1. Introduction

Contemporary Finnish poetry often takes its readers into forests. Some of these forests are dense, wild, powerful realms of nonhuman sylvan life, while others grow in peculiarly straight shapes and are patched with clearings. The changing landscape of poetic forests reflects the state of Finnish forest areas and echoes the public discussions about forestry and forests. In recent years, forests have become a popular topic and cause for concern, not only because of climate change and biodiversity loss but also because of rapid changes in natural resource use, bio-economy and forest industry. Ecological, economic, political and societal discourses occurring and intertwining in public debates are becoming increasingly present in art and literature as well, marking a new cultural response to the constant question of how humans relate to forests. Although the growth in forest-related topics in Finnish literature and poetry has been generally recognised, academic research on the topic is still scant.

In this article, I explore Finnish poems about forests and clear cuttings. I have selected my research material from three poetry collections: Jouni Tossavainen’s

Metsännenä (Forest Pox,

Tossavainen 1990), Mikael Brygger’s

Valikoima asteroideja (A Selection of Asteroids,

Brygger 2010) and Janette Hannukainen’s

Ikimetsän soittolista (The Playlist of the Primeval Forest,

Hannukainen 2021). My research question is how Tossavainen, Brygger and Hannukainen address forestry and especially clearings in their poetry, including how clearings are represented rhetorically and typographically, what allusions and ideas are attached to clearings, and what roles affects play in descriptions of clearings.

In their poems about forests, Jouni Tossavainen, Mikael Brygger and Janette Hannukainen refer to cultural traditions, knowledges, beliefs, values and stories related to forests and forestry. Moreover, their poems draw form diverse forest discourses and present direct references to the condition of real forests in Finland. This plurality of knowledges and discourses is common in Finnish forest-themed fictional natural writing, and it is also typical of cultural and historical research related to forests and forest use (e.g.,

Rinnekangas and Anttonen 2006;

Mikkonen 2018;

Halla et al. 2020). As there are only a few literary historical studies on Finnish nature writing about forests (

Varis 2003;

Lassila 2011), and research on contemporary poetry about forests is practically missing, I use other types of scholarly sources such as ethnography, environmental philosophy and the cultural and economic history of forests and forestry in my analysis.

Multidisciplinary approaches and wide contextualisation is also common in ecocritical approaches to nature writing (

Garrard 2004, pp. 4–15;

Zapf 2016, pp. 4–5, 11–12). Within ecocriticism, and especially its new materialist branch, the actual physical environments are understood as contexts for writing and reading, as well (

Coupe 2000, pp. 2–7;

Iovino and Oppermann 2014, pp. 2–10). Indeed, it can be argued that literature about forests does not unfold, unless it is carefully contextualised in the enmeshed naturalcultural histories of actual forests.

Although my research material represents one particular cultural area and time, the poems I will discuss share a wider Western tradition regarding forests. In his influential study

Forests: The Shadow of Civilization (1992), Robert Pogue Harrison notes that forests are typically thought of as places that have to be cleared for civilisation to set in. Forests serve as the material basis of culture but they are also regarded as opposite to culture (

Harrison 1992, pp. 3–13, 69–91). In addition to Harrison’s pivotal work, my study is influenced by more recent new materialist research on forests and vegetal life. Eduardo Kohn’s

How Forests Think (

Kohn 2013) combines Peircean semiotics and indigenous knowledge on forests and suggests an approach to forests that emphasises active communication and naturalcultural exchange and learning between humans and nonhumans.

In humanist plant thinking, there appears to be two strands: one that emphasises the poetic agency of plants and forests (

Vieira 2015;

Ryan 2017;

Gagliano et al. 2017), and the other that is more attuned to the cultural and social meanings people have attached to plants and forests (

Szczygielska and Cielemęcka 2019). Often, of course, these strands overlap. Joela Jacobs, for example, insists that while vegetal life participates in poetic practice it also develops “a metaphorical life of its own in the cultural imagination”, “disconnecting” these cultural plant lives “from actual plants and their expressions” (

Jacobs 2019, endnote 2). In this study, too, both aspects are relevant. I am interested in the ways forests and clearings affect the poetics (typography, rhetorics and so on). More importantly, however, I will pay attention to the affective, ecological, ethical and conceptual ideas that poets develop as they write about forest clearings. Therefore, Tim Morton’s approach to ecopoetics as cultural interpretations of anthropogenic environmental change and as a means of evoking a sense of nature’s presence in poetry is important for this study (

Morton 2009,

2010).

In the poems written by Tossavainen, Hannukainen and Brygger, clear cuttings are seen as gaps in the forest that indicate economic growth. Simultaneously, these same gaps indicate disruptions in the natural nonlinear forms that life takes in the forest and, therefore, refer to the destruction of nonhuman life on a more general level. In the poems, the concrete, spatial and material aspects of a lack of trees broaden into aesthetical, experiential, ethical and affective affirmations that reveal the variety of meanings of nonhuman life for humans. I therefore argue that the poems by Tossavainen, Hannukainen and Brygger about clearings represent a specific type of ecopoetics that I call the ‘poetics of lack’. This poetics consists of ideas and rhetorical and typographical elements that together denote and express a variety of experiences, emotions and thoughts regarding a lack of trees, vegetation and nonhuman life more generally. While my focus is on Finnish contemporary poetry about forests, my aim is to participate in wider discussions concerning the cultural representation of forests in the context of current environmental- and natural-resource-related issues, in the North and globally.

As real forests are an important context for my analysis, I will begin this study with a brief section on Finnish forests and forestry. After that, the next two sections will introduce my research materials in their cultural context and the methodology and central concepts of this study. The section following those, with three subsections, will study poems that address acts of cutting, finished clearings and emotive responses to clear cutting. The results of my analyses are then gathered together into a section addressing the poetics of lack, followed by a brief concluding discussion.

2. Forests—The Material Context

Finland is known for its forests. Among visitors coming from more densely populated countries with less forest land, the impressions of endless Finnish forests may stem from actual landscapes outside urban areas. However, the image of Finland as an exceptionally forested country is also actively constructed by the forestry and tourism industries to promote their commercial interests. Just how forested Finland is obviously depends on how forest and other related concepts are defined, and which information sources are used (e.g.,

Räinä 2019, pp. 18–22). Typically, it is stated that around 75% of Finnish land is covered by forests, of which 12% is protected. Most of the protected forests are not subjected to any forestry measures (

Natural Resources Institute Finland 2022a,

2022b;

Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry of Finland n.d.). However, out of the total 26.3 Mha of forestry land, only 0.9 Mha represents old-growth forests (

Sabatini et al. 2018). The rest of the forests show diverse signs of human management or utilisation.

