Interrelationships and Shared Variance Among Three Field-Based Performance Tests in Competitive Youth Soccer Players

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Performance Tests

2.3. Statistics

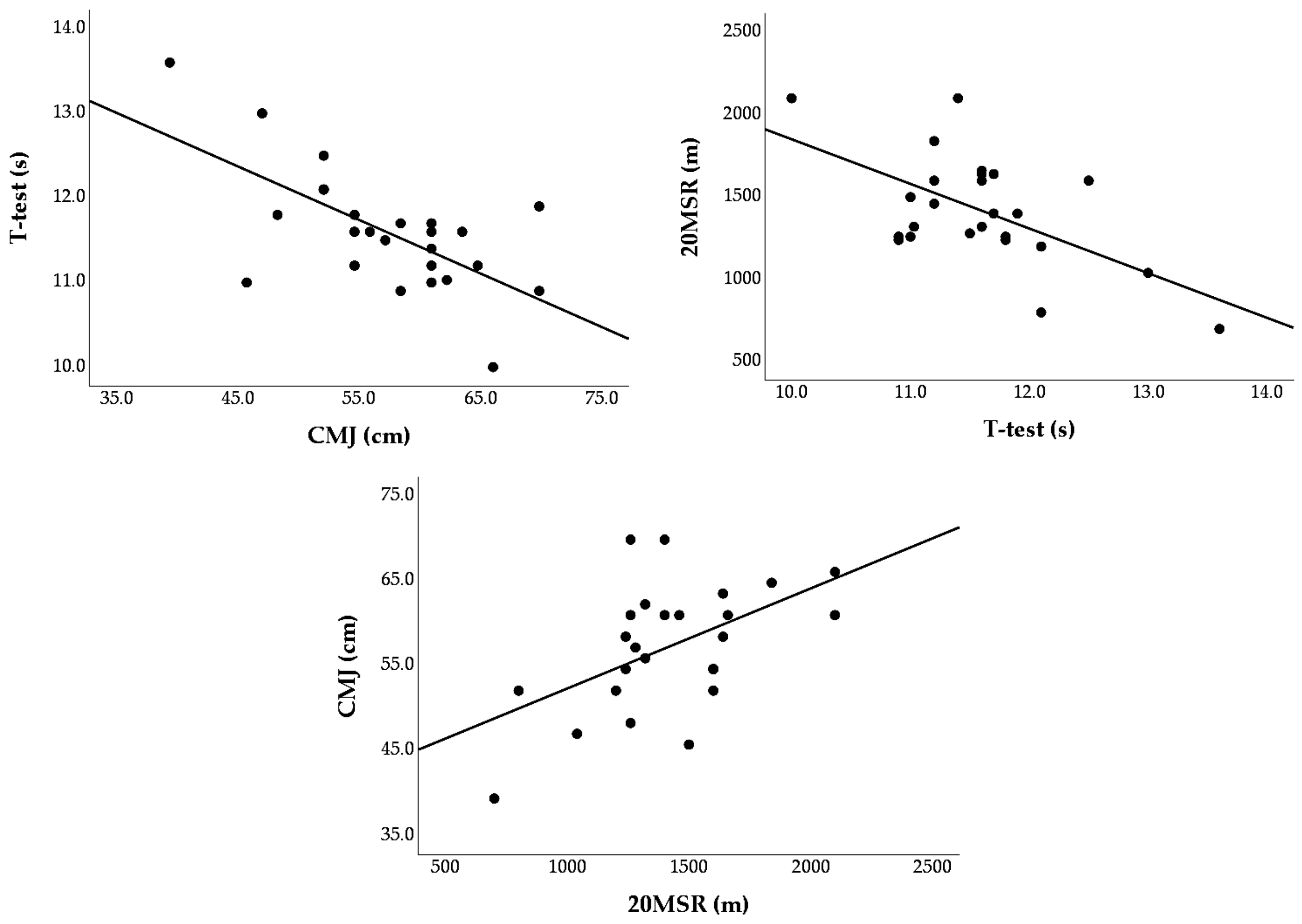

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LBP | lower-body explosive power |

| COD | change-of-direction |

| TT | T-test |

| CMJ | vertical countermovement jump |

| 20MSR | maximal 20 m shuttle run |

| cm | centimeter(s) |

| kg | kilogram(s) |

| m | meter(s) |

| s | second(s) |

| km∙h−1 | kilometer(s) per hour |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for Social Sciences |

