Media as Metaphor: Realism in Meiji Print Narratives and Visual Cultures

Abstract

:1. Introduction

In this conjoining of the performance arts with visual and readerly experience, Maeda presents a keen understanding of what is now more commonly conceived of as a complex “media ecology” of the mid to late Meiji period.In short, Shōyō‘s image of an ideal writer is that of an observer who keeps a certain distance from the content of the work. In other words, the author is provided with a seat in the audience of a modern theater, where he or she can look at the actors’ performance from this side of the proscenium and is not allowed to participate directly in the play itself. Thus, if we reduce the theory of reproduction to a theory of spectatorship, or to a theory of the separation of the scene from the seen, we can see that it is not only a theory of literature but also a theory of culture.3

As a way of explaining the paradigm shift from Edo visuality to Meiji print, Maeda compared the narrative positioning of the reader in that story with the panorama hall’s positioning of the narrator and viewer. Just as the architectural structure restricted viewers to be limited to one place at the center of the hall to experience the perspective of the 360-degree view, Mori Ōgai positioned his readers over the shoulder of his main character Ōta Toyotarō to cast a panoramic vision of a modern society through the world of the city of Berlin. Maeda argues that the story layers a panoramic or bird’s-eye perspective of the city with a close-up vision of an intimate personal life.Ōgai clearly had an interest in the Panorama itself; but it is rather in his use of a panoramic viewpoint as a method for comprehending the landscape of the modern metropolis of Berlin that the reader recognizes the imprint of a unique, creative spirit at work. The surest evidence of this panoramic viewpoint is the description of Ōta Toyotarō, the hero of “The Dancing Girl”.

2. The Parallax View: Mori Ōgai through the Stereoscope

“Killing a snake for the sake of a woman—it has an intriguing fairy tale air to it. But I don’t think that will be the end of the story.” …

At this moment, we (like the narrator) are forced to take a critical stance on the narrated happenings, to apprehend the story in contradistinction to the fictions discussed—we are made to take a step back from the story narrated by Okada and to think of his positionality as a narrator who reads romances and fairy tales. This critical position that the story role-plays for the reader should suggest that readers, too, ought to mark some critical distance not only between ourselves and Okada’s narration, but also between ourselves and the narrator’s narration of the entire novel, Wild Geese.7Listening to Okada’s account, I accepted it as a fairy tale of sorts. But I did not tell him what it immediately made me think of. Okada had been reading Chin P’ing Mei, and I wondered if he had not perhaps met up with its fatal heroine, Golden Lotus.

“[S]ee that lotus stem bent to the right about twenty feet out? And the shorter one bent to the left in line with it farther out? I must stay directly in line with those two points. If you see me varying from that line, tell me which way to go so I get back in line.”

The fact that the wild goose that has been inadvertently killed is already associated with Otama stages the fact that Okada and the narrator’s guidance of Ishihara towards the bird in this scene is necessarily doubled with our position vis a vis our comprehension of the novel as referring not merely to the one goose killed but also to the many characters themselves as wild geese. In other words, like Ishihara finding his way in the muck to the wild goose, we too are reliant on both Okada’s story (as filtered through the narrator) and the narrator’s own story to navigate our way (to the wild geese and) through the novel Wild Geese.“Right,” said Okada. “The parallax principle.”

