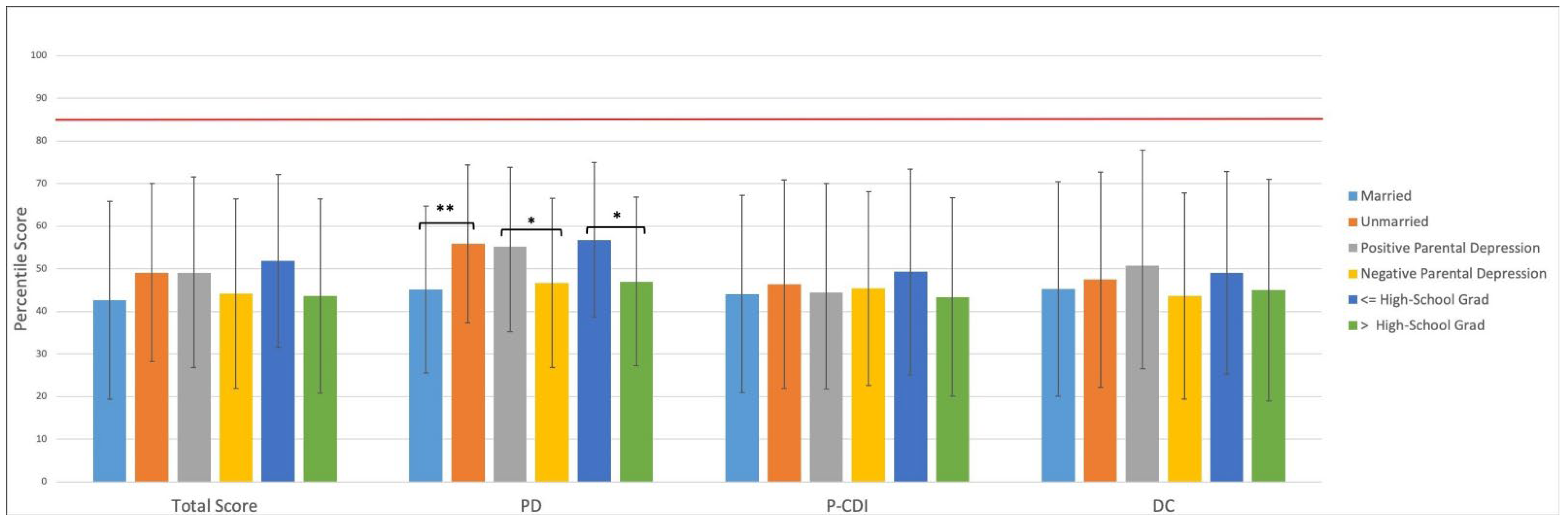

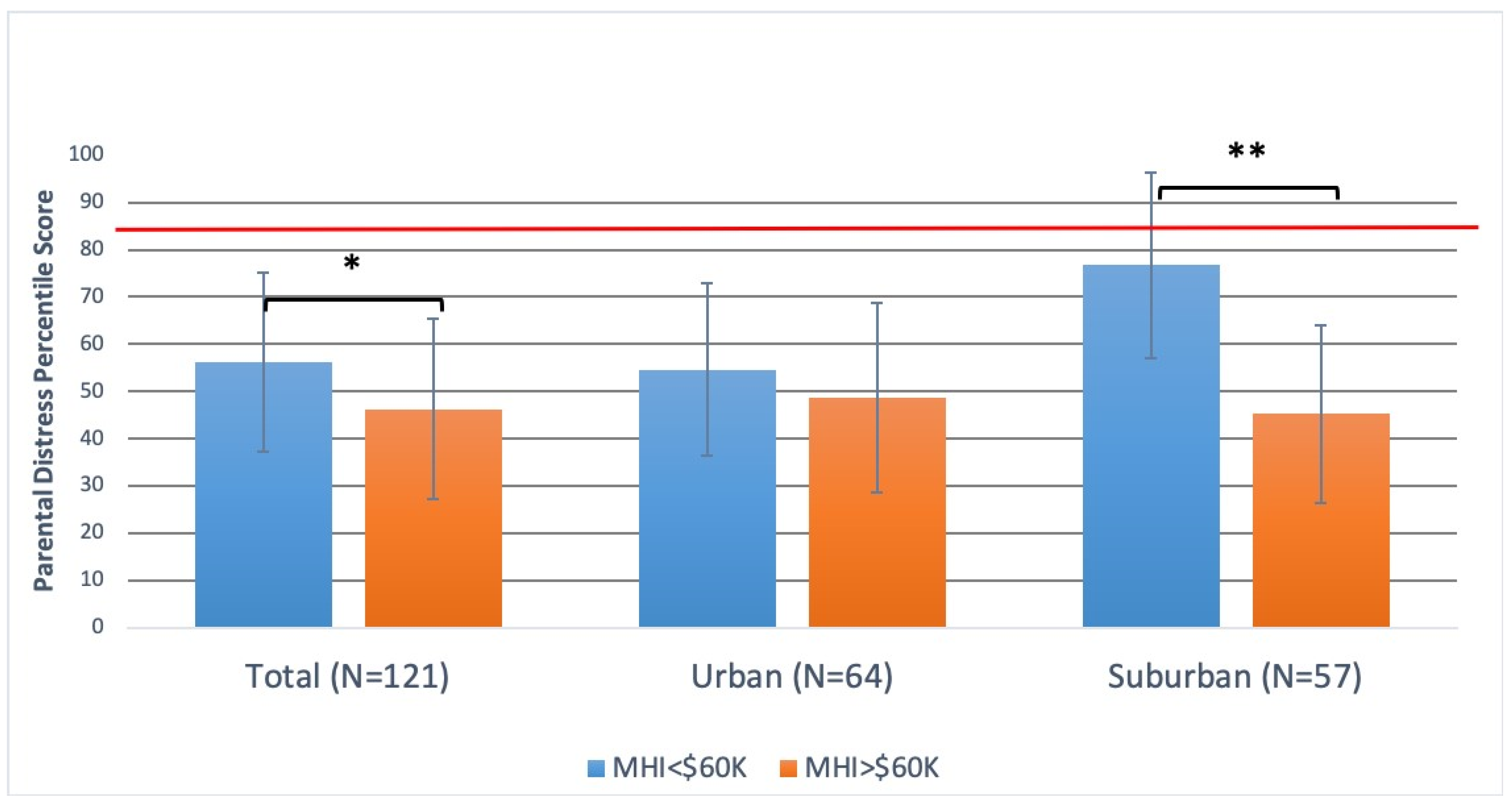

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cousino, M.K.; Hazen, R.A. Parenting stress among caregivers of children with chronic illness: A systematic review. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2013, 38, 809–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, A.; Ostring, G.; Piper, S.; Munro, J.; Singh-Grewa, D. Maternal stress associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2014, 17, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golfenshtein, N.; Srulovici, E.; Medoff-Cooper, B. Investigating parenting stress across pediatric health conditions—A systematic review. Issues Compr. Pediatr. Nurs. 2015, 39, 41–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hile, S.; Erickson, S.J.; Agee, B.; Annett, R.D. Parental stress predicts functional outcome in pediatric cancer survivors. Psychooncology 2014, 23, 1157–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.K.; Wong, A.L.; Cuevas, M.; Van Horn, H. Parenting stress and neurocognitive late effects in childhood cancer survivors. Psychooncology 2013, 22, 1774–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vismara, L.; Rollè, L.; Agostini, F.; Sechi, C.; Fenaroli, V.; Molgora, S.; Neri, E.; Prino, L.E.; Odorisio, F.; Trovato, A.; et al. Perinatal Parenting Stress, Anxiety, and Depression Outcomes in First-Time Mothers and Fathers: A 3- to 6-Months Postpartum Follow-Up Study. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza-Silva, J.C.; Martins, C.A.; Garciazapata, M.T.A.; Barbosa, M.A. Parental stress around ophthalmological health conditions: A systematic review of literature protocol. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bambara, J.K.; Owsley, C.; Wadley, V.; Martin, R.; Porter, C.; Dreer, L.E. Family caregiver social problem-solving abilities and adjustment to caring for a relative with vision loss. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2009, 50, 1585–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrisos, S.; Clarke, M.P.; Wright, C.M. The emotional impact of amblyopia treatment in preschool children: Randomized controlled trial. Ophthalmology 2004, 111, 1550–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willard, V.W.; Qaddoumi, I.; Zhang, H.; Huang, L.; Russell, K.M.; Brennan, R.; Wilson, M.W.; Rodriguez-Galindo, C.; Phipps, S. A longitudinal investigation of parenting stress in caregivers of children with retinoblastoma. