A Systematic Review of Clinical Practice Guidelines for Cataract: Evidence to Support the Development of the WHO Package of Eye Care Interventions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

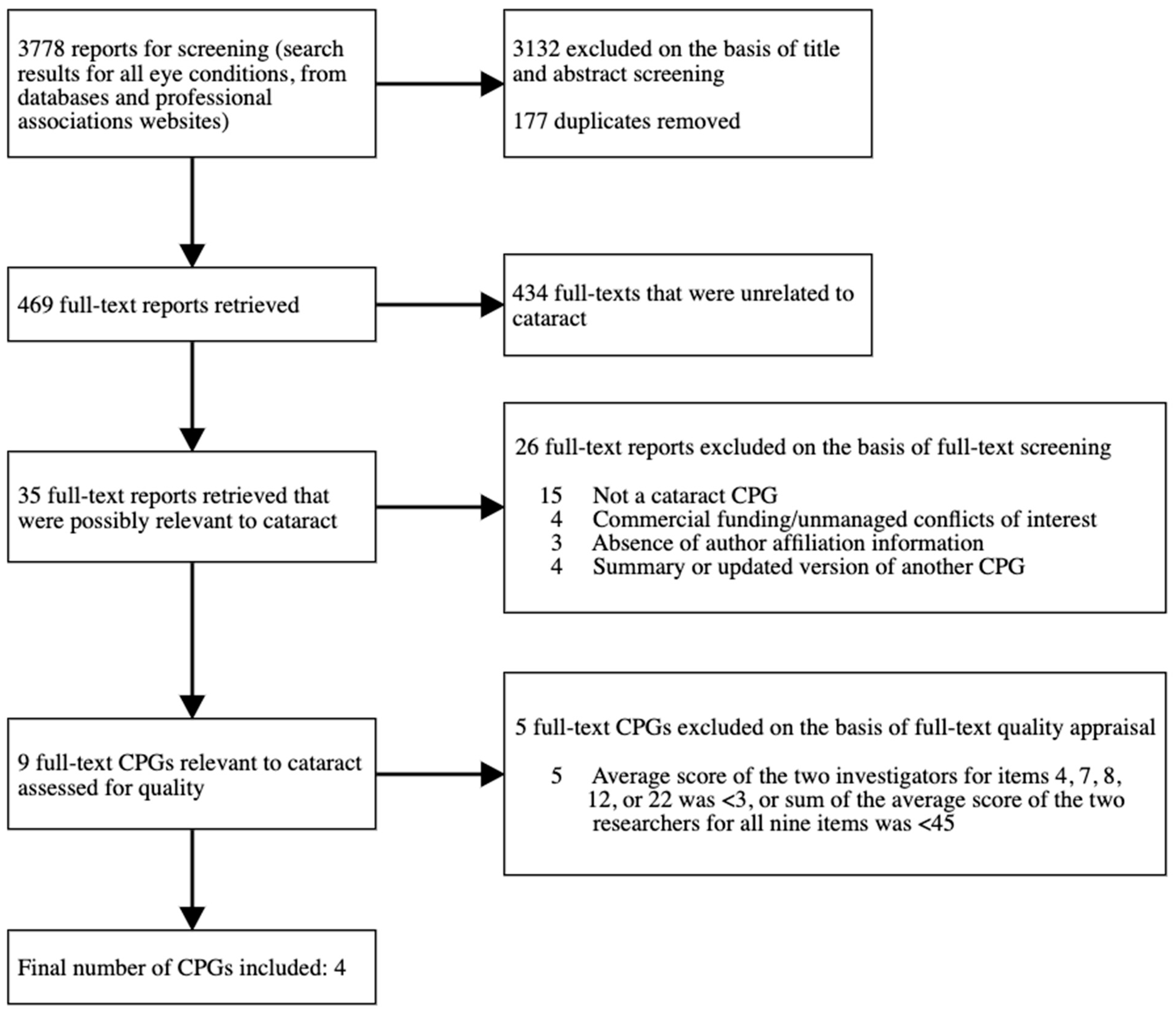

2. Materials and Methods

- Title of the CPG;

- Sponsoring organization (if there was no organization, then the name of the first author was extracted);

- Publication year;

- Title of the chapter to which the recommendation refers to;

- Page number, title and numbering of the section in which the recommendation is stated;

- Intervention target;

- Intervention category;

- Intervention name;

- Who usually provides the intervention;

- Dosage or frequency of the intervention;

- The specific recommendation copied and pasted from the relevant paragraph in the CPG;

- Recommendation strength, and the name or description of the classification system used;

- Quality or level of evidence relating to the recommendation, and the name or description of the classification system used;

- Any other remarks on the recommendation that the investigator believes to be relevant.

3. Results

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2017, Cataracts in adults; management [14].

- American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2016, Cataract in the Adult Eye Preferred Practice Pattern [15].

- Rajavi et al., 2015, Customized clinical practice guidelines for management of adult cataract in Iran [16].

