Indirect Structural Muscle Injuries of Lower Limb: Rehabilitation and Therapeutic Exercise

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Muscle Injuries Rehabilitation

- Muscle ultrasound allows to detect the structural damage of the skeletal muscle after 36–48 h from injury, because the hemorrhagic collection is maximized after 24 h and decreases after 48 h [9].

- In the immediate post injury period (24–72 h) it is advisable to apply the PRICE (Protection, Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation) principle [27]. It is widely used, although there are no high quality randomized clinical trials to prove its effectiveness [28,29,30]. In clinical practice, immediate compression with 15 min cryotherapy cycles, with ice-free phases between, is recommended. Compressive cryotherapy (CC) [31], namely the association between cryotherapy and the application of pressure, deserves separate consideration: CC duration should be 15–20 min, repeated at intervals of 30–60 min for a total of 6 h, so as to substantially limit both the hemorrhage and the myofibril necrosis at the site of injury [32]. It is advisable to apply a compressive bandage and/or compressive cryotherapy within the range of 40–50 mmHg [23].

- A short rest period and/or relative immobilization immediately after the injury is recommended. This rest period optimizes the formation of connective tissue by fibroblasts, thereby reducing the risk of recurrences. Usually crutches are not necessary, while taping can be useful both for immobilization and liquid drainage. However, rest and immobilization should be reduced to only the first postlesion days (3–5 days) [10,14,22,28]. It would be better to have a short immobilization period followed by a progressive load able to favor the correct progression of healing process (POLICE: Protection, Optimal Loading, Ice, Compression, Elevation) [9].

- After the first 24 h postlesion, it is a good idea to start performing complete lymphatic draining massages and to replace the compression bandage with an elastic bandage [9].

- Functional goals [9]: treatment of predisposing factors and antagonist muscles; pain-free activity of daily life; pain-free strength training of the injured muscle, at least 50% of theoretical maximum load; recovery of at least 90% of the extensibility deficit of the injured muscle.

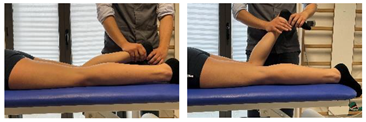

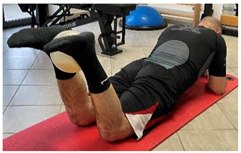

- Figure: physician and physiotherapist.

- Location: gym.

- Red Flags [9]: presence of pain when performing strength exercises or low-speed running on the treadmill.

- Image criteria: US check on the 2nd and 4th−5th day after injury [9].

- The type of contraction recommended in this first phase is an isometric modality. In fact, during the isometric contraction, there is no myofilaments slippage and, therefore, there is no macro change of the muscle length [22,40]. Between 30 and 50 repetitions of 10–20 s of contraction under the threshold of pain are suggested. According to biomechanics concepts, the internal torque varies along the range of movement (ROM) of each joint. Each joint has specific degrees within the ROM in which the muscle is able to generate the maximum internal force and the anatomical position of muscle–tendon–bone unit give a maximum internal moment arm, generating the maximum torque. To gradually increase mechanical stress on the damaged muscle, it is necessary to proceed along the ROM gradually, by proposing contraction in ROM position where internal force is not able to produce the highest tension of the muscle.

- It is important to correctly perform exercises to recover the extensibility of injured muscle (passive, assisted/active, static or dynamic) [9], and better if with functional schemes. All exercises must be under the threshold of pain. An increased joint range was verified for stretches performed following functional patterns. In case of bi-articular muscles, it is advisable to stretch both insertional areas [41,42].

- Deep massages on the affected area should be avoided [10].

- Elastic bandage is continued until there is liquid collection.

- If there is an excessive hematoma formation within the injured area, it is advisable to proceed to an echo-guided aspiration before the hematoma organization [43].

- It is useful to start an aerobic workout as soon as possible, using non-injured muscles (i.e., upper trunk aerobic workout) [9].

- At the end of each working session, ice massage should be performed for 15–20 min [9].

- The use of electrical stimulation should be encouraged from the first postlesion days to the end of the regeneration phase (up to about the third postlesion week) [10,44,45,46]. Transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation (TENS) is the form of electrical stimulation most recommended in its two forms: conventional and acupuncture-like; several trials highlight its potential role in inhibition of transmission of pain signals [44]. Neuromuscular electrostimulation (NMES) utilizes high-intensity electrical stimulation to elicit intermittent contraction and relaxation of proximal muscle fibers; it is widely prescribed for physical rehabilitation and muscle strengthening [44]. It has been demonstrated that these two techniques can stimulate the implantation of muscle resident stem cells inside the injured area, along with the voluntary exercise performed during rehabilitation [47,48,49].

- Many studies have shown that LT can reduce the inflammatory process of the damaged muscle tissue [52], speed up the tissue regeneration [53], optimize the oxidative metabolism [54] and stimulate cell proliferation [55,56]. Therefore, the use of LT appears to be justified by sufficient evidence, even if not high quality featured [9,10,57].

- Hyperthermia therapy (HT) has proven to be able to stimulate the tissue repair processes, diminish pain symptoms, increase tissue flexibility, and reduce muscular and joint stiffness [58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66]. However, there are poor specific evidence on the HT effectiveness in muscular injuries [9,10].

- Analgesic (paracetamol) can be used in case of pain in the first postlesion days [9,10,67,68], while muscle relaxants, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections require further evidence-based studies to evaluate their effectiveness [23,69]. The use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is controversial [70], and it is not recommended.

- Functional goals [9]: absence of pain or feeling of diversity in injured muscle when performing exercises; complete recovery of the extensibility of the injured muscle; recovery of the aerobic sport-specific parameters; complete recovery of the pre-injury weight.