3. Modernism’s Ocular Convergence Culture: Panorama, Stereoscopy, and the Myths of Cartesian Difference

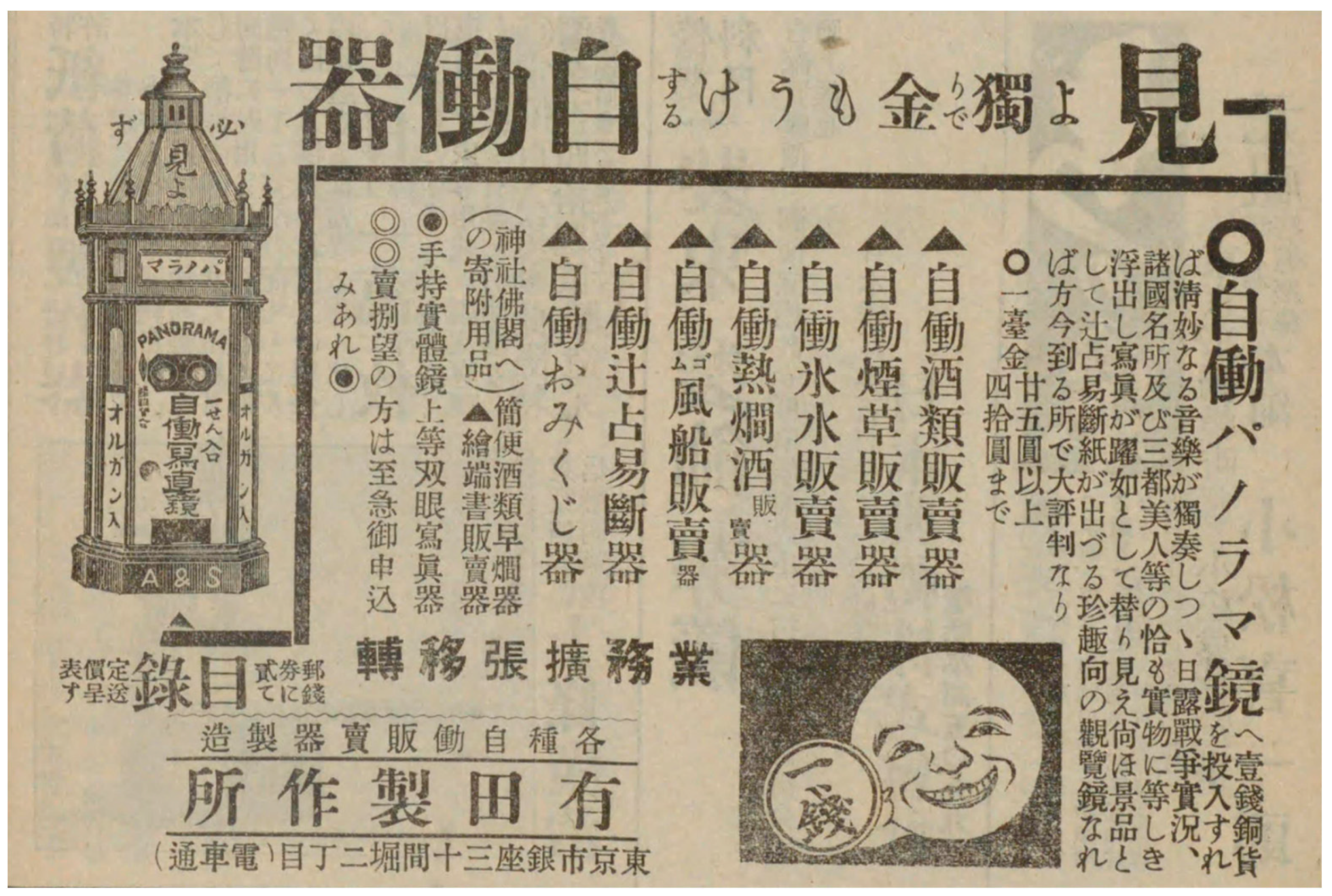

The fact that this stereographic viewing mechanism was billed as “panoramic” in European, US, and Japanese contexts shows that the marketing strategy was deemed to be powerful at the time and, perhaps, not solely because “panorama” sounded more exciting.An examination of the rejuvenated appeal of stereoscopy and its relationship to moving-image devices nonetheless reveals much about the broader social and geographical consumption of popular visual media. It demonstrates the importance of consumption in provincial and rural areas, and the way that a proliferation of penny-in-the-slot devices helped to create penny arcades that offered heterogeneous visual pleasures.

The emphasis here on questions of reality (jikken, jissai ni, shin ni) reveals that, at least at the level of marketing, the halls were engaged with discourses of realism in this early moment of the history of the medium. In the announcement of the US Civil War battle scene’s success abroad, we can see a public history analogue of what had been referred to as “armchair tourism” in the advertising rhetoric of the stereoscope, even as the panorama itself was what travelled.17 In addition, panorama halls were not the only media through which war could be envisioned, popular sets of stereographs included 3D images from the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese wars.18 Marketing of visual forms (stereograph and panorama) used such engagement and connection with the world to cultivate interest.It can be said that this panorama has significant benefits for the public; to give two or three of these—it allows military people actually to observe (jikken) the strategies of General Grant; it really (jissai ni) shows educators remarkable historical points; and informs artists about the truly (shin ni) elegant and splendid power of the brush. This panorama was recently received with cheerful applause in the cities of New York and Chicago, and in the port of San Francisco in the United States of America.16

