1. Introduction

Same-gender and transgender parents are targets of negative attitudes concerning parental competence, with a potential negative impact on these families’ well-being and rights [

1,

2,

3,

4]. However, there is a lack of studies that have investigated attitudes toward asexual parents.

People who identify as asexual, or belonging to the ace spectrum, are those who have absent/reduced sexual attraction to any gender or whose sexual attraction depends on specific circumstances (e.g., demisexual people [

5]). According to some authors [

6,

7], asexuality can be conceptualized as a continuum from minor to no sexual attraction [

5,

7]. Furthermore, a multidimensional approach to asexuality was investigated, considering the complex relationships among identity, attraction, behavior, and desires to capture the heterogeneity of this population [

8,

9]. Over the past two decades, definitions of asexuality have become more clearly articulated and models that pathologize this sexual orientation have been increasingly abandoned [

10,

11]. Asexuality is now recognized as one of the normal variations in sexual orientation that is not inherently linked to individuals’ sexual behaviors or choices [

10]. The defining element of asexuality is sexual attraction [

12,

13]. However, studies also suggest a potential correlation of lack of sexual attraction and aspects of sexual desire and sexual behavior, showing, for instance, that asexual individuals tend to report lower levels of sexual fantasies, masturbation, and number of sexual partners compared to allosexual individuals. Allosexual people are people who do experience sexual attraction or an intrinsic desire to have sexual relationships. These people are also referred to as “sexual”, as cited both by activists (The Asexual Visibility and Education Network,

https://www.asexuality.org/?q=general.html, accessed on 15 June 2024) and in the scientific literature [

12,

13]. Recent studies have also reported that a significant number of asexual people can engage in sexual intercourse and can have a variety of physically intimate behaviors, including kissing, cuddling, manual, oral, anal, and vaginal sex, in addition to playing with toys [

5].

Asexuality is about the lack of sexual attraction, not the inability to experience intimacy, empathy, and relational or parental desire. It is possible and “normal” for asexual individuals to be aromantic and childfree. However, according to Weis et al. [

14], nearly 80% of asexual individuals desire some form of relationship, and some have children. Furthermore, nearly 50% of asexual people desire children primarily through adoption. However, since sexual activity is necessarily and erroneously tied to sexual attraction that, in turn, is considered universal and inevitable [

15], asexual people could have their sexual identity invalidated, especially when they have children.

Furthermore, we live in a context of compulsory sexuality [

16], which—much like heteronormativity—establishes a normative and “natural” framework for sexual behavior and the acceptable ways in which it should occur within specific social and moral expectations. However, asexual individuals challenge this norm, not merely because many of them have reduced sexual behaviors (a behavior that can result from many reasons unrelated to identity, such as celibacy), but because they do not experience sexual attraction. This situates their choices on a different level compared to people of other sexual orientations (i.e., allosexual people), and instead connects them to alternative forms of intimacy and attraction. Like other forms of sexual prejudice, prejudices against asexual individuals can vary in intensity, ranging from subtle forms of allonormative biases to extreme violence (e.g., social exclusion, bullying, and corrective rape [

17]). They are associated with traditional gender roles, social dominance orientation, and moral disengagement, and can occur even within the LGBTQIA+ community [

18]. Prejudice against asexuality often leads perpetrators to attempt to “correct” asexual individuals through sexual violence. For example, from a global sample of 8752 individuals on the asexual spectrum, Chan et al. [

19] found that 67.4% of the participants had experienced at least one form of sexual violence, with the most common forms of victimization being sexual assault (e.g., the act of sexual touching without the person’s consent) and sexual harassment (e.g., unwelcome sexual advances). According to MacInnis et al. [

20], anti-asexual attitudes were associated with higher levels of religious fundamentalism. This is likely because asexuality challenges traditional beliefs about sexuality, gender roles, and relationship values that religiosity strongly defends to preserve the status quo. In extreme cases, this denial of asexuality as a valid identity can lead to justifying sexual coercion. This may be especially true for asexual women: identifying as asexual is an agentic act requiring self-knowledge, yet this kind of sexual agency contradicts dominant norms of womanhood, which expect women to be passive, compliant, and tolerant of epistemic injustice [

21]. Furthermore, when an asexual woman chooses to become a mother, she further challenges the assumption that a woman passively accepts a man’s sexual act, because she seems to reclaim even reproductive agency. Therefore, asexual mothers can also face prejudice, stereotypes, and overt discrimination.

Research investigating attitudes and prejudice toward asexual people is increasing [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. However, research on attitudes toward asexual people who are in relationships and have children has been much more limited. This study aimed to compare social attitudes toward mothers who are asexual and allosexual.

1.1. Stereotypes Toward Asexual People and Asexual Parenting

Attitudes toward asexual individuals and asexual parents remain underexplored, and public awareness of asexuality is still relatively low. This invisibility does not shield asexual people from negative attitudes, which can have a significant detrimental impact on their lives. In qualitative interviews with 12 US asexual college students, Mollet [

25] found that the invisibility of asexuality and the omnipresence of allonormativity were themes identified across all the data, impacting students’ identity management and disclosure. Furthermore, biases conflating asexuality with chastity tended to invalidate asexual people’s life experiences and identities.

