Abstract

Research on sexual diversity in physical education (PE) focuses primarily on students and rarely on teachers. Against this background, this study takes a look at teachers and explores the question of how lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) teachers experience PE. Our study was conceived as a systematic literature review of qualitative studies published between 1990 and 2022. The processual study selection was carried out according to PRISMA. A total of nine studies were identified that met our inclusion criteria. We analyzed and compared the findings of these studies. On an overarching level, our analysis shows that the identified studies predominantly focus on the challenges and problems associated with the sexuality of LGB teachers. Furthermore, our analysis shows that the PE teachers interviewed in the studies perceive and anticipate school as a homophobic context. From the teachers’ perspective, PE is a special subject that they experience as particularly risky due to their sexuality. Against the backdrop of these experiences, many PE teachers use protective strategies, which mainly consist of hiding their own sexuality and ignoring the perceived homophobia. In the end, research implications are discussed, highlighting the need for ongoing research on LGB PE teachers.

1. Introduction

The topic of sexual diversity has gained importance in school and educational research in recent years. Numerous studies have been published dealing with sexual diversity in the context of school [1,2,3,4]. At the level of education policy, the main objective is to implement sexual diversity in schools as an educational content. This implies the goal of enabling the participation of LGBTQ+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, etc.) students, promoting inclusion and overcoming discrimination. Existing studies show that teachers play a crucial role in establishing an open attitude towards sexual diversity and in preventing discriminatory behavior in schools, also because they are caregivers for students who can imitate and follow as an example [1,5,6].

The topic of sexual diversity has also come into focus in school sports research in the last few years [7]. Several studies have shown that physical education (PE) is a particularly challenging subject for LGBTQ+ students due to its characteristic body-centeredness [8,9]. There is evidence that LGBTQ+ students often feel marginalized and discriminated against in PE [10,11,12,13], although some studies indicate a decrease in discrimination [14]. This is particularly due to the fact that body shapes, movement images and physical performance capabilities in PE are always perceived, interpreted and evaluated in terms of gender. Gender-related perceptions often show up in heteronormatively colored attributions that are repeatedly evoked by the stakeholders of PE (teachers and students) in the context of teaching practices (such as gender-stereotypical sport preferences or gender-differentiating performance assessments) [15,16]. Heteronormativity refers to a worldview that postulates heterosexuality as a social norm. It is based on a binary gender order in which biological sex is equated with gender identity, gender role and sexual orientation. In a heteronormative view, homosexuality (or, in a broad understanding, any non-heteronormative form of life) is interpreted as a threat to the dual gender system [17]. Taking into account previous research, PE can be described as a field of action in which heteronormative gender is reproduced by reifying heterosexuality and marginalizing or often denigrating homosexuality [18].

Although there is a growing body of research on sexual diversity in PE and some studies on the experiences of lesbian PE teachers are available (e.g., [19]), to our knowledge no recent comprehensive study has been published that focuses on the experiences of lesbian/gay/bisexual (LGB) PE teachers. In contrast, two current reviews reconstruct the PE experiences from the perspective of LGBTQ+ students [10,20]. However, it is questionable to what extent the PE experiences differ or are possibly the same between LGB students and teachers.

Our study examines PE from the perspective of LGB teachers and summarizes qualitative studies as a part of a systematic review. The following questions are central: How do LGB teachers experience PE according to previous studies and which overarching themes regarding their experiences can be identified? Accordingly, the objective of our study is to identify qualitative studies published in peer-reviewed journals since 1990 on the topic of PE from the perspective of LGB teachers through a systematic literature search. Furthermore, we will review the qualitative studies and present superordinate findings by analyzing and comparing the findings from the previous studies. In addition, our study intends to identify research gaps and offer indications for future research.

2. Sexual and Gender Diversity in PE and at School

Sport pedagogical and didactic studies traditionally focus on PE teachers. Established areas of PE teacher research are teaching methodologies, teachers’ attitudes, patterns of stress and coping strategies, subjective objectives and orientations of PE, job satisfaction, teaching professionalism, questions of knowledge transfer and differential learning support, as well as professional biographical developments [21,22,23,24,25]. Thus, the research concerns essentially relate to the everyday life of PE, the professionalism of the teachers and the professional biography. It can be assumed that in the context of the developmental dynamics of modern societies, which continuously trigger changes in society as a whole, but also processes and upheavals in the culture of sport and physical activity and in the education system, these topics will continue to be highly relevant for sport pedagogical debates in the future.

Against the background of processes of societal pluralization, PE is increasingly being framed by normative programs for inclusive and diversity-sensitive practices and it follows the perspective of being able to organize sports and physical activities in a way that is appropriate for the target group. These programs focus on a critique of power relations and discrimination. The topic of ‘diversity in PE’ has been addressed in particular with regard to the diversity of students [26,27]. In the course of the UN “Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities” and the associated developments towards inclusive schools, discussions on individual differentiating dimensions of students, such as gender and ethnicity, have been increasingly narrowed down to the dimension of disability. The overarching goal of the concept of inclusion is to design PE in such a way that everyone can participate individually and is supported, thus ensuring equal participation for all [28]. Methodological–didactic reflections on the concept of inclusion take up this normative claim and address the problem of emphasizing individual categories by raising awareness of the fact that differentiation can be discriminatory. This goes hand in hand with the demand for greater consideration of diversity—in the sense of a broad understanding of inclusion that follows the assumption that persons in a learning group differ from one another with regard to a variety of characteristics that are considered relevant to learning. Differentiation of students by PE teachers is considered necessary in order to develop appropriate measures for individual support, but should in no way lead to students being limited in their developmental possibilities. For teachers, balancing individualization and differentiation is a central principle of teaching in heterogeneous groups [29]. Here, the concept of inclusion ties in with the concept of individualization, which has already been elaborated in greater depth in the context of differential or experiential learning [30].