- The Royal College of Ophthalmologists and Clinical Council for Eye Health Commissioning, 2018, Commissioning guide: Adult cataract surgery [17].

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Disclaimer

Appendix A

| Description of Intervention | Relevant CPG(s) * | Quality of Evidence ** | Strength of Recommendation (Strong, Discretionary) *** |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-operative interventions | |||

| Cataract surgery is indicated in patients with cataracts causing vision loss, phacomorphic glaucoma, lens-induced uveitis, or posterior segment diseases where the cataract is limiting the retinal examination/treatment. | 3 | IV | - |

| Patients should be given oral and written information about cataract surgery, in an accessible format. | 1 | Moderate | Strong |

| 4 | - | - | |

| Weigh up the indications, risks, and benefits of cataract surgery with the patient. | 1 | High | Strong |

| 3 | I | - | |

| In patients with cataract in only one eye, surgery is recommended if the advantages outweigh the risks. | 3 | III | - |

| Do not restrict access to cataract surgery based on visual acuity; it should be based on individual need. | 1 | High | Strong |

| 4 | - | - | |

| For patients who require a certain visual acuity for their occupation, cataract surgery is indicated even when the patient does not experience functional deficits. | 3 | IV | - |

| Offer second eye cataract surgery using the same criteria as for first eye surgery. | 1 | Moderate to high | Strong |

| In some cases of anisometropia, earlier surgical intervention for the second eye is recommended, but the time between surgeries should be long enough to first eye surgical complications. | 3 | IV | - |

| In patients with bilateral cataract, it is recommended that surgery is performed in separate sessions to achieve better binocular vision. | 3 | I | - |

| In patients with bilateral cataract, it is recommended that surgery is performed in separate sessions due to the risk of endophthalmitis and toxic anterior segment syndrome. | 3 | III | - |

| Immediate sequential bilateral cataract surgery should be considered for people who are at low risk of operative and post-operative complications, and for people who require general anaesthesia. Potential benefits and risks should be fully discussed with patients pre-operatively. | 1 | Low to moderate | Discretionary |

| 4 | - | - | |

| Cataract surgery may reduce intraocular pressure in patients with angle closure glaucoma | 3 | II | - |

| Simultaneous cataract and glaucoma surgery is recommended if there is a risk of blindness due to increased intraocular pressure post-operatively. | 3 | IV | - |

| Use biometry (preferably optical biometry over ultrasound biometry) and keratometry to estimate axial length and central corneal curvature, respectively. | 1 | Low | Strong |

| 2 | III, good quality | Strong | |

| 3 | I | - | |

| Repeat A-scan biometry if: the axial length is >26 mm or <21 mm; keratometry is >47 D or <41 D; astigmatism is >2.5 D; axial length difference between the two eyes is >0.7; keratometry difference between the two eyes is >0.9. | 3 | III | - |

| Consider corneal topography for people with irregular astigmatism or previous refractive surgery | 1 | Low | Discretionary |

| For patients with previous refractive surgery, use adjusted formulas to calculate the intraocular lens power. Advise them that refractive outcomes after cataract surgery are difficult to predict. | 1 | Very low to moderate | Strong |

| 3 | IV | - | |

| Documentation should be kept by the treatment centre for all patients undergoing refractive surgery. | 3 | II | - |

| Surgeons should consider optimizing a manufacturer’s recommended intraocular lens constant, e.g., based on their previous refractive outcomes. | 1 | low | Strong |

| 3 | IV | - | |

| Consider using the first-eye refractive outcome to guide calculations for the intraocular lens power for second-eye cataract surgery. | 1 | Very low to low | Discretionary |

| In eyes with abnormal size, use Holladay 2 or Haigis formulas. | 3 | IV | - |

| Use new generation formulas to calculate the intraocular lens power. | 3 | III | - |

| Patients should be informed of the potential inaccuracy of intraocular lens power calculations and that further surgery may be required to achieve the target refractive outcome. | 2 | III, good quality | Strong |

| Consider using a validated risk stratification algorithm to identify people at increased risk of complications during and after surgery. | 1 | Low | Discretionary |

| Explain the results of risk stratification to the patient and discuss how it may affect decision-making. | 1 | Low | Strong |

| In cases where the cataract surgery is likely to be complex, and there may be a high risk of complications, or the surgeon is not experienced enough, the surgery should be performed by a more experienced surgeon or the patient should be referred to a facility with more expertise. | 3 | II | - |

| If a retinal detachment is found on pre-assessment, consider combined vitrectomy and cataract surgery. | 3 | III | - |

| In patients with Fuchs’ dystrophy and cataract, combined cataract and corneal transplant can be considered. | 3 | IV | - |

| If possible, phacoemulsification should be performed before penetrating keratoplasty if visualization is adequate. | 2 | III, good quality | Strong |

| Explain to people who are at risk of developing dense cataracts that delayed surgery can result in an increased risk of complications. | 1 | Low | Strong |

| 2 | III, good quality | Strong | |

| Do not offer multifocal intraocular lenses for patients with cataracts. | 1 | Very low to moderate | Strong |

