Physiological Responder Profiles and Fatigue Dynamics in Prolonged Cycling

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

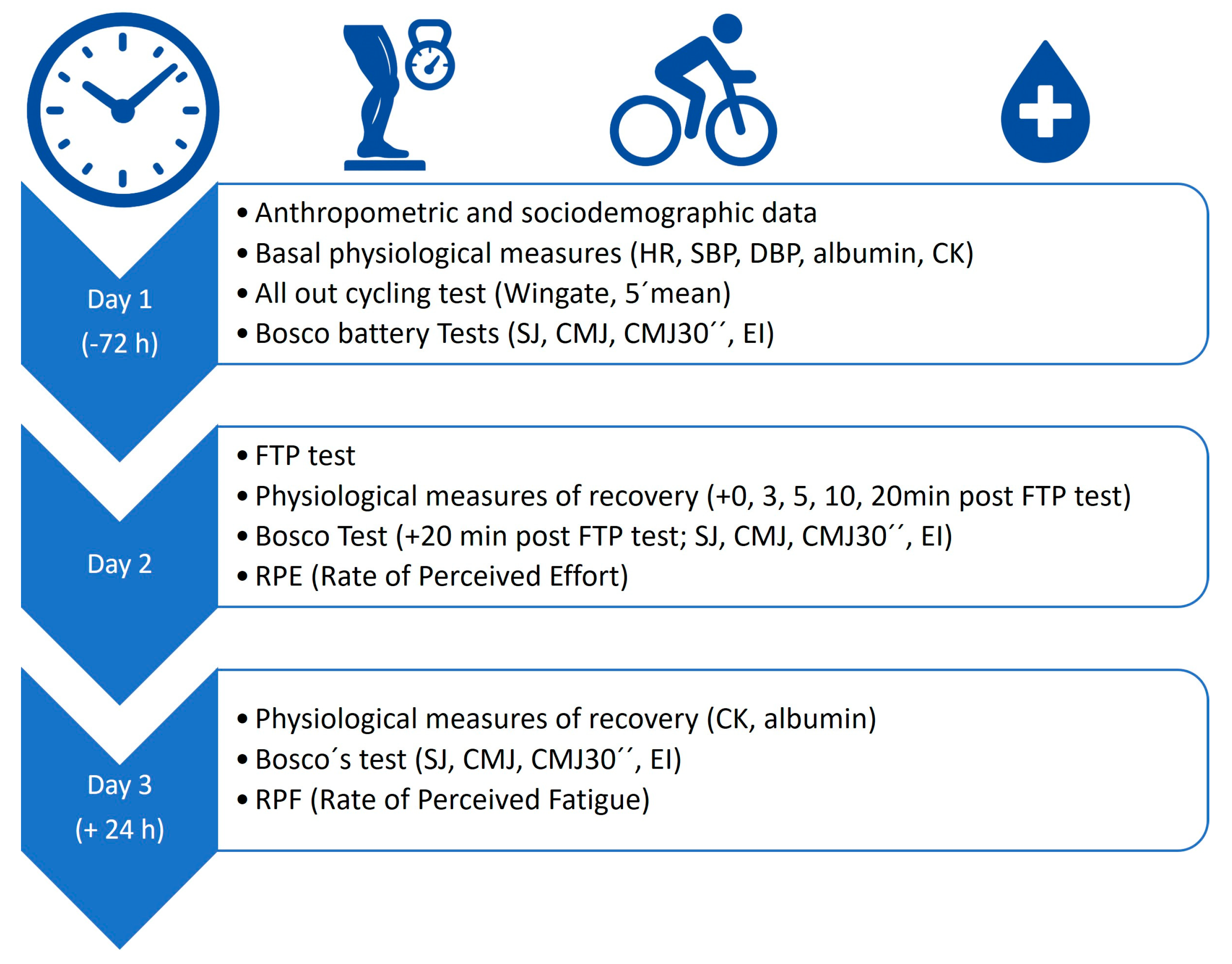

2.1. Study Design and Testing Environment

2.2. Experimental Approach to the Problem

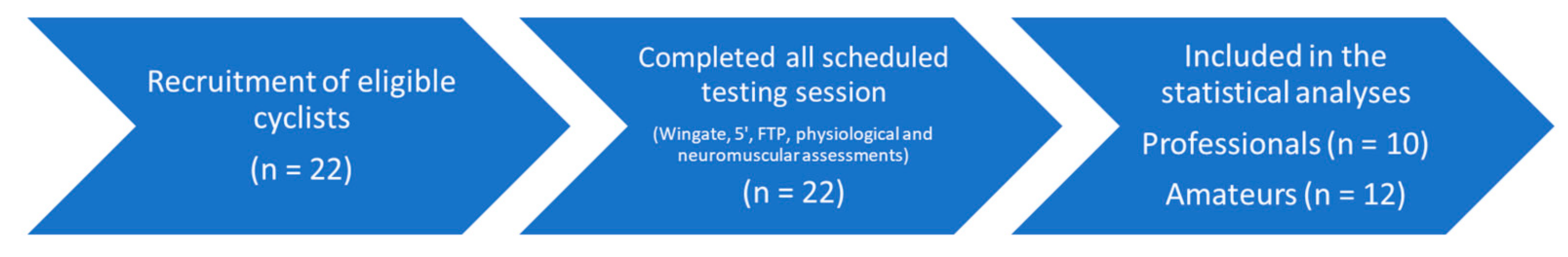

2.3. Participants

2.3.1. Participant Characteristics

2.3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3.3. Classification of Performance Level