In addition to the dimensions of difference such as physical condition, the heterogeneity category of gender is the focus of school sport research. Studies on the topic of gender in PE provide differentiated findings to the extent that gender is particularly relevant in PE and that a gender dichotomy is constructed in a specific way in interactions within PE [16]. In the course of the introduction of co-educational teaching in the middle of the 1970s, which was particularly controversial in the subject of PE, a large number of didactic contributions on the topic of gender equality emerged [31]. In the context of its body focus and diverse opportunities for social learning, co-educational PE was seen as having the special potential to break down traditional gender roles. In approaches of gender-sensitive teaching [32], the dichotomous view (girls/boys) of gender has been increasingly softened and rather linked to individual abilities and prerequisites of students. In an intended reflexive approach to the category of gender as a pedagogical–didactic guiding idea, the aim is to overcome gender-stereotypical ideas by consciously and productively dealing with the category of gender in the classroom. Thereby, some studies investigate the significance of teachers’ gender in the context of teaching practices. Among other things, it is emphasized that PE teachers’ gender has an impact on the relationship to students. Discrimination against female PE teachers is discussed, whereby the professional status is devalued by the culturally subordinate status of women [33].

The topic of sexual and gender diversity—as a differentiated or pluralistic conception of sexualities and gender identities beyond heteronormative thinking, which puts LGBTQ+ students and teachers in the spotlight—has recently been the subject of empirical research [6,7,12,34,35]. International studies point to a still difficult situation of LGBTQ+ students in school [36,37], with the subject of PE as a ‘traditionally heteronormative environment’ [6] regularly described as particularly problematic [10,12,20]. Following on from this, the first pedagogical concepts on sexual education in PE [38,39] are increasingly addressing the particular heteronormativity of the field, e.g., in the sense of ‘queer inclusive physical education’ [40].

The topic of LGB teachers is currently still unaddressed with regard to PE in German-speaking countries. The marginalization of this topic is in discrepancy with the now differentiated state of knowledge on homophobia in sport, which, however, primarily refers to organized extracurricular sport [41,42]. On an international level, however, individual studies on queer teachers in general are available [43,44,45,46,47,48,49]. These studies show that lesbian teachers face an ongoing trend of silencing, marginalization and discrimination in the workplace [44,45]. Additionally, studies indicate that queer teachers exist within a ‘space of exclusion’ that is dominated by discursive mechanisms that (re)produce heteronormativity [47]. Other studies examine the ‘coming out’ decisions of LGB teachers and argue that such decisions are complicated by heteronormative discursive practices within schools [46]. Findings from recent studies suggest that LGB teachers undertake complex identity work to maintain their status as LGB and as exemplary teachers [49,50]. Furthermore, some of the studies describe different behaviors that LGB teachers use to manage their sexuality in school, including the development of different teacher personas [46]. The studies mentioned focus on queer teachers in general and not on PE teachers. The question of how LGB PE teachers experience and reflect on PE according to previous studies is addressed in this review.

3. Methods

We conducted a systematic qualitative review following the PRISMA guidelines [51]. Our systematic review was not registered in the “International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews” (PROSPERO). Methodologically, we oriented towards various works [52,53,54]. In the context of a literature review, the selection of suitable databases for the literature search is of immense importance [54]. We selected relevant social science and sport science databases (Web of Science, ERIC, Scopus and SURF) and screened them for published qualitative research on PE from the perspective of LGB teachers in October 2022. The search was limited to publications from 1990 onwards because we assume that, due to social change, attitudes towards LGB in the 1970s and 1980s were fundamentally different from today, and that findings from before 1990 are only of limited relevance nowadays. In the search masks of the English databases, we entered the keywords ‘lesbian*’ or ‘gay*’ or ‘bisexual*’ or ‘queer*’ or ‘homosexual*’ or ‘lgb*’ or ‘glb*’ in combination with the terms ‘physical education’ or ‘PE’ or ‘school sport’. In the German database SURF, the terms ‘Sportunterricht’ or ‘Schulsport’ or ‘Sportlehrer*’ were combined with the keywords ‘lesbisch*’ or ‘schwul*’ or ‘bisexuell*’ or ‘homosexuell*’ or ‘queer*’ or ‘lesbe*’ or ‘lgb*’. In our review, we only took into account journal articles and dissertations, whereas we deliberately excluded university papers, book chapters and anthologies to guarantee a high scientific standard of the contributions. Systematic reviews as well as conceptual papers and monographs were also excluded. Criteria for inclusion were empirical studies focusing on the PE experiences of LGB teachers that (1) methodologically follow the qualitative approach and reconstruct teachers’ perspectives, (2) were published between 1990 and 2022, (3) were published either in English or in German.

The advantage of a qualitative review lies in the possibility of condensing existing qualitative studies so that common experiences can be reconstructed, which are then no longer permeated by individual cases and dependent on the interpretative ability of single researchers. However, there is a risk of misinterpreting other peoples’ writings or interview data that are selective and not fully available. With this in mind, it is of particular importance to interpret the data very carefully [10]. In this review, we declared and considered the interview quotes documented in the articles (primary data) as well as the interpretations of the primary authors of the studies included (secondary data) as data [55]. The consideration of primary and secondary data in the analysis appears to be advantageous and extremely valuable [54]. Firstly, it provides an alternative perspective to the authors’ interpretations. Secondly, a comparative view clarifies the extent to which the findings are context-dependent: If studies reach differing findings, these imply that institutional settings and particular contexts shape LGB teachers’ experiences of PE to a greater and more specific extent, whereas when comparing several qualitative studies, the consistencies found indicate to a certain degree that teachers’ experiences of PE (also) have aspects that are context-independent [10].

