Effects of Pilates Matwork Core Exercises on Functioning in Middle-Aged Adult Women with Chronic Nonspecific Low Back Pain Through Flexion Relaxation Phenomenon Analysis: A Pilot RCT

Abstract

1. Introduction

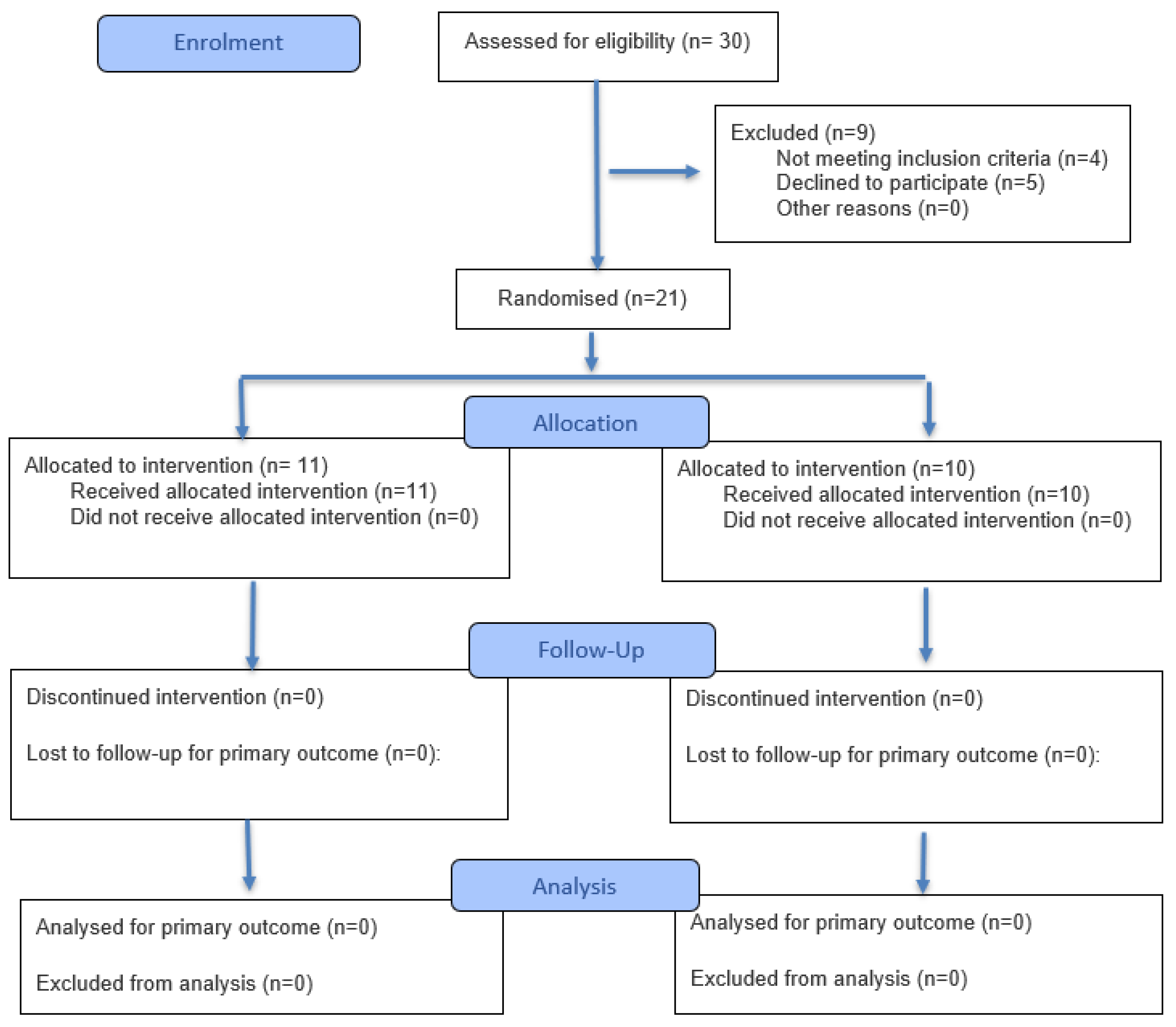

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Intervention

2.3. The Experimental 8-Pilates Matwork Exercise Program [22,23,24]

- “Spine stretch”: The subjects began in a seated position at a 90-degree angle, with legs extended forward, shoulder-width apart, feet in a hammer position, arms extended parallel to the legs and the ground. The participants inhaled to prepare for the movement. During exhalation, they bent their torso forward, trying to bring their navel towards the spine through abdominal contraction, lowering their head towards their knees with arms extended in front of the body trying to form a C with the spine. Once at the point of maximum flexion, we recommended inhaling to prepare for the return. Exhaling, the subject returned to the starting position, realigning the spine with the hips.

