Monitoring Treadmill Physical Exercise and Recovery in Elite Water Polo Players with Local Muscle Oxygen Saturation Measurements—Regional and Sex Differences

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedures

2.2.1. Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing

2.2.2. Muscle Oxygen Saturation Measurements

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

3.2. Muscle Oxygen Saturation Values

3.3. Muscle Oxygen Saturation Changes During Exercise

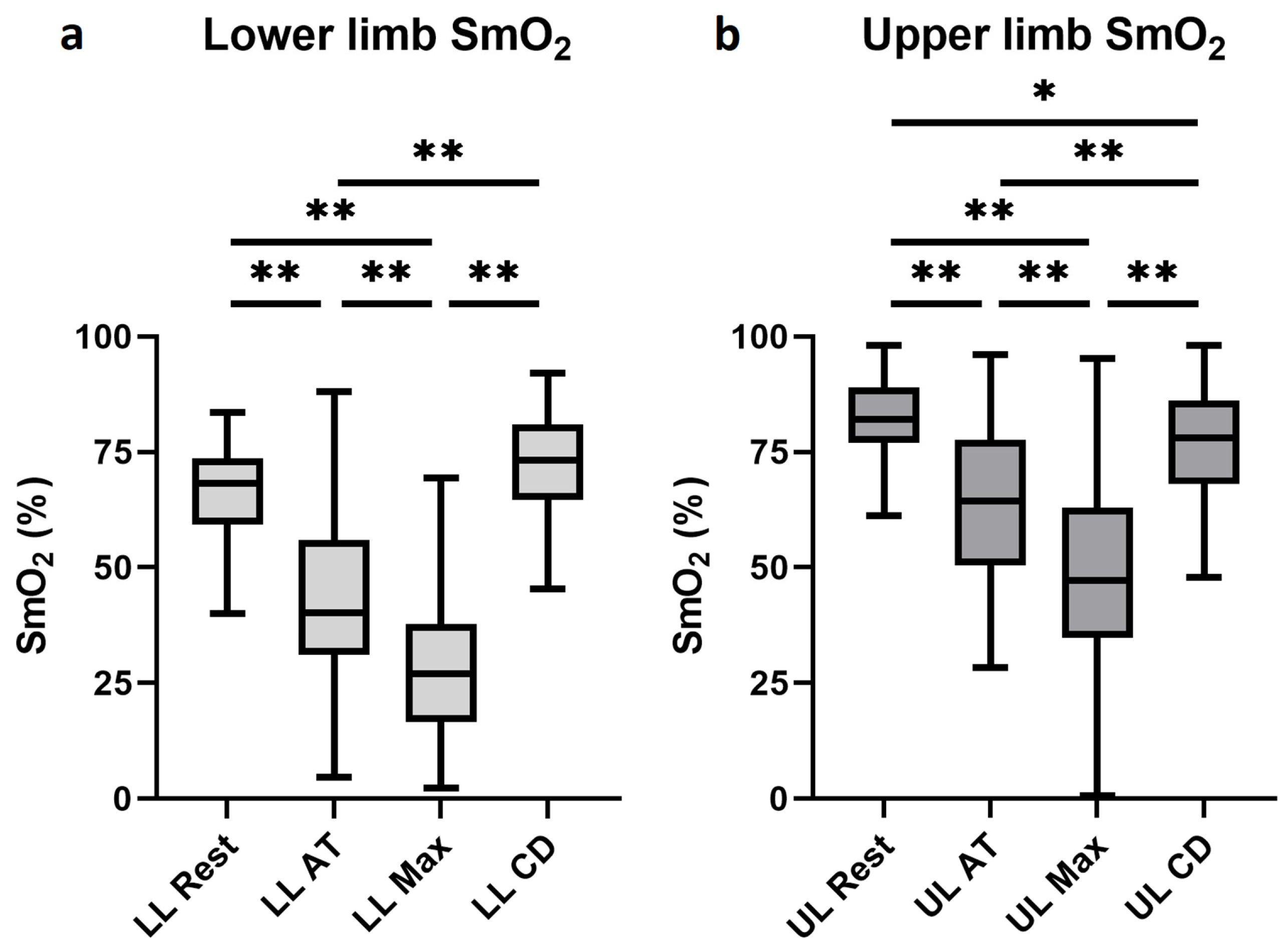

3.4. Differences Between the Muscle Oxygen Saturation of the Upper and Lower Extremities

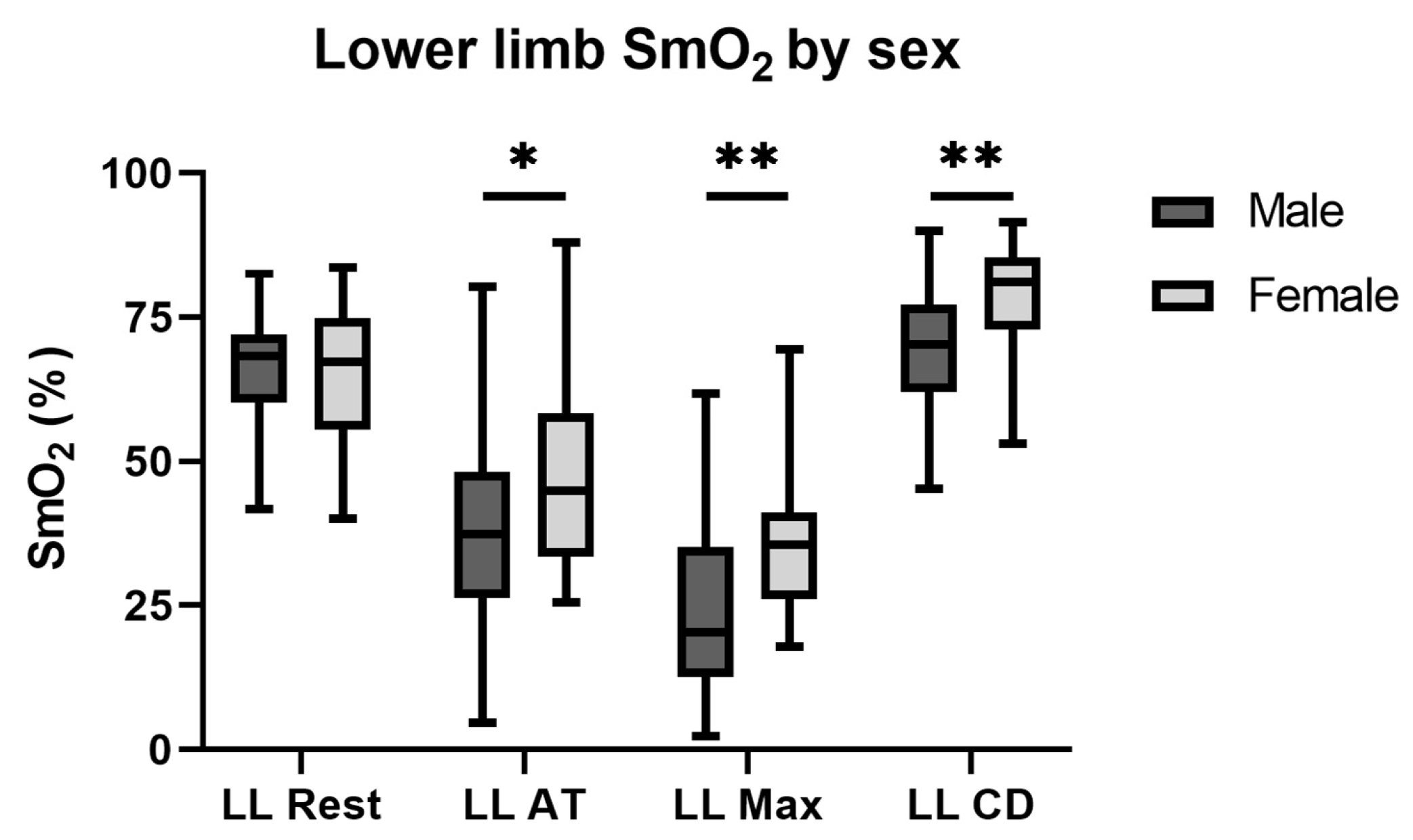

3.5. Sex Differences in Muscle Oxygen Saturation Measurements

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison Between the Upper and Lower Extremity SmO2 Measurements

