Abstract

Survival and death are the two most important things in life. The ancient Chinese people attached great importance to death, so the funeral ceremonies were very complete. Since its inception, Taoism has actively participated in funeral activities, so the combination of epitaphs and tomb inscriptions has a historical origin. The establishment of a unified dynasty in the Sui Dynasty provided an opportunity for the integration and development of Taoism in the north and south. The Mao Shanzong (茅山宗) in the southern region began to spread to the north, gradually integrating Lou Guan Dao (樓觀道) and becoming the mainstream of Northern Taoism. The epitaph of Wu Tong in the Sui Dynasty is engraved with rich Taoist symbols, and the epitaph text adopts the language content of “Zhen Gao” (真誥), which is a typical representative of the integration of Northern and Southern Taoism and reflects Taoism’s concern for death.

Taoism is a native religion in ancient China. Since its birth in the Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220), Taoism has continued through the ages, spread widely, and has many followers. At the same time as Taoism took form, Buddhism began to be introduced into Han China and developed rapidly. During the Wei-Jin (魏晉) (220–420) and Southern and Northern Dynasty (南北朝) (420–589) periods, Buddhism was favored by the imperial family but also was believed by both the upper and lower classes. As a result, a large number of Buddhist stone carvings appeared in Gansu (甘肅), Shanxi (山西), Shaanxi (陝西), Henan (河南), Sichuan (四川), and other regions. In contrast, besides the support of the court in the early Han Dynasty, Taoism seemed to be less popular in society in comparison with Buddhism. However, as an indigenous religion, Taoism has also entered the world of believers in its own way and has exerted influence in every detail of life. The ancient Chinese people paid particular attention to two major events, one is military affairs, and the other is sacrifice. In particular, people in ancient times held solemn commemorative activities for the dead. Because China’s traditional beliefs bred Taoism, Taoism plays an important role in sacrificial activities and is the dominant religion in sacrificial offerings. In this respect, Buddhism is not as active as Taoism. In medieval China, people placed an epitaph in the tomb to record the life story of the deceased. The epitaph has been used for a long time, from the pre-Qin period to the Republic of China. The number of epitaphs is also very large, totally over 60,000 epitaphs from ancient China.1 Because of their important historical value, epitaphs have played an important role in academic research. This paper intends to use the unearthed Wu Tong epitaph of the Sui Dynasty (591–618) to investigate Taoist death care in medieval China.

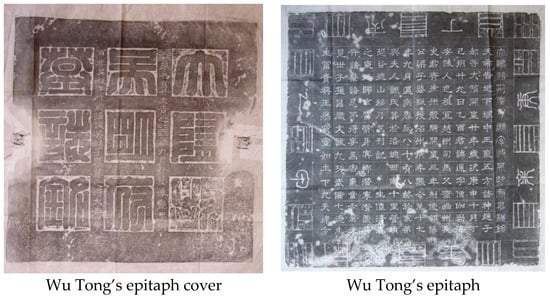

Wu Tong’s epitaph (Figure 1), the full name of which is “The Epitaph of the Late Magistrate Wu of Guangnian Country, Mingzhou Commandery, of the Great Sui” (大隋洺州廣年縣令故吳明府墓志銘), was unearthed in Luoyang (洛陽), Henan (河南) Province, in recent years (See Wang 2011). The epitaph is composed of an epitaph stone and epitaph cover. The epitaph cover is engraved with “The Epitaph of the Late Magistrate Wu of the Great Sui”. At the same time, the epitaph cover is also engraved with the symbols and characters of the Book of Changes (周易), and the content is intended to warn off tomb robbers. The epitaph records the Wu family lineage and official achievements of Wu Tong, who served as the Magistrate of Guangnian County in the Mingzhou Commandery during the early Sui Dynasty.

Figure 1.

Wu Tong’s epitaph and cover.

