Abstract

Personal identity is a multidimensional, universal, and ever-developing construct that forms primarily during youth. One domain of identity—gender—manifests quite clearly in terms of developmental course and psychosocial components in the lives of transgender individuals. Members of this population often initiate various social and medical transitions to rework their gendered characteristics to align more authentically with their internal selves. Consequently, healthcare and social service professionals express growing interest in facilitating and fostering the psychological health of transgender youth. Rather than focus on adversity (e.g., depression, suicidality, mental illness), the current study addresses this concern by describing positive components of the gender identity of 120 transmasculine youth participants. To this end, we operationalized gender identity health through three overarching constructs: developmental process, psychological functioning, and the positive outcomes of being a transgender person. Further, we investigate how these components interrelate, plus compare responses by age and gender identity cohorts. For age, we compared adolescent responses to the identity measures to those of transgender emerging adults (n = 166; 20–29 years) and adults (n = 53; 30–39 years). For gender, we partitioned the adolescent participants into binary (n = 91) versus non-binary (n = 29) identities. The descriptive results demonstrated that identity is reasonably developed, functional, and positive in this adolescent sample. Moreover, the three hypothetical components of transgender identity demonstrated modest overlap with each other. The youth did not differ in identity development, functionality, or positivity compared to older cohorts. Binary transmen scored slightly higher on gender authenticity and commitment than their non-binary transmasculine counterparts, but the two gender groups were the same on the other identity components. We discuss some practical implications of these findings as focus areas for healthcare providers and support systems to continue to foster healthy identity development.

1. Introduction

According to eminent youth psychoanalyst Erik Erikson [1], identity development is a lifelong process of self-understanding, and adolescence represents a particularly critical stage. Modern identity research typically examines identity through various domains of life (e.g., career or religious identity). One highly salient yet under-examined domain of identity development is gender. Transgender (or trans; see Section 1.5) people elegantly demonstrate a gender identity synthesis journey described by Erikson [1]. Trans individuals transition their gender roles, characteristics, and labels away from what others presume or expect based on their anatomical sex in favor of adopting and synthesizing a more authentic self-concept of themselves as men, women, or non-binary people (e.g., agender, genderfluid [2]). In the current study, we use the term “transmasculine” to describe those designated as female at birth who transition away from the expectations associated with being female (e.g., femininity, womanhood), to live either as binary trans men or non-binary transmasculine persons.

While experiences specific to transgender self-realization and identity integration have been investigated thoroughly (e.g., [3]), relatively few studies examine gender identity development in trans people through a normative lens (i.e., whereby gender identity, rather than being transgender, is the focal construct). Thus, the current study documents various dimensions of transmasculine adolescents’ gender identities, contributing to a growing effort within the research landscape to depathologize and unite transgender existence with broader theoretical constructs, like Eriksonian identity frameworks.

Many empirical studies have addressed psychopathology and psychosocial vulnerabilities in transgender youth, such as depression, self-harm, and suicidality [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. In contrast, the current study’s investigation of the state of gender identity development, gender identity functioning, and positive trans identity addresses mental health from a more positive orientation. Applying this lens, developing a strong sense of oneself in a given identity domain symbolizes flourishing psychosocial health [14,15,16,17]. This positive orientation fits with emerging research investigating resilience and protective factors that buffer the negative effects of minority stress and enhance transgender well-being (e.g., self-definition and pride, gender affirmation, and community connectedness) [18,19,20]. Correspondingly, developing a positive, functional gender identity should be advantageous for the well-being of transmasculine youth.

1.1. Identity Development

Based on a neo-Eriksonian paradigm [21], identity’s developmental state emerges from three interrelated processes: commitment, in-depth exploration, and reconsideration of commitment. Commitment involves making choices to solidify attachment to an identity and is usually associated with positive psychosocial outcomes (e.g., cutting one’s hair short or changing one’s pronouns to be more masculine to align with identity [22,23,24]). In-depth exploration consists of reflecting on, learning about, and experimenting with identity options (e.g., researching transgender culture or medical transition pathways). When engaged, exploration can feel uncomfortable and ruminative or pleasant and enriching at different times throughout the lifespan [25,26,27]. Reconsideration of commitment involves doubting and relinquishing pre-existing identity characteristics in pursuit of more satisfying options (e.g., moving from a butch woman identity to a transmasculine one). Albeit associating with poor mental health, having reconsidered one’s identity proves to be beneficial in the long run, probably because it signifies thoughtful and agentic self-scrutiny [28,29,30]. In combination, the three identity processes typify developmental states ranging from undifferentiated, detached, and ambiguous to synthesized, firm, and consolidated.

1.2. Identity Functionality

Applying a psychological lens, people develop identities because they confer cognitive and affective benefits. Adams and Marshall [14] theorize five ways that identity aids in information processing and individuation. These dimensions are structure, harmony, goal direction, future orientation, and personal control.

First, identity provides the structure for processing, understanding, and organizing self-relevant information (structure; e.g., knowing one’s gendered pronouns; hence, being able to discount or correct those who misgender/use incorrect pronouns). Second, identity should unite values, beliefs, and commitments to produce a coherent, consistent, harmonious sense of oneself (harmony; e.g., a transmasculine person who believes masculinity fits their identity and is committed to living as a man may wear men’s clothing and use the men’s public restroom). Third, identity directs goals by helping to guide aims or ideals in life (goal direction; e.g., a transmasculine identity prompts the individual to consider if they would like to transition their gender expression to fit their internal sense of identity). Fourth, identity helps orient one to future possibilities (future orientation; e.g., a transmasculine identity could prompt someone to contemplate becoming a father). Finally, identity imparts a sense of agency and control over life (personal control; e.g., exercising control over the degree of medical interventions a transmasculine person desires for their unique gender identity expression ideals). According to theory, identity functions optimally when all five purposes are engaged [31].

1.3. Positive Transgender Identity

Intrinsically related to well-being, positive transgender identity involves feelings of genuineness, fulfillment, and integration of life and values [32,33]. Based on thematic qualitative analysis [34] and empirical factor analysis [35,36], Riggle and colleagues identified self-awareness, authenticity, community, intimacy, and social justice to describe the rewards of or positive components arising from a lesbian, gay, bisexual, and/or transgender (LGBT) identity.

Specifically, self-awareness refers to feeling knowledgeable about oneself. Authenticity means feeling comfortable and genuine in one’s LGBT identity. Community involves perceived belonging to a group of individuals with similar sexual orientation and/or gender identity. Intimacy characterizes sexual closeness, relational insights, and secure romantic and sexual relationships as an LGBT person. Lastly, social justice reflects compassion and advocacy for others. Altogether, these five dimensions represent strengths, resources, and resiliencies indicative of well-being [35,36]. For the current study, we narrow the scope of positive identity from LGBT to simply T: transgender identity.

1.4. Gender Identity as an Overarching and Evaluable Construct

In this study, we conceptualized gender identity as a coherent whole of three facets: development, functionality, and positivity. That is, we operationally define gender identity through three dimensions: First, the developmental processes of commitment, in-depth exploration, and reconsideration of commitment. Second, its psychological purposes of structure, harmony, goal direction, future orientation, and personal control. Finally, its perceived positive qualities, defined through two intrapsychic components (i.e., greater self-awareness and authenticity) and three social elements (i.e., community belonging, interpersonal intimacy, and engagement with identity-related social justice).

For the purposes of this study, wherein we evaluate each of these components, we conceptualize a healthy gender identity as developmentally mature and consolidated, robust in its functioning, and positively self-regarded. While identity researchers could consider development or functionality alone as indicators of a healthy or well-formed identity, and positive psychologists may gravitate toward self-positivity as a proxy for well-being, we attempt to capture different ways people engage with their gender identities as a psychological construct. That is, a construct that purportedly evolves, operates for the individual, and is evaluated reflexively, altogether reflecting its psychological healthiness.

