In this section, details regarding the layout and design choices for the TRCFFC are provided, and the differences between conventionally machined and additively manufactured collectors are discussed. The comparisons are supported by simulations and measurements of the TRCFFC’s RF properties. The final design is compared to a RCFFC measuring an Ar10+ particle beam at the GSI linear accelerator UNILAC measured in the beamline X2.

2.1. Tapered Radially Coupled FFC Design Considerations and Simulations

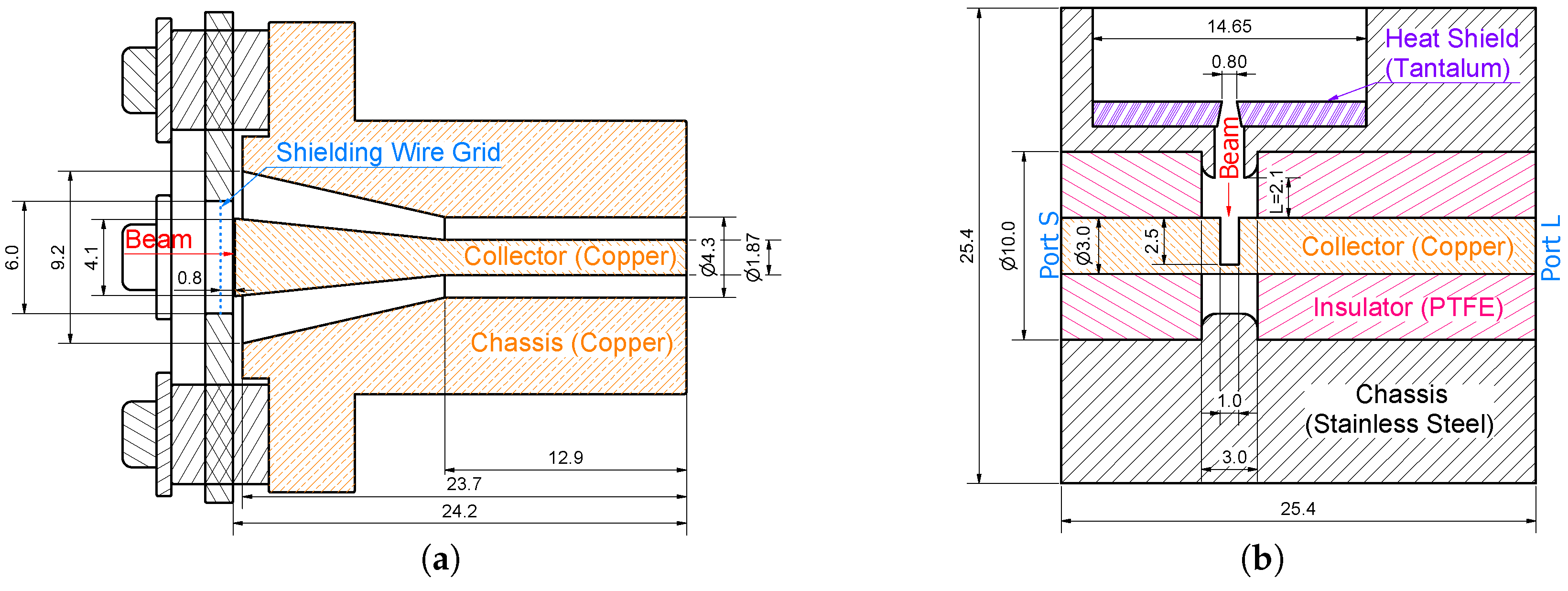

A new variant of the previously discussed RCFFC has been developed for UNILAC at GSI. The optimization objectives are defined as achieving a higher signal-to-noise ratio and enhancing the geometric suppression of SEs for bunch lengths between 100 ps to 400 ps at velocities ranging from 5% to 15% of the speed of light. The new design is shown in

Figure 6. The diameter of the pinhole in the heat shield has been increased from

to

. Comparing different pinhole sizes, a theoretical signal gain of 5.1 is achievable for a uniform distribution. This gain is determined by the ratio of the pinhole areas in the two designs. The projected gain is reduced when considering the Gaussian profile of the transversal bunch shape. If the transversal profile is a strong ellipsoid, we can estimate the gain

by

where erf is the Gauss error function and

the dominant transversal beam size effectively reducing it to a 1D estimation. This estimation will be met if, e.g., the beam in

x-plane is significantly larger than in

y-plane. Assuming a dominant transversal beam size of

, the actual gain is approximately a factor of 2.19. If the beam is symmetric in both planes, the estimation of

should be done by comparing the integrated charge density limited by the radii of the heat shield pin holes using Equation (

7). Using the same example values as for the 1D estimation, the gain for a symmetrical beam would be a factor 4.86.

The drift passage width of inside the chassis directly after the heat shield pinhole is larger than the pinhole itself, ensuring that entering particles reach the drill hole in the collector without prematurely hitting the drift passage walls. Consequently, the collector drill hole also needs to have a larger diameter ( ) than the drift passage width to prevent generation of secondaries at the surface of the collector aside inside the drill hole.