- “Spine twist”: The participants started from a seated position at a 90-degree angle, with legs spread out extended forward, feet in a hammer position, arms abducted at 90°, externally rotated and shoulders away from the ear. Before starting with the trunk rotation, it was important to lengthen the spine upwards even more. The participant began with the trunk rotation exhaling, bringing one upper limb backward, with the head following the movement of the hand stretching back, without moving the pelvis or body weight and performing a dorsal twist, ten times per side.

- “Hundred”: Starting from a supine position, the subject raised his legs and bent his knees at 90°, keeping the abdomen contracted and the navel towards the spine. The spine was necessary to adhere to the ground as much as possible. The participant bent his torso forward until the lower angle of the scapula touched the ground, then the arms were detached from the ground, keeping them with the palm facing down for two inhalations, then, the palm of the hand was rotated upwards to perform two exhalations. Swing the arms energetically and in a coordinated way with the breathing rhythm.

- “Leg changes”: the subject started from a supine position, keeping the abdomen and pelvis in a neutral position, with arms along the trunk and palms of the hands on the floor. The hips were bent, bringing the thighs towards the abdomen. The participant had to inhale to prepare for the movement, further stabilizing the pelvis. Subsequently, it was necessary for the subject to exhale bringing one leg towards the abdomen, trying to adhere to the ground with the lumbar area, then, instead of inhaling, going to touch the ground with the foot and return to the starting position. It was essential to alternate the movement with both legs, performing ten repetitions per leg. The same exercise could be performed keeping both feet raised, in the same position as the Hundred exercise, alternating the movement of the legs bringing the foot to the ground.

- “Roll up”: The subject began lying on their back with legs slightly spread and arms extended behind their head. They inhaled to prepare for the movement. They exhaled, lifting their arms, head, and back, slowly lifting off the mat one vertebra at a time, “unrolling” the spine, to engage the core and pull the navel in. Once in a seated position at 90°, the participant was instructed to inhale and, exhaling, bend the torso over the thighs (as in the Spine stretch exercise). At the point of maximum flexion, they also inhaled and, exhaling, returned to the starting position, slowly resting on the ground one vertebra at a time.

- “Pelvic curl”: Starting position lying on their back with knees bent and feet flat on the ground. The participant aligned their nose with their navel and stabilized the pelvis. They kept the spine in a neutral position, inhaled to prepare for the movement, and exhaled while contracting the abdomen, bringing the navel towards the spine and trying to flatten the lumbar curve, making the spine completely adhere to the mat. They were recommended to inhale while maintaining the position, then exhale and relax the muscles, returning the spine to neutral, recreating the lumbar lordosis.

- “Shoulder bridge”: lying on their back with knees bent and feet flat on the ground, to align the nose with the navel and stabilize the pelvis. It was necessary to inhale to prepare for the movement; exhaling, they lifted the pelvis and then the spine from the mat, trying to “unroll” the spine from the ground, vertebra by vertebra. Once in the final position, the patient had to inhale contracting the glutes. Exhaling, return to the starting position, making the spine adhere to the ground one vertebra at a time.

- “Leg circles”: The patients started lying on their back, bending the hip at 90°. The knee of the flexed hip remained completely extended, then, the participant was instructed to draw a circle with the extended leg, starting the movement from the hip, activating the core and trying to keep the rest of the body still. For each gesture performed, they inhaled, and exhaled with the next. Ten repetitions clockwise and ten counterclockwise. Then, repeat the exercise with the other leg.

2.4. Outcome Measures

- -

- The Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) is a self-administered questionnaire used to measure pain and disability in patients with chronic low back pain (LBP). It takes a few minutes to complete and is divided into ten sections that assess how LBP affects different aspects of daily life, such as pain intensity, personal hygiene, lifting weights, walking, sitting, standing, sleeping, sex life, social life, and traveling. Each section has six response options, with scores ranging from 0 to 5, where 0 represents no difficulty or pain and 5 represents inability to perform the activity or disabling pain. The ODI produces a final functional score ranging from 0 to 100, interpreted as follows: 0–20% minimal disability without therapy needed; 20–40% moderate disability requiring conservative therapy; 40–60% severe disability requiring further examination; 60–80% devastating disability requiring substantial intervention and bedridden.