After identifying articles through the literature search, we read all included studies thoroughly and marked the relevant sections that contained ‘data’. In doing so, we distinguished between primary and secondary data. The analysis of the extracted data was based on the methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews [56]. This was conducted primarily through content analysis [57]. In the coding, which was primarily based on inductive category development [58], special attention was paid to the primary data, in which the LGB teachers discuss their perceptions, and to the secondary data, in which the researchers reconstruct and describe the teachers’ PE experiences.

In a first step, we coded the primary and secondary data separately through initial coding. This created codes at different levels of analysis. We then put the codes extracted from the primary and secondary data in relation to each other and developed new codes through comparative analysis. In the course of this process of analysis, we partly detached ourselves from the authors’ interpretations and established new codes. These initial codes still referred exclusively to the individual studies. With regard to our study, examples of these codes include ‘self-experienced discrimination’, ‘anticipated discrimination’ and ‘observed discrimination’. In a second step, intra-study comparisons were used to develop concepts from the codes that were at a higher level of abstraction; focused coding was applied to a greater extent in this phase. These concepts can be understood as a clustering of categories; examples with regard to our study are ‘initiated homophobia’ or ‘latent homophobia’. Finally, in a third step, higher-level, superordinate categories were developed based on comparisons between the studies, the internal codes, and concepts. These categories are cross-contextual and have been assigned a higher degree of applicability. Overall, the analysis aimed at identifying recurring findings on LGB teachers’ PE experiences and, based on this, to generate findings at a higher level of abstraction [59]. In the presentation of our findings, it is possible to trace the respective level of the data, as we always indicate whether it is an interview sequence from a study, the interpretation by the study authors or our own interpretation based on our analysis.

4. Results

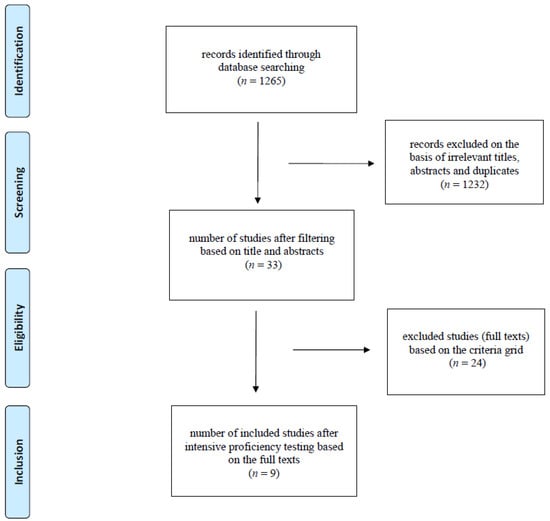

Through the systematic literature search in the selected databases in accordance with PRISMA, we identified a total of 1265 studies that met our search criteria (see Figure 1). In a first selection, we removed all duplicate records before we screened the titles and the abstracts of the articles. This resulted in the exclusion of n = 1232 studies. The remaining n = 33 articles were read and assessed for eligibility, adhering strictly to the inclusion and exclusion criteria [60]. In the end, a total of nine studies [19,40,61,62,63,64,65,66,67] were identified that met all inclusion criteria. One ethnographic fiction [68] was excluded after an intensive check for eligibility and two studies were excluded [69,70], as they only slightly exceeded the findings of the authors’ studies included in the review [61,64,65].

Figure 1.

Study selection according to PRISMA [51].

Table 1 provides an overview of the nine studies and their year of publication, country, study objective, data collection, size of the inspection group as well as the sexuality, gender and age of the inspection group. We analyzed the methodological quality of each of the articles obtained by applying the “Critical Appraisal Skills Program” (CASP) [71] and concluded that all studies included in our review met the methodological quality standards. No study from the German-speaking countries could be identified. Most of the studies originated from the United Kingdom. It is striking that the majority of the studies (n = 6) were published in the 1990s and only two studies were published after 2016.

Table 1.

Listing of the included studies.

Through the comparative analysis of the extracted data, three superordinate categories were developed, which primarily focused on the subjective experiences of LGB teachers in PE. The three categories arose from our analysis of the primary and secondary data, and do not ‘only’ reflect the interpretations of the authors of the primary studies. Accordingly, the following categories are to be understood as overarching results of our analysis, although there are some overlaps with the terms chosen by the authors of the primary studies.

On an overarching level, our analysis shows that the identified studies predominantly focused on the challenges and problems associated with the sexuality of LGB teachers. Only in one study [66], an outed lesbian PE teacher reported that her sexuality did not cause any problems. However, this case seems to be rather an exception. Overall, our analysis shows that the PE teachers interviewed in the studies perceive and anticipate school as a homophobic context (4.1). From the teachers’ perspective, PE is a special subject that they experience as particularly risky due to their sexuality (4.2). Against the backdrop of these experiences, many PE teachers use protective strategies, which mainly consist of hiding their own sexuality and ignoring the perceived homophobia (4.3). The different categories are described in detail below and our findings are reinforced using primary and secondary data.

4.1. Experiencing and Anticipating School as a Homophobic Context

Considering all the studies included in this review, school can be described as a homophobic context: Both current and earlier studies report incidents of homophobia and bullying experienced by LGB PE teachers. Over time, there seems to have been only a shift from the direct and explicit discrimination of the past to a greater degree of implicit discrimination. Accordingly, teachers interviewed in the 1990s’ studies partly faced personal hostility from students:

“The terrorising all sort of came with dyke and lessie PE teacher and I thought these people actually hate me and for nothing more than my sexuality or my job”.[61]

“I used to get telephone calls at all hours of the night, and they were kids on the phone calling me up. It wasn’t one call a night. It sometimes was three or four, and sometimes it was like 12 and 1 o’clock. I could never figure out which one it was. ‘Oh, do you want to come over and sleep with me?’ Things like this. They’d hang up, and they’d call again. I went so far as to have the telephone number changed”.[66]

The fact that, in addition to students, colleagues and school administrators are also named as perpetrators indicates that homophobia is strongly anchored in the school system and is experienced by LGB teachers in everyday life:

“The principal walked out of his office into the front office, and [the secretary] asked the principal, ‘Is Mona,’ and quick as a wink, right out of his mouth, [the principal said], ‘A lesbian.’ I felt like I had been kicked in the stomach. The English teacher’s mouth just kind of dropped open, and there was a pregnant pause, and I just said, ‘Not nice.’ And I left. Because I could feel the color come up …I never forgave him for that”.[66]

However, in the more recent studies, less personal hostility and discriminatory practices are described; in fact, the teachers speak of a homophobic school climate: “The climate was not conducive for queer sexualities (…) my administration was highly oppressive toward queer teachers” [40]. Thus, with regard to the studies, it can be seen that homophobia is not only manifested on an interpersonal level by students and teaching staff, but also on an organizational level. Overall, the school context as a whole is experienced by many teachers as homophobic.