| The suitability of multifocal intraocular lenses for patients with amblyopia, or abnormalities of the cornea, optic nerve or macula must be carefully considered. | 2 | III, insufficient quality | Discretionary |

| Offer monovision to patients with anisometropia, or pre-operative monovision. | 1 | Very low to moderate | Strong |

| Assess tear function, as tear dysfunction may compromise the postoperative result. | 2 | II+, good quality | Strong |

| Counsel patients to stop smoking. | 2 | II+, good quality | Strong |

| 3 | I | - | |

| Recommend brimmed hats and ultraviolet-B blocking sunglasses. | 2 | II-, good quality | Strong |

| 3 | I | - | |

| Recommend safety eyeglasses in high-risk activities at work or recreation. | 2 | III, good quality | Strong |

| Advise patients that currently there is insufficient evidence to support the use of pharmacological treatments for cataract. | 2 | III, good quality | Strong |

| Advise patients that long-term use of steroids is associated with increased risk of cataract. | 2 | II+, moderate quality | Strong |

| 3 | I | - | |

| Vitamin supplements do not reduce the progression of cataracts. | 3 | I | - |

| Increased risk of cataracts should be discussed with diabetic patients. | 3 | II | - |

| In patients with cataracts who do not want surgery, the increased risk of accidents and bone fractures should be discussed. | 3 | II | - |

| Patients with cataracts should undergo surgery as soon as possible, preferably with a waiting time of less than 2–3 months to avoid possible falls, fractures and accidents. | 3 | I | - |

| In a functionally monocular patient, tell the patient that blindness is one of the risks of cataract surgery. | 2 | III, good quality | Strong |

| Patients should be informed pre-operatively regarding the possibility of visual impairment continuing after surgery. | 2 | III, good quality | Strong |

| A medical pre-operative evaluation should be performed by the surgeon, and where appropriate, the primary care physician, to determine the appropriateness and timing of surgery. | 2 | III, good quality | Strong |

| 3 | I | - | |

| Pre-operative laboratory testing is not indicated. | 2 | I+, good quality | Strong |

| Consider the patient’s preferences and needs when selecting the post-operative refractive target. | 1 | Moderate | Strong |

| 2 | III, good quality | Strong | |

| α-1 antagonists should be discontinued before surgery due to the high risk of floppy iris syndrome. | 3 | II | - |

| Anti-coagulant and anti-platelet medications should generally be continued. | 2 | I-, good quality | Strong |

| For patients on warfarin, the international normalized ratio should be in the therapeutic range. | 2 | I+, good quality | Strong |

| Aspirin should only be discontinued peri-operatively if the risk of bleeding outweighs its potential benefit. | 2 | I-, good quality | Strong |

| Discontinuation of anti-coagulant medications is not recommended, except for warfarin and clopidogrel. | 3 | I | - |

| Documentation of which eye is being operated on, IOL power, medications, previous diseases, etc, should be filled in immediately before surgery. | 3 | II | - |

| All patients with cataracts should be informed about the risk of posterior capsular opacification before undergoing surgery. | 3 | III | - |

| The risk of aggravation of diabetic retinopathy should be discussed in patients with diabetes who are undergoing cataract surgery. | 3 | III | - |

| If possible, treatment of proliferative diabetic retinopathy and macular oedema should be carried out before cataract surgery. | 3 | IV | - |

| Risk of retinal detachment should be discussed with high-risk patients, e.g., young, male, high myope. | 3 | I | - |

| Patients with age-related macular degeneration should only undergo cataract surgery is there is a chance for improved vision, and the patient should be informed of the risk of worsening of their macular degeneration. | 3 | I | - |

| Patients should be counselled prior to surgery if they have a comorbidity that is associated with intra-ocular complications or the potential for reduced improvement in visual function. | 2 | III, good quality | Strong |

| In patients with uveitis, inflammation should be at its best level of control, for ≥3 months prior to elective surgery, and anti-inflammatory medications should be started prior to surgery. The medical regimen should be individualized, based on the severity of previous episodes of uveitis. | 2 | III, good quality | Strong |

| In patients with uveitis, surgical planning should take into account the possible need for further procedures secondary to uveitis complications, e.g., secondary glaucoma. | 2 | III, good quality | Strong |

| Ensure that the correct medical notes are used by confirming the patient’s name, address and date of birth, and ensure that biometry results are securely attached to the patient’s notes. Record the patient’s choice of refractive outcome in the medical notes. | 1 | Moderate | Strong |

| Staff in the cataract pathway should be able to provide evidence of competencies and continuing professional development. | 4 | - | - |

| While certain diagnostic procedures may be delegated to appropriately trained staff supervised by the ophthalmologist, interpretation of these procedures requires the clinical judgement of the ophthalmologist. | 2 | III, good quality | Strong |

| Intra-operative interventions | |||

| The predominant method of cataract surgery in high income countries is small incision phacoemulsification with foldable intraocular lens implantation. | 2 | I+, good quality | Strong |