Below is the content of the epitaph:

【墓誌蓋】大隋故吴明府墓誌銘萃,六月卦,大吉之。

謙,九月卦。塟後壹遷八百年,吴奴子所發掘,誡吴奴子厚塟之,得大吉昌。

【誌文】大隋洺州廣年縣令故吴明府墓誌銘天帝告地下冢中王氣、五方諸神、趙子都等:大隋開皇廿年歲次庚申十月丁巳朔廿九日乙酉,君諱通,字僧伽,勃海安陵人也。祖宜,趙州司馬。父齋,幽州長史。君齊徐州散騎,開皇三年,勅使郃陽公梁子恭版授洺州廣年縣令,至十七年九月遘疾,春秋八十有八,終於家第,與夫人謝氏葬於洛城西南十里營墳。恐谷徙山移,乃為刊記。生值清真之氣,死歸玄宮。翳身冥鄉,潛寧澄虛,辟斥諸禁諸忌,不得妄為害氣,當令於後見世子孫昌熾,文詠九功,武備七德,生生富貴,興王無窮,壹如土下九天律令。[on epitaph cover] The Epitaph of the Late Magistrate Wu of the Great Sui

“Cui ( ), the divination in the sixth month is greatly auspicious. Qian (

), the divination in the sixth month is greatly auspicious. Qian ( ), was divined in the ninth month. One thousand and eight hundred years after my burial, Wu Nuzi will excavate the tomb. I warn Wu Nuzi to bury my tomb well so he will receive great fortune.”

), was divined in the ninth month. One thousand and eight hundred years after my burial, Wu Nuzi will excavate the tomb. I warn Wu Nuzi to bury my tomb well so he will receive great fortune.”

[Epitaph] The Epitaph of the Late Magistrate Wu of Guangnian County, Mingzhou Commandery, of the Great Sui:

“The Heavenly God tells the kingly Qi, gods of the five directions, Zhao Zidu, and others in the tomb under the ground2: in the twentieth year of the Kaihuang period of the great Sui, the year was gengshen, tenth moon dingsi, the day yiyou, the twenty-ninth day. Tong, styled Sengqie, was from Anling, Bohai Commandery. His grandfather was Yi, Commander of Zhao Commandery. His father Zhai was the Chief Clerk of the Youzhou Commandery. Tong was appointed as Cavalier Attendant of the Xuzhou Commandery. In the third year of Kaihuang, an imperial decree commended Liang Zigong, the Lord of Heyang, to appoint Tong the honorary title of magistrate of Guangnian, Mingzhou Commandery. Tong enjoyed this until he was struck by an illness in the ninth month of the seventeenth year of Kaihuang. He died at home, aged eighty-eight. He was buried together with his wife, Lady Xie, in the tomb ten li southwest of Luoyang. Concerned about the changes in landscape, an epitaph was carved in order to mark the tomb. When he was alive, he enjoyed the pure and true qi; after he died, he returned to the Dark Palace. His body hides in the land of the deceased; quietly he returns to the world of immortals. I drive out and banish those evil and prohibited; they should not dare to cause harm. It should from now on to witness his descendants flourish, their civil services are celebrated by the Nine Merits3, and their military duties are completed by the Seven Merits4. Each generation will be rich and noble and enjoy endless prosperity. This acts as the law and command of the underground world and the world of the nine heavens.”