In some cases, however, it becomes apparent that the teachers do not refer to experiences in their narratives, but rather anticipate homophobia and bullying, so that we can speak of expected reactions: “I’m assuming here, I’m probably wrong in saying this; they [parents] probably would have a negative image of me if they knew that I was gay and they would be afraid to let their kids come into my lessons” [19]. These expected negative reactions are primarily based on experiences made in other contexts as well as on the perceived homophobic society in general. Accordingly, we can speak both of experienced and anticipated homophobia in the context of school.

4.2. Experiencing PE as a Particularly Risky Subject

Especially due to its pronounced reference to the body, PE differs from other subjects: within PE, the students’ bodies are inevitably at the center of the action, as they are visibly presented, touched and commented on by teachers and classmates [8,12]. In addition, some of the teachers interviewed in the studies refer to the special nature of PE due to its body-centeredness and describe that PE teachers therefore find themselves in a special situation: “It is different for PE teachers because you are involved with the physical side of things. It has got to be worse, it’s not like you teach English or you teach Humanities” [61].

The involvement “with the physical side of things” within PE is causal for teachers’ overall perception of PE as a particularly high-risk subject: The body-centeredness of PE implies that student–teacher interactions sometimes allow for greater physical closeness than in other subjects, i.e., in the context of PE, an otherwise existing physical distance between students and teachers often disappears. This in turn seems to trigger feelings of discomfort among many LGB PE teachers—even in the context of situations where students themselves initiate physical proximity with teachers. A lesbian teacher talks about this: “[The girls are] real touchy. And this one kid will come up and put her arm around me and start walking out down the hall with me. And I get real nervous when they do stuff like that” [66]. The feelings of discomfort are also triggered by another special feature of PE: changing clothes before class and showering afterwards. In this intimate situation, too, the teachers have a supervisory function, which is perceived as uncomfortable by the majority of the interviewees. Thereby, the teachers themselves relate the feeling of discomfort to their sexuality:

“[I] hate supervising the kids going in the showers. I mean it’s just really stupid but you just feel really awkward about it”.[61]

“You know, check kids through the showers. I think because I am gay you become hypersensitive that you’re not having a good old stare just in case somebody picks up on it and that would be embarrassing to you”.[63]

In the interviews, the teachers mention the deliberate avoidance of wandering glances as well as the conscious maintenance of physical distance. Since the latter is only possible to a limited extent in the context of PE, the teachers attach great importance to keeping physical contact to a minimum—even when assistance is needed in the performance of a movement:

“All through my teaching I was very careful not to touch kids. I’m still very careful touching kids. It’s just a hang up I have because of being a lesbian touching girls. I’m just very leery of it”.[66]

In addition to discomfort during supervision in the changing room as well as when there is too little physical distance, individual conversations with students, which are part of everyday school life, also cause discomfort for many LGB teachers. Accordingly, most teachers avoid situations that could potentially make them vulnerable to attack: “So I always had the doors wide open. I always made sure there were about five kids in the trainer’s room. I was real paranoid” [67].

Although maintaining a minimum level of physical distance should also be important for many heterosexual PE teachers, our analysis shows that the interviewed teachers themselves categorize their sexuality as significant in this context. Being aware of the potential ambiguity of such sensitive situations, they want to counteract any appearance of potentially sexualized behavior through emphatically distanced behavior. Nevertheless, PE remains a subject that LGB teachers experience as particularly risky.

4.3. The Use of Protection Strategies

Taking into account the included studies, the overarching theme that emerges are protective strategies used by the teachers, which on the one hand aim to minimize potentially problem-causing situations and on the other hand to protect themselves from homophobia they expect. One of these protective strategies is the concealment and denial of one’s own sexuality. In seven of the nine studies, the deliberate concealment of one’s own sexuality from students, their parents and colleagues is described. The following interview sequence is exemplary:

“There’s nothing that I keep hidden from my kids except my real personal life… I have no intentions of my kids knowing that I’m gay”[67]

The background of the need to conceal one’s own sexuality from the students, their parents and also the teaching staff is typically justified by the teachers’ fear and anticipated negative reactions: “Scared about the kids, scared about the parents, scared about the impression it makes of yourself, scared about their judgement, their comments, their opinions and their sweeping statements they will make” [19]. However, some studies also point out that from teachers’ perspective coming out would result in losing one’s job as a teacher: “If anybody finds out I’m queer, I’m fired” [40]. Considering the fact that this study was conducted in the USA only five years ago, it can be concluded that homophobia among the school’s staff is still present in Western school systems and that homophobia determines the decision not to reveal one’s sexuality.

A frequently used concealment strategy is the avoidance of personal conversations with colleagues and students, but sometimes also deliberate deception: “My girlfriend’s name is Shauna (pseudonym) and therefore I always call her Shaun, so I’ve shortened the name so it’s a man’s name” [19]. The deliberate deception can be interpreted as ‘staged’ heterosexuality on the part of the LGB teachers, which also takes place through the outer appearance, including the choice of clothes: “Attire. I was always digging deep to try to find something. You could count on one hand the number of skirts and dresses that are hanging up in my closet” [66]. The concealment of sexuality is experienced by many not only as a burden, but also as a strong restriction: “I feel limited in my job only because so many parents look down upon it [homosexuality] still” [65].

