1. Introduction

EuPRAXIA@SPARC_LAB is a new multi-disciplinary user facility currently under construction at INFN-LNF in Italy in the framework of the EuPRAXIA collaboration [

1]. It is composed of an X-band electron linac, a 60 cm long discharge plasma capillary, and an undulator section, where radiation is generated via the FEL process. A high-brightness linear accelerator driving an FEL requires a comprehensive set of diagnostics devices able to measure with high accuracy and resolution the 6D phase-space of the electron beam at different locations along the machine. In particular, the monitoring of the mean and rms energies of the beam is crucial, for instance, at the exit of the plasma module, to quantify the energy jitter, which significantly affects the FEL performance reproducibility. The determination of the beam energy is also needed at the radioactive beam facility SSRIP, situated at IFIN-HH in Romania [

2]. SSRIP is based on a linac with S-band and C-band RF structures, which accelerate the electron beam to the nominal energy of 100 MeV. The commissioning of SSRIP is planned for 2026, and it will be carried out by INFN-LNF in collaboration with IFIN-HH.

Magnetic spectrometers [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8] are commonly used in linacs to measure the beam energy and its rms. The main element of a magnetic spectrometer is the dipole magnet, which disperses the beam by energy in the horizontal plane. A set of quadrupole magnets is usually installed before the dipole to focus the beam onto a viewing screen positioned after the dipole. The beam energy profile, and thus its mean and rms, is obtained by projecting onto the horizontal axis the transverse beam spot visible on the screen. To estimate the energy

E of an electron knowing its horizontal displacement

x at the screen, the following formulas can be used [

9]:

where

E is in GeV,

(in T) is the average magnetic field experienced by the particle in the dipole,

(in rad) is the design bending angle of the dipole, ad

R (same units as

x) is the distance between the screen and the dipole center, and

(in m) is the length of the arc traversed by a reference particle entering the dipole with

, horizontal angular displacement

, and nominal energy

.

The rightmost formula in Equation (

1) is valid only for small

x values. Rearranging the terms in this formula, one can see that the horizontal displacement of a particle is proportional to its relative momentum deviation

; i.e.,

where it is highlighted that the proportionality constant is an approximated expression for the horizontal dispersion

. Thus, as a first approximation, the dispersion introduced by the dipole magnet increases linearly with the distance between the viewing screen and the dipole.

All the elements of a spectrometer, i.e., the dipole and quadrupole magnets, as well as the viewing screen, should be designed to meet the requirements in terms of energy resolution and accuracy at the screen position. Macroparticle beam dynamics simulations can help significantly in the design of the spectrometer setup. The main idea is to track an initial beam distribution from a starting point up to the screen position, passing through the set of quadrupoles and the dipole. The transverse beam spot at the screen position is projected onto the horizontal axis, which can be converted into energy units by using the leftmost formula in Equation (

1). Then, it is possible to compare the mean and rms of the energy profile at the screen position with the corresponding quantities of the initial energy profile, and this provides the accuracy of the simulated energy measurement. In addition, the image resolution (or bin size) in energy units at the screen can be directly obtained from the converted horizontal axis. The image resolution indicates how well the energy profiles are resolved on the screen, and it depends on the resolution of the camera sensor and on the chosen field of view (FOV). The design of spectrometer setups described in this paper focuses on the monitoring and optimization of the energy accuracy and image resolution.

It should be noted that for a generic particle with a displacement

x at the screen,

in Equation (

1) should be ideally replaced by the length of the path actually traversed by the particle in the dipole. In addition, since the magnetic field inside the dipole is not perfectly flat in the horizontal plane, a generic particle can experience an average magnetic field slightly differently from

. Therefore, the use of the leftmost formula in Equation (

1) to convert the horizontal axis into energy units introduces an error in the evaluation of the energy, and this error affects both the resolution and accuracy of the energy measurement. Nevertheless, it is challenging to avoid this error, as the length of the arc traversed inside the dipole, as well as the experienced magnetic field, is in general difficult to determine for an arbitrary particle. Moreover, the particles related to a given bin of the projected profile could have traveled along quite different paths inside the dipole. Therefore, one cannot associate unique arc length and magnetic field values to a certain profile bin.

The energy resolution of the projected profile depends on the horizontal spatial resolution, which can be computed as the product of the camera sensor pixel size and the inverse of the optical magnification. Using the thin-lens equation, the inverse of the magnification can be written as [

10]

where

,

, and

are, respectively, the distances from the lens to the object, from the lens to the image on the camera sensor, and from the object to the sensor;

and

are, respectively, the sizes of the object and of the image on the sensor; and

f is the focal length of the lens. The magnification is one of the most important parameters in the design of a spectrometer setup. As will be described below, usually a compromise has to be found between a high magnification value, which provides a better resolution, and a low value, which guarantees that the entire beam spot is acquired.

Section 2 of this paper describes the design of three spectrometer setups for the beam energy measurements to be performed at the EuPRAXIA@SPARC_LAB accelerator [

11].

Section 3 reports similar design evaluations, which were carried out for the spectrometer installed in the SSRIP linac. The last section of this paper describes the characterization, in terms of resolution and magnification, of the optical system that will be used at SSRIP to acquire the transverse beam spots visible on the viewing screen. This optics system is also foreseen to be used at EuPRAXIA@SPARC_LAB.

2. Design of Beam Energy Measurements for EuPRAXIA@SPARC_LAB

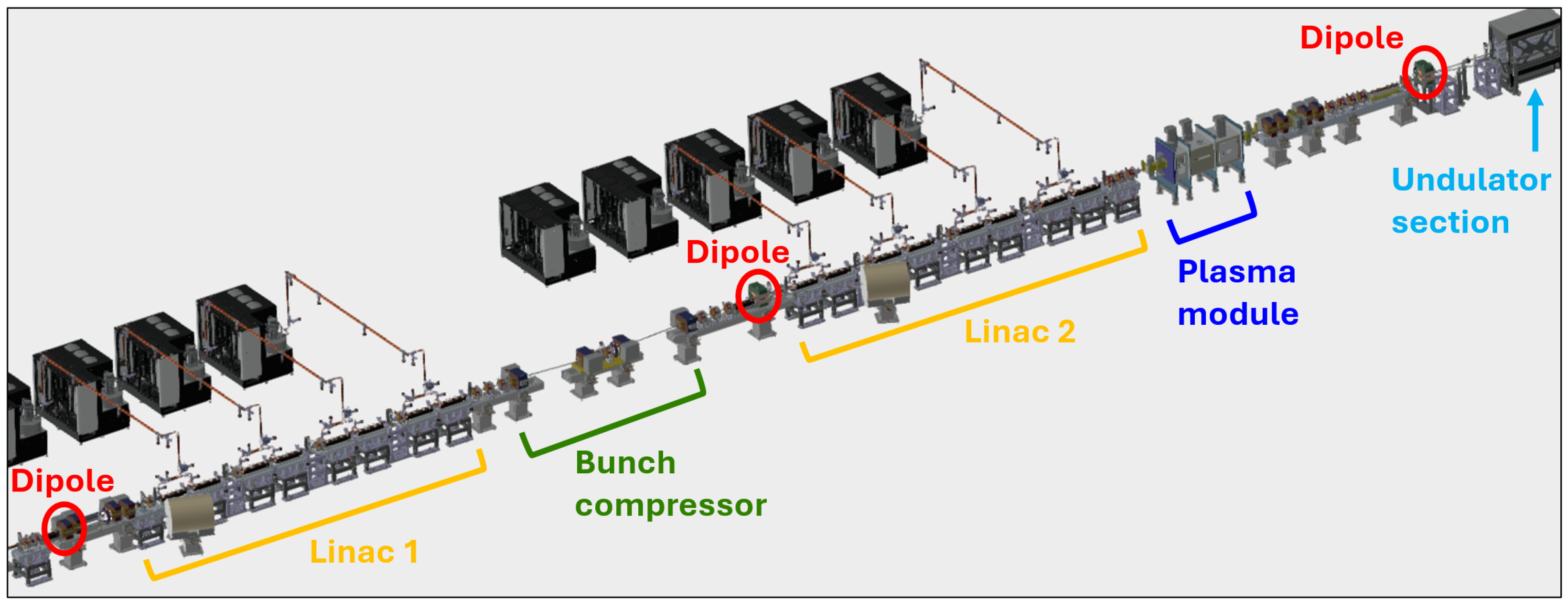

Three spectrometers will be installed along the beamline to perform energy measurements at different stages of the acceleration process (

Figure 1): downstream of the photoinjector and before the low-energy X-band linac (beam energy of 120 MeV), after the bunch compressor and before the second X-band linac (400 MeV), and after the PWFA (plasma wakefield acceleration) module and before the undulator (1 GeV). The particle-driven PWFA scheme adopted at EuPRAXIA@SPARC_LAB requires that an electron (driver) bunch with a relatively high charge traverses the plasma module, leaving behind a strong electric field (plasma wave). This wakefield is able to accelerate a second electron bunch (witness), which closely follows the driver and which has a charge smaller than the driver one. After exiting the plasma module, the driver is removed from the beamline, whereas the witness continues its path towards the undulator section.