Studies found that anti-asexual biases and biases against gay men and lesbian women could be associated [

22]. Also, according to MacInnis et al. [

20], prejudice toward asexual people is a type of sexual prejudice. Therefore, according to a general negativity account [

20], some elements of commonalities with biases toward gay men or lesbian women were expected. However, recent studies relied on the stereotype deduction account [

15], which found certain specificities of stereotypes toward asexual people. Zivony et al. [

15] showed that biases toward asexual people have to do with an assumption (often implicit) that low levels of sexual attraction are a pathological aspect of mental health or just a “phase” of immaturity in which asexual people have not met someone to whom they are sexually attracted [

9,

27]. This incorrect assumption stems from general allonormative assumptions of sexuality and sexual attraction that are conceptualized as inevitable and universal. Zivony et al. [

15], indeed, found that asexual people tend to be stereotyped as more immature, introverted, or using their identity to excuse social avoidance compared to heterosexual people. However, in this research, asexual people were evaluated as more conscientious (a trait often associated with competence) than heterosexual people. In this study, LGB targets were not present. Thus, it remains unclear how these stereotypes differ from those directed at LGB individuals, and how they may influence perceptions of parenting behaviors. What happens when sexual prejudice intersects with stereotypes about parental competence and warmth?

According to the Stereotype Content Model (SCM; [

28]), social perception is organized into two fundamental and universal dimensions, warmth and competence, that underline and differentiate group stereotypes. These dimensions aligned with the social roles men and women have held in society. The SCM and, more broadly, the attribution of warmth and competence to sexual and gender minorities have been explored without reaching definitive conclusions. Recent studies [

29] show that gay, lesbian, and bisexual groups are perceived as being more similar to their non-congruent gender category than heterosexual people of the same gender. Implicit associations link “women” more strongly with “warmth” than “men,” but no other significant links between warmth/competence and gender or sexual orientation were found. According to some studies, asexual men could represent a violation of masculinity norms of men wanting sex with multiple partners [

30], and asexual women could represent a violation when they do not have expected sex with their romantic partner. Indeed, sex is stereotyped as a fundamental aspect of sociality, especially for men, and talking about one’s own sexual behaviors is often seen as a strategy for asserting masculinity in front of other men [

31,

32]. In this sense, asexual identity itself can present a form of threat to masculinity. This also aligns with the theory of precarious manhood [

33], which posits that masculinity is a social status that must be continually earned and is easily threatened. Asexuality defies these gendered expectations of male sexual attraction as innate and demonstrates that masculinity can exist independently of sexual attraction and performance [

5]. Similarly, women who completely reject sexual attraction in relationships may be perceived as deviant, pathological, or emotionally cold. Extending this reasoning to parenthood, asexual individuals may also be seen as violating traditional expectations that link sexual activity to reproductive roles for both men and women. Moreover, given that the existing literature has already shown that “non-traditional” parents are often subject to stereotyping [

34], the SCM can help explain how asexual parents—precisely because they are viewed as counter-stereotypical—may be vulnerable to discrimination. Stereotypes associated with motherhood and fatherhood could vary in terms of competence and warmth depending on whether parents are fulfilling traditional gender roles or not. For instance, Sheeran et al. [

35] explored stereotypes associated with teenage parents among Australian community members. The authors found that teenage parents were seen as less warm, competent, and moral than adult parents. If teenage parents are often perceived as immature, it is possible that asexual parents may likewise be stereotyped as less competent and warm compared to other allosexual adult parents. In an experimental study, Di Battista et al. [

36] found that lesbian and heterosexual stepmothers were perceived as being less competent parents, with fewer positive traits, and more responsible for a child’s misbehavior as compared to heterosexual biological mothers. However, the biases associated with asexual parents as well as perceptions about their warmth were not investigated.

1.2. Dehumanization of Asexuality

Stereotypes are associated with dehumanization processes [

37]. For instance, qualitative studies showed that asexual people tend to be discriminated against and dehumanized through rhetorical stereotypes of aliens, robots, and monsters [

38]. Analyzing qualitative data of discourse from anonymous posts on AVEN and Reddit—platforms—the authors explored how rhetorics of allonormativity operate through stereotypical images. These stereotypes were found to be common descriptors used to discriminate, invalidate, and otherize asexual individuals. Some of this violence originated from allosexual queer individuals who contributed to the exclusion of asexual people even from the queer communities.

According to the dual model of dehumanization [

39], individuals can deny humanity to others and to outgroups in two distinct ways: (1) by denying traits associated with uniquely human characteristics (UH), such as higher-order cognition, rational planning, and self-control; and (2) by denying traits related to basic human nature (HN), such as the capacity to feel fear, hunger, desire, or pleasure. The first type of dehumanization leads to perceiving the target as animalistic and lacking in self-control, whereas the second results in perceiving the target as cold and mechanical. In other words, according to studies on dehumanization processes [

39], the denial of HN is considered a form of “mechanistic dehumanization”, in which the target is perceived as being cold, rigid, and passive. On the contrary, denying UH is considered a form of “animalistic dehumanization” (e.g., the target is perceived as uncultured and irrational [

39]).