| 3 | I | - | |

| Small incision surgery is generally preferred. | 2 | I-, good quality | Strong |

| Only an ophthalmologist has the medical and microsurgical training as part of a comprehensive resident experience needed to perform cataract surgery. | 2 | III, good quality | Strong |

| Ensure that surgeons in training are well supervised. | 1 | Low | Strong |

| Local anaesthesia is preferred, but in some cases general anaesthesia is indicated. | 2 | I++, good quality | Strong |

| Offer sub-Tenon’s or topical anaesthesia. | 1 | Very low to high | Strong |

| Consider hyaluronidase as an adjunct to sub-Tenon’s anaesthesia | 1 | Low | Discretionary |

| If both sub-Tenon’s and topical are contraindicated, consider peribulbar anaesthesia. | 1 | Very low to high | Discretionary |

| Do no offer retrobulbar anaesthesia. | 1 | Very low to high | Strong |

| Consider sedation as an adjunct to anaesthesia for people who are anxious, have postural problems, or where surgery is expected to take longer than usual. | 1 | Low | Discretionary |

| There is insufficient evidence to recommend sedation over local anaesthesia. | 2 | I+, good quality | Strong |

| When sedation is used, intravenous access is recommended. | 2 | I+, good quality | Strong |

| The choice of local anaesthesia is based on patient and surgeon preference. | 2 | I+, good quality | Strong |

| 3 | I | - | |

| Monitoring during administration of anaesthesia generally includes a heart monitor, pulse oximetry, blood pressure and respiratory rate, performed by a qualified staff member. | 2 | III, good quality | Strong |

| Before giving anaesthesia, use a WHO surgical safety checklist to check the patient’s identity, consent form, printed biometry results, medical notes, preferred refractive outcome, lens, marked eye to be operated on, and consistency of lens formulas and calculations. | 1 | Moderate | Strong |

| Ensure there is only one matching intraocular lens in the theatre, and that alternative intraocular lenses (e.g., noncapsular-bag lenses) are in stock in the event of surgical complications. | 1 | Moderate | Strong |

| 2 | III, good quality | Strong | |

| As non-capsular bag fixation may increase the potential for optic tilt/decentration, the surgeon should consider whether multifocal intraocular lenses or lenses with higher degrees of negative spherical aberration should be used. | 2 | III, insufficient quality | Discretionary |

| A peripheral iridectomy should be performed to prevent the risk of pupillary block associated with an anterior chamber intraocular lens. | 2 | III, good quality | Strong |

| Consider on-axis surgery or limbal-relaxing incisions to reduce astigmatism. | 1 | Moderate | Discretionary |

| Only use femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery as part of a randomized control trial. | 1 | Low | Strong |

| There are certain types of cataracts, e.g., posterior polar, for which the femtosecond laser should not be used. | 2 | II-, moderate quality | Strong |

| In patients at risk of floppy iris syndrome, consider intracameral phenylephrine to increase pupil size. | 1 | Low | Discretionary |

| Follow a protocol for posterior capsule rupture that covers vitreous removal from the anterior chamber, minimizing retinal traction, lens fragment and soft lens matter removal, and implications of intraocular lens insertion. | 1 | No evidence was identified | Strong |

| Do not use capsular tension rings in routine cataract surgery. | 1 | High | Strong |

| Consider use of capsular tension rings in patients with pseudoexfoliation. | 1 | High | Discretionary |

| Use pre-operative anti-septics, and commercially or pharmacy prepared intracameral cefuroxime, to prevent endophthalmitis. | 1 | Very low to high | Strong |

| 2 | I-, good quality | Strong | |

| Intracameral antibiotic injections are not recommended due to the toxic effects and likelihood of reduction in corneal endothelial cells. | 3 | III | - |

| Discourage use of antibiotic in the irrigation bottle. | 2 | III, moderate quality | Strong |

| Construct and close incisions so that they are watertight, to reduce risk of infection. | 2 | II-, moderate quality | Strong |

| Eyelashes should be prepped with 10% povidone-iodine. | 3 | II | - |

| The conjunctiva should be prepped with 5% povidone-iodine. | 2 | II-, moderate quality | Strong |

| 3 | II | - | |

| In immediate sequential bilateral cataract surgery, the second eye should be treated as the eye of a different patient would be treated, using separate prepping, draping, instrumentation, irrigation solutions, and medications. | 2 | III, good quality | Strong |

| In patients with planned immediate sequential bilateral cataract surgery, if a complication occurs during first eye surgery, then second eye surgery should be reconsidered and carried out at a later date. | 2 | III, good quality | Strong |

| The surgeon should avoid working close to the cornea. | 2 | III, good quality | Strong |

| The surgeon should ensure proper orientation of the intraocular lens. | 2 | III, good quality | Strong |

| If there is vitreous loss, the surgeon should perform an anterior vitrectomy and implant an intraocular lens with appropriate size and design. | 2 | III, good quality | Strong |

| In patients with uveitis, excessive iris manipulation should be minimized and post-operative short-acting topical mydriatic agents may help prevent synechiae formation. Adjunctive steroids at the time of surgery should be considered. | 2 | III, good quality | Strong |

