Therapeutic Physical Exercise for Dysmenorrhea: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What therapeutic physical exercise programs were used to reduce pain in women with dysmenorrhea?

- What exercise protocols were used to reduce pain in women with dysmenorrhea?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

- Population: women with dysmenorrhea

- Concept: therapeutic physical exercise program and exercise protocols considered to manage dysmenorrhea

- Context: open context-practice of physical exercise and exercise protocols in outpatient physiotherapy clinics and cabinets, in rehabilitation centers, and home-based settings

2.2. Evidence Sources

2.3. Research Strategy

2.4. Evidence Selection

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Analysis and Results Presentation

3. Results

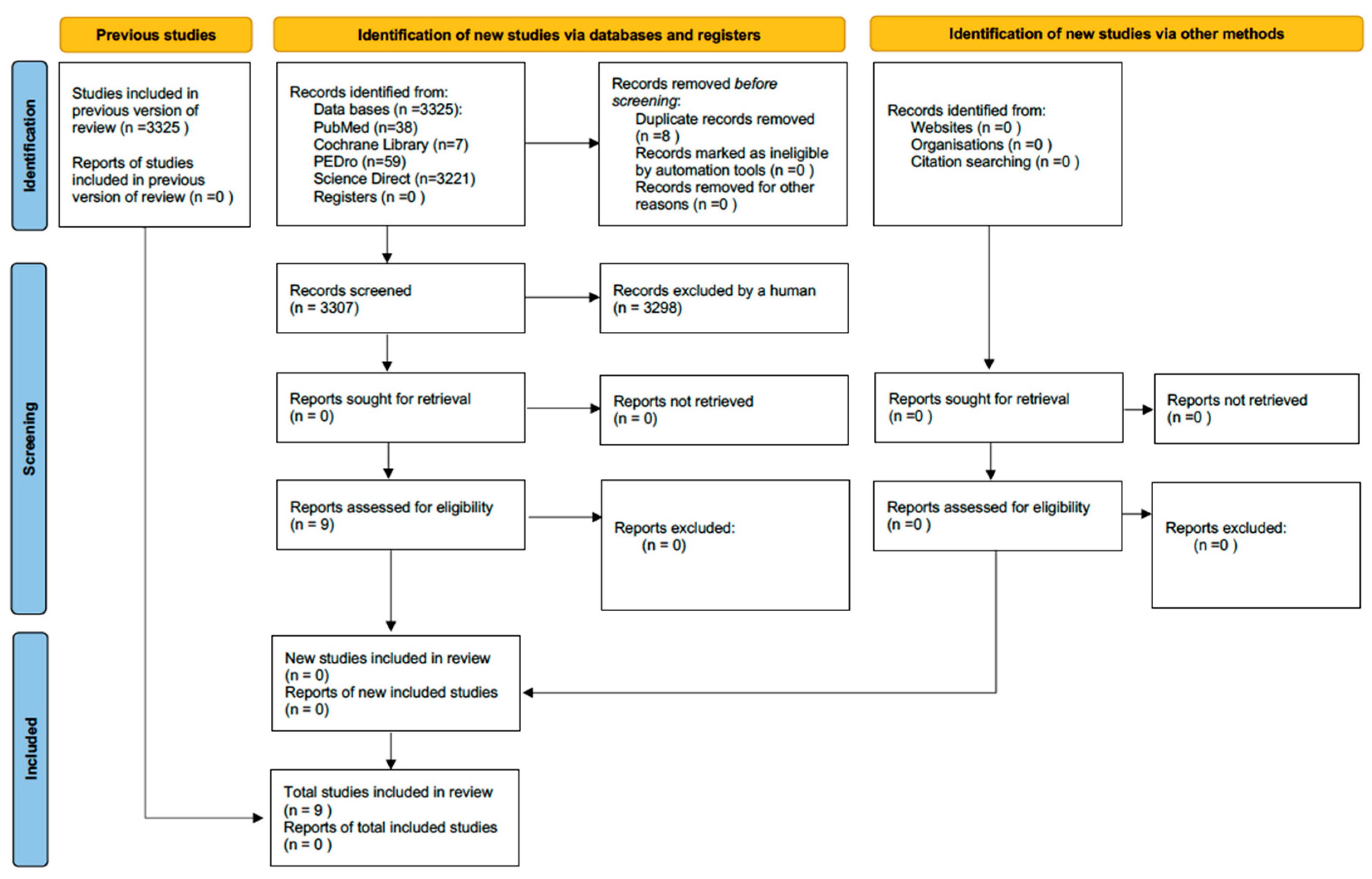

3.1. Selection of Evidence Sources

3.2. Types of Study

3.3. Objectives

3.4. Participants

3.5. Intervention Program

3.6. Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bernardi, M.; Lazzeri, L.; Perelli, F.; Reis, F.M.; Petraglia, F. Dysmenorrhea and related disorders. F1000Res 2017, 6, 1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, C.L.; Farquhar, C.; Roberts, H.; Proctor, M. Oral contraceptive pill for primary dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009, 4, CD002120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armour, M.; Smith, C.A.; Steel, K.A.; Macmillan, F. The effectiveness of self-care and lifestyle interventions in primary dysmenorrhea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 19, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guimarães, I.; Póvoa, A.M. Primary Dysmenorrhea: Assessment and Treatment. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obstet. 2020, 42, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koninckx, P.R.; Fernandes, R.; Ussia, A.; Schindler, L.; Wattiez, A.; Al-Suwaidi, S.; Amro, B.; Al-Maamari, B.; Hakim, Z.; Tahlak, M. Pathogenesis Based Diagnosis and Treatment of Endometriosis. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 745548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osayande, A.S.; Mehulic, S. Diagnosis and initial management of dysmenorrhea. Am. Fam. Physician 2014, 89, 341–346. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, F.C.; Driver, H.S.; Rogers, G.G.; Paiker, J.; Mitchell, D. High nocturnal body temperatures and disturbed sleep in women with primary dysmenorrhea. Am. J. Physiol. 1999, 277, 1013–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacovides, S.; Avidon, I.; Baker, F.C. What we know about primary dysmenorrhea today: A critical review. Hum. Reprod. Update 2015, 21, 762–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenna, K.A.; Fogleman, C.D. Dysmenorrhea. Am. Fam. Physician 2021, 104, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- MacKichan, F.; Paterson, C.; Henley, W.E.; Britten, N. Self-care in people with long term health problems: A community based survey. BMC Fam. Pract. 2011, 12, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armour, M.; Dahlen, H.G.; Smith, C.A. More Than Needles: The Importance of Explanations and Self-Care Advice in Treating Primary Dysmenorrhea with Acupuncture. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat Med. 2016, 2016, 3467067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- French, L. Dysmenorrhea. Am. Fam. Physician 2005, 71, 285–291. [Google Scholar]

- Ziaei, S.; Zakeri, M.; Kazemnejad, A. A randomised controlled trial of vitamin E in the treatment of primary dysmenorrhoea. BJOG 2005, 112, 466–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amorosi, M. Correlation between sport and depression. Psychiatr. Danub. 2014, 26, 208–210. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, E.; Shivakumar, G. Effects of exercise and physical activity on anxiety. Front. Psychiatry 2013, 4, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harber, V.J.; Sutton, J.R. Endorphins and exercise. Sports Med. 1984, 1, 154–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bielecki, J.E.; Tadi, P. Therapeutic Exercise; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Caspersen, C.J.; Powell, K.E.; Christenson, G.M. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: Definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public. Health Rep. 1985, 100, 126–131. [Google Scholar]

