Contextual Effects in Face Lightness Perception Are Not Expertise-Dependent

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

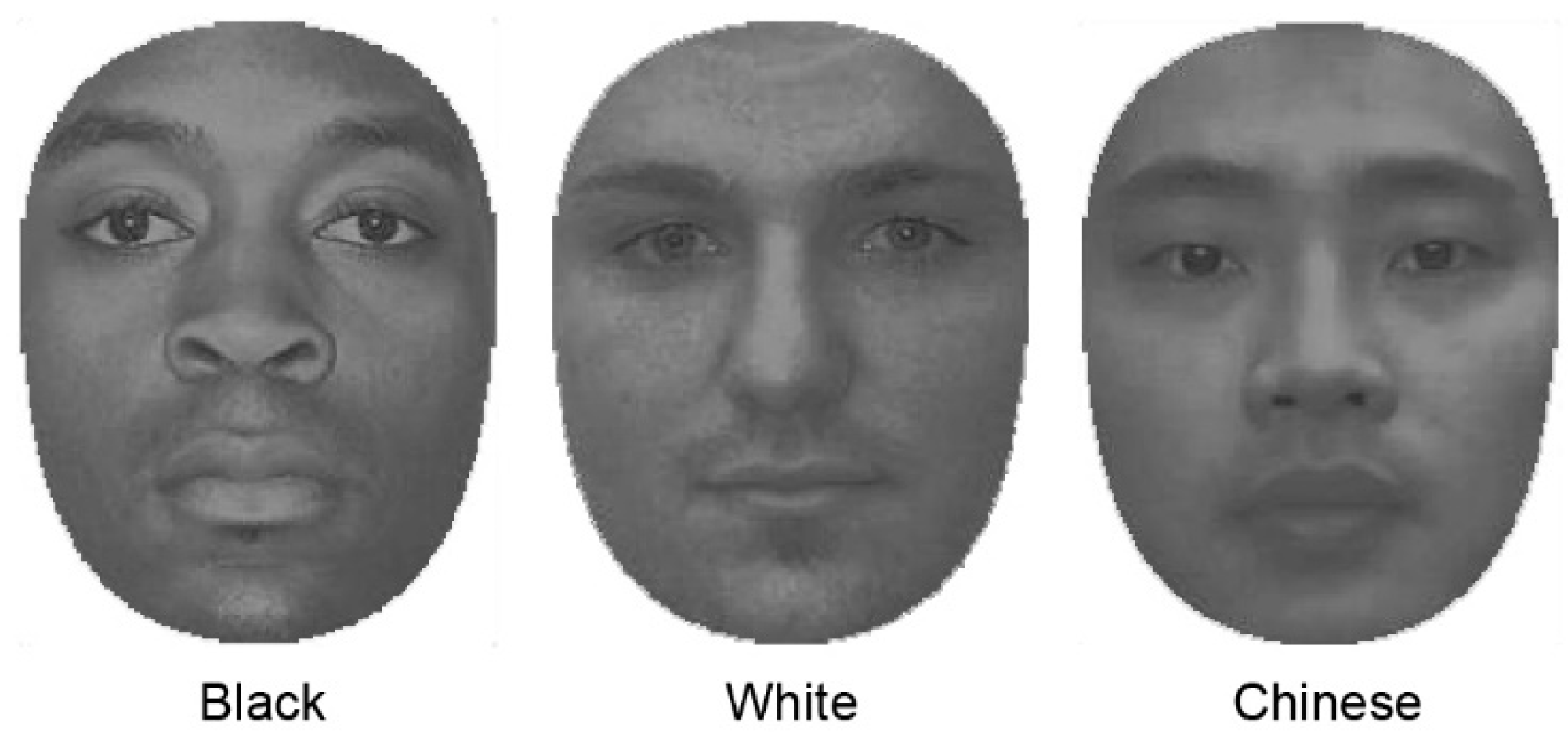

2.2. Stimuli and Apparatus

2.3. Tasks and Procedures

3. Results

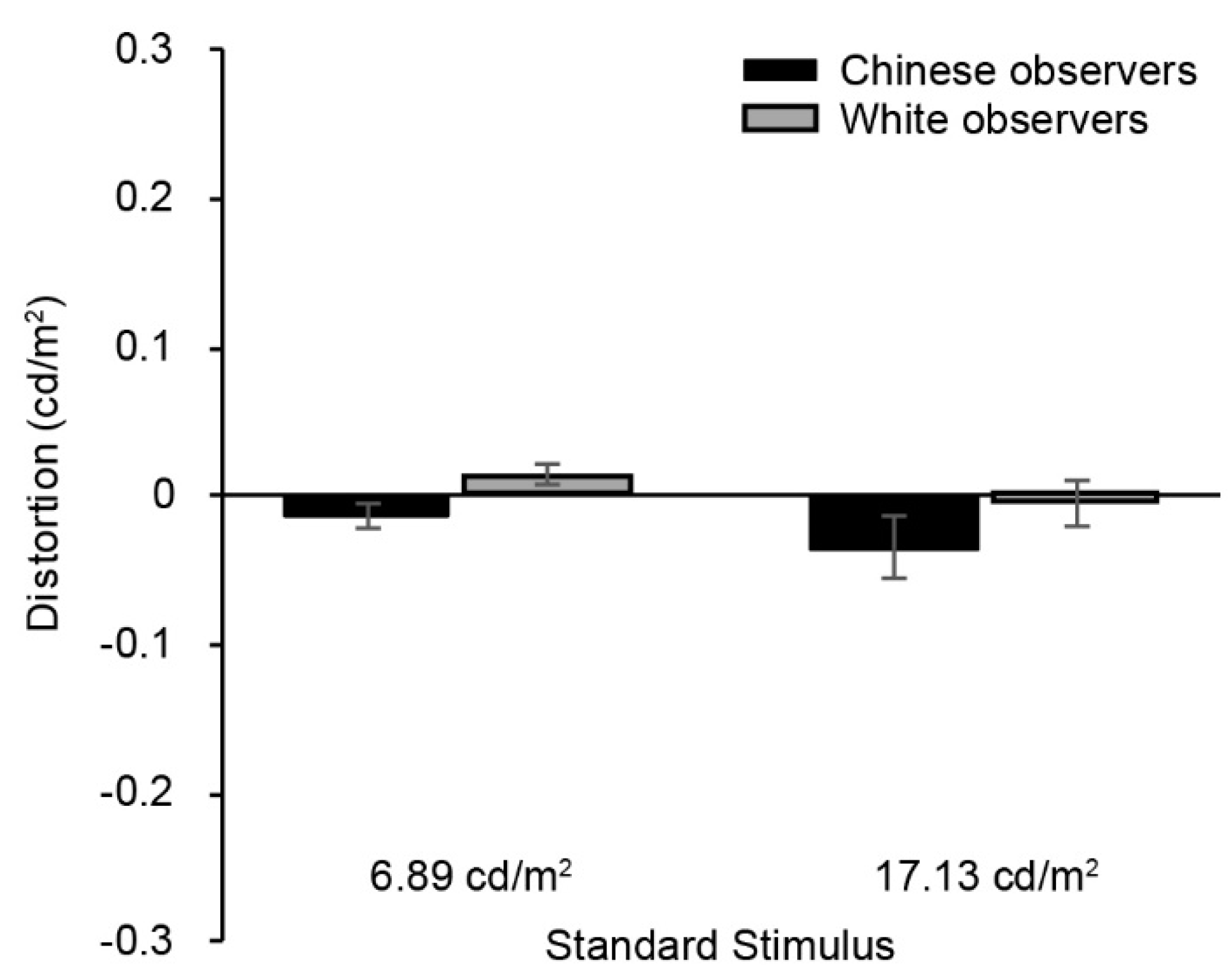

3.1. Face Matches

3.2. Patch Matches

3.3. Matching Durations

3.4. Race Recognition

4. Discussion

4.1. The Effect of Race Context on Face Lightness Judgments

4.2. The (Lack of) Expertise-Related Modulations in Face Lightness Estimations

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gibson, J.J.; Radner, M. Adaptation, after-effect and contrast in the perception of tilted lines. I. Quantitative studies. J. Exp. Psychol. 1937, 20, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, C.W.G. The tilt illusion: Phenomenology and functional implications. Vis. Res. 2014, 104, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, T.W.; Westheimer, G. Interference with stereoscopic acuity: Spatial, temporal, and disparity tuning. Vis. Res. 1978, 18, 1387–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badcock, D.R.; Westheimer, G. Spatial location and hyperacuity: The centre/surround localization contribution function has two substrates. Vis. Res. 1985, 25, 1259–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratliff, F. Mach Bands: Quantitative Studies on Neural Networks; Holden-Day: San Francisco, CA, USA; London, UK; Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Ejima, Y.; Takahashi, S. Apparent contrast of a sinusoidal grating in the simultaneous presence of peripheral gratings. Vis. Res. 1985, 25, 1223–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, M.W.; Fullenkamp, S.C. Spatial interactions in apparent contrast: Inhibitory effects among grating patterns of different spatial frequencies, spatial positions and orientations. Vis. Res. 1991, 31, 1985–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelson, E.H. Perceptual organization and the judgment of brightness. Science 1993, 262, 2042–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, C.D.; Wiesel, T.N. The influence of contextual stimuli on the orientation selectivity of cells in primary visual cortex of the cat. Vis. Res. 1990, 30, 1689–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillito, A.; Jones, H. Context-dependent interactions and visual processing in V1. J. Physiol. Paris 1996, 90, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeren, H.K.M.; van Heijnsbergen, C.C.R.J.; de Gelder, B. Rapid perceptual integration of facial expression and emotional body language. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 16518–16523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Van den Stock, J.; Righart, R.; De Gelder, B. Body expressions influence recognition of emotions in the face and voice. Emotion 2007, 7, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massaro, D.W.; Egan, P.B. Perceiving affect from the voice and the face. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 1996, 3, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dolan, R.J.; Morris, J.S.; de Gelder, B. Crossmodal binding of fear in voice and face. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 10006–10010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Righart, R.; De Gelder, B. Context influences early perceptual analysis of faces—An electrophysiological study. Cereb. Cortex 2005, 16, 1249–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, T.; Olkkonen, M.; Walter, S.; Gegenfurtner, K.R. Memory modulates color appearance. Nat. Neurosci. 