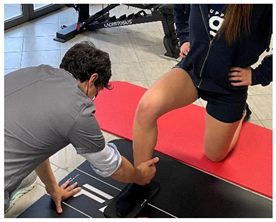

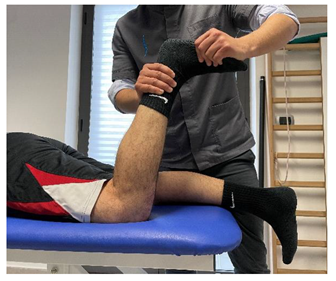

- Figure: physiotherapist and athletic trainer.

- Location: gym and sport-field.

- Clinic criteria [10,23,71]: resolution of swelling, if initially present; absence of pain in response to maximal isometric contraction; absence of pain in response to end-range stretching tests carried out in the active and passive modes; complete range of motion (ROM) of the joints involved in the movement.

- Imaging criteria [10,72,73]: resolution of the lesion gap as observed with US or MRI imaging; the presence of granulation repair tissue within the cicatrix zone (CZ) as revealed by the US. US findings observed during normal healing depend on the nature of the original injury and initial sonographic findings. Minor lesions may increase in echogenicity during the healing process. In these cases, a progressive reduction in intensity or its disappearance is considered normal. More prominent lesions may present as hypoechogenic regions with adjacent fluid collection. Resolution or substantial decrease in the quantity of fluid is to be expected during the normal healing process [74,75].

- Red Flags [9]: extensibility test still positive.

- There is the introduction of progressively intense concentric exercises. During a concentric contraction, the bulk of the muscle shortens due to the sliding motion of the myofilaments with a relatively constant force proportional to the external load, so the CZ is not subjected to traction and the jagged muscle edges, avoiding diastasis [79]. The concentric contraction should be slow and controlled; they can be manual at the beginning, and subsequently with isotonic equipment [80]. Sixty percent of one repetition maximum (RM) should not be exceeded when performing these exercises in this stage [79,80]. The eccentric phase of the movement must, in all cases, be reduced to the minimum possible intensity [10].

- Keep performing exercises to recover the extensibility of injured muscle [9].

- The practice of massage can be introduced as the completion of tissue healing processes has started [10].

- Physical therapies started could be continued in this phase.

- Functional goals [9]: consolidation of the strength and extensibility characteristics of the injured muscle; recovery of the sport-specific skills; recovery of the high-intensity sport-specific athletic parameters; working resistance of the injured muscle.

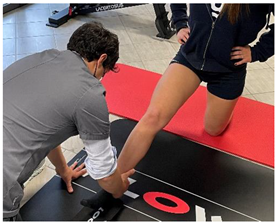

- Figure: physiotherapist and athletic trainer.

- Location: gym and sport-field.

- Imaging criteria [10,72,73]: substantial disappearance of the lesion gap on US or MRI examination; presence of compact granulation repair tissue as revealed by US or MRI. Over time small tears may fill with echogenic material, likely representing scar tissue visible at US [84,85]. More extensive scarring results in increased likelihood of recurrent injury [25].

- Red Flags [9]: “different” muscle feeling during or after training.

- Exercises predominantly based on eccentric contractions of progressively increasing intensity [9,10,23,86,87,88] could be started after an effective concentric contraction is reached. These should be muscle and location specified [89]. These can be performed even with the use of elastic resistance bandages, where the intensity of the eccentric phase is progressively increased [10,23]. Even if some authors suggest introducing eccentric exercises as soon as possible in the rehabilitation protocol [9], the 3rd phase should be the preferred one for their execution. Moreover, evidence about isoinertial exercises are increasing [90].

- Stretching must be introduced gradually and exercises must not cause the onset of pain. The time of elongation initially is 10–15 s and subsequently up to 1 min, in order to induce a durable, and not just a transient, plastic deformation within the area of structural reorganization [10,23]. For bi-articular muscles, please consider both origin and insertion tendons.

3. Specific Exercise Rehabilitation

| Name | Image | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Isometric exercises | ||

| (In case of proximal hamstring lesion) |  | [23] |

| (In case of medial or distal hamstring lesion) |  | [23] |

| Isometric exercise at different angles |  | [23] |

| Dynamic exercises | ||

| The extender |  | [88,97] |

| The glider |  | [88,97] |

| Nordic hamstrings |   | [97] |

| Proprioceptive, neuromuscular and stretching exercises | ||

| Pendulum |  | [97] |

| Stretching Single Leg Raises |  | [97] |

| Secondary prevention exercises | ||

| Eccentric knee flexor stretch |   | [98] |

| Eccentric hip extensor stretch |  | [98] |

| Name | Image | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Isometric exercises | ||

| (In case of proximal lesion) |  | [23] |

| (In case of medial or distal lesion) |  | [23] |

| Dynamic exercises | ||

| (In case of proximal lesion) |  | [23] |

| (In case of medial or distal lesion) |  | [23] |

| Secondary prevention exercises | ||

| Eccentric hip flexor and knee extensor stretch (eccentric load to rectus femoris) |  | [98] |

| Name | Image | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Isometric exercises | ||

| Isometric exercise with ball |   | [23] |

| Dynamic exercises | ||

| Manual resisted adduction |  | [23] |

| Adduction with elastic resistance |  | [23] |

| Proprioceptive, neuromuscular, and stretching exercises | ||

| [23] | |

| Secondary prevention exercises | ||

| Eccentric side lunge stretch |   | [98] |

| Copenhagen adductor prevention programs |  | [99] |

| Name | Image | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Isometric exercises | ||