- Berghmans, B. Physiotherapy for pelvic pain and female sexual dysfunction: An untapped resource. Int. Urogynecol J. 2018, 29, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azima, S.; Bakhshayesh, H.R.; Abbasnia, K.; Kaviani, M.; Sayadi, M. Effect of Isometric Exercises on PrimaryDysmenorrhea: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. GMJ 2015, 4, 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Heidarimoghadam, R.; Abdolmaleki, E.; Kazemi, F.; Masoumi, S.Z.; Khodakarami, B.; Mohammadi, Y. The Effect of Exercise Plan Based on FITT Protocol on Primary Dysmenorrhea in Medical Students: A Clinical Trial Study. J. Res. Health Sci. 2019, 19, e00456. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kannan, P.; Chapple, C.M.; Miller, D.; Claydon-Mueller, L.; Baxter, G.D. Effectiveness of a treadmill-based aerobic exercise intervention on pain, daily functioning, and quality of life in women with primary dysmenorrhea: A randomized controlled trial. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2019, 81, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, K.; Sudhakar, S.; Aravind, S.; Kumar, C.P.; Monika, S. Efficacy of Yoga Asana and Gym Ball Exercises in the management of primary dysmenorrhea: A single-blind, two group, pretest-posttest, randomized controlled trial. CHRISMED J. Health Res. 2018, 5, 118–122. [Google Scholar]

- Dehnavi, Z.M.; Jafarnejad, F.; Kamali, Z. The Effect of aerobic exercise on primary dysmenorrhea: A clinical trial study. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2018, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnett, M.; Lemyre, M. No. 345-Primary Dysmenorrhea Consensus Guideline. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2017, 39, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armour, M.; Sinclair, J.; Chalmers, K.J.; Smith, C.A. Self-management strategies amongst Australian women with endometriosis: A national online survey. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 19, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbaş, E.; Erdem, E.U. Effectiveness of Group Aerobic Training on Menstrual Cycle Symptoms in Primary Dysmenorrhea. Med. J. Bakirkoy 2019, 15, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhiya, M.; Senthil Selvam, P.; Manoj Abraham, M.; Palekar, T.J.; Sundaram, M.S.; Priya, K.; Christina, J. A Study To Compare The Effects Of Aerobic Exercise Versus Core Strengthening Exercise Among College Girls With Primary Dysmenorrhea. Int. J. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 11, 2692–2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudelist, G.; Fritzer, N.; Thomas, A.; Niehues, C.; Oppelt, P.; Haas, D.; Tammaa, A.; Salzer, H. Diagnostic delay for endometriosis in Austria and Germany: Causes and possible consequences. Hum. Reprod. 2012, 12, 3412–3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staal, A.H.; van der Zanden, M.; Nap, A.W. Diagnostic Delay of Endometriosis in the Netherlands. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 2016, 81, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parazzini, F.; Di Martino, M.; Pellegrino, P. Magnesium in the gynecological practice: A literature review. Magnes. Res. 2017, 30, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorena, S.B.; Lima, M.C.; Ranzolin, A.; Duarte, Â.L. Effects of muscle stretching exercises in the treatment of fibromyalgia: A systematic review. Rev. Bras. Reumatol. 2015, 55, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeed, S.A.; Cunningham, K.; Bloch, R.M. Depression and Anxiety Disorders: Benefits of Exercise, Yoga, and Meditation. Am. Fam. Physician 2019, 99, 620–627. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saud, A.; Abbasi, M.; Merris, H.; Parth, P.; Jones, X.M.; Aggarwal, R.; Gupta, L. Harnessing the benefits of yoga for myositis, muscle dystrophies, and other musculoskeletal disorders. Clin. Rheumatol. 2022, 41, 3285–3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, B.C.; Pak, A.W. Multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity, and transdisciplinarity in health research, services, education and policy: 2. Promotors, barriers, and strategies of enhancement. Clin. Investig. Med. 2007, 30, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Körner, M. Interprofessional teamwork in medical rehabilitation: A comparison of multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary team approach. Clin. Rehabil. 2010, 24, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vercellini, P.; Buggio, L.; Frattaruolo, M.P.; Borghi, A.; Dridi, D.; Somigliana, E. Medical treatment of endometriosis-related pain. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 51, 68–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cagnacci, A. Hormonal contraception: Venous and arterial disease. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2017, 22, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skovlund, C.W.; Mørch, L.S.; Kessing, L.V.; Lidegaard, Ø. Association of Hormonal Contraception With Depression. JAMA Psychiatry 2016, 73, 1154–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuercher, B. Impact des médicaments sur l’environnement. Rev. Med. Suisse 2022, 18, 1471–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Database | Research Expression | Added Filters |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | (dysmenorrhea OR period pain OR uterine pain) AND (physical exercises OR physical activities OR physical exercise program) AND (analgesia OR pain relief) | - Text availability: Free full text - Article type: Clinical trial; RCT - Publication date: custom range “start date = 1 January 2013”; “end date = 30 April 2023” |

