Abstract

Japan, having had the longest isolationist policy in the world, is averse to options, such as migration to increase the population. What kinds of pronatalist policies to increase fertility and lower the population’s age are ethical? Two questions can be raised: is it ethical for the government to intercede, and is it ethical for individuals to exercise this choice? In addition to the gradually decreasing birth rate, Japan is faced with the challenge of a possible sharp decline in the birth rate in 5 years. Astrology and superstition have influenced the sex preference of a child in Japan, and in 1966, there was a 26% drop in the birth rate. It was the year of Hinoeuma, occurring at 60-year intervals, and women born that year are believed to have a potentially dangerous ‘headstrong temperament’ and murder their husbands. Abortion rates spiked that year, and many forged the birth date of their child. The next Hinoeuma is in 2026. Although the bioethical debate about pronatalism exists in the literature, there is no literature addressing the question of sex selection in the context of a decreasing population. This paper argues that even if the Japanese government’s current pronatalist approach is ethically warranted, it should not extend to sex selection since it would promote misogyny and stereotypical gender roles.

1. Introduction: History of the Hinoeuma Year Superstition

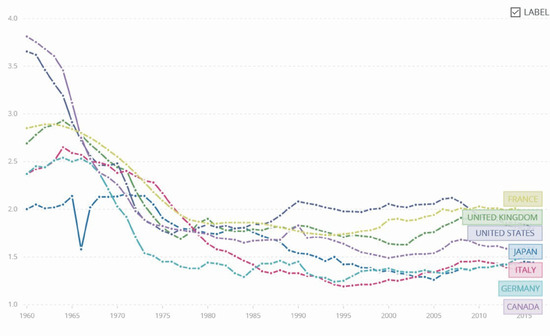

The Hinoeuma (丙午), a combination of the characters for hinoe (‘fire’) and uma (‘horse’), is one of the 60 zodiac combinations in Chinese astrology [1]. The 60 combinations are made from the 5-year cycle of elements (wood, fire, water, metal and earth) with the 12-year cycle of astrological animals. The superstition of the Hinoeuma year in Japan is quite old and can be traced back to 1686, when a novelist, Ihara Saikaku, wrote about a young, headstrong woman born in 1666 who was executed for arson to be reunited with her lover [2]. This story led to the belief that women born in the year of the Hinoeuma, the fire-horse coincidence, are temperamental and make unsuitable wives. The superstition has persisted and affected the Japanese demographic structure even after the 19th-century opening of Japan to the West. Birth rate reductions in 1846, 1906, and 1966, each of which was a Hinoeuma year, demonstrate the superstition’s influence [1,2,3]. In 1906, Japan’s birth rate declined by 7% owing to abstinence or forging of birth certificates to reflect a different year. In 1966, birth rates declined 26% due to abstinence and increased abortion rates (43.1 abortions/1000 births, higher than the average rate of 30.5 abortions/1000 births for 1963–1969) [4]. A sudden dip in the birth rate in 1966 facilitated the easy determination of the fertility curve for Japan (Figure 1). Mothers familiar with this superstition were afraid that their future daughters could not get married and deferred having babies that year altogether. With the start of January 1966, the birth rate declined from 17.3 in December 1965 to 14.6 in just a month [3]. The next Hinoeuma is in 2026, and if the Hinoeuma superstitions still persist among Japanese citizens, a serious decline in births may occur. Furthermore, there may be an increase in the selective abortions of female babies through prenatal diagnosis based on superstitions. Ethically, such actions are problematic. The level of technology that can assist with reproduction in 2026 is different from what existed in 1966. During the last Hinoeuma year, in 1966, there were only two methods that existed in relation to preventing female births, namely total induced abortions (not sex-selective), abstinence, or a condom (the pill became available after 1999). Currently, reliable methods of sex selection in utero are available. Since the late 20th century, prenatal (using either non-invasive or invasive) testing, preimplantation genetic testing, and preconception testing are now possible with the use of technology.

Figure 1.

Fertility rate, total (births per woman) for G7 countries. Source: The data up to 2017–1959 are based on the World Bank Data Bank and created through their website (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN, accessed on 28 January 2023).