4. Tricky Media

This self-implicatedness is called immersion in virtual worlds, but the logic articulated by Damisch about European oil painting is the same for stereoscopy and panorama—the aesthetic is a product of the very subject interpellated in its rules.For things and the world to become objects of perception, the subject must pull back from itself, having no vision that doesn’t proceed, ultimately, from such a rotation as well as from the elevation or ostension of the object that is its corollary. But this movement, even its theatrical aspect, remains subject to the law of representation: the distance established by the subject between itself and the object…allows it to escape from the immediacy of lived experience; but only to discover that it itself is implicated, inescapably, in a spectacle whose truth is a function, precisely, of its being so implicated.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The Japanese language leaves open the possibility for a singular or plural reading of the title. Indeed, the novel has been translated both as Wild Goose and as Wild Geese. Though I prefer Burton Watson’s translation as more complete and accurate on the whole, I chose to follow the Ochiai Kingo and Sanford Goldstein plural translation of the title here because it captures the multiple geese (real and metaphorical) depicted in the novel (Mori 1959). Capturing something of what Atsuko Sakaki calls the “polyphonous nature of Gan,” insisting on the plural recognizes that these geese are many and sundry. It is not merely that there is a narrating I and an acting I in the novel, as Sakaki points out many of the other levels of discourse associated with the story-telling of other characters (pp. 141–42). It is particularly strange that in a book entitled Two-Timing Modernity focusing on reoccurring fictional love triangles between two men and a woman, Keith Vincent chooses a singular translation of the title. While, of course, the clear valences of homosociality that Vincent highlights are undeniable, the text (with its cacophony of voices) is even queerer than that. More than simply characterized by a bifurcation between an acting-I and narrating-I alone—a heterogenous dichotomy aptly denied by Vincent’s reading (that insists on the singular reading of Gan, perhaps to emphasize what he will call the “’homodiegetic’ narration” because “boku is both a character and a narrator”(p. 61))—the novel’s narration needs to be thought of as exceeding every schema that at first glance might appear to grasp it. Therefore, in addition to the actual and metaphorical multiple geese in the novel, I think Wild Geese is a more apt translation precisely to foreground these multivocal readings of the style of narration prevalent in all such recent criticism on the novel. (Sakaki 1999, pp. 139–80; Vincent 2012, pp. 43–62). |

| 2 | (Maeda 1982, p. 349). In this regard, the fact that Natsume Sōseki not only painted but, at times, wrote from the standpoint of a painter was significant. |

| 3 | (Maeda 1982, p. 349). These views are also reprised in (Hasegawa et al. 1979, pp. 89–131). For a view that places this visual revolution in fiction in dialogue with realist painting, also see Miya Mizuta Lippit’s citation of Maeda in her essay (M. M. Lippit 2002, p. 16). |

| 4 | Here, it seems Maeda is suggesting something like the contrast between Ōgai’s use of the first-person pronoun yo in “Maihime” and the sentence-ending past tense copula -keri. The work of Tomiko Yoda evokes the possibility of this reading (p. 287). (Yoda 2006, pp. 277–306). See also the narratological distinctions between acting-I and narrating-I in work on autodiegesis and narrating, for example in (Genette 1983, pp. 247–52), and (Cohn 2000, pp. 59–70). While Yoda associates this form of bildungsroman narration with the advent of the modern subject, Maeda is more concerned with the way such juxtaposition itself constructs the panorama-like effect of contrasting a figure with a background. (Maeda 2004, pp. 302–3). |

| 5 | This reading is reminiscent of Auerbach’s gestalt model of mimesis, where the Biblical foreground and the Homeric background mix to form the modern version of realism. (Auerbach 2013). |

| 6 | Significantly, Stephen Snyder refers to the novel as “an uneasy wedding of traditions, the romance and the modern novel.” (Snyder 1994, pp. 364–65). |

| 7 | Here, I am in debt to and in general agreement with Christopher Weinberger, who reads this passage from Ōgai as “a kind of palimpsest in which the immersive world has been overwritten by acknowledgement of its rhetorical, constructed dimensions.” (Weinberger 2015, p. 277). |