| Isometric contraction with manual resistance |   | [23] |

| Dynamic exercises | ||

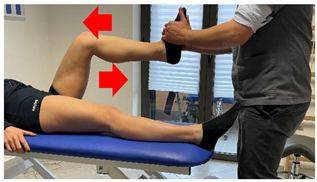

| Concentric/eccentric contraction with manual resistance |  | [23] |

| Concentric/eccentric heel raise |  | [23] |

| Proprioceptive, neuromuscular, and stretching exercises | ||

| [23] | |

4. Return to Training (RTT) and Return to Play (RTP)

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alonso, J.M.; Edouard, P.; Fischetto, G.; Adams, B.; Depiesse, F.; Mountjoy, M. Determination of future prevention strategies in elite track and field: Analysis of Daegu 2011 IAAF Championships injuries and illnesses surveillance. Br. J. Sports Med. 2012, 46, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freckleton, G.; Pizzari, T. Risk factors for hamstring muscle strain injury in sport: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2013, 47, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, N.; James, S.L.J.; Lee, J.C.; Chakraverty, R. British athletics muscle injury classification: A new grading system. Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 1347–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallén, A.; Ekstrand, J. Return to play following muscle injuries in professional footballers. J. Sports Sci. 2014, 32, 1229–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldén, M.; Hägglund, M.; Bengtsson, H.; Ekstrand, J. Perspectives in football medicine. Unfallchirurg 2018, 121, 470–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekstrand, J.; Hägglund, M.; Waldén, M. Epidemiology of muscle injuries in professional football (soccer). Am. J. Sports Med. 2011, 39, 1226–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hägglund, M.; Waldén, M.; Ekstrand, J. Risk factors for lower extremity muscle injury in professional soccer: The UEFA Injury Study. Am. J. Sports Med. 2013, 41, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maffulli, N.; Oliva, F.; Frizziero, A.; Nanni, G.; Barazzuol, M.; Giai Via, A.; Ramponi, C.; Brancaccio, P.; Listano, G.; Rizzo, D.; et al. ISMuLT Guidelines for muscle injuries. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2013, 3, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanni, G.; Frizziero, A.; Oliva, F.; Maffulli, N. Gli Infortuni Muscolari-Linee Guida, I.S.Mu.L.T; Calzetti Mariucci Editore: Torgiano, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bisciotti, G.N.; Volpi, P.; Amato, M.; Alberti, G.; Allegra, F.; Aprato, A.; Artina, M.; Auci, A.; Bait, C.; Bastieri, G.M.; et al. Italian consensus conference on guidelines for conservative treatment on lower limb muscle injuries in athlete. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2018, 4, e000323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diagnostik und Therapie von Zerrungen und Muskelfaserrissen im Hochleistungssport. In Manual des Deutschen Fußball-Bundes (DFB); Müller-Wohlfahrt, H.W., Ed.; Deutscher Fußball-Bundes: Frankfurt, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tol, J.L.; Hamilton, B.; Best, T.M. Palpating muscles, massaging the evidence? An editorial relating to; Terminology and classification of muscle injuries in sport: The Munich consensus statement. Br. J. Sports Med. 2013, 47, 340–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotfiel, T.; Seil, R.; Bily, W.; Bloch, W.; Gokeler, A.; Krifter, R.M.; Mayer, F.; Ueblacker, P.; Weisskopf, L.; Engelhardt, M. Nonoperative treatment of muscle injuries-recommendations from the GOTS expert meeting. J. Exp. Orthop. 2018, 5, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Järvinen, T.A.; Järvinen, M.; Kalimo, H. Regeneration of injured skeletal muscle after the injury. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2013, 3, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maffulli, N.; Aicale, R.; Tarantino, D. Classification of Muscle Lesions. In Muscle and Tendon Injuries; Canata, G., d’Hooghe, P., Hunt, K., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller-Wohlfahrt, H.-W.; Haensel, L.; Mithoefer, K.; Ekstrand, J.; English, B.; McNally, S.; Orchard, J.; van Dijk, C.N.; Kerkhoffs, G.M.; Schamasch, P.; et al. Terminology and classification of muscle injuries in sport: The Munich consensus statement. Br. J. Sports Med. 2013, 47, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, O.; Del Buono, A.; Best, T.M.; Maffulli, N. Acute muscle strain injuries: A proposed new classification system. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2012, 20, 2356–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valle, X.; Alentorn-Geli, E.; Tol, J.L.; Hamilton, B.; Garrett, W.E., Jr.; Pruna, R.; Til, L.; Antoni Gutierrez, J.; Alomar, X.; Balius, R.; et al. Muscle Injuries in Sports: A New Evidence-Informed and Expert Consensus-Based Classification with Clinical Application. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 1241–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekstrand, J.; Askling, C.; Magnusson, H.; Mithoefer, K. Return to play after thigh muscle injury in elite football players: Implementation and validation of the Munich muscle injury classification. Br. J. Sports Med. 2013, 47, 769–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendiguchia, J.; Martinez-Ruiz, E.; Edouard, P.; Morin, J.B.; Martinez-Martinez, F.; Idoate, F.; Mendez-Villanueva, A. A Multifactorial, Criteria-based Progressive Algorithm for Hamstring Injury Treatment. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2017, 49, 1482–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.M.; Scott, A. Mechanotherapy: How physical therapists’ prescription of exercise promotes tissue repair. Br. J. Sports Med. 2009, 43, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järvinen, T.A.H.; Järvinen, T.L.N.; Kääriäinen, M.; Kalimo, H.; Järvinen, M. Muscle injuries: Biology and treatment. Am. J. Sports Med. 2005, 33, 745–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpi, P.; Bisciotti, G.N. Muscle Injury in the Athlete; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, V.; Spitz, R.W.; Bell, Z.W.; Viana, R.B.; Chatakondi, R.N.; Abe, T.; Loenneke, J.P. Exercise induced changes in echo intensity within the muscle: A brief review. J. Ultrasound. 2020, 23, 457–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappia, M.; Ascione, F.; Di Pietto, F.; Fischetti, M.; Romano, A.M.; Castagna, A.; Brunese, L. Long head biceps tendon instability: Diagnostic performance of known and new MRI diagnostic signs. Skelet. Radiol. 2021, 50, 1863–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappia, M.; Reginelli, A.; Chianca, V.; Carfora, M.; Di Pietto, F.; Iannella, G.; Mariani, P.P.; Di Salvatore, M.; Bartollino, S.; Maggialetti, N. MRI of popliteo-meniscal fasciculi of the knee: A pictorial review. Acta. Biomed. 2018, 19, 7–17. [Google Scholar]

