Greek Literature and Christian Doctrine in Early Christianity: A Difficult Co-Existence

Abstract

1. Didactic Autority: Jesus, Paul and Christian Doctrine

on the Sabbath, he entered the synagogue and taught. The people were astonished at his teaching, because he taught them as one having authority.3

Later on, in the second and third century AD, the two famous heads of the Didaskaleion in Alexandria, Clement and Origen, in contrast to the classical and Gnostic tradition, presented Jesus as the unique master (διδάσκαλος), capable of instilling the true doctrine:

The school (διδασκαλεῖον) is this Church (ἡ ἐκκλησία ἥδε) and the only teacher (ὁ μόνος διδάσκαλος) is the bridegroom (ὁ νυμφίος), the right counsel of the good Father, the true wisdom (σοφία γνήσιος), the sanctuary of knowledge (ἁγίασμα γνώσεως).4

He did not persuade people to follow him, neither as a tyrant […], nor as a pirate […], nor as a rich man […], but he acted as a teacher (ὡς διδάσκαλος) who teaches men what they should think of the God of the universe, and the cult they must render to him, as well as the moral custom they must follow.5

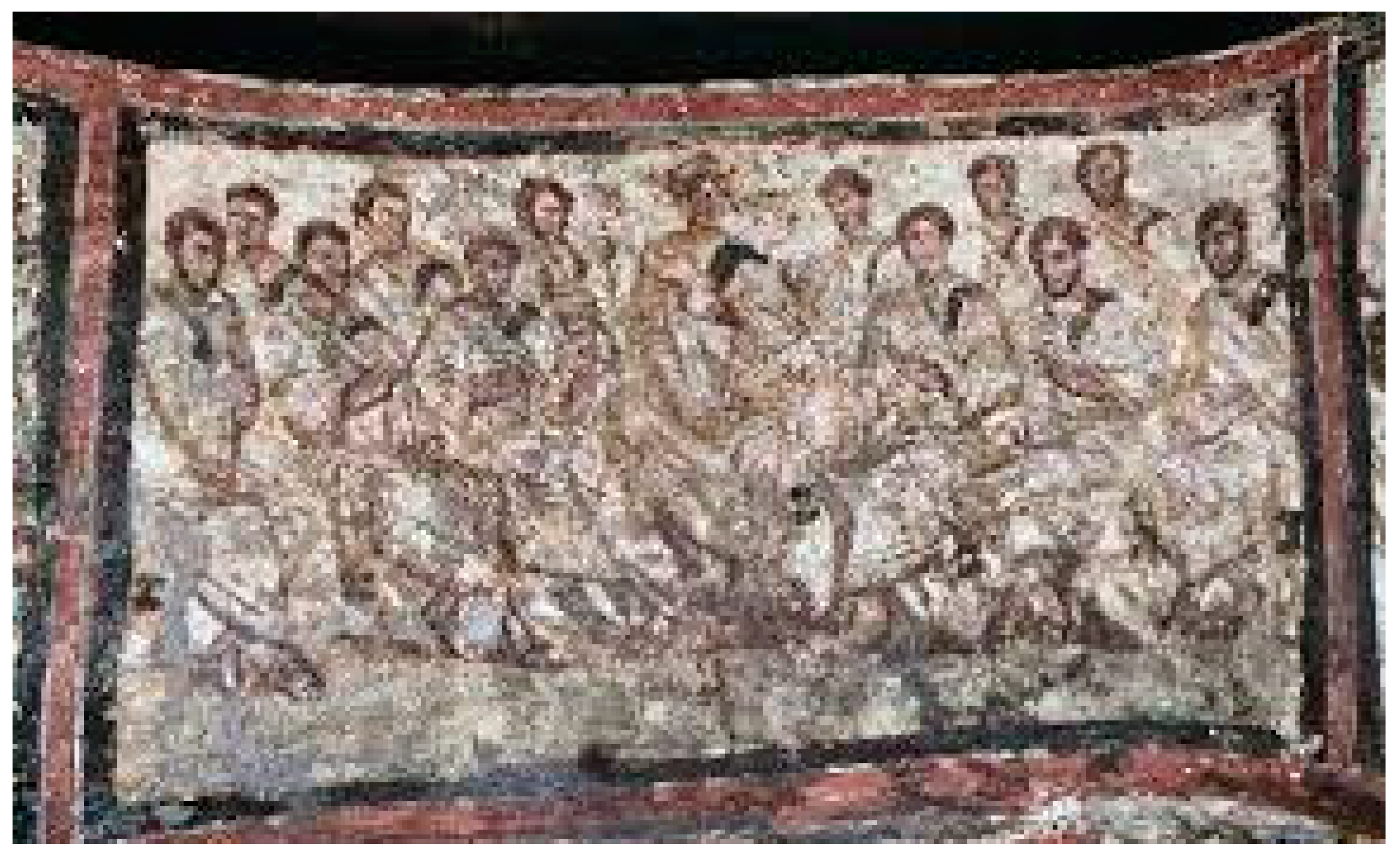

This portrait of Jesus was evident in the arts from the second half of the third century, where Christ, following the model of the ancient philosophers, was revealed as having authority (Testini 1963). Among the frescoes in the anonymous catacomb in via Anapo, along via Salaria in Rome, Christ, dressed in the clothes of a philosopher, is depicted seated and making the gesture of speaking while surrounded by the twelve apostles (Figure 1). Additionally, in the catacomb of Saint Domitilla, Christ is depicted surrounded by his apostles (Figure 2). Such representations emphasize his role as a master.

2. Masters, Culture and Some Controversies

3. Christian Apologetics between Classical Literature and Philosophy

Since I returned to the city of Romans for the second time, I have lived above the baths of Myrtinus, and I know of no other meeting place [scil. of Christians] if not this. If someone wanted to come and to see me, I made him part of the talk of truth.43

Furthermore, in other houses, there were διδάσκαλοι, who imparted Christian teachings to those who wanted to learn them. However, it is under discussion how such a figure between the second and the third centuries could be harmonized with the process of the hierarchization and organization of the Church around the institutional figure of the bishop.44