A direct solution to Hinoeuma sex selection is in utero, which involves issues of sex-selective abortion. To resolve the Hinoeuma issue, the superstition needs to be expelled from Japanese society, whether people are only half-believers of this superstition. However, this requires long-term efforts from professional societies and governments, and the method is undetermined. In an aging society with a seriously decreasing birth rate such as Japan, abstinence is no solution. Sex-selective abortion is unethical and beyond our discussion. Therefore, sex selection in vitro (such as preimplantation genetic testing, PGT) is the only method to not become pregnant with a female offspring and become pregnant with a male. This balances well with the Hinoeuma superstition, as well as escapes ethical discussion of abortion, and may alleviate the decreased birth rate in Japan. By 2026, would there be an increased demand for PGT to select for the male sex? As opposed to abortion, this is ethically acceptable; however, there may be objections to its aggressive promotion. This communication paper discusses the essential structure of the Hinoeuma problem in Japan by examining the institutional feasibility and ethical validity of in-utero sex selection in Japan. Furthermore, we discuss the socio-ethical issues with sex selection in general in Japan using the adoption of PGT as a direct solution to the Hinoeuma problem.

2. Discussion

2.1. The Japanese System of Sex Selection

Currently, the Japanese Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (JSOG)-registered gynecologists are prohibited under the law from using sex-selection technologies for non-medical reasons. Only three fatal X-linked genetic conditions are currently approved for medical sex selection [5]. Even sperm sorting was prohibited until recently. However, in light of the impending serious population decline facing Japan, extending the use of these technologies might well be politically justified. In 2017, the ratio of children to the overall population dipped to a record low of 12.3 percent, down for the 44th straight year [6]. Among the 32 countries with populations of 40 million or more, Japan had the lowest ratio, even lower than Germany and South Korea, according to the United Nations Demographic Yearbook [6]. The fertility rate has been decreasing and reached a low of 1.43 in 2018, sometimes referred to as a ‘coffin type’ population pyramid [2,6]. The 1990 drop in fertility rate to 1.57, the lowest in the previous century, initiated governmental involvement to resolve this decline [7]. Then-Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and his predecessors attempted to halt the decline by giving governmental support for matchmaking parties, partial coverage of fertility treatments, stipends for delivering a child, childcare coverage, and even a child stipend, all without success [8]. A city even subsidized social egg freezing several years ago [9]. Their aim was to increase Japan’s fertility rate to 1.8 by the mid-2020s [7]. If Japan is concerned about increasing the number of births, it would no doubt be appealing to the Japanese government to legalize or even promote the sex-selective conceptions aimed at minimizing the decline in the number of male births in order to reduce the decline in the number of births in the 2026 Hinoeuma as much as possible.

However, such a pronatalist approach itself should first be criticized. Globally, pronatalist approaches have included intensive propaganda, financial reimbursements, immigration control, social benefits, limiting birth control, conservative abortion laws, banning sterilization and enforcement of eugenic laws. The most extreme measures were taken by socialist Romania in 1966–1989, where contraception was made almost inaccessible, and abortion was banned. These have received much criticism in terms of justice and violating women’s autonomy. However, even so, women’s procreative autonomy over becoming mothers is under much social pressure.

Furthermore, the promotion of sex-selective conceptions is not consistent with Japan’s existing social system. Japanese society (as represented in the JSOG guidelines), compared to many Western societies, has strictly restricted testing only for particular fatal medical conditions, such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy [5]. Prenatal testing has been discouraged overall. After much public confusion caused by the introduction of serum marker screening tests in the 1980s, the Japanese government warned physicians to avoid actively recommending prenatal testing; physicians are not required to inform patients even about the availability of the testing [10]. In non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT), available in the Japanese market since 2013, only 3 conditions (trisomy 21, 18 and 13) are tested for, and fewer than 10 conditions have been allowed for preimplantation genetic testing (PGT) [11,12]. JSOG policy is ‘very careful’ about the selection of conditions allowed for testing [11]. Only 7.2% of pregnancies in Japan undergo prenatal screening, perhaps as a result of these restrictions [13]. The number of conditions has been gradually increasing, especially with the introduction of NIPT in 2013 [13,14]. Though the NIPT consortium recommends against sex-chromosome testing, a few private clinics outside the consortium are testing for sex. Many patients, such as those in the U.S., are opting for these clinics so that they will know the gender of their baby. During the next Hinoeuma year, having the option of sex-selective technologies could pressure parents to make a choice they do not really want to make, simply to alleviate the pressure of not ‘risking’ having a Hinoeuma daughter. In addition, the decision for sex selection would require changing Japanese abortion law. Abortion is not allowed for fetal conditions. Current law allows abortion for (1) maternal social-economic and health reasons affecting pregnancy or (2) as a result of rape [15]. Abortion for fetal conditions has, until now, been masked by labeling it as socio-economically and psychologically burdensome to raise a child with a deleterious condition. It is clear that if sex selection for non-medical reasons were tolerated, it would contradict Japanese law. It could also entail the governmental promotion of societal discrimination against women, as well as further encourage a negative superstition about women born in a Hinoeuma year.