| ScienceDirect | (dysmenorrhea OR period pain OR uterine pain) AND (physical exercises OR physical activities OR physical exercise program) AND (analgesia OR pain relief) | - Years: 2013 to 2023, included - Article type: research article; case reports; data articles; discussion; editorials; practice guidelines; short communications; others - Access type: “Open access & Opened archive” |

| PEDro | - Problem: pain - Body part: perineum or genito-urinary system - Therapy: fitness training; strength training - When searching: Match all search terms (AND) | - Methods: practice guideline; clinical trial - Published since: 2013 |

| Cochrane Library | (dysmenorrhea OR period pain OR uterine pain) AND (physical exercises OR physical activities OR physical exercise program) AND (analgesia OR pain relief) | - Date: custom range = 1 January 2013 to 30 April 2023 |

| Authors /Year | Study | Objectives | Participants Characteristics | Intervention Program | Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akbaş & Erdem, 2019 [29] | Experimental study | Investigating the effectiveness of an aerobic training program on premenstrual symptoms, menstrual symptoms, emotional state and quality of life in women with primary dysmenorrhea | Sample: - N = 37 women: - NEG = 18 women - NCG = 19 women Age: EG: 21.10 ± 1.59 years CG: 21.20 ± 1.47 years | Program: - GE: aerobic training program - GC: no intervention Aerobic training: - For 4 weeks, 3 times a week, each time for 50 min - Pain intensity assessed using VAS - Emotional state assessed with the BAI - Quality of life assessed using the SF-36 form Context: under the supervision of an experienced physiotherapist | Premenstrual and menstrual symptoms, emotional state and quality of life | |

| Armour, Sinclair, et al., 2019 [28] | Cross-sectional study | To determine the prevalence of use, safety and self-rated efficacy of common forms of self-management in women with endometriosis | Sample: - N = 484 responses Age: 18–45 years | Program: Cannabis—heat—dietary options (such as gluten-free, vegan)—hemp oil/CBD oil—acupressure—cold—massage—rest—exercise—medicinal herbs—stretching—meditation/breathing—yoga/Pilates—Tai-chi/Qigong Questionnaire: Questionnaire: define physical and/or psychological techniques that women could carry out on their own or lifestyle interventions Context: online questionnaire | Pain | |

| Azima et al., 2015 [22] | RCT | Investigating the effect of isometric exercises on the intensity and duration of pain and anxiety levels in students with primary dysmenorrhea | Sample: - N = 68 students - NEG = 34 students - NCG = 34 students Age: EG: 21.08 ± 1.21 years CG: 20.73 ± 1.08 years | Program: - EG: isometric exercises - CG: no intervention Isometric exercises: - From the 3rd day of the menstrual cycle - For 8 weeks - Pain intensity assessed using VAS - Anxiety assessed using a questionnaire Context: autonomous exercises by students from Shiraz University; support from a conductor specializing in rehabilitation | Pain and anxiety | |

| Burnett & Lemyre, 2017 [27] | Guideline review | Investigations and treatment of primary dysmenorrhea | N/A | Program: Medical treatment: non-hormonal therapy (acetaminophen; non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs)—hormonal treatment (combined hormonal contraceptives; progesterone regimens) Complementary and alternative therapy: exercise—TENS—acupuncture/acupressure—behavioral intervention—topical heat—food choices Surgical management: laparoscopy—treatment for endometriosis—conservative surgical procedures—surgical options in the absence of visual abnormalities Context: N/A | N/A | |