- Bleakley, C.; McDonough, S.; MacAuley, D. The use of ice in the treatment of acute soft-tissue injury: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Sports Med. 2004, 32, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Järvinen, T.A.H.; Järvinen, T.L.N.; Kääriäinen, M.; Aärimaa, V.; Vaittinen, S.; Kalimo, H.; Järvinen, M. Muscle injuries: Optimising recovery. Best Pr. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2007, 21, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orchard, J.W.; Best, T.M.; Mueller-Wohlfahrt, H.-W.; Hunter, G.; Hamilton, B.H.; Webborn, N.; Jaques, R.; Kenneally, D.; Budgett, R.; Philips, N.; et al. The early management of muscle strains in the elite athlete: Best practice in a world with a limited evidence basis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2008, 42, 158–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleakley, C.M.; Glasgow, P.; MacAuley, D.C. PRICE needs updating, should we call the POLICE? Br. J. Sports Med. 2012, 46, 220–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, J.E. Cold and compression in the management of musculoskeletal injuries and orthopedic operative procedures: A narrative review. J. Sport Med. 2010, 1, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaser, K.-D.; Disch, A.C.; Stover, J.F.; Lauffer, A.; Bail, H.J.; Mittlmeier, T. Prolonged superficial local cryotherapy attenuates microcirculatory impairment, regional inflammation, and muscle necrosis after closed soft tissue injury in rats. Am. J. Sports Med. 2007, 35, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fyfe, J.J.; Opar, D.A.; Williams, M.D.; Shield, A.J. The role of neuromuscular inhibition in hamstring strain injury recurrence. J. Electromyogr Kinesiol. Off. J. Int Soc. Electrophys. Kinesiol. 2013, 23, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hägglund, M.; Waldén, M.; Ekstrand, J. Injury recurrence is lower at the highest professional football level than at national and amateur levels: Does sports medicine and sports physiotherapy deliver? Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.; Lee, S.; Kim, I.; Chung, M.; Kim, M.; Lim, H.; Park, J.; Kim, O.; Choi, H. The anti-inflammatory mechanism of 635 nm light-emitting-diode irradiation compared with existing COX inhibitors. Lasers Surg. Med. 2007, 39, 614–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, L.; Marcos, R.L.; Torres-Silva, R.; Pallota, R.C.; Magacho, T.; Mafra, F.P.F.; Macedo, M.M.; Carvalho, R.L.D.P.; Bjordal, J.M.; Lopes-Martins, R.A.B. Characterization of Skeletal Muscle Strain Lesion Induced by Stretching in Rats: Effects of Laser Photobiomodulation. Photomed Laser Surg. 2018, 36, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clijsen, R.; Brunner, A.; Barbero, M.; Clarys, P.; Taeymans, J. Effects of low-level laser therapy on pain in patients with musculoskeletal disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2017, 53, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, S.V. Current topics for teaching skeletal muscle physiology. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2003, 27, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delos, D.; Maak, T.G.; Rodeo, S.A. Muscle injuries in athletes: Enhancing recovery through scientific understanding and novel therapies. Sports Health 2013, 5, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias da Silva, S.R.; Gonçalves, M. Dynamic and isometric protocols of knee extension: Effect of fatigue on the EMG signal. Electromyogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2006, 46, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Decoster, L.C.; Cleland, J.; Altieri, C.; Russel, P. The effects of hamstring stretching on range of motion: A systematic literature review. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2005, 35, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasen, J.M.; O’Connor, A.M.; Schwartz, S.L.; Watson, J.O.; Plastaras, C.T.; Garvan, C.W.; Bulcao, C.; Johnson, S.C.; Akuthota, V. A randomized controlled trial of hamstring stretching: Comparison of four techniques. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2009, 23, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.O.; Hunt, N.J.; Wood, S.J. The physiotherapy management of muscle haematomas. Phys. Sport Off. J. Assoc. Chart. Physiother. Sport Med. 2006, 7, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.R.; Shurman, J. Combined neuromuscular electrical stimulation and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for treatment of chronic back pain: A double-blind, repeated measures comparison. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1997, 78, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero, A.J.; Wright, V.J.; Fu, F.H.; Huard, J. Stem cells for the treatment of skeletal muscle injury. Clin. Sports Med. 2009, 28, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Filippo, E.S.; Mancinelli, R.; Marrone, M.; Doria, C.; Verratti, V.; Toniolo, L.; Dantas, J.L.; Fulle, S.; Pietrangelo, T. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation improves skeletal muscle regeneration through satellite cell fusion with myofibers in healthy elderly subjects. J. Appl. Physiol. 2017, 123, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ljubicic, V.; Adhihetty, P.J.; Hood, D.A. Application of Animal Models: Chronic Electrical Stimulation-Induced Contractile Activity. Can. J. Appl. Physiol. 2005, 30, 625–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efthimiadou, A.; Asimakopoulos, B.; Nikolettos, N.; Giatromanolaki, A.; Sivridis, E.; Lialiaris, T.S.; Papachristou, D.N.; Kontoleon, E. The angiogenetic effect of intramuscular administration of b-FGF and a-FGF on cardiac muscle: The influence of exercise on muscle angiogenesis. J. Sports Sci. 2006, 24, 849–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellafiore, M.; Sivverini, G.; Palumbo, D.; Macaluso, F.; Bianco, A.; Palma, A.; Farina, F. Increased cx43 and angiogenesis in exercised mouse hearts. Int. J. Sports Med. 2007, 28, 749–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reher, P.; Doan, N.; Bradnock, B.; Meghji, S.; Harris, M. Effect of ultrasound on the production of IL-8, basic FGF and VEGF. Cytokine 1999, 11, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBrier, N.M.; Lekan, J.M.; Druhan, L.J.; Devor, S.T.; Merrick, M.A. Therapeutic ultrasound decreases mechano-growth factor messenger ribonucleic acid expression after muscle contusion injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2007, 88, 936–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adabbo, M.; Paolillo, F.R.; Bossini, P.S.; Rodrigues, N.C.; Bagnato, V.S.; Parizotto, N.A. Effects of Low-Level Laser Therapy Applied Before Treadmill Training on Recovery of Injured Skeletal Muscle in Wistar Rats. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2016, 34, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.N.; Fernandes, K.P.S.; Deana, A.M.; Bussadori, S.K.; Mesquita-Ferrari, R.A. Effects of low-level laser therapy on skeletal muscle repair: A systematic review. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2014, 93, 1073–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, D.; Greco, M.; Passarella, S. Specific helium-neon laser sensitivity of the purified cytochrome c oxidase. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2000, 76, 863–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renno, A.C.M.; McDonnell, P.A.; Parizotto, N.A.; Laakso, E.L. The effects of laser irradiation on osteoblast and osteosarcoma cell proliferation and differentiation in vitro. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2007, 25, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silveira, P.C.L.; da Silva, L.A.; Pinho, C.A.; De Souza, P.S.; Ronsani, M.M.; da Luz Scheffer, D.; Pinho, R.A. Effects of low-level laser therapy (GaAs) in an animal model of muscular damage induced by trauma. Lasers Med. Sci. 2013, 28, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Freitas, C.E.A.; Bertaglia, R.S.; Vechetti Júnior, I.J.; Mareco, E.A.; Salomão, R.A.; de Paula, T.G.; Nai, G.A.; Carvalho, R.F.; Pacagnelli, F.L.; Dal-Pai-Silva, M. High Final Energy of Low-Level Gallium Arsenide Laser Therapy Enhances Skeletal Muscle Recovery without a Positive Effect on Collagen Remodeling. Photochem. Photobiol. 2015, 91, 957–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giombini, A.; Casciello, G.; Di Cesare, M.C.; Di Cesare, A.; Dragoni, S.; Sorrenti, D. A controlled study on the effects of hyperthermia at 434 MHz and conventional ultrasound upon muscle injuries in sport. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 2001, 41, 521–527. [Google Scholar]