2.2. Ethical Obligations for Prospective Hinoeuma Year Parents: Preference for Sons

While the promotion of sex-selective conceptions would be beneficial to the Japanese government, the current state of the Japanese social system will not allow it to be easily realized. Considering the Japanese system, as well as the limitations to the context of the current Japanese situation, can the promotion of sexual selection be ethically justified in the first place? Additionally, what are the issues that arise as a result of promoting sex selection?

At first glance, the promotion of sex-selective conceptions appears to be justifiable from a utilitarian perspective. Liberalizing or promoting sex selection does not cause any harm to others; abortion in Hinoeuma, however, definitely causes harm to the fetus. In this regard, the use of sex-selective conceptions techniques to avoid abortion is desirable. Furthermore, it contributes to the promotion of welfare as parents are then able to have a child of their desired gender. In addition, does an ethical obligation exist for prospective parents to have sons and avoid harm to Hinoeuma daughters? The answer is yes if prospective parents of children to be born in 2026 value marriage as much as parents in 1966 did and feel morally obligated both to have a male child and to prevent the births of non-eligible daughters. The ideal role of women in the 1960s was to get married by 24 years of age (women who remained unmarried beyond that age were degraded and termed ‘Christmas cake’ being over 25) and become supportive wives to their children and husband (this meant quitting her profession after marriage, or entering marriage retirement). In 1966, the annual rate of marriage was 9.5 (per 1000 people); in 2015, it decreased almost by half to 5.1 (per 1000 people) [16]. In the 1960s, approximately 90% of couples in which both partners were aged 30–34 years were married; in 2015, only about 53% of men and 65% of women were married [16]. Though the current survey shows that marriage may today be an institution that is less sought out by a larger share of younger Japanese people, especially urban youth, compared to 1966, marriage is still viewed positively by many parents [16].

Savulescu argues that all parents have a procreative responsibility to create children to have the best chance to have the best possible life, and therefore sex selection should be available [17]. Thus, parents will ultimately be responsible when 2026 comes for selecting a son or forgoing pregnancy if they accept the superstition and believe that sons born in that Hinoeuma year can have a better life than daughters born in that year can have. However, will Hinoeuma sons have a better chance to marry than Hinoeuma daughters? Retrospective research done by Akabayashi in 2007 shows that marriage rates decreased for both Hinoeuma men and women born in 1966, while this decrease was compensated for by higher rates of marriage to women born before (1965) and after (1967) that Hinoeuma year, this effect was not seen for the men [10]. Akabayashi proposed that the decrease in marriage for men born in 1966 was not compensated since they were more superstitious about marrying women born in the same year, while Hinoeuma women were able to marry men born in different years since they were not superstitious. Marriage rate declines were more significant for Hinoeuma men [2,10]. This has been attributed to Hinoeuma men suffering decreased marriage opportunities by discriminating against women in their own cohort [9], as well as there being fewer women in their cohort. Akabayashi’s findings suggest, contrary to the Hinoeuma superstition, that simply choosing to have a male son rather than a daughter may not result in a better life for the child, according to the parents who perceive marriage as a positive quality.

Parents’ choice of pre-selecting a male might harm the son by decreasing his chance of marriage. However, a later study by Shimizutani and Yamada in 2014 comparing Hinoeuma women with cohort women born in the surrounding years showed Hinoeuma women had higher divorce rates, lower educational attainment (2-year college graduates), and lower income when they reached the age of around 44 [18]. This has been attributed to the possible long-term discrimination towards Hinoeuma women. These results may be enough to convince parents to forgo pregnancy altogether, decreasing the birthrate once again in 2026. Sex selection in the Hinoeuma year 2026 under the intention of becoming a responsible, well-intended parent may mean choosing between prejudiced sons who ultimately cannot get married or discriminated daughters who will more likely become divorced.