To properly understand Finnish forest poetry, it is important to take into account the material and historical contexts of forests and forestry. As some of the poems I will discuss use forestry-related terminology and comment openly on Finnish forestry practices, it is perhaps useful to mention that clear cutting was introduced in forestry during the 1950s and has been the main method of harvesting wood since then. Clear cutting is the final stage of a long process of forest management, starting from planting saplings, proceeding to fertilisation and selected harvesting, and finally, at the typical age of 60 years, cutting down the whole plantation—nowadays also possibly removing the top layer of the understory (

Rinnekangas and Anttonen 2006). Clear cutting has been a contested method in Finland—its opponents typically use the term “puupelto” (tree field). Interestingly, this term has not been used in poetry, at least to my knowledge. On the other hand, descriptions of unnatural rectangular and straight shapes in forests, implying anthropogenic changes in forest growth, are a recurrent theme in Finnish environmental poetry.

As will be demonstrated in this study, poets also address the wider societal and cultural contexts of forestry. Forest use and forest management are complex practices supported and driven by a vast network of scientific, traditional and experiential knowledge, societal and generational expectations on local, regional and national levels, cultural values, industrial infrastructures and capital. Often diverse interests and viewpoints intersect in forest debates. For example, scientific discussions regarding carbon sequestration have turned into political arguments for green transition and climate change mitigation. Another example is the rapidly changing global forestry industry and market, which causes turmoil in the Finnish forestry industry and politics, as many are still reluctant to acknowledge that the heydays of “green gold” are over. Forests as green gold present a vitally important national narrative as well, as Finland paid its war reparations to the Soviet Union and gained its post-Second World War wealth largely via the forest industry.

Alongside the material contexts of actual forests and forestry, and the wider societal, cultural and historical meanings related to these contexts, Finnish forest poetry also has deep cultural roots, which I will examine next.

3. Changing Forest Poetry

The Finnish cultural history related to forests and forest use is long and manifold. In the context of nature poetry, one important form of forest culture is the oral tradition of Finnish–Karelian–Ingrian folk poetry. Hunting songs were sung by men who wished to succeed in hunting and had to please the forest deities. Songs of sorrow and worry were sung by women who sought consolation in the forest nature, far from the village, people and social troubles (

Seppä 2020). Ingrian people also sang “forest songs” which are songs about moving around in the forests and experiencing the woods and one’s one voice and feelings in the woods (

Timonen 2004, pp. 93–107). All these dimensions of oral tradition demonstrate the importance of interaction between humans and forests as a responsive and powerful realm of nonhuman entities.

A more contemporary layer of forest poetics can be traced to early 1970s. Whereas logging and forestry were typical themes in prose already in the 1930s and 1940s, following realist tendencies to depict the everyday life and societal conditions of the Finnish people, in poetry forests mostly retained their natural (often idealised) condition well into the modernism of the 1950s. During this period, poets rejected the common symbolism largely based on romantic, national-romantic and symbolistic ideas and turned to private imageries and symbols. Many well-known modernists used tree imagery to express their affinity to nature. During the period from the 1950s to the late 1960s, the language of poetry became more speech-like and the themes reflected everyday experiences and private ideas. Poets also increasingly addressed societal issues such as social inequality, economics and politics. The late 1960s also witnessed the rise of a growing environmental consciousness. Together, these poetic developments gave rise to new types of nature poetry. Rapid urbanization, the forestry industry and pollution were addressed by describing devastated forest areas in poetry. Poets like Anne Hänninen, Hannu Salakka, Jyri Schreck and Matti Paavilainen wrote critically about the ways forests gave way to urban development, parks were sorry excuses for forests and even the birds living in the cities were considered to be fake. The forests also changed; trees were perceived as growing in unnatural straight lines and there were no longer old-growth forests, i.e., “real” forests.

After the environmentally conscious decades of the 1970s and 1980s, a second notable wave of environmental poetry emerged in Finland gradually during the 2010s. Into the 2020s, the amount of forest-themed poetry has rapidly increased. From the more than eighty poetry collections published during 2019–2021 that I have read, roughly half have poems about trees and/or forests. What is interesting in the context of this study is that the thematics of clear cutting, first introduced in poetry in the 1960s, re-emerges notably in the 2020s. Once again, poets observe trees growing in rectangular shapes and straight lines. The management of forests is openly criticised and ridiculed. Finnish terminology is important to take into account here; forest management is officially called “metsänhoito”, “metsä” meaning forest and “hoito” meaning care. Following German forestry practices that date back into the late eighteenth century, the Finnish official forest management relies on the idea that forests grow most effectively and stay healthy under human management (

Paaskoski 2008).

For this study, I have selected poems and poetry fragments that explicitly comment on forestry and address the economic, ecological, aesthetical and affective dimensions of clear cutting. The earliest of these is Jouni Tossavainen’s Metsännenä (Forest Pox), published in 1990. Back then, poets in Finland were more generally interested in social, societal and metapoetic issues. Why environmental topics were not very popular during a period from the late 1980s to the 2010s remains to be studied. Since Metsännenä focuses solely on trees, forests and human–forest relations, it is a remarkable piece of Finnish forest writing. The book consists of photographs and poems that for the most part seem to continue from one page to the next (and are therefore called fragments in this study). For my analysis, I have selected fragments that discuss forestry practices, landscape change and emotions evoked by lost forests.