| SD | standard deviation |

| r | Pearson’s correlation coefficient |

| R2 | variance |

| ΔR2 | change in variance |

| Min | minimum |

| Max | maximum |

References

- Manna, I.; Khanna, G.L.; Chandra Dhara, P. Effect of training on physiological and biochemical variables of soccer players of different age groups. Asian J. Sports Med. 2010, 1, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slimani, M.; Nikolaidis, P.T. Anthropometric and physiological characteristics of male soccer players according to their competitive level, playing position and age group: A systematic review. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2019, 59, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgans, R.; Bezuglov, E.; Orme, P.; Burns, K.; Rhodes, D.; Babraj, J.; Di Michele, R.; Oliveira, R.F.S. The physical demands of match-play in academy and senior soccer players from the Scottish Premiership. Sports 2022, 10, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asimakidis, N.D.; Bishop, C.J.; Beato, M.; Mukandi, I.N.; Kelly, A.L.; Weldon, A.; Turner, A.N. A survey into the current fitness testing practices of elite male soccer practitioners: From assessment to communicating results. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1376047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asimakidis, N.D.; Mukandi, I.N.; Beato, M.; Bishop, C.; Turner, A.N. Assessment of strength and power capacities in elite male soccer: A systematic review of test protocols used in practice and research. Sports Med. 2024, 54, 2607–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becerra Patiño, B.A.; Montenegro Bonilla, A.D.; Paucar-Uribe, J.D.; Rada-Perdigón, D.A.; Olivares-Arancibia, J.; Yáñez-Sepúlveda, R.; López-Gil, J.F.; Pino-Ortega, J. Characterization of fitness profiles in youth soccer players in response to playing roles rhrough principal component analysis. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellami, M.; Makni, E.; Moalla, W.; Tarwneh, R.; Elloumi, M. Effect of maturation level on normative specific-agility performance metrics and their fitness predictors in soccer players aged 11–18 years. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2024, 16, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- França, C.; Gouveia, É.; Caldeira, R.; Marques, A.; Martins, J.; Lopes, H.; Henriques, R.; Ihle, A. Speed and agility predictors among adolescent male football players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- França, C.; Gouveia, É.; Martins, F.; Ihle, A.; Henriques, R.; Marques, A.; Sarmento, H.; Przednowek, K.; Lopes, H. Lower-body power, body composition, speed, and agility performance among youth soccer players. Sports 2024, 12, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, M.; Drust, B. Testing soccer players. J. Sports Sci. 2005, 23, 601–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.M.; Cook, C.C.; Kilduff, L.P.; Milanović, Z.; James, N.; Sporiš, G.; Fiorentini, B.; Fiorentini, F.; Turner, A.; Vučković, G. Relationship between repeated sprint ability and aerobic capacity in professional soccer players. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 952350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, P.F.; Turner, A.N.; Miller, S.C. Reliability, factorial validity, and interrelationships of five commonly used change of direction speed tests. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2014, 24, 500–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, J.A.; Pupo, J.D.; Reis, D.C.; Borges, L.; Santos, S.G.; Moro, A.R.; Borges, N.G.J. Validity of two methods for estimation of vertical jump height. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2011, 25, 2034–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Léger, L.A.; Mercier, D.; Gadoury, C.; Lambert, J. The multistage 20-metre shuttle run test for aerobic fitness. J. Sports Sci. 1988, 6, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomkinson, G.R.; Lang, J.J.; Blanchard, J.; Léger, L.A.; Tremblay, M.S. The 20-m shuttle run: Assessment and interpretation of data in relation to youth aerobic fitness and health. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2019, 31, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bok, D.; Foster, C. Applicability of field aerobic fitness tests in soccer: Which one to choose? J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2021, 6, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modric, T.; Versic, S.; Sekulic, D.; Liposek, S. Analysis of the association between running performance and game performance indicators in professional soccer players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redkva, P.E.; Paes, M.R.; Fernandez, R.; da-Silva, S.G. Correlation between match performance and field tests in professional soccer players. J. Hum. Kinet. 2018, 62, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, F.M.; Mendes, B.; Nikolaidis, P.T.; Calvete, F.; Carriço, S.; Owen, A.L. Internal training load and its longitudinal relationship with seasonal player wellness in elite professional soccer. Physiol. Behav. 2017, 179, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towlson, C.; Salter, J.; Ade, J.D.; Enright, K.; Harper, L.D.; Page, R.M.; Malone, J.J. Maturity-associated considerations for training load, injury risk, and physical performance in youth soccer: One size does not fit all. J. Sport Health Sci. 2021, 10, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppänen, M.; Uotila, A.; Tokola, K.; Forsman-Lampinen, H.; Kujala, U.M.; Parkkari, J.; Kannus, P.; Pasanen, K.; Vasankari, T. Players with high physical fitness are at greater risk of injury in youth football. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2022, 32, 1625–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, N.; Martinho, D.V.; Pereira, J.R.; Rebelo, A.; Monasterio, X.; Gonzalo-Skok, O.; Valente-dos-Santos, J.; Tavares, F. Injury risk in elite young male soccer players: A review on the impact of growth, maturation, and workload. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2024, 38, 1834–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esco, M.R.; Fedewa, M.V.; Cicone, Z.S.; Sinelnikov, O.A.; Sekulic, D.; Holmes, C.J. Field-based performance tests are related to body fat percentage and fat-free mass, but not body mass index, in youth soccer players. Sports 2018, 6, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hetzler, R.K.; Stickley, C.D.; Lundquist, K.M.; Kimura, I.F. Reliability and accuracy of handheld stopwatches compared with electronic timing in measuring sprint performance. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2008, 22, 1969–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Léger, L.A.; Lambert, J. A maximal multistage 20-m shuttle run test to predict VO2max. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 1982, 49, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, J.R.; Silva, G.; Oliveira, N.; Ribeiro, J.C.; Oliveira, J.F.; Mota, J. Criterion-related validity of the 20-m shuttle run test in youths aged 13-19 years. J. Sports Sci. 2009, 27, 899–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, W.G. A New View of Statistics: A Scale of Magnitudes for Effect Statistics. 2002. Available online: https://www.sportsci.org/resource/stats/effectmag.html (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Jouira, G.; Alexe, D.I.; Tohănean, D.I.; Alexe, C.I.; Tomozei, R.A.; Sahli, S. The Relationship between Dynamic Balance, Jumping Ability, and Agility with 100 m Sprinting Performance in Athletes with Intellectual Disabilities. Sports 2024, 12, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexe, D.I.; Čaušević, D.; Čović, N.; Rani, B.; Tohănean, D.I.; Abazović, E.; Setiawan, E.; Alexe, C.I. The Relationship between Functional Movement Quality and Speed, Agility, and Jump Performance in Elite Female Youth Football Players. Sports 2024, 12, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čaušević, D.; Rani, B.; Gasibat, Q.; Čović, N.; Alexe, C.I.; Pavel, S.I.; Burchel, L.O.; Alexe, D.I. Maturity-Related Variations in Morphology, Body Composition, and Somatotype Features among Young Male Football Players. Children 2023, 10, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlák, J.; Fridvalszki, M.; Kóródi, V.; Szamosszegi, G.; Pólyán, E.; Kovács, B.; Kolozs, B.; Langmár, G.; Rácz, L. Relationship between cognitive functions and agility performance in elite young male soccer players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2024, 38, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicheur, H.; Chauvin, A.; Chassot, S.; Chenevière, X.; Taube, W. Effects of age on the soccer-specific cognitive-motor performance of elite young soccer players: Comparison between objective measurements and coaches’ evaluation. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.X.; Gao, B.H.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Q.; Zhou, J.S.; Tang, Q. Comparing the effects of maximal strength training, plyometric training, and muscular endurance training on explosive performance measures in swimmers. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2025, 24, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Mean ± SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|

