The Effect of Joint Mobilization and Manipulation on Proprioception: Systematic Review with Limited Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- In humans, does articular manual therapy (mobilization and/or HVLA thrust manipulation) improve quantitative proprioception outcomes (e.g., JPS/JPSE) compared with sham/placebo, no intervention, or control conditions?

- (2)

- Are effects dependent on the type of technique (mobilization vs. HVLA), anatomical region (spine vs. peripheral joints), participant status (symptomatic vs. asymptomatic), and timing of outcome assessment (immediate vs. follow-up)?

- (3)

- Where data are sufficiently comparable, what is the pooled magnitude of effect on quantitative proprioception outcomes?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.4. Study Selection Process

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.7. Data Synthesis

2.8. Subgroup and Sensitivity Analyses

2.9. Certainty of Evidence and Publication Bias

3. Results

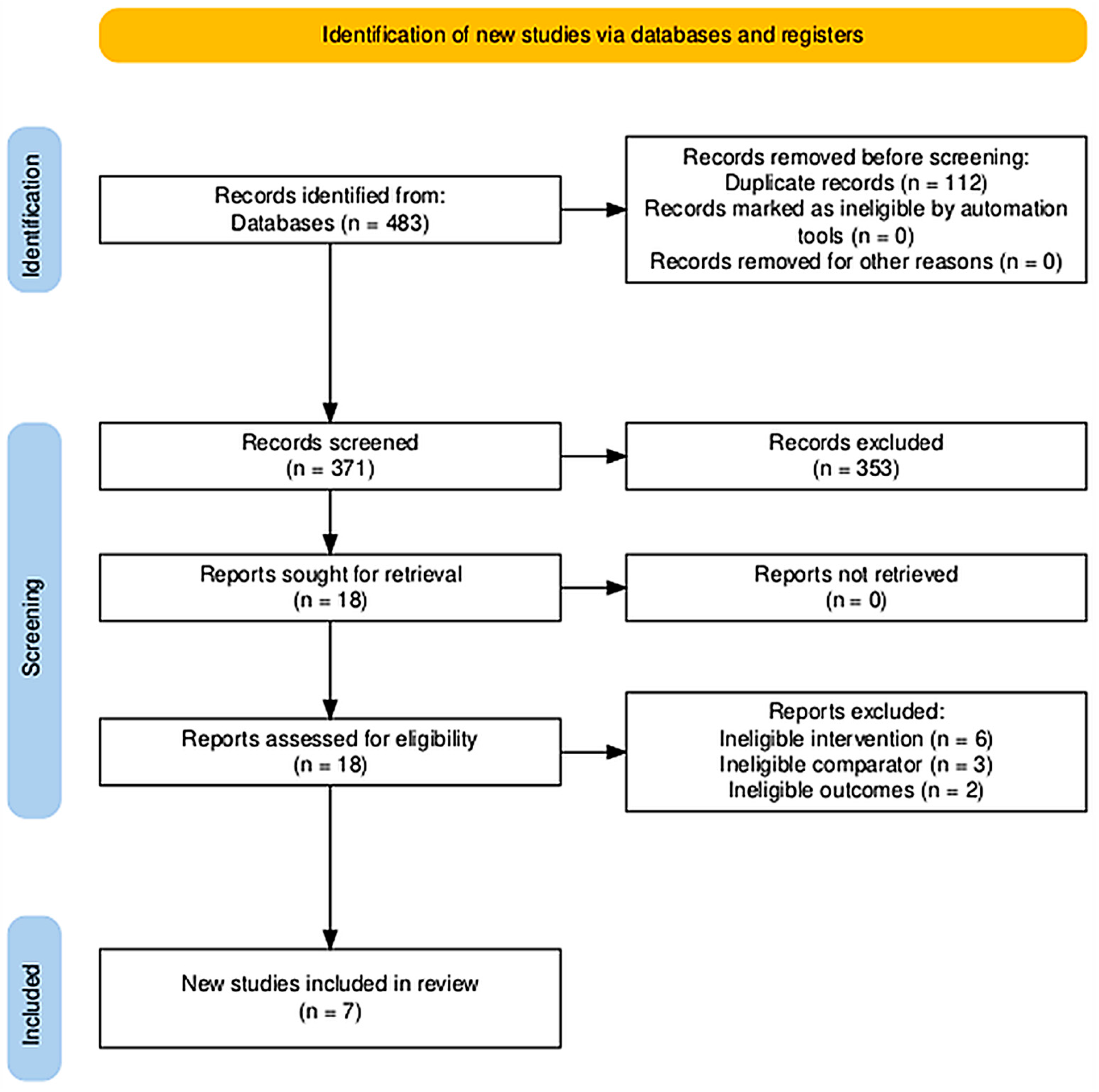

3.1. Study Selection (PRISMA Flow)

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.3. Effects of Manual Joint Mobilization and Manipulation on Proprioception

