Acromiohumeral Distance as a Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarker for Shoulder Disorders: A Systematic Review—Acromiohumeral Distance and Shoulder Disorders

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Reporting Standards

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

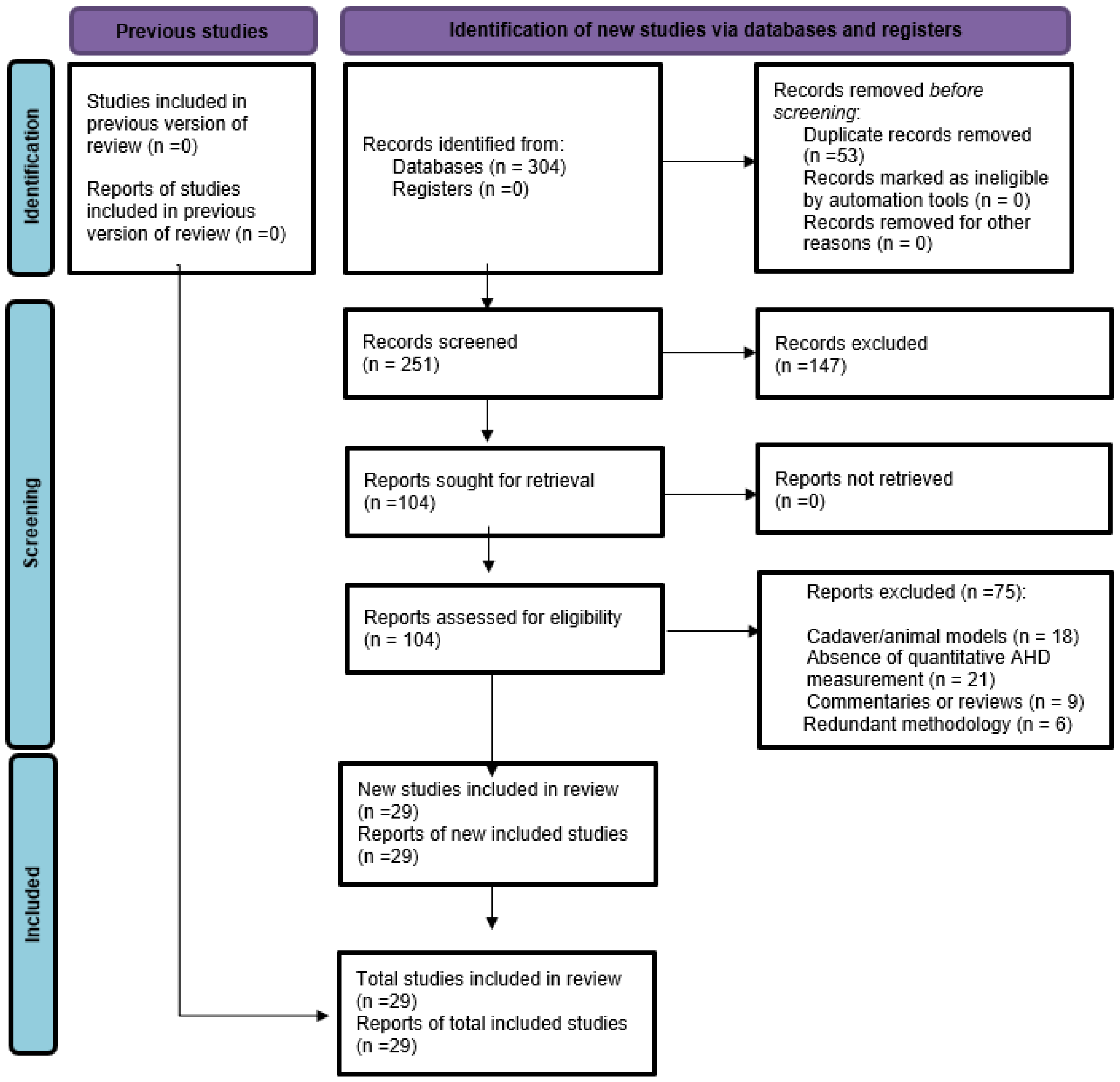

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Level of Evidence

2.7. Methodological Quality Assessment (QUADAS-2)

2.8. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.3. Methodological Quality (QUADAS-2)

| Authors | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | A | B | C | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bahtiyar [25] | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | Low | High | Clear inclusion/exclusion |