2.3. Moral Obligations for Japanese Women to Have a Child: Preference for Daughters

Considering the seriousness of the contemporary decline in the overall birth rate, it is important to first consider whether there may be a moral obligation for Japanese women to have a child in general and whether there is any gender preference, regardless of such superstition-based projections about the child’s well-being in adulthood. Given the Japanese government’s pronatalist approach and even easing immigration laws for workers in order to support the increasingly aged population for a historically homogenous country, women are being increasingly pressured to socially accept this obligation. In addition, women who declare the right not to have children are considered ‘shallow’, ‘immature’, and ‘selfish’ [19]. Since companies and government have been offering more childcare, married people—especially women—who do not have children feel harassed by society [19]. Classified as “childless (ko-nashi)”, these women are relied upon to provide significantly longer hours of work and feel obligated to cover for women with children, told by their peers to undergo fertility treatment, and even divorce and remarry if their partner was possibly infertile. While resistance toward these societal pressures exists, women who exercise the right not to have children are under much criticism—even as far as ‘not fulfilling the responsibility as a human being’ [19]. There is also tension between women who have children and those who choose not to have children since their children would ultimately grow up to be payers of the social security and income taxes that will cover the care of the “childless” people as well as of those who had children, particularly in illness and retirement. Moreover, given the strong Japanese work ethic, women feel responsible and expected to work with the same amount of rigor, working extensive and irregular hours, even after having children. This conflict with the latent work ethic becomes more prominent when the child enters elementary school and has longer vacations and shortened hours of care, restricting the hours of work for women.

Recent surveys show that there is a general daughter preference [20]. Traditionally, similar to other East Asian countries, Japan used to have a son preference owing to patriarchal influence. Surveys show that since the late 1980s, many single men and women have shifted their personal desire to having a daughter as their first child [20]. Given societal obligations to have children and the need to work full-time raising the children, Japanese women now prefer daughters to sons: they are desperate for help within the family. It has been suggested that the daughter preference is not because of gender equality but because of inequality [20]. The idea of the motherly virtue of caring for one’s children without help outside the family is a persistent notion in Japan and puts women in check. Men in Japan reportedly do fewer hours of housework and child care than in any of the world’s richest nations. Although 67% of the women in Japan work, women working full-time do 5 times more housework than their husbands [21]. While women take on much of the childcare, obtaining help is not easy. Having a nanny is not common, and being accepted in public daycare facilities, especially in Tokyo, is highly competitive due to a shortage of facilities. If a child does not obtain a spot for the 0-year-old class, it becomes close to impossible to get a spot until the child turns four, when the enrolment capacity increases due to the mandatory kindergarten age. Therefore, many working women attempt to become pregnant with delivery dates closer to and after April, when the Japanese academic year begins, since many mothers want to stay with their children as much as possible [22]. Since most nursery’s eligibility is from 4 months of age, there are hardly any enrolled children who are born after January enrolled in public daycare.

In Japanese culture, ichihime-nitaro (‘first a girl then a boy’) is a commonly held belief that was originally a phrase to put mothers whose firstborn was a daughter in a patriarchal society at ease. Daughters are seen as the ideal for the first child since they are generally healthier, easier to raise, and most importantly, sought after for their gender role: being helpful as caretakers to the male siblings that follow or to the parents in old age, as well as being better companions. The Japanese General Social Survey (JGSS), a national public opinion survey of adults 20 years of age or older, also asked respondents whether they wanted a boy or a girl if they were to have only one child [20]. Survey results from 2000 indicated that among men, 61% wanted a boy and 35% wanted a girl, while among women, 26% preferred a boy and 70% wanted a girl child [20]. This survey, analyzed by Fuse, concludes that this daughter preference is not simply a reflection of improvements in women’s status. It is, in fact, the opposite: it is the reflection of the persistent divergence in gender roles that remains in Japan [20]. This could be related to how the Hinoeuma superstition evolved: mothers had more responsibility for passing the superstition to their offspring [2]. While allowing sex selection may be a temporary relief for the seriously decreasing population, the stereotypical mindset or expectations for the child’s gender will persist.