4.2. SmO2 Value Changes Regarding the Sexes

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Hb | hemoglobin |

| Mb | myoglobin |

| SmO2 | mixed muscle tissue oxygen saturation |

| CPET | cardiopulmonary exercise testing |

| RER | respiratory exchange ratio |

| IQR | interquartile range |

References

- Corrado, D.; Zorzi, A.; Basso, C.; Thiene, G. 800 years of research at the University of Padua (1222–2022): Contemporary insights into Sports Cardiology. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 1787–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Gerche, A.; Baggish, A.; Heidbuchel, H.; Levine, B.D.; Rakhit, D. What May the Future Hold for Sports Cardiology? Heart Lung Circ. 2018, 27, 1116–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, M.W.; Kim, J.H.; Shah, A.B.; Phelan, D.; Emery, M.S.; Wasfy, M.M.; Fernandez, A.B.; Bunch, T.J.; Dean, P.; Danielian, A.; et al. Exercise-Induced Cardiovascular Adaptations and Approach to Exercise and Cardiovascular Disease: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 78, 1453–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakatos, B.K.; Molnar, A.A.; Kiss, O.; Sydo, N.; Tokodi, M.; Solymossi, B.; Fabian, A.; Dohy, Z.; Vago, H.; Babity, M.; et al. Relationship between Cardiac Remodeling and Exercise Capacity in Elite Athletes: Incremental Value of Left Atrial Morphology and Function Assessed by Three-Dimensional Echocardiography. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2020, 33, 101–109.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabian, A.; Lakatos, B.K.; Tokodi, M.; Kiss, A.R.; Sydo, N.; Csulak, E.; Kispal, E.; Babity, M.; Szucs, A.; Kiss, O.; et al. Geometrical remodeling of the mitral and tricuspid annuli in response to exercise training: A 3-D echocardiographic study in elite athletes. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2021, 320, H1774–H1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.M.; Carter, H. The effect of endurance training on parameters of aerobic fitness. Sports Med. 2000, 29, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakatos, B.K.; Kiss, O.; Tokodi, M.; Tősér, Z.; Sydó, N.; Merkely, G.; Babity, M.; Szilágyi, M.; Komócsin, Z.; Bognár, C.; et al. Exercise-induced shift in right ventricular contraction pattern: Novel marker of athlete’s heart? Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2018, 315, H1640–H1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, P.U.; Pyne, D.B.; Telford, R.D.; Hawley, J.A. Factors affecting running economy in trained distance runners. Sports Med. 2004, 34, 465–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabian, A.; Ujvari, A.; Tokodi, M.; Lakatos, B.K.; Kiss, O.; Babity, M.; Zamodics, M.; Sydo, N.; Csulak, E.; Vago, H.; et al. Biventricular mechanical pattern of the athlete’s heart: Comprehensive characterization using three-dimensional echocardiography. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2022, 29, 1594–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazic, S.; Lazovic, B.; Djelic, M.; Suzic-Lazic, J.; Djordjevic-Saranovic, S.; Durmic, T.; Soldatovic, I.; Zikic, D.; Gluvic, Z.; Zugic, V. Respiratory parameters in elite athletes—Does sport have an influence? Rev. Port. Pneumol. 2015, 21, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mairbaurl, H. Red blood cells in sports: Effects of exercise and training on oxygen supply by red blood cells. Front. Physiol. 2013, 4, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mairbaurl, H. Red blood cell function in hypoxia at altitude and exercise. Int. J. Sports Med. 1994, 15, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, R.A.; Lundby, C. Mitochondria express enhanced quality as well as quantity in association with aerobic fitness across recreationally active individuals up to elite athletes. J. Appl. Physiol. 2013, 114, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldmann, A.; Schmitz, R.; Erlacher, D. Near-infrared spectroscopy-derived muscle oxygen saturation on a 0% to 100% scale: Reliability and validity of the Moxy Monitor. J. Biomed. Opt. 2019, 24, 115001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, M.L.; Barstow, T.J. Estimated contribution of hemoglobin and myoglobin to near infrared spectroscopy. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2013, 186, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barstow, T.J. Understanding near infrared spectroscopy and its application to skeletal muscle research. J. Appl. Physiol. 2019, 126, 1360–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloniger, M.A.; Cureton, K.J.; Prior, B.M.; Evans, E.M. Lower extremity muscle activation during horizontal and uphill running. J. Appl. Physiol. 