3.3.1. Cervical Spine Findings

3.3.2. Lumbopelvic and Pelvic Manipulation Findings

3.3.3. Upper Extremity

3.3.4. Proprioceptive Outcome and Heterogeneity

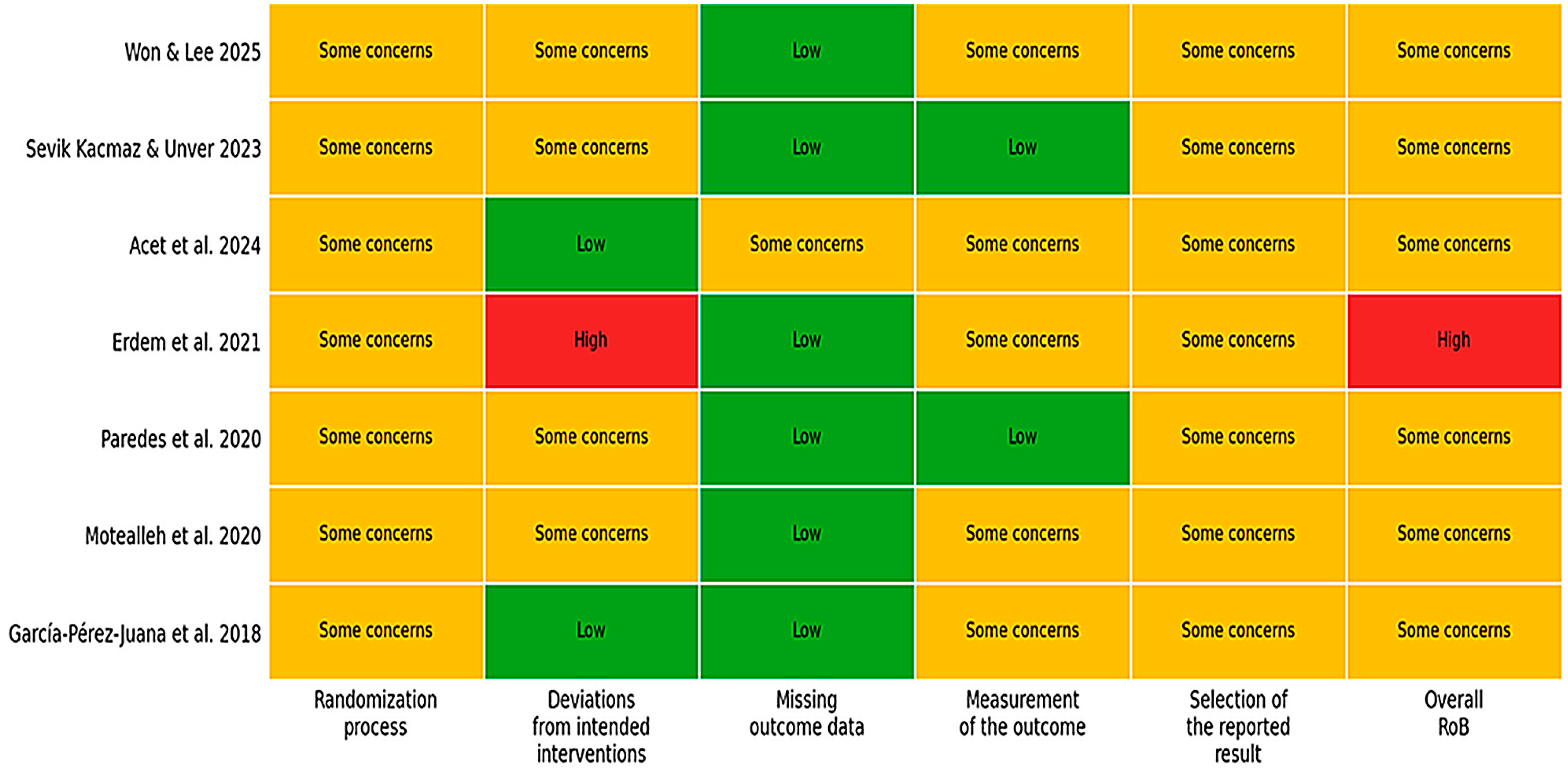

3.4. Risk of Bias Within Studies

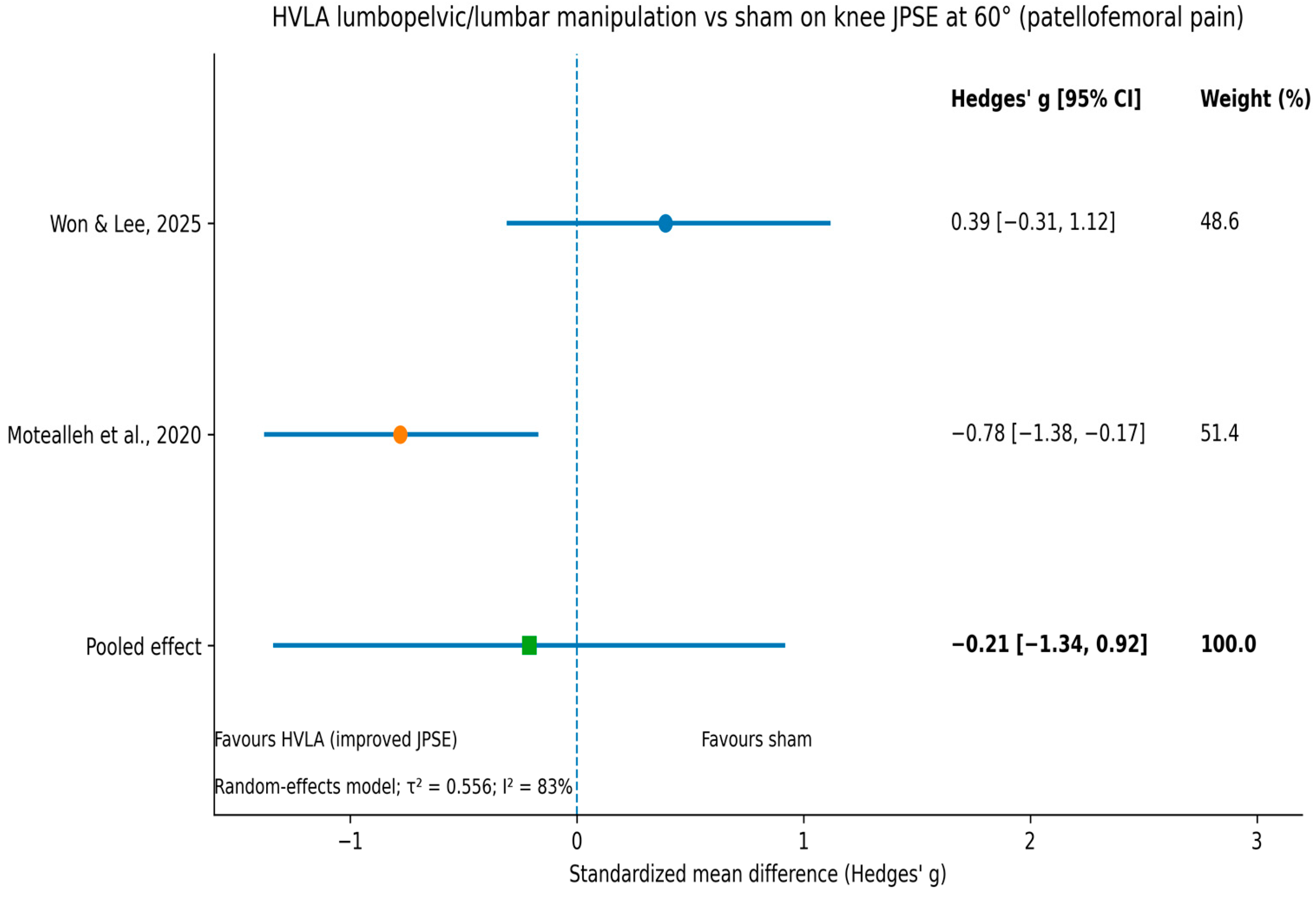

3.5. Meta-Analysis

3.6. Certainty of Evidence (GRADE)

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Main Findings

4.2. Interpretation of Findings by Body Region and Technique

4.2.1. Cervical Spine Interpretation

4.2.2. Lumbopelvic and Pelvic Manipulation Interpretation

4.2.3. Peripheral Joints

4.3. Comparison with Previous Systematic Reviews

4.4. Potential Mechanisms

4.5. Certainty of Evidence and Clinical Implications

4.6. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CINAHL | Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature |

| GRADE | Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation |

| HVLA | High-velocity, low-amplitude (thrust) |

| I2 | I-squared (heterogeneity statistic) |

| JPSE | Joint position sense error |

| JPS | Joint position sense |

| MD | Mean difference |

| MEDLINE | Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online |

| MWM | Mobilization with movement |

| PICOS | Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes, Study design |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PROSPERO | International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trial |

| RoB 2 | Risk of Bias 2 (Cochrane tool) |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SMD | Standardized mean difference |

References

- World Health Organization. Musculoskeletal Conditions (Musculoskeletal Health); WHO Fact sheet; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2021 Low Back Pain Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of low back pain, 1990–2020, its attributable risk factors, and projections to 2050: A systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023, 5, e316–e329. [CrossRef]

- GBD 2021 Neck Pain Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of neck pain, 1990–2020, and projections to 2050: A systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 2024, 6, e142–e155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieza, A.; Causey, K.; Kamenov, K.; Hanson, S.W.; Chatterji, S.; Vos, T. Global estimates of the need for rehabilitation based on the Global Burden of Disease study 2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2021, 396, 2006–2017, Correction in Lancet 2021, 397, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röijezon, U.; Clark, N.C.; Treleaven, J. Proprioception in musculoskeletal rehabilitation. Part 1: Basic science and principles of assessment and clinical interventions. Man. Ther. 2015, 20, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proske, U.; Gandevia, S.C. The proprioceptive senses: Their roles in signaling body shape, body position and movement, and muscle force. Physiol. Rev. 2012, 92, 1651–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riemann, B.L.; Lephart, S.M. The sensorimotor system, part I: The physiologic basis of functional joint stability. J. Athl. Train. 2002, 37, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pinsault, N.; Vuillerme, N. Degradation of cervical joint position sense following muscular fatigue in humans. Spine 2010, 35, 294–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revel, M.; Andre-Deshays, C.; Minguet, M. Cervicocephalic kinesthetic sensibility in patients with cervical pain. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1991, 72, 288–291. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Henry, S.M.; Hitt, J.R.; Jones, S.L.; Bunn, J.Y. Decreased limits of stability in response to postural perturbations in subjects with low back pain. Clin. Biomech. 2015, 30, 650–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, M.H.; Mousavi, S.J.; Kiers, H.; Ferreira, P.; Refshauge, K.; van Dieën, J. Is There a Relationship Between Lumbar Proprioception and Low Back Pain? A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2017, 98, 120–136.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCaskey, M.A.; Schuster-Amft, C.; Wirth, B.; Suica, Z.; de Bruin, E.D. Effects of proprioceptive exercises on pain and function in chronic neck- and low back pain rehabilitation: A systematic literature review. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2014, 15, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Chen, Z.; Ye, X.; Chen, G.; Yang, J.; Zhang, P.; Xie, F.; Guan, Y.; Wu, J.; et al. Proprioceptive Training for Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 699921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Luo, Z.; Wu, D.; Fei, J.; Xie, T.; Su, M. Effectiveness of exercise therapy on chronic ankle instability: A meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, S.Z.; Fritz, J.M.; Silfies, S.P.; Schneider, M.J.; Beneciuk, J.M.; Lentz, T.A.; Gilliam, J.R.; Hendren, S.; Norman, K.S. Interventions for the Management of Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain: Revision 2021. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2021, 51, CPG1–CPG60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haavik-Taylor, H.; Murphy, B. Cervical spine manipulation alters sensorimotor integration: A somatosensory evoked potential study. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2007, 118, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickar, J.G.; Kang, Y.M. Paraspinal muscle spindle responses to the duration of a spinal manipulation under force control. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 2006, 29, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bialosky, J.E.; Bishop, M.D.; Price, D.D.; Robinson, M.E.; George, S.Z. The Mechanisms of Manual Therapy in the Treatment of Musculoskeletal Pain: A Comprehensive Model. Man Ther. 2009, 14, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialosky, J.E.; Beneciuk, J.M.; Bishop, M.D.; Coronado, R.A.; Penza, C.W.; Simon, C.B.; George, S.Z. Unraveling the Mechanisms of Manual Therapy: Modeling an Approach. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2018, 48, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickar, J.G. Neurophysiological effects of spinal manipulation. Spine J. 2002, 2, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, C.A.; Steffen, A.D.; Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; Kim, J.; Chmell, S.J. Joint Mobilization Enhances Mechanisms of Conditioned Pain Modulation in Individuals with Osteoarthritis of the Knee. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2016, 46, 168–176, Erratum in J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2016, 46, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigotsky, A.D.; Bruhns, R.P. The Role of Descending Modulation in Manual Therapy and Its Analgesic Implications: A Narrative Review. Pain Res. Treat. 2015, 2015, 292805, Erratum in Pain Res. Treat. 2017, 2017, 1535473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.J.; Huang, Z.J.; Song, W.B.; Song, X.S.; Fuhr, A.F.; Rosner, A.L.; Ndtan, H.; Rupert, R.L. Attenuation Effect of Spinal Manipulation on Neuropathic and Postoperative Pain Through Activating Endogenous Anti-Inflammatory Cytokine Interleukin 10 in Rat Spinal Cord. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 2016, 39, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acet, N.; Atalay Güzel, N.; Günendi, Z. Effects of Cervical Mobilization on Balance and Proprioception in Patients with Nonspecific Neck Pain. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 2024, 47, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, W. Effects of cervical joint manipulation on joint position sense of normal adults. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2013, 25, 721–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Erdem, E.U.; Ünver, B.; Akbas, E.; Kinikli, G.I. Immediate effects of thoracic manipulation on cervical joint position sense in individuals with mechanical neck pain: A randomized controlled trial. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 2021, 34, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beinert, K.; Lutz, B.; Zieglgänsberger, W.; Diers, M. Seeing the site of treatment improves habitual pain but not cervical joint position sense immediately after manual therapy in chronic neck pain patients. Eur. J. Pain 2019, 23, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Moon, S. Effect of Joint Mobilization in Individuals with Chronic Ankle Instability: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2022, 7, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gross, A.; Langevin, P.; Burnie, S.J.; Bédard-Brochu, M.-S.; Empey, B.; Dugas, E.; Faber-Dobrescu, M.; Andres, C.; Graham, N.; Goldsmith, C.H.; et al. Manipulation and mobilisation for neck pain contrasted against an inactive control or another active treatment. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, CD004249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, J.; Kaplan, L.; Fischer, D.J.; Skelly, A.C. The outcomes of manipulation or mobilization therapy compared with physical therapy or exercise for neck pain: A systematic review. Evid. Based Spine Care J. 2013, 4, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, I.D.; Crawford, C.; Hurwitz, E.L.; Vernon, H.; Khorsan, R.; Booth, M.S.; Herman, P.M. Manipulation and mobilization for treating chronic low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Spine J. 2018, 18, 866–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfort, G.; Haas, M.; Evans, R.L.; Bouter, L.M. Efficacy of spinal manipulation and mobilization for low back pain and neck pain: A systematic review and best evidence synthesis. Spine J. 2004, 4, 335–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Version 6.4); Cochrane: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hedges, L.V. Distribution theory for Glass’s estimator of effect size and related estimators. J. Educ. Stat. 1981, 6, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Vist, G.E.; Kunz, R.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Schünemann, H.J.; GRADE Working Group. GRADE: An emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008, 336, 924–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schünemann, H.J.; Guyatt, G.; Oxman, A. The GRADE approach for diagnostic tests and strategies. In GRADE Handbook for Grading Quality of Evidence and Strength of Recommendations; The GRADE Working Group: Hamilton, ON, Canada, 2013; Available online: https://gdt.gradepro.org/app/handbook/handbook.html (accessed on 26 January 2026).