Luoyang City

As can be seen in the epitaph, the tomb occupant was Wu Tong. His grandfather, Wu Yi, and his father, Wu Zhai, are not mentioned in historical records or in medieval texts. According to the epitaph, Wu Tong’s native place was Anling in the Bohai Commandery, which is now north of Wuqiao (吳橋) County, Hebei (河北)Province. Wu Tong once served as a Cavalier Attendant-in-Ordinary (sanqi changshi, 散騎常侍) in the Northern Qi (北齊) (550–577). In the third year of the Kaihuang era in the Sui Dynasty (583), Wu Tong was given the honor of the Magistrate of Guangnian County, Mingzhou Commandery. Sanqichangshi, Cavalier Attendant-in-Ordinary, was an office set up during the Three Kingdoms period (220–289), and its responsibility was remonstration. Although this office was continued by later dynasties, it was never an important post. In addition to this, Wu Tong was appointed as the magistrate by Liang Zigong, and this event can be found in the Suishu (隋書). Zhao Gui’s (趙軌) (?_?) biography in the Suishu records that Liang Zigong, a senior official, toured the empire, investigated illegal affairs, and released food for disaster relief. It was at this time that Wu Tong was granted the Magistrate of Guangnian County by Liang Zigong. The appointment was mentioned as banshou (版授), “conferring position with a blank document”, which was a system of granting official titles popular in the Northern Dynasty that aimed at honoring the elderly. According to the policy, seniors reaching a certain age should be granted an honorable title. For example, the Emperor of the Northern Zhou (北周) (557–581) announced that officials aged sixty and above, or commoners aged seventy and above, should be honored with an official title. The Sui Dynasty inherited this system, In addition to this, the Sui court also gave elders not only official titles but also food and other awards. Furthermore, the court decreed that anyone older than ninety should be given the honorific title of commandery governor and, for anyone over eighty, the title of country magistrate (See Wei 1982). According to the epitaph, Wu Tong was seventy-four years old at that time and was qualified for the magistrate title. The contents recorded in the epitaph reflect the historical reality of Sui granting honorific official titles to the elderly. The epitaph also records that Wu Tong died in the seventeenth year of the Kaihuang period (597) at the age of eighty-eight. According to this record, Wu Tong should have been born in the third year of the Yongping (永平) period in the Northern Wei Dynasty (510) and lived through the Northern Wei, the Eastern Wei (東魏) (534–550), the Northern Qi, and the Sui.

The epitaphs of the Sui and Tang dynasties, which were influenced by Taoist culture, can be divided into two categories: one is the epitaph of Taoist priests, and the other is the epitaph of people who believed in Taoism. For the study of Taoist culture, the latter has more historical value, because the epitaphs of people who believed in Taoism can reflect more the true state of popular religion and folk beliefs. However, there is only scant research and limited understanding of epitaphs with Taoist characters and symbols, which has affected the in-depth study of the connotations of Taoist culture. The epitaph of Wu Tong, which this article discusses, has a very rich Taoist cultural connotation, reflected by its external form and content. This is discussed in detail below.

First, the external form of Wu Tong’s epitaph has strong Taoist characteristics.

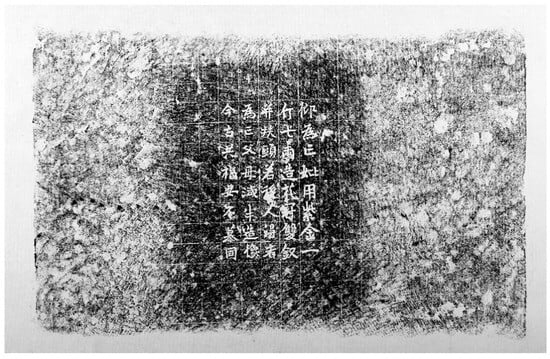

Different from other epitaphs of the time, Wu Tong’s epitaph contains forty-two Chinese characters that record two divinations performed by Wu Tong, one in the sixth month, and the other in the ninth month. Its content is to warn grave robbers to rebury the tomb properly. Such a practice has been found in ancient tombs both in China and abroad.5 There are similar cases in other ancient Chinese tombs. For example, there are words on the epitaph of Yuan Yu (元郁) (462–491) (Figure 2), King of Jiyin (濟陰) of the Northern Wei Dynasty, telling later generations to use the gold and silver found in the tomb to rebuild the tomb so that they can acquire more wealth (See Wang 2013b). However, by comparison, it is clear that the words on the epitaph of Yuan Yu are only admonitions, while those on the epitaph of Wu Tong are warnings. They are quite different from each other. What is more noteworthy is that there are hexagram symbols from the Book of Changes inscribed on Wu Tong’s epitaph. The purpose of these symbols, which are based on the Book of Changes calculation, was to warn the tomb robber who would break into the tomb one thousand and eight hundred years later. This type of warning is more powerful than the admonishment found in Yuan Yu’s tomb. It is well known that Laozi, the founder of Taoism, studied the theory of Yin and Yang, and the Book of Changes also emphasizes the Yin and Yang theory. Later, Taoism took the Book of Changes as an important classic and important Taoist teachings evolved from the Book of Changes. Wu Tong was an expert of Book of Changes, which shows that he was a Taoist believer.