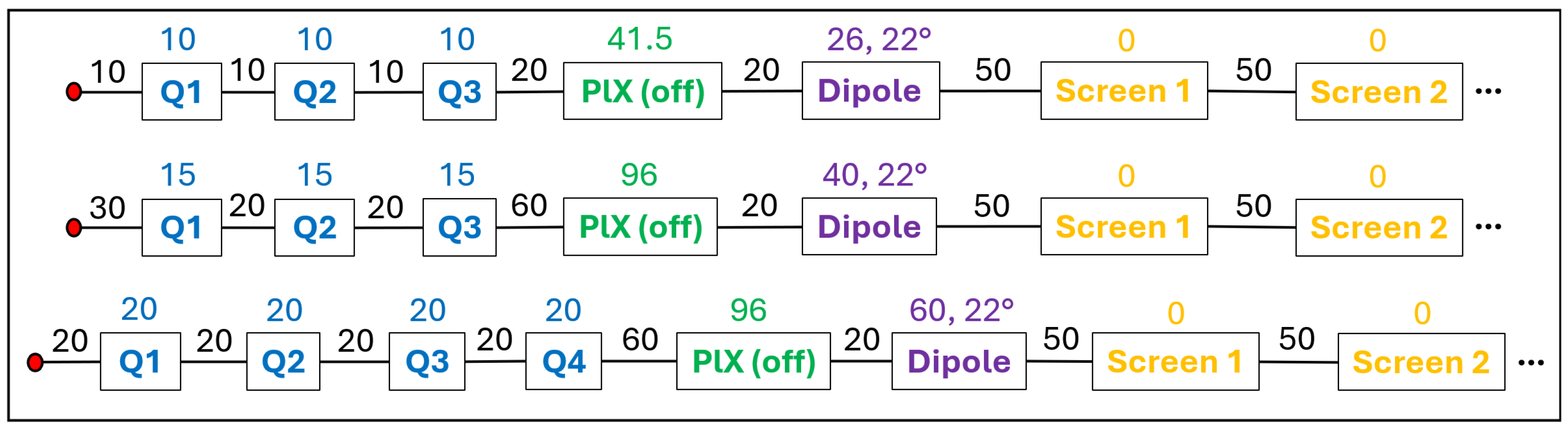

For each of the three spectrometers to be installed along the beamline, macroparticle beam dynamics simulations were performed with the Elegant code [

12] to determine the optimal distance from the dipole to the viewing screen (

Figure 2). Coherent and incoherent synchrotron radiation effects were included in the simulations, after having determined with convergence studies important numerical parameters, such as the necessary number of macroparticles to track and the number of bins needed for properly sampling the longitudinal bunch profile. The initial beam distributions, i.e., driver and witness at 120 MeV (total charge of 230 pC, full beam length of 1.0 ps,

macroparticles), driver and witness at 400 MeV (253 pC, 0.7 ps length,

macroparticles), and witness at 1 GeV (24 pC, 0.04 ps length,

macroparticles), were obtained from separate macroparticle simulations, performed with the TStep code [

13] (for the photoinjector part with space charge effects) and Elegant. The beam distribution at 400 MeV is related to an alternative working point of the accelerator, in which the driver and witness exiting from the bunch compressor are more separated in energy.

The strengths of the quadrupoles installed before each dipole were determined with the MAD-X code [

14], aiming at making the horizontal beta function

sufficiently small at the screen position. Indeed, as Equation (

4) shows [

15], in order to increase the accuracy of the rms energy measurements, the contribution of the dispersion-free term to the beam horizontal rms size

should be made negligible at the screen position:

where

and

are, respectively, the horizontal beam emittance and the relative rms momentum spread. The quantity

is the ideal beam horizontal rms size when

. As Equation (

4) indicates, the

values requested in the MAD-X simulations were such that the relative error between the actual and ideal horizontal rms sizes is below 1%. This corresponds to a dispersion-free term that is lower than 2% of the dispersion term in the expression for

.

The quadrupole strengths obtained with MAD-X were all below the limits derived by the maximum available quadrupole gradients (18 T/m at 120 MeV and 400 MeV and 30 T/m at 1 GeV). The quadrupole strength

and gradient

are related by [

16]

where

is the bending radius of the dipole and

is in units of GeV. From Equation (

5), it follows, for instance, that the maximum quadrupole strength is 9

at 1 GeV. It is important to remark that, for a given spectrometer, the quadrupole strengths obtained from MAD-X depend on the distance between the dipole and screen, since the request for a small beta function must be verified at the particular screen position. As a consequence, a different simulation had to be performed with Elegant when the dipole–screen distance was changed.

For a given beam spot at the screen, the magnification was chosen as high as possible to maximize the energy resolution, while allowing at most a negligible percentage (0.01%) of the macroparticles to be outside of the FOV. The CMOS camera installed at SSRIP for beam energy measurements (see below) is also expected to be used at EuPRAXIA@SPARC_LAB. This camera has a sensor with 1920 × 1200 pixels, a pixel size of 3.45 µm, and a sensor FOV of 6.6 mm × 4.1 mm. Therefore, the grid used in the simulation to sample the beam spot at a certain screen position was obtained by rescaling the grid of the camera sensor by the inverse of the magnification chosen.

2.1. Simulation Results at 120 MeV

In the following, the accuracy of a given simulated beam energy measurement has been computed by comparing the initial energy profile of the beam with the one reconstructed at a certain screen position. Specifically, the mean and rms energy errors between the profile at the screen and the initial one were normalized, respectively, by the mean and rms energies of the initial profile. A positive (negative) error indicates that the energy value of the profile at the target is larger (smaller) than the energy value of the starting profile. As for the resolution of the measurements, the horizontal bin size of the FOV at a given screen position was first converted into energy units by using the leftmost formula in Equation (

1); then it was normalized by the rms energy of the initial distribution. Note that the bins of a given horizontal FOV have different sizes in energy units, since the formula used for the conversion is not linear in

x. To provide a unique resolution value for a given horizontal FOV, the largest energy bin size is taken into account. Finally, the energy span covered by the horizontal FOV, again obtained by using the leftmost formula in Equation (

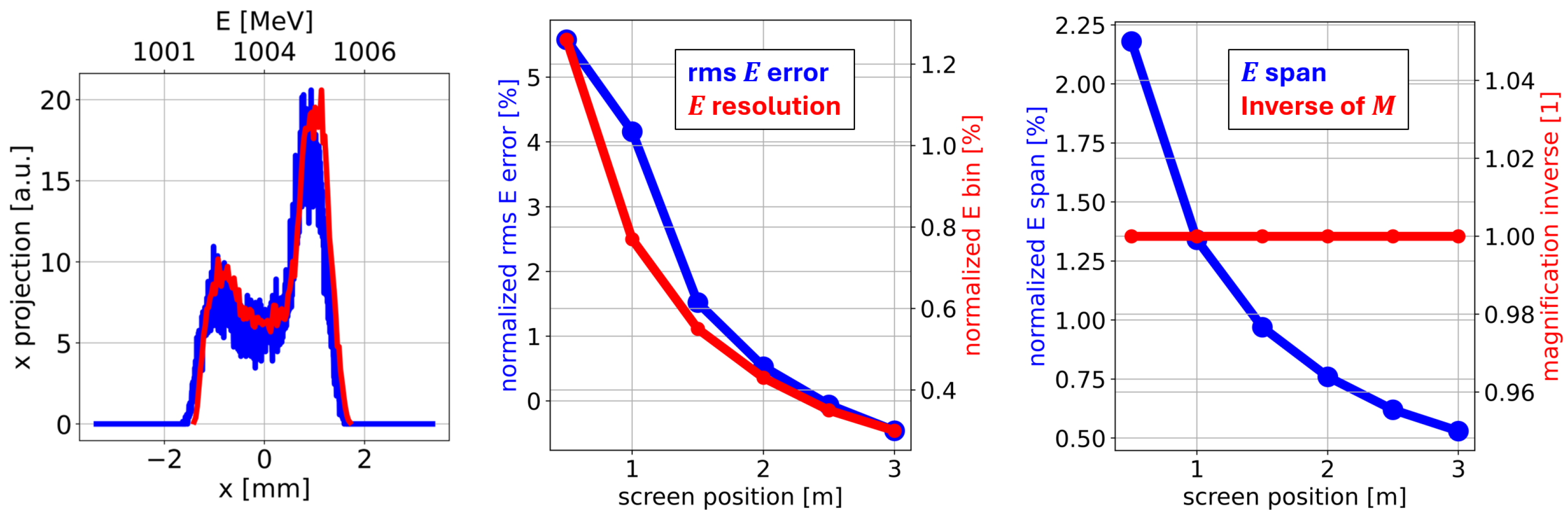

1), has been normalized by the mean energy of the initial bunch.