- -

- The Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale (QBPDS) is a self-assessment tool developed in 1995 to assess disability related to low back pain. It consists of 20 items that measure an individual’s ability to perform various daily activities, including walking, sitting, lifting objects, and bending. Each item has six possible responses, with scores from 0 to 5, where 0 indicates no difficulty and 5 indicates severe disability. The total score ranges from 0 (no difficulty) to 100 (maximum disability). The score is classified as follows: 0/20% no or mild disability; 21/40% moderate disability; 41/60% severe disability; 61/80% very severe disability; 81/100% extremely severe disability.

- -

- NRS: This is a unidimensional, quantitative, 11-point numerical rating scale for assessing and quantifying pain. The scale requires the operator to ask the patient to select the number that best describes the intensity of their pain, from 0 to 10, at that precise moment. The patient is asked: “If 0 represents no pain and 10 represents the worst possible pain, what is the pain you are experiencing now?”

- -

- Relaxation/Flexion Phenomenon assessment: The forward bending/extension movement of the torso was evaluated while the patient stood upright. The patient was instructed to move in response to a verbal command, keeping their knees straight but not locked and their arms hanging freely. They were asked to slowly bend forward to full flexion over 3 s, pause for 3 s at full flexion, and then return to the starting upright position over 3 s. This movement was performed three times, and the average of the tests was used in the analysis. Before the first test, patients practiced the assessment to become familiar with the movement. Surface electromyography was used to assess muscle activation. A four-channel conditioning module (BTS FREEEMG 1000) with a common mode rejection ratio greater than 100 dB and a 20–450 Hz band-pass filter amplified the signal 2000 times using a sampling frequency of 1 kHz and wireless transmission. The signals were captured using self-adhesive, single-use Ag/AgCl surface electrodes, 1 cm in diameter. After cleaning the skin with 70% alcohol, the electrodes were placed 2 cm apart, center to center, on the paravertebral muscles at the level of L1–L2 and on the multifidus muscles at the level of the L4-L5 vertebrae on each side. The electrodes were placed with a vertical distance of about 1 cm between their edges while the trunk was in a semi-flexed position. The EMG signal was collected during this motion, and a flexion–relaxation ratio (FRR) was calculated using the approach of Ritvanen et al. [25]. The FRR was calculated as the ratio between the RMS activity during trunk flexion and the RMS activity during full flexion. In this scenario, EMG activity was high during full flexion, which is typical among patients with LBP; conversely, the presence of a flexion–relaxation phenomenon indicates myoelectric silence in full flexion.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, J.; Jiang, N.; Xu, H.; Wu, Y.; Cheng, S.; Liang, B. Efficacy of Cognitive Functional Therapy in Patients with Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2024, 151, 104679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tulder, M.; Becker, A.; Bekkering, T.; Breen, A.; Del Real, M.T.G.; Hutchinson, A.; Koes, B.; Laerum, E.; Malmivaara, A.; On behalf of the COST B13 Working Group on Guidelines for the Management of Acute Low Back Pain in Primary Care. Chapter 3 European Guidelines for the Management of Acute Nonspecific Low Back Pain in Primary Care. Eur. Spine J. 2006, 15, s169–s191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eliks, M.; Zgorzalewicz-Stachowiak, M.; Zeńczak-Praga, K. Application of Pilates-Based Exercises in the Treatment of Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain: State of the Art. Postgrad. Med. J. 2019, 95, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyamoto, G.C.; Costa, L.O.P.; Galvanin, T.; Cabral, C.M.N. The Efficacy of the Addition of the Pilates Method over a Minimal Intervention in the Treatment of Chronic Nonspecific Low Back Pain: A Study Protocol of a Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Chiropr. Med. 2011, 10, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Knezevic, N.N.; Candido, K.D.; Vlaeyen, J.W.S.; Van Zundert, J.; Cohen, S.P. Low Back Pain. Lancet 2021, 398, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, J.A.; Ellis, J.; Ogilvie, R.; Malmivaara, A.; Van Tulder, M.W. Exercise Therapy for Chronic Low Back Pain. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 2021, CD009790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, J.; Furlan, A.D.; Lam, W.Y.; Hsu, M.Y.; Ning, Z.; Lao, L. Acupuncture for Chronic Nonspecific Low Back Pain. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 2020, CD013814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Tang, C.; Yin, L.; Jiang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Chen, C. Clinical and omics biomarkers in osteoarthritis diagnosis and treatment. J. Orthop. Translat. 