MacInnis et al. [

20] argued that the processes of dehumanization based on the denial of HN could be associated with the discrimination of asexual targets. Indeed, “mechanistic dehumanization” is related to the denial of traits that describe the capacity to feel desire and pleasure, resulting in perceiving the target as cold and mechanical. In this sense, in the denial of HN, the human being is compared to a robot ([

39], p. 258). Also, Hoffarth et al. Hoffarth et al. [

40] argued that asexual people are probably not perceived as “morally repugnant” (p. 3), but could be devalued and invalidated consistent with dehumanization processes, particularly for HN traits. In 2012, MacInnis and Hodson investigated attitudes toward asexual people in two studies among university students and community samples in Canada and the US. The authors argued that there is a “strong overlap between sexuality and ‘humanness’” (p. 729). Indeed, the results confirmed an association between asexuality and dehumanization. Participants were asked to evaluate heterosexuals, homosexuals, bisexuals, sapiosexuals, and asexual target groups in terms of trait-based dehumanization measures. Dehumanization was represented by heterosexual participants’ denial of HN traits—such as being friendly, helpful, and loving—and the denial of emotional capacities, including optimism, desire, happiness, and affection to asexual targets. However, asexual people were also discriminated against by heterosexual people on measures of imagined future contact, and discomfort in willingness to rent to or hire them. On the contrary, lesbian women and gay men were perceived as being exceptionally high in human nature traits and emotionality [

20]. It is important to note that the study was correlational in nature and did not consider the gender of the targets or their parental role. In a vignette study involving a sample of US college students, Bittle et al. [

22] used the same dehumanization measures used by MacInnis et al. [

20] to explore attitudes toward asexual people. The results of their study did not support previous findings on dehumanization. However, the authors combined human nature and uniquely human traits into a single factor, obscuring the possibility of investigating the effects separately.

In general, dehumanization processes could be associated with negative attitudes and discrimination. Opotow [

41] argued that “denying a person a fully human mind legitimizes harm by placing her outside the boundary in which moral values, rules, and considerations of fairness apply” (p. 1). Denying humanity to an outgroup can have significant negative consequences, such as increasing the perceived culpability of the target [

42] and reducing the likelihood of attributing praise [

43]. In a vignette study, Monroe et al. [

44] found that people were likely to view members of a sexual outgroup (e.g., a gay man or a person with AIDS) as lacking a rational mind (UH). Moreover, this dehumanization process predicted lower positive attitudes toward these targets (measured as a combined score of perception of warmth, alliance, and other items). Studies investigating the dehumanization processes of LGBTQIA+ parents are rare. In an experimental vignette study [

45], Italian participants evaluated three typologies of mothers (a heterosexual biological mother, a heterosexual stepmother, or a lesbian stepmother) on competence stereotypes and dehumanization traits (human and animal traits). The results showed that the depicted heterosexual biological mother was perceived as being more competent compared to the other targets. However, animal traits were attributed more to the depicted heterosexual stepmother than the others. Moderated mediation analyses also showed that participants endorsing moderate and high levels of traditional gender role beliefs rated the heterosexual stepmother as being less competent compared with the heterosexual biological mother by animalizing her. An asexual mother target was not investigated.

Building on Monroe and Plant’s [

44] findings, and considering the limited literature on dehumanization processes applied to LGBTQIA+ parents [

45], in this study, it was predicted that an asexual mother may be dehumanized in terms of lacking human nature traits (e.g., emotional depth), rather than mind-based attributes. Indeed, the absence of sexual attraction is expected to conflict with essentialist expectations surrounding maternal instincts and emotional warmth. This specific form of dehumanization could help explain why people might be more likely to blame an asexual mother for cold or emotionally distant parenting behavior, not due to perceived irrationality but rather due to assumptions about emotional deficiencies.

Specifically, drawing on the dual model of dehumanization, this experimental study aimed to investigate the denial of traits associated with human nature (HN; denial of basic human emotions) and human uniqueness (HU; denial of a rational mind), as well as perceptions of parenting competence and warmth attributed to different maternal targets. It was hypothesized that asexual mothers would be judged more negatively on the HN dimension (i.e., denial of basic human emotions), but not on the HU dimension (i.e., denial of a rational mind), compared to allosexual mothers, both heterosexual and lesbian (H1). This study also tested whether dehumanization mechanisms are associated with warmth attributions for mothers’ behaviors on the basis of their sexual orientation. In particular, it was predicted that perceived negative behavior toward children for asexual mothers compared to heterosexual mothers, assessed in terms of lower warmth, would be associated with the denial of HN (but not HU) (H2). Potential confounds (i.e., participants’ gender, age, sexual orientation, and parenting status) were investigated. These factors are known to influence attitudes toward sexuality and gender roles [