- Sorrenti, D.; Casciello, G.; Dragoni, S.; Giombini, A. Applicazione della termoterapia endogena nel trattamento delle lesioni muscolari da sport: Studio comparativo tra ipertermia e ultrasuoni. Med. Dello Sport 2000, 53, 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- Goats, G.C. Continuous short-wave (radio-frequency) diathermy. Br. J. Sports Med. 1989, 23, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, J.F.; Dundore, D.E.; Esselman, P.C.; Nelp, W.B. Microwave diathermy: Effects on experimental muscle hematoma resolution. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1983, 64, 127–129. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, J.F.; Brunner, G.D.; Mcmillan, J.A.; Silverman, D.R.; Johnston, V.C. Modification of Heating Patterns Produced by Microwaves at the Frequencies of 2456 and 900 mc. by Physiologic Factors in the Human. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1964, 45, 555–563. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, J.F.; Brunner, G.D.; Stow, R.W. Pain threshold measurements after therapeutic application of ultrasound, microwaves and infrared. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1958, 39, 560–565. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administration. Physical Medicine Devices; Reclassification of Shortwave Diathermy for All Other Uses, Henceforth To Be Known as Nonthermal Shortwave Therapy. Final order; technical correction. Fed. Regist. 2015, 80, 61298–61302. [Google Scholar]

- D’Agostino, M.C.; Craig, K.; Tibalt, E.; Respizzi, S. Shock wave as biological therapeutic tool: From mechanical stimulation to recovery and healing, through mechanotransduction. Int. J. Surg. 2015, 24, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGorm, H.; Roberts, L.A.; Coombes, J.S.; Peake, J.M. Turning Up the Heat: An Evaluation of the Evidence for Heating to Promote Exercise Recovery, Muscle Rehabilitation and Adaptation. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 1311–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Dalziel, S.R.; Lamdin, R.; Miles-Chan, J.L.; Frampton, C. Oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs versus other oral analgesic agents for acute soft tissue injury. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 7, CD007789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, A.L.; Rasmussen, L.K.; Kadi, F.; Schjerling, P.; Helmark, I.C.; Ponsot, E.; Aagaard, P.; Durigan, J.L.; Kjaer, M. Activation of satellite cells and the regeneration of human skeletal muscle are expedited by ingestion of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2016, 30, 2266–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamid, M.S.A.; Mohamed Ali, M.R.; Yusof, A.; George, J.; Lee, L.P. Platelet-rich plasma injections for the treatment of hamstring injuries: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Sports Med. 2014, 42, 2410–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almekinders, L.C. Anti-Inflammatory Treatment of Muscular Injuries in Sport. Sports Med. 1999, 28, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisciotti, G.N.; Eirale, C. Le lesioni muscolari indotte dall’esercizio: Il delayed muscle soreness. Med. Dello Sport 2012, 65, 423–435. [Google Scholar]