2025, 50, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaina, F.; Côté, P.; Cancelliere, C.; Di Felice, F.; Donzelli, S.; Rauch, A.; Verville, L.; Negrini, S.; Nordin, M. A Systematic Review of Clinical Practice Guidelines for Persons with Non-Specific Low Back Pain with and without Radiculopathy: Identification of Best Evidence for Rehabilitation to Develop the WHO’s Package of Interventions for Rehabilitation. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2023, 104, 1913–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernetti, A.; La Russa, R.; De Sire, A.; Agostini, F.; De Simone, S.; Farì, G.; Lacasella, G.V.; Santilli, G.; De Trane, S.; Karaboue, M.; et al. Cervical Spine Manipulations: Role of Diagnostic Procedures, Effectiveness, and Safety from a Rehabilitation and Forensic Medicine Perspective: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sire, A.; Lippi, L.; Calafiore, D.; Marotta, N.; Mezian, K.; Chiaramonte, R.; Cisari, C.; Vecchio, M.; Ammendolia, A.; Invernizzi, M. Dynamic Spinal Orthoses Self-Reported Effects in Patients with Back Pain Due to Vertebral Fragility Fractures: A Multi-Center Prospective Cohort Study. J. Back. Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 2024, 37, 929–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, A.-C.; Pfeifer-Schröder, P.; Schiltenwolf, M.; Vogt, L.; Schneider, C.; Platen, P.; Beck, H.; Wippert, P.-M.; Engel, T.; Wochatz, M.; et al. Finding Predictive Factors of Exercise Adherence in Randomized Controlled Trials on Low Back Pain: An Individual Data Re-Analysis Using Machine Learning Techniques. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2025, 106, 738–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boudier-Revéret, M.; Thu, A.C.; Hsiao, M.Y.; Shyu, S.G.; Chang, M.C. The Effectiveness of Pulsed Radiofrequency on Joint Pain: A Narrative Review. Pain. Pract. 2020, 20, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Rodríguez, R.; Álvarez-Bueno, C.; Cavero-Redondo, I.; Torres-Costoso, A.; Pozuelo-Carrascosa, D.P.; Reina-Gutiérrez, S.; Pascual-Morena, C.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V. Best Exercise Options for Reducing Pain and Disability in Adults with Chronic Low Back Pain: Pilates, Strength, Core-Based, and Mind-Body. A Network Meta-Analysis. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2022, 52, 505–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouteron, A.; Tabard-Fougère, A.; Moissenet, F.; Bourredjem, A.; Rose-Dulcina, K.; Genevay, S.; Laroche, D.; Armand, S. Sensitivity and Specificity of the Flexion and Extension Relaxation Ratios to Identify Altered Paraspinal Muscles’ Flexion Relaxation Phenomenon in Nonspecific Chronic Low Back Pain Patients. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2023, 68, 102740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisser, M.E.; Ranavaya, M.; Haig, A.J.; Roth, R.S.; Zucker, R.; Ambroz, C.; Caruso, M. A Meta-Analytic Review of Surface Electromyography Among Persons with Low Back Pain and Normal, Healthy Controls. J. Pain. 2005, 6, 711–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claus, A.P.; Hides, J.A.; Moseley, G.L.; Hodges, P.W. Different ways to balance the spine: Subtle changes in sagittal spinal curves affect regional muscle activity. Spine 2009, 34, E208–E214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marotta, N.; De Sire, A.; Lippi, L.; Moggio, L.; Tasselli, A.; Invernizzi, M.; Ammendolia, A.; Iona, T. Impact of Yoga Asanas on Flexion and Relaxation Phenomenon in Women with Chronic Low Back Pain: Prophet Model Prospective Study. J. Orthop. Res. 2024, 42, 1420–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuddy, P.; Gaskell, L. “How Do Pilates Trained Physiotherapists Utilize and Value Pilates Exercise for MSK Conditions? A Qualitative Study”. Musculoskelet. Care 2020, 18, 315–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tottoli, C.R.; Ben, Â.J.; Da Silva, E.N.; Bosmans, J.E.; Van Tulder, M.; Carregaro, R.L. Effectiveness of Pilates Compared with Home-Based Exercises in Individuals with Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain: Randomised Controlled Trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2024, 38, 1495–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajswelner, H.; Metcalf, B.; Bennell, K. Clinical Pilates versus General Exercise for Chronic Low Back Pain: Randomized Trial. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2012, 44, 1197–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greco, F.; Tarsitano, M.G.; Cosco, L.F.; Quinzi, F.; Folino, K.; Spadafora, M.; Afzal, M.; Segura-Garcia, C.; Maurotti, S.; Pujia, R.; et al. The Effects of Online Home-Based Pilates Combined with Diet on Body Composition in Women Affected by Obesity: A Preliminary Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaras, N.; Kavvoura, A.; Gerolemou, S.; Hadjicharalambous, M. Pilates-Mat Training and Detraining: Effects on Body Composition and Physical Fitness in Pilates-Trained Women. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2023, 36, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cakmakçi, O. The Effect of 8 Week Pilates Exercise on Body Composition in Obese Women. Coll. Antropol. 2011, 35, 1045–1050. [Google Scholar]

