Mapping Evidence on Strategies Used That Encourage Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Uptake and Adherence Amongst Female Sex Workers in South Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Question

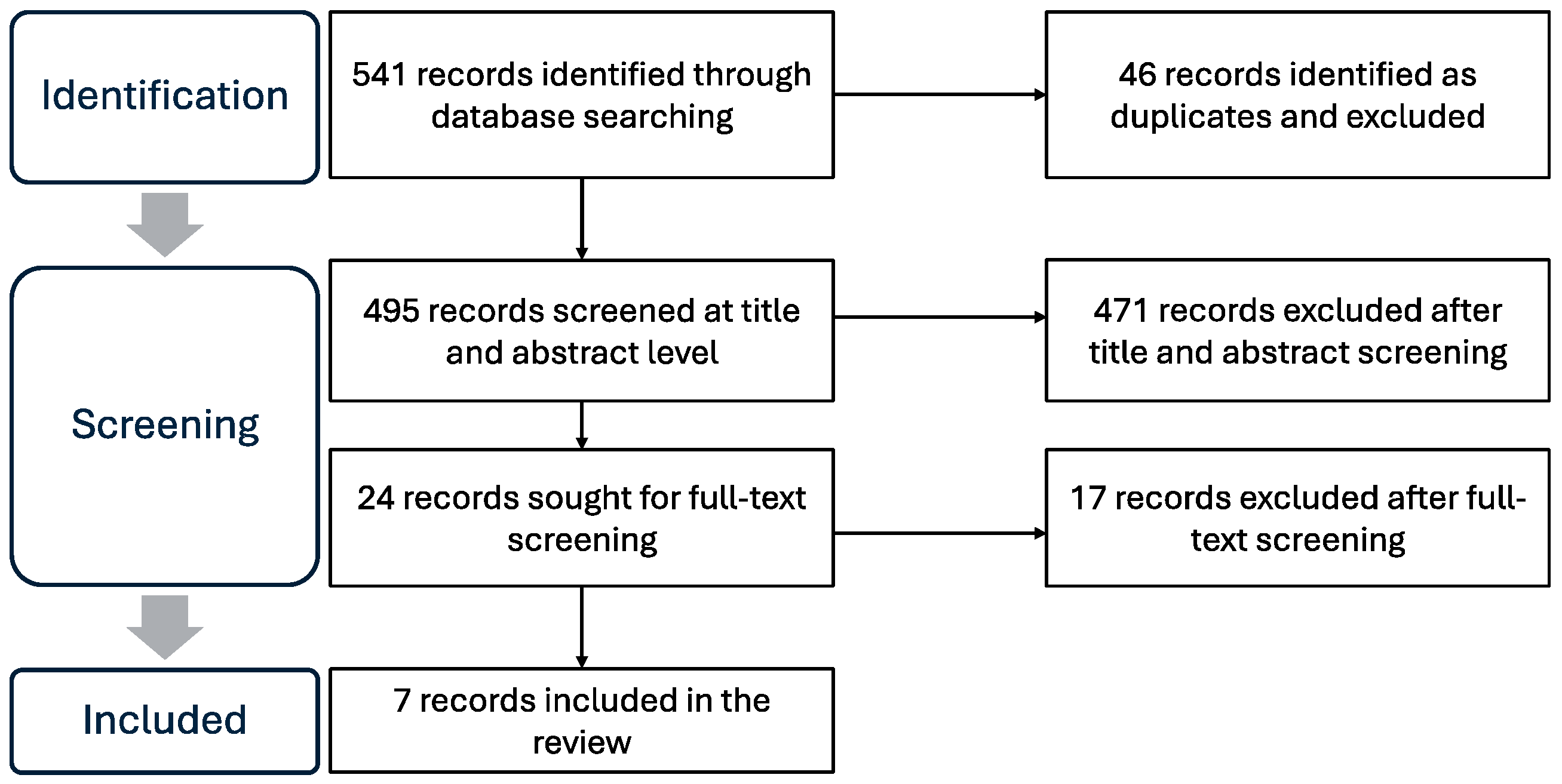

2.2. Identifying Relevant Studies

2.3. Selecting Relevant Studies

2.4. Charting the Data

2.5. Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

| Author | Publication Title | Aim/s and Methods | Context | Participants | Summary of Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Makhakhe et al. (2022) [32] | “Whatever is in the ARVs, is Also in the PrEP” Challenges Associated with Oral Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Use Among Female Sex Workers in South Africa | The purpose of this study was to explore barriers to the uptake of PrEP among FSWs Qualitative study | Urban city of Durban | 11 peer educators, one site coordinator, and one counsellor (thus, a total of 13), while the rest were FSWs (18) |

