Sex and Relationship Education for Individuals with Disabilities: A Review of the Literature Through an Ecological Systems Lens

Abstract

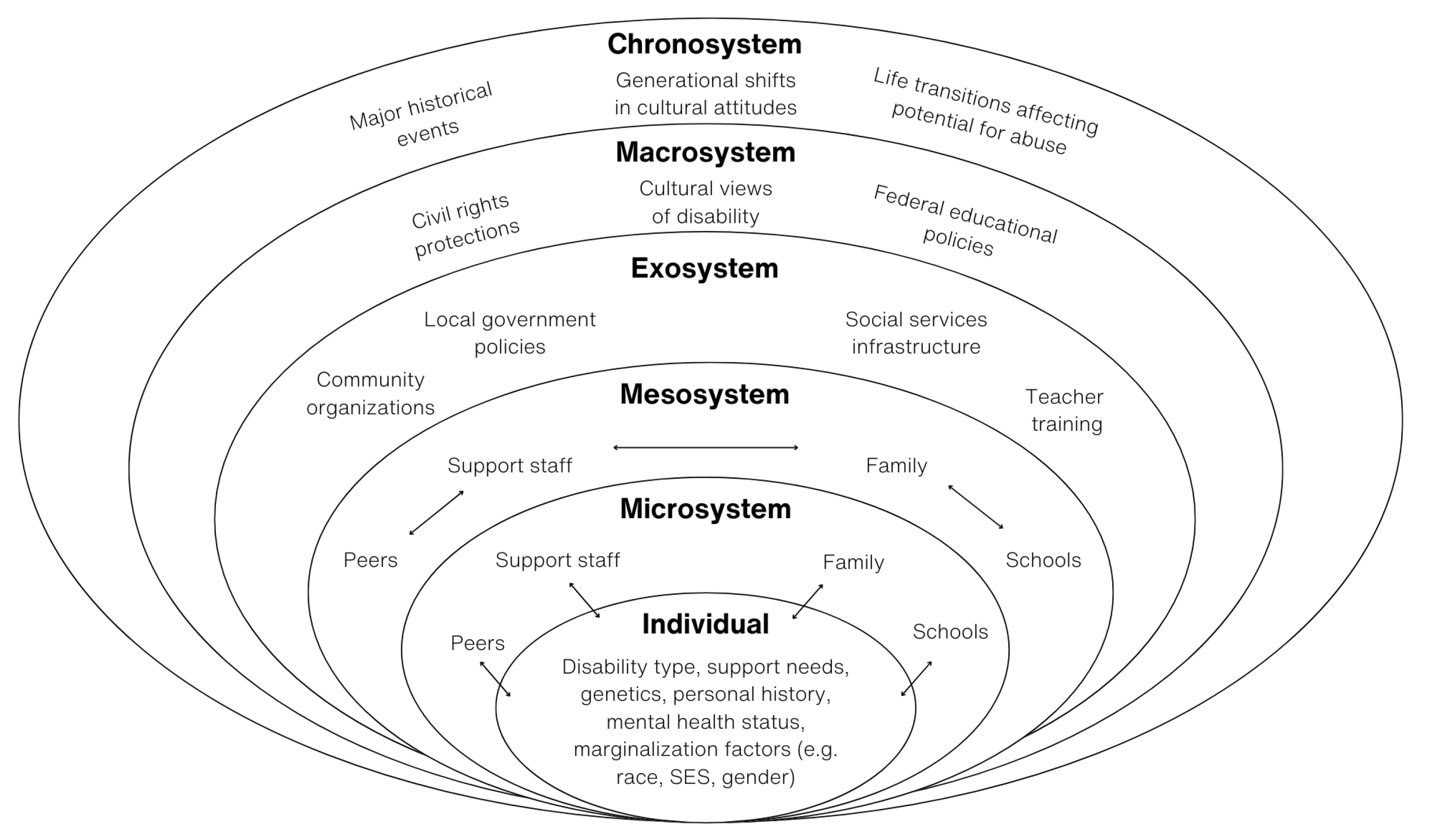

1. Introduction

The Present Paper

2. Theoretical Frameworks

2.1. Chronosystem and Macrosystem Influences: Historical Events, Cultural Attitudes, Policy

2.2. Exosystem and Mesosystem Influences: Responsibility for Teaching Relationships and Sexuality

2.3. Microsystem Influences: Perceptions of Caregivers and Educators

2.4. The Role of the Individual: Experience, Preference, and Voice

3. Summary and Key Points

| Challenge Outlined in the Literature | Supporting Evidence | Emerging Literature, Practical Solutions, and Future Directions | Supporting Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. There are misconceptions about disabilities, disabled individuals’ needs and desires, and the relevance of SREs for individuals with disabilities. | Educators and caregivers often carry implicit biases that skew their perceptions of disabled individuals. Sociocultural values and sociopolitical contexts influence whether SRE is offered and how and what is taught. Societal beliefs that people with disabilities ‘lack sexual desire’ or are ‘incapable of understanding or taking part in sexual relationships’ influence access to SRE. There are minimal or no requirements for people with disabilities to receive SRE within or outside school settings. | There is a need to: Address stigma around disability. Recognize and remove implicit biases about sexuality in people with disabilities. Understand disability through an asset-based lens, viewing people with disabilities as capable and sexual beings with rights, interests, and autonomy. View sexuality as important for a positive self-view. | *[9] [37] *[2] *[1] [7] *[25] [29] *[43] [42] |

| 2. Caregivers often feel uncomfortable initiating and facilitating conversations centered on sexuality and relationships. | Caregivers have turned to healthcare professionals for guidance. Caregivers have indicated that SRE may not be appropriate or useful for their children. Caregivers often do not give permission for their child to participate in SRE programs. Caregivers often shelter their disabled children from education in an effort to keep them safe. Studies have found that shared responsibility of SRE content delivery between caregivers and educators reduces caregiver discomfort. | Researchers have begun developing programs to help empower families with SRE delivery. There is a need to: Acknowledge and address attitudes and feelings of uncertainty or discomfort. Facilitate conversations with caregivers centered on problems with sheltering people with disabilities. Develop comprehensive and ongoing collaborative training with and for caregivers, educators, and service providers that includes depth and breadth of relationship and sexuality topics. | *[33] *[36] [37] [35] *[1] *[38] *[31] *[34] |

| 3. There is limited training for educators in addressing sexuality and dating with disabled individuals. | There is ambiguity about who feels responsible for delivering sexual education. Educators often feel they do not have the expertise to teach SRE or provide mentorship to their disabled students. Teacher preparation does not exist, or it is limited or inadequate. There is often limited curricular time and resources for SRE. Educators have felt some resistance from caregivers. | There is a need to: Include relationship development and sexuality topics within educational curriculum; embed SRE instructional time and resources into the school day. Better prepare general and special educators as well as school specialists in SRE instruction. Improve communication between educational teams, outlining student goals and aims centered around sexuality and relationship development. Improve communication between caregivers and educators about the importance of SRE. | [28] [30] [29] *[31] [35] *[36] [7] |