1.5. The Dynamics of Language

Language and labels are dynamic. For example, transsexual, transgenderism, and transgendered were formerly used to describe transgender people, as they are currently labeled [37]. For our entire sample, we espouse the term “transmasculine” to identify people designated female based on visible anatomy at birth but go on to identify as either binary (trans)men or non-binary masculine people. Transmasculine, as an umbrella label, emerges from a broader, more progressive model for gender as a continuum rather than a man-woman dichotomy. Instead of transitioning identity from one binary label to the other, to be transmasculine is to shift the core and stable components of oneself toward masculinity. The transition may apply to numerous facets of life (e.g., desired self-expression or social role) and be partial or total, where binary transmen typically desire a total shift (i.e., binary transmen may strictly consider themselves men). Further, there is no one way to be non-binary; the only criteria we employed to define the population parameters were (a) being declared female at birth (thereby presumed a girl/woman) and (b) feeling that the essence of one’s gender was more masculine, such that portraying their identities most authentically would involve transitioning in some way (e.g., changing name, pronouns, anatomy). We are mindful that, as language evolves, these words may fall out of favor or no longer apply [38]. At present, we are using the best descriptive language available to honor our participants’ range of trans identities.

1.6. The Current Study

The current study combines absolute and relative data to describe transmasculine adolescents in terms of Eriksonian identity theory. Primarily, we aim to present and interpret descriptive information to illustrate the general health of adolescent transmasculine identity within a sample of transmasculine teens. We also examine the associations between the identity constructs using bivariate and canonical correlations. Our secondary aim is to compare gender identity across two distinct quasi-independent sets: age and gender. Considering the somewhat positive sociocultural shifts that may impact today’s trans youth as they seek identity-related information and environments for affirmation, we opted to compare our adolescent participants’ gender identity health to that of some older trans persons [39]. First, we compare adolescents to two older transmasculine cohorts (emerging adults and adults) on psychological gender identity components (i.e., development, functionality, and positivity). Second, considering the potential impact of gender fluidity, we compare binary and non-binary adolescents (i.e., self-identified gender) on the three identity constructs. Altogether, these cross-sectional findings help shed light on the identities transgender youth hold, as well as distinguish what we call gender identity health across age and gender-identity-based groups.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.1.1. Primary Sample

Eligible participants were adolescent transmasculine persons aged 10–19 years selected from a larger respondent pool that was not age-restricted (N = 369). From 130 age-eligible respondents, we eliminated ten cases who only responded to the demographics (i.e., none of the study variables). The primary interest of this study was to describe transmasculine adolescent identity, so the focal volunteer convenience sample comprised 120 participants aged 13 to 19 (mean = 17.28; mode = 18.00 years). Based on these parameters, individuals spent a median of 20 min completing the entire survey. The majority disclosed their transgender identity to someone an average of 3.58 years ago and began their transition 2.01 years ago. Most participants self-described, in a free-response format, as white, pansexual, and binary transmen. The majority were not-at-all to slightly religious, had a mother who completed post-secondary education, were located somewhere in the United States of America, and resided in suburban communities. Generally, the sample was modestly diverse in sociodemographics but relatively homogenous in medical transition (as would be expected with this age group) and quite homogenous in terms of racial composition. Aside from their gender and (potential) sexual minority statuses, in many respects, most of our sample might be considered members of a middle-class majority group. Table 1 contains a demographic and medical intervention overview of adolescent participants. Data completion rates decreased across the three measures, presumably due to survey fatigue. To maximize data per scale, missing data were handled using a familywise-pairwise deletion approach: listwise deletion was applied within instrument families (i.e., all relevant subscales), and pairwise deletion was used across different instruments.

Gender Identity

We divided gender identity into binary-based categories. Three in four youth self-identified as transmen. Transmen were those who indicated they were full-time or completely binary men (e.g., “100% masculine,” “FTM trans man”). The remainder identified as transmasculine individuals; those who suggested they were part-time or partially men (e.g., “Transgender Demiboy,” “My gender is part male and part non-existent”).

Sexual Orientation

There was intricate sexual orientation diversity in the youth sample, with a popular theme of multiple attractions (see Table 1). About half of the youth participants identified as having numerous or poly attractions. Identities like pansexual (e.g., “Pansexual with more attraction to AFAB people [sic]”; AFAB = assigned female at birth), bisexual (e.g., “Bisexual man, leaning towards men”), polysexual (e.g., “I am not attracted to women but to people who describe their gender expression as (partially) feminine”), and gynesexual (e.g., “I’m into vagina”) demonstrated the breadth of a multisexual umbrella. There were also several participants on the asexual spectrum (e.g., “I am a [sic] asexual, polyamorous panromantic”), as well as homosexual (e.g., “gay man,” “same-sex-attracted, lesbian”) and heterosexual (e.g., “straight,” “heterosexual man”) participants. It was not possible to specify the romantic attractions of all asexual participants due to their descriptions lacking detail (e.g., “I am asexual” vs. “bi-romantic asexual man”). Those categorized as homoflexible expressed fidelity to their homosexual attractions while leaving room for other attractions (e.g., “Approx 75% gay man”). Ten participants called themselves “queer,” and one person expressed uncertainty (“I don’t completely know this yet”).

Medical Intervention for Transition

Most participants indicated a desire for hormones (e.g., gender-affirming testosterone), top surgery (e.g., mastectomy), and at least some bottom surgery (e.g., phalloplasty, metoidioplasty, scrotoplasty, hysterectomy). However, most were not currently completing any medical treatments. None of the participants had experienced any bottom surgery. Over three-quarters saw a counsellor for gender-related issues in their lives.

2.1.2. Comparison Groups

We created two age groups to which we could compare our adolescent sample. Out of the total respondent pool, we extracted those aged 20–29 years (n = 166; Mage = 23.70, SD = 2.70; Mdisclosure = 6.36 years ago, SD = 5.59; Mtransition = 3.10 years ago, SD = 3.29) and 30–39 years (n = 53; Mage = 33.53, SD = 2.81; Mdisclosure = 12.26, SD = 10.11; Mtransition = 4.73, SD = 4.54) to represent emerging adults and adults, respectively [40]. These two truncations served as comparison groups for the adolescent sample but were otherwise not involved in our analyses.

Table 1.

Transmasculine adolescent sociodemographic characteristics and level of medical intervention.

Table 1.

Transmasculine adolescent sociodemographic characteristics and level of medical intervention.

| Variable | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 17.28 | 1.39 | |