The concealment of one’s own sexuality is described by the teachers themselves as a lie (“I’m living a lie” [61]), which often results in negative emotional states, such as feelings of self-denial and shame: “I always felt that they [colleagues] knew that I was lying or holding something back. I just felt very embarrassed about it all… I don’t think people are stupid” [63]. Concealing one’s sexuality from pupils also often seems to be unsuccessful, which in turn leads to additional emotional stress: “I would almost guarantee that every single kid, if they don’t know they must suspect that I’m a dyke because I see them look“ [65].

With regard to those interviewed in the studies, it can be stated that most do not disclose their sexuality to colleagues and students, thus deliberately creating the impression of being heterosexual. In that sense, the teachers can be described as pseudo-heterosexuals within the school. Therefore, the covering of one’s sexuality and the accompanying separation between their professional and private life seems to take a heavy emotional toll on them [62]. On a deeper level of interpretation, the concealment of one’s own sexuality can, on the one hand, be traced back to the heteronormative worldview that, in the view of the interviewed teachers, is shared by students, their parents and colleagues. On the other hand, the concealment of one’s sexuality can be traced back to perceived and anticipated homophobia, i.e., the concealment is not always the result of experienced homophobia, but also of expected homophobia (see detailed Section 4.1).

Another protective strategy that many teachers use is to deliberately ignore homophobia. In many cases, however, homophobic behavior or comments by students and colleagues are not directed at the teachers themselves, but at students or even LGB people in general. In his autoethnography, for example, Landi [40] reflects on a conversation with a colleague (Bart) about a student (Geraldo) and describes in detail his self-experienced emotional reaction:

“When Bart [colleague] called Geraldo [student] a ‘fag’, my body went through incorporeal transformations. His words led to an emotionally spiked state of fear and anger. This state affected the physical composition of my body: my face and head filled with blood and my body was suddenly battling itself (blood pressure rising, nausea, etc.)”.[40]

Beyond the uncontrollable emotional reaction described here, there is no active reaction to the colleague’s homophobic comment. Thus, the colleague’s statement remains uncommented on by the gay teacher. Likewise, an interviewed lesbian teacher does not react to a depersonalized homophobic statement of a colleague who talks about her holiday: “She [colleague] was like, ‘We went to Key West. We didn’t like the place, there were gay people everywhere. I don’t know why, it was just horrible’” [62].

Many of the LGB teachers interviewed openly admit that homophobic comments are generally ignored, even if they are directly perceived in PE class. One teacher, for example, reports systematic bullying towards a student who is perceived as gay and at the same time refers to her bad conscience that comes with ignoring the bullying: “They [classmates] don’t want to be near him. They don’t want to have to touch him. I feel badly. I’m so professional in other approaches, and I’ve just kind of closed my eyes and turned my head to this” [66].

Reasons for ignoring homophobic comments could be that LGB teachers do not want to attract attention with their behavior and do not want to endanger their heterosexual façade. Finally, addressing or criticizing homophobia could put them in a position of justification or positioning regarding their own sexuality. Against this background, this behavior can be described as a protective strategy used by the majority of teachers interviewed in the studies.

5. Discussion

Our research aimed at identifying and reviewing qualitative studies on PE from the perspective of LGB teachers. We analyzed and compared the previous findings of studies published since 1990 with the aim of presenting superordinate conclusions. A total of nine studies from four different Western countries were identified that met our inclusion criteria. However, no study from the German-speaking countries could be identified. In this respect, we can speak of a research gap with regard to the German-speaking countries, such as Germany, Austria and Switzerland. It can be assumed that the social acceptance of LGB people differs depending on the region, among other things due to country-specific political principles regarding equality (in Germany: “General Equal Treatment Act”). This may also be reflected in the PE experiences of LGB teachers. Against this background, current research from German-speaking countries seems urgently needed. Finally, it should not be assumed that the findings elaborated in this review can simply be transferred to the German context.

Looking at the studies included in this review, it becomes apparent that LGB PE teachers are regularly confronted with emotionally stressful situations at school in general and in PE lessons in particular. These include homophobia and exclusion, which are reported not only in the older studies from the 1990s but also in the more recent ones. In particular, role-related ‘border crossings’ within everyday teaching practices prove to be problematic, in which the usual institutionally prescribed professional distance between teachers and students is affected or sometimes even exceeded, among other things because teachers sometimes fear being perceived as acting sexually by students, their parents or colleagues. Our research shows that LGB teachers anticipate homophobic reactions regardless of the ‘actual’ behavior they experience from other people, which creates considerable stress for them. Woods [72] describes this form of “internalized homophobia” as “self-blame and self-hatred”, which indicates that LGB teachers themselves have internalized a negative image of LGB. This results in problems of self-acceptance as well as the fact that teachers see part of the responsibility for the (potential) reaction of others in themselves and adapt their actions accordingly, e.g., by concealing their sexuality [63]. The everyday concealment of one’s own sexuality in the professional context is seen by most teachers as a shameful self-denial, so that they have the feeling that they cannot ‘be themselves’ at school and fail to be a role model for queer students.

Similarities to the experiences of queer students in PE can be seen in the fact that problematic situations also arise for teachers due to the subject-specific focus on the body [9] as well as the heteronormative structure of the subject [6]; thus, among others, not only for queer students [10,11,13,20], but also for LGB teachers, the physical proximity and gender-differentiating locker room or shower situations inherent in PE turn into a problem. There is substantial evidence to show that PE has historically been discriminatory for LGBTQ+ people. Several studies show that discrimination and exclusion of LGBTQ+ people occurs in various sports (e.g., [41,73]). This is problematic, among other things, against the background that experiences of homophobia and sexual discrimination can have a negative impact on mental health [74].