The number of SEs leaving can be controlled by the depth-to-aperture ratio of the drill hole [

7]. This ratio is 2.5 for the RCFFC design. A minimum drill hole depth of

is needed to reach at least the same depth-to-aperture ratio for a drill hole diameter of

. However, at these values,

% of the leaving SEs will not be separated from the ion-induced signal for

. Thus, a drill hole depth of 8 mm was chosen, with the last 2 mm featuring a

cone-shaped end. This cone-shaped termination of the drill hole facilitates the redirection of SEE toward the hole walls, as described by Equations (

3) and (

4). A study of various Faraday cup geometries has been performed in [

9], enabling the assessment of the effect of different drill hole terminations such as flat or wide and narrow cone-shaped on SE suppression. While a flat-ended drill hole results in a main direction of the SEs backward out of the hole, the cone-shaped tips considerably increases SE absorption at the hole walls as can be seen by comparing the results of

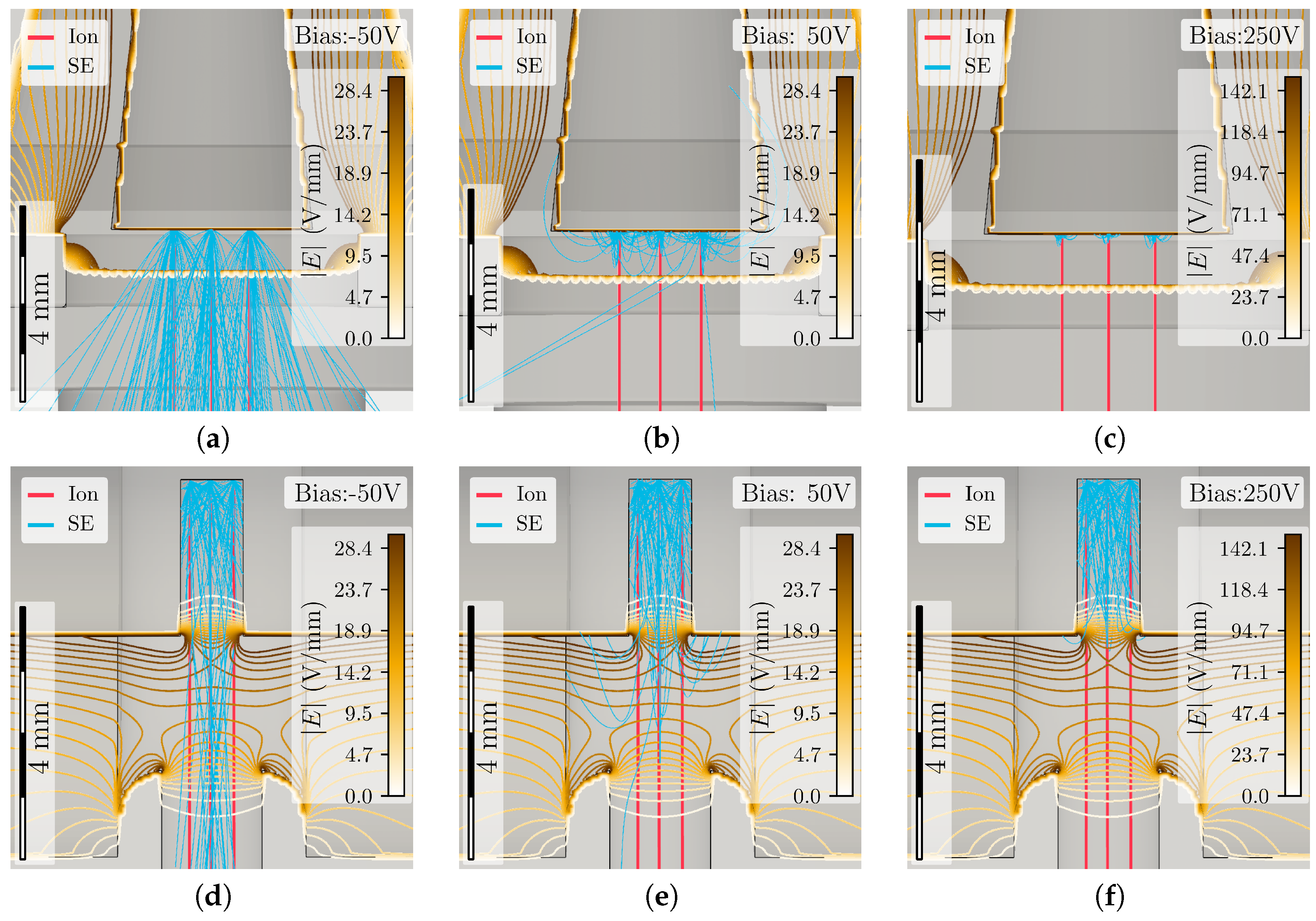

Figure 3 (bottom) with

Figure 7. Despite of the five instead of three ions, the number of SEs escaping the geometrical suppression is even lower for the TRCFFC than the RCFFC, while the quality of the bias field remains similar.