1]. Controlling for them allows us to isolate the specific effects of the experimental manipulations and reduce bias in the interpretation of the results.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

Power analysis using G*Power 3.1, testing for Ancova, and assuming a medium effect size (f = 0.025) for a power of 0.80 revealed a required sample size of 269. Participants were N = 298 people living in Italy (224 women; 75.2%; 1 nonbinary person; 0.3%; M age = 35.97, SD = 15.04, from 18 to 78; two missing values). No participant was self-defined as a transgender person. As for sexual orientation, most participants self-defined as heterosexual (285; 95.6%), ten of them were bisexual or pansexual (3.4%), and one was a gay man (two were missing values). Almost half of the participants self-defined as parents (140; 47%), and 156 were childfree participants (52.3%; 2 missing values).

According to place of residence, 193 people were from Northern Italy (64.8%), and 103 from Central and Southern Italy (34.5%, 2 missing values). As for occupation, 209 participants were workers (70.1%), 58 students (19.5%), 11 were in search of an occupation (3.7%), and 19 were in other conditions (e.g., retired; 1 missing value). The level of education was medium–high, with 172 participants having a high-school-level certificate (57.7%), and 106 with a degree certification (37.6%; the remaining participants possessed lower educational attainment). Potential participants were recruited using a convenience sample strategy, were notified that the study was completely anonymous, and could skip any question(s) they did not wish to answer. Then, they gave their consent to participate. After filling out the sociodemographic section, each participant was randomly assigned to one of three vignettes, which prevented any survey ordering effects.

The research complied with the WMA Declaration of Helsinki (1964/2013). Ethical approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of G. Marconi University (approval number: 12072024) on 12 July 2024.

2.2. Materials and Measures

The Vignettes. Participants read one of three different vignettes (see the

Supplementary Materials). After an introduction explaining what sexual orientation is (following the same procedure as [

20]), the vignette scenario was introduced. The scenario clearly specified that the children were living with their biological parents. It was then stated that this mother was heterosexual [lesbian or asexual]. The mother argued with her children, who wanted to buy some sweets. Indeed, the vignette presented a typical disagreement that could occur between parents and young children. The vignettes were identical except for the mother’s sexual orientation, which was manipulated: (1) a heterosexual mother (

n = 98); (2) a lesbian mother (

n = 99); and (3) an asexual mother (

n = 101). Each participant read one version of the vignettes, and then they responded to three manipulation and attention-checking items (“

Anna is the biological mother of Antonio and Sara”; “Anna is asexual [lesbian/heterosexual]”; and “

Antonio and Sara are misbehaving”. Responses: 1 =

true or 2 =

false).

Denial of a Rational Mind: Participants rated two items [

44] for the measure of the denial of a rational mind (

rho = 0.43;

M = 3.25,

SD = 1.12; and skewness = 0.29, kurtosis = −0.48) from 1 = “

not at all” to 6 = “

very much” (e.g., “

Anna showed to be rational and logical—reversed item [lacking self-control]”).

Denial of Basic Human Emotions: Participants rated two items [

44] for the measure of the denial of basic human emotions (

rho = 0.50;

M = 3.46,

SD = 1.06; and skewness = −0.11, kurtosis = −0.36). These items were rated from 1 = “

not at all” to 6 = “

very much” (e.g., “

Anna showed to be rigid and insensitive [affectionate toward her children—reversed item]”).

Competence and Warmth. Bipolar adjectives measuring stereotypical parenting traits concerning the depicted mother’s behavior (adapted from [

46]) were assessed at opposite poles of a 6-point scale. As for competence, the items were incompetent/competent, unprepared/prepared, and incapable/capable; as for warmth, the items were cold/warm, hostile/loving, and neglectful/nurturing. A total score for each of the dimensions was computed on the grounds of the mean (competence:

α = 0.95, 95% confidence interval: BootLLCI = 0.93, BootULCI = 0.96;

M = 3.81,

SD = 1.28; skewness = −0.13, kurtosis = −0.59; warmth:

α = 0.88, 95% confidence interval: BootLLCI = 0.84, BootULCI = 0.90;

M = 3.25,

SD = 1.15; skewness = 0.24, kurtosis = −0.19). A CFA was run to observe the data’s reliability and validity by examining how well the measured variables represented the latent variables. The model, with three indicators for competence, and three indicators for warmth, provided an almost perfect fit to the data: χ8(298) = 4.38,

p = 0.82; RMSEA = 0.000 (90% CI: 0.000, 0.042); CFI = 1; TLI = 1; SRMR = 0.019.

2.3. Data Analyses

Analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25.0. Descriptive analyses, reliability, and correlation analyses can be seen in

Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials. Indices of skewness and kurtosis were adequate to prove the normal distribution of the data because no dimension exceeded |1|. A Confirmatory Factor Analysis—CFA—was conducted for the competence and warmth dimensions. Item loadings into each dimension, the consistency of the items of each subscale, and the impact of removing or maintaining each item on the subscale consistency were inspected.