- Megliola, A.; Eutropi, F.; Scorzelli, A.; Gambacorta, D.; De Marchi, A.; De Filippo, M.; Faletti, C.; Ferrari, F.S. Ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging in sports-related muscle injuries. Radiol. Med. 2006, 111, 836–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandrino, F.; Balconi, G. Complications of muscle injuries. J. Ultrasound 2013, 16, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Takebayashi, S.; Takasawa, H.; Banzai, Y.; Miki, H.; Sasaki, R.; Itoh, Y.; Matsubara, S. Sonographic findings in muscle strain injury: Clinical and MR imaging correlation. J. Ultrasound Med. 1995, 14, 899–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guermazi, A.; Roemer, F.W.; Robinson, P.; Tol, J.L.; Regatte, R.R.; Crema, M.D. Imaging of Muscle Injuries in Sports Medicine: Sports Imaging Series. Radiology 2017, 282, 646–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laumonier, T.; Menetrey, J. Muscle injuries and strategies for improving their repair. J. Exp. Orthop. 2016, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, T.; English, A.W. Strategies to promote peripheral nerve regeneration: Electrical stimulation and/or exercise. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2016, 43, 336–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannus, P.; Parkkari, J.; Järvinen, T.L.N.; Järvinen, T.A.; Järvinen, M. Basic science and clinical studies coincide: Active treatment approach is needed after a sports injury. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2003, 13, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, S.; Morrissey, D.; Woledge, R.C.; Bader, D.L.; Screen, H.R. Eccentric and concentric loading of the triceps surae: An in vivo study of dynamic muscle and tendon biomechanical parameters. J. Appl. Biomech. 2015, 31, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaouachi, A.; Hammami, R.; Kaabi, S.; Chamari, K.; Drinkwater, E.J.; Behm, D.G. Olympic weightlifting and plyometric training with children provides similar or greater performance improvements than traditional resistance training. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2014, 28, 1483–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffa, S.; Perna, A.; Candela, G.; Cattolico, A.; Sellitto, C.; De Blasiis, P.; Guerra, G.; Tafuri, D.; Lucariello, A. Effects of Hoverboard on Balance in Young Soccer Athletes. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2020, 5, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherry, M.A.; Best, T.M. A comparison of 2 rehabilitation programs in the treatment of acute hamstring strains. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2004, 34, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliven, K.C.H.; Anderson, B.E. Core stability training for injury prevention. Sports Health 2013, 5, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, M.L.; Magnusson, S.P.; Kjaer, M. Early versus Delayed Rehabilitation after Acute Muscle Injury. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1300–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, J.; Thorborg, K.; Nielsen, M.B.; Skjødt, T.; Bolvig, L.; Bang, N.; Hölmich, P. The diagnostic and prognostic value of ultrasonography in soccer players with acute hamstring injuries. Am. J. Sports Med. 2014, 42, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendiguchia, J.; Alentorn-Geli, E.; Idoate, F.; Myer, G.D. Rectus femoris muscle injuries in football: A clinically relevant review of mechanisms of injury, risk factors and preventive strategies. Br. J. Sports Med. 2013, 47, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, T.F.; Schmitt, B.M.; Nicholas, S.J.; McHugh, M.P. Rehabilitation After Hamstring-Strain Injury Emphasizing Eccentric Strengthening at Long Muscle Lengths: Results of Long-Term Follow-Up. J. Sport Rehabil. 2017, 26, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askling, C.M.; Tengvar, M.; Thorstensson, A. Acute hamstring injuries in Swedish elite football: A prospective randomised controlled clinical trial comparing two rehabilitation protocols. Br. J. Sports Med. 2013, 47, 953–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishøi, L.; Sørensen, C.N.; Kaae, N.M.; Jørgensen, L.B.; Hölmich, P.; Serner, A. Large eccentric strength increase using the Copenhagen Adduction exercise in football: A randomized controlled trial. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2016, 26, 1334–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesch, P.A.; Fernandez-Gonzalo, R.; Lundberg, T.R. Clinical Applications of Iso-Inertial, Eccentric-Overload (YoYoTM) Resistance Exercise. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, J.; Hölmich, P. Evidence based prevention of hamstring injuries in sport. Br. J. Sports Med. 2005, 39, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanferdini, F.J.; Bini, R.R.; Baroni, B.M.; Klein, K.D.; Carpes, F.P.; Vaz, M.A. Improvement of Performance and Reduction of Fatigue with Low-Level Laser Therapy in Competitive Cyclists. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2018, 13, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, L.A.; Nosaka, K.; Coombes, J.S.; Peake, J.M. Cold water immersion enhances recovery of submaximal muscle function after resistance exercise. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2014, 307, R998–R1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieuzen, F.; Bleakley, C.M.; Costello, J.T. Contrast water therapy and exercise induced muscle damage: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62356. [Google Scholar]