| Disclosure | 3.58 | 2.74 | |

| Transition | 2.01 | 2.00 | |

| Sociodemographics | n | % | |

| Gender identity | |||

| Transman | 91 | 75.83% | |

| Transmasculine | 29 | 24.17% | |

| Racial identity | |||

| White | 98 | 81.67% | |

| Racialized (People of Color) | 20 | 16.67% | |

| Sexual orientation | |||

| Pansexual | 35 | 29.17% | |

| Asexual | 20 | 16.67% | |

| Homosexual | 17 | 14.17% | |

| Heterosexual | 17 | 14.17% | |

| Bisexual | 16 | 13.33% | |

| Queer | 10 | 8.33% | |

| Homoflexible | 3 | 2.50% | |

| Gynesexual | 1 | 0.83% | |

| Questioning | 1 | 0.83% | |

| Country of residence | |||

| U.S.A. | 70 | 58.33% | |

| Canada | 19 | 15.83% | |

| U.K. | 17 | 14.17% | |

| Europe (Non-U.K.) | 6 | 5.00% | |

| Australasia | 5 | 4.17% | |

| Argentina | 1 | 0.83% | |

| South Africa | 1 | 0.83% | |

| Community type | |||

| Suburban | 50 | 41.67% | |

| Rural | 35 | 29.17% | |

| Urban | 34 | 28.33% | |

| Religiosity | |||

| Not at all | 43 | 35.83% | |

| Slightly | 49 | 40.83% | |

| In-between | 12 | 10.00% | |

| Moderately | 14 | 11.67% | |

| Extremely | 1 | 0.83% | |

| Mother’s education | |||

| No secondary | 1 | 0.83% | |

| Some secondary | 20 | 16.67% | |

| Finished secondary | 19 | 15.83% | |

| Some post-secondary | 23 | 19.17% | |

| Completed post-secondary | 31 | 25.83% | |

| Some/Completed graduate | 25 | 20.83% | |

| Medical transition | n | % | |

| Had gender counselling | |||

| No | 36 | 30.00% | |

| Yes | 84 | 70.00% | |

| Hormones | |||

| No, do not wish to take | 2 | 1.67% | |

| Yes, wish to take but not taking | 86 | 71.67% | |

| Yes, taking | 32 | 26.67% | |

| Top surgery | |||

| No, do not wish to have | 2 | 1.67% | |

| Yes, wish to have but not had | 86 | 71.67% | |

| Yes, had | 32 | 26.67% | |

| Bottom surgery | |||

| No, do not wish to have | 50 | 41.67% | |

| Yes, wish to have but not had | 70 | 58.33% | |

| Yes, had some I desire | 0 | 0.00% | |

| Yes, had all I desire | 0 | 0.00% | |

2.2. Materials

2.2.1. Gender Identity Development

Crocetti and colleagues developed a three-factor model for identity development involving the constructs of commitment, in-depth exploration, and reconsideration of commitment [21,41]. Each construct is a process that contributes to the continual Eriksonian task of synthesizing or maintaining one’s sense of identity within a specific domain, jointly referred to as developing identity. Crocetti, Schwartz, et al. [42] created the Utrecht Management of Identity Commitments Scale (U-MICS) to measure each of the three processes in any identity domain, using statements to which participants respond on a five-point Likert scale (1 = completely untrue to 5 = completely true). As required for use, we inserted “gender” into the generic statements to measure our identity domain of interest.

The commitment scale contains five items and measures how connected and attached individuals feel to their identities (e.g., “My gender gives me security in life”). Exploration contains five items and refers to how informed and self-evaluated individuals are regarding their identities (e.g., “I try to find out a lot about my gender”). Reconsideration comprises three items and refers to how doubtful individuals are about the accuracy or sustainability of their identities (e.g., “I often think it would be better to try to find a different gender”). The instrument’s scales have demonstrated acceptable reliability and validity across multiple identity domains, as it has been used with diverse samples and translated into different languages [41,42,43,44,45,46].

2.2.2. Gender Identity Functionality

Based on existing research, Adams and Marshall [14] summarized five core identity purposes. The more functional the identity, the more meaningful and integrated it is with an individual’s life. The multidimensional Functions of Identity Scale (FIS) contains 15 items distributed equally among five scales to operationalize identity functionality [30,45]. We added a phrase to each item to ensure responses reflected the identity domain of gender, specifically (e.g., “in relation to my gender…”). Participants respond to each item on a Likert scale from 1 = very untrue for me to 5 = very true for me.

Structure defines the ability to support the interpretation and organization of self-relevant information (e.g., “In relation to my gender, I am certain that I know myself”). Goal direction refers to the creation and self-directed achievement of personal aims (e.g., “With regard to my gender, I have constructed my own personal goals for myself”). Harmony signifies coherence between values, beliefs, and actions (e.g., “My values and beliefs fit with my gender”). Future orientation describes identities that support the individual in envisioning their life to come (e.g., “I am clear about who I will be in the future in connection to my gender”). Finally, personal control addresses a sense of agency exercised to attain goals and align values and beliefs with actions (e.g., “In terms of my gender, I am self-directed when I set my goals”). The scales typically produce reliability scores above α = 0.80 [47,48,49].

2.2.3. Positive Transgender Identity

A positive view of oneself meaningfully connects to psychological well-being [33], representing a desirable outcome for identity development. Based on Riggle et al. [36], we employed a modified Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Positive Identity Measure (LGB-PIM or PIM), replacing the term “LGBT” with “gender identity” or “trans.” The PIM contains five 5-item scales, each measuring a unique dimension of positive identity. Items are rated on a Likert scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree.

Self-awareness involves how identity leads to knowledge about oneself (e.g., “My gender identity leads me to important insights about myself”). Authenticity defines comfort and a sense of truth about one’s identity (e.g., “I am honest with myself about my gender identity”). Community references a sense of belonging and involvement with others (e.g., “I feel a connection to the trans community”). Intimacy encourages sexual liberty and connection (e.g., “My gender identity allows me to be closer to my intimate partner[s]”). Finally, social justice is the belief that one’s identity leads to an awareness and concern for other forms of oppression and advocacy (e.g., “My experience with my gender identity leads me to fight for the rights of others”). The instrument has been used in English and Italian samples and correlates with measures of psychological well-being, supporting its use as a proxy or precondition for healthy identity development [33,50,51].

2.3. Procedures

We solicited voluntary participants through closed online forums for transgender persons assigned female at birth. An online survey via SurveyMonkey presented an information letter, consent form, and the study measures. In fixed order, the survey contained the U-MICS, PIM, two measures external to the current study, and then the FIS. Apart from the potential for the demographics to serve as identifying information, all survey participation was completely anonymous. Respondents were encouraged to share the survey with other eligible persons (e.g., snowballing recruitment), meaning our data was from a convenience sample. Interested respondents could enter a random draw for a gift card valued at $20 (CAD) as remuneration. We awarded three prizes following data completion. We concluded by providing a feedback letter listing contacts for research inquiries and mental health crisis support. The Office of Research Ethics at the University of Waterloo approved this study (protocols #21798 and #44452). We assessed data integrity by examining time to completion, the proportion of measures completed, and response patterns (e.g., uniform responding), in line with established quality control practices.

Although the recruitment materials indicated that participants were to be 18 years of age or older, several minors nonetheless completed the survey. Upon identifying that individuals aged 13–17 had voluntarily participated using the adult consent process (i.e., without parental consent), we immediately reported this issue to the institutional review board. Following review, the board granted approval for the inclusion of the anonymous data provided by these underage participants (protocol #21798).

3. Results

3.1. Goal 1: Evaluating the State of Gender Identity in Trans Youth

3.1.1. Variable-Centered Observations: Descriptive Statistics

To address the state of gender identity within our sample of trans youth, we present descriptive statistics outlining the absolute levels of gender identity development, functionality, and positivity. Table 2 contains the means, standard deviations, and internal consistencies of these gender identity components assessed in the current study. All average responses across all identity measures were above the scale midpoint, with one exception (i.e., U-MICS reconsideration of commitment).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and internal consistency of identity health indicators.

Gender Identity Development

Most adolescents reported they explored their gender identities (e.g., reflected on, researched), with 74.90% of scores on this scale being above the midpoint (indicating exploration was “true for me”). On average, participants indicated relatively positive levels of gender identity commitment (i.e., their gender identity provided them with security and confidence). That is, 73.30% of adolescents endorsed commitment. On average, participants indicated that the reconsideration construct did not resonate for them; this means that they tended to say that it was untrue that they were searching for another gender or that life would improve if they had a different gender. Almost all (95.00%) participants indicated that the reconsideration items (e.g., “I often think it would be better to try to find a different gender”) were untrue for them. At the individual level, when identity is a combination of relatively elevated in-depth exploration and commitment scores with low levels of reconsideration of commitment, it is considered an achieved identity [21]. Relative levels of each identity development process can typologically depict developmental status (viz., diffusion, moratorium, searching moratorium, early closure, or achievement [22]). Achievement represents a satisfying and beneficial identity status reflecting strong and informed self-understanding.