1997, 83, 2073–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, A.K.A.; Stellingwerff, T.; Smith, E.S.; Martin, D.T.; Mujika, I.; Goosey-Tolfrey, V.L.; Sheppard, J.; Burke, L.M. Defining Training and Performance Caliber: A Participant Classification Framework. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2022, 17, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, G.F.; Balady, G.J.; Amsterdam, E.A.; Chaitman, B.; Eckel, R.; Fleg, J.; Froelicher, V.F.; Leon, A.S.; Pina, I.L.; Rodney, R.; et al. Exercise standards for testing and training: A statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2001, 104, 1694–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, R.J.; Balady, G.J.; Beasley, J.W.; Bricker, J.T.; Duvernoy, W.F.; Froelicher, V.F.; Mark, D.B.; Marwick, T.H.; McCallister, B.D.; Thompson, P.D., Jr.; et al. ACC/AHA Guidelines for Exercise Testing. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on Exercise Testing). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1997, 30, 260–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, K.; Whipp, B.J.; Koyl, S.N.; Beaver, W.L. Anaerobic threshold and respiratory gas exchange during exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 1973, 35, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crum, E.M.; O’Connor, W.J.; Van Loo, L.; Valckx, M.; Stannard, S.R. Validity and reliability of the Moxy oxygen monitor during incremental cycling exercise. Eur. J. Sport. Sci. 2017, 17, 1037–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermens, H.J.; Freriks, B.; Disselhorst-Klug, C.; Rau, G. Development of recommendations for SEMG sensors and sensor placement procedures. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2000, 10, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yogev, A.; Arnold, J.; Clarke, D.; Guenette, J.A.; Sporer, B.C.; Koehle, M.S. Comparing the Respiratory Compensation Point with Muscle Oxygen Saturation in Locomotor and Non-locomotor Muscles Using Wearable NIRS Spectroscopy During Whole-Body Exercise. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 818733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Hooff, M.; Meijer, E.J.; Scheltinga, M.R.M.; Savelberg, H.; Schep, G. Test-retest reliability of skeletal muscle oxygenation measurement using near-infrared spectroscopy during exercise in patients with sport-related iliac artery flow limitation. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging 2022, 42, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitada, T.; Machida, S.; Naito, H. Influence of muscle fibre composition on muscle oxygenation during maximal running. BMJ Open Sport. Exerc. Med. 2015, 1, e000062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalliokoski, K.K.; Oikonen, V.; Takala, T.O.; Sipila, H.; Knuuti, J.; Nuutila, P. Enhanced oxygen extraction and reduced flow heterogeneity in exercising muscle in endurance-trained men. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 280, E1015–E1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda-Fuentes, C.; Guisado-Requena, I.M.; Delgado-Floody, P.; Arias-Poblete, L.; Perez-Castilla, A.; Jerez-Mayorga, D.; Chirosa-Rios, L.J. Reliability of Low-Cost Near-Infrared Spectroscopy in the Determination of Muscular Oxygen Saturation and Hemoglobin Concentration during Rest, Isometric and Dynamic Strength Activity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda-Fuentes, C.; Chirosa-Rios, L.J.; Guisado-Requena, I.M.; Delgado-Floody, P.; Jerez-Mayorga, D. Changes in Muscle Oxygen Saturation Measured Using Wireless Near-Infrared Spectroscopy in Resistance Training: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangsbo, J.; Hellsten, Y. Muscle blood flow and oxygen uptake in recovery from exercise. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1998, 162, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellinger, J.R.; Figueroa, A.; Gonzales, J.U. Reactive hyperemia half-time response is associated with skeletal muscle oxygen saturation changes during cycling exercise. Microvasc. Res. 2023, 149, 104569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendra-Perez, C.; Sanchez-Jimenez, J.L.; Marzano-Felisatti, J.M.; Encarnacion-Martinez, A.; Salvador-Palmer, R.; Priego-Quesada, J.I. Reliability of threshold determination using portable muscle oxygenation monitors during exercise testing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmani, F.; Lago-Fuentes, C.; Alemany-Iturriaga, J.; Barcala-Furelos, M. The relationship of muscle oxygen saturation analyzer with other monitoring and quantification tools in a maximal incremental treadmill test. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1155037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Arenas, S.; Quero-Calero, C.D.; Abellan-Aynes, O.; Andreu-Caravaca, L.; Fernandez-Calero, M.; Manonelles, P.; Lopez-Plaza, D. Assessment of Intercostal Muscle Near-Infrared Spectroscopy for Estimating Respiratory Compensation Point in Trained Endurance Athletes. Sports 2023, 11, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiroyuki, H.; Hamaoka, T.; Sako, T.; Nishio, S.; Kime, R.; Murakami, M.; Katsumura, T. Oxygenation in vastus lateralis and lateral head of gastrocnemius during treadmill walking and running in humans. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2002, 87, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Briceno, F.; Espinosa-Ramirez, M.; Hevia, G.; Llambias, D.; Carrasco, M.; Cerda, F.; Lopez-Fuenzalida, A.; Garcia, P.; Gabrielli, L.; Viscor, G. Reliability of NIRS portable device for measuring intercostal muscles oxygenation during exercise. J. Sports Sci. 2019, 37, 2653–2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Born, D.P.; Stoggl, T.; Swaren, M.; Bjorklund, G. Near-Infrared Spectroscopy: More Accurate Than Heart Rate for Monitoring Intensity in Running in Hilly Terrain. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2017, 12, 440–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santarem, D.; Machado, I.; Sampaio, J.; Abrantes, C. Comparing the effects of dynamic and holding isometric contractions on cardiovascular, perceptual, and near-infrared spectroscopy parameters: A pilot study. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0281885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Hu, W.; Ma, Y.; Xiang, H. Machine learning prediction of pulmonary oxygen uptake from muscle oxygen in cycling. J. Sports Sci. 2024, 42, 1299–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, K.G.; Daigle, K.A.; Patterson, P.; Cowman, J.; Chelland, S.; Haymes, E.M. Reliability of near-infrared spectroscopy for determining muscle oxygen saturation during exercise. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport. 2005, 76, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalamitros, A.A.; Semaltianou, E.; Toubekis, A.G.; Kabasakalis, A. Muscle Oxygenation, Heart Rate, and Blood Lactate Concentration During Submaximal and Maximal Interval Swimming. Front. Sports Act. Living 2021, 3, 759925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benincasa, M.T.; Serra, E.; Albano, D.; Vastola, R. Comparing muscle oxygen saturation patterns in swimmers of different competitive levels. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2024, 24, 192–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoggl, T.; Born, D.P. Near Infrared Spectroscopy for Muscle Specific Analysis of Intensity and Fatigue during Cross-Country Skiing Competition-A Case Report. Sensors 2021, 21, 2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hesford, C.M.; Laing, S.; Cooper, C.E. Using portable NIRS to compare arm and leg muscle oxygenation during roller skiing in biathletes: A case study. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2013, 789, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, B.; Cooper, C.E. Underwater Near-Infrared Spectroscopy: Muscle Oxygen Changes in the Upper and Lower Extremities in Club Level Swimmers and Triathletes. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2016, 876, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Ramirez, M.; Moya-Gallardo, E.; Araya-Roman, F.; Riquelme-Sanchez, S.; Rodriguez-Garcia, G.; Reid, W.D.; Viscor, G.; Araneda, O.F.; Gabrielli, L.; Contreras-Briceno, F. Sex-Differences in the Oxygenation Levels of Intercostal and Vastus Lateralis Muscles During Incremental Exercise. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 738063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sendra-Perez, C.; Priego-Quesada, J.I.; Salvador-Palmer, R.; Murias, J.M.; Encarnacion-Martinez, A. Sex-related differences in profiles of muscle oxygen saturation of different muscles in trained cyclists during graded cycling exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 2023, 135, 1092–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, B.A.; Smithmyer, S.L.; Pelberg, J.A.; Mishkin, A.D.; Herr, M.D.; Proctor, D.N. Sex differences in leg vasodilation during graded knee extensor exercise in young adults. J. Appl. Physiol. 2007, 103, 1583–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J.; Sheriff, D.D. Role of estrogen in nitric oxide- and prostaglandin-dependent modulation of vascular conductance during treadmill locomotion in rats. J. Appl. Physiol. 2004, 97, 756–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| All Players | Male | Female | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant [n] (%)] | 100 (100%) | 63 (63%) | 37 (37%) | - |