Figure 2.

Yuan Yu’s epitaph cover.

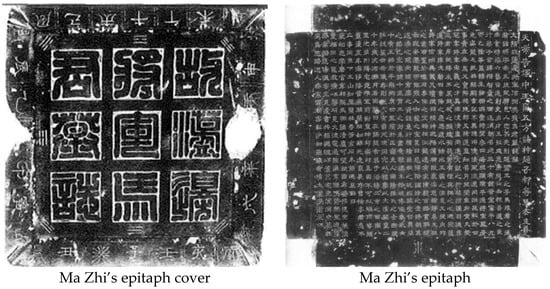

Similar to the contents of the epitaph cover, the text of Wu Tong’s epitaph is surrounded by hexagrams from the Book of Changes and ganzhi (干支) symbols on its margins. These are the same practices as inscribing Taoist symbols on cosmographic boards (shipan, 式盤) and bronze mirrors, and they all demonstrate strong Taoist cultural elements. Patterns of this type can also be seen in the epitaph of Ma Zhi (馬穉) (524–600) (Figure 3), which was inscribed in the twentieth year of the Kaihuang period (600) (See Zhao 1995). Wu Tong’s epitaph and Ma Zhi’s epitaph were inscribed at the same time and in the same place, with similar Taoist characteristics, and both were written in the clergy style (lishu, 隸書); there is a possibility that they were written by the same author. This indicates that in the Sui Dynasty, Taoism actively participated in funeral ceremonies.

Figure 3.

Ma Zhi’s epitaph and cover.

In addition to this, the first line of Wu Tong’s epitaph, “The Epitaph of the Late Magistrate Wu of Guangnian County of the Great Sui”, is written in a mixed style of seal and clergy scripts, which is clearly different from the commonly seen clergy script used for later epitaphs. This is often seen in the epitaphs of the Northern Dynasties (北朝), for instance, Kou Zhi’s (寇治) (458–525) epitaph and Kou Kan’s (寇偘) (484–526) epitaph. Scholars have pointed out that this phenomenon has a close relationship with Taoism (See Hua 2008). According to the Book of Wei (Weishu, 魏書), after Kou Qianzhi (寇謙之) (365–448) claimed that when he accepted the title of the Heavenly Master, Li Puwen (李普文), the great-grandson of the “The Supreme Venerable Sovereign” (Taishang laojun, 太上老君), taught him the Perfect Book of Registers and Charts (Lutu zhenjing, 錄圖真經) and created a style that combined the seal and clergy scripts. There are similar records in The Seven Bamboo Tablets of the Cloudy Satchel (yunji qiqian, 雲笈七籤), which demonstrates that the combination of seal and clergy scripts found in Wu Tong’s epitaph was influenced by Taoist culture.

Second, the content of Wu Tong’s epitaph comes from Taoist classics.

Compared with Ma Zhi’s epitaph, Wu Tong’s epitaph reflects a stronger Taoist influence. This is not only demonstrated in the hexagram painting and the combination of seal script and clergy scripts but also by the format and content of the text. As far as the format of the epitaph is concerned, there are 20 words on the left side of the epitaph of Ma Zhi:

天帝告冢中王氣,五方諸神,趙子都等等马先生善人.

“The Heavenly God told the auspicious qi in the tomb, gods of the five directions, and Zhao Zidu that Mister Ma was a kind man.”