Furthermore, a one-way Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) was conducted on the denial of rationality and basic human emotions, controlling for several covariates (i.e., age, gender, sexual orientation, and parental status). In addition, a repeated-measures Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) was carried out, with competence and warmth as within-subject dependent variables, and scenario (defined by the sexual orientation of the target: heterosexual, lesbian, or asexual) as the between-subjects factor.

Then, two parallel mediation models using Hayes’s [

47] PROCESS macro (Model 4) with 10,000 bootstrapped samples were performed to test the mediation role of the denial of a rational mind and the denial of human emotions in perceptions of competence and warmth. They were selected as the “indicators” for a three-group design, and two comparisons were generated: the control group (heterosexual mothers) vs. lesbian mothers (X1), and the control group vs. asexual mothers (X2).

3. Results

Denial of a Rational Mind: The ANCOVA indicated no significant effects for covariates. The Levene test indicated that the groups were homogeneous, F (2, 291) = 1.09, p = 0.33; therefore, the assumptions for the ANCOVA were met. A significant main effect of sexual orientation emerged, F(2, 287) = 7.53, p = 0.001, partial η2 = 0.05. The effect of the depicted mothers’ sexual orientation on the denial of a rational mind was significant. Participants consistently denied a rational mind to the asexual mother (M = 3.62, SD = 1.13), more than to the heterosexual mother (M = 3.15, SD = 1.13, p = 0.005), but also compared to the lesbian mother (M = 2.97, SD = 0.99, p = 0.001). No other differences were statistically significant.

Denial of Basic Human Emotions: The ANCOVA indicated no significant effects for covariates. The Levene test indicated that the groups were homogeneous, F(2, 291) = 1.09, p = 0.34, and therefore the assumptions for the ANCOVA were met. A significant main effect of sexual orientation emerged, F(2, 287) = 18.7, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.11. The effect of the depicted mothers’ sexual orientation on the denial of human emotions was significant. Participants consistently denied human emotions to the asexual mother (M = 4.02, SD = 0.95), more than to the heterosexual mother (M = 3.11, SD = 1.02, p = 0.005) and the lesbian mother (M = 3.24, SD = 0.99, p = 0.001). No other effects were significant.

Competence and Warmth: A MANOVA was performed to analyze the different levels of competence and warmth evaluations depending on the types of mothers. Box’s M test was significant. Therefore, a Pillai trace criterion was used. The results revealed a significant multivariate omnibus for competence and warmth, Pillai’s trace = 0.16, F (1, 295) = 54.74, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.16, as well as the factor X scenario interaction, Pillai’s trace = 0.03, F (2, 295) = 5.07, p = 0.01, partial η2 = 0.03. The evaluations of competence (M = 3.82, SD = 1.28) were generally higher compared to the evaluation of warmth (M = 3.27, SD = 1.15). The univariate results showed that, for competence, the depicted lesbian mother was judged as less competent (M = 4.01, SD = 1.24) compared to the depicted heterosexual mother (M = 4.35, SD = 1.09), but more competent compared to the depicted asexual mother (M = 3.08, SD = 1.16, F (2, 295) = 31.67, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.18). The depicted asexual mother was judged to be less competent than the depicted heterosexual mother (p < 0.001). The depicted lesbian mother was judged to be equally warm (M = 3.58, SD = 1.11) as the depicted heterosexual mother (M = 3.48, SD = 1.25), but warmer compared to the depicted asexual mother (M = 2.75, SD = 0.90, F (2, 295) = 16.84, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.10). The depicted asexual mother was judged to be less warm than the depicted heterosexual mother (p < 0.001). Moreover, all of the target mothers were judged as being more competent than warm (heterosexual: F (1, 295) = 46.08, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.13; lesbian: F (1, 295) = 11.49, p = 0.001, partial η2 = 0.04; and asexual: F (1, 295) = 6.80, p = 0.01, partial η2 = 0.02).