A more detailed analysis with respect to the angle of the cone shape has been performed in [

7]. It was found that a flat-tip design allows approximately 20% of the total SEs to escape, whereas a cone-shaped tip with a 56° angle reduces this to a minimum of 3.3%. Applied to the present design featuring a 60° cone, it is expected that approximately 2.4% of all the emitted primary SEs will escape the drilled hole. Of these, 96% are anticipated to be temporally separated from the ion peak due to their travel time through the drill hole.

The penetration depth

of the ions has been estimated using SRIM [

22] for typical energies at the GSI linear accelerator UNILAC ranging from 1.4 MeV/u to 11.4 MeV/u [

23] for a wide variety of ion species from

to

238U in copper. The results indicate that for uranium, the penetration depth is

μm and for hydrogen

μm. Accordingly, it is expected that any ion species will be stopped within 100 μm. The total thickness of the collector sums up to 10 mm. The collector length is kept to a reasonable size of 50 mm to ensure that it fits into the diagnostic ports of the GSI linear accelerator UNILAC while keeping a safe distance to other diagnostics. An SMA connector with a pin diameter of

mm was employed to extract the signal from the FFC. The entire length of 25 mm was utilized for tapering to the smaller diameter to achieve improved impedance matching.

The central diameter of the tapered collector is thicker than the outer diameter of the SMA connector, making it impossible to insert the collector through the openings for the SMA connectors in the chassis of the TRCFFC. In the simulations, the surface currents are observed to flow directly from the center toward the connectors. The split-block technique [

24,

25] is utilized, in which the chassis is divided into two halves along a plane perpendicular to the SMA ports and passing through the drift passage. SMA connectors with loose inner pins are employed, allowing the chassis and the connector’s insulator to be soldered to the collector prior to final assembly. Since the SMA pins are loose and not fixed inside the connector, they can rotate, which may cause misalignment between the collector’s drill hole and the pinhole of the heat shield. This would compromise the geometrical SE suppression. While the collector is radially limited in its movement by the SMA pins, glass pins are added (see

Figure 6) to lock the rotation and ensure a well-defined longitudinal position of the collector inside the chassis. Quartz glass was selected for the pins for its high heat resistance, low thermal expansion coefficients, mechanical stability, and the low permittivity

. It has been ensured that the 50 Ω geometry is present at any point inside the TRCFFC from center of the collector down the full taper till the SMA connectors. Only at the positions of the glass pins, the 50 Ω geometry is lowered to about 46 Ω. The position of the glass pins has been optimized to minimize the disturbance of the signal. The effect of the glass pins on the S-parameter is discussed later in

Section 2.3. A second critical point in terms of impedance matching is the change in vacuum to the PTFE insulator at the crossing of the SMA connector and the TRCFFC. The outer diameter of the chassis is wider by 0.06 mm and the diameter of the collector is bigger by

mm, creating a small geometrical step, which can cause minor reflections. Since we did not observe reflections at this geometrical step in the PIC simulations above the noise level, we evaluated the performance of the impedance matching solely based on the S-parameters.