Most people have missed what philosophy was and why it was sent to men; otherwise, there would have been neither Platonists, nor Stoics, nor Theoreticians, nor Pythagoreans, because philosophical knowledge is unique. Therefore, I want to explain to you how it has become multi-headed. It happened that the followers of those who first embraced philosophy and, for this reason, became famous followed them, not in the search for truth, but only because they were impressed by their fortitude, their temperance and by the novelty of their speeches. Each of them believed that only what he learned from his master to be true, so that they themselves, who transmitted these teachings and other similar ones to their successors, began to be called by the name of those who had the authorship of the doctrine.51

4. The Alexandrian School and Its Relevance

5. Origen and His Model of Philosophical and Spiritual Teaching

They approached him pierced by his words like an arrow—there was in them a mixture of sweet grace, persuasion and force of constraint. However, we were still uncertain and thoughtful, not yet completely convinced to dedicate all our strength to philosophy, but equally incapable, I do not know how, of leaving again, always as if we were attracted towards him by his words, as if they were a necessary constraint.76

6. After Origen: Basil of Caesarea and His Address to Young Men on the Right Use of Greek Literature

7. Concluding Remarks

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Mk 9:5; 10:51. |

| 2 | Mk 1:14. |

| 3 | Mk 1:21–22. |

| 4 | Clem. Alex., Paed. 3,12,98. |

| 5 | Or., C. Cels. 1,30. |

| 6 | Mt. 5–7. |

| 7 | The expression is taken from the work Phaenomena of the Greek poet Aratus of Soli (5), who introduces the kinship of mankind with the deity (τοῦ γὰρ καὶ γένος εἰµέν). These words are also evoked in similar manner by the Stoic Cleanthes, in his famous Hymn to Zeus 4, and in the second century by Theophilus of Antioch (Ad Aut. 2,8). |

| 8 | Hier., Ep. 53,6–7. |

| 9 | For an overview see Cattaneo (1997, pp. 79–92). |

| 10 | Or., C. Cels. 3,9. |

| 11 | Ep. Barn. 1,8; 4,9. |

| 12 | About these two different positions see Prigent (1971, pp. 27–30); 75 n. 5; Neymeyr (1989, pp. 169–73). |