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2017, 64, e26279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drews-Botsch, C.; Celano, M.; Cotsonis, G.; Dubois, L.; Lambert, S.R. Parenting stress and adherence to occlusion therapy in the infant aphakia treatment study: A secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2019, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cha, A.E.; Cohen, R.A. Demographic Variation in Health Insurance Coverage: United States, 2020. In National Health Statistics Report; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2022; Volume 169. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, G.W.; Boxhill, L.; Pinkava, M. Poverty and maternal responsiveness: The role of maternal stress and social resources. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2008, 32, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.; McLanahan, S.S.; Meadows, S.O.; Brooks-Gunn, J. Family structure transitions and maternal parenting stress. J. Marriage Fam. 2009, 71, 558–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, U.S.; Park, S.; Yoo, H.J.; Hwang, J.M. Psychosocial distress of part-time occlusion in children with intermittent exotropia. Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2013, 251, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zablotsky, B.; Black, L.I.; Maenner, M.J.; Schieve, L.A.; Danielson, M.L.; Bitsko, R.H.; Blumberg, S.J.; Kogan, M.D.; Boyle, C.A. Prevalence and trends of developmental disabilities among children in the United States: 2009–2017. Pediatrics 2019, 144, e20190811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almogbel, Y.S.; Goyal, R.; Sansgiry, S.S. Association Between Parenting Stress and Functional Impairment Among Children Diagnosed with Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Community Ment. Health J. 2017, 53, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosch, A. Mütterliche belastung bei kindern mit Williams-Beuren-Syndrom, Down-Syndrom, geistiger behinderung nichtsyndromaler ätiologie im vergleich zu der nichtbehinderter kinder. Z Kinder Jugendpsychiatr. Psychother. 