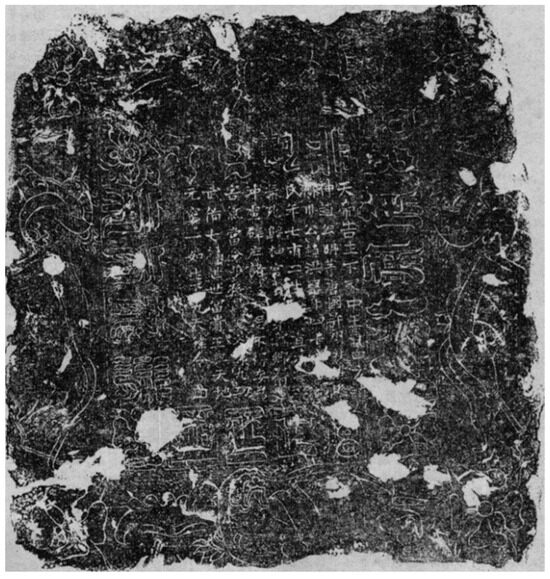

Although this is inconsistent with the content of Ma Zhi’s epitaph, the sentence is seen on the side of other epitaphs. For example, Wu Tong’s epitaph also contains the sentence “The Heavenly God told the auspicious qi, gods of the five directions, Zhao Zidu, and so on…” in the tomb (See Wang 2013a), but these sentences are inscribed under the epitaph and are related to the epitaph text. What is more important is that the inscription of Wu Tong’s epitaph is different from the traditional epitaphs that eulogize and mourn the dead, but is consistent with Taoist magical spells. If we compare it with the epitaphs from the Sui and Tang dynasties, the most similar inscription to Wu Tong’s epitaph would be that of Zhao Hongda’s (趙洪達) (fl. early 7th century) tomb-quelling text (zhenmu wen, 鎮墓文) from the early Tang Dynasty (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The tomb text of Zhao Hongda.

The text is as follows:

天帝告土下塚中王氣、四方諸神、趙公明等:唐國許州扶溝縣□川公趙洪達,年四十;夫 人□氏,年七十二。生值 清真之氣,死歸神宮,翳 身 冥鄉,潛 寧沖虛,辟斥褚禁忌,不得妄為害氣,當令子孫昌熾,文 詠九功,武備七德,世世富貴王,與天地無窮,一如土下九天律令。

“The Heavenly God told the auspicious qi in the tomb under the ground, gods of the four directions, and Zhao Gongming: Zhao Hongda, Lord of (a character missing) chuan, of Fugou County, Xuzhou Prefecture of Tang, aged forty. His wife Lady (a character missing) aged seventy-two. When he was alive, he enjoyed the pure and true qi; after he died, he returned to the Spiritual Palace. His body hides in the land of the deceased; quietly he returns to the world of immortals. I drive out and banish those evil and prohibited; they should not dare to cause any harm. His descendants should flourish, their civil services are celebrated by the Nine Achievements, and their military duties are completed by the Seven Merits. Each generation will be rich and noble and enjoy endless prosperity in heaven and earth. This acts as the law and command of the underground world and the world of the nine heavens” (See Hennan sheng wenhua ju Wenwu gongzuodui 1965).

Scholars agree that the content and format of this tomb inscription come from Tao Hongjing’s (陶弘景) (456–536) Zhengao (真誥) (Declarations of the Perfected). Tao Hongjing was an important figure in the Shangqing School (上清派) of Taoism in the Southern Dynasties (南朝) (420–589). His Zhengao systematically summarized the Shangqing Classics and created the Maoshan Sect (茅山宗).

For the convenience of comparison, the following is a transcript of the relevant text of chapter ten of Zhengao:

夫欲建吉冢之法,……題其文曰:“天帝告土下冢中王氣、五方諸神、趙公明等:某國公侯甲乙,年如千歲,生值清真之氣,死歸神宮,翳身冥鄉,潛寧沖虛,辟斥諸禁忌,不得妄為害氣,當令子孫昌熾,文詠九功,武備七德,世世貴王,與天地無窮,一如土下九天律令。”

“As for the method of building an auspicious tomb ……It should be written with the following: The Heavenly God told the auspicious qi in the tomb under the ground, gods of the five directions, and Zhao Gongming: Lord so-and-so of a certain kingdom, passed away at an old age. His life was created by the pure and true qi; after he died he returned to the Spiritual Palace. His body hides in the land of the deceased; quietly he returns to the world of immortals. I drive out and banish those evil and prohibited; they should not dare to cause any harm. His descendants should flourish, their civil services are celebrated by the Nine Achievements, and their military duties are completed by the Seven Merits. Each generation will be rich and noble and enjoy endless prosperity in heaven and earth. This acts as the law and command of the underground world and the world of the nine heavens” (Tao 2011).