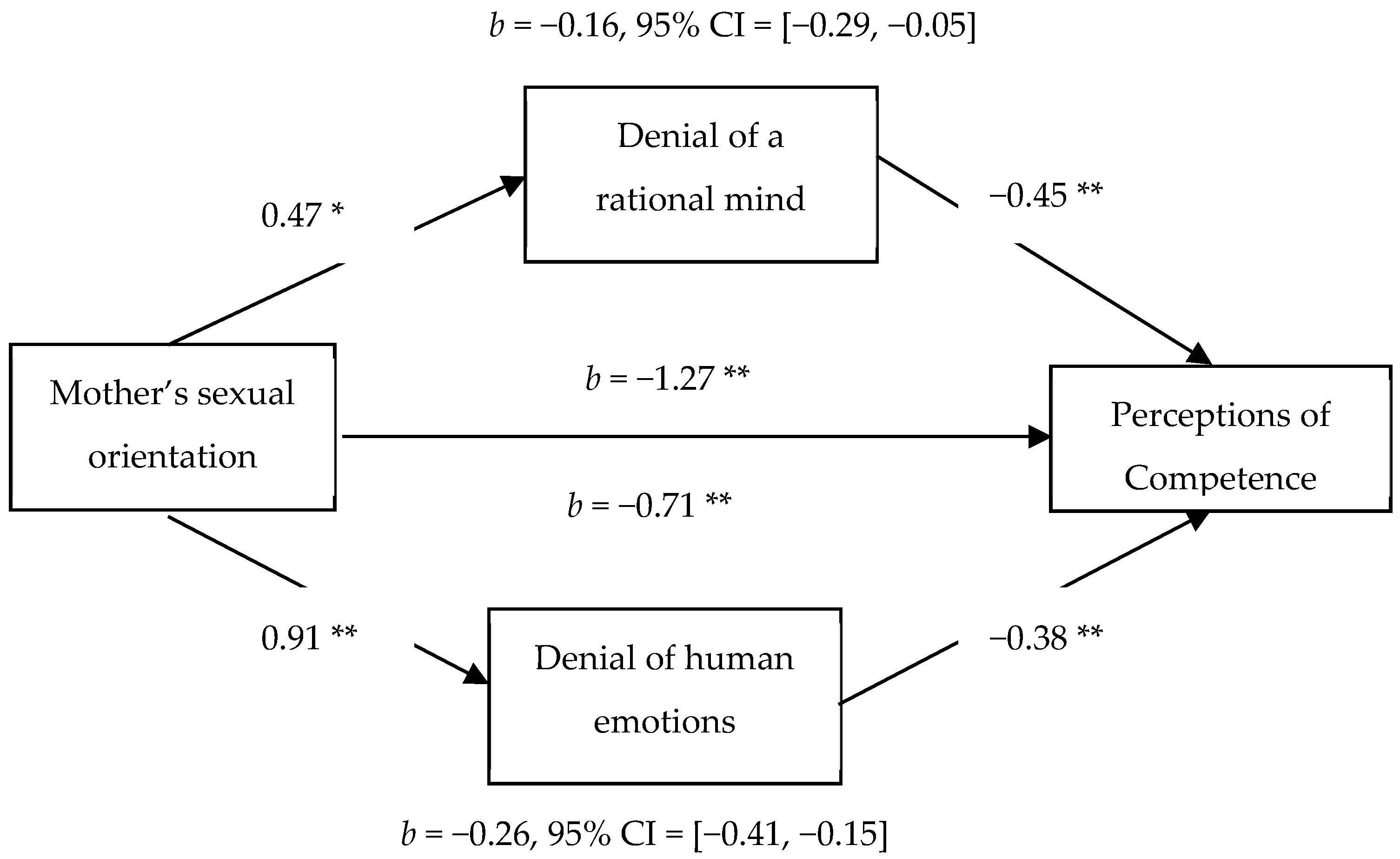

Parallel Mediation for Competence: The results of the first parallel mediation revealed significant indirect effects of the type of mother on attributions of competence through both the denial of a rational mind and the denial of human emotions, but only for the asexual target compared to the heterosexual one (see

Figure 1). The denial of a rational mind was negatively associated with competence attributions,

b = −0.45, SE = 0.05,

t = −8.33,

p < 0.001. Additionally, the denial of human emotions was negatively associated with competence attributions,

b = −0.38, SE = 0.06,

t = −6.37,

p < 0.001. Critically, there was a significant indirect effect of manipulation of the mother’s sexual orientation (only for the asexual target vs. the heterosexual target) on perceived competence through both the denial of a rational mind,

b = −0.16, BootSE = 0.06, 95% confidence interval (CI) = [−0.29, −0.05], and the denial of human emotions,

b = −0.26, BootSE = 0.06, 95% confidence interval (CI) = [−0.41, −0.15], Δ

R2 = 0.05,

F(2, 293) = 13.14,

p = 0.001.

No differences were found for the comparison between lesbian and heterosexual targets.