| Use intraocular lenses with sharp angles to reduce the risk of posterior capsule opacity. | 3 | I | - |

| Use of aspheric intraocular lenses is recommended to achieve better contrast sensitivity and visual performance; but in conditions such as zonular rupture, astigmatism, or after hyperopic corneal refractive surgery, spherical intraocular lenses should be implanted. | 3 | I | - |

| In the process of using multifocal intraocular lenses, careful patient selection, consultation, and utilization of preoperative examinations are vital. | 3 | IV | - |

| Base the use of multifocal/adjustable lenses on patient needs and desires, and after giving the patient information about the advantages and disadvantages. | 3 | I | - |

| To use toric intraocular lenses in patients with astigmatism, accurate preoperative calculations, correct marking of the steep axis, and implanting the intraocular lenses in correct axis should be considered. | 3 | IV | - |

| Visual outcomes after implantation of UV filter intraocular lenses and blue filter intraocular lenses are comparable. | 3 | I | - |

| When the posterior chamber intraocular lenses is placed in the ciliary sulcus, decreasing the power by 0 to 1.5 dioptres should be considered. | 3 | IV | - |

| Staining of the anterior capsule is recommended in mature cataracts, complicated cataracts and paediatric cataracts. | 3 | I | - |

| A smaller capsulorhexis (4.5–5 mm) is preferable to a larger one since it decreases the chance of posterior capsule opacification. | 3 | I | - |

| It is recommended that hydrodissection and hydrodelineation be performed to reduce tension on the zonules, facilitate cortex removal, and reduce the chance of posterior capsule opacification. | 3 | I | - |

| Floppy iris syndrome can be anticipated in patients using oral α-1 antagonists, and pharmacologic approaches, viscomydriasis, and pupil-expansion devices should be used to manage floppy iris syndrome. | 2 | II-, moderate quality | Strong |

| 3 | I | - | |

| A small pupil should be enlarged, e.g., with hooks/rings. | 3 | IV | - |

| Performing phacoemulsification with a torsional probe is preferable to longitudinal probes since there is a smaller risk of corneal trauma. | 3 | I | - |

| In patients with zonular weakness, applying capsular tension rings is recommended. | 3 | I | - |

| It is recommended to implant intraocular lenses using injectors. | 3 | III | - |

| In the absence of inadequate capsular bag support, the surgeon should determine a suitable intraocular lens to be implanted into the ciliary sulcus. Implantation of multifocal and aspheric intraocular lenses in the ciliary sulcus are not recommended. | 3 | III | - |

| In cases of posterior capsular rupture and inadequate capsular support for in-the-bag intraocular lens implantation, anterior chamber intraocular lenses, scleral fixation posterior chamber intraocular lenses, or iris fixation intraocular lenses may be used. | 3 | III | - |

| Subconjunctival antibiotic injection may be recommended to reduce the chance of postoperative endophthalmitis. | 3 | III | - |

| Post-operative interventions | |||

| The operating ophthalmologist should provide aspects of post-operative care that are within their competence, and should inform patients about the symptoms of possible complications and details regarding their post-operative care. This includes instructions to notify the ophthalmologist promptly if problems occur. | 2 | III, good quality | Strong |

| At the first review appointment after cataract surgery, give patients information about eye drops, what to do if their vision changes, who to contact for queries, when to buy new spectacles, second eye cataract surgery, how to manage ocular comorbidities. | 1 | Low | Strong |

| It is recommended to perform the first post-operative examination up to 24 h after the surgery. The exact timing of other postoperative visits depends on surgical complications, and surgeon and patient preference. | 3 | IV | - |

| In high risk conditions such as monocular patients, glaucomatous eyes and surgical complications, the first post-operative visit should be performed within 24 h and more frequent follow-up examinations are needed. | 3 | IV | - |

| Patients should always have access to an ophthalmologist. | 2 | III, good quality | Strong |

| A final refractive visit should be made to provide a prescription for spectacles. | 2 | III, good quality | Strong |

| Final evaluation of refractive power should be performed 2 weeks post-operatively in patients with small corneal incisions (under 3.5 mm) and 6 weeks post-operatively in patients with larger incisions or extracapsular surgery. | 3 | IV | - |

| If a surgeon encounters a higher incidence of endophthalmitis compared to what is reported in the literature, the source of this should be investigated by taking microbial cultures from the personnel, surgery room and devices. | 3 | IV | - |

| Patient education brochures should be given to patients after surgery. | 3 | II | - |

| Providers of cataract care should be able to provide commissioners with outcome data, and outcome data from primary care should be fed back to the surgical team. Providers and surgeons should use audit tools to monitor quality, outcomes and adverse events in real time. | 1 | Low | Strong |

| 4 | - | - | |

| The surgical facility should comply with local and state regulations and standards. | 2 | III, good quality | Strong |

| Costlier new infection control measures that do not have evidence-based support should not be arbitrarily imposed by regulatory agencies. | 2 | III, good quality | Strong |