- García-Pérez-Juana, D.; Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C.; Arias-Buría, J.L.; Cleland, J.A.; Plaza-Manzano, G.; Ortega-Santiago, R. Changes in Cervicocephalic Kinesthetic Sensibility, Widespread Pressure Pain Sensitivity, and Neck Pain After Cervical Thrust Manipulation in Patients with Chronic Mechanical Neck Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 2018, 41, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paredes, R.; Crasto, C.; Magalhães, B.; Carvalho, P. Short-Term Effects of Global Pelvic Manipulation on Knee Joint Position Sense in Asymptomatic Participants: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 2020, 43, 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motealleh, A.; Barzegar, A.; Abbasi, L. The immediate effect of lumbopelvic manipulation on knee pain, knee position sense, and balance in patients with patellofemoral pain: A randomized controlled trial. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2020, 24, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sevik Kacmaz, K.; Unver, B. Immediate Effects of Mulligan Mobilization on Elbow Proprioception in Healthy Individuals: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Single-Blind Study. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 2023, 46, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, J.; Lee, Y. Effects of lumbar spinal manipulation on pain and quadriceps strength in patellofemoral pain syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 2025, 95, 103301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.; Gross, A.; D’Sylva, J.; Burnie, S.J.; Goldsmith, C.H.; Graham, N.; Haines, T.; Brønfort, G.; Hoving, J.L. Manual therapy and exercise for neck pain: A systematic review. Man. Ther. 2010, 15, 334–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsokanos, A.; Livieratou, E.; Billis, E.; Tsekoura, M.; Tatsios, P.; Tsepis, E.; Fousekis, K. The Efficacy of Manual Therapy in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review. Medicina 2021, 57, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Calafiore, D.; Marotta, N.; Longo, U.G.; Vecchio, M.; Zito, R.; Lippi, L.; Ferraro, F.; Invernizzi, M.; Ammendolia, A.; de Sire, A. The efficacy of manual therapy and therapeutic exercise for reducing chronic non-specific neck pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 2025, 38, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, X.; Tao, W.; Xu, X.; Jin, Z.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Gu, X.; Wang, R.; Hua, Y. Do exercise therapies restore the deficits of joint position sense in patients with chronic ankle instability? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. Health Sci. 2023, 5, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luznik, I.; Pajek, M.; Sember, V.; Majcen Rosker, Z. The effectiveness of cervical sensorimotor control training for the management of chronic neck pain disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Montenegrin J. Sports Sci. Med. 2025, 21, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dishman, J.D.; Greco, D.S.; Burke, J.R. Motor-evoked potentials recorded from lumbar erector spinae muscles: A study of corticospinal excitability changes associated with spinal manipulation. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 2008, 31, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, M.D.; Beneciuk, J.M.; George, S.Z. Immediate reduction in temporal sensory summation after spinal manipulation. Spine J. 2011, 11, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plaza-Manzano, G.; Molina-Ortega, F.; Lomas-Vega, R.; Martínez-Amat, A.; Achalandabaso, A.; Hita-Contreras, F. Changes in biochemical markers of pain perception and stress response after spinal manipulation. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2014, 44, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study (Year) | Population | Design/Comparator | Manual Therapy Technique | Proprioceptive Outcome | Main Proprioceptive Findings | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Won & Lee (2025) [44] | Patellofemoral pain syndrome (n = 30) | RCT; lumbar manipulation vs. Placebo | Lumbar spinal manipulation (HVLA) | Knee JPSΕ (30°, 45°, 60°) | NS between-group; within-group improvement at 30° and 45° (MT group). | Small * |

| Sevik Kacmaz & Unver (2023) [43] | Healthy adults (n = 56) | RCT; MWM vs. sham | Mulligan mobilization with movement (elbow) | Elbow JPSE (70°, 110°) | No significant group × time interaction; MWM not superior to sham. | Trivial |

| Acet et al. (2024) [24] | Nonspecific neck pain (n = 60) | RCT; mobilization vs. sham | Cervical joint mobilization | Cervical JPSE (left/right rotation) | Left rotation: significant improvement vs. sham; right rotation: NS between-group. | Small–moderate * |

| Erdem et al. (2021) [26] | Mechanical neck pain (n = 80) | RCT; manipulation vs. no intervention | Thoracic thrust manipulation (HVLA) | Cervical JPSE | NS between-group differences in cervical JPS/JPS error (vs no intervention). | Trivial |

| Paredes et al. (2020) [41] | Asymptomatic adults (n = 26) | RCT; global pelvic manipulation vs. sham | Global pelvic manipulation (HVLA) | Knee JPSΕ (30°, 60°) | NS between- or within-group changes in knee repositioning outcomes. | Small–moderate * |