| Boulanger [18] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Well-controlled comparative US-MRI study with standardized protocols and blinded assessment. |

| Cavaggion [19] | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Focused on inter-rater reliability in symptomatic vs. asymptomatic population using ultrasound. |

| Dede [26] | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | Low | High | Wireless vs. standard US without independent gold standard comparison. |

| Dede [27] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | MRI-based reliability study with consistent raters and measurements on same day. |

| Deger [4] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Compared AHD measurements across imaging modalities with good internal consistency. |

| Gruber [5] | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Reliability study of radiographic AHD with limited reference standard data |

| Kholinne [10] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Meta-analysis and systematic review with consistent inclusion/exclusion and robust methods. |

| Kizilay [28] | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Volumetric MRI analysis without gold standard comparison. |

| Kocadal [29] | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | MRI-based volume estimation of subacromial space |

| Kozono [20] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Dynamic AHD measured via fluoroscopy |

| Leong [30] | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Focused on reliability of US |

| Lin [1] | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Ultrasound-based AHD in spinal cord injury |

| McCreesh [31] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Systematic review with multiple studies on AHD and clear methodological quality. |

| McCreesh [16] | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Reliability of US in tendinopathy |

| Michener [13] | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | Low | High | Reliability of US for supraspinatus tendon thickness and AHD |

| Navarro-Ledesma [2] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Case–control design with adequate blinding and standard protocols for US. |

| Park [11] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Systematic review and meta-analysis |

| Pieters [3] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Systematic review with high-quality synthesis of conservative therapy impact on AHD. |

| Rentz [17] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Methodological study with blinded raters and reliability statistics (ICC) for US measurements. |

| Sakdapanichkul [33] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Proposes a novel ratio (AHD/Glenoid width) with strong design and radiographic reliability. |

| Sanguanjit [15] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Comparison of upright vs. supine AHD |

| Saupe [8] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Large sample MRI-based study correlating AHD with cuff tears |

| Sürücü [6] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | MRI and radiography bilateral comparison |

| Wynne [24] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | US evaluation of GH mobilization effects on AHD |

| Xu [7] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | US based correlation of AHD and supraspinatus tear severity |

| Xu [9] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Retrospective case–control study using MRI with validated measures of AHD. |

| Yuan [14] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | US-based reliability assessment in healthy population |

3.4. Measurement Techniques and Imaging Modalities

3.5. Reliability and Diagnostic Accuracy

| Imaging Modality | Reliability (ICC) | Sensitivity | Specificity | Clinical Strengths/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound (US) | 0.85–0.98 (excellent) | >85% | 80–90% | Dynamic, portable, low cost; operator-dependent; requires standardization. |

| Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) | 0.57–0.85 (variable) | 70–85% (varies) | 75–85% | Detailed anatomy; postoperative evaluation; higher cost; limited dynamic assessment. |

| Radiography (X-ray) | 0.77–0.85 (moderate) | <60% (partial tears) ~80% (full-thickness) | ~78% (complete tears) | Accessible, inexpensive; projection artifacts; low sensitivity for partial tears. |