| 8 | That Ōgai was aware of and enjoyed the meta-medial component of stereoscopic viewing is evident in another mention of his interest in stereoscopy. Consider this from his German Journals during his time in Berlin, when he mentions how conversation and viewing were coupled: “Tonight Olga and her aunt, who lives across the street from the general store where I am staying, came over with a stereoscope, and we looked at pictures and chatted.” (Brazell 1971, p. 94). |

| 9 | Of course, today we recognize that in form and function, the stereoscope and the panorama hall have very little to do with one another. Media historian Jonathan Crary has been dismissive of the relation between the function and apparatus of the panorama hall and the Kaiserpanorama, writing: “Except for the fact that its [the Kaiserpanorama’s] form was circular, it had no technical or experiential connection to the panorama proper.” (Crary 2001, p. 163; Hosoma 2001, p. 160). |

| 10 | Some models sold items along with views, for instance, one installed at the Jintan tower in Asakusa sold the Jintan mint (Hosoma 2001, pp. 158–59). |

| 11 | Other advertisements for similar machines can be found in all manner of print trade magazines and newspapers through the first two decades of the 20th century. One such vending machine was installed at the Jintan Park next to the Asakusa twelve-story tower, which sold not only the Jintan mints, but also stereoscopic views. See (Saishin jidō jittaikyō 1906). An Arita machine like the one depicted in Figure 1 is on display at the Nihon kamera hakubutsukan. |

| 12 | (Maeda 2004, pp. 65–91). As Maeda Ai examines the panorama in Ōgai without thinking about Ōgai’s interest in stereoscopy, JJ. Origas and Takahashi Seori also mention the visuality and stereoscopy in Ōgai, but neither do so in terms of the panorama. (Origas 1973). |

| 13 | See Ōgai’s comments on the western panorama in his “Yomono yama” and on Harada Naojirō’s sea paintings. (Mori 1923b, pp. 576–77; Mori 1923a, pp. 691–99). See also his general concern for Harada in the fictional depiction of him in Ōgai’s Utakata no ki. |

| 14 | The advent of the first panorama hall was followed in short order by, among others, the Osaka Panorama Hall later that year, the Kanda Panorama Hall in March 1891, the Asakusa Japanese Art Panorama Hall (Asakusa Nihon Bijutsu Panoramakan) in April 1891, the Automatic Panorama in October 1894 (Jidō Panorama, which featured automatons (jidō ningyō) populating the diorama in front of the panorama walls), and the Imperial Panorama Hall (Teikoku Panoramakan) in September 1897. See (Urasaki 1974, pp. 314–18) and (S. M. Lippit 2002, p. 142). For a list of more than 40 different panorama pavilions opened in various parts of Japan between 1890 and 1910, see (Misemono 2013). See also (Okada 1997, p. 102). |

| 15 | Underwood and Underwood, “The Underwood Travel System, Catalog No. 28 p. 4 Illustration: Man Holding Stereoscope, Pointing to Egypt on a Large Globe: Line Drawing.” Smithsonian Institution. https://www.si.edu/object/archives/components/sova-nmah-ac-0143-ref28096 (accessed on 27 January 2023). 87-2132 (OPPS Neg. No.) AC0143-0000001.tif. |

| 16 | Appearing in the 17 May 1890 issue of the Kokumin shinbun in (Urasaki 1974) Nihon kindai bijutsu hattatsu-shi—Meiji-hen (Tōkyō bijutsu, 1974) p. 315 and at http://blog.livedoor.jp/misemono/archives/52115984.html (accessed on 6 August 2023). |

| 17 | On stereoscope and armchair travel, see: (Huhtamo 2006, pp. 74–155). (Hoganson 2007). This discourse about stereograph travel began perhaps even earlier with the mid-meiji peep shows; in 1874, Hattori Bushō wrote: “The peep shows offer the latest curiosities of the world and the customs of every nation. It is like touring the world briefly, and should broaden men’s knowledge while delighting their eyes.” (Hattori 1994, p. 35). |

| 18 | See Enami Nobukuni’s photos in Seiro shashin gachō (Seiro 1904), many of which he would sell as stereographs from his studio on Bentendori in Yokohama. |

| 19 | Here, we should recall that Walter Benjamin noted that another stereo device marketed as a panorama—the Kaiserpanorama—was itself to be compared with the cinema, not because it animated motion but because it automatically served up new pictures. (Benjamin 2008, pp. 75–76). |