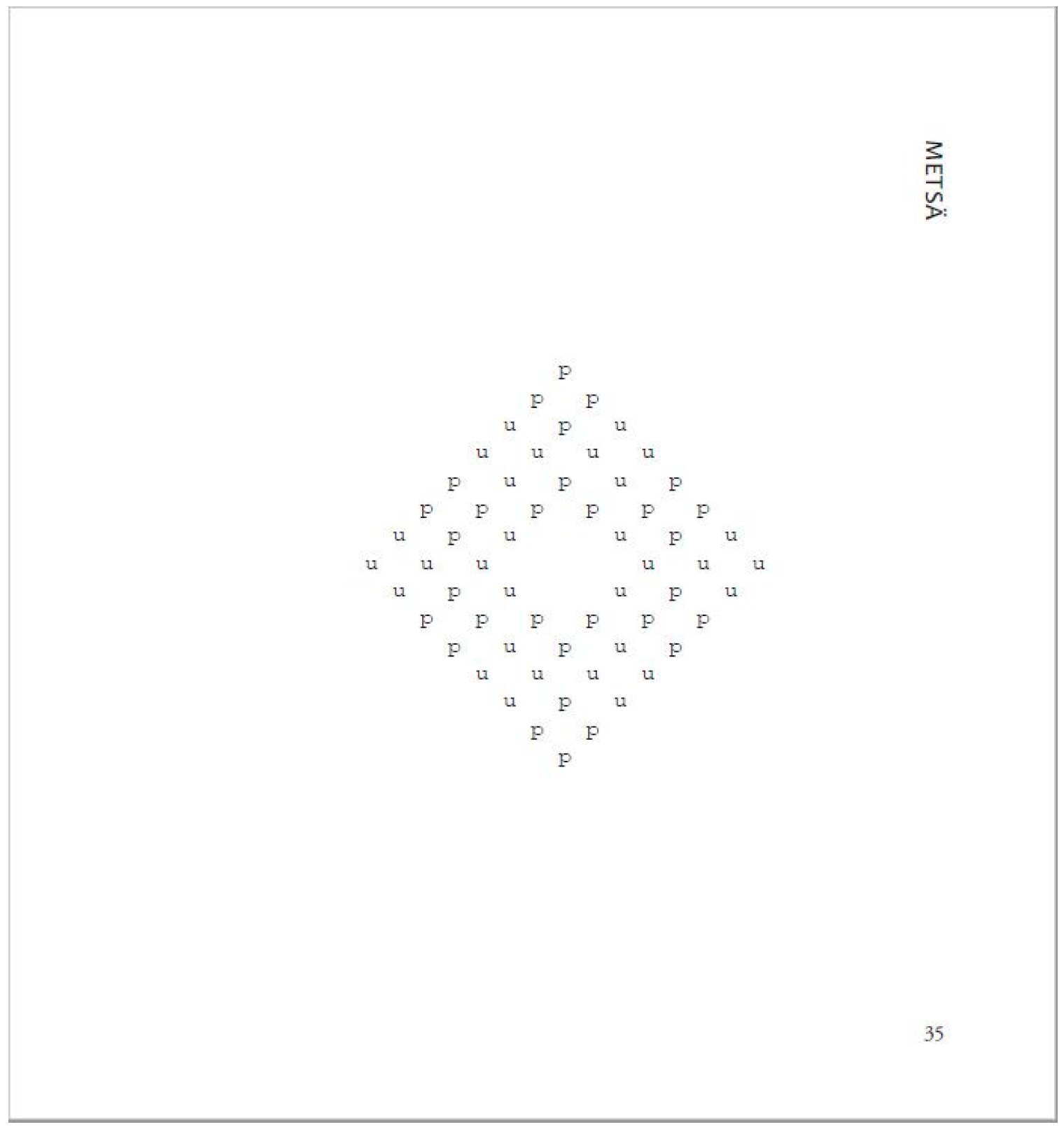

From Mikael Brygger, I have chosen only one poem from his collection Valikoima asteroideja (A Selection of Asteroids), published in 2010. While one might not consider Brygger to be among the most openly environmentalist poets in Finland, his poem “METSÄ” is a wonderful and exceptionally representative example of the kind of forest poetics I discuss in this article. Brygger’s poem is interesting because it can be interpreted to represent a clearing visually, via typography. Visual experimentation is prevalent in Valikoima asteroideja and characterises Brygger’s poetic work more generally, too.

Janette Hannukainen’s Ikimetsän soittolista (The Playlist of the Primeval Forest) is her third poetry collection, published in 2021. Hannukainen’s previous poetry collections are mostly focused on personal experiences and memories. Ikimetsän soittolista is about forests and human–nature relationships, and it also addresses forest issues from a more political and societal angle. It is a playful, even humorous collection of poems about humans managing, using and cutting down forests, longing for them and trying to make sense of them. For this study, I have selected one poem about clear cutting and one about sentiments towards trees.

4. Reading Green

Theoretically and methodologically, my approach to poetry is ecocritical, and more specifically, focused on ecopoetics. Following the etymology (Greek

poiéin, “to make”, “to create”), ecopoetics (or environmental poetics) denotes poetic creation related to nonhuman beings, natural landscapes and ecosystems. In their introduction to

Texts, Animals, Environments,

Middelhoff and Schönbeck (

2019, p. 20) define environmental poetics and ecopoetics broadly as “theoretical and methodological approaches for discussing the relationship between texts and more-than-human worlds”. After a careful discussion of the terminological plurality in ecocritical accounts of environmental poetics and ecopoetics (as well as the nuances of “environmental” and “eco” in ecocritical terminology), Middelhoff and Schönbeck end up emphasising the role of animals (and nonhumans in general) in ecopoetics (

Middelhoff and Schönbeck 2019, pp. 20–24). The term ecopoetics highlights “making” and “creating” as both human and nonhuman activity. “Poetry is not a monospecies event”, as Aaron M. Moe has claimed (

Moe 2014, p. 24;

Middelhoff and Schönbeck 2019, p. 15). Aaron M. Moe, who has done extensive research on nonhuman poetic agency, clarifies that ‘poetics’ refers to the study of ‘poiesis’, which in turn encompasses acts of making and creating. In the arboreal and sylvan contexts, poiesis means not only human creativity but also all kinds of functions of trees where humans can find inspiration, conceptual and narrative contents, multisensory physical closeness and companionship (

Moe 2022).

The poet and scholar John Ryan has developed these ideas in the vegetal context and conceptualises the poetic agency of plants as “corporeal rhetoric of the plant”. Ryan explains how the traits, gestures and functions of plants affect the writing of poetry, and that “the role of the poet is to textualize the sensory data and impressions acquired during the process of being-with botanical things” (

Ryan 2017, p. 134). In the context of his own poetic and creative practices, Ryan also writes about co-authorship with plants (

Ryan 2017, p. 141).

While concepts referring to vegetal poetic agency (phytographia, plant script, phytopoetics, arboreal poiesis) are vital theoretical and conceptual grounds for my work, the term ecopoetics is most relevant for this particular study. Rather than focusing on the meanings and poetic agencies of trees or other single sylvan plants, the motif of clearings in poetry seems to call for a wider perspective. The forest land and ecosystem as a whole must be taken into account, as well as human agency with all the assisting technology, scientific and policy-related discourses, economic motivations and environmental concerns. This multitude is eloquently reflected by

John Ryan (

2022, p. 195) when he defines dendrocriticism as considering “the ways in which the dynamism of trees, forest communities and human-sylvan assemblages shapes the contours of cultural productions”.