Identity Functionality

On average, participants indicated that all functions of identity scales (i.e., structure, harmony, goal direction, future orientation, and personal control) felt true. Over 84.00% of participants had identity functionality scale scores above the midpoint (i.e., 87.40% structure, 90.40% harmony, 90.30% goal direction, 89.29% future orientation, 84.50% personal control). Moreover, over one-quarter of the scores were the highest possible on structure, goal direction, and future orientation (i.e., completely agree on every item). However, it is noteworthy that approximately two-thirds of participants completed this instrument in sharp contrast to the volume that completed the U-MICS (96.90%) and the PIM (93.00%). This attenuation is probably due to the placement of the FIS at the end of the survey (i.e., survey fatigue), given that other instruments toward the end of the survey also suffered from similarly lower response rates. We consider the implications of this attrition in the section for limitations and recommendations (see Section 4.5). However, we suspect that the attrition was random and bore no systematic effect on our results, as Chi-square analyses revealed that FIS attrition for adolescents, emerging adults, and adults did not differ. One important consideration for these results was the particularly low internal consistency for personal control, limiting our interpretations of participants’ behaviors on this construct.

Positive Transgender Identity

In terms of positive identity, scores were similarly high overall. Adolescents endorsed the social justice scale the most highly, with over one in five respondents agreeing completely that their gender identity has made them feel more aware and invested in trans issues (i.e., selecting the ‘strongly agree’ response for all five items measuring social justice). On average, more than nine in ten adolescents agreed that their gender identity provided them with self-awareness, feelings of authenticity, and a sense of social justice. Eighty-one percent (81.20%) of youth agreed that they felt connected to the trans community—characterized by feeling visible, included, and supported. The high endorsement of these scales indicates a strongly positive trans identity by adolescents. However, we observed the lowest PIM average on intimacy, with an average rating at the midpoint (neither agree nor disagree). Over half (57.20%) of adolescents had intimacy scores near the scale midpoint (i.e., 3.00–5.00 on the 1–7 scale), signaling low endorsement of their gender identities’ utility for sexual communication, freedom, and mastery with intimate partners. However, more youth agreed/strongly agreed (23.10%) than disagreed/strongly disagreed (12.80%) with this intimacy scale. This distribution of non-neutral responding indicates that our adolescent sample demonstrated quite variable self-perceptions that tend to be more positive in frequency, but if negative, are intense.

3.1.2. Inter-Scale Correlations

Because we have conceptualized gender identity through three constructs, we examined their interrelations using bivariate and multivariate correlations. We contend that development, functionality, and positivity define unique and different aspects of the overarching construct of gender identity. Correlations address the contention of uniqueness and overlap of these theoretical constructs.

Zero-Order Relationships

Pearson r correlation coefficients revealed generally weak-to-moderate associations between all measures (see Table 3). The U-MICS scales exhibited low or no intercorrelations. The FIS dimensions intercorrelated somewhat strongly (rs = 0.30 to 0.69), suggesting these scales are not unique but interdependent or exhibit some undesirable multicollinearity. Finally, the PIM scales were not-at-all to modestly correlated (rs = 0.10 to 0.41), whereby self-awareness and intimacy showed consistent correlations with the other PIM scales (rs = 0.20 to 0.41 and 0.10 to 0.41, respectively). Overall, adapted scales behaved as expected, suggesting that their adaptation to measure gender identity was successful (one exception might be made for personal control, based on its internal consistency).

Table 3.

Correlations among all gender identity-related scales.

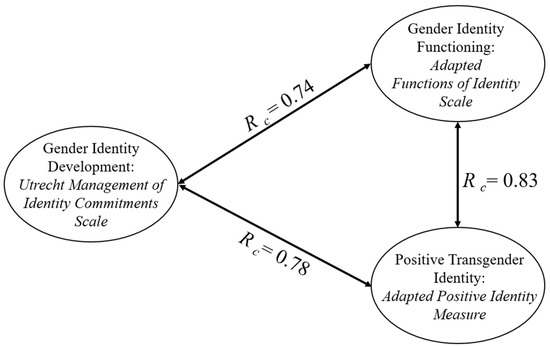

Canonical Correlation

Interpreting the numerous zero-order relationships between the various scales, presented in Table 3, is somewhat daunting. Moreover, zero-order correlations do not demonstrate how the latent identity constructs interrelate. To this end, Figure 1 presents how the sets of identity variables (development, functionality, positivity) relate to each other as multivariate wholes using canonical correlation analyses. This allowed us to examine the maximal shared variance between any combination of one set (e.g., the three U-MICS subscales) and another set (e.g., the five PIM subscales). Canonical correlation analysis produces a value of Rc, which is analogous to the Multiple R in multiple regression analyses. In multiple regression, a Multiple R represents the maximized multivariate relationship between a set of variables and a single variable. By extension, canonical correlation analysis computes a maximized relationship between linear combinations of two sets of variables. Inspection of Figure 1 indicates strong canonical correlations between the three constructs (Rcs = 0.74 to 0.83). For each set of correlations (i.e., between the U-MICS and PIM, U-MICS and FIS, and FIS and PIM), only the first two functions were significant. Appendix A contains interpretations of the two functions underlying each canonical correlation; Table A1, Table A2 and Table A3, with the accompanying descriptions, provide the interested reader with a breakdown of the canonical variates underpinning each Rc.

Figure 1.

Canonical correlations between gender identity development, gender identity functioning, and positive transgender identity.

3.1.3. Summary of Observations

Overall, our sample of trans adolescents demonstrated elevated levels of identity development, whereby low reconsideration scores, as observed, contribute inversely to healthy identity when achievement and exploration are high [22]. Gender identity functioning was also favorable, with all scales rated highly, marking a healthy ego identity [14]. Finally, participants in our sample expressed highly positive self-attitudes as transgender people across four of five domains, excluding intimacy.

3.2. Goal 2: Comparing the State of Youth Gender Identity by Age and Gender

3.2.1. Age Comparison

Comparing the adolescents to emerging adults or adults who participated in the same study suggested there were, generally, no differences in gender identity (i.e., development, functionality, or positive transgender identity) between the three age groups with either time since transition onset (TST) or time since initial disclosure (TSD) as covariates. One exception in each model was a weak multivariate effect of age cohort on positive transgender identity (with each covariate, FTST(10, 610) = 2.53, p ≤ 0.01; FTSD(10, 620) = 1.90, p < 0.05). Partial eta squared values indicate that these effects were very weak (ηp2TST = 0.04; ηp2TSD = 0.03).

Inspection of the univariate effects suggests that there were effects of age on PIM social justice, with both time since transition onset and time since initial disclosure as covariates. With time since transition onset as a covariate, adolescents (Mestimate = 6.01, SE = 0.09 [CI: 5.83, 6.12]) and emerging adults (Mestimate = 5.93, SE = 0.08 [CI: 5.78, 6.09]) each scored higher than adults (Mestimate = 5.64, SE = 0.14 [CI: 5.27, 5.81]) but did not differ from each other, FTST(2, 309) = 4.12, p < 0.05, ηp2 = 0.03. Similarly, with time since initial disclosure as a covariate, the univariate effect was such that adolescents (Mestimate = 6.04, SE = 0.09 [CI: 5.86, 6.23]) and emerging adults (Mestimate = 5.94, SE = 0.08 [CI: 5.79, 6.10]) scored significantly higher than adults (Mestimate = 5.50, SE = 0.14 [CI: 5.21, 5.79]), FTSD(2, 314) = 4.70, p ≤ 0.01, ηp2 = 0.03).

There was also a weak effect of age on the community belonging component of positive identity for both covariates, FTST(2, 309) = 4.53, p < 0.05, ηp2 = 0.03; FTSD(2, 314) = 2.52, p < 0.05, ηp2 = 0.02. Across the time since transition onset and time since first disclosure models, adolescents (Mestimate = 5.06; 5.08, SE = 0.13; 0.13 [CI: 4.80, 5.32; 4.81, 5.34]) felt more a part of the trans community relative to the adult cohort (Mestimate = 4.50; 4.35, SE = 0.21; 0.20 [CI: 4.09, 4.92; 3.96, 4.74]). Emerging adults did not differ from either group (Mestimate = 4.78; 4.76, SE = 0.11; 0.11 [CI: 4.56, 5.00; 4.53, 4.98]).