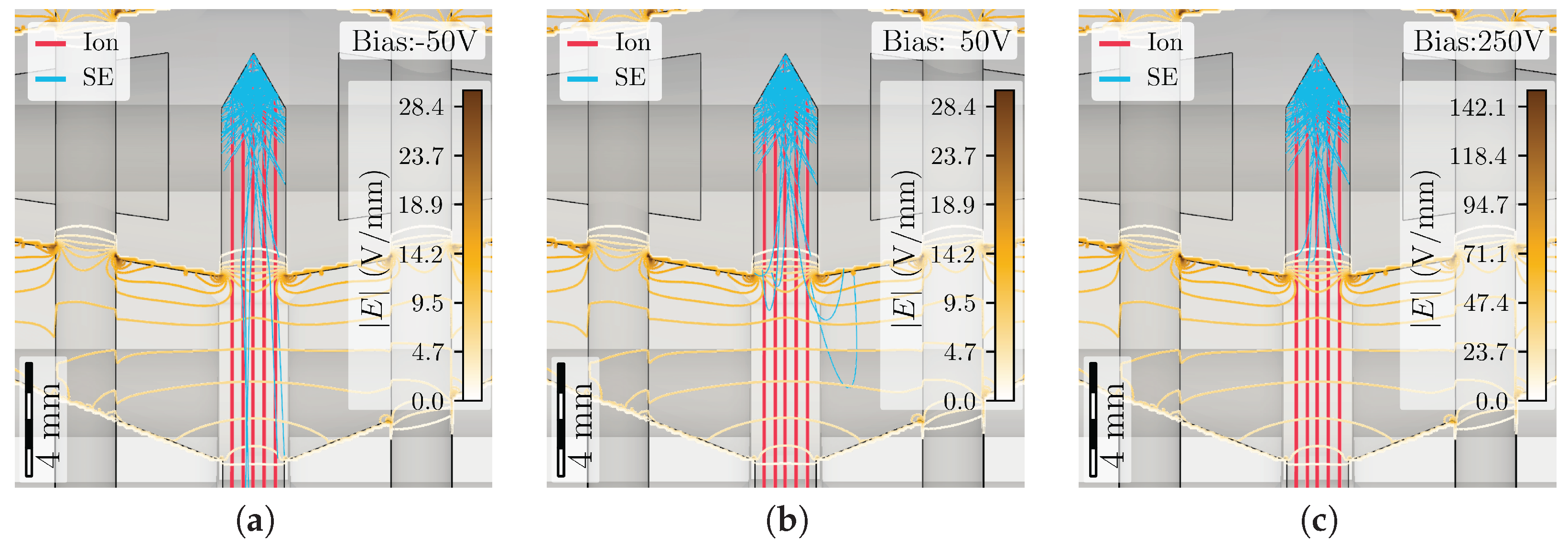

The effect on SE suppression using the optimized TRCFFC design is shown in

Figure 8. The same beam parameters are used as in the simulations for

Figure 2 and

Figure 4. Only SEs through impinging ions on the collector are allowed. No significant signal strength gain is observed despite the larger pinhole in the heat shield, because all the emitted ions hit the collector in all the simulations, never touching any other surface before. Hence, the same number of ions is collected in each case. In the new design, the geometrical SE suppression reduces the amplitude of the SE signal from

μV (unbiased RCFFC) down to 0.22 μV. Additionally, the increased separation time minimizes the overlap between the ion and the SE signal down to 300 ps. The amplitude error due to the overlapping SEs drops below 1 μV. The total impact of the SEs on the ion signal is sufficiently low, making it likely that low-charge-state ion beams (

) will not require an additional bias scheme to suppress SE-induced signals to the noise level.

2.2. Construction of a Additively Manufactured Tapered Radially Coupled FFC

The key feature of the TRCFFC is its deep drilled hole in the inner collector, which ensures high geometrical suppression of SEs, as demonstrated in the simulations (see

Section 2.1). As a consequence of this deep drill hole, the collector needs to be tapered down to the diameter of the inner pin of the connector used. Accordingly, the most critical construction constraints are the taper angle of the collector, the cone in the chassis matching the 50 Ω geometry, and the through-holes for the glass pins for alignment. To evaluate the potential of additive manufacturing for beam diagnostics in heavy ion beam research, such as at GSI, several collectors in slightly varying geometries were fabricated using additive manufacturing techniques. These were compared to conventionally machined collectors with respect to their RF properties. The collectors were additively manufactured (AM) at Fraunhofer-Institut für Werkstoff- und Strahltechnik IWS using electrolytic tough pitch copper (Cu-ETP) with a purity of

% in a TruPrint1000 Green Edition, which operates with a green laser of 515 nm and a maximal power of 500 W. The collectors were additively manufractured vertically from port to port. There was no need for support structures because the taper angle is sufficiently small.

Figure 9a shows the first batch produced still attached on the build plate. This batch was additively manufractured without any waiting times, resulting in a strong coloration on the bottom side indicating overheating due to insufficient heat extraction through the build plate. The third batch (see

Figure 9b) was additively manufractured with waiting times after each layer resulting in a three-time-higher build time. The decoloring was strongly reduced with only a small part closely below the collector hole being still decolored.

The collector hole and the holes for the glass pins were directly taken into account during the printing process. Since no support structures were used inside the drill holes, they became slightly oval. It was necessary to post-process the through-holes for the alignment glass pins and the holes for the SMA pins. The AM copper material is relatively soft, allowing manual drilling. A few fractals at the edges of the holes needed to be removed as well. The surface had not been polished. The cleaned collectors may be seen in

Figure 10. One of the very first designs was meant to utilize a flat tap connection SMA pin. This would have been advantageous in preventing the rotating of the collector even without glass pins. However, the slit was too thin to be AM. Moreover, soldering the flat tab to the collector needs a different assembly approach than the split-block technique. Therefore, the round post SMA connector was selected, with the disturbance introduced by the glass pins to the 50 Ω geometry being accepted. There were three different versions of the collector additively manufactured in each batch: one without holes, one with 2 mm, and one with 3 mm holes for glass pins. The different versions were used to study the influence of the glass on the RF properties (see

Section 2.3).