- Ritvanen, T.; Zaproudina, N.; Nissen, M.; Leinonen, V.; Hänninen, O. Dynamic Surface Electromyographic Responses in Chronic Low Back Pain Treated by Traditional Bone Setting and Conventional Physical Therapy. J. Manipulative Physiol. Ther. 2007, 30, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neblett, R.; Brede, E.; Mayer, T.G.; Gatchel, R.J. What Is the Best Surface EMG Measure of Lumbar Flexion-Relaxation for Distinguishing Chronic Low Back Pain Patients From Pain-Free Controls? Clin. J. Pain. 2013, 29, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.M.; Obara, K.; Dias, J.M.; Menacho, M.O.; Guariglia, D.A.; Schiavoni, D.; Pereira, H.M.; Cardoso, J.R. Comparing the Pilates Method with No Exercise or Lumbar Stabilization for Pain and Functionality in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Rehabil. 2012, 26, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neblett, R.; Mayer, T.G.; Gatchel, R.J.; Keeley, J.; Proctor, T.; Anagnostis, C. Quantifying the Lumbar Flexion–Relaxation Phenomenon: Theory, Normative Data, and Clinical Applications. Spine 2003, 28, 1435–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouteron, A.; Tabard-Fougère, A.; Bourredjem, A.; Casillas, J.-M.; Armand, S.; Genevay, S. The Flexion Relaxation Phenomenon in Nonspecific Chronic Low Back Pain: Prevalence, Reproducibility and Flexion–Extension Ratios. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. Spine J. 2022, 31, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, M.W.; Li, L.; Solomonow, M. Flexion-Relaxation Response to Cyclic Lumbar Flexion. Clin. Biomech. 2004, 19, 769–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taulaniemi, A.; Kankaanpää, M.; Tokola, K.; Parkkari, J.; Suni, J.H. Neuromuscular Exercise Reduces Low Back Pain Intensity and Improves Physical Functioning in Nursing Duties among Female Healthcare Workers; Secondary Analysis of a Randomised Controlled Trial. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2019, 20, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marotta, N.; De Sire, A.; Bartalotta, I.; Sgro, M.; Zito, R.; Invernizzi, M.; Ammendolia, A.; Iona, T. Role of the Flexion Relaxation Phenomenon in the Analysis of Low Back Pain Risk in the Powerlifter: A Proof-of-Principle Study. J. Sport. Rehabil. 2024, 33, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostini, F.; De Sire, A.; Furcas, L.; Finamore, N.; Farì, G.; Giuliani, S.; Sveva, V.; Bernetti, A.; Paoloni, M.; Mangone, M. Postural Analysis Using Rasterstereography and Inertial Measurement Units in Volleyball Players: Different Roles as Indicators of Injury Predisposition. Medicina 2023, 59, 2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phrompaet, S.; Paungmali, A.; Pirunsan, U.; Sitilertpisan, P. Effects of Pilates Training on Lumbo-Pelvic Stability and Flexibility. Asian J. Sports Med. 2011, 2, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercurio, M.; Familiari, F.; de Filippis, R.; Varano, C.; Napoleone, F.; Galasso, O.; Gasparini, G. Improvement in Health Status and Quality of Life in Patients with Osteoporosis Treated with Denosumab: Results at a Mean Follow-up of Six Years. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 26, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Filippis, R.; Mercurio, M.; Spina, G.; De Fazio, P.; Segura-Garcia, C.; Familiari, F.; Gasparini, G.; Galasso, O. Antidepressants and Vertebral and Hip Risk Fracture: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2022, 10, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercurio, M.; Castioni, D.; de Filippis, R.; De Fazio, P.; Paone, A.; Familiari, F.; Gasparini, G.; Galasso, O. Postoperative Psychological Factors and Quality of Life but Not Shoulder Brace Adherence Affect Clinical Outcomes after Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2023, 32, 1953–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