| 13 | For more details see Lugaresi (2004, p. 783). |

| 14 | Socr., HE 3,16,8,27. See also Pack (1987, pp. 185–263, esp. 253–60); Speck (1997, pp. 362–69); Markschies (2002, 97–120, esp. 109–10); Nesselrath (1999, pp. 79–100); Faulkner (2020). |

| 15 | |

| 16 | Aug., Conf. 1,9,14. Augustine’s relationship with the school is discussed in Giannarelli (2001, pp. 9–23). |

| 17 | See note 16 above. |

| 18 | See note 16 above. |

| 19 | Hier., Ep. 22,30. |

| 20 | See note 19 above. |

| 21 | Or., C. Cels. 3,55. As is well known, Celsus’ text has only been preserved thanks to the quotations Origen inserted into his apologetic treatise Contra Celsum. |

| 22 | Or., C. Cels. 3,58. |

| 23 | |

| 24 | |

| 25 | For a discussion see Cantalamessa (1976, pp. 142–69); Hagendahl (1988); Simonetti (2001, pp. 14–27); Jaeger (1966). |

| 26 | |

| 27 | Tat., Orat. 3. |

| 28 | Tat., Orat. 29,2; 31,1–6; 36–41. |

| 29 | Tat., Orat. 33,2 |

| 30 | Tat., Orat. 33,4 |

| 31 | Tat., Orat. 32,1. |

| 32 | Theoph., Ad Aut. 2,8,1–9. |

| 33 | Tert., Apol. 46,10–15; Anim. 3,1; Ad Nat. 2,4,19. |

| 34 | Tert., Praescr. 7. |

| 35 | Tert., Apol. 46,18. |

| 36 | Tert., Praescr. 7,9. |

| 37 | Tat., Orat. 4; 20. For Plato, see Plat., Phaedr. 246ss. |

| 38 | |

| 39 | |

| 40 | Hom., Il. 2,204; 16,856; 23,71. |

| 41 | See, for instance, the incipit of Aristides of Athens’ Apology: «... All-powerful Cæsar Titus Hadrianus Antoninus, venerable and merciful, from Marcianus Aristides, an Athenian philosopher». |

| 42 | For the relationship between Christianism and Platonism see von Ivánka (1992, pp. 7–68); De Vogel (1993). |

| 43 | Acts of Justin 3,3. |

| 44 | For a discussion see Rizzi (2002, p. 47). |

| 45 | Eus., HE 4,16,1. |

| 46 | Eus., HE 4,16,5–6. |

| 47 | Just., Dial. 2,1. |

| 48 | Just., Dial. 2. |

| 49 | Just., Dial. 3–6. |

| 50 | Just., Dial. 7. |

| 51 | Just., Dial. 2,2. |

| 52 | Just., II Apol. 10,2. |

| 53 | Just., II Apol. 13,4. |

| 54 | Just., II Apol. 13,5–6. |

| 55 | Porph., Vit. Plot. 3. |

| 56 | Dio Chrys., Or. 32 Keil. |

| 57 | |

| 58 | Dio Chrys., Or. 32,8–11. |

| 59 | Max. Tyr., Diss. 1,2–7. |

| 60 | Max. Tyr., Diss. 1,8. |

| 61 | |

| 62 | On the debate about the origin of the catechetical school in Alexandria, see Bardy (1937, pp. 65–90); Bardy (1942, pp. 80–109); Van den Hoek (1997, pp. 59–87); Van den Broek (1995, pp. 39–47); Prinzivalli (2003, pp. 911–37). |

| 63 | Eus., HE 5,10,1 ἐξ ἀρχαίου ἔθους διδασκαλείου τῶν ἱερῶν λόγων παρ’ αὐτοῖς συνεστῶτος· ὃ καὶ εἰς ἡμᾶς παρατείνεται καὶ πρὸς τῶν ἐν λόγῳ καὶ τῇ περὶ τὰ θεῖα σπουδῇ δυνατῶν συγκροτεῖσθαι παρειλήφαμεν. |