2.4. Procedures

2.4.1. Physiological Measurements

2.4.2. Bosco Test Battery Test

2.4.3. All-Out Cycling Tests

2.4.4. Statistical Analysis

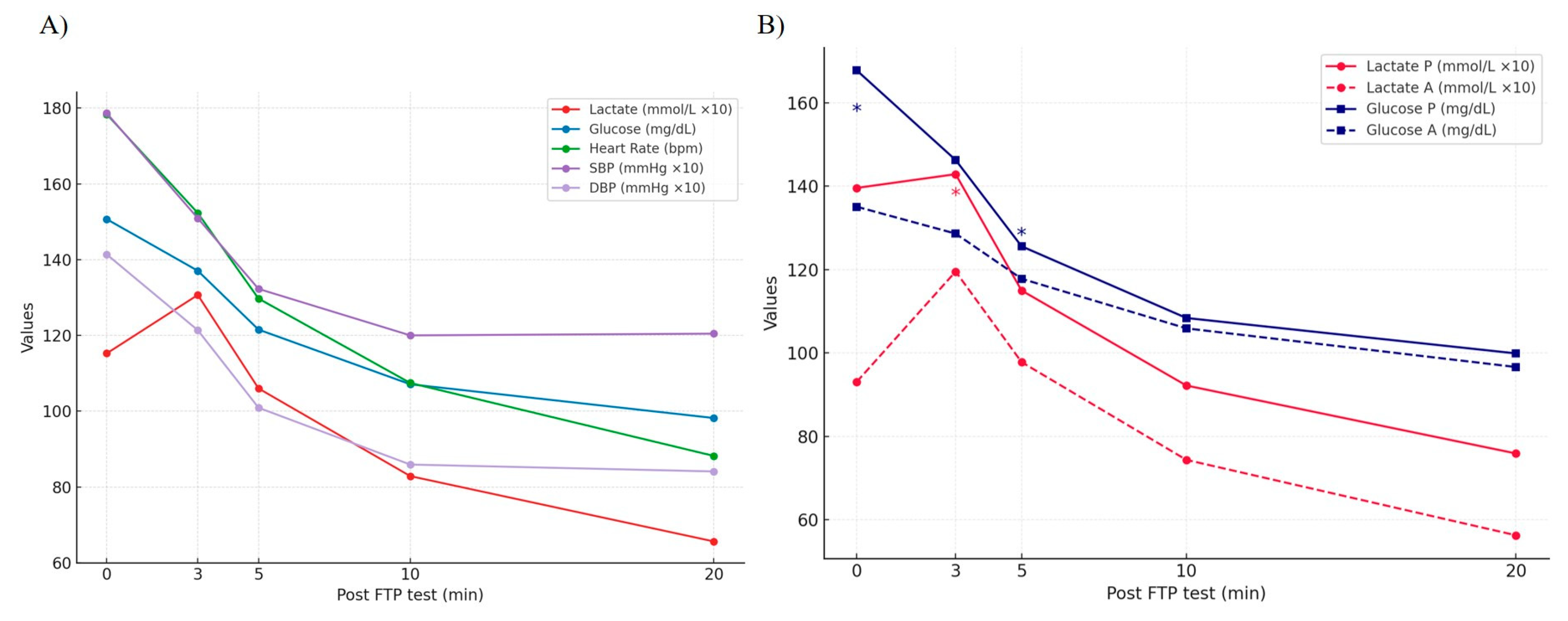

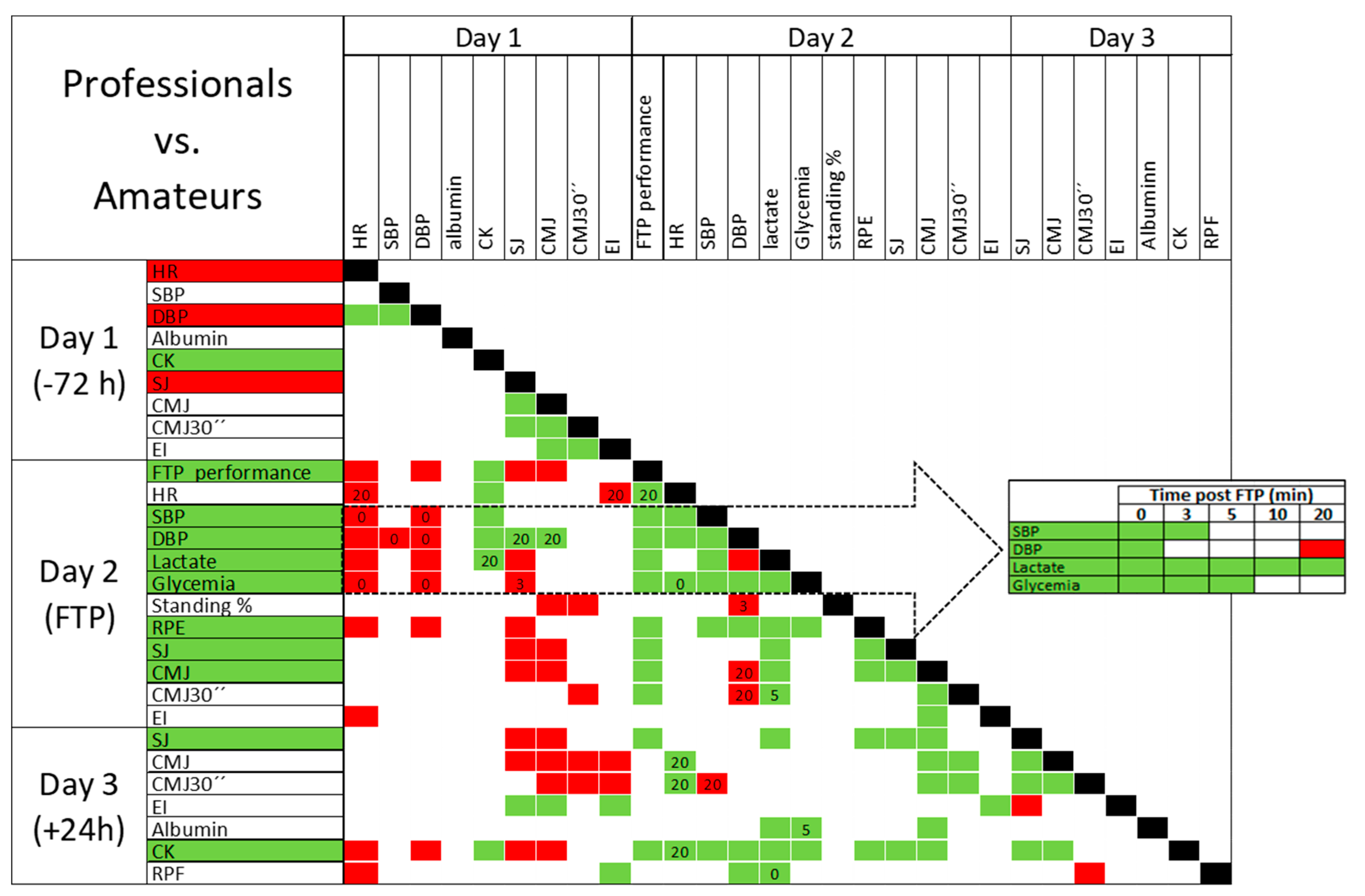

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. FTP Test as a Cyclist-Specific Physiological Performance Indicator

4.2. FTP vs. BT

4.3. FTP vs. Elasticity Index (EI)

