Sports Activity Levels of Sexual Minority Groups in Germany

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Frequency of Participation in Sports Activities

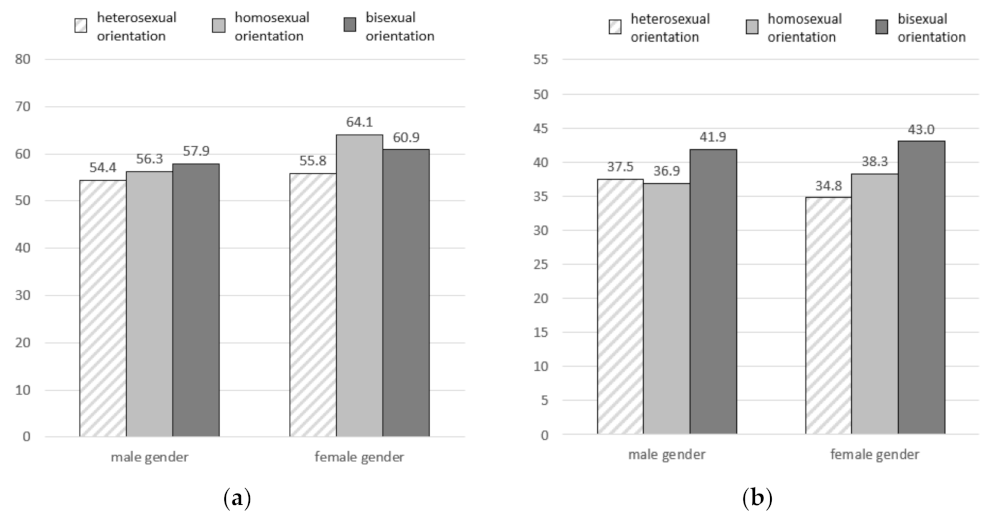

3.2. Amount of Time Spent with Physical Activities

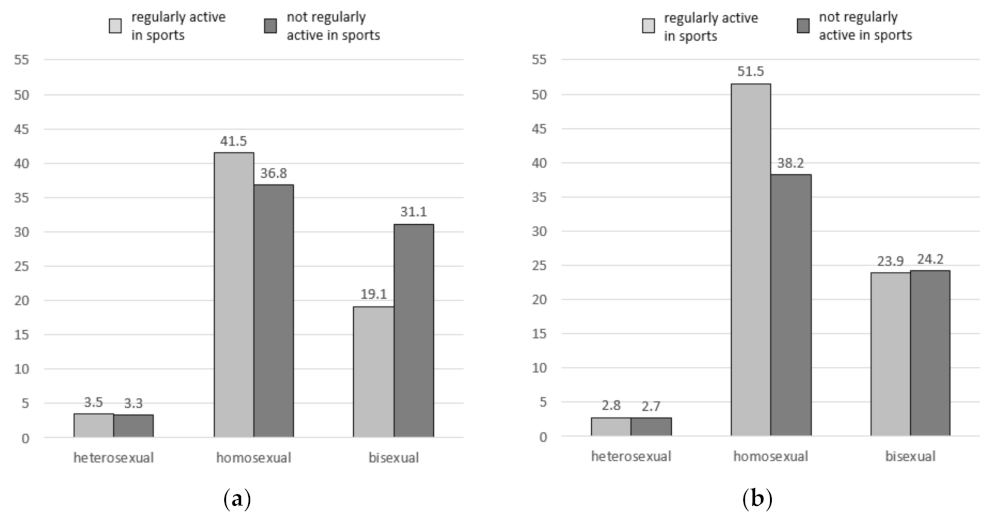

3.3. Sexual Discrimination and Sports Activities

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rhodes, R.E.; Janssen, I.; Bredin, S.S.D.; Warburton, D.E.R.; Bauman, A. Physical activity: Health impact, prevalence, correlates and interventions. Psychol. Health 2017, 32, 942–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warburton, D.E.R.; Bredin, S.S.D. Health benefits of physical activity: A systematic review of current systematic reviews. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2017, 32, 541–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sattelmair, J.; Pertman, J.; Ding, E.L.; Kohl, H.W.; Haskell, W.; Lee, I.-M. Dose response between physical activity and risk of coronary heart disease. Circulation 2011, 124, 789–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mutz, M.; Reimers, A.K.; Demetriou, Y. Leisure time sports activities and life satisfaction: Deeper insights based on a representative survey from Germany. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2020, 16, 2155–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, W. A systematic review of the relationship between physical activity and happiness. J. Happiness Stud. 2019, 20, 1305–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Omar, K.; Messing, S.; Sarshar, M.; Gelius, P.; Ferschl, S.; Finger, J.; Baumann, A. Sociodemographic correlates of physical activity and sport among adults in Germany: 1997–2018. Ger. J. Exerc. Sport Res. 2021, 51, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutz, M.; Müller, J. Social stratification of leisure time sport and exercise activities: Comparison of ten popular sports activities. Leis. Stud. 2021, 40, 597–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenspan, S.; Griffith, C.; Watson, R. LGBTQ+ youth’s experiences and engagement in physical activity: A comprehensive content analysis. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2019, 4, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, D. Sportophobia. Why do some men avoid sport? J. Sport Soc. Issues 2006, 30, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargie, O.; Mitchell, D.; Somerville, I. ‘People have a knack of making you feel excluded if they catch on to your difference’: Transgender experiences of exclusion in sport. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2017, 52, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Doull, M.; Watson, R.J.; Smith, A.; Homma, Y.; Saewyc, E. Are we leveling the playing field? Trends in sports participation among sexual minority youth. J. Sport Health Sci. 2018, 7, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kulick, A.; Wernick, L.J.; Espinoza, M.A.V.; Newman, T.J.; Dessel, A.B. Three strikes and you’re out: Culture, facilities, and participation among LGBTQ youth in sports. Sport Educ. Soc. 2019, 24, 939–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mereish, E.H.; Poteat, V.P. Let´s get physical: Sexual orientation disparities in physical activity, sports involvement, and obesity among a population-based sample of adolescents. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 1842–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calzo, J.P.; Roberts, A.L.; Corliss, H.L.; Blood, E.A.; Kroshus, E.; Austin, S.B. Physical activity disparities in heterosexual and sexual minority youth ages 12-22 years old: Roles of childhood gender nonconformity and athletic self-esteem. Ann. Behav. Med. 2014, 47, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Elling, A.; Janssens, J. Sexuality as a structural principle in sport participation. Negotiating sports spaces. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2009, 44, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, L.B.; Turner, B.; Felt, D.; Marro, R.; Phillips, G.L. Risk factors for diabetes are higher among non-heterosexual US high-school students. Pediatr. Diabetes 2018, 19, 1137–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.H.; So, W.Y. Differences in lifestyles including physical activity according to sexual orientation among Korean adolescents. Iran. J. Public Health 2013, 42, 1347–1353. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rosario, M.; Corliss, H.L.; Everett, B.G.; Reisner, S.L.; Austin, S.B.; Buchting, F.O.; Birkett, M. Sexual orientation disparities in cancer-related risk behaviors of tobacco, alcohol, sexual behaviors, and diet and physical activity: Pooled youth risk behavior surveys. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipp, J. Sport and sexuality: Athletic participation by sexual minority and sexual majority adolescents in the U.S. Sex Roles 2011, 64, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavoura, A.; Kokkonen, M. What do we know about the sporting experiences of gender and sexual minority athletes and coaches? A scoping review. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2020, 14, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiocco, R.; Pistella, J.; Salvati, M.; Ioverno, S.; Lucidi, F. Sports as a risk environment: Homophobia and bullying in a sample of gay and heterosexual men. J. Gay Lesbian Ment. Health 2018, 22, 385–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Symons, C.M.; O’Sullivan, G.A.; Polman, R.C.J. The impacts of discriminatory experiences on lesbian, gay and bisexual people in sport. Ann. Leis. Res. 2016, 6, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Herrick, S.S.C.; Duncan, L.R. A qualitative exploration of LGBTQ+ and intersecting identities within physical activity contexts. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2018, 40, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scandura, C.; Braucci, O.; Bochicchio, V.; Valerio, P.; Amodeo, A.L. “Soccer is a matter of real men?” Sexist and homophobic attitudes in three Italian soccer teams differentiated by sexual orientation and gender identity. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2019, 17, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pariera, K.; Brody, E.; Scott, D.T. Now that they’re out: Experiences of college athletics teams with openly LGBTQ players. J. Homosex. 2021, 68, 733–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denison, E.; Bevan, N.; Jeanes, R. Reviewing evidence of LGBTQ+ discrimination and exclusion in sport. Sport Manag. Rev. 2020, 24, 389–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann-Tews, I.; Menzel, T.; Braumüller, B. Homo- and transnegativity in sport in Europe: Experiences of LGBT+ individuals in various sport settings. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2020, 56, 997–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denison, E.; Kitchen, A. Out on the Fields. The First International Study on Homophobia in Sport. 2015. Available online: https://outonthefields.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Out-on-the-Fields-Final-Report-1.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Demers, G. Sports Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Athletes; Laval University Press: Laval, QC, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Symons, C.; Sbaraglia, M.; Hillier, L.; Mitchell, A. Come Out to Play: The Sports Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) People in Victoria. Technical Report; Victoria University Press: Melbourne, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, E.; Bullingham, R. Openly lesbian team sport athletes in an era of decreasing homohysteria. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2015, 50, 647–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Petty, L.; Trussell, D.E. Experiences of identity development and sexual stigma for lesbian, gay, and bisexual young people in sport: “Just survive until you can be who you are”. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2018, 10, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.; Power, J.; Hill, A.O.; Despott, N.; Carman, M.; Jones, T.W.; Anderson, J.; Bourne, A. Religious conversion practices and LGBTQA + youth. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Samaniego, V.; Fuentes-Miguel, J.; Pereira-Garcia, S.; López-Cañada, E.; Devis-Devis, J. Experiences of trans persons in physical activity and sport: A qualitative meta-synthesis. Sport Manag. Rev. 2019, 22, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.; Böhlke, N. Physical education from LGBTQ+ students’ perspective. A systematic review of qualitative studies. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, D. LGBTQ Youth, Physical Education, and Sexuality Education: Affect, Curriculum, and (New) Materialism; University Press: Auckland, New Zealand, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Devís-Devís, J.; Pereira-García, S.; López-Cañada, E.; Pérez-Samaniego, V.; Fuentes-Miguel, J. Looking back into trans persons’ experiences in heteronormative secondary physical education contexts. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2018, 23, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.A.; Arcelus, J.; Bouman, W.P.; Haycraft, E. Sport and transgender people: A systematic review of the literature relating to sport participation and competitive sport policies. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Messner, M.A. When bodies are weapons: Masculinity and violence in sport. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 1990, 25, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ramaeker, J.; Petrie, T.A. “Man up!”: Exploring intersections of sport participation, masculinity, psychological distress, and help-seeking attitudes and intentions. Psychol. Men Masc. 2019, 20, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntz, A.; Davidov, E.; Schwartz, S.H.; Schmidt, P. Human values, legal regulation, and approval of homosexuality in Europe: A cross-country comparison. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 45, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Poushter, J.; Kent, N.O. The Global Divide on Homosexuality Persists, but Increasing Acceptance in Many Countries Over Past Two Decades. 2020. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2020/06/PG_2020.06.25_Global-Views-Homosexuality_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2022).