| 64 | Eus., HE 5,10,1. |

| 65 | |

| 66 | Clem. Alex., Str. 4,162,5. |

| 67 | Clem. Alex., Str. 6,67,1. |

| 68 | See Crouzel (1970, pp. 15–27). Origen was condemned as a heretic in a sixth-century synod, convened by the Emperor Justinian. |

| 69 | The authorship of the Encomium is controversial and debated. Both the manuscript tradition and ancient Christian historiography, starting with the Ecclesiastical History of Eusebius of Caesarea, indicate Gregory Thaumaturgus as the author of the work. However, Pierre Nautin questioned this identification. According to Nautin, the erroneous attribution to Gregory Thaumaturgus was provoked by Eusebius (Nautin 1977, pp. 81–86, 183–96). See also Rizzi (2002, pp. 82–85). |

| 70 | Greg. Thaum., Or. Pan. 1,3. |

| 71 | Greg. Thaum., Or. Pan. 5,57. |

| 72 | Greg. Thaum., Or. Pan. 4,43–46. |

| 73 | Greg. Thaum., Or. Pan. 5,58–59. |

| 74 | Greg. Thaum., Or. Pan. 5,60. |

| 75 | Greg. Thaum., Or. Pan. 6,84. |

| 76 | Greg. Thaum., Or. Pan. 6,78. |

| 77 | Greg. Thaum., Or. Pan. 6,81. |

| 78 | See note 75 above. |

| 79 | Greg. Thaum., Or. Pan. 8,109–114; 9,115–26; 11,133–14,173. |

| 80 | Greg. Thaum., Or. Pan. 11,133–136. |

| 81 | Greg. Thaum., Or. Pan. 11,135. |

| 82 | Greg. Thaum., Or. Pan. 13,156–157. |

| 83 | |

| 84 | Greg. Thaum., Or. Pan. 13,151–155. |

| 85 | Greg. Thaum., Or. Pan. 13,154–156. |

| 86 | Greg. Thaum., Or. Pan. 7,105–107. |

| 87 | Greg. Thaum., Or. Pan. 6,83–86. |

| 88 | Greg. Thaum., Or. Pan. 8,111. |

| 89 | Greg. Thaum., Or. Pan. 13,151–152. |

| 90 | |

| 91 | Greg. Thaum., Or. Pan. 11,142–146. |

| 92 | See Rizzi (2013, p. 112). Also, in the letter to Gregory Thaumaturgus (Ep. 1,8–13), Origen affirms that it is possible to draw from Greek philosophy and classical culture what was useful for an adequate introduction to Christianity, or rather, to better interpret Scripture. |

| 93 | |

| 94 | For the influence of Plutarch in Basil of Caesarea see Valgiglio (1975, pp. 67–86). |

| 95 | About this writing see Naldini (1984, pp. 26–60). |

| 96 | |

| 97 | Diog. Laert. 1,5,88. |

| 98 | For a discussion on the Greek term ἐφόδιον see Naldini (1984, pp. 41–42). |

| 99 | Bas. Caes., Or. ad adol. 2,9. |

| 100 | Bas. Caes., Or. ad adol. 7,1–9. |

| 101 | Bas. Caes., Or. ad adol. 9. |

| 102 | See Naldini (1984, pp. 43–44). |

| 103 | Bas. Caes., Or. ad adol. 8,5. |

| 104 | |

| 105 | For some analogies in these two writings see Naldini (1976, pp. 297–318). |

| 106 | |

| 107 | Greg. Naz., Or. 43,21. |

| 108 | Greg. Thaum., Or. Pan. 11,141–144. |

| 109 | For a detailed analysis on the Delphic maxim of “know thyself” in classical and Christian tradition see Courcelle (1974, pp. 97–101). |

| 110 |

References

- Bardy, Gustave. 1937. Aux origines de l’école d’Alexandrie. Recherches de Science Religieuse 27: 65–90. [Google Scholar]

- Bardy, Gustave. 1942. Pour l’histoire de l’école d’Alexandrie. Vivre et Penser 51: 80–109. [Google Scholar]

- Brontesi, Alfredo. 1972. La soteria in Clemente Alessandrino. Roma: Pontificia Università Gregoriana. [Google Scholar]