4.4. FTP vs. BT and Cycling Position

4.5. Performance and Physiological Recovery Dynamics in Professional vs. Amateur

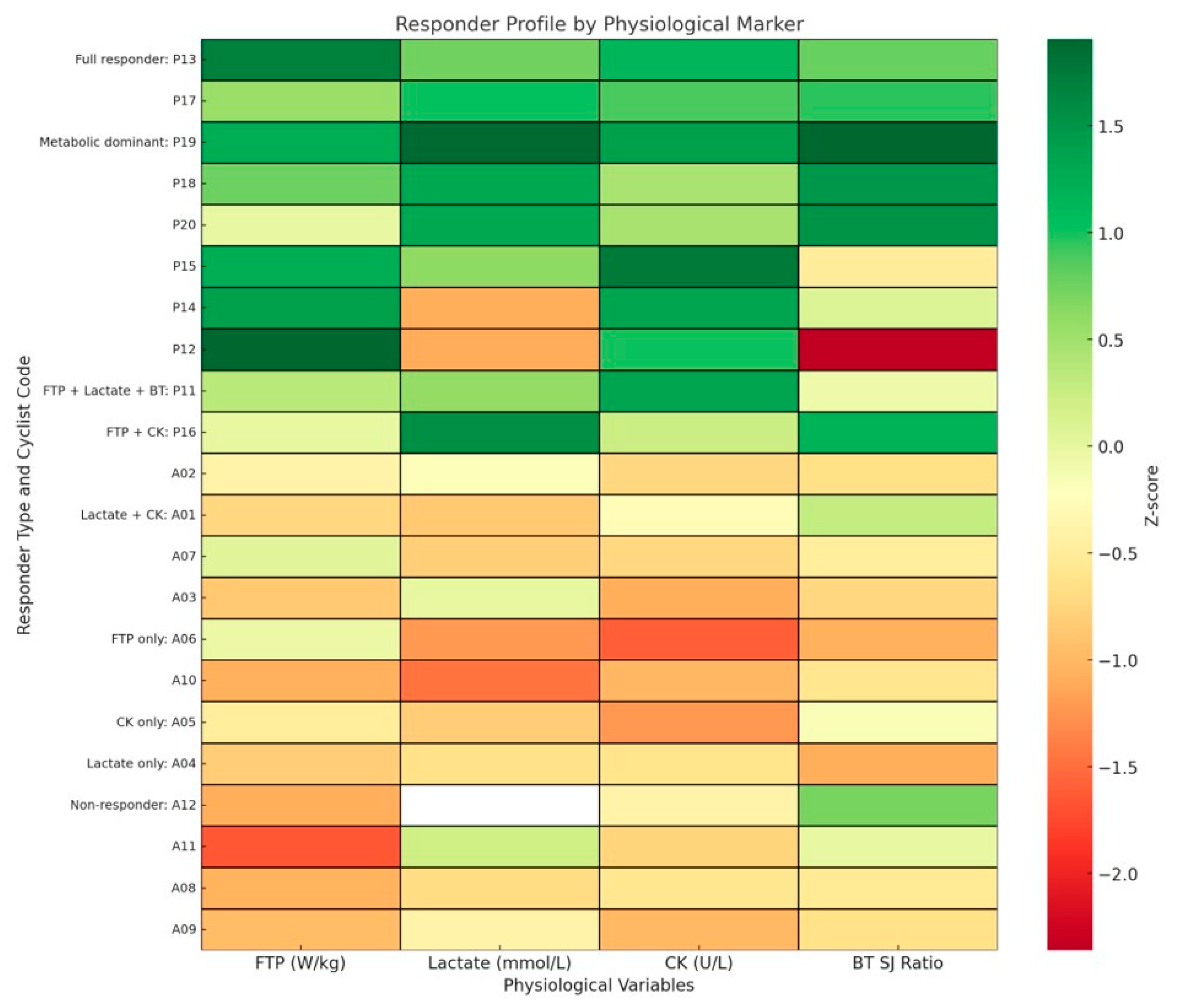

4.6. Individual Physiological Responder Profiles

4.7. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Practical Applications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BT | Bosco’s protocol tests |