| If a wrong lens is implanted, refer to NHS England’s Never Events policy, undertake a root-cause analysis, and establish strategies and implementation tools to prevent future occurrences. | 1 | Moderate | Strong |

| Offer topical steroids or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs after cataract surgery in patients at risk of cystoid macular oedema. | 1 | Very low to low | Strong |

| 3 | I | - | |

| Consider topical steroids in combination with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs after cataract surgery in patients at risk of cystoid macular oedema. | 1 | Very low to low | Discretionary |

| Intraocular pressure should be monitored in patients treated with post-operative corticosteroids. | 2 | II-, good quality | Strong |

| In high-risk patients, e.g., pre-existing glaucoma, the intraocular pressure should be monitored in the early post-operative period and appropriate pressure-lowering agents given. | 2 | III, good quality | Strong |

| There is no evidence that visual outcome is improved by routine use of prophylactic non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs at ≥3 months after cataract surgery. | 2 | II+, moderate quality | Strong |

| Offer eye protection for patients whose eye shows residual effects of anaesthesia at time of discharge after surgery. | 1 | No evidence was identified | Strong |

| Consider collecting visual function and quality of life data for entry into an electronic dataset. | 1 | Low | Discretionary |

| Do not offer face-to-face first-day review to patients who had uncomplicated cataract surgery. | 1 | Low | Strong |

| If endophthalmitis is suspected, refer to a retina specialist to review the patient within 24 h. If review within 24 h is not possible, perform an intravitreal tap and inject of antibiotics. | 2 | I-, good quality | Strong |

| When unacceptable refractive error results after lens implantation, the risks of further surgery must be weighed against use of spectacles or contact lens correction. | 2 | III, good quality | Strong |

| Patients with uveitis generally require greater frequency and duration of topical anti-inflammatory treatment and should be monitored closely. | 2 | III, good quality | Strong |

| YAG laser capsulotomy is indicated for posterior capsular opacification where there is a functional impact. The eye should be inflammation-free and the IOL stable prior to performing a YAG capsulotomy. | 2 | III, good quality | Strong |

| High frequency post-operative antibiotics are recommended. | 3 | III | - |

| Topical steroids or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to reduce post-operative inflammation is recommended. | 3 | IV | - |

| Ophthalmologists should be aware of resistance to several antibiotics such as penicillin and fluoroquinolones for treatment of postoperative staphylococcal endophthalmitis. | 3 | III | - |

| Ophthalmologists should be aware of toxic anterior segment syndrome and its predisposing factors. | 3 | III | - |

| To evaluate patient satisfaction, standard questionnaires such as the VF14 will provide greater insight into patient satisfaction than visual acuity assessment. | 3 | IV | - |