3.6. Clinical and Surgical Findings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

Appendix A. Full Search Strategies

References

- Lin, Y.-S.; Boninger, M.L.; Day, K.A.; Koontz, A.M. Ultrasonographic measurement of the acromiohumeral distance in spinal cord injury: Reliability and effects of shoulder positioning. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2015, 38, 700–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Ledesma, S.; Luque-Suarez, A. Comparison of acromiohumeral distance in symptomatic and asymptomatic patient shoulders and those of healthy controls. Clin. Biomech. 2018, 53, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieters, L.; Lewis, J.; Kuppens, K.; Jochems, J.; Bruijstens, T.; Joossens, L.; Struyf, F. An update of systematic reviews examining the effectiveness of conservative physical therapy interventions for subacromial shoulder pain. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2020, 50, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deger, G.U.; Davulcu, C.D.; Karaismailoglu, B.; Palamar, D.; Guven, M.F. Are acromiohumeral distance measurements on conventional radiographs reliable? A prospective study of inter-method agreement with ultrasonography, and assessment of observer variability. Jt. Dis. Relat. Surg. 2023, 35, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, G.; Bernhardt, G.A.; Clar, H.; Zacherl, M.; Glehr, M.; Wurnig, C. Measurement of the acromiohumeral interval on standardized anteroposterior radiographs: A prospective study of observer variability. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2010, 19, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sürücü, S.; Aydın, M.; Çapkın, S.; Karahasanoglu, R.; Yalçın, M.; Atlıhan, D. Evaluation of bilateral acromiohumeral distance on magnetic resonance imaging and radiography in patients with unilateral rotator cuff tears. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2022, 142, 175–180, Erratum in Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2022, 142, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Li, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Ji, B.; Tian, S.; Chen, G. Correlation between acromiohumeral distance and the severity of supraspinatus tendon tear by ultrasound imaging in a Chinese population. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2020, 21, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saupe, N.; Pfirrmann, C.W.; Schmid, M.R.; Jost, B.; Werner, C.M.; Zanetti, M. Association between rotator cuff abnormalities and reduced acromiohumeral distance. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2006, 187, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, F.; Xie, N.; Ji, D.; Gao, Q.; Liu, C. The value of the acromiohumeral distance in the diagnosis and treatment decisions of patients with shoulder pain: A retrospective case-control study. Res. Sq 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kholinne, E.; Kwak, J.-M.; Sun, Y.; Kim, H.; Park, D.; Koh, K.H.; Jeon, I.-H. The relationship between rotator cuff integrity and acromiohumeral distance following open and arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. SICOT-J 2021, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.W.; Chen, Y.T.; Thompson, L.; Kjoenoe, A.; Juul-Kristensen, B.; Cavalheri, V.; McKenna, L. No relationship between the acromiohumeral distance and pain in adults with subacromial pain syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadogan, A.; McNair, P.J.; Laslett, M.; Hing, W.A. Diagnostic accuracy of clinical examination and imaging findings for identifying subacromial pain. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0167738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michener, L.A.; Subasi Yesilyaprak, S.S.; Seitz, A.L.; Timmons, M.K.; Walsworth, M.K. Supraspinatus tendon and subacromial space parameters measured on ultrasonographic imaging in subacromial impingement syndrome. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2015, 23, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Lowder, R.; Aviles-Wetherell, K.; Skroce, C.; Yao, K.V.; Soo Hoo, J. Reliability of point-of-care shoulder ultrasound measurements for subacromial impingement in asymptomatic participants. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 2022, 3, 964613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanguanjit, P.; Apivatgaroon, A.; Boonsun, P.; Srimongkolpitak, S.; Chernchujit, B. The differences of the acromiohumeral interval between supine and upright radiographs of the shoulder. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCreesh, K.M.; Anjum, S.; Crotty, J.M.; Lewis, J.S. Ultrasound measures of supraspinatus tendon thickness and acromiohumeral distance in rotator cuff tendinopathy are reliable. J. Clin. Ultrasound 2016, 44, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rentz, C.; Legerlotz, K. Methodological aspects of the acromiohumeral distance measurement with ultrasonography—Reliability and effects of extrinsic and intrinsic factors in overhead and non-overhead athletes. Sonography 2021, 8, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulanger, S.M.; Mahna, A.; Alenabi, T.; Gatti, A.A.; Culig, O.; Hynes, L.M.; Chopp-Hurley, J.N. Investigating the reliability and validity of subacromial space measurements using ultrasound and MRI. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2023, 18, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavaggion, C.; Navarro-Ledesma, S.; Luque-Suarez, A.; Juul-Kristensen, B.; Voogt, L.; Struyf, F. Subacromial space measured by ultrasound imaging in asymptomatic subjects and patients with subacromial shoulder pain: An inter-rater reliability study. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2023, 39, 2196–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozono, N.; Okada, T.; Takeuchi, N.; Hamai, S.; Higaki, H.; Shimoto, T.; Ikebe, S.; Gondo, H.; Nakanishi, Y.; Senju, T. In Vivo dynamic acromiohumeral distance in shoulders with rotator cuff tears. Clin. Biomech. 2018, 60, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. Levels of Evidence (March 2009); Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2009; Available online: :https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/levels-of-evidence/oxford-centre-for-evidence-based-medicine-levels-of-evidence-march-2009 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Whiting, P.F.; Rutjes, A.W.; Westwood, M.E.; Mallett, S.; Deeks, J.J.; Reitsma, J.B.; Leeflang, M.M.; Sterne, J.A.; Bossuyt, P.M.; QUADAS-2 Group. QUADAS-2: A revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wynne, S.; Hickok, R.; Stump, C.; Andraka, J.M. Changes in Acromiohumeral Distance with Clinician-Applied and Self-Applied Inferior Glenohumeral Joint Mobilizations Measured Using Ultrasound Imaging. JOSPT Open 2025, 3, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahtiyar, B.; Açıkgöz, A.K.; Bozkır, M.G. Evaluation of acromion morphology and subacromial distance in patients with shoulder pain. J. Surg. Med. 2022, 6, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dede, B.T.; Aytekin, E.; Bağcıer, F. Measures of acromiohumeral distance with wireless ultrasound machine in subacromial impingement syndrome: An inter-machine reliability study. J. Ultrason. 2024, 24, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dede, B.T.; Oguz, M.; Bulut, B.; Bagcier, F.; Yildizgoren, M.T.; Aytekin, E. Intra-and Inter-Rater Reliability of Magnetic Resonance Imaging Measurements of Supraspinatus Muscle Thickness, Acromiohumeral Distance, and Coracohumeral Distance in Patients with Shoulder Pain. Selçuk Tıp Derg. 2024, 40, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizilay, Y.O.; Güneş, Z.; Turan, K.; Aktekin, C.N.; Uysal, Y.; Kezer, M.; Camurcu, Y. Volumetric Analysis of Subacromial Space After Superior Capsular Reconstruction for Irreparable Rotator Cuff Tears. Indian J. Orthop. 2023, 57, 967–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocadal, O.; Tasdelen, N.; Yuksel, K.; Ozler, T. Volumetric evaluation of the subacromial space in shoulder impingement syndrome. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2022, 108, 103110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, H.-T.; Tsui, S.; Ying, M.; Leung, V.Y.-F.; Fu, S.N. Ultrasound measurements on acromio-humeral distance and supraspinatus tendon thickness: Test–retest reliability and correlations with shoulder rotational strengths. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2012, 15, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCreesh, K.M.; Crotty, J.M.; Lewis, J.S. Acromiohumeral distance measurement in rotator cuff tendinopathy: Is there a reliable, clinically applicable method? A systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbeivor, C. Needle placement approach to subacromial injection in patients with subacromial impingement syndrome: A systematic review. Musculoskelet. Care 2019, 17, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakdapanichkul, C.; Chantarapitak, N.; Kasemwong, N.; Suwanalai, J.; Wimolsate, T.; Jirawasinroj, T.; Sakolsujin, T.; Kongmalai, P. Transcending Patient Morphometry: Acromiohumeral Interval to Glenoid Ratio as a Universal Diagnostic Tool for Massive Rotator Cuff Tears. Clin. Orthop. Surg. 2024, 16, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasutto, S.; David, O.; Spinelli, M.; Urrutia, D.; Bertocchi Valle, A.; Weigandt, D.; Molina Vargas, I.; Vargas, R.; Navarro, L.; Siemsen, S. Research on body donation willingness in Cordoba-Argentina: Medical and Dentist doctors’ attitude. Rev. Argent. Anatomía Clínica 2019, 11, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Management of rotator cuff injuries. In Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline; American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons: Rosemont, IL, USA, 2019; Volume 24, p. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- American Physical Therapy Association. Medical Treatment Guideline for Shoulder Diagnosis and Treatment; American Physical Therapy Association: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.-S.; Kim, H.; Seitz, A.L.; Tsai, T.-Y.; Jain, N. Computer-aided quantitative ultrasound algorithm of acromiohumeral distance among individuals with spinal cord injury. Front. Phys. 2023, 11, 1075753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, M.; Daniel, M.; Ajiboye, A.; Uraiby, H.; Xu, N.Y.; Bartlett, R.; Hanson, J.; Haas, M.; Spadafore, M.; Grafton-Clarke, C. A scoping review of artificial intelligence in medical education: BEME Guide No. 84. Med. Teach. 2024, 46, 446–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, H.; Teng, F.; Liu, Z.; Yi, Z.; He, J.; Chen, Y.; Geng, B.; Xia, Y.; Wu, M.; Jiang, J. Artificial intelligence aids detection of rotator cuff pathology: A systematic review. Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. 2024, 40, 567–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, A.; Yin, A.L.; Estrin, D.; Greenwald, P.; Fortenko, A. Augmented reality in real-time telemedicine and telementoring: Scoping review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2023, 11, e45464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villani, S.; Pana, J.; Madubuobi, H.; Browne, I.L.; Kimbrow, L.A.; Reece, S. Telerobotic Sonography for Remote Diagnostic Imaging. J. Ultrasound Med. 2023, 42, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Imaging | ICC Intra | ICC Inter | Sensitivity/Specificity | Evidence Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bahtiyar [25] | MRI | 0.93–0.96 | – | – | III |