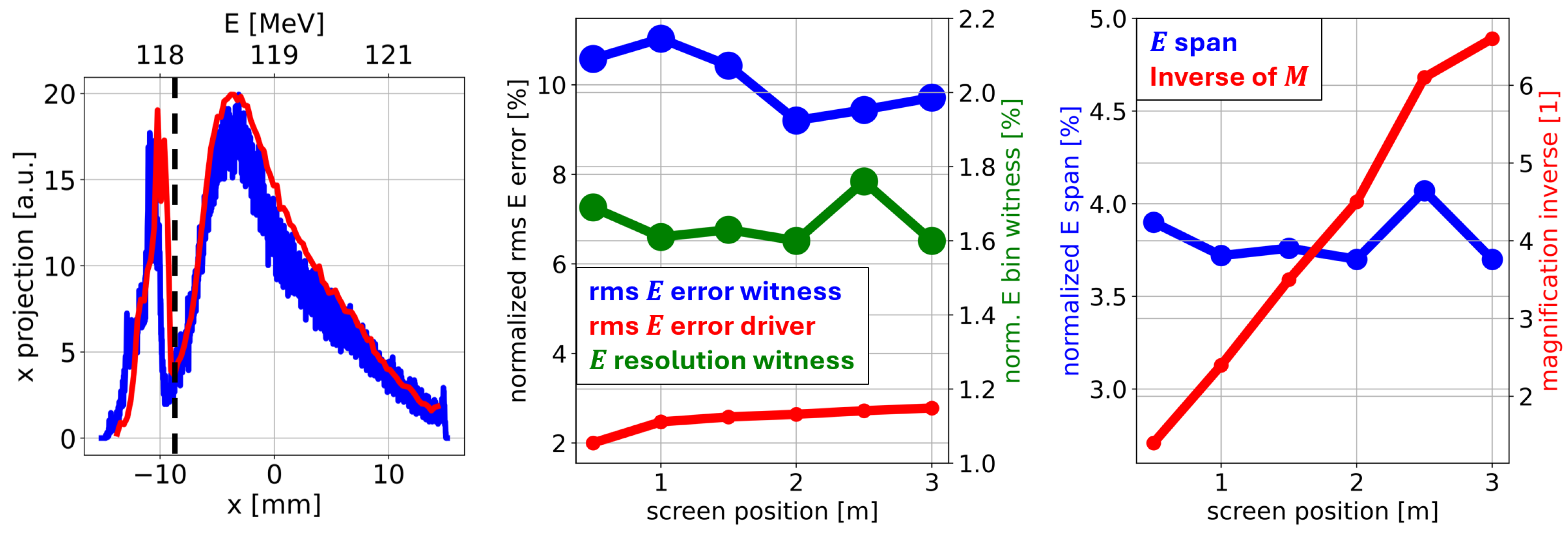

Figure 3 shows important outcomes coming from the simulations at 120 MeV. The witness and driver bunches can be distinguished on the screens, even if they are not entirely separated (

Figure 3, left). Because the driver and witness are also separated before entering the dipole due to their difference in energy (118.2 MeV and 119.7 MeV), it is therefore possible for each of these bunches to compare the mean and rms energies at a certain screen position with the corresponding value of the initial bunch. The blue and red curves in

Figure 3 (left) show that the shape of the initial beam energy profile is well retrieved with the measurement. Quantitatively, the normalized mean energy error is negligible (below 0.1%, not shown in

Figure 3), independently of the position of the screen. The relative rms energy error depends significantly on the considered bunch, and it varies by a maximum of 2% along the screen position (

Figure 3, middle). For instance, the screen placed at a 2 m distance leads to normalized rms energy errors of 9% and 3%, respectively, for the witness and driver bunches. It is important to note that these normalized rms errors are higher for the witness mostly due to its smaller initial rms energy spread (141 keV) compared to the driver one (776 keV), as the energy error without normalization is even lower for the witness (13 keV) than for the driver (21 keV).

The normalized energy bin size of about 1.7% for the witness bunch remains essentially constant when the screen position is varied (

Figure 3, middle). The normalized energy resolution of 0.3% for the driver bunch also does not significantly depend on the dipole–screen distance (not shown in

Figure 3). The better normalized energy resolution for the driver is due to its initial rms energy, which is almost six times larger than the witness one.

The fact that the energy resolution remains roughly constant when varying the screen position can be understood by examining the rightmost formula in Equation (

1) and by observing that the energy bin size decreases if the dipole–screen distance increases, assuming a constant magnification. However, if the inverse of the magnification increases linearly as a function of the screen position, then the horizontal bin size also increases linearly, and this leads to a constant energy resolution, as well as to a constant energy span of 4% (

Figure 3, right).

Note that the linear increase in the magnification inverse is due to the fact that the horizontal angular displacement of each macroparticle remains constant along the drift after the dipole. This implies that, to make the FOV follow the beam spot as it grows with the screen position, the span covered by the horizontal FOV should increase linearly with the dipole–screen distance, leading to a linear increase in the horizontal bin size.

Simulation outcomes also indicate that the macroparticle transverse displacements, from the start of the simulation up to the dipole entrance, are always lower than the radius of the smallest aperture of the accelerator lattice (i.e., the 4 mm radius of the aperture of cavity BPMs, RF PolariX units, and X-band RF cavities). This result guarantees that the entire beam is preserved during its transport up to the dipole for each considered quadrupole setup. Simulations also provide the macroparticle maximum transverse displacement along the drift from the dipole exit to the screen position. This parameter can be considered as a lower limit for the radius of the vacuum chamber to be installed after the dipole magnet, as smaller values of the radius would lead to particle losses. The maximum macroparticle transverse displacement is 4 mm when the screen–dipole distance is 0.5 m, and it increases by about 3.6 mm for every 0.5 m of additional distance (22 mm at 3 m distance).

In order to indicate the most appropriate dipole–screen distance, it should first be noted that the magnification values selected for the various screen positions lead to horizontal FOV lengths that are all compatible with typical viewing screen sizes. Indeed, the horizontal FOV length varies from 9.3 mm (magnification inverse of 1.4 at 0.5 m distance) to 43.7 mm (magnification inverse of 6.6 at 3 m distance), and the diameter of commercially available scintillation screens can reach up to 50 mm at least [

17]. Then, it should be observed that the energy resolution, span, and rms error do not change significantly with the dipole–screen distance, as the variations are all within 2%. Therefore, all the considered distances are in principle acceptable. Nevertheless, choosing a lower dipole–screen distance would provide more margin for decreasing the magnification if the beam spot is larger than the nominal or expected one. Increasing the FOV could be achieved by simply moving the camera away from the screen, which should be large enough to contain the beam. As a consequence, lower distances are preferable, provided they are feasible in terms of mechanical constraints and emitted particle radiation.

Additional simulations have been performed without including the quadrupoles to determine their impact on the accuracy and resolution of the energy measurements and also to establish their importance for the beam transport up to the screen position. For a given screen position, the chosen magnification was the one selected for the corresponding simulation with quadrupoles. Simulation results indicate that the macroparticle maximum transverse displacement increases when the quadrupoles are switched off. Considering, for instance, the 0.5 m distance, the maximum displacement from the start of the simulation up to the dipole entrance increases from 2 mm to 3 mm without the quadrupoles, although it still remains below the 4 mm radius of the smallest lattice aperture. Moreover, the maximum displacement from the dipole exit to the screen increases from 4 mm to 6 mm.

Normalized errors in mean energy remain below 0.1% when the quadrupoles are switched off. The absence of the focusing effect generated by the quadrupoles makes the percentage of macroparticles out of the FOV at the screen location increase by up to one order of magnitude, e.g., from 0.01% to 0.1% at 0.5 m. It should be noticed that these percentages are still relatively low, thanks also to the weak focusing effect provided by the rectangular dipole in both transverse planes. Without the quadrupoles, the normalized rms energy errors increase by at least 10% for the witness (53% error at 0.5 m), whereas they decrease by a maximum of 2% for the driver (1% error at 0.5 m). These outcomes indicate that it is preferable to switch the quadrupoles on during the energy measurements. Nevertheless, if the worse accuracy in the rms energy of the witness is not a concern, quadrupoles can be turned off. This would significantly simplify the setup of the measurements.