Tim Morton has emphasised the power of nature writing to suggest the presence of nonhuman nature to readers. In

Ecology without Nature (2009), they coin the term “ambient poetics” to refer to the environing and simulating effects of writing, how the reader is led to believe they are in direct contact with nonhuman nature (

Morton 2009, pp. 31–54). While this type of simulation is not prominent in the poems I analyse in this study (the poems are too straightforwardly contemplative and critical towards forestry and its effects on human and nonhuman nature), I find Morton’s emphasis on the

human poiésis insightful. By defining ambient poetics as a set of poetic devices aimed at creating a specific sensual impression of being

in a natural environment, Morton’s approach helps to address the evocative descriptions of clear-cut forests in my research material. Also, John Ryan addresses the ways plants’ existence and absence in a physical environment affects writing. Inspired by Jacques Derrida’s philosophy of writing, the concept of “botanical trace” refers to the absence of plants in writing, but not only in semiotic terms (where the referent is always absent in the sign) but in ecological terms, marking the constant threat of extinction (

Ryan 2017, pp. 137–38). Another approach suggested by Ryan is to recognise the physical environment where one’s writing takes place—and where the co-authoring plants grow. Accordingly,

topaesthesia refers to the realisation of one’s own dependence on place, as well as the writer’s attempt to “preserve within the narrative the knotty soil-laden imbrications between plant and place” (

Ryan 2017, p. 140).

Following Moe, Ryan and Morton, in this study ecopoetics refers to the study of the ways the forest structure—the material presence and constellation of vegetation and other nonhuman life—evokes poetic imagery and even affects the visual makeup of the poem. However, while nonhuman sylvan poetic agency is an important dimension in my analysis, human reactions to forestry—ideas and allusions, sense perceptions, emotions—remain the focus in this study. Hence, the concept of ecopoetics also refers to poetic devices that communicate human experiences and ideas regarding forest landscapes, nonhuman creatures of the forest, as well as human activities in the forest.

In addition to the more general views on ecopoetics, I will draw from two more specific conceptualisations that aid me in addressing the discursive and emotional dimensions of Finnish forest poetry. As clearings are the central environmental topos in my study, and poets typically write about them in the general contexts of forestry and forestry practices, terminology related to forestry practices plays an integral part in the sylvan ecopoetics of Tossavainen, Hannukainen and Brygger. Donna Haraway’s concept of technoscience (

Haraway 1997) helps in analysing the allusions to forest sciences and the industrial and economic processes behind forestry, as well as the general logic of maximum profit making behind today’s forestry. To address the emotional and affective dimensions of forestry and clearings, I will draw from Glen Albrecht’s concept of solastalgia (

Albrecht 2005), along with other discussions on environmental anxiety.

Before going deeper into the poems by Tossavainen, Hannukainen and Brygger, I will briefly contextualise the peculiar motif of clearings in Finnish literature.

5. Clearings in Poetry

When forest management and forest resource use is publicly discussed in Finland, often the single most important image representing the aforementioned topics is forest clearing. The clearing symbolises maximum material and financial gain from the forest, and it also embodies extensive land use and landscape change. Moreover, a clearing shows quite concretely the loss of nonhuman life in the forest; where once were plants, animals, fungi and diverse naturally occurring structures (nests, trails), now there is an empty space or an area of tree stumps and land turned upside down. Despite the fact that often these open areas are replanted with saplings, the image of a finished clearing is what captivates attention and provokes reactions. These scenes are typically used in popular scientific illustrated books and photography books about forests and forestry in Finland (e.g.,

Kovalainen and Seppo 2009;

Jokiranta et al. 2019).

The symbolic power of forest clearings is not only based on associations to livelihoods or on the drastic environmental change and its aesthetical and affective responses. There is a wider Western cultural tradition explored in depth by Robert Pogue Harrison in his

Forests: The Shadow of Civilization (

Harrison 1992). Harrison traces this tradition to Giambattista Vico’s interpretation of forest clearings as birth sites of human civilisation in

La Scienza Nuova (New Science) (1744) (

Harrison 1992, pp. 3–13). The idea that forests embody the “excluded other” of human culture, civilisation and social order has had various related interpretations in Western literature from medieval times onwards. Forests are hiding places for people who have violated or cannot fit in the social order, or people who are under persecution. On the other hand, forests are also places where freedom and adventure are possible (

Harrison 1992, pp. 69–91).

In Finnish folklore and cultural imagery, too, forests typically represent all that is wild and untamed; forests can offer shelter from strict social order and expectations, and they also provide all kinds of resources for living. To build a proper human dwelling in the forest, however, entails a clearing and a creation of a household. These types of stories have been popular in Finnish literature throughout its printed history—the most famous example being Aleksis Kivi’s novel Seitsemän veljestä (The Seven Brothers) published in 1870/1873. It is a story of seven brothers turning their backs on society and moving into the forest, to have a brief and frantic episode of absolute freedom.

However, there are also contradicting Finnish stories and mythic ideas that place the origin of human language, livelihoods, practices and even the origin of humanity in the forest. Ancient Finnish folk songs suggest that humanity is related to bears, and that the forest must be consulted and pleased in order to gain game. The forest was believed to have a rule of its own (personified in folklore by the forest deity Tapio and his people) (

Tarkka 2005, pp. 256–99;

Seppä 2020). Finnish environmental philosopher Tere Vadén has interpreted this tradition using the imagery of three spheres: the house, the yard and the forest. Contrary to Vico’s story and Harrison’s interpretation of it, while the house and the yard establish and carry cultural order, the surrounding forest is actually the realm of the original language and dwelling skills. The forest has a language and ways of its own, and they are prior to human language and customs (

Vadén 2010, pp. 23–32). This type of epistemology is in stark opposition to ideas of forests needing to be tamed—clear-cut for culture to set in. In the context of this study, I find it important to stress that in contemporary Finnish poetry forests are both, places of original more-than-human culture and places for human culture to set in.

As a more specific poetic motif, the clearing usually refers to effective forest management, which in turn may carry various symbolic meanings. Often accompanied by descriptions of straight, linear and rectangular shapes in trees and forests, clearings usually symbolise both limitless human activity in forests (or in nature, more generally) and the nonhuman predicament or submission to human rule. This also applies to Tossavainen’s Metsännenä and Hannukainen’s Ikimetsän soittolista, as well as Brygger’s poem “METSÄ”. The poems describe not only clearings and the rationale behind them, but also emotions experienced in witnessing clearings. I will therefore group my material and analyse it in three parts: the first discusses acts of cutting, the second looks into finished clearings and the third addresses emotions related to clearings.