| CK | creatine kinase |

| CMJ | countermovement jumps |

| CMJ30 | continuous countermovement jumps for 30 s |

| DBP | diastolic blood pressure |

| EI | elasticity index |

| FTP | factor of threshold power |

| HR | heart rate |

| RPE | rating of perceived effort |

| RPF | rating of perceived fatigue |

| SBP | systolic blood pressure |

| SJ | squat jumps |

| VO2max | maximum oxygen uptake |

References

- Edwards, R.H. Human Muscle Function and Fatigue. In Ciba Foundation Symposium 82-Human Muscle Fatigue: Physiological Mechanisms; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 1981; Volume 82, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amann, M. Central and Peripheral Fatigue: Interaction during Cycling Exercise in Humans. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 43, 2039–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitts, R.H. The Cross-Bridge Cycle and Skeletal Muscle Fatigue. J. Appl. Physiol. 2008, 104, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amann, M.; Wan, H.-Y.; Thurston, T.S.; Georgescu, V.P.; Weavil, J.C. On the Influence of Group III/IV Muscle Afferent Feedback on Endurance Exercise Performance. Exerc. Sport. Sci. Rev. 2020, 48, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundberg, C.W.; Teigen, L.E.; Hunter, S.K.; Fitts, R.H. Cumulative Effects of H+ and Pi on Force and Power of Skeletal Muscle Fibres from Young and Older Adults. J. Physiol. 2025, 603, 187–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amann, M.; Sidhu, S.K.; Weavil, J.C.; Mangum, T.S.; Venturelli, M. Autonomic Responses to Exercise: Group III/IV Muscle Afferents and Fatigue. Auton. Neurosci. 2015, 188, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paavolainen, L.M.; Nummela, A.T.; Rusko, H.K. Neuromuscular Characteristics and Muscle Power as Determinants of 5-km Running Performance. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1999, 31, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paavolainen, L.; Nummela, A.; Rusko, H.; Häkkinen, K. Neuromuscular Characteristics and Fatigue during 10 km Running. Int. J. Sports Med. 1999, 20, 516–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbiss, C.R.; Laursen, P.B. Models to Explain Fatigue during Prolonged Endurance Cycling. Sports Med. 2005, 35, 865–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noakes, T.D. Fatigue Is a Brain-Derived Emotion That Regulates the Exercise Behavior to Ensure the Protection of Whole Body Homeostasis. Front. Physiol. 2012, 3, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St, C.; Noakes, T. Evidence for Complex System Integration and Dynamic Neural Regulation of Skeletal Muscle Recruitment during Exercise in Humans. Br. J. Sports Med. 2004, 38, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- St Clair Gibson, A.; Schabort, E.J.; Noakes, T.D. Reduced Neuromuscular Activity and Force Generation during Prolonged Cycling. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2001, 281, R187–R196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, D.; Marino, F.E.; Cannon, J.; St Clair Gibson, A.; Lambert, M.I.; Noakes, T.D. Evidence for Neuromuscular Fatigue during High-Intensity Cycling in Warm, Humid Conditions. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2001, 84, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swart, J.; Lindsay, T.R.; Lambert, M.I.; Brown, J.C.; Noakes, T.D. Perceptual Cues in the Regulation of Exercise Performance-Physical Sensations of Exercise and Awareness of Effort Interact as Separate Cues. Br. J. Sports Med. 2012, 46, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skorski, S.; Abbiss, C.R. The Manipulation of Pace within Endurance Sport. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peeters, W.M.; Coussens, A.H.; Spears, I.; Jeffries, O. Training, Environmental and Nutritional Practices in Indoor Cycling: An Explorative Cross-Sectional Questionnaire Analysis. Front. Sports Act. Living 2024, 6, 1433368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podlogar, T.; Wallis, G.A. New Horizons in Carbohydrate Research and Application for Endurance Athletes. Sports Med. 2022, 52, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, N.S.; VanDusseldorp, T.A.; Nelson, M.T.; Grgic, J.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; Jenkins, N.D.M.; Arent, S.M.; Antonio, J.; Stout, J.R.; Trexler, E.T.; et al. International Society of Sports Nutrition Position Stand: Caffeine and Exercise Performance. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2021, 18, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Campillo, R.; Alvarez, C.; Henríquez-Olguín, C.; Baez, E.B.; Martínez, C.; Andrade, D.C.; Izquierdo, M. Effects of Plyometric Training on Endurance and Explosive Strength Performance in Competitive Middle- and Long-Distance Runners. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2014, 28, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kons, R.L.; Orssatto, L.B.R.; Ache-Dias, J.; De Pauw, K.; Meeusen, R.; Trajano, G.S.; Dal Pupo, J.; Detanico, D. Effects of Plyometric Training on Physical Performance: An Umbrella Review. Sports Med. Open 2023, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heathcote, S.L.; Hassmén, P.; Zhou, S.; Stevens, C.J. Passive Heating: Reviewing Practical Heat Acclimation Strategies for Endurance Athletes. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galán-Rioja, M.Á.; Gonzalez-Ravé, J.M.; González-Mohíno, F.; Seiler, S. Training Periodization, Intensity Distribution, and Volume in Trained Cyclists: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2023, 18, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, S.R.; McKenzie, D.C. The Laboratory Assessment of Endurance Performance in Cyclists. Can. J. Appl. Physiol. 1994, 19, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett, D.R.; Howley, E.T. Limiting Factors for Maximum Oxygen Uptake and Determinants of Endurance Performance. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2000, 32, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amann, M.; Eldridge, M.W.; Lovering, A.T.; Stickland, M.K.; Pegelow, D.F.; Dempsey, J.A. Arterial Oxygenation Influences Central Motor Output and Exercise Performance via Effects on Peripheral Locomotor Muscle Fatigue in Humans. J. Physiol. 2006, 575, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amann, M.; Venturelli, M.; Ives, S.J.; McDaniel, J.; Layec, G.; Rossman, M.J.; Richardson, R.S. Peripheral Fatigue Limits Endurance Exercise via a Sensory Feedback-Mediated Reduction in Spinal Motoneuronal Output. J. Appl. Physiol. 2013, 115, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, E.V.; St Clair Gibson, A.; Noakes, T.D. Complex Systems Model of Fatigue: Integrative Homoeostatic Control of Peripheral Physiological Systems during Exercise in Humans. Br. J. Sports Med. 2005, 39, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nimmerichter, A.; Eston, R.G.; Bachl, N.; Williams, C. Longitudinal Monitoring of Power Output and Heart Rate Profiles in Elite Cyclists. J. Sports Sci. 2011, 29, 831–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimmerichter, A.; Williams, C.; Bachl, N.; Eston, R. Evaluation of a Field Test to Assess Performance in Elite Cyclists. Int. J. Sports Med. 2010, 31, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavin, T.P.; Van Meter, J.B.; Brophy, P.M.; Dubis, G.S.; Potts, K.N.; Hickner, R.C. Comparison of a Field-Based Test to Estimate Functional Threshold Power and Power Output at Lactate Threshold. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2012, 26, 416–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, H.; Allen, H.; Coggan, A. Training and Racing with a Power Meter; VeloPress: Boulder, CO, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-1-931382-79-3. [Google Scholar]