From a research perspective, a comparative look at the experiences of queer students and teachers in future studies appears to be knowledge enriching, which could offer deeper insights into heteronormative role relations in PE. Comparative perspectives of the experiences of LGBTQ+ teachers also appear to be knowledge enhancing: the studies we included—with one exception [64]—focus on lesbian or gay teachers and thus do not take group-specific differences of LGB into account. Due to the rather one-sided findings on the experiences of lesbian teachers, we were not able to identify any differences within our review. We also cannot make any group-specific statements about the possibly unique experiences of bisexual teachers. Accordingly, there is a lack of research on the PE experiences of bisexual teachers, just as there is a lack of research regarding bisexual students [10].

Overall, our study shows many links to other discourses in PE teacher research, such as job satisfaction, patterns of stress and coping or the psychosocial health of PE teachers. In the future, these discourses should increasingly include the aspect of teacher heterogeneity. In this context, intersections of inequality dimensions, such as age and gender, should also be considered. The stronger consideration of intersectionality within research on LGB PE teachers also represents an important research perspective.

The present study has strengths and limitations. A strength is that we have taken into account PE experiences of LGB teachers who not only work(ed) in very different schools, but even in different Western school systems. Therefore, our findings can be described as cross-contextual. Moreover, the total sample of our review includes 48 LGB teachers from four different countries. This study group, which is relatively large for a qualitative study, makes it possible in a unique way to identify more general trends beyond the specifics of the individual case. However, six of the nine studies included in this review were conducted between the 1990s and 2000s. Due to social changes—especially with regard to the acceptance of LGB people in Western societies—it remains unclear to what extent these findings can still claim validity today. However, the two studies included in the review [19,40], published in 2016 and 2018, respectively, indicate that the sexuality of PE teachers still affects the experience of PE. Further, recent studies could shed light on this matter and seem necessary.

6. Conclusions

The appeal that emerges from our research is first and foremost to reflect on the precarious situation of LGB teachers, which our findings indicate, both subject specifically and in society as a whole. As a first step, we believe it is necessary to make school stakeholders (staff, headmasters, students) aware of the situation of LGB teachers. The overarching goal should be to combat existing homophobia in schools and to both protect and strengthen LGB teachers in their professional and private situation. In a wider sense, the aim should also be to create a willingness among LGB teachers to use their (pedagogical) influence for the benefit and protection of other minorities, in order to contribute to society’s acceptance and appreciation of diversity. The first step in achieving this goal is an open and visible exchange about the topic of sexual diversity in schools, which is characterized by honesty and directness, and not by making it taboo.

In our opinion, scientific findings on the PE experiences from the perspective of LGB teachers should necessarily be included in the (methodological–didactic) discussion on inclusion and diversity in general or, more specifically, sexual and gender diversity in school and in PE [1,2,3,4], which currently focuses almost exclusively on LGBTQ+ students [7,35]. As a first step, it should be recognized that LGB teachers are a ‘natural’ part of diversity in schools. In this regard, LGB teachers could play a significant role in breaking down heteronormative structures in PE [40]; especially as numerous studies indicate that heteronormative structures of PE are also caused by teachers [6,12,75]. In this sense, LGB teachers could act as experts who can critically reflect and actively interrupt the dominant heteronormative discourse [61]. However, this requires teachers to be open about their own sexuality, which, in view of our findings, typically does not seem to be the case. They could act as emphatic discussion partners and advisors or open and self-confident role models for LGB students and thus play a decisive role in their (sexuality-related) identity development. This special potential should be increasingly targeted in approaches to diversity-sensitive/inclusive teaching and in initial concepts of “queer” education in PE [40,76], which address alternative views in the context of gender, sexuality and body in PE.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.; methodology and formal analysis, J.M. and N.B.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M. and N.B.; writing—review and editing, J.M. and N.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study is based on a secondary analysis of an existing, anonymized dataset available in the primary studies included in this review. Therefore, ethical review and approval is not required.

Informed Consent Statement

Participation in the primary studies was voluntary. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the studies by the authors of the primary studies.

Data Availability Statement

The extracted interview data are available in the primary studies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Marraccini, M.E.; Ingram, K.M.; Naser, S.C.; Grapin, S.L.; Toole, E.N.; Conor O’Neill, J.; Chin, A.J.; Martinez, R.R.; Griffin, D. The roles of school in supporting LGBTQ+ youth: A systematic review and ecological framework for understanding risk for suicide-related thoughts and behaviors. J. Sch. Psychol. 2022, 91, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlile, A. Teacher Experiences of LGBTQ- inclusive Education in Primary Schools serving Faith Communities in England, UK. Pedagogy Cult. Soc. 2020, 28, 625–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naser, S.C.; Clonan-Roy, K.; Fuller, K.A.; Goncy, E.A.; Wolf, N. Exploring the experiences and responses of LGBTQ+ adolescents to school-based sexuality education. Psychol. Sch. 2022, 59, 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, M.A.; Hall, J.J. ‘This feels like a whole new thing’: A case study of a new LGBTQ-affirming school and its role in developing ‘inclusions’. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2018, 22, 1320–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, R.W.S.; Colvin, S.; Onufer, L.R.; Arnold, G.; Akiva, T.; D’Ambrogi, E.; Davis, V. Training pre-service teachers to be better serve LGBTQ high school students. J. Educ. Teach. 2021, 47, 234–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piedra, J.; Ramírez-Macías, G.; Ries, F.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, A.R.; Phipps, C. Homophobia and Heterosexism: Spanish Physical Education Teachers’ Perspectives. Sport Soc. 2016, 19, 1156–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, D.; Flory, S.B.; Safron, C.; Marttinen, R. LGBTQ Research in Physical Education: A rising Tide? Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2020, 25, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paechter, C. Changing School Subjects: Power, Gender and Curriculum; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ruin, S.; Meier, S. Body and Performance in (Inclusive) PE Settings. An Examination of Teacher Attitudes. Int. J. Phys. Educ. 2017, 54, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.; Böhlke, N. Physical Education from LGBTQ+ Students’ Perspective. A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, D. LGBTQ Youth, Physical Education, and Sexuality Education: Affect, Curriculum, and (New) Materialism. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Devís-Devís, J.; Pereira-García, S.; López-Cañada, E.; Pérez-Samaniego, V.; Fuentes-Miguel, J. Looking back into Trans Persons’ Experiences in heteronormative secondary Physical Education Contexts. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2018, 23, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenspan, S.B.; Griffith, C.; Hayes, C.R.; Murtagh, E.F. LGBTQ + and Ally Youths’ School Athletics Perspectives: A Mixed-Method Analysis. J. LGBT Youth 2019, 16, 403–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Miguel, J.; Pérez-Samaniego, V.; López-Cañada, E.; Pereira-García, S.; Devís-Devís, J. From Inclusion to Queer-Trans Pedagogy in School and Physical Education: A Narrative Ethnography of Trans Generosity. Sport Educ Soc. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, P.; Lahelma, E. The Gendering Processes in the Field of Physical Education. Gend. Educ. 2010, 22, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gieß-Stüber, P.; Sobiech, G. Zur Persistenz geschlechtsbezogener Differenzsetzungen im Sportunterricht. In Sport & Gender—(Inter-)nationale Sportsoziologische Geschlechterforschung. Theoretische Ansätze, Praktiken und Perspektiven; Sobiech, G., Günter, S., Eds.; VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2017; pp. 265–280. [Google Scholar]