2006, 9, 1367–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olkkonen, M.; Hansen, T.; Gegenfurtner, K.R. Color appearance of familiar objects: Effects of object shape, texture, and illumination changes. J. Vis. 2008, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aviezer, H.; Hassin, R.R.; Ryan, J.; Grady, C.; Susskind, J.; Anderson, A.; Moscovitch, M.; Bentin, S. Angry, disgusted, or afraid? Studies on the malleability of emotion perception. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 19, 724–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Changizi, M.A.; Zhang, Q.; Shimojo, S. Bare skin, blood and the evolution of primate colour vision. Biol. Lett. 2006, 2, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jablonski, N.G.; Chaplin, G. The evolution of human skin coloration. J. Hum. Evol. 2000, 39, 57–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adelson, E.H. Lightness Perception and Lightness Illusions. In The New Cognitive Neurosciences, 2nd ed.; Gazzaniga, M., Ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000; pp. 339–351. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Matsushita, S.; Morikawa, K. Effects of Lip Color on Perceived Lightness of Human Facial Skin. Iperception 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- MacLin, O.H.; Malpass, R.S. Racial categorization of faces: The ambiguous race face effect. Psychol. Public Policy Law 2001, 7, 98–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLin, O.H.; Malpass, R.S. The ambiguous-race face illusion. Perception 2003, 32, 249–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, D.T.; Banaji, M.R. Distortions in the perceived lightness of faces: The role of race categories. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2006, 135, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firestone, C.; Scholl, B.J. “Top-down” effects where none should be found: The El Greco fallacy in perception research. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 25, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrick, C.B.; Taylor, D.; Correa, E.I. Color sensitivity and mood disorders: Biology or metaphor? J. Affect. Disord. 2002, 68, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radel, R.; Clément-Guillotin, C. Evidence of motivational influences in early visual perception: Hunger modulates conscious access. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 23, 232–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, P.; Chatterjee, P.; Sinha, J. Is it light or dark? Recalling moral behavior changes perception of brightness. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 23, 407–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhalla, M.; Proffitt, D.R. Visual–motor recalibration in geographical slant perception. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 1999, 25, 1076–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firestone, C.; Scholl, B.J. Can you experience ‘top-down’effects on perception?: The case of race categories and perceived lightness. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2015, 22, 694–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, L.J.; Levin, D.T. The Face-Race Lightness Illusion Is Not Driven by Low-level Stimulus Properties: An Empirical Reply to Firestone and Scholl (2014). Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2016, 23, 1989–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Willenbockel, V.; Fiset, D.; Tanaka, J.W. Relative influences of lightness and facial morphology on perceived race. Perception 2011, 40, 621–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, K.R.; Gwinn, O.S. No role for lightness in the perception of black and white? Simultaneous contrast affects perceived skin tone, but not perceived race. Perception 2010, 39, 1142–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gwinn, O.S.; Brooks, K.R. No role for lightness in the encoding of Black and White: Race-contingent face aftereffects depend on facial morphology, not facial luminance. Vis. Cogn. 2015, 23, 597–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, H.; Bruce, V.; Akamatsu, S. Perceiving the sex and race of faces: The role of shape and colour. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 1995, 261, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.-M.; Balas, B. The influence of flankers on race categorization of faces. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 2012, 74, 1654–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dunham, Y.; Stepanova, E.V.; Dotsch, R.; Todorov, A. The development of race-based perceptual categorization: Skin color dominates early category judgments. Dev. Sci. 2015, 18, 469–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunham, Y.; Dotsch, R.; Clark, A.R.; Stepanova, E.V. The development of White-Asian categorization: Contributions from skin color and other physiognomic cues. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0158211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, D.T. Race as a visual feature: Using visual search and perceptual discrimination tasks to understand face categories and the cross-race recognition deficit. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2000, 129, 559–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, J.W.; Kiefer, M.; Bukach, C.M. A holistic account of the own-race effect in face recognition: Evidence from a cross-cultural study. Cognition 2004, 93, B1–B9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feingold, G.A. Influence of environment on identification of persons and things. J. Am. Inst. Crim. Criminol. 1914, 5, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malpass, R.S.; Kravitz, J. Recognition for faces of own and other race. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1969, 13, 330–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, W.-J.; Lindsay, R.C. Cross-race facial recognition: Failure of the contact hypothesis. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1994, 25, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, T. Upside-down faces: A review of the effect of inversion upon face recognition. Br. J. Psychol. 1988, 79, 471–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentine, T.; Endo, M. Towards an exemplar model of face processing: The effects of race and distinctiveness. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. Sect. A 1992, 44, 671–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Cao, B.; Shan, S.; Chen, X.; Zhou, D.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, D. The CAS-PEAL large-scale Chinese face database and baseline evaluations. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Part A Syst. Hum. 2008, 38, 149–161. [Google Scholar]