- Duñabeitia, I.; Arrieta, H.; Torres-Unda, J.; Gil, J.; Santos-Concejero, J.; Gil, S.M.; Irazusta, J.; Bidaurrazaga-Letona, I. Effects of a capacitive-resistive electric transfer therapy on physiological and biomechanical parameters in recreational runners: A randomized controlled crossover trial. Phys. Ther. Sport Off. J. Assoc. Chart. Physiother. Sport Med. 2018, 32, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Bellmunt, A.; Casasayas, O.; Navarro, R.; Simon, M.; Martin, J.C.; Pérez-Corbella, C.; Blasi, M.; Ortiz, S.; Álvarez, P.; Pacheco, L. Effectiveness of low-frequency electrical stimulation in proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation techniques in healthy males: A randomized controlled trial. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 2019, 59, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, X.L.; Tol, J.; Hamilton, B.; Rodas, G.; Malliaras, P.; Malliaropoulos, N.; Rizo, V.; Moreno, M.; Jardi, J. Hamstring Muscle Injuries, a Rehabilitation Protocol Purpose. Asian J. Sports Med. 2015, 6, e25411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscle Injuries Clinical Guide 3.0. 2015. Available online: https://muscletechnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/MUSCLE-INJURIES-CLINICAL-GUIDE-3.0-LAST-VERSION.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- Harøy, J.; Clarsen, B.; Wiger, E.G.; Oyen, M.G.; Serner, A.; Thorborg, K.; Holmich, P.; Andersen, T.E.; Bahr, R. The Adductor Strengthening Programme prevents groin problems among male football players: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Sports Med. 2019, 53, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Prampero, P.E.; Botter, A.; Osgnach, C. The energy cost of sprint running and the role of metabolic power in setting top performances. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2015, 115, 451–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisciotti, G.N.; Volpi, P.; Alberti, G.; Aprato, A.; Artina, M.; Auci, A.; Bait, C.; Belli, A.; Bellistri, G.; Bettinsoli, P.; et al. Italian consensus statement (2020) on return to play after lower limb muscle injury in football (soccer). BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2019, 5, e000505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silder, A.; Heiderscheit, B.C.; Thelen, D.G.; Enright, T.; Tuite, M.J. MR observations of long-term musculotendon remodeling following a hamstring strain injury. Skelet. Radiol. 2008, 37, 1101–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reurink, G.; Almusa, E.; Goudswaard, G.J.; Tol, J.L.; Hamilton, B.; Moen, M.H.; Weir, A.; Verhaar, J.A.; Maas, M. No association between fibrosis on magnetic resonance imaging at return to play and hamstring reinjury risk. Am. J. Sports Med. 2015, 43, 1228–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanfilippo, J.L.; Silder, A.; Sherry, M.A.; Tuite, M.J.; Heiderscheit, B.C. Hamstring strength and morphology progression after return to sport from injury. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2013, 45, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvist, J. Rehabilitation following anterior cruciate ligament injury: Current recommendations for sports participation. Sports Med. 2004, 34, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malliaropoulos, N.; Isinkaye, T.; Tsitas, K.; Maffulli, N. Reinjury after acute posterior thigh muscle injuries in elite track and field athletes. Am. J. Sports Med. 2011, 39, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delvaux, F.; Rochcongar, P.; Bruyère, O.; Bourlet, G.; Daniel, C.; Diverse, P.; Reginster, J.Y.; Croisier, J.L. Return-to-play criteria after hamstring injury: Actual medicine practice in professional soccer teams. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2014, 13, 721–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Reurink, G.; Goudswaard, G.J.; Tol, J.L.; Almusa, E.; Moen, M.H.; Weir, A.; Verhaar, J.A.N.; Hamilton, B.; Maas, M. MRI observations at return to play of clinically recovered hamstring injuries. Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 1370–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambaldi, M.; Beasley, I.; Rushton, A. Return to play criteria after hamstring muscle injury in professional football: A Delphi consensus study. Br. J. Sports Med. 2017, 51, 1221–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witvrouw, E.; Danneels, L.; Asselman, P.; D’Have, T.; Cambier, D. Muscle flexibility as a risk factor for developing muscle injuries in male professional soccer players. A prospective study. Am. J. Sports Med. 2003, 31, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, D.A.; Schneider-Kolsky, M.E.; Hoving, J.L.; Malara, F.; Buchbinder, R.; Koulouris, G.; Burke, F.; Bass, C. Longitudinal study comparing sonographic and MRI assessments of acute and healing hamstring injuries. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2004, 183, 975–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavotinek, J.P. Muscle injury: The role of imaging in prognostic assignment and monitoring of muscle repair. Semin. Musculoskelet Radiol. 2010, 14, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, J. Returning to play: The mind does matter. Clin. J. Sport Med. Off. J. Can. Acad. Sport Med. 2005, 15, 432–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazer, D.D. Development and preliminary validation of the Injury-Psychological Readiness to Return to Sport (I-PRRS) scale. J. Athl. Train. 2009, 44, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clover, J.; Wall, J. Return-to-play criteria following sports injury. Clin. Sports Med. 2010, 29, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravé, G.; Granacher, U.; Boullosa, D.; Hackney, A.C.; Zouhal, H. How to Use Global Positioning Systems (GPS) Data to Monitor Training Load in the "Real World" of Elite Soccer. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridehalgh, C.; Moore, A.; Hough, A. Sciatic nerve excursion during a modified passive straight leg raise test in asymptomatic participants and participants with spinally referred leg pain. Man. Ther. 2015, 20, 564–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellis, E.; Ellinoudis, A.; Kofotolis, N. Hamstring Elongation Quantified Using Ultrasonography During the Straight Leg Raise Test in Individuals with Low Back Pain. PM R 2015, 7, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askling, C.M.; Nilsson, J.; Thorstensson, A. A new hamstring test to complement the common clinical examination before return to sport after injury. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2010, 18, 1798–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croisier, J.-L.; Forthomme, B.; Namurois, M.-H.; Vanderthommen, M.; Crielaard, J.M. Hamstring muscle strain recurrence and strength performance disorders. Am. J. Sports Med. 2002, 30, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisciotti, G.N.; Quaglia, A.; Belli, A.; Carimati, G.; Volpi, P. Return to sports after ACL reconstruction: A new functional test protocol. Muscles Ligaments Tendons. J. 2016, 6, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachana, Y.; Chaabène, H.; Nabli, M.A.; Attia, A.; Moualhi, J.; Farhat, N.; Elloumi, M. Test-retest reliability, criterion-related validity, and minimal detectable change of the Illinois agility test in male team sport athletes. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2013, 27, 2752–2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negra, Y.; Chaabene, H.; Hammami, M.; Amara, S.; Sammoud, S.; Mkaouer, B.; Hachana, Y. Agility in Young Athletes: Is It a Different Ability From Speed and Power? J. Strength Cond. Res. 2017, 31, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumitt, J.; Heiderscheit, B.C.; Manske, R.C.; Niemuth, P.E.; Rauh, M.J. Lower extremity functional tests and risk of injury in division iii collegiate athletes. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2013, 8, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ordway, J.D.; Laubach, L.L.; Vanderburgh, P.M.; Jackson, K.J. The Effects of Backwards Running Training on Forward Running Economy in Trained Males. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2016, 30, 763–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouvier, T.; Opplert, J.; Cometti, C.; Babault, N. Acute effects of static stretching on muscle-tendon mechanics of quadriceps and plantar flexor muscles. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2017, 117, 1309–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisciotti, G.N. La tendinopatia degli adduttori nel calciatore: Quando il ritorno alla corsa? Strength Cond. 2013, 5, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Engebretsen, A.H.; Myklebust, G.; Holme, I.; Engebretsen, L.; Bahr, R. Intrinsic risk factors for groin injuries among male soccer players: A prospective cohort study. Am. J. Sports Med. 2010, 38, 2051–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delahunt, E.; McEntee, B.L.; Kennelly, C.; Green, B.S.; Coughlan, G.F. Intrarater reliability of the adductor squeeze test in gaelic games athletes. J. Athl. Train. 2011, 46, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delahunt, E.; Kennelly, C.; McEntee, B.L.; Coughlan, G.F.; Green, B.S. The thigh adductor squeeze test: 45° of hip flexion as the optimal test position for eliciting adductor muscle activity and maximum pressure values. Man Ther. 2011, 16, 476–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, L.; Hignett, T.; Edwards, K. Normative adductor squeeze tests scores in rugby. Phys. Ther. Sport Off. J. Assoc. Chart. Physiother. Sport Med. 2015, 16, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevin, F.; Delahunt, E. Adductor squeeze test values and hip joint range of motion in Gaelic football athletes with longstanding groin pain. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2014, 17, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, H.D.E.; Johal, P.; Falworth, M.S.; Ranawat, V.S.; Dala-Ali, B.; Martin, D.K. Adductor tenotomy: Its role in the management of sports-related chronic groin pain. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2010, 130, 965–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.H.; Yang, S.J.; Ha, J.K.; Jang, S.H.; Seo, J.G.; Kim, J.G. Validation of functional performance tests after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg. Relat. Res. 2012, 24, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.H.; Kim, J.G.; Ha, J.K.; Wang, B.G.; Yang, S.J. Functional performance tests as indicators of returning to sports after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee 2014, 21, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yocum, A.; McCoy, S.W.; Bjornson, K.F.; Mullens, P.; Burton, G.N. Reliability and validity of the standing heel-rise test. Phys. Occup. Pediatr. 2010, 30, 190–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, M.; Lind, K.; Styf, J.; Karlsson, J. The reliability of isokinetic testing of the ankle joint and a heel-raise test for endurance. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2005, 13, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris-Love, M.O.; Shrader, J.A.; Davenport, T.E.; Joe, G.; Rakocevic, G.; McElroy, B.; Dalakas, M. Are repeated single-limb heel raises and manual muscle testing associated with peak plantar-flexor force in people with inclusion body myositis? Phys. Ther. 2014, 94, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumbach, S.F.; Braunstein, M.; Regauer, M.; Böcker, W.; Polzer, H. Diagnosis of Musculus Gastrocnemius Tightness-Key Factors for the Clinical Examination. J. Vis. Exp. 2016, 7, 53446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumbach, S.F.; Braunstein, M.; Seeliger, F.; Borgmann, L.; Böcker, W.; Polzer, H. Ankle dorsiflexion: What is normal? Development of a decision pathway for diagnosing impaired ankle dorsiflexion and M. gastrocnemius tightness. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2016, 136, 1203–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silbernagel, K.G.; Gustavsson, A.; Thomeé, R.; Karlsson, J. Evaluation of lower leg function in patients with Achilles tendinopathy. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2006, 14, 1207–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hewett, T.; Snyder-Mackler, L.; Spindler, K. The drop-jump screening test: Difference in lower limb control by gender and effect of neuromuscular training in female athletes. Am. J. Sports Med. 2007, 35, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, H.C.; Silbernagel, K.G.; Brorsson, A.; Tranberg, R.; Willy, R.W. Individuals Post Achilles Tendon Rupture Exhibit Asymmetrical Knee and Ankle Kinetics and Loading Rates During a Drop Countermovement Jump. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2018, 48, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Severity | Site | Tissue | Relapse |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3A: minor partial lesion | P: proximal | MF: myofascial | R0: first lesion |