The light coming from the viewing screens can saturate for relatively high charge densities, leading to energy profile deformation and to a lower accuracy in the energy measurements. To evaluate the risk of light saturation, the maximum charge density was determined for each transverse beam spot measured at the screen. Due to the fact that the horizontal beam size increases with the dipole–screen distance, the maximum charge density decreases with the screen position. When the quadrupoles are switched on in the simulation, the maximum charge density is 58 pC/mm

2 at the 0.5 m distance and 12 pC/mm

2 at 3 m. Results do not significantly change when the quadrupoles are turned off (59 pC/mm

2 at 0.5 m and 12 pC/mm

2 at 3 m). These charge density values should not lead to light saturation, as measured saturation thresholds can be in the order of nC/mm

2 [

18,

19].

2.2. Simulation Results at 400 MeV

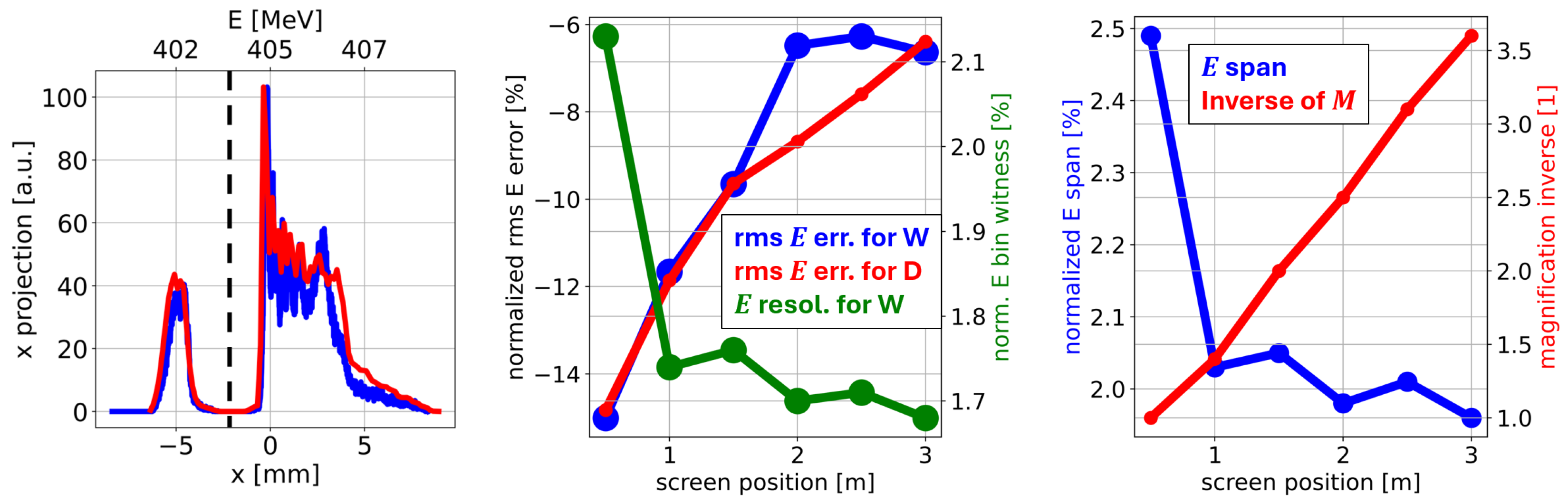

As concerns the simulations at 400 MeV, one can see from

Figure 4 (left) that the witness and driver are completely separated on the screen. For each bunch and screen position, the normalized mean energy error is below 0.1%. The accuracy of the rms energy measurements is essentially the same for the two bunches, and it improves significantly with the screen position, as the rms energy error decreases from 15% to 6% (

Figure 4, middle). Also the normalized energy resolution for the witness improves with the screen–dipole distance, although variations are small (less than 0.5%). At each screen position, the normalized energy bin size for the driver (not shown in

Figure 4) is 3.6 times lower than the one for the witness. This difference is essentially due to the larger rms energy spread of the initial driver bunch (904 keV) compared to the one of the witness (246 keV).

As observed above, the linear increase in the magnification inverse as a function of the dipole–screen distance follows from the intention of having at each screen position the smallest possible FOV that contains the entire beam spot. In fact, the lowest possible magnification of 1 selected for the screen position of 0.5 m leads to a FOV that is still relatively large for the beam spot. Quantitatively, computing the horizontal size of the entire beam (driver plus witness) as the full width at 3% of the beam profile maximum, the horizontal filling factor of the beam spot relative to the FOV horizontal span is 65% for the 0.5 m distance, whereas it is between 79% and 82% for the other screen positions. The non-optimal FOV at the distance of 0.5 m leads to a slightly worse energy resolution (

Figure 4, middle).

Simulation outcomes also indicate that the macroparticle maximum transverse displacement, from the start of the simulation up to the dipole entrance, is always lower than the 4 mm radius of the smallest lattice aperture. The maximum displacement after the dipole is 3 mm when the screen–dipole distance is 0.5 m, and it increases by about 2 mm for every 0.5 m of additional distance (13 mm at 3 m distance).

Analyzing the results shown in

Figure 4, it can be inferred that placing the screen at 2 m from the dipole exit is a valid choice, since the rms energy error (6% for witness and 9% for driver), the energy bin size (1.7% for witness and 0.5% for driver), and the magnification inverse of 2.5 would be relatively low. The energy span would be 2%, which is sufficient to deal with beam mean energy jitters estimated at 0.2%.

Turning off the quadrupoles in the simulation does not lead to a significant increase in the macroparticle maximum transverse displacement. Considering, for instance, a dipole–screen distance of 2 m, the maximum transverse displacement from the simulation starting point to the dipole entrance remains below 2 mm, whereas the one from the dipole exit to the screen position is still 9 mm. In addition, the absence of the quadrupoles does not lead to an important increase in the number of macroparticles outside of the FOV at the different screen positions. In part, this is due to the weak focusing effect provided by the sector dipole in the bending plane, as this focusing is already able to make the horizontal beta function negligible at the various screen positions. Even if without the quadrupoles the vertical beta function increases along the simulated part of the accelerator, the vertical beam size remains relatively small; e.g., the rms is 0.4 mm at 3 m from the dipole exit.

With the quadrupoles switched off in the simulation, the normalized mean energy errors always remain below 0.1%, whereas the rms energy errors for the driver and witness increase by up to 6% for the screen positions above 1 m. For instance, the rms energy error for the witness increases from 6% to 12% at a 2 m distance. These simulation outcomes suggest that quadrupoles should be kept on during the measurements. Nevertheless, allowing just a few percent decrease in the rms energy accuracy, good results can still be obtained without the quadrupoles.

The maximum charge density at the screen decreases from 153 pC/mm2 (at the 0.5 m distance) to 44 pC/mm2 (at 3 m) if the quadrupoles are turned on in the simulation. The maximum charge density varies instead from 121 pC/mm2 (at 0.5 m) to 36 pC/mm2 (at 3 m) when the quadrupoles are switched off. These charge density values, even though larger than the corresponding ones obtained at 120 MeV, are still below 1 nC/mm2, and therefore they should not lead to light saturation.

2.3. Simulation Results at 1 GeV

Results from the simulated beam energy measurements at 1 GeV show that the energy profiles obtained at the different screen positions match well the initial energy profile (

Figure 5, left). Even selecting a magnification of 1 at each screen position (

Figure 5, right), the horizontal filling factor of the beam spot relative to the FOV span remains relatively small. The filling factor at a 0.5 m distance is just 17%, and it increases up to 67% at a 3 m distance. Since a better energy resolution is obtained with a larger filling factor, the normalized energy bin size decreases with the dipole–screen distance, varying from 1.3% to 0.3% (

Figure 5, middle).

The relative mean energy error is below 0.1% at each screen position. The normalized rms energy error decreases with the dipole–screen distance, going from 5.6% to −0.5% (

Figure 5, middle). It is interesting to remark that this monotonic behavior of the rms error is only due to coherent synchrotron radiation, since if the latter is turned off in the simulation, then the rms error remains essentially constant (

) when the screen position is varied. Note that the change in beam energy spread induced by synchrotron radiation in general also depends on the transverse distribution entering the dipole [

20]. This explains how at 1 GeV the different beam distributions (one per screen position) entering the dipole make the (common) longitudinal distribution interact in different ways with the coherent synchrotron radiation inside the dipole magnet.

Results from simulations show that the macroparticle maximum transverse displacement, from the start of the simulation up to the dipole entrance, is lower than 4 mm. The maximum displacement after the dipole is 1.2 mm when the screen–dipole distance is 0.5 m, and it increases by about 0.3 mm for every 0.5 m of additional distance (2.6 mm at 3 m distance).

The simulation outcomes shown in

Figure 5 indicate that positioning the screen at a 2.5 m distance from the dipole exit is a valid choice at 1 GeV, since the energy rms error and bin size would be −0.1% and 0.4%, respectively. However, a magnification of 1 would lead to a normalized energy span of only 0.6% (

Figure 5, right), which is too small to contain the estimated mean energy jitter at the exit of the plasma module. Indeed, dedicated particle-tracking simulations and statistical studies have shown that the beam mean energy after the plasma module can vary within a normalized energy span of 6%. Increasing the magnification inverse from 1 to 9.6 for the 2.5 m distance, the desired energy span of 6% is obtained, at the expense of increasing the energy bin size to 3.6%. The rms energy error would still remain at −0.1%.