References

- Abel, Jonathan E. 2023. The New Real. Minneapolis: University of Minnesotta Press. [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach, Erich. 2013. Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature—New and Expanded Edition. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, Rolan. 1986. The Reality Effect. In The Rustle of Language. Translated by Richard Howard. New York: Hill and Wang, pp. 141–48. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, Walter. 2008. The Imperial Panorama. In The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility, and Other Writings on Media. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brazell, Karen. 1971. Mori Ōgai in Germany. A Translation of Fumizukai and Excerpts from Doitsu Nikki. Monumenta Nipponica 26: 77–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, Dorrit. 2000. The Distinction of Fiction. Baltimore: JHU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crary, Jonathan. 1992. Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crary, Jonathan. 2001. Suspensions of Perception: Attention, Spectacle, and Modern Culture. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crary, Jonathan. 2002. Géricault, the Panorama, and Sites of Reality in the Early Nineteenth Century. Grey Room 9: 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damisch, Hubert. 1994. The Origin of Perspective. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Genette, Gérard. 1983. Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gerbert, Elaine Kazu. 2013. Introduction. In Strange Tale of Panorama Island. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa, Izumi, Maeda Ai, Donald Keene, and Andre Delteil. 1979. Shinpojiumu: 19 Seiki ni okeru Nihon bungaku—Kinsei kara kindai e. Kokusai Nihon bungaku kenkyū shūkai kaigi-roku 2: 89–131. [Google Scholar]

- Hattori, Bushō. 1994. The Western Peep Show. In Modern Japanese Literature: An Anthology. Edited by Donald Keene. New York: Grove Press, Distributed by Publishers Group West. [Google Scholar]

- Hoganson, Kristin L. 2007. Consumers’ Imperium: The Global Production of American Domesticity, 1865–1920. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hosoma, Hiromichi. 2001. Asakusa Jūnikai: Tō no nagame to <kindai> no manazashi. Tokyo: Seidosha. [Google Scholar]

- Huhtamo, Erkki. 2006. The Pleasures of the Peephole: An Archaeological Exploration of Peep Media. In Book of Imaginary Media: Excavating the Dream of the Ultimate Communication Medium. Edited by Eric Kluitenberg. Rotterdam: NAI, pp. 74–155. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, Henry. 2006. Convergence Culture. New York: NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Karatani, Kojin. 2005. Transcritique: On Kant and Marx. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, Henri. 1992. The Production of Space. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Lippit, Miya Mizuta. 2002. Reconfiguring Visuality: Literary Realism and Illustration in Meiji Japan. Review of Japanese Culture and Society 14: 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lippit, Seiji M. 2002. Topographies of Japanese Modernism. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maeda, Ai. 1982. Toshi kūkan no naka no bungaku. Tokyo: Chikuma Shobō. [Google Scholar]

- Maeda, Ai. 2004. Text and the City: Essays on Japanese Modernity. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Massumi, Brian. 2003. Panoscopie: La Photographie Panoramique de Luc Courchesne. CV Photo 60: 27–28. [Google Scholar]

- Misemono. 2013. Misemono kōgyō nenpyō: “Panorama”. Available online: http://blog.livedoor.jp/misemono/archives/52115993.html (accessed on 6 August 2023).

- Mori, Ōgai. 1915. Gan. Tokyo: Moriyama Shoten. [Google Scholar]

- Mori, Ōgai. 1923a. Harada Naojirō. In Ōgai zenshū. Tokyo: Ōgai zenshū kankō-kai, vol. 1, pp. 691–99. [Google Scholar]

- Mori, Ōgai. 1923b. Yomono yama. In Ōgai zenshū. Tokyo: Ōgai zenshū kankō-kai, vol. 1, pp. 576–77. [Google Scholar]

- Mori, Ōgai. 1959. The Wild Geese. Translated by Ochiai Kingo, and Sanford Goldstein. Boston: Tuttle Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Mori, Ōgai. 1973. ‘Panorama’ no koto ni tsukite nanigashi ni atauru-sho. In Ōgai zenshū. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, vol. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Mori, Ōgai. 1995. Gan. In Mori Ōgai zenshū. Tokyo: Chikuma Shobō, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Mori, Ōgai. 2020. The Wild Goose. Translated by Burton Watson. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Noë, Alva. 2012. Varieties of Presence. Cambridge: Harvard University. [Google Scholar]

- Nōshōkō. n.d. Nōshōkō 4(1) Tokyo: Naigai shōhin shinpō-sha 1914-01. Advertisement. p. 12. Kokuritsu kokkai toshokan dejitaru korekushon. Available online: https://dl.ndl.go.jp/pid/1520654 (accessed on 6 August 2023).