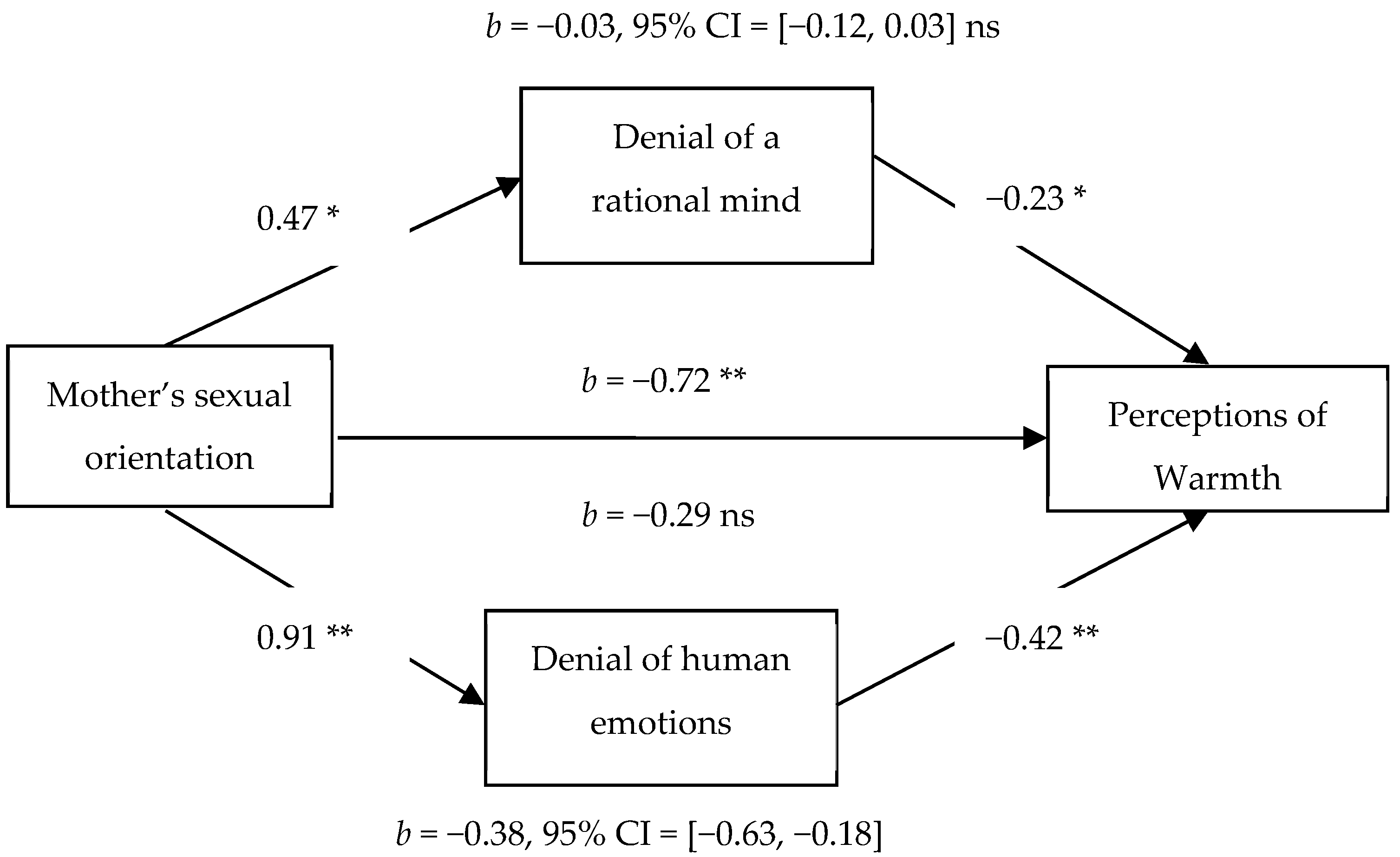

Parallel Mediation for Warmth: In line with

H2, the results of the second parallel mediation revealed significant indirect effects of the type of mother on attributions of warmth through the denial of human emotions only for the asexual target vs. the heterosexual target (see

Figure 2). The denial of a rational mind was negatively associated with warmth attributions,

b = −0.23, SE = 0.09,

t = −2.31,

p = 0.02. Additionally, the denial of human emotions was negatively associated with warmth attributions,

b = −0.42, SE = 0.11,

t = −3.84,

p < 0.001. Critically, there was not a significant indirect effect of the manipulation of the mother’s sexual orientation on perceived warmth through the denial of a rational mind,

b = −0.03, BootSE = 0.04, 95% confidence interval (CI) = [−0.12, 0.03]. However, there was an indirect effect of the manipulation of the mother’s sexual orientation on perceived warmth through the denial of human emotions for the asexual target vs. the heterosexual target,

b = −0.38, BootSE = 0.11, 95% confidence interval (CI) = [−0.63, −0.18], Δ

R2 = 0.10,

F(2, 295) = 16.84,

p = 0.001.

No differences were found for the comparison between lesbian and heterosexual targets.

4. Discussion

Based on the previous findings of MacInnis et al. [

20], Di Battista [

45], and Bittle et al. [

22], this experimental study investigated anti-asexual biases directed at asexual mothers, exploring both processes of dehumanization and stereotyping. In line with the predictions, the denial of human emotions (HN) was significantly higher for an asexual mother target than the other two target mothers (lesbian and heterosexual). These findings confirmed previous study results showing that mechanistic dehumanization is stronger for asexual targets compared to other sexual minority targets [

20]. However, surprisingly, the results found that the denial of a rational mind (HU) was higher, as well as attributions of competence being lower, for the asexual mother target compared to the other two targets. Moreover, the asexual mother was perceived as less competent compared to the heterosexual mother via the partial mediation of the denial of both HU and HN. In line with the prediction, the asexual mother’s behavior was also perceived as less warm compared to that of the heterosexual mother via the full mediation of the denial of HN. These findings showed that asexual mothers (relative to heterosexual mothers) were dehumanized on both dimensions of animalistic and machine-like dehumanization. In general, asexual mothers were perceived more negatively than both heterosexual mothers and lesbian mothers on all the dimensions explored in this study because they were denied mind and emotions, and the behavior was stereotyped as being incompetent and cold. No sociodemographic variables affected these relationships.