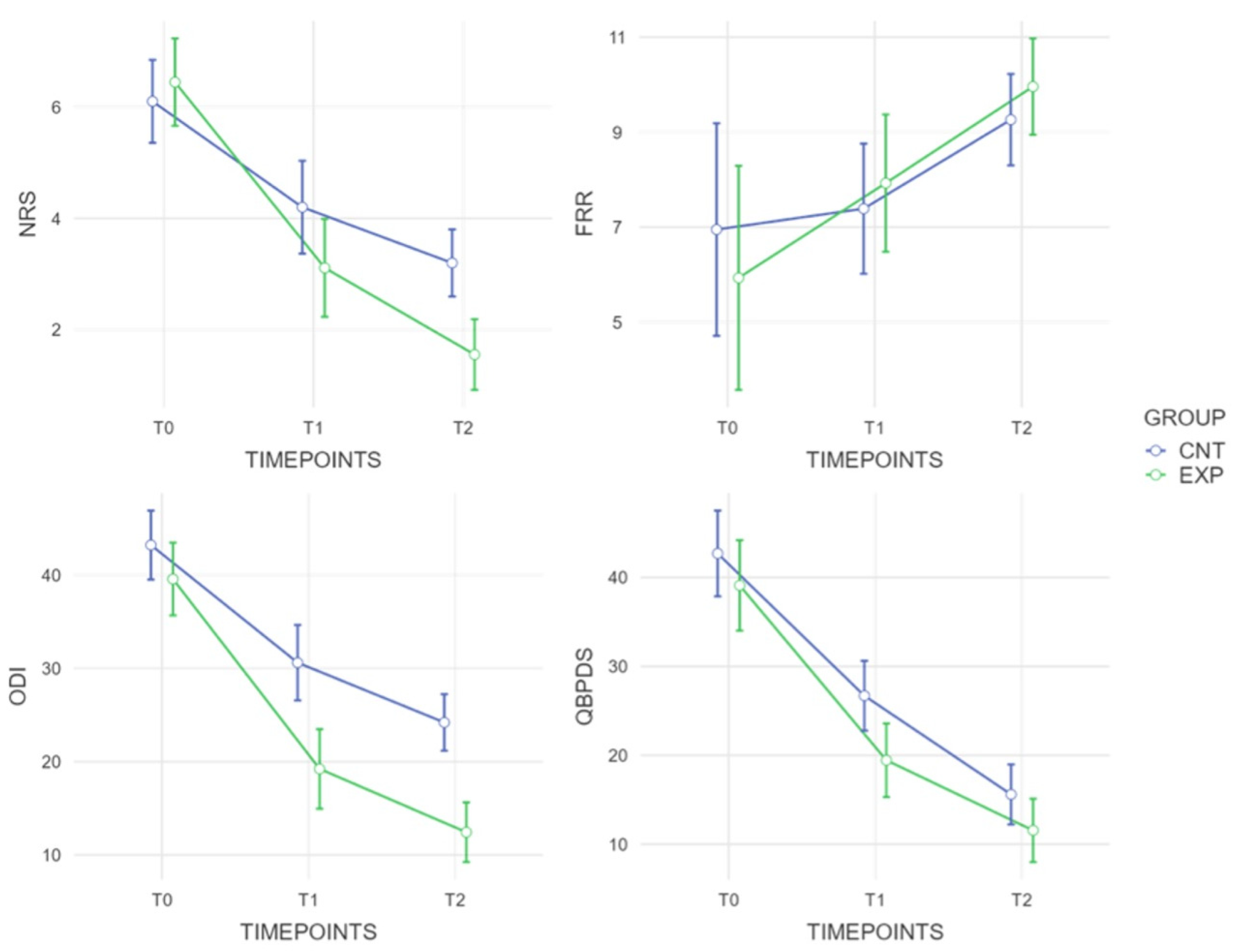

| Outcome | Group | T0 | T1 | T2 | Group × Time Interaction p-Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FRR | EXP | 5.93 | ± | 3.174 | 7.93 | ± | 2.246 | 9.96 | ± | 1.316 | |