By comparison, it is clear that Wu Tong’s epitaph is basically the same as the text of Zhengao, especially the first sentence and inscription, which suggests that Wu Tong’s epitaph is copied from Zhengao.

At the same time, we should also note that Wu Tong’s epitaph contains such contents as name, native place, lineage, official achievements, and burial location—contents that are not found in Zhengao. The reason is that these pieces of information are part of the epitaph, which is commonly seen in the “epitaphs” before Wu Tong. However, it should also be noted that there are differences between Wu Tong’s epitaph and traditional epitaphs in terms of form and content. Therefore, Wu Tong’s epitaph is a combination of the tomb epitaph and the tomb-quelling text.

It is important to ponder on the rich Taoist contents in Wu Tong’s epitaph. This paper argues that there are two reasons behind its formation:

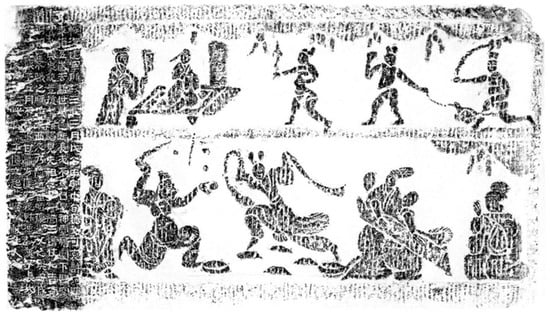

First, Taoism has long been involved in funeral activities. Since the emergence of Taoism in the Eastern Han (東漢) Dynasty (25–220), Taoists claimed that religious rituals have the functions of bringing good fortune, remedying sins, and avoiding misfortunes, which are closely related to funeral activities. The most direct proof of this relationship is that a large number of tomb-quelling texts and land deeds with Taoist influences appeared in Eastern Han tombs. It was during this period of time that tomb-quelling texts and land deeds functioned as epitaphs before the real epitaphs matured in the Northern and Southern dynasties. One example is the soul-calling text (zhaohun ci, 招魂辭) found in a tomb buried in 92 CE in Suide (綏德). The first half of the text records the name, official posts, date of death, and burial place of the deceased, which are typical contents for an epitaph. However, the second half contains charms calling the soul of the deceased and conveys a strong shamanistic color (See Yulin diqu wenguanhui and Suide Xian Bowuguan 2002). In the tomb-quelling text unearthed from a tomb buried in 147 CE in Sanli cun (三里村), Chang’an (長安) County, Shaanxi (陝西) Province, records of the date of death and the age of the tomb occupant are also included (Shaan xi sheng Wenwu guanli weiyuanhui 1958). Similar cases can also be found in the inscription on the stone relief in Xu Aqu’s (許阿瞿) tomb dating back to 170 CE (170) (Nanyang shi bowuguan 1974) (Figure 5). In the Wei-Jin periods, although more formal epitaphs had appeared, information such as the date of death and age of the deceased and the Taoist terminologies were still commonly inscribed in tombs. Because of this, Wu Tong’s epitaph, with a combination of epitaph and tomb-quelling text, demonstrates the role Taoism played in funeral culture during early medieval times.

Figure 5.

Inscription on the stone relief in Xu Aqu’s tomb.