| 4. SRE curricula content often does not align with individuals’ interests, desires, and lived experiences. | There is often an over-emphasis on the biological aspects of human sexuality within SRE programs and an under-emphasis on social aspects of human relationships and sexuality. Individuals with disabilities have unique perspectives, needs, and experiences that significantly influence their understanding and approach to relationships and sexual health. There is a mismatch between what an individual wants and what others want for them. | Studies are starting to include people with disabilities in the design and development of SRE and develop tailored SRE curricula. There is a need to: Listen to and learn from the perspectives and experiences of people with disabilities. Co-develop SRE content to align with the needs, desires, interests, perspectives, and experiences of the disability community. | *[6] *[24] *[1] [7] *[2] [8] [40] |

| 5. Rigid or highly structured SRE may overlook individual differences and focus on extinguishing problematic behavior rather than supporting human development. | People with disabilities show varying levels of SRE knowledge and skills, have different experiences, and need different degrees of support. Implementing rigid, rule-based instruction without a more holistic approach leaves people with disabilities feeling unsure of how to navigate relationships and sexuality. Educators have viewed developmentally appropriate sexual behavior as disruptive or problematic rather than as part of the human condition. | There is a need to: Develop person-centered programs that are adaptable to individual needs and strengths and responsive to cultural contexts and lived experiences. Ensure that people with disabilities have agency and control over their personal goals. Focus on application and generalization of learned skills. | *[31] *[2] [37] *[1] [42] *[45] |

| 6. High-quality SRE is often inaccessible to people with disabilities. | Studies have documented that people with disabilities feel safe discussing SRE topics with their peers and learn from their peers’ experiences with relationships and dating, yet people with disabilities often have limited access to connect with peers and participate in socially rich learning opportunities. People with disabilities often seek information about sex and relationships from unreliable, unregulated, and often, inaccurate media sources and online forums. Studies have documented vast variability in the content, delivery, and quality of SRE offered to the disability community. | There is a need to: Promote opportunities for people with disabilities to discuss content with peers, social skills training and relationship modeling and coaching, and peer-to-peer education opportunities. Promote inclusion, understanding, and accessibility of content through a range of teaching methods and tools, such as using technology, video modeling, social narratives and scripts, and pictures. Provide clear, practical, relatable guidance and feedback and information about on-line safety. | *[26] [40] *[38] *[5] *[4] *[6] *[1] [37] |

Limitations and Areas for Future Research and Directions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Coulter, D.; Lynch, C.; Joosten, A.V. Exploring the perspectives of young adults with developmental disabilities about sexuality and sexual health education. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2023, 70, 380–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, S.F.E.I. Sexual education for adolescents and adults with intellectual disabilities: Systematic review. Sex. Disabil. 2024, 42, 119–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, L.; Sexuality Information; Education Council of the United States [SIECUS]. Comprehensive Sex Education for Youth with Disabilities: A Call to Action. UNESCO.org. 2021. Available online: https://healtheducationresources.unesco.org/library/documents/comprehensive-sex-education-youth-disabilities-call-action (accessed on 6 August 2024).