2001, 29, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, R.I.; Majnemer, A.; Platt, R.W.; Shevell, M.I. Child Health and Parental Stress in School-Age Children With a Preschool Diagnosis of Developmental Delay. J. Child Neurol. 2008, 23, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, R.R. Parenting Stress Index, 4th ed.; PSI-4; Psychological Assessment Resources: Lutz, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau QuickFacts: Maryland. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/MD (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- Living Wage Calculator-Living Wage Calculation for Baltimore County, Maryland. LivingWage. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Available online: https://livingwage.mit.edu/counties/24005 (accessed on 14 October 2020).

- Uhr, J.H.; Chawla, H.; Williams, B.K., Jr.; Cavuoto, K.M.; Sridhar, J. Racial and Socioeconomic Disparities in Visual Impairment in the United States. Ophthalmology 2021, 128, 1102–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, A.; Richards, C.; Patel, V.; Syeda, S.; Guest, J.M.; Freedman, R.L.; Hall, L.M.; Kim, C.; Sirajeldin, A.; Rodriguez, T.; et al. The Vision Detroit Project: Visual Burden, Barriers, and Access to Eye Care in an Urban Setting. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2022, 29, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, M.L.Z.; Bregman, J.; Ford, J.S.; Shields, C.L. Depression, Anxiety, and Stress in Parents of Patients with Retinoblastoma. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 207, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, A.; Richards, C.; Freedman, R.L.; Rodriguez, T.; Guest, J.M.; Patel, V.; Syeda, S.; Arsenault, S.M.; Kim, C.; Hall, L.M.; et al. The Vision Detroit Project: Integrated Screening and Community Eye-Health Education Interventions Improve Eyecare Awareness. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2023, 30, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total | Urban | Suburban | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | 121 | 64 (52.9%) | 57 (47.1%) | |