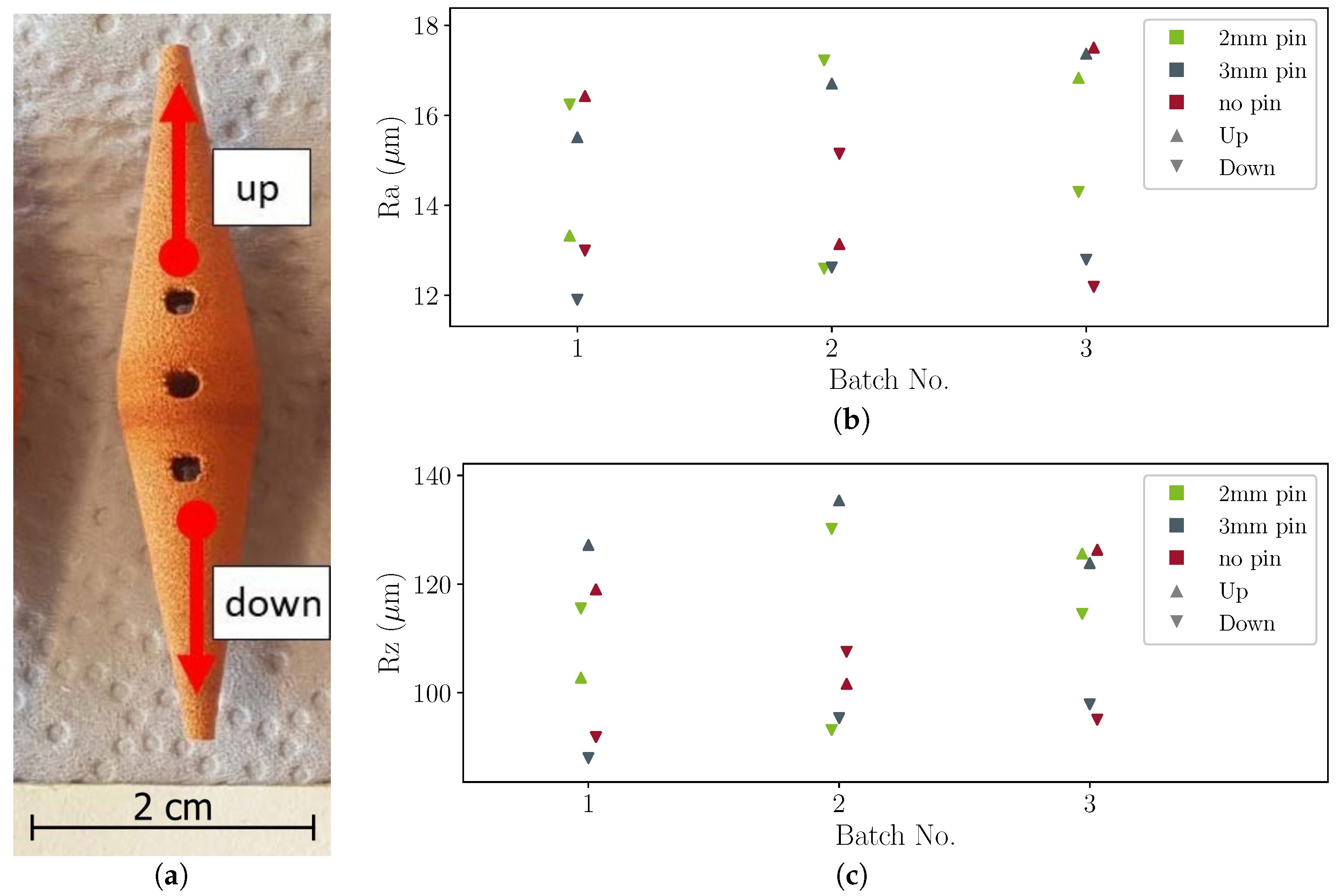

The surface roughness was measured using a Surfcom Touch 50 [

26]. The probe diameter was 5 μm and the measurement was performed once for the upper cone and once for the lower cone of the collector for a distance of 8 mm, as shown in

Figure 11a. The average profile height deviations from the mean line

,

(see Equation (

8)) [

27], are shown in

Figure 11a.

The roughness ranges from 12 μm to 18 μm, with the topside being rougher than the lower part according to

. Also, the maximum peak height to valley height

(see Equation (

9),

Figure 11c) [

27] indicates higher roughness on the upper side. Overall, the roughness of the 50 Ω geometry varies by

%, which is negligible.