Of the large number of studies that have measured the perceived competence of sexual minority parents [

48], few studies have investigated perceptions of warmth (e.g., [

35,

49]). However, parental warmth is significantly associated with children’s psychological adjustment and personality dispositions, including independence, self-esteem, self-adequacy, emotional responsiveness, and stability [

50]. Therefore, perceiving that parents are deficient in both parental competence and warmth solely based on their sexual orientation can have a negative impact on attitudes toward these parents. Anti-asexual biases could also have an impact on asexual people’s lives, impacting isolation, unwanted sex, and relationship conflict [

16]. Women and mothers who identify as asexual develop a heightened awareness of themselves and of the complexities of attraction and intimacy—an act of epistemic agency in itself [

21]. However, dominant gender norms, which portray women as passive in their sexual agency and mothers as equally passive in their reproductive choices, can lead to the invalidation of their identity (e.g., “You just haven’t found the right partner”), the dismissal of their epistemic voice (e.g., “You don’t really know what you want”), pressures to “fix” or medicalize asexuality, and even the denial of consent through harmful assumptions such as “All women want it eventually, even if they say no.” Additionally, asexual mothers who choose to become mothers may, therefore, be targets of sexual prejudice, like other LGBTQIA+ parents.

This study highlights certain differences in the level and type of stereotypes and discrimination faced by asexual individuals—or at least by those who occupy highly gendered roles shaped by cis-heteronormative and allonormative expectations, such as motherhood. The idea that a mother can fulfill her role well without experiencing sexual attraction should be considered unremarkable; however, the absence of sexual attraction still appears to be a significant source of pathologization and discrimination. In fact, asexuality continues to be targeted by conversion practices at higher rates than other sexual orientations (National LBGT Survey, 2018,

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-lgbt-survey-summary-report (accessed on 1 July 2025)). Asexual communities have challenged heteronormative ideas of relationships through alternative models of intimacy, partnerships, and parenting that resist compulsory sexuality, allonormativity, and normative ideas of families. Importantly, engaging in intimate relationships and parenting does not invalidate asexual identity, as asexuality concerns patterns of sexual attraction—not necessarily the absence of physical and sexual connection. Research has also shown that the compulsory nature of sex and romance tends to be unevenly imposed across ability, race, gender, age, and national context. Future research should therefore more explicitly examine the intersection between asexuality, gender, and race, to better understand how individuals navigate, resist, or are marginalized by dominant sexual and romantic norms [

51]. In this study, parental competence tends to be more important than parental warmth, as it involves providing appropriate care and support to children. Within the framework of the SCM, this might appear counterintuitive at first glance—but, in this study, we are comparing only mother targets who differ in sexual orientation. A comparison with fathers or with other female targets (e.g., non-mothers or working women) might reveal different patterns of results.

This study has several limitations to consider: First, women were prevalent. Future research should consider a more gender-balanced sample, as well as measure participants’ gender role stereotypes and sexual prejudices. In addition, although the prediction of the influence of dehumanization processes on warmth and competence stereotypes was based on theoretical assumptions [

35,

44], this relationship could also be reversed. Future studies could manipulate some of these dimensions to test the causal effects of these relationships. Furthermore, in this study, the labels “asexual”, “heterosexual”, and “lesbian” do not necessarily imply that some nuances cannot exist, nor exclude overlap with other sexual or romantic identities. This is particularly relevant given that sexual attraction may not align with romantic (or other forms of) attraction [

32]. Future studies should consider the possibility of individuals belonging to multiple sexual identities. Asexual people generally do not experience sexual attraction, as implied in the scenario of this study, but in some rare cases they might—such as those who identify as graysexual. Moreover, asexual individuals may experience other types of attraction, such as romantic, emotional, platonic, or others (in which case they might identify as panromantic asexuals, among many other possibilities). Allosexual individuals may also identify with multiple labels in the same way. Additionally, each dimension of sexuality (e.g., sexual behavior, arousal) can vary in intensity and may be directed toward no, one, or more genders.

As for implications and in line with MacInnis et al. [

20] and Bogaert [

52], presenting evidence of prejudice regarding asexual people (or people from the ace spectrum) allows them to emerge from the invisibility and denial of identity to which they are often subjected. Understanding the motivations underlying prejudice directed at marginalized groups, such as same-gender parents, also seems vital for developing appropriate strategies to contrast prejudice. Furthermore, a social understanding of asexuality could help allosexual people to better understand the complex relationships among identity, sexual attraction, behavior, and desires [

9]. In addition, asexual parents, as well as LGBTQIA+ parents, can also contribute to the challenge of having—and parenting—children being perceived as necessarily tied to sexual relationships.