A liberty-based argument in support of sex selection might begin with the premise that free choice is ethically justified unless allowing it harms others [23]. This type of argument is more morally persuasive in countries such as the U.S., where emphasis on personal autonomy and liberty is highly prized and where sex selection for a variety of reasons is considered ethically justified, e.g., for ’family balancing’. Unlike Japan, in the U.S., there is no evidence to date of large-scale gender imbalance resulting from sex selection practices [24]. However, in Japan, two harmful social implications of sex selection can be projected: (1) it will skew the national sex ratio toward females, and (2) it perpetuates the divergence of gender roles in Japanese society. Approximately 90% of Japanese who had traveled abroad (U.S., Korea, and Thailand) to undergo sex selection because it is prohibited in Japan desired daughters [5]. If sex selection becomes permitted in Japan, a skew of firstborn children toward daughters can easily be imagined. Given Japanese women’s high life expectancy, the skew can worsen concerns about the ageing population. One could simply justify the positive effect of having more women as improving the social status of women since more women would be responsible for the economy and would push to converge gender roles. The outcome of societies with higher female births is unknown since there are no past examples; however, Russia’s population sex ratio has been 0.86 male(s)/female, since male life expectancy is 11.6 years less than women, attributed to lifestyle (excessive drinking and smoking) [25]. Yet, in terms of the Global Gender Gap report, Russia ranks 75th out of 149 countries, not that much different than Japan, which ranks 110th [21,25]. If sex selection were allowed, women would use it to produce female offspring to help them with the household, thus promoting the persistence of further gender inequality and even the disruption of the sex ratio. Prospective mothers need to realize the harmful consequences to their potential daughters and to society.

3. Conclusions

Daughters born in 1966 Hinoeuma were more successful in marriage, though they were more likely to divorce and have lower economic status in the long run as a result of discrimination toward them [18]. In the 2026 Hinoeuma, the first goal should be to dispel superstition. Of course, after 60 years, and with the gradual loss of old Japanese customs, one would think and hope that an increasing number of parents would not be misled by traditional superstitions. However, old customs still tend to remain influential in rural areas, and at present, it is not clear whether the number of births will decline. As the next best option to avoid an absurd number of abortions from occurring and to halt the decline in the number of births, a simple idea could be that allowing prospective parents to choose their child’s sex in 2026 would avoid unnecessary abortions and limit the decline in the birth rate. However, the existing Japanese social system prevents this, and there are also problems with gender selection itself—such as the question asked from a utilitarian perspective. Parents who choose to select Hinoeuma sons need to be aware of the real possibility of harm due to not being able to marry women from their own cohort, which leads to social stigmatization. The other problems are the stigmatization of genders and the hidden discriminatory structures in Japan.

The government should sustain its focus on promoting gender equality and resolving the social stigma associated with Hinoeuma women as an ultimate pronatalist approach. Unlike the West, the legalization of sex selection in Japan would likely result in practicing sex selection out of the observance of traditional gender roles. For 2026, other pronatalist approaches to social solutions to the declining birthrate need to be considered. Since sex selection would perpetuate the misogyny underlying the Hinoeuma superstition, the Japanese government should resist it. Admittedly, prohibiting sex selection is not the only, or even the most important, tool to fight gender stereotypes and inequality. However, it is one important pathway. In the long run, the government needs to strive to resolve the deeply rooted, male-privileged ‘customs’ that create so many life-long burdens for Japanese women. Future generations of Japanese women deserve no less.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.T. and E.N.; methodology, S.T. and E.N.; resources, S.T.; writing—original draft preparation, S.T.; writing—review and editing, S.T. and E.N.; project administration, E.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank Akira Akabayashi, Lainie F. Ross, and Nancy S. Jecker for the valuable comments that greatly improved the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Grech, V. The Influence Of The Chinese Zodiac On The Male-To-Female Ratio At Birth In Hong Kong. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2015, 78, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, C.; Iwasa, Y. Cultural evolution of a belief controlling human mate choice: Dynamic modeling of the Hinoeuma superstition in Japan. J. Theor. Biol. 2012, 309, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koya, A. The Mysterious Drop in Japan’s Birth Rate. Society 1968, 5, 46–48. [Google Scholar]

- Kaku, K. Increased induced abortion rate in 1966, an aspect of a Japanese folk superstition. Ann. Hum. Biol. 1975, 2, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibuki, T. Should PGD for sex-selection be allowed in the Japanese context? A literature review and critical analysis of the bioethical arguments. Jpn. Assoc. Bioeth. 2014, 24, 244–254. Available online: https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jabedit/24/1/24_KJ00009962008/_pdf/-char/ja (accessed on 23 February 2019). (In Japanese).