References

- World Health Organization. World Report on Vision; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Keel, S.; Evans, J.R.; Block, S.; Bourne, R.; Calonge, M.; Cheng, C.Y.; Friedman, D.S.; Furtado, J.M.; Khanna, R.C.; Mathenge, W.; et al. Strengthening the integration of eye care into the health system: Methodology for the development of the WHO package of eye care interventions. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2020, 5, e000533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2019 Blindness and Vision Impairment Collaborators on behalf of the Vision Loss Expert Group of the Global Burden of Disease Study. Causes of blindness and vision impairment in 2020 and trends over 30 years, and prevalence of avoidable blindness in relation to VISION 2020: The Right to Sight: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e144–e160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Integrated people-centred eye care, including preventable vision impairment and blindness: Global targets for 2030. Seventy-fourth World Health Assembly. In Integrated People-Centred Eye Care, Including Preventable Vision Impairment and Blindness: Global Targets for 2030. Seventy-Fourth World Health Assembly; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ramke, J.; Gilbert, C.E.; Lee, A.C.; Ackland, P.; Limburg, H.; Foster, A. Effective cataract surgical coverage: An indicator for measuring quality-of-care in the context of Universal Health Coverage. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Keel, S.; Muller, A.; Block, S.; Bourne, R.; Burton, M.J.; Chatterji, S.; He, M.; Lansingh, V.C.; Mathenge, W.; Mariotti, S.; et al. Keeping an eye on eye care: Monitoring progress towards effective coverage. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e1460–e1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, Y.; de Silva, S.R.; Evans, J.R. Manual small incision cataract surgery (MSICS) with posterior chamber intraocular lens versus phacoemulsification with posterior chamber intraocular lens for age-related cataract. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 10, CD008813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Riaz, Y.; Mehta, J.S.; Wormald, R.; Evans, J.R.; Foster, A.; Ravilla, T.; Snellingen, T. Surgical interventions for age-related cataract. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2006, 4, CD001323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaggernath, J.; Gogate, P.; Moodley, V.; Naidoo, K.S. Comparison of cataract surgery techniques: Safety, efficacy, and cost-effectiveness. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 24, 520–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yan, W.; Fotis, K.; Prasad, N.M.; Lansingh, V.C.; Taylor, H.R.; Finger, R.P.; Facciolo, D.; He, M. Cataract Surgical Rate and Socioeconomics: A Global Study. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2016, 57, 5872–5881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AGREE Next Steps Consortium. The AGREE II Instrument [Electronic Version]. 2017. Available online: https://www.agreetrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/AGREE-II-Users-Manual-and-23-item-Instrument-2009-Update-2017.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Rauch, A.; Negrini, S.; Cieza, A. Toward Strengthening Rehabilitation in Health Systems: Methods Used to Develop a WHO Package of Rehabilitation Interventions. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2019, 100, 2205–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Cataract in Adults: Management. NICE Guideline NG77; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Ophthalmology. Cataract in the Adult Eye Preferred Practice Pattern; American Academy of Ophthalmology: Chicago, IL, USA, 2016. Available online: https://gmcboard.vermont.gov/sites/gmcb/files/Cataract%20in%20the%20Adult%20Eye%20PPP.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Rajavi, Z.; Javadi, M.A.; Daftarian, N.; Safi, S.; Nejat, F.; Shirvani, A.; Ahmadieh, H.; Shahraz, S.; Ziaei, H.; Moein, H.; et al. Customized Clinical Practice Guidelines for Management of Adult Cataract in Iran. J. Ophthalmic. Vis. Res. 2015, 10, 445–460. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- The Royal College of Ophthalmologists and Clinical Council for Eye Health Commissioning. Commissioning Quide: Adult Cataract Surgery; The Royal College of Ophthalmologists and Clinical Council for Eye Health Commissioning: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Vist, G.E.; Kunz, R.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Schunemann, H.J. GRADE: An emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008, 336, 924–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- American Academy of Ophthalmology. Cataract in the Adult Eye Preferred Practice Pattern; American Academy of Ophthalmology: Chicago, IL, USA, 2011; Available online: http://bdoc.info/dl/informationen/Cataract-in-the-Adult-Eye-2011-AAO-komplett.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Canadian Ophthalmological Society Cataract Surgery Clinical Practice Guideline Expert C. Canadian Ophthalmological Society evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for cataract surgery in the adult eye. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2008, 43 (Suppl. S1), S7–S57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Royal College of Ophthalmologists. Cataract Surgery Guidelines; The Royal College of Ophthalmologists: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Malvankar-Mehta, M.S.; Chen, Y.N.; Patel, S.; Leung, A.P.; Merchea, M.M.; Hodge, W.G. Immediate versus Delayed Sequential Bilateral Cataract Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0131857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yoshizaki, M.; Ramke, J.; Zhang, J.H.; Aghaji, A.; Furtado, J.M.; Burn, H.; Gichuhi, S.; Dean, W.H.; Congdon, N.; Burton, M.J.; et al. How can we improve the quality of cataract services for all? A global scoping review. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2021, 49, 672–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Balasingam, B.; Mills, E.C.; Zarei-Ghanavati, M.; Liu, C. A survey exploring ophthalmologists’ attitudes and beliefs in performing Immediately Sequential Bilateral Cataract Surgery in the United Kingdom. BMC Ophthalmol. 2020, 20, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzybowski, A.; Wasinska-Borowiec, W.; Claoue, C. Pros and cons of immediately sequential bilateral cataract surgery (ISBCS). Saudi J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 30, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dickman, M.M.; Spekreijse, L.S.; Winkens, B.; Schouten, J.S.A.G.; Simons, R.W.P.; Dirksen, C.D. Immediate sequential bilateral surgery versus delayed sequential bilateral surgery for cataracts (protocol). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, CD013270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, M.J.; Ramke, J.; Marques, A.P.; Bourne, R.R.A.; Congdon, N.; Jones, I.; Ah Tong, B.A.M.; Arunga, S.; Bachani, D.; Bascaran, C.; et al. The Lancet Global Health Commission on Global Eye Health: Vision beyond 2020. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e489–e551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health British Columbia. Cataract—Treatment of Adults; Ministry of Health British Columbia: Victoria, BC, USA, 2021.

- Miller, K.M.; Oetting, T.A.; Tweeten, J.P.; Carter, K.; Lee, B.S.; Lin, S.; Nanji, A.A.; Shorstein, N.H.; Musch, D.C.; American Academy of Ophthalmology Preferred Practice Pattern Cataract/Anterior Segment P. Cataract in the Adult Eye Preferred Practice Pattern. Ophthalmology 2022, 129, P1–P126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucinotta, D.; Vanelli, M. WHO Declares COVID-19 a Pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020, 91, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- VISION 2020: The Right to Sight—INDIA. Management of Cataract in India. 2020. Available online: https://www.vision2020india.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/cataract-manual-vision2020.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Developing NICE Guidelines: The Manual; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Annex B: Key to Evidence Statements and Grades of Recommendations. In SIGN 50: A Guideline Developer’s Handbook, 2008 ed.; Revised 2011; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network: Edinburgh, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