- Oechsle, Rob. 2006. Searching for T. Enami. In Old Japanese Photographs: Collectors’ Data Guide. Edited by Terry Bennett. London: Bernard Quarritch, pp. 70–78. [Google Scholar]

- Oechsle, Rob. 2023. A “Gibson Girl” Enjoying Some Quality Time with H.C. White’s Finest Stereoviews. FLICKR. Available online: http://www.flickr.com/photos/24443965@N08/5069586815/?reg=1&src=comment (accessed on 6 August 2023).

- Okada, Richard. 1997. ‘Landscape’ and the Nation-State: A Reading of Nihon Fukei Ron. In New Directions in the Study of Meiji Japan. London: Brill, pp. 90–107. [Google Scholar]

- Origas, Jean-Jacques. 1973. ‘Kumode’ no machi: Sōseki shoki no sakuhin no ichidanmen. Kikan geijutsu 7: 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Plunkett, John. 2008. Selling Stereoscopy, 1890–1915: Penny Arcades, Automatic Machines and American Salesmen. Early Popular Visual Culture 6: 239–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saishin jidō jittaikyō. 1906. Ōsaka Asahi shinbun, [newspaper] August 27. Ishū 8775. p.4. Collection ID 90364899 at the Edo Tōkyō hakubutsukan. Available online: https://museumcollection.tokyo/en/works/6242989/ (accessed on 6 August 2023).

- Sakaki, Atsuko. 1999. Recontextualizing Texts: Narrative Performance in Modern Japanese Fiction. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center Publications Program. [Google Scholar]

- Seiro, Senpō, ed. 1904. Seiro shashin gachō. Tōkyō: Jitsugyō no Nihonsha. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, Stephen. 1994. Ōgai and the Problem of Fiction. Gan and Its Antecedents. Monumenta Nipponica 49: 353–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, Kazuo. 2008. Pachinko tanjo: Shinema no seiki no taishu goraku. Osaka-shi: Sogensha. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, Seori. 2003. Kankaku no modan: Sakutaro, Jun’ichiro, Kenji, Rampo. Tokyo: Serika Shobo. [Google Scholar]

- Urasaki, Eishaku. 1974. Nihon kindai bijutsu hattatsu-shi—Meiji-hen. Tokyo: Tōkyō bijutsu, p. 315. Available online: http://blog.livedoor.jp/misemono/archives/52115984.html (accessed on 6 August 2023).

- Vincent, J. Keith. 2012. Two-Timing Modernity: Homosocial Narrative in Modern Japanese Fiction. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger, Christopher. 2015. Triangulating an Ethos: Ethical Criticism, Novel Alterity, and Mori Ōgai’s “Stereoscopic Vision”. Positions: Asia Critique 23: 259–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, Timothy J. 2016. Mixed Realism: Videogames and the Violence of Fiction. Electronic Mediations. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yoda, Tomiko. 2006. First-Person Narration and Citizen-Subject: The Modernity of Ōgai’s ‘The Dancing Girl’. The Journal of Asian Studies 65: 277–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abel, J.E. Media as Metaphor: Realism in Meiji Print Narratives and Visual Cultures. Literature 2023, 3, 313-326. https://doi.org/10.3390/literature3030021

Abel JE. Media as Metaphor: Realism in Meiji Print Narratives and Visual Cultures. Literature. 2023; 3(3):313-326. https://doi.org/10.3390/literature3030021

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbel, Jonathan E. 2023. "Media as Metaphor: Realism in Meiji Print Narratives and Visual Cultures" Literature 3, no. 3: 313-326. https://doi.org/10.3390/literature3030021

APA StyleAbel, J. E. (2023). Media as Metaphor: Realism in Meiji Print Narratives and Visual Cultures. Literature, 3(3), 313-326. https://doi.org/10.3390/literature3030021