| Age [year] | 17.2 (16.1–18.9) | 17.6 (16.2–19.0) | 17.0 (15.1–18.6) | 0.237 |

| Training [h/week] | 17.5 (15.0–21.0) | 17.5 (15.0–21.0) | 17.5 (14.5–22.9) | 0.816 |

| Height [cm] | 183.0 (173.8–189.3) | 187.0 (183.0–193.0) | 173.0 (171.0–178.0) | 0.001 |

| Weight [kg] | 77.0 (70.0–88.0) | 83.0 (75.5–92.0) | 72.0 (67.0–77.0) | 0.001 |

| BMI [kg/m2] | 23.5 (22.1–25.3) | 23.4 (22.2–25.7) | 23.7 (22.1–25.1) | 0.631 |

| Left Vastus Lateralis | Right Vastus Lateralis | Average of Left and Right Vastus Lateralis | Left Deltoid Muscle | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rest [%] | 65.0 (57.1–72.0) | 70.1 (59.2–77.6) | 68.3 (59.2–73.6) | 82.1 (77.0–89.0) | <0.001 |

| Anaerobic threshold [%] | 39.0 (29.0–54.0) | 40.0 (29.6–56.6) | 40.2 (31.1–56.0) | 64.3 (50.4–77.7) | <0.001 |

| Maximal intensity [%] | 27.0 (17.1–36.6) | 25.9 (15.7–40.0) | 27.0 (16.6–37.7) | 47.2 (34.7–62.9) | <0.001 |

| 5 min cool-down [%] | 71.8 (61.4–78.0) | 77.1 (65.0–83.1) | 73.3 (64.7–80.9) | 78.0 (68.0–86.1) | 0.003 |

| Male | Female | p | Relative Changes Male | Relative Changes Female | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Averaged lower extremities | ||||||

| Rest | 68.3% (60.2–72.0%) | 67.2% (55.5–74.9%) | 0.960 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Anaerobic threshold | 37.4% (26.3–48.2%) | 44.9% (33.6–58.4%) | 0.024 | −0.441 (−0.635–−0.229) | −0.291 (−0.411–−0.177) | 0.003 |

| Maximal intensity | 20.3% (12.6–35.2%) | 35.5% (26.1–41.1%) | <0.001 | −0.669 (−0.808–−0.469) | −0.457 (−0.549–−0.358) | <0.001 |

| 5 min cool-down | 70.3% (62.0–77.2%) | 78.3% (72.0–85.0%) | <0.001 | +0.022 (−0.090–+0.127) | +0.164 (+1.023–+0.291) | <0.001 |

| Upper extremity | ||||||

| Rest | 80.0% (74.0–84.0%) | 87.8% (83.0–92.0%) | <0.001 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Anaerobic threshold | 56.4% (48.2–72.0%) | 73.8% (57.8–82.6%) | 0.007 | −0.245 (−0.345–−0.111) | −0.176 (−0.319–−0.055) | 0.268 |

| Maximal intensity | 41.3% (31.2–56.1%) | 53.6% (40.2–68.8%) | 0.009 | −0.444 (−0.572–−0.298) | −0.374 (−0.543–−0.200) | 0.127 |

| 5 min cool-down | 73.1% (63.6–80.2%) | 86.0% (78.0–94.4%) | <0.001 | −0.076 (−0.165–−0.011) | −0.011 (−0.077–+0.007) | 0.009 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Babity, M.; Zámodics, M.; Kovács, É.; Bucskó-Varga, Á.; Kulcsár, P.; Boroncsok, D.; Benkő, R.; Fábián, A.; Horváth, M.; Balla, D.; et al. Monitoring Treadmill Physical Exercise and Recovery in Elite Water Polo Players with Local Muscle Oxygen Saturation Measurements—Regional and Sex Differences. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040464

Babity M, Zámodics M, Kovács É, Bucskó-Varga Á, Kulcsár P, Boroncsok D, Benkő R, Fábián A, Horváth M, Balla D, et al. Monitoring Treadmill Physical Exercise and Recovery in Elite Water Polo Players with Local Muscle Oxygen Saturation Measurements—Regional and Sex Differences. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2025; 10(4):464. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040464

Chicago/Turabian StyleBabity, Máté, Márk Zámodics, Éva Kovács, Ágnes Bucskó-Varga, Panka Kulcsár, Dóra Boroncsok, Regina Benkő, Alexandra Fábián, Márton Horváth, Dorottya Balla, and et al. 2025. "Monitoring Treadmill Physical Exercise and Recovery in Elite Water Polo Players with Local Muscle Oxygen Saturation Measurements—Regional and Sex Differences" Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 10, no. 4: 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040464

APA StyleBabity, M., Zámodics, M., Kovács, É., Bucskó-Varga, Á., Kulcsár, P., Boroncsok, D., Benkő, R., Fábián, A., Horváth, M., Balla, D., Lakatos, B. K., Kovács, A., Vágó, H., Merkely, B., & Kiss, O. (2025). Monitoring Treadmill Physical Exercise and Recovery in Elite Water Polo Players with Local Muscle Oxygen Saturation Measurements—Regional and Sex Differences. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 10(4), 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040464