| CNT | 6.95 | ± | 3.506 | 7.39 | ± | 1.865 | 9.26 | ± | 1.545 | 0.942 (η2gen = 0.039) | |

| between group | p = 0.51, MD = 1.018, ES: 0.303 | p = 0.57, MD = −0.53, ES: −0.261 | p = 0.31, MD = −0.69, ES: −0.480 | ||||||||

| ODI | EXP | 39.56 | ± | 7.178 | 19.22 | ± | 6.22 | 12.44 | ± | 2.555 | |

| CNT | 43.2 | ± | 3.458 | 30.6 | ± | 5.892 | 24.2 | ± | 5.75 | <0.001 (η2gen =0.107) | |

| between group | p = 0.17, MD = 3.644, ES: 0.659 | p < 0.001, MD = 11.37, ES: 0.883 | p < 0.001, MD = 11.75, ES: 0.591 | ||||||||

| QBPDS | EXP | 39.11 | ± | 6.864 | 19.44 | ± | 2.186 | 11.56 | ± | 5.79 | |

| CNT | 42.7 | ± | 7.543 | 26.7 | ± | 7.818 | 15.6 | ± | 4.3 | 0.035 (η2gen = 0.049) | |

| between group | p = 0.29, MD = 3.589, ES: 0.496 | p = 0.02, MD = 7.25, ES: 0.731 | p = 0.1, MD = 4.04, ES: 0.820 | ||||||||

| NRS | EXP | 6.44 | ± | 0.882 | 3.11 | ± | 1.054 | 1.65 | ± | 1.03 | |

| CNT | 6.1 | ± | 1.287 | 4.2 | ± | 1.398 | 2.9 | ± | 0.738 | 0.046 (η2gen = 0.128) | |

| between group | p = 0.51, MD = −0.344, ES: −0.309 | p = 0.07, MD = 1.08, ES: 0.575 | p = 0.03, MD = 1.16, ES: 0.411 | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marotta, N.; de Sire, A.; Pisani, F.; Mercurio, M.; Lopresti, E.; Scozzafava, L.; Parente, A.; Gasparini, G.; Longo, U.G.; Ammendolia, A. Effects of Pilates Matwork Core Exercises on Functioning in Middle-Aged Adult Women with Chronic Nonspecific Low Back Pain Through Flexion Relaxation Phenomenon Analysis: A Pilot RCT. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 433. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040433

Marotta N, de Sire A, Pisani F, Mercurio M, Lopresti E, Scozzafava L, Parente A, Gasparini G, Longo UG, Ammendolia A. Effects of Pilates Matwork Core Exercises on Functioning in Middle-Aged Adult Women with Chronic Nonspecific Low Back Pain Through Flexion Relaxation Phenomenon Analysis: A Pilot RCT. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2025; 10(4):433. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040433

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarotta, Nicola, Alessandro de Sire, Federica Pisani, Michele Mercurio, Ennio Lopresti, Lorenzo Scozzafava, Andrea Parente, Giorgio Gasparini, Umile Giuseppe Longo, and Antonio Ammendolia. 2025. "Effects of Pilates Matwork Core Exercises on Functioning in Middle-Aged Adult Women with Chronic Nonspecific Low Back Pain Through Flexion Relaxation Phenomenon Analysis: A Pilot RCT" Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 10, no. 4: 433. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040433

APA StyleMarotta, N., de Sire, A., Pisani, F., Mercurio, M., Lopresti, E., Scozzafava, L., Parente, A., Gasparini, G., Longo, U. G., & Ammendolia, A. (2025). Effects of Pilates Matwork Core Exercises on Functioning in Middle-Aged Adult Women with Chronic Nonspecific Low Back Pain Through Flexion Relaxation Phenomenon Analysis: A Pilot RCT. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 10(4), 433. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040433