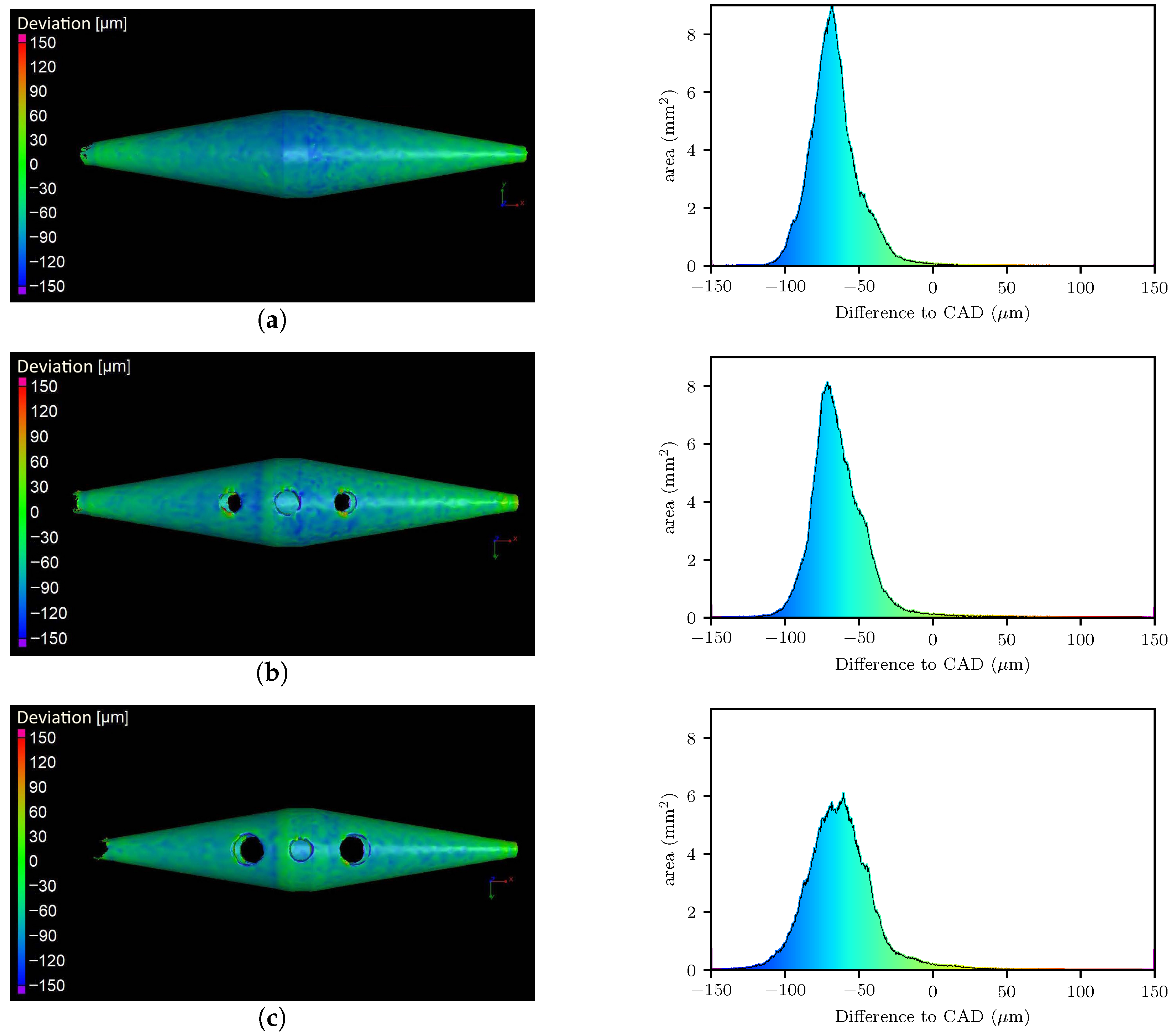

The deviation from the CAD model was measured using a GOM ATOS Core 135 and is shown in

Figure 12. One challenge of additive manufacturing is the shrinkage of the body, which depends on the geometry and is difficult to predict. In our case, the shrinkage was about −20 μm to −100 μm, with the most common difference of

μm. This led to an error of 0.24% to 1.2% and most common

%. In future iterations, the collector geometries are planned to be additively manufractured with radii increased by approximately 50 μm to compensate for shrinkage, thereby reducing dimensional deviations and minimizing the impact on the 50 Ω geometry.

Another aspect of the surface roughness

is its significant influence on the SEY. For random surfaces, the SEY first increases for

and decreases afterwards steadily with higher

, as can be observed in Figure 10 of [

28] for

. Another study demonstrated that sputtering the surfaces with gold decreases the SEY, as shown in Figure 7 of [

29] for a surface roughness

of 0.25 μm to 1.5 μm. Since our surface roughness is higher by an order of magnitude, it remains unclear whether these results are directly applicable. The model of the reduction in the SEY described in [

28,

29] implies that produced SEs are recaptured in the valleys of the rough surfaces and thus do not contribute to the globally measured SEY. Hence, deeper valleys might be beneficial. Future work should also clarify whether these results transfer to very rough random surfaces. If so, additively manufacturing the chassis of the TRCFFC should reduce tertiary electrons, which are produced by electrons escaping the applied bias and finally hitting the chassis.