These small effects are likely unstable. Table A4 in Appendix B contains the results of the largely non-significant multivariate analysis of covariance tests and facilitates a comparison between the two covariate models. In short, the age group did not produce differential effects on the gender identity variables. All effect sizes were very small, and most tests were not significant.

3.2.2. Gender Comparison

Emerging narrative research seems to portray the experience of identity formation in non-binary youth as unique [52,53]. Thus, we consider it possible for identity constructs to differ systematically between non-binary and binary trans youth. To test for statistical differences as a function of gender binarity, we conducted independent samples t-tests with Bonferroni-adjusted p-levels for each of the 13 transgender identity constructs. The tests revealed a significant and large effect of gender identity on U-MICS commitment, t(118) = 3.02, p = 0.003, Cohen’s d = 0.64, such that transmen (M = 3.72, SD = 0.71) exhibited higher commitment than non-binary transmasculine persons (M = 3.25, SD = 0.77). There was also an effect of PIM authenticity, t(115) = 3.32, p = 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.71, whereby transmen (M = 5.92, SD = 0.89) demonstrated greater authenticity than non-binary transmasculine persons (M = 5.26, SD = 1.00). Tests for exploration, reconsideration, structure, harmony, goals, future, control, self-awareness, community, intimacy, and social justice did not reach significance as a function of gender binarity (see Table A5).

4. Discussion

In the current investigation, we aimed to examine overarching gender identity in a sample of transmasculine youth. Using measures of gender identity development, gender identity functionality, and transgender self-identity positivity, we assessed the absolute levels of each variable across participants and then the relationships of the three gender identity domains through correlational analyses. Finally, we employed comparative tests to examine differences by age and gender cohorts. Overall, what we found was quite positive. While gender identity development is presumably most tumultuous or irregular in adolescence, the young transmasculine persons who participated in this study did not generally convey gender identity crises or passivity. Our results overarchingly illustrate that transmasculine youth tend to construct sophisticated and rewarding gender identities.

4.1. Goal 1: Evaluating the State of Gender Identity in Trans Youth

Our sample of adolescents expressed gender identity development characterized by Crocetti [22] and Marcia [16] as the most consolidated and optimal identity status, “achieved.” The fact that the youth in our study generally presented achieved gender identities implies their success in constructing strong (represented by high commitment and low reconsideration) and informed (represented by elevated exploration) self-understandings. In various domains, identity achievement coincides with strongly positive life characteristics, including openness to experiences, life satisfaction, positive affect, and lack of negative affect, as well as fewer problem behaviors and more optimism (or positive reappraisals) [45,46,54,55]. In addition, the high levels of commitment and exploration coupled with low reconsideration found in our sample of trans youth are consistent with research showing that identities synthesized in adolescence tend to be maintained actively rather than deconstructed or left stagnant [24,56,57]. The fact that the three identity development constructs were weakly correlated or uncorrelated affirmed that the processes underlying gender identity development are unique and independent [41].

That our sample demonstrated consistently high scores on identity functionality further illustrates the remarkable maturity of their gender identities by adolescence. Transgender youth participants showed strength in three key areas: (1) processing and integrating self-relevant information (structure), (2) setting personally meaningful identity-related goals (goal direction), and (3) clearly envisioning future possibilities aligned with their gender identities (future orientation). These results likely reflect the demands of undergoing a gender transition, which often requires a well-organized sense of self, a goal-oriented mindset, and ideals for the future. Moreover, transitioning typically involves proactive steps and intentional planning, rooted in one’s values and self-concept. Indeed, the nuanced and complex insights transgender individuals exhibit regarding their gender identities in an often gender-stigmatized world fit with our results. For example, trans folks report resisting “transnormativity,” a concept defined by Johnson [58] as describing alternative hegemonic expectations for trans identity development and expression that ostensibly legitimize (or invalidate) individual transness (e.g., a truly transgender person should desire both top and bottom surgery) [59]. For trans persons to subvert or negotiate with imposed boundaries around what makes them valid demands profound introspection that could inform their personal identity convictions [59]. Additionally, qualitative studies emphasize the impressive maturity and self-insights of transgender youth through concepts such as viewing gender creatively and fluidly, and using self-expression as a form of advocacy, protest, or even artistic expression [60,61,62].

It is important to note that the relatively high intercorrelations among the identity functionality scales recontextualize our speculations and conclusions; these correlations suggest the identity function constructs may overlap conceptually. Correlations among identity function measures were higher in the current study than those in Demir [49], perhaps because of the specific wording we employed to emphasize gender identity functioning. Confirmatory factor analysis by Crocetti, Sica, and colleagues [48] suggests the FIS factor structure may overlap—ergo the constructs may not be distinct (cf. Demir [49]). Thus, we suggest the psychometric properties of the Functions of Identity Scale be investigated further, and we advise caution against using the current personal control scale in future research, based on its limited internal consistency. Within this cautionary note, we make room for the possibility that it could be difficult to capture personal control in adolescents with respect to gender identity. It is likely that youth undergoing any gender transition feel partially limited by their status as minors or “children”. Whether it be at the doctor’s office awaiting approval for hormones, in the classroom hoping for a teacher to revise an attendance sheet with a name change, out shopping with a parent for gender-affirming clothes, etc., adult authority figures often gatekeep access to trans youths’ gender-related desires and aims [63,64]. For this reason, it is possible that the items used to measure a gender identity-related sense of agency fail to tap what truly underlies this construct in young transgender people.

Lastly, and congruent with development and functionality, positive identity tended to be rated highly across most scales. The results showed that trans youth in our sample viewed their identities as highly conducive to self-awareness, authenticity, and community. Most distinctly, their gender identities fostered interest in social justice.

In contrast to the other positive identity indicators, adolescents did not express the thriving benefit of their gender identities for understanding and expertise in intimate relationships. Initially, we thought a lack of intimacy was unsurprising given that teenagers tend to postpone sexual involvement [65], and trans youth report less sexual activity than national youth samples [66,67]. However, intimacy scores did not change across age groups (see Section 3.2, Goal 2). One possible explanation is that the high proportion of asexual-identified respondents (i.e., those reporting limited or conditional sexual attraction) in our adolescent sample may have lowered the average intimacy score, given its lesser relevance for this subgroup. Theoretically, at least a portion of identity is tethered to how others see and consequently treat us (e.g., through gender affirmation). One can reason that, more than with any other PIM construct, this other-oriented aspect of identity is enacted most clearly in sexual and romantic (i.e., intimate) relationships. Thus, given its importance, it makes sense for those poorer on intimacy to rate themselves relatively lower on self-awareness, authenticity, and community, concomitantly (cf. a transmasculine person who feels seen and affirmed by intimate partners may thus feel validated in their self-conception as a transmasculine person, in turn bolstering their gender-related self-awareness and authenticity).

4.2. Goal 2: Comparing the State of Youth Gender Identity by Age and Gender

4.2.1. Adolescent vs. Emerging Adulthood or Adulthood

By and large, there were very few differences between the transmasculine youth and their older counterparts on any of the gender identity constructs examined herein. No dimension of gender identity development nor identity functionality varied by age group. As the values for each construct remained high in each group, this finding may illustrate that, while adolescence may be the definitive period for identity formation, it is also a lifelong process according to neo-Eriksonian theory. Alternatively, because our study solicited transgender persons who felt they could speak about their gender identities, perhaps we were more likely to recruit individuals with clearer self-perceptions at all ages. Notwithstanding, this null finding raises the question of what can differentiate identity development and functionality. Unlike career and educational development, no specific period or environment promotes questioning or self-constructing one’s gender identity (cf. work or school [68,69]). Instead, we reason that factors like exposure to gender diversity or trans-related information may better differentiate identity-related outcomes for transgender people. For example, Kia et al. [70] present the salience of transgender and gender-nonconforming peer support in facilitating a trans individual’s consideration for their own gender identity development.