- Byrskog, Samuel. 1994. Jesus the Only Teacher. Didactic Authority and Transmission in Ancient Israel, Ancient Judaism and the Matthean Community. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell International. [Google Scholar]

- Cantalamessa, Raniero. 1976. Cristianesimo e cultura. Le esperienze della Chiesa antica. In Cristianesimo e valori terreni: Sessualità, politica e cultura. Edited by Raniero Cantalamessa. Milano: Vita e Pensiero, pp. 142–69. [Google Scholar]

- Cattaneo, Enrico. 1995. La figura del διδάσκαλος nella chiesa antica. In I Padri della chiesa e la teologia. In dialogo con Basil Studer. Edited by Antonio Orazzo. Cinisello Balsamo: San Paolo, pp. 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Cattaneo, Enrico. 1997. I ministeri nella Chiesa antica. Testi patristici dei primi tre secoli. Milano: Paoline. [Google Scholar]

- Cecconi, Giovanni Alberto. 2011. Contenuti religiosi delle discipline scolastiche e prassi d’insegnamento come terreno di conflitto politico-culturale. In Pagans and Christians in the Roman Empire: The Breaking of a Dialogue (IVth-VIth Century A.D.), Paper presented at the International Conference at the Monastery of Bose 2008, Magnano, Italy, October 20–22. Edited by Peter Brown and Rita Lizzi Testa. Münster: LIT Verlag, pp. 225–43. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Raymond. 2008. The Power of Images in Paul. Collegeville: Liturgical Press. [Google Scholar]

- Courcelle, Pierre. 1974. «Connais-toi toi- même», de Socrate à Saint Bernard. Paris: Études Augustiniennes. [Google Scholar]

- Crouzel, Henry. 1970. L’école d’Origène à Césarée. Bulletin de Littérature Ecclésiastique 71: 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Crouzel, Henry. 1987. Cultura e fede nella scuola di Cesarea di Origene. In Crescita dell’uomo nella catechesi dei Padri (età prenicena). Atti del convegno della Facoltà di Lettere classiche e cristiane dell’Ateneo Salesiano, 14–16 March 1986. Edited by Sergio Felici. Roma: LAS, pp. 203–9. [Google Scholar]

- De Vogel, Cornelia. 1993. Platonismo e Cristianesimo. Antagonismo o Comuni Fondamenti? Milano: Vita e Pensiero. [Google Scholar]

- Demoen, Kristoffel. 1993. The Attitude towards Greek Poetry in the Verse of Gregory Nazianzen. In Early Christian Poetry. A Collection of Essays. Edited by Jan den Boeft and A. Hilhorst. Leiden: Brill, pp. 235–52. [Google Scholar]

- Droge, Arthur J. 1987. Justin Martyr and the Restoration of Philosophy. Church History 56: 303–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droge, Arthur J. 1989. Homer or Moses? Early Christian Interpretations of the History of Culture. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Mark. 2008. Apologetics. In The Oxford Handbook of Early Christian Studies. Edited by Susan Ashbrook Harvey and David Hunter. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 549–64. [Google Scholar]

- Engberg-Pedersen, Troels. 1994. Paul in His Hellenistic Context. Cambridge: T&T Clark International. [Google Scholar]

- Engberg-Pedersen, Troels. 2000. Paul and the Stoics. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press. [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner, Andrew. 2020. Apollinaris of Laodicea: Metaphrasis Psalmorum. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, Samuel. 2004. El Discurso verídico de Celso contra los cristianos. Críticas de un pagano del siglo II a la credibilidad del cristianismo. Teología y Vida 45: 238–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannarelli, Elena. 2001. L’infanzia secondo Agostino: Confessiones e altro. In L’adorabile vescovo di Ippona. Atti del Convegno di Paola (24–25 maggio 2000). Edited by Franca Ela Consolino. Soveria Mannelli: Rubbettino, pp. 9–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gnilka, Christian. 1984–1993. Chresis. Die Methode der Kirchenväter im Umgang mit der antiken Kultur. 2 vols. Basel: Schwabe. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, Pilar. 2018. Apuntes de un sofista cristiano en torno a la literatura griega: Ad adulescentes de Basilio el Grande. Emerita, Revista de Lingüística y Filología Clásica 86: 277–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, Pilar. 2023. El revoltoso Momo y el apologeta Atenágoras: Dos miradas sobre la identidad religiosa del s. II d.C. Nova Tellus 41: 89–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagendahl, Harald. 1988. Cristianesimo Latino e Cultura Classica. Roma: Borla. [Google Scholar]