2.3. RF Characterization of the Radially Coupled FFC Designs

During the melting process in laser powder bed fusion (LPBF), small defects can occur, leading to porosity formation. The conductivity

of the AM material is affected by this porosity, which adds up to other factors such as surface roughness and material impurity [

30,

31]. Additionally, the skin effect

(Equation (

10)) is affected, which plays a significant role in high frequency signal losses within conductors.

with the frequency

f, the free space permeability

, the relative permeability

, and the electrical conductivity

. For low-power lasers (e.g., 370 W), the conductivity of fused copper has been measured at approximately 58% to 73% of the international annealed copper standard (IACS) [

30]. When high-power lasers (>500 W) are employed, conductivities of up to 94% [

31] have been achieved. With a green laser, even an electrical conductivity of 100 IACS in the as-built condition is achievable [

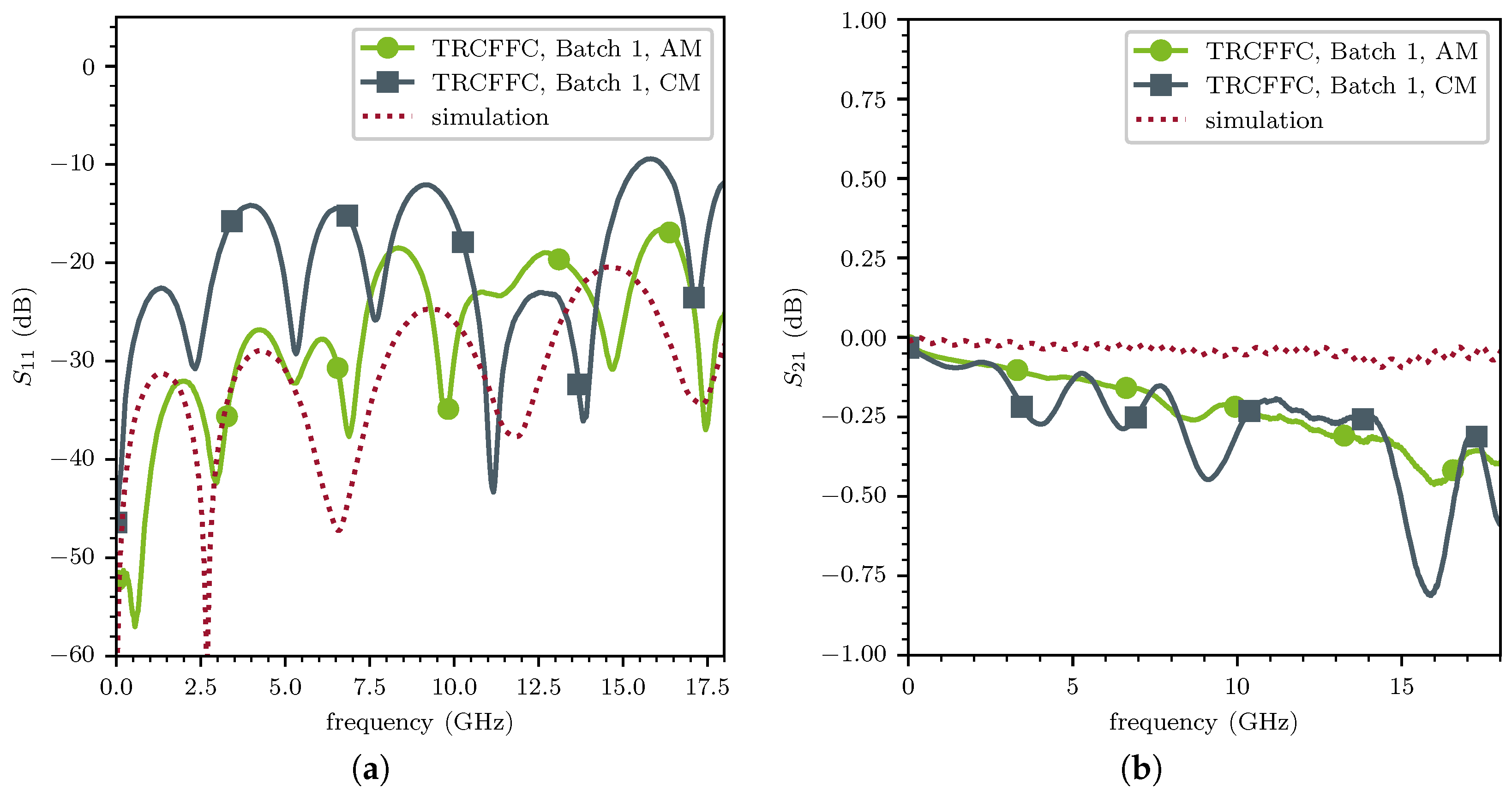

32]. Therefore, the RF properties of the TRCFFC are analyzed using both a conventionally machined (CM) and an AM collector. The primary figure of merit for the RF characterization are the S-parameters and the analysis of the temporal resolution, which was also compared to those obtained for the RCFFC. In

Figure 13, the measured S-parameters for a CM and an AM collector are shown in comparison with the CST simulation results. These collectors have no holes for glass pins to study the differences in roughness and precision of the geometry apart from geometrically induced resonances. A FieldFox N9917A [