Second, it was influenced by the trend of epitaph-making during the early Sui when Taoism was active in society. The founder of Sui, Emperor Yang Jian (楊堅) (541–604), believed in Buddhism, but he also patronized Taoism. Soon after he established Sui, Yang Jian appointed Zhang Bin (張賓) (fl. 6th century), Jiao Zishun (焦子順) (fl. 6th century), and Dong Zihua (董子華) (fl. 6th century) as officials and appointed many other Taoists as well. Yang Jian also built thirty-six Taoist monasteries to accommodate two thousand Taoists. In addition to this, Yang Jian prohibited the destruction of Taoist statues and provided legal protection for the prosperity and development of Taoism. Moreover, the brief unification of the north and the south under the Sui Dynasty also provided a great opportunity for the integration of different sects of Taoism in the new empire. The Shangqing Classics of the Maoshan Sect, founded by Tao Hongjing, began to spread to the north and gradually became the mainstream of northern Taoism after it combined with Louguan Taoism (樓觀道). More importantly, according to the epitaph, Wu Tong himself believed in Taoism. For example, Wu Tong’s epitaph has two hexagrams from the divinations he made in the sixth and ninth months; it also includes several divination charges. According to Wu Tong’s death month, these two divinations should have been calculated by Wu Tong himself before his death. At the age of eighty-eight, Wu Tong was familiar with the Book of Changes, and there is no doubt that he was a Taoist believer. According to the Book of the Northern Qi (北齊書), Wu Zunshi (吳遵世) (?-?), a native of the Bohai (渤海), began to learn the Book of Changes at an early age. Wu Zunshi eventually became a Taoist and was famous for his divination skills, which gained him patronage from Emperor Xiaowu (孝武) of the Northern Wei Dynasty (r. 532–535). Both Wu Zunshi and Wu Tong belonged to the Wu family of Bohai. Their dates were close to each other, and they were both knowledgeable in Taoism. In addition to this, the epitaph also records that Wu Tong’s name was Sengqie (僧伽), which is a Buddhist term. Although this does not mean that Wu Tong was a Buddhist believer, there is no doubt that Wu Tong was influenced by Buddhism as well. Similar to Wu Tong, there are also Buddhist terms in Ma Zhi’s epitaph, which suggests that Ma Zhi also believed in Buddhism. Moreover, a Taoist stele statue of Laozi unearthed near Luoyang in 1980 contains Buddhist language in its inscription; the statue was carved in 605 (Xie 1984). This highlights the fact that Buddhism and Taoism were equally valued in the early Sui, and Tao Hongjing, the founder of the Maoshan Sect of the Shangqing School, practiced both Buddhism and Taoism. Tao Hongjing eventually integrated Buddhist and Taoist teachings. Thus, because of the spreading of the Shangqing classics to the north, Wu Tong believed in Taoism, and his epitaph was engraved in the Taoist tradition.

There are few materials reflecting the practice of a Taoist funeral ceremony during the medieval age, and research on this mostly depends on the records of extant documents. Stele inscriptions, such as Wu Tong’s epitaph, which have written content and are closely related to Taoism, are therefore very important. Together with Wu Tong’s epitaph, the epitaph of Ma Zhi, found in the early years, and the Sui epitaph with Taoist characteristics, unearthed in Luoyang, demonstrate the folk beliefs in the Luoyang area during the early Sui Dynasty, as well as the influence of Taoist culture on the funeral ceremony that deserve further studies.

This paper is a phased achievement of the National Social Science Fund’s major project “Newly Unearthed Epitaphs and the Editions and Research of Literature and Documents of Sui and Tang Clans” (No. 21 and ZD270) in 2021.

Funding

This article was supported by the 2024 Jilin Province Higher Education Teaching Reform Research Project “Innovative Research and Practice of Jinshi Talent Training Model”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | See (Wang 2023). For a general study of the development of epitaphs in medieval China, see (Davis 2015). See also (Ditter 2014; Choo 2022). |

| 2 | Wang Qi (王氣) refers to the auspicious aura that symbolizes the fortune of the emperor. The Five Gods (五方神) refer to the Eastern Wood God named Jumang (句芒), the Southern Fire God named Zhurong (祝融), the Northern Water God named Xuanming (玄冥), the Western Gold God named Rushou (蓐收), and the Central Earth God named Houtu (后土). Zhao Zidu (趙子都), also known as Zhao Gongming (趙公明), is a Taoist god of the underworld and plague. |