- Hillar, Marian. 2012. From Logos to Trinity: The Evolution of Religious Beliefs from Pythagoras to Tertullian. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holte, Ragjtak. 1958. Logos spermatikos. Christianity and Ancient Philosophy according to St Justin’s Apologies. Studia Theologica 12: 109–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, Anders-Christian. 2009. Apologetics and Apologies—Some Definitions. In Continuity and Discontinuity in Early Christian Apologetics. Edited by Jörg Ulrich, Anders-Christian Jacobsen and Maijastina Kahlos. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, pp. 6–21. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger, Werner. 1966. Cristianesimo primitivo e paideia greca. Firenze: La Nuova Italia. [Google Scholar]

- Joly, Robert. 1973. Christianisme et Philosophie. Études sur Justin et les Apologistes Grecs du IIe siècle. Bruxelles: Éditions de l’Université de Bruxelles. [Google Scholar]

- Karamanolis, George. 2021. The Philosophy of Early Christianity. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, Lillian I., and Samuel Rubenson. 2018. Monastic Education in Late Antiquity: The Transformation of Classical “Paideia”. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Laurin, Joseph Rhéal. 1954. Orientations Maîtresses des Apologistes Chrétiens de 270 à 361. Roma: Pontificia Università Gregoriana. [Google Scholar]

- Lugaresi, Leonardo. 2004. Studenti cristiani e scuola pagana. Cristianesimo nella storia 25: 779–832. [Google Scholar]

- Markschies, Christoph. 2002. Lehrer, Schüler, Schule: Zur Bedeutung einer Institution für das antike Christentum. In Religiöse Vereine in der römischen Antike. Hrsg. Ulrike Egelhaaf-Gaiser und Alfred Schäfer. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, pp. 97–120. [Google Scholar]

- Moffatt, Ann. 1972. The Occasion of St Basil’s “Address to Young Men”. Antichthon 6: 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morlet, Sébastien. 2014. Christianisme et Philosophie: Les Premières Confrontations (Ier-VIe siècle). Paris: Le Livre de Poche. [Google Scholar]

- Naldini, Mario. 1976. Paideia origeniana nella “Oratio ad adolescents” di Basilio Magno. Vetera Christianorum 13: 297–318. [Google Scholar]

- Naldini, Mario. 1984. Basilio di Cesarea, Discorso ai giovani. Fiesole: Nardini. [Google Scholar]

- Nautin, Pierre. 1977. Origène. Sa vie et son œuvre. Paris: Beauchesne. [Google Scholar]

- Nesselrath, Heinz-Günther. 1999. Die Christen und die heidnische Bildung: Das Beispiel des Sokrates Scholastikos (hist. eccl. 3,16). In Leitbilder der Spätantike—Eliten und Leitbilder. Hrsg. Jürgen Dummer und Meinolf Vielberg. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, pp. 79–100. [Google Scholar]

- Neymeyr, Ulrich. 1989. Die Christliche Lehren im Zweiten Jahrhundert. Ihre Lehrtätigkeit, ihr Selbstverständnis und ihre Geschichte. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Normann, Friedrick. 1967. Christos Didaskalos. Die Vorstellung von Christus als Lehrer in der christlichen Literatur des ersten und zweiten Jahrhunderts. Münster: Aschendorffsche Verlagsbuchhandlung. [Google Scholar]

- Nyström, David E. 2018. The Apology of Justin Martyr. Literary Strategies and the Defence of Christianity. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. [Google Scholar]

- Osborn, Eric. 2000. The Apologists. In The Early Christian World. I–II. Edited by Philp F. Esler. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 525–51. [Google Scholar]