- Adams, A.; Anderson, E. Exploring the relationship between homosexuality and sport among the teammates of a small, midwestern catholic college soccer team. Sport Educ. Soc. 2012, 17, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, A.; Anderson, E.; Carr, S. The declining existence of men’s homophobia in British sport. J. Study Sports Athl. Educ. 2012, 6, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollè, L.; Cazzini, E.; Santoniccolo, F.; Trombetta, T. Homonegativity and sport: A systematic review of the literature. J. Gay Lesbian Soc. Serv. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goebel, J.; Grabka, M.M.; Liebig, S.; Kroh, M.; Richter, D.; Schröder, C.; Schupp, J. The German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP). Jahrb. Natl. Stat. 2019, 239, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Glemser, A.; Huber, S.; Rathje, M. SOEP-Core–2019: Report of Survey Methodology and Fieldwork; DIW/SOEP: Berlin, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Delto, H. Vorurteile und Stereotype im Vereinssport. Eine Analyse im Kontext von Sozialisation und Antidiskriminierung; Transcript: Bielefeld, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Menzel, T.; Braumüller, B.; Hartmann-Tews, I. The Relevance of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in Sport in Europe. Findings from the Outsport Survey; German Sport University Cologne: Cologne, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Delto, H. Homophobe Stereotype im organisierten Vereinssport. In Sexismus und Homophobie im Sport: Interdisziplinäre Perspektiven auf ein vernachlässigtes Forschungsfeld; Schweer, M., Ed.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2018; pp. 41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Delto, H. Der Sport und die Macht der Vorurteile: Eine Studie zu sozialen Einstellungen von Mitgliedern in Sportvereinen. Sport Ges. 2018, 15, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhlke, N.; Müller, J. Man muss sich nicht verstecken oder erklären. Es ist einfach unkompliziert“–Sporterfahrungen und Motivlagen von Mitgliedern eines queeren (LGBTI*) Sportvereins. Sport Ges. 2020, 17, 121–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostwick, W.B.; Boyd, C.J.; Hughes, T.L.; West, B.T.; McCabe, S.E. Discrimination and mental health among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2014, 84, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Walther-Ahrens, T. Sportlich vielfältig oder Sport ohne blöde Lesben und olle Schwuchteln. In CSR und Sportmanagement; Hildebrandt, A., Ed.; Springer Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019; pp. 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann-Tews, I.; Menzel, T.; Braumüller, B. Experiences of LGBTQ+ individuals in sports in Germany. Ger. J. Exerc. Sport Res. 2021, 52, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine, C. Female Olympians’ voices: Female sports categories and International Olympic Committee transgender guidelines. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caudwell, J. [Transgender] young men: Gendered subjectivities and the physically active body. Sport Educ. Soc. 2014, 19, 398–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Müller, J.; Delto, H.; Böhlke, N.; Mutz, M. Sports Activity Levels of Sexual Minority Groups in Germany. Sexes 2022, 3, 209-218. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes3010016

Müller J, Delto H, Böhlke N, Mutz M. Sports Activity Levels of Sexual Minority Groups in Germany. Sexes. 2022; 3(1):209-218. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes3010016

Chicago/Turabian StyleMüller, Johannes, Hannes Delto, Nicola Böhlke, and Michael Mutz. 2022. "Sports Activity Levels of Sexual Minority Groups in Germany" Sexes 3, no. 1: 209-218. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes3010016

APA StyleMüller, J., Delto, H., Böhlke, N., & Mutz, M. (2022). Sports Activity Levels of Sexual Minority Groups in Germany. Sexes, 3(1), 209-218. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes3010016