5.1. Acts of Cutting

Forest management consists of various types of practices and activities that change as new technologies, knowledge and managing principles emerge in forestry. In Finnish literature, forest labour has mainly been represented in realist prose, focusing on the hardships of demanding physical work and the peculiarities of forest work culture. Since the early 1970s, however, some poets have also started to write about forestry, often as a means of criticising the extractive forest industry and raising environmental consciousness. Jouni Tossavainen’s Metsännenä is one of the more contemporary works of forest poetry that expresses environmentalist concerns but also examines the multifaceted interests and ideologies behind forestry and the forest economy. Tossavainen openly discusses the means and ends of forestry, often by using special terminology, as in the following example from Metsännenä:

The forest doesn’t give to everyone, they said. Now the crown park has given

its all. For everyone the forest’s amount of space is boundless.

In the preparation of the material the emphasis on tilling the soil is

achieved by mounding, harrowing, burn-clearing, screefing, hoeing,

broadcast seeding and covered seeding, square and tip seeding:

small seedlings, big seedlings, complementary planting, scrubbing off

coverings of grass, mechanically or chemically, as well as thinning

to stop needle loss and defoliation in random sampling.

The final aim in sight is the first objective: active terminal logging.

Instead of an axe in this refinery work the chemical alternative

appears to be a logging accrual that needs to be taken seriously

according to the Act, the statute, and the recommendation. The second

objective is the multi-purpose use of the forest but doesn’t justify passivity

in respect of the first objective. [--]

(Jouni Tossavainen: Metsännenä, p. 36, transl. Emily Jeremiah and Fleur Jeremiah).

Tossavainen’s poem begins with a popular idiom “The forest doesn’t give to everyone”. This saying originates from ancient game culture and highlights the need to please the forest. “The crown park” refers to a newer period, when Finland was under Swedish rule and the forests and forest products were governed by the king of Sweden. The poem continues by making a short reference to the spatial abundance of forests and then moving on to the contemporary ways of ensuring that the forest will give everything to humans. A list of forest management practices ensues, creating a somewhat comical effect (at least for readers who are not familiar with forestry terminology). According to Tossavainen’s poem, “terminal logging” is stated to be the first objective, and the multi-purpose use of forests—that is, combining recreational, economic and industrial uses, and protection—comes only second. This resonates interestingly with Finnish natural resource policy, which has been actively promoting the multi-purpose use of forests.

Tossavainen’s detailed list of forestry practices seems to emphasise the amount of work that is involved in forestry, creating perhaps a hue of ridicule in human activities in the forest—as if the forest would not grow without these management practices. A somewhat similar impression is created in the following poem from Janette Hannukainen’s collection Ikimetsän soittolista:

- Man manages forest

- chops rising saplings with scraping technique

- willow wombs, birch embryos

- trains rears empowers gives

- he manages, landscapes

- bare-root saplings, seedlings with root balls

- it’s a dead angle between twelve and three,

- the bloke’s got a handle on the job, no worries,

- the universe in his glove, man

- m a r-v e l-m a n

- depresses, deposits

- nostalgia swamps, comfort groves

- hey la di la di la

- seeds rain into the silo

- seedlings, seem to be

- n o i s e m o r a s s e s f a v o u r i t e f e n s

- he cares and chops, cuts thin

- fraying mouths mou mou

- MAN,AGES! Hey hoe hoy

- able, capable, divides, drains

- brain mires, intelligence bogs

- man manages, levels, renews

- corny coppices, sacred shrubberies

- he merits, mercifully resto—

- that’s man hey

(Janette Hannukainen: Ikimetsän soittolista, p. 38, transl. Emily Jeremiah and Fleur Jeremiah)

Rather than a list, Hannukainen’s poem might actually be approached as a song, expressing the energy, joy and empowerment connected to manual work in the forests. The poem introduces a rich sylvan life (“willow wombs, birch embryos”) contrasted with human conceptualisations of use and utilisation (“brain mires, intelligence bogs”) and the tireless acts of planting, managing and harvesting. The typography with short lines and frequent commas, and the recurrent shouting of “hey”, enhance the impression of active engagement with the forest—on human terms, of course.

The poems by Tossavainen and Hannukainen quoted above highlight human agency in forests. The expert terms describing diverse procedures in forest management also express the technoscientific knowledge behind forest management.

Donna Haraway (

1997, pp. 3–4) coined the term technoscience for grasping both the practical dimensions of science-driven technical manipulation of things and beings, and the new ontological and ethical situation where clear divides between subject and object, culture and nature, artificial and natural collapse.

When Tossavainen and Hannukainen populate their depictions of forests with forestry terminology, such as the diverse terms for modifying and regulating tree growth, and when they repeatedly describe the technical aspects of forest management and harvesting, they are importing the technoscientific elements of current forest management into their sylvan poetics. Accordingly, there are all kinds on natural, cultural, material and semiotic aspects intersecting in the forests they write about—and this of course mirrors the realities of today’s forests. It is not by accident that the loss of “real forests” is nowadays lamented in Finnish public discussions. Only a tiny part of forests has remained untouched by humans for more than a few decades. Therefore, when

Donna Haraway (

1997, p. 129) writes about “material-semiotic ‘objects of knowledge’, forged by heterogeneous practices in the furnaces of technoscience”, she is writing about genes, microchips, brains, foetuses and bombs, but she might just as well be writing about today’s planted and harvested forests. Indeed, ecosystems are one example of the material–semiotic objects she mentions (

Haraway 1997, p. 129).

In other parts of Ikimetsän soittolista, and especially in Metsännenä, there are various references to satellite technologies, forestry machinery, scientific knowhow and industrial-economic conceptions that together make today’s forests what they are. All of this expresses the technoscientific reality of contemporary forests and poses the question of how humans can and should relate to these forests that are nonhuman nature but are also, at the same time, very cultural. The poems I will discuss next reveal what these forests will look like, once they have reached their end stage in the technoscientific process of forest management.