| 3 | The Nine Merits (九功) refer to the nine major contents of cultural education, including the Six Prefectures (六府) and Three Things (三事), which are combined into the Nine Achievements: water, fire, metal, wood, soil, and valley, called the Six Mansions; The three things are to maintain moral integrity, facilitate use, and enrich people’s livelihoods. |

| 4 | The Seven Merits (七德) refer to the seven functions of martial arts, which are used to prohibit violence, eliminate war, maintain strength, consolidate achievements, stabilize the people, reconcile the masses, and enrich wealth. |

| 5 | The incantations in the tombs of Egyptian pharaohs, for instance. |

References

- Choo, Jessey. 2022. Inscribing Death: Burials, Texts and Remembrance in Tang China, 618–907 CE. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Timoth. 2015. Entombed Epigraphy and Commemorative Culture in Early Medieval China. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Ditter, Alexei. 2014. The Commerce of Commemoration: Commissioned Muzhiming in the mid- to late-Tang. Tang Studies 32: 21–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennan sheng wenhua ju Wenwu gongzuodui 河南省文化局文物工作隊. 1965. Henan Fufou xian Tang Zhao Hongda mu 河南扶溝縣唐趙洪達墓. Kaogu 考古 8: 383–88. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, Rende 華人德. 2008. Lun Beichao beike zhong de zhuan li zhenshu zarou xianxiang—Zhongguo shufa quanjii sanguo liangjin nanbeichao muzhi juan bianzuan zhaji 論北朝碑刻中的篆隷真書雜糅現象—中國書法全集三國兩晉南北朝墓誌卷編纂札記. In Hua Rende shuxue wenji 華人德書學文集. Beijing: Rongbaozhai Chubanshe, pp. 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Nanyang shi bowuguan 南陽市博物館. 1974. Nanyang faxian dong Han Xu Aqu muzhi huaxiangshi 南陽發現東漢許阿瞿墓誌畫像石. Wenwu 文物 8: 62–65. [Google Scholar]

- Shaan xi sheng Wenwu guanli weiyuanhui 陝西省文物管理委員會. 1958. Chang’an xian sanli cun dong Han muzang fajue jianbao 長安縣三裡村東漢墓葬發掘簡報. Wenwu cankao ziliao文物參考資料 7: 62–65. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Hongjing. 2011. Zhen Gao. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, pp. 181–82. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Lianlong. 2011. Sui Wu Tong muzhi daojiao wenhua neihan kaolun 隋吳通墓誌道教文化內涵考論. Shijie Zhongjiao Yanjiu 世界宗教研究 130: 12. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Lianlong 王連龍. 2013a. Xinjian Sui Tang muzhi jishi 新見隋唐墓誌集釋. Shenyang: Liaohai Publishing House, p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Lianlong. 2013b. Xinjian bei wei muzhi jishi 新見北朝墓誌集釋. Beijing: Zhongguo Shudian, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Lianlong 王連龍. 2023. Zhongguo gudai muzhi yanjiu 中國古代墓誌研究. Beijing: Zhongguo shehui kexue chubanshe, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Zheng 魏徵. 1982. Sui Shu 隋書. Beijing: Zhong Hua Book Company, p. 76. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Xinjian 謝新建. 1984. Luoyang Dongmagou chutu Suidai shidiao Laojun xiang 洛陽東馬溝出土隋代石雕老君像. Zhongyuan Wenwu 中原文物 1: 110. [Google Scholar]

- Yulin diqu wenguanhui 榆林地區文管會, and Suide Xian Bowuguan 綏德縣博物館. 2002. Shaanxi Suide xian sishi lipu huaxiang shimu diaocha jianbao 陝西綏德縣四十裡鋪畫像石墓調查簡報. Kaogu yu wenwu 考古與文物 5: 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Liguang 趙力光. 1995. Yuanyang qizhi zhai cangshi 鴛鴦七志齋藏石. Xi’an: Sanqin Chubanshe, p. 218. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).