| Dehnavi et al., 2018 [26] | Clinical trials | Investigating the effect of regular aerobic exercise on the severity of primary dysmenorrhea | Sample: - N = 70 women - NEG = 35 women - NCG = 35 women Age: EG: 41.4 ± 22.25 years CG: 71.4 ± 6.24 years | Program: - EG: aerobic exercise - CG: no intervention Aerobic exercise: - For 8 weeks, 3 times a week, for 30 min - Visual pain questionnaire completed by the 2 groups in the first 3 days of the menstrual cycle Context: wherever the participant wants to train, from CD and educational posters containing all the movements performed, handed out at the end of the learning session | Menstrual symptoms: mainly pain, but also nausea and vomiting, bruising and headache, and a general malaise | |

| Heidarimoghadam et al., 2019 [23] | RCT | To investigate the effects of exercise based on a specific protocol on the severity and duration of primary dysmenorrhea | Sample: - N = 86 students - NEG = 43 students - NCG = 43 students Age: 18–24 years | Program: - EG: FITT protocol-based exercise - CG: physical education class Exercise based on FITT protocol: - For 8 weeks, each with 3 sessions (24 sessions) - Sports protocol proposed by the ACSM with four pillars: frequency of sports sessions, exercise intensity, exercise time and type of exercise. Physical education class: - Once a week, they also do group exercises (volleyball, badminton) for 1 h 30 Context: in gyms using a program that was taught by a sports instructor and a trained researcher | Pain | |

| Kannan et al., 2019 [24] | RCT | To evaluate the effectiveness of an aerobic treadmill exercise intervention on the pain and symptoms associated with primary dysmenorrhea | Sample: - N = 70 women - NGE = 35 women - NGC = 35 women Age: 18–43 years | Program: - EG: regular aerobic exercise - CG: usual care Aerobic training: - On the treadmill - For 4 weeks, 3 times a week - 70 to 85% of maximum heart rate - Preceded by 10-min warm-up exercises - Followed by relaxation exercises for 10 min, including stretches for the lower back, stretches for the pelvic region and strengthening of the abdominal and gluteal muscles - Exercise between periods, no exercise during the week of menstruation Context: at the Otago University School of Physiotherapy with a registered physiotherapist with 3 years’ experience specializing in pain and women’s health, and at home | Pain and quality of life | |

| Sandhiya M et al., 2020 [30] | Quasi-experimental study | To evaluate and compare the effect of aerobic exercise and core strengthening in primary dysmenorrhea | Sample: - N = 30 students - NGA = 15 students - NGB = 15 students Age: 18–25 years | Program: - GA: aerobic exercise - GB: core strengthening exercise with a small stability ball Aerobic exercise: - For 8 weeks, 3 times a week, each time for 40 min - Measuring instruments: VMSS and MMDQ Context: at home | Pain and quality of life | |

| Padmanabhan, K, et al., 2018 [25] | RCT | Comparing the effectiveness of yoga asana and gym ball/therapy ball/swiss ball exercises in treating women with primary dysmenorrhea | Sample: - N = 30 women - NGA = 15 women - NGB = 15 women Age: GA: 20.2 ± 3.8 years GB: 20.7 ± 3.1 years | Program: - GA: yoga asana classes - GB: exercises with a gym ball/therapy ball/swiss ball Context: supervised during the first session by qualified people with more than 5 years’ experience in yoga; unsupervised, in autonomy (at home), during the other sessions | Pain associated with primary dysmenorrhea | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rigal, P.; Bonnet, S.; Vieira, Á.; Carvalhais, A.; Lopes, S. Therapeutic Physical Exercise for Dysmenorrhea: A Scoping Review. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10010010

Rigal P, Bonnet S, Vieira Á, Carvalhais A, Lopes S. Therapeutic Physical Exercise for Dysmenorrhea: A Scoping Review. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2025; 10(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleRigal, Philippine, Salomé Bonnet, Ágata Vieira, Alice Carvalhais, and Sofia Lopes. 2025. "Therapeutic Physical Exercise for Dysmenorrhea: A Scoping Review" Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 10, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10010010

APA StyleRigal, P., Bonnet, S., Vieira, Á., Carvalhais, A., & Lopes, S. (2025). Therapeutic Physical Exercise for Dysmenorrhea: A Scoping Review. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 10(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10010010