- The Ministry of Health Labor and Welfare. Mhlw.go.jp. 2018. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/jinkou/suikei18/dl/2018suikei.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2019).

- The Japan Times. Japan’s Child Population Shrinks to 15.53 Million, Setting Another Record Low. 2018. Available online: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2018/05/04/national/number-children-japan-falls-37th-year-hit-new-record-low/#.W1bG3dL7RPY (accessed on 14 July 2018).

- Current Status of Countermeasures against Declining Birthrate (Part 1). Cabinet Office. 2017. Available online: https://www8.cao.go.jp/shoushi/shoushika/whitepaper/measures/english/w-2017/pdf/part1-1.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2019).

- Japanese City Helps Women Freeze Eggs to Boost Birth Rate. BBC News. 2016. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-36551807 (accessed on 22 July 2019).

- Akabayashi, H. Who Suffered from the Superstition in the Marriage Market? The Case of Hinoeuma Women. 2006. Available online: http://www.cirje.e.u-tokyo.ac.jp/research/workshops/micro/documents/micro0717.pdf (accessed on 28 January 2023).

- Kousei Kagaku Shingikai Sentaniryo Hyoukagikai Shutseizen Shindan ni Kansuru Iinkai “Botai Ketsei Marker ni Kansuru Kenkai”ni Tuiteno Keika Hatshutuni Tsuite; Ministry Health, Labor and Wealfare; Ministry Health, Labor and Wealfare: Tokyo, Japan, 1999. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/www1/houdou/1107/h0721-1_18.html (accessed on 12 February 2019).

- Sato, K.; Iino, K.; Senba, H.; Suzuki, M.; Mizuguchi, Y.; Izumi, Y.; Sato, S.; Nakabayashi, A.; Tanaka, M. Current status of preimplantation genetic diagnosis in Japan. Bioinformation 2015, 11, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NIPT Nintei Shisetsu to Muninnkashisetsu no Hikaku. NIPT Consortium, Japan. 2017. Available online: https://authorizednipt.jimdo.com/ (accessed on 14 February 2019).

- Chiba, N. Number of Prenatal Screening Tests in Japan Jumps 2.4 Times in 10 Years. The Mainichi. 2018. Available online: https://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20181228/p2a/00m/0na/004000c (accessed on 14 February 2019).

- Japanese Law Translation—[Law Text]—Maternal Health Act. Japaneselawtranslation.go.jp. Available online: http://www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp/law/detail/?id=2603&vm=04&re=02 (accessed on 24 February 2019).

- Ryall, J. DWCOM. Available online: https://www.dw.com/en/why-fewer-japanese-are-seeking-marriage/a-19349576 (accessed on 14 February 2019).

- Savulescu, J. In defense of selection for nondisease genes. Am. J. Bioeth. 2001, 1, 6–19. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10822/943195 (accessed on 14 February 2019). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizutani, S.; Yamada, H. Long-Term Consequences Of Birth In An ‘Unlucky’ Year: Evidence From Japanese Women Born In 1966. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2014, 21, 1174–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneshiro, T.; Kaneta, R. Konashi Harasumento (Harassment for not having children). Asahi Shinbun Wkly. AERA 2015, 18, 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Fuse, K. Daughter preference in Japan: A reflection on gender role attitudes? Demogr. Res. 2013, 28, 1021–1052. Available online: https://www.demographic-research.org/volumes/vol28/36/28-36.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2019). [CrossRef]

- Rich, M. Japan’s Working Mothers: Record Responsibilities, Little Help From Dads. The New York Times. 2019. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/02/world/asia/japan-working-mothers.html (accessed on 14 February 2019).

- Tabuchi, H. Desperate Hunt for Day Care in Japan. The New York Times. 2019. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2013/02/27/world/asia/japans-mothers-in-hokatsu-hunt-for-day-care.html (accessed on 28 January 2023).

- Mill, J.S. On Liberty; John Parker and Sons: London, UK, 1857. [Google Scholar]

- Kalfoglou, A.; Kammersell, M.; Philpott, S.; Dahl, E. Ethical arguments for and against sperm sorting for non-medical sex-selection: A review. Reprod. BioMedicine Online 2013, 26, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Data Explorer. Global Gender Gap Report 2018. 2019. Available online: http://reports.weforum.org/global-gender-gap-report-2018/data-explorer/ (accessed on 19 February 2019).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).