Switching off the four quadrupoles in the simulation, the increase in the macroparticle maximum transverse displacement is not negligible. Taking into account, for instance, the 2.5 m distance, the largest transverse displacement from the simulation starting point to the dipole entrance becomes 2 mm, which is nevertheless still lower than the 4 mm limit. The maximum displacement from the dipole exit to the screen position increases from 2 mm to 4 mm.

Without the quadrupoles, the percentage of macroparticles outside of the FOV increases strongly with the screen position, reaching 2% and 5% at the screen–dipole distances of 2.5 m and 3 m, respectively. The horizontal beam size is always lower than the FOV horizontal size, thanks to a waist in the horizontal beta function occurring even before the dipole, which makes the beta function negligible at the different screen positions. This waist is produced by eight permanent quadrupoles positioned between the plasma module and the separator chicane, which are needed to match the beam transverse distribution to the lattice of the downstream undulator. The weak focusing effect of the sector dipole in the bending plane is negligible compared to the focusing effect of the permanent quadrupoles. The macroparticles outside of the FOV are therefore due to an increase in the vertical beta function along the simulated part of the accelerator, which leads to a significant growth in the vertical beam size.

The relative mean energy errors remain below 0.1% without the quadrupoles, whereas the rms energy errors become 2% for the screen positions up to 2.5 m. The rms error is slightly different (1%) at the 3 m distance due to the significant percentage of macroparticles out of the FOV. From these simulation results, it follows that the four quadrupoles should be switched on during the measurements, at least to confine the beam in the vertical plane.

The maximum charge density at the screen reduces from 19 pC/mm2 (at 0.5 m) to 9 pC/mm2 (at 3 m) when the quadrupoles are turned on. The maximum charge density varies instead from 11 pC/mm2 (at 0.5 m) to 4 pC/mm2 (at 3 m) without the quadrupoles. These charge density values are not expected to lead to light saturation, as they are at least two orders of magnitude lower than the measured threshold of 1 nC/mm2.

For each spectrometer setup taken into account,

Table 1 reports the recommended screen position and the values of the most important parameters that characterize the energy measurement. The reported data assume that the driver and witness are measured at the same time on the screen and that the quadrupoles needed to have a negligible horizontal beta function at the screen are switched on in the simulations. The last column of

Table 1 emphasizes the main differences in results that are obtained when the quadrupoles are turned off.

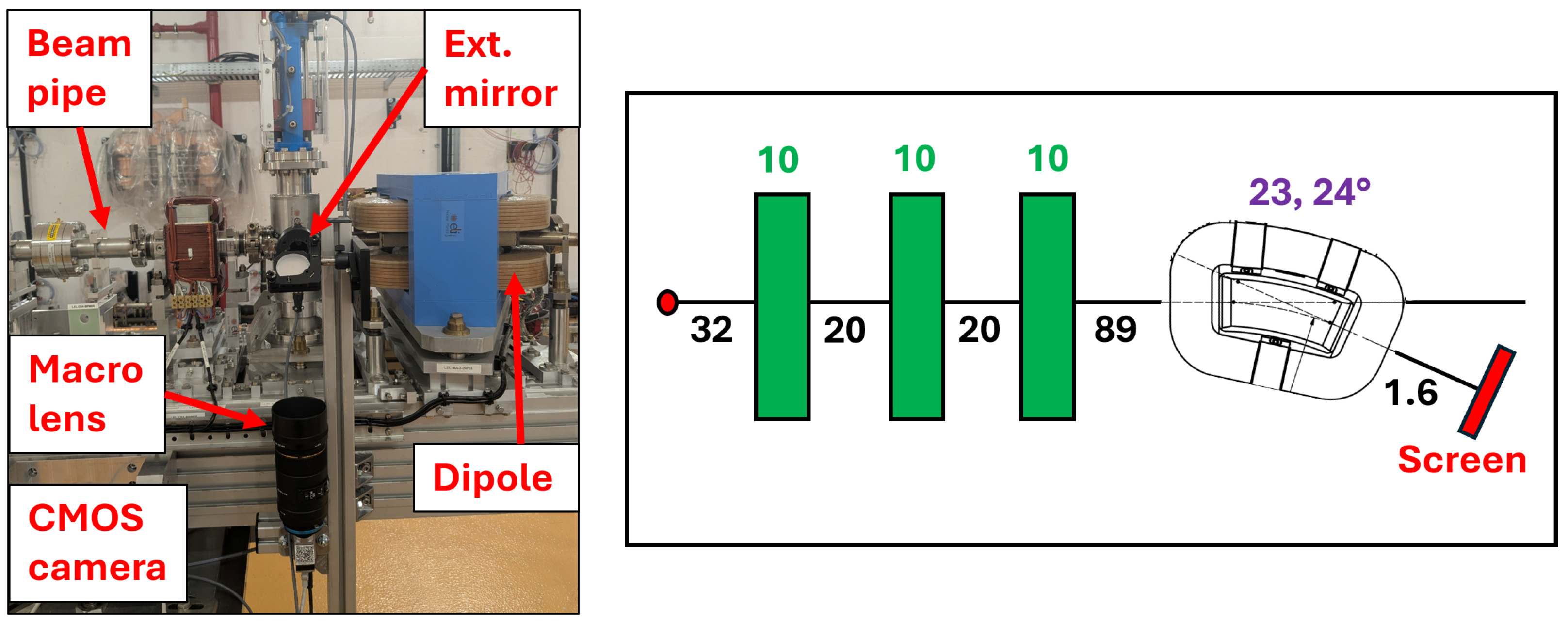

3. Design of Beam Energy Measurements for SSRIP

The SSRIP linac will operate at a repetition frequency of 10 Hz in single-bunch mode. The charge of the electron bunch will be 100 pC and the beam will be accelerated to the nominal energy of 100 MeV. The SSRIP linac is mainly composed of an RF gun, two S-band and one C-band RF structures, and a sector dipole (

Figure 6, left), where the beam either goes straight to the physics experiments or is bent towards a viewing screen for beam energy measurements.

In order to estimate the accuracy and resolution of these energy measurements, macroparticle simulations including synchrotron radiation effects were performed with the Elegant code. Simulations started after the C-band RF structure and before the first matching quadrupole, specifically at 11 m from the cathode of the RF gun (

Figure 6, right). The initial bunch distribution (100 pC, bunch length of 12.5 ps,

macroparticles) was obtained from a separate simulation performed with the ASTRA code [

21], which included space charge effects. In the ASTRA simulation, it was possible to reach the desired 100 MeV only with the two S-band cavities. The C-band structure will be needed, for instance, to reach 140 MeV, which is the maximum beam energy that the spectrometer can measure, which corresponds to a maximum magnetic field of 0.84 T.

The macroparticle tracking in Elegant ended at the viewing screen positioned at 1.6 m from the dipole exit (

Figure 6, right). It should be added that the simulation starting point coincides with the position of an additional diagnostic station able to provide the transverse spot of the beam as soon as the latter exits the last accelerating RF cavity. During the energy measurements, it will therefore be possible to compare the simulated and measured transverse beam spots at three important accelerator locations: between the C-band structure and the first matching quadrupole, just before the dipole magnet, and at the screen positioned after the dipole. These comparisons will help in benchmarking measurements and simulations.

The strengths of the three quadrupoles installed before the dipole were determined with the MAD-X code, with the goal of making the horizontal beta function negligible at the screen position, so that the condition expressed on the rightmost side of Equation (

4) was satisfied. The obtained strengths were all within the limits imposed by the maximum available quadrupole gradient of 18 T/m. A camera sensor with 1920 × 1200 pixels, and a pixel size of 3.45 µm, was assumed in the simulations, as the installed CMOS cameras have these features (see below).