- Wagenknecht, P. Was ist Heteronormativität? Zur Geschichte und Gehalt des Begriffs. In Heteronormativität. Empirische Studien zu Geschlecht, Sexualität und Macht; Hartmann, J., Klesse, C., Wagenknecht, P., Fritzsche, B., Hackmann, K., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2007; pp. 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, G. Challenging Heterosexism, Homophobia and Trans-phobia in Physical Education. In Equity and Inclusion in Physical Education and Sport; Stidder, G., Hayes, H., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 107–121. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, L.L.; Brown, D.H.K.; Smith, L. We Are Getting There Slowly: Lesbian Teacher Experiences in the Post-Section 28 Environment. Sport Eudc. Soc. 2016, 21, 299–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrick, S.S.C.; Duncan, L.R. A systematic scoping review of physical education experiences from the perspective of LGBTQ+ students. Sport Educ. Soc. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miethling, W.-D. Sportlehrer*innenforschung. In Empirie des Schulsports; Balz, E., Bräutigam, M., Miethling, W.-D., Wolters, P., Eds.; Meyer & Meyer: Aachen, Germany, 2020; pp. 174–216. [Google Scholar]

- Chróinín, D.N.; O’Sullivan, M. Elementary classroom teachers’ beliefs across time: Learning to teach physical education. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2016, 35, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åsebø, E.K.S.; Løvoll, H.S. Exploring coping strategies in physical education. A qualitative case study. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvoy, E.; Heikinaro-Johansson, P.; MacPhail, A. Physical education teacher educators’ views regarding the purpose(s) of school physical education. Sport Educ. Soc. 2017, 22, 812–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eirín-Nemiña, R.; Sanmiguel-Rodríguez, A.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, J. Professional satisfaction of physical education teachers. Sport Educ. Soc. 2022, 27, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorjussen, I.M.; Sisjord, M.K. Students’ physical education experiences in a multi-ethnic class. Sport Educ. Soc. 2018, 23, 694–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocock, T.; Miyahara, M. Inclusion of students with disability in physical education: A qualitative meta-analysis. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2018, 22, 751–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, I.; Bartsch, F.; Rulofs, B. Unterschiede zwischen Schüler*innen im Sportunterricht in der Wahrnehmung von Lehrkräften—Entwurf einer Strukturierung auf Basis einer quantitativen Befragung von Sportlehrkräften. Ger. J. Exerc. Sport Res. 2021, 51, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frohn, J.; Pfitzner, M. Heterogenität. Sportpädagogik 2011, 35, 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, T.; Ní Chróinín, D. Pedagogical principles that support the prioritisation of meaningful experiences in physical education: Conceptual and practical considerations. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2022, 27, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parri, M.; Ceciliani, A. Best practice in P.E. for gender equity—A review. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2019, 19, 1943–1952. [Google Scholar]