5.2. Finished Clearings

Mikael Brygger’s collection

Valikoima asteroideja is a varied collection of poems that experiment with typography and diverse sign elements. Forest, or even nonhuman nature, is not a consistent theme of the collection, but the following example (see

Figure 1) ties Brygger’s experimental poetics to the wider history of Finnish environmentalist poetry about forests and forestry:

Brygger’s poem consists of letters ‘p’ and ‘u’ that together constitute words such as “puu” (tree), “pupu” (bunny rabbit) and “puppu” (rubbish talk), as well as “uupuu” (to get tired, to be missing). In the right-hand margin, there is one word in capital letters, “METSÄ”, meaning forest. The hole in Brygger’s poem can be approached from a textual and metalyrical stance. We can ask, does the hole represent a lack or a removal of the letters ‘p’ and ‘u’, or rather, is there a square of white opaque something on top of the text (see

Morton 2010, p. 12)? The poem’s name seems to suggest the first option, that the hole is representing a lack of letters “p” and “u” making the word “puu” (tree), and by extension, a lack of trees. In their essay “Ecology as Text, Text as Ecology”

Tim Morton (

2010, p. 11) suggests that there is an environmental dimension to all written poetry, insofar as it is written and read in a space consisting of words, signs and blank spaces around and between them. This same idea is further developed in Morton’s

Ecology without Nature, where they coin the term ambient poetics to refer to the environing effects of nature writing. In Brygger’s poem, then, a square space emptied of the letters ‘p’ and ‘u’ (which, together, form the word “puu”, tree) creates an impression of clearing.

The idea of this visual poem seems to be quite obvious, at least in the context of Finnish forestry debates and environmental poetry. The straight lines of planted trees and the openings created by clear cutting are well-known imagery and tropes in public discussions, environmentalist nature photography and nature poetry. Trees planted in straight lines and clearings devoid of any vegetation have raised attention among researchers focused on environmental aesthetics and forest sciences alike, and the general understanding has been that hardly any group of people really appreciates the visible results of effective forestry (

Sepänmaa 2006). The rectangular hole in Brygger’s poem refers to formations in nature that are clearly man-made, i.e., unnatural. What is typically expected of wild nature, to be beautiful, is shapes and spaces that are not created or even touched by humans.

In Metsännenä, Jouni Tossavainen writes repeatedly about the anthropogenic sceneries one encounters in today’s forests:

- Now the forest is made up of trees, a relatively dense field of trees

- in straight lines and a clearing, sometimes a wild forest or a tree

- reservation. It’s one of the safety areas of an airport, a black surface,

- which ate the light so that a human doesn’t find a door out of this land.

(Jouni Tossavainen: Metsännenä, p. 20, transl. Emily Jeremiah and Fleur Jeremiah).

- Thus an even-headed forest has been accomplished in place of trees.

- It radiates ‘zero’ and ‘one’ into the satellite. The number is changed in turn

- into visible colours, into a visor video, which rationalises the timber usage

- of the motor logger in the focal areas in practice.

(Jouni Tossavainen: Metsännenä, p. 39, transl. Emily Jeremiah and Fleur Jeremiah).

Both citations describe places where trees embody some specific idea, need or function that humans have for them. In the first excerpt, trees are addressed as planted material, members of a place deemed (and kept) wild, or as parts of an area that merely surrounds a more important place, namely an airport. Rather than individual trees, the second excerpt describes a forest as an area taken into total technoscientific control by information technology and logging machines. This forest is “even-headed”, embodying its anthropogenic history, and it “radiates ‘zero’ and ‘one’ into the satellite”, describing it as communicating with human technology. Interestingly, this communicating timber is called a “forest” “in place of trees”. Is Tossavainen contrasting individually growing trees here with a uniform, timber-producing forest?

Tossavainen’s poetry about clearings does not represent total lack with the same sense and means as Brygger’s poem “METSÄ”. Rather, Tossavainen seems to play with the diverse meanings and expectations of what a forest should be like. The linear shapes, forms and masses entail something that in an economic sense are forests but that really do not sustain “real” forest life, even if trees are still growing there. In a sense, these types of straight-lined tree plantations are clearings always and already. The empty or black square is a recurrent motif in Metsännenä, manifesting the recurrent end image in all representations of planted forests.

The clearings are often described in forest poetry as spatial, visual and even geometrical realities. They are not (only) represented as a lack of trees or sylvan life, but rather, holes in the density of vegetation. Grasping the essence of these peculiar kinds of holes is not easy, because they seem to imply an amalgam of several different types of lack: lack of nonhuman life and lack of specific natural (non)order, generation and flourishing of sylvan life. Moreover, these holes seem to impose something new, extra, extraordinarily human on the forest; they leave an imprint, a trace, a shape and a new kind of forest space that consists of tree trunks and misplaced vegetation and rocks (see

Ryan 2017, p. 138).

From the perspective of ecopoetics, there are multiple ways to read these holes. Tim Morton’s concept of ambient poetics refers to poetic devices that create a sense of environing nature. In this way, Brygger’s square empty hole in the middle of letters ‘p’ and ‘u’ plays with our spatial experiences of forests and forest clearings and situates us in a clearing. On the other hand, we can turn to those conceptualisations of ecopoetics that highlight the way the nonhuman material world affects and influences the ways poets write. When Tossavainen repeatedly describes straight lines of trees and clearings, we can detect subtle ways that actual forests and experiences in these forests affect the ways they are written about, as

John Ryan (

2017, p. 140) has suggested with his concept of topaesthesia.

Like many other particular phenomena (time, life, death, et cetera), holes have posed a specific dilemma for philosophers. Roberto Casati and Achille Varzi, for example, note that holes are characterised by dispositionality and causality. We tend to think of them in terms of what they might be filled with and in terms of their emergence or creation (

Casati and Varzi 1995, pp. 5–6). Although these kinds of observations can generally help in thinking about clearings as holes in forests, the philosophies of holes typically discuss holes in singular objects, not holes as empty spaces amidst larger spaces filled with varied objects (vegetation, understory, rocks, trunks, et cetera). I wanted to refer to the philosophy of holes, albeit briefly, because this perspective highlights the spatial and shape-related elements important in perceiving and experiencing clearings in forest environments, and in poetic texts as organised sign patterns. Eventually, however, clearings are perhaps more accurately described with the concept of lack than with the concept of hole. And lack, of course, implies also emotive dimensions to which I will turn next.