| Boulanger [18] | US vs. MRI | 0.83–0.97 | 0.63–0.74 | Validity US–MRI 0.21–0.49 | II |

| Cavaggion [19] | US (dynamic) | – | 0.52–0.77 | – | II |

| Dede [26] | US (wireless vs. conventional) | – | 0.96–0.97 | – | II |

| Dede [27] | MRI | 0.94–0.96 | 0.75–0.86 | – | II |

| Deger [4] | X-ray vs. US | 0.79–0.97 | 0.82–0.91 | US–X-ray Sens 0.68–0.75 | II |

| Gruber [5] | X-ray | – | ≤4 mm diff. | Spec >90% (AHD < 6 mm) | I |

| Kholinne [10] | MRI | – | – | High specificity AHD < 6 mm | II †† |

| Kizilay [28] | MRI (3D) | 0.937 | 0.906 | – | III |

| Kocadal [29] | MRI (3D) | >0.70 | – | – | III |

| Kozono [20] | Dynamic fluoroscopy (3D–2D registration) | 0.90 | 0.82 | – | II |

| Leong [30] | US | 0.92 | 0.83 | – | II |

| Lin [1] | US (dynamic) | 0.94 | 0.85 | – | II |

| McCreesh [31] | Systematic review—multi-modality | 0.96 | – | – | I |

| McCreesh [16] | US | >0.92 | >0.90 | – | I |

| Michener [13] | US | 0.98 | – | – | II |

| Navarro-Ledesma [2] | US (dynamic) | 0.88–0.98 | – | – | II |

| Ogbeivor [32] | US/X-ray (contrast-confirmed) | – | – | Indirect pathological thresholds | I |

| Park [11] | Meta-analysis | – | – | MD = 0.28 mm (ns) | I |

| Pieters [3] | Systematic review | – | – | – | I |

| Rentz [17] | US | 0.996 | 0.959–0.997 | – | II |

| Sakdapanichkul [33] | X-ray (AHI + AHIGR) | 0.749–0.923 | 0.866–0.923 | Sens 22–25%; Spec 96–100% | II |

| Sanguanjit [15] | X-ray vs. MRI | 0.668–0.824 | 0.753–0.824 | Sens 28–33%; Spec 100% | II |

| Saupe [8] | X-ray + MRI | 0.77–0.99 | – | Sens 90%; Spec 67% (AHD ≤ 7 mm) | II |

| Sürücü [6] | X-ray + MRI | 0.97 | 0.97 | – | III |

| Wynne [24] | US (dynamic) | 0.876–0.963 | – | – | II |

| Xu [7] | US | 0.98 | – | Correlation with tear severity | III |

| Xu [9] | MRI | 0.906 | – | No AHD–pain correlation | II |

| Yuan [14] | US | 0.76–0.79 | 0.63 | – | II |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arráez-Aybar, L.A.; García-de-Pereda-Notario, C.M.; Palomeque-Del-Cerro, L.; Montoya-Miñano, J.J. Acromiohumeral Distance as a Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarker for Shoulder Disorders: A Systematic Review—Acromiohumeral Distance and Shoulder Disorders. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 478. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040478

Arráez-Aybar LA, García-de-Pereda-Notario CM, Palomeque-Del-Cerro L, Montoya-Miñano JJ. Acromiohumeral Distance as a Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarker for Shoulder Disorders: A Systematic Review—Acromiohumeral Distance and Shoulder Disorders. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2025; 10(4):478. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040478

Chicago/Turabian StyleArráez-Aybar, Luis Alfonso, Carlos Miquel García-de-Pereda-Notario, Luis Palomeque-Del-Cerro, and Juan José Montoya-Miñano. 2025. "Acromiohumeral Distance as a Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarker for Shoulder Disorders: A Systematic Review—Acromiohumeral Distance and Shoulder Disorders" Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 10, no. 4: 478. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040478

APA StyleArráez-Aybar, L. A., García-de-Pereda-Notario, C. M., Palomeque-Del-Cerro, L., & Montoya-Miñano, J. J. (2025). Acromiohumeral Distance as a Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarker for Shoulder Disorders: A Systematic Review—Acromiohumeral Distance and Shoulder Disorders. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 10(4), 478. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040478