- Pack, Edgar. 1987. Sozialgeschichtliche Aspekte des Fehlens einer “christlichen” Schule in der römischen Kaiserzeit. In Religion und Gesellschaft in der römischen Kaiserzeit. Kolloquium zu Ehren von Friedrich Vittinghoff. Hrsg. Werner Eck. Köln-Wien: Böhlau, pp. 185–263. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrino, Michele. 1947. Gli Apologeti greci del II secolo: Saggio sui rapporti fra il cristianesimo primitivo e la cultura classica. Roma: Anonima Veritas Editrice. [Google Scholar]

- Penna, Romano. 2001. Paolo nell’Agorà e all’Areopago di Atene (At 17,16–34). Un confronto tra vangelo e cultura. In Vangelo e inculturazione. Studi sul rapporto tra rivelazione e cultura nel Nuovo Testamento. Edited by Romano Penna. Cinisello Balsamo: San Paolo, pp. 365–90, (previously issued in Rassegna di Teologia 36 [1995], pp. 653–77). [Google Scholar]

- Pépin, Jean. 1955. Le “challenge” Homère-Moïse aux premiers siècles chrétiens. Revue de Sciences Religieuses 29: 105–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernot, Laurent. 2006–2007. Seconda Sofistica e Tarda Antichità. Koinonia 30–31: 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Pouderon, Bernard. 1998. Réflexions sur la formation d’une élite intellectuelle chrétienne au IIe siècle: Les «écoles» d’Athènes, de Rome et d’Alexandrie. In Les apologistes chrétiens et la culture grecque. Sous la direction de Bernard Pouderon et Joseph Doré. Paris: Beauchesne, pp. 237–69. [Google Scholar]

- Prigent, Pierre. 1971. L’Épître de Barnabé (Sources Chrétiennes 172). Paris: Éditions du Cerf. [Google Scholar]

- Prinzivalli, Emanuela. 2003. La metamorfosi della scuola alessandrina da Eracla a Didimo. In Origeniana Octava. Edited by Lorenzo Perrone. Leuven: Peeters, pp. 911–37. [Google Scholar]

- Quiroga, Alberto J. 2009. Nuevas tendencias en el estudio de la retórica griega tardo-imperial. Hacia una Tercera Sofística. Lexis 27: 487–97. [Google Scholar]

- Quiroga, Alberto J., ed. 2013. The Purpose of Rhetoric in Late Antiquity: From Performance to Exegesis. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. [Google Scholar]

- Rappe, Sara L. 2001. The New Math: How to Add and to Subtract Pagan Elements in Christian Education. In Education in Greek and Roman Antiquity. Edited by Yun Lee Too. Leiden: Brill, pp. 405–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ridings, Daniel. 1995. The Attic Moses. The Dependency Theme in Some Early Christian Writers. Göteborg: Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis. [Google Scholar]

- Riggi, Calogero. 1987. Elementi costitutivi della “paideia” nel “panegirico” del Taumaturgo. In Crescita dell’uomo nella catechesi dei Padri (età prenicena). Atti del convegno della Facoltà di Lettere classiche e cristiane dell’Ateneo Salesiano, 14–16 marzo 1986. Edited by Sergio Felici. Roma: LAS, pp. 211–27. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, Marco. 1999. Il διδάσκαλος nella tradizione alessandrina: Da Clemente all’Oratio panegyrica in Origenem. In Magister: Aspetti culturali e istituzionali. Atti del Convegno Chieti 13–14 novembre 1997. Edited by Giulio Firpo-Giuseppe Zecchini. Alessandria: Edizioni dell’Orso, pp. 177–98. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, Marco. 2002. Gregorio il Taumaturgo (?), Encomio di Origene. Milano: Paoline. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, Marco. 2013. La scuola di Origene tra le scuole di Cesarea e del mondo tardoantico. In Caesarea Maritima e la scuola origeniana. Multiculturalità, forme di competizione culturale e identità cristiana. Atti dell’XI Convegno del Gruppo di ricerca su Origene e la tradizione alessandrina, 22–23 settembre 2011. Edited by Osvalda Andrei. Brescia: Morcelliana, pp. 107–9. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, Marco. 2019. Le scuole cristiane dalla periferia al centro del sistema scolastico tardoantico. In Pratiche didattiche tra centro e periferia nel Mediterraneo tardoantico. Atti del Convegno internazionale di studio, Roma, 13–15 maggio 2015. Edited by Gianfranco Agosti e Daniele Bianconi. Spoleto: Fondazione Centro italiano di studi sull’alto Medioevo, pp. 127–40. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, Paul M. 2016. Paul’s Letters and Contemporary Greco-Roman Literature: Theorizing a New Taxonomy. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Rubenson, Samuel. 2000. Philosophy and Simplicity. The Problem of Classical Education in Early Christian Biography. In Greek Biography and Panegyric in Late Antiquity. Edited by Tomas Hägg and Philip Rousseau. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, pp. 110–39. [Google Scholar]