Two aspects of positive transgender identity, community and social justice, differed by age cohort. Contrary to expectations, adolescents endorsed belonging to and advocating for the transgender community more strongly than adults but not emerging adults [71]. However, the fact that these findings explained minimal variation in the data may indicate the effect was a methodological artifact arising from recruiting participants online, as young people in particular tend to engage with transgender peers and issues [72,73]. For example, nearly three-quarters of our adolescent sample reported receiving counselling connected to their gender identities, a pattern suggesting our younger participants have discussed transgender issues with at least one mentor or caregiver figure in their lives. The fact that self-awareness and authenticity do not differ by age group points to the stability of transmasculine gender identity commitments made or maintained in adolescence.

4.2.2. Binary vs. Non-Binary Gender

Two scales differentiated binary and non-binary trans youth: commitment and authenticity. We attribute the lower commitment scores exhibited by non-binary transmasculine participants to reflect the potential ambiguity, fluidity, or nihility of many non-binary identities. For example, the often iterative and fluid (not fixed) nature of non-binary gender identity may reduce commitment to any concrete self-definition relative to binary transgender folks simply because identity will fluctuate [74]. Or, for those with neutral or void gender identities (i.e., those who do not identify as masculine, feminine, androgynous, etc.), perhaps the language around commitment fails to capture their experiences forming a strong and stable yet agender sense of self. This notion of inapplicable schemas or language seems consistent with how some youth navigate gendered sexual dynamics as transgender people: “there are no limits and I feel that also makes it hard to come up with ideas of what to do” ([75], p.7). Similarly, as non-binary people develop their identities unconventionally (in a society favoring sex-linked and binary gender), identity commitments may be more obscure than our measures could assess.

Moreover, we considered two possibilities to explain why non-binary persons demonstrated lower authenticity than binary transmen despite producing equivalent scores on identity development and functionality. The first is that non-binary youth may feel an imposter-like inadequacy in their self-identities relative to their binary peers, arising from pressure to conform to a bio-essential and medicalized narrative that says being trans requires feeling “born in the wrong body” and seeking medical interventions to reconcile gender discordance [61]. Moreover, as non-binary individuals are more likely to be affected by experiences of non-affirmation, the invalidation of their identities could attenuate ratings of authenticity given that its measurement (viz., items 6 and 8 in the FIS) involves feeling capable of being open and at peace with their genders [76]. A second explanation is that, because of its fluidity, ambiguity, and variability, non-binary gender authenticity may be a less straightforward and defined concept relative to binary gender authenticity [77]. Nevertheless, gender identity health did not appear to differ by gender binarity in our adolescent sample.

4.3. Theoretical Implications

We conceptualized gender identity as a combination of development, functionality, and positivity. The canonical correlations between all three multidimensional constructs demonstrate their interdependence. These results are congruent with the idea that self-identity includes evaluative and affective considerations [78,79]. Accordingly, gender identity’s evolution interrelates with perceptions about its efficacy for navigating life and appreciating oneself. For example, forming a transmasculine identity may help an individual envision a future as a father that spurs them to advocate for trans parental recognition. From their advocacy, the individual can gain relevant insights and appreciate goodness linked to their trans identity, illustrating the interplay between future orientation, in-depth exploration, and social justice. Essentially, assessing gender identity begs an answer to three interdependent questions: “Who am I?” “What does this enable in my life?” and “How do I feel about myself?” The reciprocal nature of these components merits consideration in future self-identity research.

Theoretically, this study does not examine the origins of gender identity—specifically, how identity is formed or shaped over time. Sexual and gender identity development is understood to occur through developmental processes [16,22]. While we assessed identity status—thereby centering trans and non-binary teens within this framework—we did not explore the contextual, interpersonal, or structural factors that may have contributed to participants’ current identity positions. For instance, Ben-Lulu [80] explores the convergence of gender, religion, and cultural identity among trans individuals, highlighting the richness of intersectional identity and the value of communal markers of inclusion. Future research could draw on additional theoretical models to understand the mechanisms and pathways underlying gender identity formation in trans youth better. Galbraith [81] strongly challenges traditional queer coming-out models and advocates for integrating communal and structural dimensions alongside individual-level developmental components, highlighting several promising directions for theoretical expansion. There remains a clear need for continued theoretical and empirical work to understand the identity trajectories of trans and non-binary youth.

4.4. Practical Implications

A staggering amount of literature focuses on psychosocial vulnerabilities within trans youth [82,83,84,85]. However, high scores on gender identity development, functionality, and positivity, which remain elevated across older age cohorts, illustrate resilience and potential benefits of forming a transgender identity. In response, we offer clinicians tangible recommendations to lean into their transgender clients’ psychological strengths.

In a clinical setting, practitioners might be able to use scores on the U-MICS, FIS, and PIM to facilitate a deeper discussion about the current state of a client’s gender identity. These scales partition identity’s roles and rewards into meaningful components for assessment and offer new language surrounding the developmental processes, purposes, and positive aspects of a marginalized identity. While the three instruments from this study are not assessment tools, evidence for their validity and reliability may translate well for clinical applications, especially for the LGB-PIM, where one study demonstrates its utility within a veteran clinical sample [86]. This suggestion coincides with the work of Clements and colleagues [87], who demonstrate that emphasizing positive transgender identity can strengthen well-being in this population, as well as research pointing to the psychological benefits of supporting identity development for gender and sexual minority youth [88].

On the note of affirming and engendering hope for transgender clients, it appears that transmasculine identity is exceptional for (1) structuring a self-framework for understanding self-relevant information, (2) directing an individual toward their desired goals concerning gender, and (3) orienting attention toward future possibilities and opportunities connected to gender identity. Care providers may make use of these strengths by connecting other treatment aims with the transgender individual’s identity ideals and goals. For example, a young transgender client experiencing persistent disordered eating may feel more motivated to engage in treatment protocols if the clinician reminds them that improving their physical condition will make them eligible for the medical interventions they desire (i.e., meeting weight requirements for surgery, a potential identity-related goal). In general, recontextualizing therapy in terms of a transgender client’s identity may enhance their connection to interventions, potentially improving prognoses for other mental health concerns and providing opportunities for transgender people to appreciate further the ways their identities serve them in life. Indeed, research suggests that a gender-affirmative approach to eating disorder treatment for gender minority folks could be imperative for positive outcomes [89].

Furthermore, fostering a positive orientation in clinical settings with trans clients could involve highlighting the benefits of trans identity, such as enhanced self-awareness, sincere authenticity, and social justice interest. For example, providing outlets or pathways for trans-related advocacy and involvement may further support the identity development [26] and well-being [90,91] of transgender clients. These outlets could be local peer support groups, gender-sexuality alliances, and even online social groups focused on transgender and sexual minority issues. We recommend that clinicians emphasize the positive aspects of trans identity such that clients acknowledge their inner strengths, especially as a tool for resilience (i.e., identity pride) against transnegative social stigma that may become noticeable as the individual progresses through their transition [92]. This suggestion combines the current findings with existing research by Barr et al. [71], who found that strong transgender identity relates to well-being through community belongingness, and Doyle et al. [93], who demonstrate that a clear and strong trans identity can be protective against the negative psychological impacts of discrimination. At the highest level, our suggestion for more competent and identity-affirming clinical care coincides with growing efforts made by scholars like Ghosh [94].

In terms of therapeutic support for potential identity-related complaints in trans youth clients, the current study revealed that adolescents are less likely to endorse mastery and self-perceived comfort with intimacy in romantic and sexual relationships. Beyond the normalcy of intimate inexperience at younger ages, transgender youth may not know how to integrate their gender identities with sexual and romantic roles and behaviors, which may contribute to increased vulnerability to negative sexual or relationship experiences [95]. Despite this notion, levels of intimacy did not differ between age cohorts. One preventative strategy and general recommendation based on our findings is trans-inclusive and progressive psychosexual education to improve the benefits associated with developing a transgender self-identity. Not only would redesigned sexual health education be more comprehensive, but it could also support the integration of trans individuals’ identities with their sexual identities by deconstructing binary thinking that may no longer hold meaning to a person who transcends cisgender notions of sexual orientation [96].