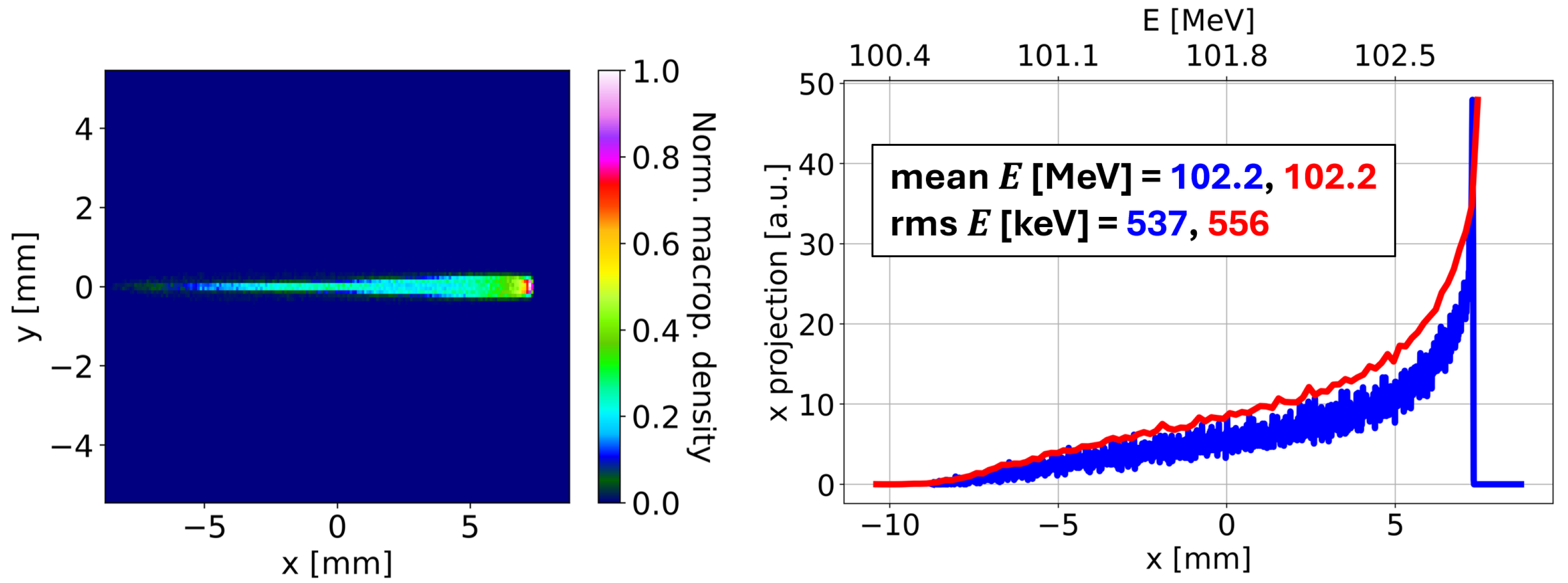

Simulation Results

Figure 7 (left) shows the FOV with the transverse beam spot at the screen position, assuming a magnification inverse of 2.6. The installed circular YAG screen, which has a diameter of 25.4 mm, would entirely contain this FOV, as it has a size of 17.2 mm × 10.8 mm. The chosen magnification leads to a relatively large (82%) horizontal filling factor of the beam spot relative to the FOV horizontal span. At the same time, with this magnification only a negligible fraction (0.01%) of the macroparticles are out of the FOV.

By projecting the FOV on the horizontal axis, one can see that the energy profile at the screen is close to the one obtained from the initial bunch distribution (

Figure 7, right). The normalized mean and rms energy errors are just 0.01% and 3%, respectively. The chosen magnification defines the normalized energy resolution of 0.2% and also the relative energy span covered by the FOV, which is 2%. The mean of the initial energy profile has been used as the normalization factor for the energy mean error and span, whereas the energy resolution and rms error have been normalized by the rms energy of the input bunch distribution.

Simulation results also revealed that the amplitude of the maximum transverse oscillation of the macroparticles along the simulated part of the accelerator is 7 mm up to the dipole and 21 mm after it. These amplitudes are lower than, and therefore compatible with, the corresponding smallest apertures of the lattice, which are 24 mm and 35 mm before and after the dipole, respectively. The minimum aperture of the lattice, which coincides with the diameter of the vacuum chamber, is higher after the dipole to take into account the larger horizontal beam size caused by the dispersion.

The simulation outcomes reported above indicate that the spectrometer installed at SSRIP works as desired. Moreover, essentially the same results were found in the simulation by turning off the three quadrupoles while keeping the same magnification at the viewing screen. Indeed, without the quadrupoles the horizontal filling factor of the beam increases by just 3%, whereas all the other figures of merit, which include the number of macroparticles outside of the FOV, the energy accuracy, and resolution, remain the same.

The missing focusing of the three quadrupoles is still guaranteed by the weak focusing effect of the sector dipole, which makes the horizontal beta function negligible at the screen position. Indeed, even if without the quadrupoles the beta value at the screen increases by a factor of six, also because the waist in the beta function moves from 1.6 m to 1.4 m with respect to the dipole exit, the dispersion contribution to the horizontal beam size at the screen remains three orders of magnitude higher than the dispersion-free contribution. With the quadrupoles switched off, the vertical beam size rises along the simulated part of the accelerator. However, this increase is not a concern, as the vertical full beam size at the screen is 6 mm, which is lower than the length of the vertical FOV. Therefore, switching off the quadrupoles will preserve the quality of the beam energy measurements, and at the same time it will significantly simplify the measurement setup.

The maximum charge density at the screen was evaluated. The values are 20 pC/mm2 and 8 pC/mm2, respectively, when the three quadrupoles are turned on and off. These charge densities are two orders of magnitude lower than the measured threshold of 1 nC/mm2, so light saturation should not occur.

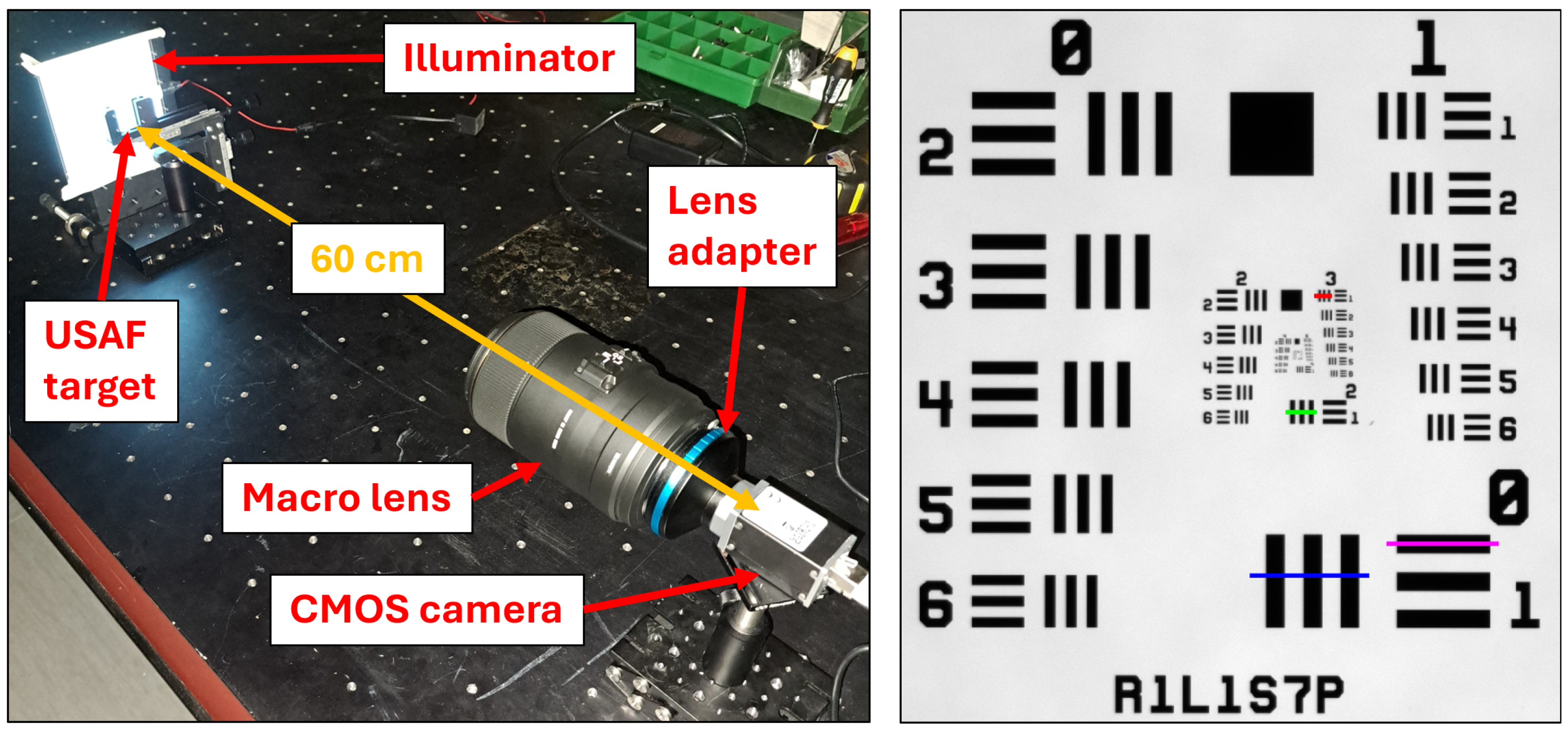

4. Characterization of the CMOS Camera–Macro Lens Optics System

Measurements were performed to characterize the resolution and magnification of the optics system installed at SSRIP and also foreseen to be used at EuPRAXIA@SPARC_LAB to acquire the transverse beam spots for energy monitoring. The optics system (

Figure 8, left) is composed of a CMOS camera (Basler a2A1920-51gmBAS [

22]), a lens adapter (Fotodiox Pro Nik(G)-C [

23]), and a macro lens (SIGMA 105 mm F2.8 EX DG MACRO OS [

24]), and its performance was tested by using a resolution test target (1951 USAF 1” × 1” [

25]) back-lit by an electroluminescent illuminator providing uniform light (VEA [

26]).