- Sachot, Maurice. 2007. Quand le christianisme a changé le monde I. La subversion chrétienne du monde antique. Paris: Odile Jacob. [Google Scholar]

- Simonetti, Manlio. 2001. Cristianesimo antico e cultura greca. Roma: Borla. [Google Scholar]

- Speck, Paul. 1997. Sokrates scholastikos über die beiden Apolinarioi. Philologus 141: 362–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenger, Jan R. 2022. Education in Late Antiquity: Challenges, Dynamism, and Reinterpretation, 300–550 CE. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Testini, Pasquale. 1963. Osservazioni sull’iconografia del Cristo in trono fra gli apostoli. Rivista dell’istituto di archeologia e storia dell’arte 11–12: 230–300. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, Juan, ed. 2013. Officia Oratoris. Estrategias de persuasión en la literatura polémica cristiana (ss. I-IV). Ilu. Revista de Ciencias de las Religiones. Anejo XXIV. Madrid: Publicaciones Universidad Complutense de Madrid. [Google Scholar]

- Trigg, Joseph W. 2001. God’s Marvelous Oikonomia: Reflections of Origen’s Understanding of Divine and Human Pedagogy in the Address Ascribed to Gregory Thaumaturgus. Journal of Early Christian Studies 9: 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valgiglio, Ernesto. 1975. Basilio Magno “Ad adulescentes” e Plutarco “De audiendis poetis”. Rivista di Studi Classici 23: 67–86. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Broek, Roelof. 1995. The Christian “School” of Alexandria in the Second and Third Centuries. In Centres of Learning: Learning and Location in Pre-Modern Europe and the Near East. Edited by Jan Willem Drijvers and Alasdair A. MacDonald. Leiden: Brill, pp. 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Hoek, Annewies. 1997. The “Catechetical” School of Early Christian Alexandria and its Philonic Heritage. Harvard Theological Review 90: 59–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Ivánka, Endre. 1992. Platonismo Cristiano. Recezione e Trasformazione del Platonismo nella Patristica. Milano: Vita e Pensiero. [Google Scholar]

- Young, Frances. 1999. Greek Apologists of the Second Century. In Apologetics in the Roman Empire. Pagans, Jews, and Christians. Edited by Mark J. Edwards, Martin Goodman, S. R. F. Price and Christopher Rowland. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 81–104. [Google Scholar]

- Zachhuber, Johannes. 2020. The Rise of Christian Theology and the End of Ancient Metaphysics. Patristic Philosophy from the Cappadocian Fathers to John of Damascus. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Franchi, R. Greek Literature and Christian Doctrine in Early Christianity: A Difficult Co-Existence. Literature 2023, 3, 296-312. https://doi.org/10.3390/literature3030020

Franchi R. Greek Literature and Christian Doctrine in Early Christianity: A Difficult Co-Existence. Literature. 2023; 3(3):296-312. https://doi.org/10.3390/literature3030020

Chicago/Turabian StyleFranchi, Roberta. 2023. "Greek Literature and Christian Doctrine in Early Christianity: A Difficult Co-Existence" Literature 3, no. 3: 296-312. https://doi.org/10.3390/literature3030020

APA StyleFranchi, R. (2023). Greek Literature and Christian Doctrine in Early Christianity: A Difficult Co-Existence. Literature, 3(3), 296-312. https://doi.org/10.3390/literature3030020