Overall, our findings signal support for gender-affirmation in healthcare and education. Transmasculine adolescents who we might consider affirmed in their identities exhibited strong identity synthesis and positivity, suggesting that providing youth with the space and resources to fully realize their gender identities contribute to their psychological well-being. Our findings coalesce with recent clinical research that gender-affirming care is associated with improved mental health [11,12].

4.5. Limitations and Recommendations

We must interpret these findings in the context of the study’s limitations. First, our sample contained predominantly white, middle-class, North American participants because the research design employed an online convenience sample recruitment strategy [97]. A more diverse sample would be desirable for generalizability and allow for intersectional analyses (e.g., race, socioeconomic status, and ability). Indeed, intersectional minority status poses a unique set of challenges and life experiences that can influence one’s perspective on identity. For example, Black transgender people, especially those under age 35, are disproportionately killed by acts of violence in the United States [98], which may complicate how developing one’s gender identity might be viewed. Indeed, being an ethnoracial minority is associated with reports of transgender-related discrimination [99,100], pointing to the possibility for intersecting minority statuses to interact with or attenuate the positivity of the current findings, if considered in the future.

Further, the current study was cross-sectional, comparing constructs in a snapshot of time across discrete age and gender-based groups. Hence, the current study findings do not suggest whether gender identity health is stable year-to-year. In the future, longitudinal research following a cohort from adolescence into adulthood could document the change, growth, and predictive ability of the three identity constructs, particularly whether the high levels of identity health observed are maintained and what factors (e.g., transition milestones or social support changes) influence their self-ratings. Additionally, the current study mostly focused on intrapsychic self-reflection. A broader perspective considering how issues like sociopolitical context and minority stress impact gender identity development, functioning, and self-perception is a worthy interest area that could test the ecological validity of our findings. Researchers can also replicate the current study with a sample of trans participants experiencing layered marginalized identities to see if the descriptive positivity and age cohort insensitivity remain stable.

In terms of measures, we experienced higher attrition rates for the Functions of Identity Scale, localized at the end of the study survey. Although we did not identify specific factors distinguishing those who completed versus neglected the scale, we are mindful that data on gender identity functionality was overall less representative than both gender identity development and positive transgender identity. To mitigate potential order or fatigue effects, we recommend that researchers counterbalance exposure to study measures, wherever feasible.

Relatedly, the adapted FIS scale for personal control (perceived agency over gender identity-related goals) exhibited questionable internal consistency, indicating that the findings pertaining to this variable should be interpreted cautiously. In a similar vein, the trans-focused PIM scale for intimacy may not apply readily to those in our study with limited romantic and sexual experiences or interests, such as youth with no intimate partnership history and some with asexual spectrum identities (e.g., sex-repulsed asexual individuals). In short, despite generally positive reliability, readers should interpret all measure scores appreciating the possibility that the measure’s psychometric robustness and relevance to our participants could have varied based on their life experiences.

Furthermore, because we found lower authenticity, reconsideration of commitment, and commitment expressed by non-binary participants relative to binary ones, we feel it might be important to recommend adjustments to measurement language to capture the specific and individual identities that non-binary individuals hold. Measuring concepts like authenticity, reconsideration of commitment, and commitment might conflict with the nature of non-binary identity when it is ambiguous or fluid but not necessarily underdeveloped. Researchers might need to adapt or create unique measures that better reflect the nuances of non-binary identities such that they are not mislabeled as immature or unclear relative to more fixed and binary identities.

This study narrowly examines a highly personal aspect of transgender existence—identity. Because we solicited participation from transgender-focused social media groups, our participants had probably synthesized clear senses of their transgender identities prior to completing our study. Consequently, a positive response bias might be present whereby those with less developed transgender identities who may also possess internalized stigma or experience barriers to self-identifying as trans were excluded from the participant pool. These individuals could have produced substantial differences between the groups if included in our analysis. Where the current findings might have illustrated a best-case scenario, gathering data from general youth channels or from individuals who may not yet fully understand or accept their (trans) gender identities may differentiate the sample between age groups.

Similarly, our positive approach to the data introduces some potentially biased language around transgender identity, whereby we frame our results through the common strengths rather than emergent deficits in youth trans identity. While we feel our language is parsimonious and method-appropriate, highlighting this effect tempers our conclusions.

5. Conclusions

By investigating the properties of gender identity—operationally defined as identity development, functions of identity, and positive transgender identity—in a sample of transmasculine youth, the current study contributes to a growing body of research highlighting strength and resilience within this population. Transgender existence is vast and heterogeneous, yet trends towards developed, functional, and positive self-identities as early as adolescence. Moreover, gender identity does not appear to desist, become less efficacious, or become viewed in a less positive light at older developmental stages, apart from a sense of community with other trans people, which is strongest for younger age cohorts. Similarly, the properties of gender identity across binary and non-binary groups do not differ, except for authenticity. Overall, the present findings suggest that transgender people lead diverse yet fulfilling lives. In line with the findings, we encourage practitioners to collaborate with transmasculine youth to hone their identity strengths (viz., envisioning and achieving ideals, harnessing self-knowledge, supporting advocacy interests) as tools for resilience.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.J.R. and A.S.d.R.; methodology, B.J.R.; formal analysis, B.J.R. and A.S.d.R.; data curation, A.S.d.R.; writing—original draft preparation, B.J.R. and A.S.d.R.; writing—review and editing, B.J.R. and A.S.d.R.; funding acquisition, B.J.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Part of this work was supported by St. Jerome’s University under faculty research grant IRG430.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Office of Research Ethics at the University of Waterloo approved this study (protocols #21798 06/10/2017 and #44452 07/02/2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Participants of this study were not asked for permission for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data are not available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| U-MICS | Utrecht Management of Identity Commitments Scale [34] |

| PIM | LGB Positive Identity Measure [29] |

| FIS | Functions of Identity Scale [24] |

| TST | Time since transition onset |

| TSD | Time since initial disclosure |

Appendix A. Canonical Correlation Function Interpretations

Appendix A.1

We conducted three canonical correlation analyses to explore the multivariate relationships between the gender identity constructs in our sample of transmasculine youth. We created three synthetic/latent variables: (1) gender identity development using responses from the Utrecht Management of Identity Commitments scale, (2) gender identity functionality using responses from an adapted Functions of Identity Scale, and (3) positive transgender identity using responses from an adapted (Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual) Positive Identity Measure. To adapt the measures, we inserted phrases like “in reference to my gender” to reflect identity only in the domain of gender.

Appendix A.1.1. Gender Identity Development (U-MICS) and Positive Transgender Identity (PIM)

The canonical correlation analysis between the U-MICS (three scales) and PIM (five scales) yielded three functions with squared canonical correlations of 0.41, 0.29, and 0.07, respectively. Across all functions, the full model was statistically significant (Wilks’ Lambda = 0.39, F(15, 301.30) = 8.06, p < 0.001). Based on the Wilks’ Lambda statistics, the full model effect size was 0.61; this means that, for the set of three functions, the two sets of variables share 61.00% of variance (equivalent to Rc = 0.78). Aside from the first function (Function 1 to 3) being significant (i.e., same as overall model, F(15, 301.30) = 8.06, p < 0.001) and accounting for 40.64% of the variance, the second function (Function 2 to 3) was significant, F(8, 220) = 6.25, p < 0.001, and accounted for 28.72% of the shared variance between the variable sets. Function 3 explained an insubstantial amount of variance (i.e., less than 7%).