| 3B: moderate partial lesion | M: medium | MT: muscular belly and myotendinous junction | R1: first relapse |

| 4: subtotal or total lesion and tendon avulsion | D: distal | T: central tendon or free | R2: second relapse |

| R3: third relapse |

| Hamstring | |

| Specific assessment |

|

| Laboratory test | |

| Field test |

|

| Quadriceps | |

| Specific assessment | |

| Laboratory test |

|

| Field test | |

| Adductors | |

| Specific assessment | |

| Laboratory test | |

| Field test |

|

| Soleus-gastrocnemius | |

| Specific assessment | |

| Laboratory test |

|

| Field test | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Palermi, S.; Massa, B.; Vecchiato, M.; Mazza, F.; De Blasiis, P.; Romano, A.M.; Di Salvatore, M.G.; Della Valle, E.; Tarantino, D.; Ruosi, C.; et al. Indirect Structural Muscle Injuries of Lower Limb: Rehabilitation and Therapeutic Exercise. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2021, 6, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk6030075

Palermi S, Massa B, Vecchiato M, Mazza F, De Blasiis P, Romano AM, Di Salvatore MG, Della Valle E, Tarantino D, Ruosi C, et al. Indirect Structural Muscle Injuries of Lower Limb: Rehabilitation and Therapeutic Exercise. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2021; 6(3):75. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk6030075

Chicago/Turabian StylePalermi, Stefano, Bruno Massa, Marco Vecchiato, Fiore Mazza, Paolo De Blasiis, Alfonso Maria Romano, Mariano Giuseppe Di Salvatore, Elisabetta Della Valle, Domiziano Tarantino, Carlo Ruosi, and et al. 2021. "Indirect Structural Muscle Injuries of Lower Limb: Rehabilitation and Therapeutic Exercise" Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 6, no. 3: 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk6030075

APA StylePalermi, S., Massa, B., Vecchiato, M., Mazza, F., De Blasiis, P., Romano, A. M., Di Salvatore, M. G., Della Valle, E., Tarantino, D., Ruosi, C., & Sirico, F. (2021). Indirect Structural Muscle Injuries of Lower Limb: Rehabilitation and Therapeutic Exercise. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 6(3), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk6030075