- Brown-Lavoie, S.M.; Viecili, M.A.; Weiss, J.A. Sexual knowledge and victimization in adults with autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2014, 44, 2185–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaafsma, D.; Kok, G.; Stoffelen, J.M.T.; Curfs, L.M.G. Identifying effective methods for teaching sex education to individuals with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review. J. Sex Res. 2014, 52, 412–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, G.; Hooley, M.; Attwood, T.; Mesibov, G.; Stokes, M. Autism and intellectual disability: A systematic review of sexuality and relationship education. Sex. Disabil. 2019, 37, 353–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graff, H.J.; Moyher, R.E.; Bair, J.; Foster, C.; Gorden, M.E.; Clem, J. Relationships and sexuality: How is a young adult with an intellectual disability supposed to navigate? Sex. Disabil. 2017, 36, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedgrift, K.; Sparapani, N. The development of a social-sexual education program for adults with neurodevelopmental disabilities: Starting the discussion. Sex. Disabil. 2022, 40, 503–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wit, W.; van Oorsouw, W.M.W.J.; Embregts, P.J.C.M. Sexuality, education and support for people with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review of the attitudes of support staff and relatives. Sex. Disabil. 2022, 40, 315–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAndrews, P. “Nothing About Us Without Us”: Disability Justice and Inclusive Sex Education for Students with Disabilities. SIECUS: Sex Ed for Social Change. 3 December 2024. Available online: https://siecus.org/disability-justice-and-inclusive-sex-education-for-students-with-disabilities/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Shapiro, J. The Sexual Assault Epidemic No One Talks About. NPR. 8 January 2019. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2018/01/08/570224090/the-sexual-assault-epidemic-no-one-talks-about (accessed on 6 August 2024).

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (Ed.) Making Human Beings Human: Bioecological Perspectives on Human Development; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff, A.J. (Ed.) The Transactional Model of Development: How Children and Contexts Shape Each Other; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa, H.; Hsueh, J. Child development and public policy: Toward a dynamic systems perspective. Child Dev. 2001, 72, 1887–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Public Radio [NPR]. The Supreme Court Ruling Led to 70,000 Forced Sterilizations, N.P.R. 7 March 2016. Available online: https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2016/03/07/469478098/the-supreme-court-ruling-that-led-to-70-000-forced-sterilizations (accessed on 6 August 2024).