- Minear, M.; Park, D.C. A lifespan database of adult facial stimuli. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 630–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brainard, D.H.; Vision, S. The psychophysics toolbox. Spat. Vis. 1997, 10, 433–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelli, D.G. The VideoToolbox software for visual psychophysics: Transforming numbers into movies. Spat. Vis. 1997, 10, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, G.; Brake, S.; Taylor, K.; Tan, S. Expertise and configural coding in face recognition. Br. J. Psychol. 1989, 80, 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, M.E. Race of the interviewer and perception of skin color: Evidence from the multi-city study of urban inequality. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2002, 67, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, D.J.; Liu, S.; Lee, K.; Quinn, P.C.; Pascalis, O.; Slater, A.M.; Ge, L. Development of the other-race effect during infancy: Evidence toward universality? J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2009, 104, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kelly, D.J.; Quinn, P.C.; Slater, A.M.; Lee, K.; Ge, L.; Pascalis, O. The other-race effect develops during infancy: Evidence of perceptual narrowing. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 18, 1084–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heron-Delaney, M.; Anzures, G.; Herbert, J.S.; Quinn, P.C.; Slater, A.M.; Tanaka, J.W.; Lee, K.; Pascalis, O. Perceptual training prevents the emergence of the other race effect during infancy. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeimbekis, J.; Raftopoulos, A. The Cognitive Penetrability of Perception: New Philosophical Perspectives; OUP: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler, H.; Phillips, J.P.; Bruce, V.; Soulie, F.F.; Huang, T.S. Face Recognition: From Theory to Applications; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2012; Volume 163. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chang, D.H.F.; Cheang, Y.Y.; So, M. Contextual Effects in Face Lightness Perception Are Not Expertise-Dependent. Vision 2018, 2, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision2020023

Chang DHF, Cheang YY, So M. Contextual Effects in Face Lightness Perception Are Not Expertise-Dependent. Vision. 2018; 2(2):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision2020023

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Dorita H. F., Yin Yan Cheang, and May So. 2018. "Contextual Effects in Face Lightness Perception Are Not Expertise-Dependent" Vision 2, no. 2: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision2020023

APA StyleChang, D. H. F., Cheang, Y. Y., & So, M. (2018). Contextual Effects in Face Lightness Perception Are Not Expertise-Dependent. Vision, 2(2), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision2020023