- Jobson, S.A.; Nevill, A.M.; George, S.R.; Jeukendrup, A.E.; Passfield, L. Influence of Body Position When Considering the Ecological Validity of Laboratory Time-Trial Cycling Performance. J. Sports Sci. 2008, 26, 1269–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, S.; Heinrich, L.; Schumacher, Y.O.; Blum, A.; Roecker, K.; Dickhuth, H.-H.; Schmid, A. Power Output during Stage Racing in Professional Road Cycling. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2006, 38, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, S.; Schumacher, Y.O.; Roecker, K.; Dickhuth, H.-H.; Schoberer, U.; Schmid, A.; Heinrich, L. Power Output during the Tour de France. Int. J. Sports Med. 2007, 28, 756–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.F.; Davison, R.C.; Balmer, J.; Bird, S.R. Reliability of Mean Power Recorded during Indoor and Outdoor Self-Paced 40 Km Cycling Time-Trials. Int. J. Sports Med. 2001, 22, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, S.; Mujika, I.; Cuesta, G.; Goiriena, J.J. Level Ground and Uphill Cycling Ability in Professional Road Cycling. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1999, 31, 878–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, K.; Elmeua, M.; Howatson, G.; Goodall, S. Intensity-Dependent Contribution of Neuromuscular Fatigue after Constant-Load Cycling. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2016, 48, 1751–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paavolainen, L.; Häkkinen, K.; Hämäläinen, I.; Nummela, A.; Rusko, H. Explosive-Strength Training Improves 5-Km Running Time by Improving Running Economy and Muscle Power. J. Appl. Physiol. 1999, 86, 1527–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sands, W.A.; McNeal, J.R.; Ochi, M.T.; Urbanek, T.L.; Jemni, M.; Stone, M.H. Comparison of the Wingate and Bosco Anaerobic Tests. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2004, 18, 810–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Doré, E.; Bedu, M.; Van Praagh, E. Squat Jump Performance during Growth in Both Sexes: Comparison with Cycling Power. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport. 2008, 79, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, C.; Komi, P.V.; Marconnet, P. Fatigue Effects of Marathon Running on Neuromuscular Performance. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 1991, 1, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodacki, A.L.F.; Fowler, N.E.; Bennett, S.J. Vertical Jump Coordination: Fatigue Effects. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2002, 34, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enoka, R.M.; Duchateau, J. Muscle Fatigue: What, Why and How It Influences Muscle Function. J. Physiol. 2008, 586, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordi, M.; Folland, J.; Goodall, S.; Haralabidis, N.; Maden-Wilkinson, T.; Patel, T.S.; Leeder, J.; Barratt, P.; Howatson, G. Mechanical and Morphological Determinants of Peak Power Output in Elite Cyclists. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2020, 30, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deshmukh, A.S.; Steenberg, D.E.; Hostrup, M.; Birk, J.B.; Larsen, J.K.; Santos, A.; Kjøbsted, R.; Hingst, J.R.; Schéele, C.C.; Murgia, M.; et al. Deep Muscle-Proteomic Analysis of Freeze-Dried Human Muscle Biopsies Reveals Fiber Type-Specific Adaptations to Exercise Training. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 304, Erratum in Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdon, P.C.; Cardinale, M.; Murray, A.; Gastin, P.; Kellmann, M.; Varley, M.C.; Gabbett, T.J.; Coutts, A.J.; Burgess, D.J.; Gregson, W.; et al. Monitoring Athlete Training Loads: Consensus Statement. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2017, 12, S2161–S2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujika, I. Quantification of Training and Competition Loads in Endurance Sports: Methods and Applications. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2017, 12, S29–S217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clerico, A.; Giammattei, C.; Cecchini, L.; Lucchetti, A.; Cruschelli, L.; Penno, G.; Gregori, G.; Giampietro, O. Exercise-Induced Proteinuria in Well-Trained Athletes. Clin. Chem. 1990, 36, 562–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Li, G.; Cui, X.; Zhang, D.; Yang, Q.; Mu, X.; Pan, W. Methodological Evaluation and Comparison of Five Urinary Albumin Measurements. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2011, 25, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampietro, O.; Clerico, A.; Cruschelli, L.; Miccoli, R.; Di Palma, L.; Navalesi, R. Measurement of Urinary Albumin Excretion Rate (AER) in Normal and Diabetic Subjects: Comparison of Two Recent Radioimmunoassays. J. Nucl. Med. Allied Sci. 1987, 31, 321–326. [Google Scholar]