|

| Chimbindi et al. (2022) [33] | Antiretroviral therapy-based HIV prevention targeting young women who sell sex: A mixed method approach to understand the implementation of PrEP in a rural area of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa | To describe PrEP access, awareness and uptake for AGYW, and community norms around PrEP Mixed methods (qualitative and quantitative) | Rural area of KwaZulu-Natal | Key informants (n = 33), community members (n = 19), 10–35-year-olds (n = 58) and stakeholder/providers (n = 9) |

|

| Pillay et al. (2020) [34] | Factors influencing uptake, continuation, and discontinuation of oral PrEP among clients at sex worker and MSM facilities in South Africa | The goal of this study was to identify barriers and facilitators to oral PrEP uptake, retention, and adherence in South Africa Mixed methods (cross-sectional observational) | Rural, per-urban and urban areas in Limpopo, Gauteng, KwaZulu-Natal and Western Cape | 299 clients (203 from sex worker facilities, 96 from MSM facilities) |

|

| Mateboge et al. (2023) [35] | Planning for decentralized, simplified prEP: Learnings from potential end users in Ga-Rankuwa, Gauteng, South Africa | To paper presents young and older people’s preferences for decentralized, simplified PrEP service delivery and new long-acting HIV prevention methods, in Ga-Rankuwa, South Africa Qualitative study | Peri-urban area in Ga-Rankuwa, Tshwane district, Gauteng Province | 109 participants (36 AGYW, 46 ABYM, 10 Female sex workers, 4 Pregnant AGYW, 8 MSM and 5 Unspecified) |

|

| Rao et al. (2023) [36] | The impact of implementation strategies on PrEP persistence among female sex workers in South Africa: an interrupted time-series study | To estimate level changes in 1-month oral PrEP persistence associated with rollout of various implementation strategies among FSWs across nine districts in South Africa Interrupted time series (ITS) design | 9 districts in Northwest, Mpumalanga, KwaZulu-Natal, Eastern Cape and Western Cape | Female sex workers |

|

| Eakle et al. (2018) [37] | Exploring acceptability of oral PrEP prior to implementation among female sex workers in South Africa | The paper aimed to explore community- level, multi-dimensional acceptability of PrEP within the context of imminent implementation alongside early ART in the TAPS Demonstration Project Qualitative study | Two clinic-based sites in Johannesburg and Pretoria | 69 participants (Female sex workers) |

|

| Eakle et al. (2019) [38] | “I am still negative”: Female sex workers’ perspectives on uptake and use of daily pre- exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention in South Africa | The paper aimed to explore the lived experiences and perceptions of taking up and using PrEP among FSWs engaged in the TAPS Demonstration Project Qualitative study | Two urban clinics (Johannesburg and Pretoria) | 18 participants (Female sex workers) |

|

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.2. Results of the Analyzed Studies