5.3. Emotive Responses

Fascination with forests and trees has been a constant theme in Finnish nature poetry. This fascination is based on many kinds of meanings and values: natural beauty, the closeness and even observed similarity between humans and individual trees, ecological and environmental values, traditional beliefs related to trees (such as trees protecting families and houses, trees inhabiting the spirits of ancestors, and so on). Against these manifold cultural and literary traditions, it is not surprising that clearings and the cutting of individual trees evoke strong negative emotions and responses in contemporary Finnish poetry. In her collection Ikimetsän soittolista, Janette Hannukainen writes affectionally about a singular tree and, simultaneously, laments the ways people treat trees and forests:

- O thou tenderest set of lungs

- my most desired donor of oxygen

- my greenest of all greenery

- my murmuring mender of weeping wounds

- my barren bronchus and my peer

- of a torched tropic.

- Woe is me, a wretched feller

- waster of a thousand logs

- cursed cutter of comely aspens

- plunderer of pining pinewoods.

- Stretch spruce, fight to flourish

- as our swishing shade in sun

- wondrous weeping willow wed the frost

- cast off catatonia callow catkin

- rise birch and remedy

- the nations’ dismal destiny.

- Scoff the carbon of the somber satanic sky

- be bridegroom of the population and the people

- to headbutt off the baleful butchers

(Janette Hannukainen: Ikimetsän soittolista, p. 46, transl. Emily Jeremiah and Fleur Jeremiah).

The poem echoes Finnish folk songs on many different levels. The language of the poem is old-fashioned, even archaic, and rhythmically it is reminiscent of the poems in the national epic

Kalevala. It calls the trees by many names and lists the various good things that trees and forests give to people. This sort of engagement, at once giving thanks, paying honour and asking for more services, is familiar from the old Finnish hunting songs and spells (

Tarkka 2005;

Seppä 2020). The poem consists of a plethora of emotions: admiration for the trees, shame and guilt on behalf of humans, trust and hope for the future, and excitement and inspiration from the powers of the trees and forests. Hannukainen’s poem reflects diverse emotions raised by environmental change and can be therefore analysed in the context of recent discussions on eco-anxiety. In his analysis of the meanings and uses of the concept of eco-anxiety across various disciplines,

Panu Pihkala (

2020) demonstrates the complexity of emotions connected to eco-anxiety. These include fear, guilt, grief and shame. In Hannukainen’s poem, the future seems grim and dark under a “satanic” sky (the original text says “hiisitaivas” which refers to an ancient sacred place Hiisi, later given more malevolent meanings as a trickster spirit or even an evil deity). What is notable in the context of forestry and clearings is the way the speaker expresses guilt, shame and repentance: ”Woe is me, a wretched feller waster of a thousand logs”.

Guilt arising from the cutting down and hence wasting of trees is a relatively new type of sentiment in Finnish environmental poetry, connected with rising environmental consciousness. Although Finnish folklore consists of beliefs regarding trees that cannot be harmed without causing harm to humans, these taboo trees are typically individual trees containing ancestral spirits. Using trees and forests in general was accepted, as long as nothing was wasted. Only when forests started to disappear as a result of excessive use during the 1800s, and again during the rapid urbanisation of the 1950s, did people start to discuss the fate of forests. Jouni Tossavainen’s Metsännenä witnesses the sentiments arising from the increasing use of forests:

- I know that the forest has a periphery, an edge and a side. I know,

- I don’t fear what’s beyond the forest. Thanks to the laboratory

- economy, I don’t need to expect anything surprising

- behind your trees. The forest ascends to wildness only on wheels,

- on iron girders, which become increasingly heavy as the

- transport journey shortens.

- [--]

- There’s no squirrel forest, no hare forest. I don’t go fishing in the woods. There’s

- a poetry forest, there’s a money forest

- in the head of every individual who can read.

(Jouni Tossavainen: Metsännenä, p. 19, transl. Emily Jeremiah and Fleur Jeremiah).

The above citation from Tossavainen contains plenty of references to Finnish forest and forestry traditions. It has been suggested that the word “metsä” originally referred to an edge or border, and the realms of forests have also been typically understood as the borders or regions beyond culture or the human realm (

Rinnekangas and Anttonen 2006). All this is tamed by the modern forest economy and industry, or the ”laboratory economy”, referring probably to the technoscientific dimensions of forestry. Wilderness has been replaced by the wildness of the railways and trains carrying timber. Moreover, the traditional hunting culture has been replaced by late-modern logics of value production; instead of game animals, the forests now produce monetary and cultural values. The excerpt also mentions fear, which is a recurrent theme in

Metsännenä. Fear seems to be connected to unknown or unexpected elements, or experiences of surprise. The following citation returns to the feeling of fear when confronted with wild forests:

- that’s when the real tree terror

- strikes your breast. A human begins to feel afraid. He imagines

- that he sits in a real forest, alone, though there are sticks aplenty

- from the side as far as the edge at almost every second step.

(Jouni Tossavainen: Metsännenä, p. 14, Transl. Emily Jeremiah and Fleur Jeremiah).

Being alone in “a real forest”—a forest untouched by humans—would bring with it a sense of fear. However, the forest remains imaginary as there are plenty of “sticks” (not trees!) to keep one company. In the next excerpt, an ancient, traditional dimension to the fear of forest is introduced, as the speaker confesses to having caught “forest pox” or metsännenä (literally: forest’s nose) after being scared of the forest:

- I went into the forest, I caught forest pox, a disease

- that strikes when you’re frightened.

- The only remedy is said to be to beg the pardon

- of the forest. They also believe that the correct way to beg

- is only known to a whizz kid who examines the symptoms with a die.

- No luck, the die failed to bounce into the right star sign:

- I’m still scared

- that I won’t see a healthy spruce

- or forest.

(Jouni Tossavainen: Metsännenä, p. 29, italics in the original text. Transl. Emily Jeremiah and Fleur Jeremiah).

The fear related to forests gains a new dimensions and contents; rather than fearing the wild unknown forest, the speaker fears there is no “healthy spruce or forest”. In the context of Tossavainen’s collection, it is possible to interpret “healthy” as wild, untouched or freely growing. Read in this way, Tossavainen’s lines evoke solastalgia, a painful feeling evoked by an approaching, inevitable loss of an important, home-like place (

Albrecht 2005, p. 48). The concept of solastalgia was coined by environmental philosopher Glenn Albrecht to refer to feelings of loss related to environmental change. In Tossavainen’s

Metsännenä, humans generally are changing (and even destroying) forests and are therefore perhaps to be blamed if no healthy forests exist anymore.