The camera sensor has 1920 × 1200 pixels, with a pixel size of

µm. Different sensor–target distances were considered, from 50 cm to 130 cm. For each measurement, the exposure time of the sensor (from 25 ms to 39 ms) was chosen to exploit the entire brightness range (12 bits), without reaching saturation. The Basler pylon Viewer software [

27] was used to set the acquisition parameters of the camera and also to save the images onto the hard-drive (

Figure 8, right), which were then analyzed with Matlab [

28] to evaluate the resolution and magnification of the optics system.

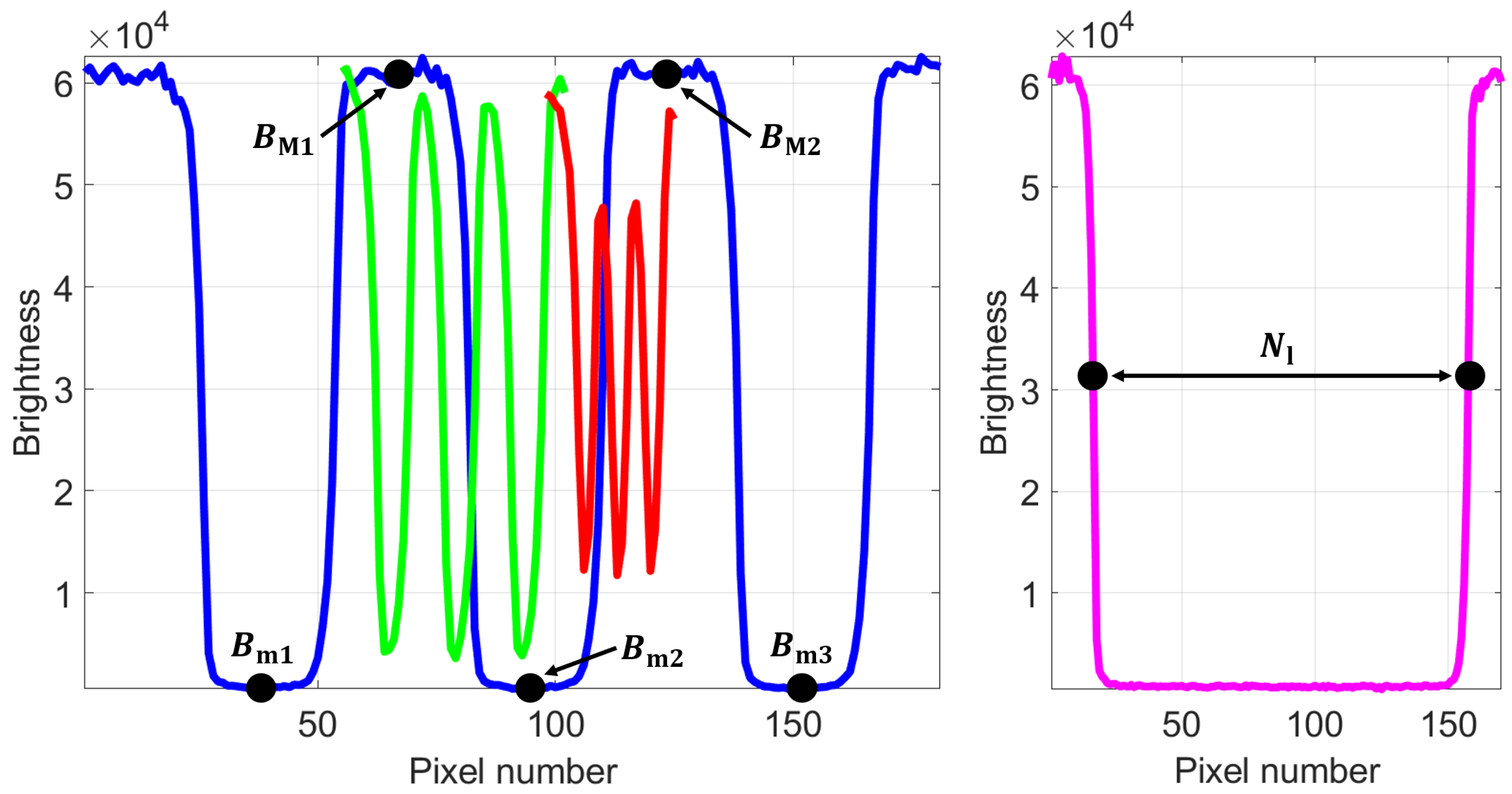

For each sensor–target distance, the resolution was determined by pixel profiling triplets of black line segments belonging to different groups and elements of the USAF target (

Figure 9, left) [

25,

29,

30]. The lines of a given triplet (black or white) have the same thickness

W, which corresponds to the design resolution

(Equation (

6)). Note that both triplets of an element have the same

, and usually it is sufficient to use only one of them for the evaluations. For a certain triplet, to determine the degree to which the sensor can distinguish the different lines, or equivalently to evaluate the contrast for a given design resolution, the Michelson contrast

(Equation (

6)) [

31] was computed for each of the four pairs of consecutive minima–maxima (

−

, etc.) of the brightness curve (

Figure 9, left). Then, an average of the four calculated contrasts was taken to provide just one contrast value for a certain design resolution. The expressions for

and

(for one pair) are [

25,

31]

where

G and

E represent, respectively, the group and element numbers. In Equation (

6), the design resolution

is also expressed in the units of line pairs per millimeter, which are often used in optics.

The expression for the Michelson contrast in Equation (

6) assumes a value between zero and one. As expected, the contrast is zero when the minimum and maximum brightnesses coincide. The value is one (highest contrast) when the minimum brightness is zero, regardless of the value of the maximum brightness. Dividing both the numerator and denominator by two in the expression for

, one can see how the Michelson contrast coincides with the brightness curve half-amplitude, normalized by the average value of the curve. For instance, the three curves in

Figure 9 (left) have roughly the save average value, but the blue curve has the largest half-amplitude, so the Michelson contrast related to it will be the highest. It should be noted that the minimum and maximum brightness values used to evaluate

are derived by multiplying the actual acquired values by 16 (see the caption of

Figure 9). This multiplication does not alter the contrast value, as the constant appears in both the numerator and denominator of

. One should also mention that other definitions of contrast exist (e.g., Weber, RMS, and Haziness [

32]); however the Michelson one is commonly used for brightness curves that are essentially periodic, such as the ones obtained by analyzing the line triplets of an USAF target.

As well as providing the actual resolution of the camera–lens system, the measurements performed with the USAF target allowed us to determine the magnification of the optics system. For a given camera–lens pair, the magnification depends only on the distance between the target and the camera sensor (see also Equation (

3)). As described above, the magnification is one of the most important parameters to consider for the design of beam energy measurements with a magnetic spectrometer. Macroparticle simulations can provide the optimal values for the magnification; therefore during the energy measurements it becomes essential to know the distance between the camera and the viewing screen, which provides a given magnification. The inverse of the latter was evaluated by dividing the known length

of a line segment by the product of

and the number of pixels

covered by the same line segment:

As reported in Equation (

7), and as can be seen from

Figure 8 (right), the length of a line segment is equal to its width (or design resolution) multiplied by five. Note that

is an integer; therefore the

pixels cannot in general cover exactly the line segment taken into account. This introduces an error which in relative terms decreases with

. For this reason, one of the segments belonging to the element 1 of group 0 was chosen to evaluate the magnification, as the length of this segment (2.5 mm) is the largest (

Figure 8, right). As a cross-check, one side of the USAF target (25.4 mm long) was also used to determine the magnification, which indeed should not depend on the considered line segment. This second evaluation was possible only for sensor–target distances above or equal to 90 cm, as the sides of the USAF target are not entirely visible at lower distances.