- Pueo, B.; Penichet-Tomas, A.; Jimenez-Olmedo, J.M. Reliability and Validity of the Chronojump Open-Source Jump Mat System. Biol. Sport. 2020, 37, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopker, J.; Myers, S.; Jobson, S.A.; Bruce, W.; Passfield, L. Validity and Reliability of the Wattbike Cycle Ergometer. Int. J. Sports Med. 2010, 31, 731–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillod, A.; Pinot, J.; Soto-Romero, G.; Bertucci, W.; Grappe, F. Validity, Sensitivity, Reproducibility, and Robustness of the PowerTap, Stages, and Garmin Vector Power Meters in Comparison with the SRM Device. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2017, 12, 1023–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Reyes, P.; Pareja-Blanco, F.; Cuadrado-Peñafiel, V.; Ortega-Becerra, M.; Párraga, J.; González-Badillo, J.J. Jump Height Loss as an Indicator of Fatigue during Sprint Training. J. Sports Sci. 2019, 37, 1029–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klitzke Borszcz, F.; Tramontin, A.F.; Costa, V.P. Reliability of the Functional Threshold Power in Competitive Cyclists. Int. J. Sports Med. 2020, 41, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, M.L.; Harris, J.E.; Hernández, A.; Gladden, L.B. Blood Lactate Measurements and Analysis during Exercise: A Guide for Clinicians. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2007, 1, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, S.H.; Lilleng, H.; Bekkelund, S.I. Creatine Kinase as Predictor of Blood Pressure and Hypertension. Is It All About Body Mass Index? A Follow-Up Study of 250 Patients. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2014, 16, 820–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helland, C.; Midttun, M.; Saeland, F.; Haugvad, L.; Schäfer Olstad, D.; Solberg, P.A.; Paulsen, G. A Strength-Oriented Exercise Session Required More Recovery Time than a Power-Oriented Exercise Session with Equal Work. PeerJ 2020, 8, e10044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, D.; Heijboer, M. The Anaerobic Power Reserve and Its Applicability in Professional Road Cycling. J. Sports Sci. 2019, 37, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucía, A.; Joyos, H.; Chicharro, J.L. Physiological Response to Professional Road Cycling: Climbers vs. Time Trialists. Int. J. Sports Med. 2000, 21, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, P.G.; Furber, M.J.W.; VAN Someren, K.A.; Antón-Solanas, A.; Swart, J. The Physiological Profile of a Multiple Tour de France Winning Cyclist. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2017, 49, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alejo, L.B.; Montalvo-Pérez, A.; Valenzuela, P.L.; Revuelta, C.; Ozcoidi, L.M.; de la Calle, V.; Mateo-March, M.; Lucia, A.; Santalla, A.; Barranco-Gil, D. Comparative Analysis of Endurance, Strength and Body Composition Indicators in Professional, under-23 and Junior Cyclists. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 945552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mujika, I.; Padilla, S. Physiological and Performance Characteristics of Male Professional Road Cyclists. Sports Med. 2001, 31, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noakes, T.D. Physiological Models to Understand Exercise Fatigue and the Adaptations That Predict or Enhance Athletic Performance. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2000, 10, 123–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobson, S.A.; Passfield, L.; Atkinson, G.; Barton, G.; Scarf, P. The Analysis and Utilization of Cycling Training Data. Sports Med. 2009, 39, 833–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutton, R.S.; Nelson, D.L. Stretch Sensitivity of Golgi Tendon Organs in Fatigued Gastrocnemius Muscle. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1986, 18, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, H.J.; Patla, A.E. Maximal Aerobic Power: Neuromuscular and Metabolic Considerations. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1992, 24, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noakes, T.D. Implications of Exercise Testing for Prediction of Athletic Performance: A Contemporary Perspective. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1988, 20, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosco, C.; Komi, P.V.; Tihanyi, J.; Fekete, G.; Apor, P. Mechanical Power Test and Fiber Composition of Human Leg Extensor Muscles. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 1983, 51, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosco, C.; Luhtanen, P.; Komi, P.V. A Simple Method for Measurement of Mechanical Power in Jumping. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 1983, 50, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuigan, M.R.; Doyle, T.L.A.; Newton, M.; Edwards, D.J.; Nimphius, S.; Newton, R.U. Eccentric Utilization Ratio: Effect of Sport and Phase of Training. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2006, 20, 992–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, C.; Avela, J.; Komi, P.V. The Stretch-Shortening Cycle: A Model to Study Naturally Occurring Neuromuscular Fatigue. Sports Med. 2006, 36, 977–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozinc, Ž.; Žitnik, J.; Smajla, D.; Šarabon, N. The Difference between Squat Jump and Countermovement Jump in 770 Male and Female Participants from Different Sports. Eur. J. Sport. Sci. 2022, 22, 985–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishikawa, M.; Komi, P.V.; Grey, M.J.; Lepola, V.; Bruggemann, G.-P. Muscle-Tendon Interaction and Elastic Energy Usage in Human Walking. J. Appl. Physiol. 2005, 99, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welbergen, E.; Clijsen, L.P. The Influence of Body Position on Maximal Performance in Cycling. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 1990, 61, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Origenes, M.M.; Blank, S.E.; Schoene, R.B. Exercise Ventilatory Response to Upright and Aero-Posture Cycling. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1993, 25, 608–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, W.D.; Betz, C.B.; Humphrey, R.H. Effects of Rider Position on Continuous Wave Doppler Responses to Maximal Cycle Ergometry. Br. J. Sports Med. 1994, 28, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryschon, T.W.; Stray-Gundersen, J. The Effect of Body Position on the Energy Cost of Cycling. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1991, 23, 949–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkemeier, Q.N.; Alumbaugh, B.W.; Gillum, T.; Coburn, J.; Kim, J.-K.; Reeder, M.; Fechtner, C.A.; Smith, G.A. Physiological and Biomechanical Differences Between Seated and Standing Uphill Cycling. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2020, 13, 996–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, I.; Dix, C.; Frazer, C. Effect of Body Position during Cycling on Heart Rate, Pulmonary Ventilation, Oxygen Uptake and Work Output. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 1978, 18, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, H.; Bassett, D.R.; Turner, M.J. Exaggerated Blood Pressure Response to Maximal Exercise in Endurance-Trained Individuals. Am. J. Hypertens. 1996, 9, 1099–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Molina, L.; Elosua, R.; Marrugat, J.; Pons, S. Relation of Maximum Blood Pressure during Exercise and Regular Physical Activity in Normotensive Men with Left Ventricular Mass and Hypertrophy. Am. J. Cardiol. 1999, 84, 890–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, A.S.; Okoshi, M.P.; Padovani, C.R.; Okoshi, K. Doppler Echocardiography in Athletes from Different Sports. Med. Sci. Monit. 2013, 19, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krämer, B.K.; Kernz, M.; Ress, K.M.; Pfohl, M.; Müller, G.A.; Schmülling, R.M.; Risler, T. Influence of Strenuous Exercise on Albumin Excretion. Clin. Chem. 1988, 34, 2516–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huttunen, N.P.; Käär, M.L.; Pietiläinen, M.; Vierikko, P.; Reinilä, M. Exercise-Induced Proteinuria in Children and Adolescents. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 1981, 41, 583–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poortmans, J.R.; Labilloy, D. The Influence of Work Intensity on Postexercise Proteinuria. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 1988, 57, 260–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poortmans, J.R.; Henrist, A. The Influence of Air-Cushion Shoes on Post-Exercise Proteinuria. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 1989, 29, 213–217. [Google Scholar]