| Parent–Female: n (%) | 102 (84.3%) | 55 (85.9%) | 47 (82.5%) | p > 0.05 |

| Parent Age (years) | 37.36 ± 7.37 | 34.89 ± 7.35 | 40.12 ± 6.21 | p < 0.01 |

| AA/Black | 50 | 44 | 6 | p < 0.05 |

| Caucasian | 58 | 13 | 45 | p < 0.05 |

| Hispanic | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Other | 12 | 6 | 6 | |

| Married n (%) | 70 (57.9%) | 20 (31.3%) | 50 (87.7%) | p < 0.01 |

| HS Grad and Less | 34 (28.1%) | 31 (39.1%) | 3 (5.3%) | p < 0.01 |

| Parental Depression | 43 (35.5%) | 28 (48.4%) | 18 (31.6%) | p > 0.05 |

| Patient–Female: n (%) | 62 (51.2%) | 37 (57.8%) | 34 (59.6%) | p > 0.05 |

| Patient Age (Months) | 73.31 ± 49.02 | 63.97 ± 49.77 | 85.49 ± 43.76 | p < 0.05 |

| AA/Black | 50 | 44 | 6 | p < 0.05 |

| Caucasian | 54 | 11 | 43 | p < 0.05 |

| Hispanic | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Other | 16 | 8 | 8 | |

| Median Household Income (MHI) | $66,904.68 ± 23,848.48 | $53,757.08 ± 20,076.99 | $81,460.96 ± 18,767.79 | p < 0.01 |

| MHI ≤ $60 K | 41 (33.9%) | 38 (59.4%) | 3 (5.3%) | p < 0.01 |

| Total Score | 45.9 ± 22.4 | 44.6 ± 22.6 | 47.5 ± 22.1 | p > 0.05 |

| PD | 49.7 ± 19.8 | 52.8 ± 19.0 | 46.3 ± 20.2 | p > 0.05 |

| P-CDI | 45.1 ± 23.6 | 42.7 ± 25.1 | 47.7 ± 21.8 | p > 0.05 |

| DC | 46.2 ± 25.4 | 42.3 ± 25.7 | 50.5 ± 24.5 | p > 0.05 |

| Established Patient | 87 (71.9%) | 37 (57.8%) | 50 (87.7%) | p < 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kalarn, S.; DeLaurentis, C.; Bilgrami, Z.; Thompson, R.; Saeedi, O.; Alexander, J.; Collins, M.L.; Jensen, A.; Notarfrancesco, L.T.; Levin, M. Parental Stress in a Pediatric Ophthalmology Population. Vision 2023, 7, 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision7040069

Kalarn S, DeLaurentis C, Bilgrami Z, Thompson R, Saeedi O, Alexander J, Collins ML, Jensen A, Notarfrancesco LT, Levin M. Parental Stress in a Pediatric Ophthalmology Population. Vision. 2023; 7(4):69. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision7040069

Chicago/Turabian StyleKalarn, Sachin, Clare DeLaurentis, Zaid Bilgrami, Ryan Thompson, Osamah Saeedi, Janet Alexander, Mary Louise Collins, Allison Jensen, Le Tran Notarfrancesco, and Moran Levin. 2023. "Parental Stress in a Pediatric Ophthalmology Population" Vision 7, no. 4: 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision7040069

APA StyleKalarn, S., DeLaurentis, C., Bilgrami, Z., Thompson, R., Saeedi, O., Alexander, J., Collins, M. L., Jensen, A., Notarfrancesco, L. T., & Levin, M. (2023). Parental Stress in a Pediatric Ophthalmology Population. Vision, 7(4), 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision7040069