However, metsännenä (translated as forest pox) poses another possible interpretation of the lines cited above. In Finnish folklore, metsännenä is a disease transmitted by the forest once one is frightened by it. A person contaminated with “metsännenä” may be healed by asking for forgiveness from the forest, possibly with the help of a shaman (

Tarkka 2005, pp. 296–98). In Tossavainen’s poem, the old beliefs are perhaps deprecated by the speaker as superstition, as references are made to die casting and star signs. At least it is clear that the new fear, related to changed spruce trees and forests, might not be cured by negotiating with the forest.

6. Poetics of Lack

In the beginning of this study, I posed a hypothesis that the poems by Tossavainen, Hannukainen and Brygger represent forests, forestry and clearings in a consistent way that could be described as a poetics of lack. Similar conceptualisations have been used in literary scholarship in diverse contexts, to define and analyse various types of absence, loss, scarcity, paucity or emptiness. Jacques Derrida’s extensive philosophical work on the absences in language and writing are a constant inspiration within literary ecocriticism (e.g.,

Morton 2009). Rhetorical and typographical expressions of emptiness have raised considerable interest in the study of environmental poetry reflecting the Buddhist tradition (

Gaard 2020). Within the environmental humanities, the accelerating loss of species has engendered the field of extinction studies which focuses on the cultural, ethical, ecological and social dimensions of species loss and biodiversity loss (

Rose et al. 2017).

The way I have explored and understood the poetics of lack in my research material definitely resonates with linguistic–philosophical and extinction-related ideas of absence and loss. However, my motivation for suggesting (yet another!) poetics of lack has been pragmatic, above all else. Instead of introducing a new concept for general use in literary studies, my intention is to recognise and name a particular thematic, rhetorical and typographical phenomenon in Finnish forest poetry and, in so doing, invite forest poetry scholars to reflect on the ways lack is addressed in literatures of diverse cultures and historical periods.

With the poetics of lack I was initially referring to rhetorical and typographical expressions of a perceived loss of trees and sylvan life, which broaden into complex sets of emotions, ideas, judgments and experiences regarding trees, forests, uses of forests and human–nature relations more generally. During closer analysis, I discovered that lack is not solely connected to the loss of nonhuman sylvan life, biodiversity or individual trees. Rather, the emphasis seems to be often on the jeopardised nonhuman organisation of vegetation and forests in general. Clearings are not only an epitome of the destruction of trees or of forests—they represent human power imposed on nature, a power that forces the trees to grow and die in formations and timespans that are dominated by humans. This power is expressed typographically in Mikael Brygger’s forest-like letter field, organised in straight lines and empty spaces both inside and outside the grouping of letters. Rhetorically, human power over forests is expressed in Hannukainen’s and Tossavainen’s technoscientific terminology as well as their list-like and song-like phrasings oozing confidence and enthusiasm.

As lack refers to diverse types of loss and change in forests, it also raises various kinds of emotions. The poems analysed in this study show disappointment, fear, regret, guilt, shame and sorrow, but also empowerment and playful (albeit sarcastic) joy arising from resistance. Indeed, forced anthropogenic order in the forests is not solely a source of lament and pessimism. Especially the humour in Hannukainen’s forest poetry seems to stem from a clearly recognised possibility of change. The poem “O thou tenderest set of lungs” can be read as a contemporary re-interpretation of ancient Finnish–Karelian–Ingrian traditions, simultaneously summoning the powers of trees, asking for mercy and forgiveness from them, and anticipating new relations to forests and sylvan life. Tossavainen’s sylvan poetics plays with irony and sarcasm up to a point where it is impossible to find a clear underlying message or ethos—readers may well find themselves both exhilarated and worried in reading his verses of the woods.

Environmental poetry and literature more generally is often discussed from the viewpoint of the emotions they evoke. The poetics of lack, at least in the material analysed for this study, resonates with the ways eco-anxiety is understood nowadays. Feelings of discomforting or fearful uncertainty, unpredictability and uncontrollability rising from environmental change definitely apply to witnessing clearings; will the trees ever grow back, many of the poems by Tossavainen, Hannukainen and Brygger seem to ask. Brygger’s weird rectangular field of letters (as trees) may even raise a feeling of solastalgia. On the other hand, the poetics of lack also addresses social and societal dimensions of eco-anxiety, as it questions the technoscientific practices and ideological orientation toward financial profit making that are so elemental in today’s forestry and natural resource policies. As

Panu Pihkala (

2020) reminds, “eco-anxiety is affected by social pressures and factors and can even be a result of them”. When poets express worry and grief over changing forests, they simultaneously situate themselves among certain groups of people and against others. This is also reflected by

Pihkala (

2020) when he states that eco-anxiety could actually be classified as a moral emotion: an ethical–emotional reaction to environmental devastation.

7. Conclusions

According to my analyses, the poetics of lack serves many purposes; it witnesses the drastic changes happening in real forests, it examines the historical developments and diverse societal causes of these changes, and it shows how various groups and individuals relate to these changes. Moreover, the poetics of lack may be a way to take a stand in environmental debates and speak on behalf of the forests. In the poem “METSÄ” by Mikael Brygger, this environmentalist stance is implicitly evoked via typography; the poems written by Janette Hannukainen and Jouni Tossavainen place their readers in discursive realms of forestry parlance. To readers not acquainted with forestry terminology, this can be simultaneously comical and disorienting—probably intentionally on the part of the poets—in order to create hues of irony and sarcasm. However, the professional forestry terminology simultaneously refers to the technoscientific dimensions and economic motivation behind forestry. In this sense, forestry terms reveal the general utilitarian logic of forestry and demonstrate how ideologies, knowledges and practices are intertwined and produce very concrete outcomes in nature. Irony and sarcasm create an ethical stance toward the witnessed lack of nonhuman sylvan life.

The poetics of lack seems to suggest possibilities for other kinds of human–forest-relationships. In his formulation of arboreal poetics, Aaron M. Moe writes about trees offering humans a physical and a metaphorical place of looking further, reflecting and thinking anew, and in this sense, trees also provide opportunities to “refine an environmental ethic” (

Moe 2022, p. 235). Clearings as physical alterations of forest environments and as motifs in poetry seem to offer something similar; although they are situated on the ground level, they offer spatial as well as temporal views of what is lost and will be lost for decades.

What I have mostly wanted to emphasise with this study, and with the use of the term poetics of lack, is the conviction that clearings in poetry are descriptions of what can be seen in today’s forests in Finland and all over the world. Read in this way, clearings in poetry represent rapidly accelerating environmental changes that are detrimental to forest species and ecosystems, and eventually, to the Earth system as a whole. Clearings in poetry are therefore never only rhetorical devices or topoi. They represent lacks that are witnessed and experienced in actual forests.