- Kempton, W.; Kahn, E. Sexuality and people with intellectual disabilities: A historical perspective. Sex. Disabil. 1991, 9, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Women’s Law Center. New NWLC Report Finds over 30 States Legally Allow Forced Sterilization; National Women’s Law Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2 February 2022; Available online: https://nwlc.org/press-release/new-nwlc-report-finds-over-30-states-legally-allow-forced-sterilization/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights; United Nations. 2006. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-persons-disabilities (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Status of Ratification Interactive Dashboard. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights; United Nations. 2014. Available online: https://indicators.ohchr.org/ (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Hall, K.S.; McDermott Sales, J.; Komro, K.A.; Santelli, J. The state of sex education in the United States. J. Adolesc. Health Off. Publ. Soc. Adolesc. Med. 2016, 58, 595–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guttmacher Institute. Sex and HIV Education. Guttmacher Institute. 2023. Available online: https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/sex-and-hiv-education (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Ogur, C.; Olcay, S.; Baloglu, M. An international study: Teachers’ opinions about individuals with developmental disabilities regarding sexuality education. Sex. Disabil. 2023, 41, 739–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, A.; Dillenburger, K. Sexual health education for children and young people with autism and/or intellectual/development disabilities in the Arab world: A systematic literature review of the attitudes and experiences of parents and professionals. Sex. Disabil. 2025, 43, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normand, C.L.; Sallafranque-St-Louis, F. Cybervictimization of young people with an intellectual or developmental disability: Risks specific to sexual solicitation. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2016, 29, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, E.; Vasudevan, V. Issues of violence affecting people with disabilities. In Proceedings of the APHA’s 2020 VIRTUAL Annual Meeting and Expo, Online, 24–28 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, K.E. Sexuality Education for Students with IDD: Factors Impacting Special Education Teacher Confidence. Doctoral dissertation, Fordham University, Bronx, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hole, R.; Schnellert, L.; Cantle, G. Sex: What is the big deal? Exploring individuals’ with intellectual disabilities experiences with sex education. Qual. Health Res. 2022, 32, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krantz, G.; Tolan, V.; Pontarelli, K.; Cahill, S.M. What do adolescents with developmental disabilities learn about sexuality and dating? A potential role for occupational therapy. Open J. Occup. Ther. 2016, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, K.; Quain, J.; Castell, E. Stop leaving people with disability behind: Reviewing comprehensive sexuality education for people with disability. Health Educ. J. 2024, 83, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eglseder, K.; Webb, S.; Rennie, M. Sexual functioning in occupational therapy education: A survey of programs. Open J. Occup. Ther. 2018, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torralbas-Ortega, J.; Valls-Ibáñez, V.; Roca, J.; Sastre-Rus, M.; Campoy-Guerrero, C.; Sala-Corbinos, D.; Sánchez-Fernández, M. Affectivity and Sexuality in Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder from the Perspective of Education and Healthcare Professionals: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borawska-Charko, M.; Mick, W.; Stagg, S.D. “More than just the curriculum to deal with”: Experiences of teachers delivering sex and relationship education to people with intellectual disabilities. Sex. Disabil. 2023, 41, 201–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, K.; Sandman, L. Supporting parents as sexuality educators for individuals with intellectual disability: The development of the Home B.A.S.E curriculum. Sex. Disabil. 2019, 37, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornman, J.; Rathbone, L. A sexuality and relationship training program for women with intellectual disabilities: A social story approach. Sex. Disabil. 2016, 34, 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Schmidt, E.K.; Hand, B.N.; Havercamp, S.; Sommerich, C.; Weaver, L.; Darragh, A. Sex education practices for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A qualitative study. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2021, 75, 7503180060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frawley, P.; Wilson, N.J. Young people with intellectual disability talking about sexuality education and information. Sex. Disabil. 2016, 34, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houck, E.J.; Dracobly, J.D. Trauma-informed care for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities: From disparity to policies for effective action. Perspect. Behav. Sci. 2022, 46, 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, A.J.; Kelley, K.R.; Raxter, A. Effects of PEERS® social skills training on young adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities during college. Behav. Modif. 2021, 45, 297–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheak-Zamora, N.C.; Teti, M.; Maurer-Batjer, A.; O’Connor, K.V.; Randolph, J.K. Sexual and relationship interest, knowledge, and experiences among adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2019, 48, 2605–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, B.H.; Vidal, P.; Chiao, R.; Pantalone, D.W.; Faja, S. Sexual knowledge, experiences, and pragmatic language in adults with and without autism: Implications for sex education. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2023, 53, 3770–3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michielsen, K.; Brockschmidt, L. Barriers to sexuality education for children & young people with disabilities in the WHO European region: A scoping review. Sex Educ. 2021, 21, 674–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, R.B.; Robinson-Whelen, S.; Davis, L.A.; Meadours, J.; Kincaid, O.; Howard, L.; Millin, M.; Schwartz, M.; McDonald, K.E.; Safety Project Consortium. Evaluation of a safety awareness group program for adults with intellectual disability. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2020, 125, 304–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkogkos, G.; Staveri, M.; Galanis, P.; Gena, A. Sexual education: A case study of an adolescent with a diagnosis of pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified and intellectual disability. Sex. Disabil. 2021, 39, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oppermann, G.; Van Zant, C.; Coughlan, I.; Howarth, S.; Sparapani, N.; Pedgrift, K. Sex and Relationship Education for Individuals with Disabilities: A Review of the Literature Through an Ecological Systems Lens. Sexes 2025, 6, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6030052

Oppermann G, Van Zant C, Coughlan I, Howarth S, Sparapani N, Pedgrift K. Sex and Relationship Education for Individuals with Disabilities: A Review of the Literature Through an Ecological Systems Lens. Sexes. 2025; 6(3):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6030052

Chicago/Turabian StyleOppermann, Gustav, Caroline Van Zant, Isabel Coughlan, Sophie Howarth, Nicole Sparapani, and Kathryn Pedgrift. 2025. "Sex and Relationship Education for Individuals with Disabilities: A Review of the Literature Through an Ecological Systems Lens" Sexes 6, no. 3: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6030052

APA StyleOppermann, G., Van Zant, C., Coughlan, I., Howarth, S., Sparapani, N., & Pedgrift, K. (2025). Sex and Relationship Education for Individuals with Disabilities: A Review of the Literature Through an Ecological Systems Lens. Sexes, 6(3), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6030052