| TT (s) | 11.6 ± 0.7 | 10.0 | 13.6 |

| CMJ (cm) | 57.3 ± 7.4 | 39.4 | 70.0 |

| 20MSR (m) | 1418.4 ± 331.6 | 700 | 2100 |

| Dependent Variable | Block | IV (s) | R2 | ∆R2 | β | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TT | 1 | CMJ | 0.423 | - | −0.650 | <0.001 |

| 2 | CMJ + 20MSR | 0.509 | 0.087 | −0.345 | 0.062 | |

| CMJ | 1 | TT | 0.423 | - | −0.650 | <0.001 |

| 2 | TT + 20MSR | 0.453 | 0.030 | 0.216 | 0.282 | |

| 20MSR | 1 | TT | 0.350 | - | −0.434 | 0.002 |

| 2 | TT + CMJ | 0.384 | 0.034 | 0.243 | 0.282 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fields, A.D.; Mohammadnabi, M.A.; Sinelnikov, O.A.; Esco, M.R. Interrelationships and Shared Variance Among Three Field-Based Performance Tests in Competitive Youth Soccer Players. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2026, 11, 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk11010058

Fields AD, Mohammadnabi MA, Sinelnikov OA, Esco MR. Interrelationships and Shared Variance Among Three Field-Based Performance Tests in Competitive Youth Soccer Players. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2026; 11(1):58. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk11010058

Chicago/Turabian StyleFields, Andrew D., Matthew A. Mohammadnabi, Oleg A. Sinelnikov, and Michael R. Esco. 2026. "Interrelationships and Shared Variance Among Three Field-Based Performance Tests in Competitive Youth Soccer Players" Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 11, no. 1: 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk11010058

APA StyleFields, A. D., Mohammadnabi, M. A., Sinelnikov, O. A., & Esco, M. R. (2026). Interrelationships and Shared Variance Among Three Field-Based Performance Tests in Competitive Youth Soccer Players. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 11(1), 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk11010058