Measurement Results

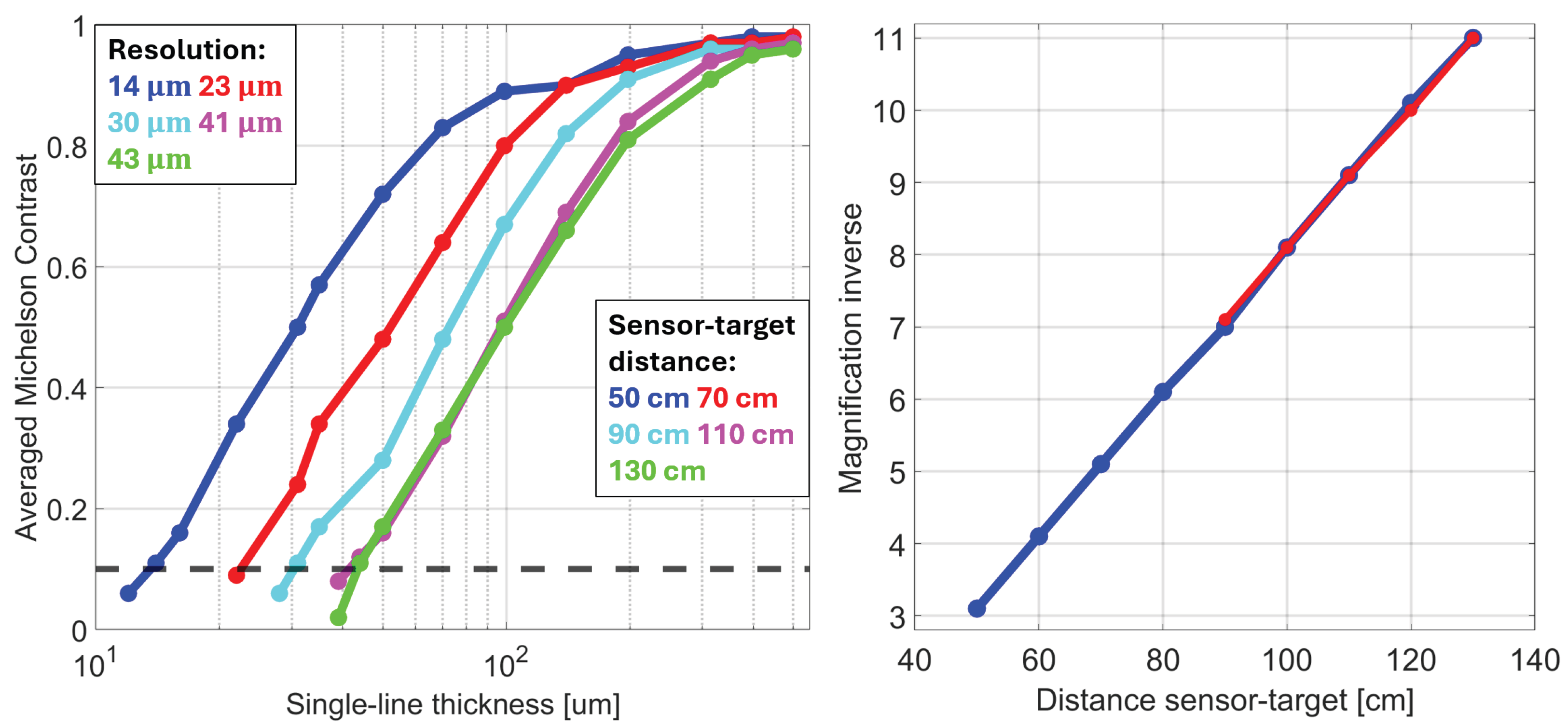

Figure 10 (left) shows the average Michelson contrast as a function of the design resolution for five distances between the USAF target and the camera sensor. As expected, for a given distance the contrast increases with the single-line thickness, going from zero to one in a non-linear relationship. Moreover, for a certain contrast value, the resolution worsens with the sensor–target distance, again in a non-linear way. To determine the actual resolution of the camera–lens system, the reference contrast value of 0.1 has been chosen. Although this choice is rather arbitrary, a Michelson contrast of 10% is often adopted as a reference when estimating the resolution of an optics system either with an USAF target [

29,

30,

33] or with other methods [

34,

35,

36]. With the contrast set to 0.1, the resolution of the camera–lens pair varies from 14 µm at a 50 cm distance to 43 µm at 130 cm (

Figure 10, left).

The dependence of the magnification inverse on the sensor–target distance is shown in

Figure 10 (right). This dependence is linear, as anticipated by Equation (

3). The slope of the curve is about 0.1/cm; therefore the estimated focal length is 10 cm, which indeed corresponds to the design focal length of the lens (10.5 cm). The plot shows a good agreement in results when either the largest line segment of the USAF target or one side of the target itself is taken into account for the magnification evaluation. Extrapolating the obtained results, the maximum magnification of 1 provided by the lens is obtained when the sensor–target distance is 30 cm.

One should observe that the nominal resolution of the optical system, which is given by the product of the sensor pixel size (3.45 µm) and the magnification inverse (

Figure 10, right), worsens with the sensor–target distance. This is expected, as a higher distance implies a larger FOV (or smaller magnification), with the consequence that a given pixel of the camera sensor covers a wider portion of the target. Note that the nominal resolution improves with the numerical aperture (NA) [

37] of the optical system, since the NA increases for a lower distance between the lens and the target.

It is important to evaluate the difference between the measured and nominal resolutions for a given sensor–target distance. Indeed, due to imperfections in the optical system (camera and lens) used to acquire the images, the measured resolution is usually worse than the nominal one. For instance, at the 50 cm distance, the measured resolution is 13.60 µm (

Figure 10, left), whereas the nominal resolution is 10.69 µm, taking into account the measured magnification inverse of 3.1 (

Figure 10, right). Therefore, the difference in resolution, normalized by the nominal one, is 27%. By repeating the calculation for the other considered distances, one can see that the normalized difference in resolution varies between 14% (at 130 cm) and 32% (at 110 cm). These percentages can change if another contrast value is used as the reference to evaluate the measured resolution.

Further studies are required to evaluate the impact of the measured contrast values on the simulated transverse beam spot at the screen. This will allow us to determine the influence of the blurring effect generated by the optics system on the accuracy of the energy measurements. It should be noted that simply resampling a projected horizontal profile with a measured resolution is not correct, as the blurring effect modifies the shape of the profile without affecting the nominal resolution. Moreover, the contrast value assumed as the reference for resampling should be properly justified.

5. Conclusions

Macroparticle beam dynamics simulations have been performed to design the beam energy measurements that will be carried out at EuPRAXIA@SPARC_LAB. In particular, simulations significantly helped in determining the optimal position of the viewing screen by providing important figures of merit, such as energy resolution, accuracy, and span.

For all the analyzed setups, simulations indicate that the accuracy in mean energy is excellent, as the relative errors are less than 0.1%. At 120 MeV, the possibility of measuring the driver and witness at the same time on the screen significantly simplifies the measurement setup. The analysis shows that the distance between the screen and the dipole magnet should be as low as possible. Positioning the screen at 0.5 m from the dipole exit, the error in rms energy is 11% for the witness and 2% for the driver. The obtained energy span of 4% is relatively large. Switching the quadrupoles off in the simulation, the rms energy error for the witness increases to 53%, and the number of macroparticles outside of the FOV rises to 0.1%.

At 400 MeV, the witness and driver can again be measured at the same time on the screen. Placing the latter at 2 m from the dipole exit is the recommended setup, which leads to an rms energy error of 6% for the witness and 9% for the driver. The energy span of 2% is sufficient to deal with the estimated beam mean energy jitters. When the quadrupoles are turned off, the rms energy error for the witness increases to 12%.

The recommended dipole–screen distance is 2.5 m at 1 GeV. This setup provides an rms energy error of just 0.1%. However, the expected jitter in mean energy necessitates a significant decrease in magnification, so that the required energy span of 6% is achieved. The lower magnification leads to a worse energy resolution of 4%, even if the rms energy error remains equal to 0.1%. Switching the four quadrupoles off in the simulation, the percentage of macroparticles outside of the FOV increases to 2% due to the missing focusing in the vertical plane. Also the rms energy error grows to 2%.

Macroparticle simulations were also carried out to estimate the accuracy and resolution of the beam energy measurements that will be performed at SSRIP. Simulation results indicate that the installed spectrometer will lead to accurate and well-resolved measurements. Indeed, the error in mean energy is negligible, and the energy rms error and resolution are only 3% and 0.2%, respectively. Thanks to the weak focusing effect provided by the dipole, turning off the quadrupoles in the simulation leads essentially to the same outcomes. Therefore, quadrupoles can be switched off, resulting in a significant simplification of the measurement setup.

Optics measurements have been performed to characterize the resolution and the magnification of the camera–lens system that will be used at SSRIP, and likely also at EuPRAXIA@SPARC_LAB, to acquire the transverse beam spots during the energy measurements. Selecting a Michelson contrast of 10% as the reference, the measured resolution is larger than the nominal one by up to 35% for each sensor–target distance taken into account. As expected, the inverse of the magnification increases linearly as a function of the sensor–target distance, and it grows by one unit every 10 cm. A resolution of 14 µm and a magnification inverse of 3 are obtained at the distance of 50 cm. Further studies are required to quantify the impact of the measured contrast values on the mean and rms of the energy profiles acquired at the screen.