Table A1 presents the standardized canonical function coefficients and structure coefficients for Functions 1 and 2 for the U-MICS and the PIM. Also presented are the squared structure coefficients (i.e., representing relative contribution to the function; a structure coefficient of ±0.45 is noted) are also given as well as the communalities (h2; those above 45% are noted) across the two functions for each variable. These metrics demonstrate, overall, the relative importance of the variable to the overall construct across the two functions in the calculation of the canonical correlation. Inspection of Table A1 indicates that PIM authenticity and self-awareness and U-MICS commitment and reconsideration of commitment were primarily responsible for the first function. This first function might reflect a focus on positive identity and the self; that is, authenticity and self-awareness items were defined by “me” statements, while the other PIM scales involve others (i.e., the self in relation to community members, intimate partners, and advocating for groups). Accordingly, a cornerstone of Eriksonian identity development is differentiating oneself in relation to others such that an adolescent espouses peer relationships and social involvement to extract meaningful ideas and opinions that shape personal identity [15]. In the first function, the identity scales of commitment and reconsideration of commitment are most relevant, perhaps because they allow for stability and yet growth or flexibility in identity development [16,22]. The second function was mainly a result of social justice, self-awareness, and community PIM scales with the in-depth exploration U-MICS scale. Perhaps exposure to others by being a part of the trans community or by getting involved in social justice activities motivates exploring one’s identity. Indeed, Crocetti, Jahromi, et al. [26] found that identity development, particularly exploration, predicts greater civic engagement. Considering communalities (h2), the variables contributing the most collectively to the canonical correlation between the two sets of variables (positive transgender identity and gender identity development) were authenticity, social justice, and self-awareness of the PIM with all the U-MICS scales.

Table A1.

Canonical solution for gender identity development and positive transgender identity for Functions 1 and 2 (n = 117).

Table A1.

Canonical solution for gender identity development and positive transgender identity for Functions 1 and 2 (n = 117).

| Variable | Function 1 | Function 2 | h2 (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | rs | rs2 (%) | Coefficient | rs | rs2 (%) | ||

| Commitment | 0.79 | 0.93 | 85.89 | −0.05 | 0.05 | 0.29 | 86.18 |

| In-depth exploration | 0.21 | 0.08 | 0.63 | −0.94 | −0.99 | 97.19 | 92.82 |

| Reconsideration of commitment | −0.40 | −0.64 | 40.42 | −0.19 | −0.42 | 17.62 | 58.04 |

| Rc2 | 40.64 | 28.72 | |||||

| Self-awareness | 0.21 | 0.51 | 25.75 | −0.48 | −0.62 | 38.84 | 64.59 |

| Authenticity | 0.89 | 0.97 | 94.82 | 0.31 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 94.83 |

| Community | 0.03 | 0.27 | 7.23 | −0.32 | −0.54 | 28.68 | 35.91 |

| Intimacy | 0.06 | 0.40 | 15.72 | 0.08 | −0.17 | 2.75 | 18.47 |

| Social justice | −0.17 | −0.00 | 0.00 | −0.61 | −0.87 | 76.26 | 76.26 |

Note. Structure coefficients (rs) greater than |0.45| are underlined. Communality coefficients (h2) greater than 45% are underlined. Coefficient = standardized canonical function coefficient; rs = structure coefficient; rs2 = squared structure coefficient; h2 = communality coefficient.

Appendix A.1.2. Gender Identity Development (U-MICS) and Identity Functionality (FIS)

The multivariate canonical analysis of the U-MICS (three scales) and FIS (five scales) produced three functions, but only the first two functions were significant and substantial (squared canonical correlations of 0.39, 0.21, and 0.05; Function 1: Wilks’ Lambda = 0.45, F(15, 207.44) = 4.57, p < 0.001 and Function 2: Wilks’ lambda = 0.75, F(8, 152) = 2.96, p < 0.01). The overall model accounted for 54.56% of the variance in the relationship between the set of gender identity developmental dimensions and gender identity functions. Table A2 presents the coefficients associated with these analyses. Inspection of the structure coefficients for the first function suggests that structure and future orientation, followed by harmony, contributed the most to the FIS variable set in the correlation with the U-MICS scales, which were most influenced by commitment and reconsideration of commitment. That structure and future orientation of the FIS contributed to the function involving a relationship with commitment and reconsideration is not surprising, given that both structure and future orientation functions involve certainty, consistent with the confidence and security-tinged nature of the commitment identity process, while reconsideration of commitment reflects uncertainty (hence, different valence signs).

Table A2.

Canonical solution for gender identity development and identity functionality for Functions 1 and 2 (n = 83).

Table A2.

Canonical solution for gender identity development and identity functionality for Functions 1 and 2 (n = 83).

| Variable | Function 1 | Function 2 | h2 (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | rs | rs2 (%) | Coefficient | rs | rs2 (%) | ||

| Commitment | 0.64 | 0.87 | 76.34 | −0.17 | −0.06 | 0.36 | 76.70 |

| In-depth exploration | 0.12 | −0.09 | 0.87 | −0.98 | −0.99 | 97.55 | 98.42 |

| Reconsideration of commitment | −0.56 | −0.81 | 64.81 | −0.08 | −0.28 | 8.05 | 72.86 |

| Rc2 | 39.31 | 21.13 | |||||

| Structure | 0.84 | 0.92 | 84.65 | 0.48 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 84.65 |

| Harmony | −0.17 | 0.47 | 22.26 | 0.03 | −0.35 | 12.00 | 34.26 |

| Goals | 0.14 | 0.38 | 14.78 | −0.28 | −0.76 | 57.02 | 71.80 |

| Future | 0.48 | 0.78 | 60.29 | 0.03 | −0.43 | 18.36 | 78.65 |

| Control | −0.30 | 0.40 | 15.37 | −0.94 | −0.87 | 75.63 | 91.00 |

Note. Structure coefficients (rs) greater than |0.45| are underlined. Communality coefficients (h2) greater than 45% are underlined. Coefficient = standardized canonical function coefficient; rs = structure coefficient; rs2 = squared structure coefficient; h2 = communality coefficient.

For the second function, personal control, goal direction, and future orientation contributed the most to the FIS variable set, with only in-depth exploration contributing to the U-MICS variable set. The self-reflection involved in in-depth exploration likely prompts the self-motivational or willful functions of these three FIS components (i.e., goal direction, future orientation, and personal control). Indeed, Schwartz [101] found that the constructs of agentic personality (attributes reflecting self-direction in life) and eudaimonic self-discovery (searching for one’s true self in social environment) meaningfully contribute to developing carefully considered and self-validated (i.e., consolidated) identities. All variables were relevant to the overarching canonical correlation as evidenced by strong communalities (h2) (with the exception of the harmony scale of the FIS).

Appendix A.1.3. Gender Identity Functionality (FIS) and Positive Transgender Identity (PIM)

The canonical correlation between the PIM (five scales) and the FIS (five scales) produced five functions with only the first two being substantial and significant (squared canonical correlations of 0.42, 0.36, 0.13, 0.03, and 0.00; Function 1: Wilks’ Lambda = 0.32, F(25, 272.68) = 3.96, p < 0.001 and Function 2: Wilks’ lambda = 0.54, F(16, 226.71) = 3.15, p < 0.001). The set of FIS variables shared over two-thirds (68.32%) of the variance with the set of PIM variables. Inspection of coefficients in Table A3 reveals that the first function was influenced by FIS harmony, goals, and personal control, as well as positive transgender identity self-awareness and social justice. The second function was largely driven by the relationship of PIM authenticity and FIS structure, although all FIS variables influenced the gender identity functionality latent variable. Self-awareness and intimacy also contributed to the PIM variable set. The underlying meaning of FIS structure and PIM authenticity and self-awareness are congruent in that they reflect self-acceptance and self-consciousness (i.e., knowing oneself) in the individual. Overall, the communalities (h2) indicate that all dimensions of the FIS contributed substantially to the canonical correlation with positive transgender identity. Regarding the PIM, authenticity, self-awareness, and intimacy were the important scales contributing to the canonical correlation. Community and social justice may have had lesser roles, as these are more interpersonal rather than intrapersonal positive identity markers.

Table A3.

Canonical solution for gender identity functionality and positive transgender identity for Functions 1 and 2 (n = 83).

Table A3.

Canonical solution for gender identity functionality and positive transgender identity for Functions 1 and 2 (n = 83).