3.2.1. PrEP Promotion and Distribution

3.2.2. PrEP Counselling and Using Educational Resources

3.2.3. Using Instant Messaging and Rewards Programs

4. Discussion

4.1. PrEP Promotion and Distribution

4.2. PrEP Counselling and Educational Resources

4.3. Using Instant Messaging and Rewards Programs

5. Study Limitations

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Global HIV, Hepatitis and STIs Programmes; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. When Women Lead, Change Happens: Women Advancing the End of AIDS, 2017. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/when-women-lead-change-happens_en.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Moodley, D.; Esterhuizen, T.M.; Pather, T.; Chetty, V.; Ngaleka, L. High HIV incidence during pregnancy: Compelling reason for repeat HIV testing. AIDS 2009, 23, 1255–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carney, T.; Williams, P.M.P.; Plüddemann, A.; Parry, C.D. Sexual HIV risk among substance-using female commercial sex workers in Durban, South Africa. Afr. J. AIDS Res. 2015, 14, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parry, C.D.; Dewing, S.; Petersen, P.; Carney, T.; Needle, R.; Kroeger, K.; Treger, L. Rapid Assessment of HIV Risk Behavior in Drug Using Sex Workers in Three Cities in South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2008, 13, 849–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstant, T.L.; Rangasami, J.; Stacey, M.J.; Stewart, M.L.; Nogoduka, C. Estimating the Number of Sex Workers in South Africa: Rapid Population Size Estimation. AIDS Behav. 2015, 19, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grasso, M.A.; Manyuchi, A.E.; Sibanyoni, M.; Marr, A.; Osmand, T.; Isdahl, Z.; Struthers, H.; McIntyre, J.A.; Venter, F.; Rees, H.V.; et al. Estimating the Population Size of Female Sex Workers in Three South African Cities: Results and Recommendations From the 2013-2014 South Africa Health Monitoring Survey and Stakeholder Consensus. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2018, 4, e10188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassanjee, R.; Welte, A.; Otwombe, K.; Jaffer, M.; Milovanovic, M.; Hlongwane, K.; Puren, A.J.; Hill, N.; Mbowane, V.; Dunkle, K.; et al. HIV incidence estimation among female sex workers in South Africa: A multiple methods analysis of cross-sectional survey data. Lancet HIV 2022, 9, e781–e790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South Africa National Department of Health. Guidelines for Expanding Combination Prevention and Treatment Options for Sex Workers: Oral Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) and Test and Treat (T&T); South Africa National Department of Health: Pretoria, South Africa, 2016.

- South Africa National Department of Health. South Africa’s National Sex Worker, HIV, TB And STI Plan; South Africa National Department of Health: Pretoria, South Africa, 2019.

- World Health Organization. Consolidated Guidelines on the use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach 2016. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/208825 (accessed on 17 July 2024).

- Prevention, UN. Roadmap: Getting on Track to End AIDS as a Public Health Threat by 2030. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/prevention-2025-roadmap_en.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Pebody, R. Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP). AidsmapCom 2024. Available online: https://www.aidsmap.com/about-hiv/pre-exposure-prophylaxis-prep (accessed on 17 July 2024).