| Title and Abstract Screening | Full Text Screening | Quality Appraisal * |

|---|---|---|

| (1) The identified report was not a CPG (2) The guideline was published before 2010 (3) The guideline was not in English (4) The guideline was not developed for cataract | (1) There was commercial funding or unmanaged conflicts of interest (2) Absence of affiliation of authors | (1) The average score of the two investigators for items 4, 7, 8, 12, or 22 was below 3. (2) the sum of the average score of the two investigators was less than 45 for items 4, 7, 8, 10, 12, 13, 15, 22, and 23. |

| AGREE II Item Number | Item Description |

|---|---|

| 4 | The guideline development group includes individuals from all relevant professional groups * |

| 7 | Systematic methods were used to search for evidence. |

| 8 | The criteria for selecting the evidence are clearly described. |

| 10 | The methods for formulating the recommendations are clearly described. |

| 12 | There is an explicit link between the recommendations and the supporting evidence. |

| 13 | The guideline has been externally reviewed by experts prior to its publication. |

| 15 | The recommendations are specific and unambiguous. |

| 22 | The views of the funding body have not influenced the content of the guideline. |

| 23 | Competing interests of guideline development group members have been recorded and addressed. |

| Clinical Practice Guideline (CPG) | Average AGREE II Scores | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item Number(s) | ||||||

| 4 | 7 | 8 | 12 | 22 | 4, 7, 8, 10, 12, 13, 15, 22, 23 | |

| CPGs selected for inclusion after appraisal | ||||||

| National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2017, Cataracts in adults; management [14] | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 53.5 |

| American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2016, Cataract in the Adult Eye Preferred Practice Pattern [15] | 5 | 6.5 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 49.5 |

| Rajavi et al., 2015, Customized clinical practice guidelines for management of adult cataract in Iran [16] | 5 | 3 | 4 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 49.5 |

| The Royal College of Ophthalmologists and Clinical Council for Eye Health Commissioning, 2018, Commissioning guide: Adult cataract surgery [17] | 7 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4.5 | 45 |

| CPGs excluded after appraisal | ||||||

| The Royal College of Ophthalmologists and the Royal College of Anaesthetists, 2012, Local Anaesthesia for Ophthalmic Surgery | 6.5 | 3 | 5 | 3.5 | 1 | 29.5 |

| The Royal College of Ophthalmologists, 2018, Ophthalmic Services Guidance: Theatre Procedures | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 15.5 |

| The Royal College of Ophthalmologists, 2016, Ophthalmic Services Guidance: Managing an outbreak of postoperative endophthalmitis | 2.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 14.5 |

| The Royal College of Ophthalmologists, 2018, Ophthalmic Services Guidance: Theatre facilities and equipment | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 14.5 |

| The Royal College of Ophthalmologists and the UK Ophthalmology Alliance, 2018, Quality Standard: Correct IOL implantation in cataract surgery | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 12 |

| Clinical Practice Guideline | Quality of Evidence, n (%) * | Strength of Recommendation, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High/Good | Moderate | Low/Insufficient | Strong | Discretionary | |

| CPG 1: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2017, Cataracts in adults; management [14] ** | 6 (27) | 5 (23) | 11 (50) | 36 (75) | 12 (25) |

| CPG 2: American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2016, Cataract in the Adult Eye Preferred Practice Pattern [15]. | 64 (86) | 8 (11) | 2 (3) | 72 (97) | 2 (3) |

| CPG 3: Rajavi et al., 2015, Customized clinical practice guidelines for management of adult cataract in Iran [16] *** | I: 31 (38) | II: 11 (14) | III–IV: 39 (48) | - | - |

| CPG 4: The Royal College of Ophthalmologists and Clinical Council for Eye Health Commissioning, 2018, Commissioning guide: Adult cataract surgery [17] *** | - | - | - | - | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, J.H.; Ramke, J.; Lee, C.N.; Gordon, I.; Safi, S.; Lingham, G.; Evans, J.R.; Keel, S. A Systematic Review of Clinical Practice Guidelines for Cataract: Evidence to Support the Development of the WHO Package of Eye Care Interventions. Vision 2022, 6, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision6020036

Zhang JH, Ramke J, Lee CN, Gordon I, Safi S, Lingham G, Evans JR, Keel S. A Systematic Review of Clinical Practice Guidelines for Cataract: Evidence to Support the Development of the WHO Package of Eye Care Interventions. Vision. 2022; 6(2):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision6020036

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Justine H., Jacqueline Ramke, Chan Ning Lee, Iris Gordon, Sare Safi, Gareth Lingham, Jennifer R. Evans, and Stuart Keel. 2022. "A Systematic Review of Clinical Practice Guidelines for Cataract: Evidence to Support the Development of the WHO Package of Eye Care Interventions" Vision 6, no. 2: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision6020036

APA StyleZhang, J. H., Ramke, J., Lee, C. N., Gordon, I., Safi, S., Lingham, G., Evans, J. R., & Keel, S. (2022). A Systematic Review of Clinical Practice Guidelines for Cataract: Evidence to Support the Development of the WHO Package of Eye Care Interventions. Vision, 6(2), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision6020036