| Motealleh et al. (2020) [42] | Patellofemoral pain (n = 44) | RCT; lumbopelvic manipulation vs. sham | Lumbopelvic manipulation (HVLA) | Knee JPSE (20°, 60°) | Immediate reduction in knee JPSE at 60° vs. sham (favours MT). | Moderate–large |

| García-Pérez-Juana et al. (2018) [40] | Chronic mechanical neck pain (n = 54) | RCT; cervical thrust vs. sham | Cervical thrust manipulation (HVLA) | Cervical JPSE (extension, rotation) | Significant group × time effects favouring MT; reductions in cervical JPSE exceeded MDC. | Moderate–large |

| Study (Year) | Body Region | Proprioceptive Outcome | Manual Therapy Group (Pre → Post) | Comparator (Pre → Post) | % Change (MT vs. Control) † | Between-Group Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Won & Lee (2025) [44] | Knee | JPSE (°) at 30° | 5.84 → 3.64 | 6.06 → 5.53 | −37.7% vs. −8.7% | NS |

| JPSE (°) at 45° | 4.73 → 2.55 | 4.04 → 3.51 | −45.8% vs. −13.1% | NS | ||

| JPSE (°) at 60° | 3.86 → 4.04 | 5.02 → 3.91 | +4.7% vs. −22.1% | NS | ||

| Sevik Kacmaz & Unver (2023) [43] | Elbow | JPSE (°) at 70° | 7.05 → 3.18 | 6.89 → 4.38 | −54.9% vs. −36.4% | NS |

| JPSE (°) at 110° | 5.85 → 2.62 | 2.33 → 3.96 | −55.2% vs. +69.9% | NS | ||

| Acet et al. (2024) [24] | Cervical | Left rotation JPSE (°) | 4.15 → 1.65 | 4.01 → 3.74 | −60.2% vs. −6.7% | Sig (favours MT) |

| Right rotation JPSE (°) | 4.70 → 2.11 | 5.31 → 4.51 | −55.1% vs. −15.1% | NS | ||

| Erdem et al. (2021) [26] | Cervical | JPSE (°), multiple directions | Median Δ = 0 to −2° | Median Δ = 0° | ≈−40% (extension only) *,‡ | NS |

| Paredes et al. (2020) [41] | Knee | Active JPSE (°) at 30° | ≈5.0 → 4.5 ‡ | ≈7.5 → 7.0 ‡ | −10.0% vs. −6.7% | NS |

| Passive JPSE (°) at 60° | ≈5.5 → 4.5 ‡ | ≈3.8 → 3.5 ‡ | −18.2% vs. −7.9% | NS | ||

| Motealleh et al. (2020) [42] | Knee | JPSE (°) at 60° | 6.58 → 4.48 | 5.91 → 6.05 | −31.9% vs. +2.4% | Sig (favours MT) |

| García-Pérez-Juana et al. (2018) [40] | Cervical | JPSE (°), rotation | 4.1 → 3.0 | 5.1 → 5.5 | −26.8% vs. +7.8% | Sig (favours MT) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hadjisavvas, S.; Themistocleous, I.-C.; Efstathiou, M.A.; Papamichael, E.; Michailidou, C.; Stefanakis, M. The Effect of Joint Mobilization and Manipulation on Proprioception: Systematic Review with Limited Meta-Analysis. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2026, 11, 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk11010059

Hadjisavvas S, Themistocleous I-C, Efstathiou MA, Papamichael E, Michailidou C, Stefanakis M. The Effect of Joint Mobilization and Manipulation on Proprioception: Systematic Review with Limited Meta-Analysis. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2026; 11(1):59. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk11010059

Chicago/Turabian StyleHadjisavvas, Stelios, Irene-Chrysovalanto Themistocleous, Michalis A. Efstathiou, Elena Papamichael, Christina Michailidou, and Manos Stefanakis. 2026. "The Effect of Joint Mobilization and Manipulation on Proprioception: Systematic Review with Limited Meta-Analysis" Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 11, no. 1: 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk11010059

APA StyleHadjisavvas, S., Themistocleous, I.-C., Efstathiou, M. A., Papamichael, E., Michailidou, C., & Stefanakis, M. (2026). The Effect of Joint Mobilization and Manipulation on Proprioception: Systematic Review with Limited Meta-Analysis. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 11(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk11010059