- Makhakhe, N.F.; MeyerWeitz, A.; Sliep, Y. Motivating factors associated with oral pre-exposure prophylaxis use among female sex workers in South Africa. J. Health Psychol. 2022, 12, 2820–2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abou Ghayda, R.; Hong, S.H.; Yang, J.W.; Jeong, G.H.; Lee, K.H.; Kronbichler, A.; Solmi, M.; Stubbs, B.; Koyanagi, A.; Jacob, L.; et al. A Review of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Adherence among Female Sex Workers. Yonsei Med. J. 2020, 61, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eakle, R.; Gomez, G.B.; Naicker, N.; Bothma, R.; Mbogua, J.; Cabrera Escobar, M.A.; Saayman, E.; Moorhouse, M.; Venter, W.F.; Rees, H.; et al. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis and early antiretroviral treatment among female sex workers in South Africa: Results from a prospective observational demonstration project. PLoS Med. 2017, 14, e1002444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dayton, R.L.; Fonner, V.A.; Plourde, K.F.; Sanyal, A.; Arney, J.; Orr, T.; Nhamo, D.; Schueller, J.; Limb, A.M.; Torjesen, K. A Scoping Review of Oral Pre-exposure Prophylaxis for Cisgender and Transgender Adolescent Girls and Young Women: What Works and Where Do We Go from Here? AIDS Behav. 2023, 27, 3223–3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramraj, T.; Chirinda, W.; Jonas, K.; Govindasamy, D.; Jama, N.; Appollis, T.M.; Zani, B.; Mukumbang, F.C.; Basera, W.; Hlongwa, M.; et al. Service delivery models that promote linkages to PrEP for adolescent girls and young women and men in sub-Saharan Africa: A scoping review. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e061503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhamel, J.; Rotsaert, A.; Reyniers, T.; Nöstlinger, C.; Laga, M.; Van Landeghem, E.; Vuylsteke, B. The current landscape of pre-exposure prophylaxis service delivery models for HIV prevention: A scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, J.L.; Russo, R.G.; Huang, A.K.; Jivapong, B.; Ramasamy, V.; Rosman, L.M.; Pelaez, D.L.; Sherman, S.G. ART uptake and adherence among female sex workers (FSW) globally: A scoping review. Glob. Public Health 2020, 17, 254–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castor, D.; Heck, C.J.; Quigee, D.; Telrandhe, N.V.; Kui, K.; Wu, J.; Glickson, E.; Yohannes, K.; Rueda, S.T.; Bozzani, F.; et al. Implementation and resource needs for long-acting PrEP in low- and middle-income countries: A scoping review. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2023, 26, e26110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mpirirwe, R.; Segawa, I.; Ojiambo, K.O.; Kamacooko, O.; Nangendo, J.; Semitala, F.C.; Kyambadde, P.; Kalyango, J.N.; Kiragga, A.; Karamagi, C.; et al. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis uptake, retention and adherence among female sex workers in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e076545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awungafac, G.; Delvaux, T.; Vuylsteke, B. Systematic review of sex work interventions in sub-Saharan Africa: Examining combination prevention approaches. TM IH Trop. Med. Int. Health 2017, 22, 971–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrich, K.; Freeman, G.K.; Richards, S.C.; Robinson, I.C.; Shepperd, S. How to do a scoping exercise: Continuity of care. Res. Policy 2002, 20, 25–29. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, S.; Thomas, A. An Introduction to Scoping Reviews. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2022, 14, 561–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, J.; Mukandavire, C.; Boily, M.C.; Fraser, H.; Mishra, S.; Schwartz, S.; Rao, A.; Looker, K.J.; Quaife, M.; Terris-Prestholt, F.; et al. Estimating the contribution of key populations towards HIV transmission in South Africa. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2021, 24, e25650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobrescu, A.I.; Nussbaumer-Streit, B.; Klerings, I.; Wagner, G.; Persad, E.; Sommer, I.; Herkner, H.; Gartlehner, G. Restricting evidence syntheses of interventions to English-language publications is a viable methodological shortcut for most medical topics: A systematic review. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 137, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Flaherty, J.; Phillips, C. The use of flipped classrooms in higher education: A scoping review. Internet High. Educ. 2015, 25, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Toward good practice in thematic analysis: Avoiding common problems and be(com)ing aknowing researcher. Int. J. Transgender Health 2022, 24, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makhakhe, N.F.; Sliep, Y.; Meyer-Weitz, A. “Whatever is in the ARVs, is Also in the PrEP” Challenges Associated With Oral Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Use Among Female Sex Workers in South Africa. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 691729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimbindi, N.; Mthiyane, N.; Zuma, T.; Baisley, K.; Pillay, D.; McGrath, N.; Harling, G.; Sherr, L.; Birdthistle, I.; Floyd, S.; et al. Antiretroviral therapy based HIV prevention targeting young women who sell sex: A mixed method approach to understand the implementation of PrEP in a rural area of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. AIDS Care 2021, 34, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillay, D.; Stankevitz, K.; Lanham, M.; Ridgeway, K.; Murire, M.; Briedenhann, E.; Jenkins, S.; Subedar, H.; Hoke, T.; Mullick, S. Factors influencing uptake, continuation, and discontinuation of oral PrEP among clients at sex worker and MSM facilities in South Africa. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mataboge, P.; Nzenze, S.; Mthimkhulu, N.; Mazibuko, M.; Kutywayo, A.; Butler, V.; Naidoo, N.; Mullick, S. Planning for decentralized, simplified prEP: Learnings from potential end users in Ga-Rankuwa, gauteng, South Africa. Front. Reprod. Health 2023, 4, 1081049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.; Mhlophe, H.; Pretorius, A.; Mcingana, M.; Mcloughlin, J.; Shipp, L.; Baral, S.; Hausler, H.; Schwartz, S.; Lesko, C. Effect of implementation strategies on pre-exposure prophylaxis persistence among female sex workers in South Africa: An interrupted time series study. Lancet HIV 2023, 10, e807–e815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eakle, R.; Bourne, A.; Mbogua, J.; Mutanha, N.; Rees, H. Exploring acceptability of oral PrEP prior to implementation among female sex workers in South Africa. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2018, 21, e25081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eakle, R.; Bothma, R.; Bourne, A.; Gumede, S.; Motsosi, K.; Rees, H. “I am still negative”: Female sex workers’ perspectives on uptake and use of daily pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention in South Africa. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Differentiated and Simplified Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis for HIV Prevention: Update to WHO Implementation Guidance; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fibriana, A.; Azinar, M. Peer Education: Increased Knowledge and Practice of HIV/AIDS Prevention in Female Sex Workers. In Proceedings of the 5th International Seminar of Public Health and Education, ISPHE 2020, Universitas Negeri, Semarang, Semarang, Indonesia, 22 July 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabata, S.T.; Makandwa, R.; Hensen, B.; Mushati, P.; Chiyaka, T.; Musemburi, S.; Busza, J.; Floyd, S.; Birdthistle, I.; Hargreaves, J.R.; et al. Strategies to Identify and Reach Young Women Who Sell Sex With HIV Prevention and Care Services: Lessons Learnt From the Implementation of DREAMS Services in Two Cities in Zimbabwe. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2022, 8, e32286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litiema, E.; Orago, A.; Muia, D. Correlates Associated With Adherence Among Female Sex Workers on HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis in Nairobi City County, Kenya. J. Health Med. Nurs. 2021, 7, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briedenhann, I.; Greensides, D.; Mullick, S.; Ferrigno, B.; Schirmer, A.; Subedar, H. Oral PrEP—IEC Material Development: Insights and Approaches. Wits RHI (University of the Witwatersrand) 2017. Available online: https://www.prepwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/SAAIDS_IECmaterials_OPTIONS.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- South Africa National Department of Health. Updated Guidelines for the Provision of Oral Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) to Persons at Substantial Risk of HIV Infection; South Africa National Department of Health: Pretoria, South Africa, 2021. Available online: https://knowledgehub.health.gov.za/system/files/elibdownloads/2023-04/PrEP%2520Guidelines%2520Update%252012%2520%2520Nov%2520%25202021%2520Final.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Serrano, V.B.; Moore, D.J.; Morris, S.; Tang, B.; Liao, A.; Hoenigl, M.; Montoya, J.L. Efficacy of daily text messaging to support adherence to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among stimulant-using men who have sex with men. Subst. Use Misuse 2023, 58, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celum, C.L.; Delany-Moretlwe, S.; Baeten, J.M.; van der Straten, A.; Hosek, S.; Bukusi, E.A.; McConnell, M.; Barnabas, R.V.; Bekker, L.G. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis for adolescent girls and young women in Africa: From efficacy trials to delivery. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2019, 22, e25298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, R.T.; Ritvo, P.; Mills, E.J.; Kariri, A.; Karanja, S.; Chung, M.H.; Jack, W.; Habyarimana, J.; Sadatsafavi, M.; Najafzadeh, M.; et al. Effects of a mobile phone short message service on antiretroviral treatment adherence in Kenya (WelTel Kenya1): A randomised trial. Lancet 2010, 376, 1838–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velloza, J.; Donnell, D.; Hosek, S.; Anderson, P.L.; Chirenje, Z.M.; Mgodi, N.; Bekker, L.G.; Marzinke, M.A.; Delany-Moretlwe, S.; Celum, C. Alignment of PrEP adherence with periods of HIV risk among adolescent girls and young women in South Africa and Zimbabwe: A secondary analysis of the HPTN 082 randomised controlled trial. Lancet HIV 2022, 9, e680–e689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celum, C.L.; Mgodi, N.; Bekker, L.G.; Hosek, S.; Donnell, D.; Anderson, P.L.; Dye, B.J.; Pathak, S.; Agyei, Y.; Fogel, J.M.; et al. PrEP adherence and effect of drug level feedback among young African women in HPTN 082. In Proceedings of the International AIDS Society Conference (IAS), Mexico City, Mexico, 21–24 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Makhakhe, N.F.; Khumalo, G. Mapping Evidence on Strategies Used That Encourage Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Uptake and Adherence Amongst Female Sex Workers in South Africa. Sexes 2025, 6, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6010002

Makhakhe NF, Khumalo G. Mapping Evidence on Strategies Used That Encourage Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Uptake and Adherence Amongst Female Sex Workers in South Africa. Sexes. 2025; 6(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleMakhakhe, Nosipho Faith, and Gift Khumalo. 2025. "Mapping Evidence on Strategies Used That Encourage Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Uptake and Adherence Amongst Female Sex Workers in South Africa" Sexes 6, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6010002

APA StyleMakhakhe, N. F., & Khumalo, G. (2025). Mapping Evidence on Strategies Used That Encourage Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Uptake and Adherence Amongst Female Sex Workers in South Africa. Sexes, 6(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6010002