- Poortmans, J.R.; Jourdain, M.; Heyters, C.; Reardon, F.D. Postexercise Proteinuria in Rowers. Can. J. Sport. Sci. 1990, 15, 126–130. [Google Scholar]

- Poortmans, J.R.; Vanderstraeten, J. Kidney Function during Exercise in Healthy and Diseased Humans. An Update. Sports Med. 1994, 18, 419–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dohm, G.L. Protein Nutrition for the Athlete. Clin. Sports Med. 1984, 3, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hargreaves, M.; Spriet, L.L. Skeletal Muscle Energy Metabolism during Exercise. Nat. Metab. 2020, 2, 817–828, Erratum in Nat. Metab. 2020, 2, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junior, P.B.; de Andrade, V.L.; Campos, E.Z.; Kalva-Filho, C.A.; Zagatto, A.M.; de Araújo, G.G.; Papoti, M. Effect of Endurance Training on The Lactate and Glucose Minimum Intensities. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2018, 17, 117–123. [Google Scholar]

- Brancaccio, P.; Limongelli, F.M.; Maffulli, N. Monitoring of Serum Enzymes in Sport. Br. J. Sports Med. 2006, 40, 96–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamizrak, S.O.; Ergen, E.; Töre, I.R.; Akgün, N. Changes in Serum Creatine Kinase, Lactate Dehydrogenase and Aldolase Activities Following Supramaximal Exercise in Athletes. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 1994, 34, 141–146. [Google Scholar]

- Garry, J.P.; McShane, J.M. Postcompetition Elevation of Muscle Enzyme Levels in Professional Football Players. MedGenMed 2000, 2, E4. [Google Scholar]

- Koutedakis, Y.; Raafat, A.; Sharp, N.C.; Rosmarin, M.N.; Beard, M.J.; Robbins, S.W. Serum Enzyme Activities in Individuals with Different Levels of Physical Fitness. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 1993, 33, 252–257. [Google Scholar]