- Penney, D. Gender and Physical Education: Contemporary Issues and Future Directions; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Firley-Lorenz, M. Gender im Sportlehrberuf. Sozialisation und Berufstätigkeit von Sportlehrerinnen in der Schule; Butzbach/Griedel: Afra, Iran, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Vilanova, A.; Mateu, P.; Gil-Quintana, J.; Hinojosa-Alcalde, I.; Hartmann-Tews, I. Facing Hegemonic Masculine Structures: Experiences of Gay Men studying Physical Activity and Sport Science in Spain. Sport Educ. Soc. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, P.; Kokkonen, M. Heteronormativity meets Queering in Physical Education: The Views of PE Teachers and LGBTIQ+ Students. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2021, 27, 368–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crothers, L.M.; Kolbert, J.B.; Berbary, C.; Chatlos, S.; Lattanzio, L.; Tiberi, A.; Wells, D.S.; Bundick, M.J.; Lipinski, J.; Meidl, C. Teachers‘, LGBTQ Students‘, and Student Allies‘ Perceptions of Bullying of sexually-diverse Youth. J. Aggress Maltreatment Trauma 2017, 47, 972–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosciw, J.G.; Greytak, E.; Zongrone, A.; Clark, C.M.; Truong, N.L. The 2017 National School Climate Survey: The Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Youth in Our Nation’s Schools; GLSEN: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Steeg, E.; Schipper-Van Veldhoven, N.; Cense, M.; Bellemans, T.; de Martelaer, K. A Dutch perspective on sexual integrity in sport contexts: Definition and meaning for practice. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2021, 26, 460–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, H.; Fagrell, B.; Redelius, K. Queering Physical Education. Between Benevolence towards Girls and a Tribute to Masculinity. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2009, 14, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, D. Toward a Queer Inclusive Physical Education. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2018, 23, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann-Tews, I.; Menzel, T.; Braumüller, B. Experiences of LGBTQ+ individuals in sports in Germany. Ger J. Exerc. Sport Res. 2021, 52, 39–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweer, M.K.W. Sexismus und Homophobie im Sport. Interdisziplinäre Perspektiven auf ein vernachlässigtes Forschungsfeld; VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, C. School’s Out: Gay and Lesbian Teachers in the Classroom; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ferfolja, T. State of the Field Review: Stories So Far: An Overview of the Research on Lesbian Teachers. Sexualities 2009, 12, 378–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferfolja, T.; Hopkins, L. The Complexities of Workplace Experience for Lesbian and Gay Teachers. Crit. Stud. Educ. 2013, 54, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, E.M. Coming out as a Lesbian, Gay or Bisexual Teacher: Negotiating Private and Professional Worlds. Sex. Educ. 2013, 13, 702–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, E.; Harris, H.; Jones, T. Australian LGBTQ teachers, exclusionary spaces and points of interruption. Sexualities 2016, 19, 286–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, P. Lesbian and gay educators: Opening the classroom closet. Empathy 1992, 3, 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Llewellyn, A.; Reynolds, K. Within and between heteronormativity and diversity: Narratives of LGB teachers and coming and being out in schools. Sex. Educ. 2021, 21, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llewellyn, A. Bursting the ‘childhood bubble’: Reframing discourses of LGBTQ+ teachers and their students. Sport Educ. Soc. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred Reporting Items for systematic Review and meta-analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 Statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, B.L.; Thorne, S.E.; Canam, C.; Jillings, C. Meta-Study of Qualitative Health Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M.L. Application of systematic Review Methods to qualitative Research: Practical Issues. J. Adv. Nurs. 2004, 48, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, A.; Copnell, B. A Guide to Writing a Qualitative Systematic Review Protocol to Enhance Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing and Health Care. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2016, 13, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toye, F.; Seers, K.; Allcock, N.; Briggs, M.; Carr, E.; Barker, K. Meta-Ethnography 25 Years on: Challenges and Insights for Synthesising a large Number of Qualitative Studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Harden, A. Methods for the thematic Synthesis of Qualitative Research in Systematic Reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon-Woods, M.; Agarwal, S.; Jones, D.; Young, B.; Sutton, A. Synthesizing qualitative and quantitative evidence: A review of possible methods. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2005, 10, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Content Analysis. Forum Qual. Soz./Forum Qual Soc. Res. 2000, 1, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Munn, Z.; Tufanaru, C.; Aromataris, E. Data Extraction and Synthesis: The Steps Following Study Selection in a Systematic Review. Am. J. Nurs. 2014, 114, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popay, J.; Rogers, A.; Williams, G. Rationale and Standards for the Systematic Review of qualitative Literature in Health Services Research. Qual. Health Res. 1998, 8, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, G. Conforming and Contesting with (a) Difference: How Lesbian Students and Teachers Manage Their Identities. Int. Stud. Sociol. Educ. 1996, 6, 191–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparkes, A.C. Self, Silence and Invisibility as a Beginning Teacher: A Life History of Lesbian Experience. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 1994, 15, 93–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squires, S.L.; Sparkes, A.C. Circles of Silence: Sexual Identity in Physical Education and Sport. Sport Educ. Soc. 1996, 1, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykes, H. The Angel’s Playground: Same-Sex Desires of Physical Education Teachers. J. Gay Lesbian Soc. Serv. 2003, 1, 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykes, H. Teaching Bodies, Learning Desires: Feminist-Poststructural Life Histories of Heterosexual and Lesbian Physical Education Teachers in Western Canada; University of British Columbia: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, S.E. The Contextual Realities of Being a Lesbian Physical Education Teacher: Living in Two Worlds. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Amherst, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, S.E.; Harbeck, K.M. Living in Two Worlds: The Identity Management Strategies Used by Lesbian Physical Educators. J. Homosex. 1992, 22, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sparkes, A.C. Ethnographic Fiction and Representing the Absent Other. Sport Educ. Soc. 1997, 2, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, G. Queering the Pitch and Coming Out to Play: Lesbians in Physical Education and Sport. Sport Educ. Soc. 1998, 3, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykes, H. Pedagogies of Censorship, Injury, and Masochism: Teacher Responses to Homophobic Speech in Physical Education. J. Curric. Stud. 2004, 36, 75–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist. 2018. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/images/checklist/documents/CASP-Qualitative-Studies-Checklist/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2023).

- Woods, S.E. Describing the experience of lesbian physical educators: A phemomenological study. In Research in Physical Education and Sport: Exploring Alternative Visions; Sparkes, A., Ed.; Falmer Press: London, UK, 1992; pp. 90–117. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, J.; Delto, H.; Böhlke, N.; Mutz, M. Sports Activity Levels of Sexual Minority Groups in Germany. Sexualities 2022, 3, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostwick, W.B.; Boyd, C.J.; Hughes, T.L.; West, B.T.; McCabe, S.E. Discrimination and mental health among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2014, 84, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, H.; Redelius, K.; Fagrell, B. Moving (in) the Heterosexual Matrix. On Heteronormativity in Secondary School Physical Education. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2011, 16, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, H.; Quennerstedt, M.; Öhman, M. Heterotopias in Physical Education: Towards a Queer Pedagogy? Gend. Educ. 2014, 26, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).