- Brancaccio, P.; Maffulli, N.; Limongelli, F.M. Creatine Kinase Monitoring in Sport Medicine. Br. Med. Bull. 2007, 81–82, 209–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcora, S.M.; Staiano, W. The Limit to Exercise Tolerance in Humans: Mind over Muscle? Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010, 109, 763–770, Erratum in Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010, 110, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGuigan, M. Monitoring Training and Performance in Athletes. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2018, 50, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeusen, R.; Duclos, M.; Foster, C.; Fry, A.; Gleeson, M.; Nieman, D.; Raglin, J.; Rietjens, G.; Steinacker, J.; Urhausen, A.; et al. Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of the Overtraining Syndrome: Joint Consensus Statement of the European College of Sport Science and the American College of Sports Medicine. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2013, 45, 186–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halson, S.L. Monitoring Training Load to Understand Fatigue in Athletes. Sports Med. 2014, 44 (Suppl. S2), S139–S147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gathercole, R.J.; Sporer, B.C.; Stellingwerff, T.; Sleivert, G.G. Comparison of the Capacity of Different Jump and Sprint Field Tests to Detect Neuromuscular Fatigue. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2015, 29, 2522–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billat, V.L.; Sirvent, P.; Py, G.; Koralsztein, J.-P.; Mercier, J. The Concept of Maximal Lactate Steady State: A Bridge between Biochemistry, Physiology and Sport Science. Sports Med. 2003, 33, 407–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons, M.S.; Hunter, S.K.; Ansdell, P. Sex Differences in Fatigability and Recovery Following a 5 Km Running Time Trial in Recreationally Active Adults. Eur. J. Sport. Sci. 2023, 23, 2349–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menting, S.G.P.; Edwards, A.M.; Hettinga, F.J.; Elferink-Gemser, M.T. Pacing Behaviour Development and Acquisition: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. Open 2022, 8, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tidmas, V.; Brazier, J.; Bottoms, L.; Muniz, D.; Desai, T.; Hawkins, J.; Sridharan, S.; Farrington, K. Ultra-Endurance Participation and Acute Kidney Injury: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Env. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 16887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostapiuk-Karolczuk, J.; Dziewiecka, H.; Bojsa, P.; Cieślicka, M.; Zawadka-Kunikowska, M.; Wojciech, K.; Kasperska, A. Biochemical and Psychological Markers of Fatigue and Recovery in Mixed Martial Arts Athletes during Strength and Conditioning Training. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B.; Li, F.; Su, B. Wearable Sensors for Precise Exercise Monitoring and Analysis. Biosensors 2025, 15, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schubert-Olesen, O.; Kröger, J.; Siegmund, T.; Thurm, U.; Halle, M. Continuous Glucose Monitoring and Physical Activity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 12296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Professional | Amateur | All Participants | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main features | Age (years) | 26.7 ± 7.2 | 28.4 ± 5.8 | 27.6 ± 6.4 | 0.540 |

| Height (cm) | 178.9 ± 4.7 | 176.0 ± 5.9 | 177.3 ± 5.5 | 0.220 | |

| Weight (kg) | 63.9 ± 3.2 | 66.9 ± 4.4 | 65.5 ± 4.1 | 0.080 | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 19.9 ± 0.7 | 21.6 ± 1.3 | 20.9 ± 1.3 | 0.001 * | |

| 20 min FTP test | Mean power (W) | 347.4 ± 12.6 | 284.0 ± 20.0 | 312.8 ± 36.3 | <0.001 * |

| Relative mean power (W/kg) | 5.4 ± 0.3 | 4.3 ± 0.4 | 4.8 ± 0.7 | <0.001 * | |

| Standing time (%) | 27.6 ± 15.1 | 27.3 ± 12.7 | 27.4 ± 13.5 | 0.960 | |

| Wingate test | Mean power (W) | 826.7 ± 104.3 | 581.3 ± 91.9 | 692.9 ± 157.3 | <0.001 * |

| Relative mean power (W/kg) | 12.9 ± 1.6 | 8.7 ± 1.2 | 10.6 ± 2.5 | <0.001 * | |

| Peak power (W) | 1052.5 ± 151.9 | 753.4 ± 97.7 | 889.3 ± 195.3 | <0.001 * | |

| 5 min test | Mean power (W) | 409.7 ± 28.3 | 345.7 ± 32.2 | 374.8 ± 44.1 | <0.001 * |

| Relative mean power (W/kg) | 6.4 ± 0.5 | 5.2 ± 0.8 | 5.7 ± 0.8 | <0.001 * |

| MEASURES | TIME | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (DAY 1) PRE- FTP TEST | (DAY 2) POST-FTP TEST | (DAY 3) POST-FTP TEST | ||||||

| −72 h | 0 min | 3 min | 5 min | 10 min | 20 min | 24 h | ||

| All out cycling test | 30″ Peak | +C | ||||||

| 30″ mean | +C | |||||||

| 5’mean | +C, +P | |||||||

| Bosco Test | SJ | −C | +C | +C | ||||

| CMJ | −C | +C | −C | |||||

| CMJ30″ | −P | +C | −P | |||||

| EI | −P | −P | ||||||

| Perceived effort | RPE | +C, +A | ||||||

| Physiological values | CK | +C | +C, +A | |||||

| HR | −C | +P | +C | |||||

| SBP | +C, +P | +C, +P | ||||||

| DBP | −C | +C | +C | −C, −P | ||||

| Glycaemia | +C | +C, +A | +A | +A | ||||

| Lactate | +C | +C | +C, −P, +A | +C | ||||

| HR | SBP | DBP | LACTATE | GLYCAEMIA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | |||||

| SBP | |||||

| DBP | |||||

| LACTATE | |||||

| GLYCAEMIA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Odriozola, A.; Tirnauca, C.; Corbi, F.; González, A.; Álvarez-Herms, J. Physiological Responder Profiles and Fatigue Dynamics in Prolonged Cycling. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 472. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040472

Odriozola A, Tirnauca C, Corbi F, González A, Álvarez-Herms J. Physiological Responder Profiles and Fatigue Dynamics in Prolonged Cycling. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2025; 10(4):472. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040472

Chicago/Turabian StyleOdriozola, Adrian, Cristina Tirnauca, Francesc Corbi, Adriana González, and Jesús Álvarez-Herms. 2025. "Physiological Responder Profiles and Fatigue Dynamics in Prolonged Cycling" Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 10, no. 4: 472. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040472

APA StyleOdriozola, A., Tirnauca, C., Corbi, F., González, A., & Álvarez-Herms, J. (2025). Physiological Responder Profiles and Fatigue Dynamics in Prolonged Cycling. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 10(4), 472. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040472