33] with

phase-stable SMA SUCOFLEX 126E cables [

34] was used. The calibration was performed with a Keysight Ecal Module N7554A [

35]. It is observed that the reflections (

Figure 13a) are lower across nearly the entire 18

range, with the AM collector performing better, on average, by about

dB. Additionally, for the transmission (

Figure 13b), there was improved performance across the entire measurement range, with an average of

dB. The deviation from the CAD model was measured using a VR-6000 [

36] for both the traditionally machined and additively manufactured version seen in

Figure 14. The measured profile were arranged to minimize the mean difference from the CAD model, resulting in smaller deviations compared to the previous full 3D scan in

Figure 12. The mean difference for the AM version is 13

and 37

for the conventionally machined one. The surface roughness

of

of the CM collector is significantly smoother, but still, the geometrical differences are stronger than the differences in the roughness. Hence, the performance difference with respect to the S-parameter is dominated by the geometrical differences rather than the surface roughness.

In our case, the additively manufactured collectors exhibited geometrical deviations smaller than the conventionally machined ones, which was also reflected by the RF performance measurements. Therefore, we focused on these additively manufactured collectors to study the influence of the glass pins. Three different kinds of collectors were constructed, as shown in

Figure 9: one without, one with 2 mm, and one with 3 mm holes for glass pins. The measurement results were compared with CST simulations across the full 18

bandwidth of the SMA connectors (see

Figure 15). The best results were obtained without any glass nor holes for glass pins, as seen in

Figure 15a. Adding 2 mm diameter holes to the collector did not affect the S-parameters up to

as seen in

Figure 15b. However, the transmission was reduced above

to a minimum of

dB at

and the reflections increased up to

dB. Frequencies above

are, therefore, considered to be outside the bandwidth of the TRCFFC. After inserting 2 mm glass pins into the alignment hole, the S-parameters remained close to the previous results up to

(see

Figure 15c). The transmission decreased for higher frequencies. The usage of the glass led to two absorption peaks at 14

and

. Increasing the diameter of the glass pins to 3 mm (see

Figure 15d) leveled the reflection to

dB till 6

and quickly increased to

dB afterwards. The absorption caused by the thicker glass pins drastically broadened the absorption peak at

with a transmission of only

dB. Therefore, the use of glass should be minimized to lower the disturbance of the 50 Ω geometry still stabilizing the collector position in the tapered coaxial design. From the perspective of the S-parameters, this TRCFFC design with 2 mm glass pins could be used for bunches with a

.

Concerning the coaxial design, the TRCFFC can be operated easily up to 7

, but the distance between the collector surface and the inner surface of the chassis also limits the usable bandwidth. The pre-field of the bunch advances ahead of the actual charges, prematurely reaching the collector and inducing a signal. This effect can be included into the calculation of the theoretical measurable bunch length

estimated by Equation (

11) under the assumption that the diameter of the drill hole inside the collector and the drift tube after the heat shield is small compared to the distance

L between the collector and the inner chassis surface [

7]:

where

is the extension of the actual bunch length

and can be calculated from

with a geometrical constant

[

37] and the velocity

of the bunch. To evaluate this effect, a series of simulations with very short bunches at different velocities was performed. The resulting simulated signal of these very short bunches was equivalent to the impulse response of the FFCs. In

Table 1, the resulting bunch length

of simulations for different bunch velocities

are shown next to the actual emitted bunch length

and the calculation of

. Thereby, we used the relation of the full width at half maximum

to derive the bunch length from the output signal of the TRCFFC.

Table 2 shows the results for the same simulation settings for the RCFFC. The temporal resolution

is calculated from the emitted bunch length

and output signal

by

. The generation of SEs on the collector was activated to observe the effects of insufficient suppression, which led to longer measured bunches. The bias voltage was set to 0 V. In both tables, it is evident that the time of flight of the particles through the gap between the chassis and the collector is the dominant parameter for very short pulses (10

). The higher

, the lower is the impact of

, and hence, the precision of the FFC rises. In comparison to the RCFFC, the temporal resolution of the TRCFFC should be lower by a factor of 2.95 with respect to the theoretical model

. Examining the simulation results, the factor between the temporal resolution of both designs is estimated to a factor of 2.54. Increasing the diameter of the collector for the TRCFFC to improve the SE suppression results in a trade-off, as it comes at the cost of a lower bandwidth. However, as the bunch length increases, the deviation in the TRCFFC simulations for estimating the bunch length

at

becomes less than 10% for bunch widths

exceeding

. For 400 ps, the deviation remains below 1% even without bias potential. The higher bandwidth of the RCFFC geometry results in a higher temporal resolution also for shorter bunches resulting in a lower deviation, e.g.,

% for

at

. Without an appropriate bias scheme, bunch shapes of

are elongated. The lower temporal separation

of the RCFFC leads to an overlapping of the electron and ion signal resulting in a deviation of

% from the actual simulated bunch length. The finite temporal resolution at speed of light is

for the RCFFC and

for the TRCFFC.

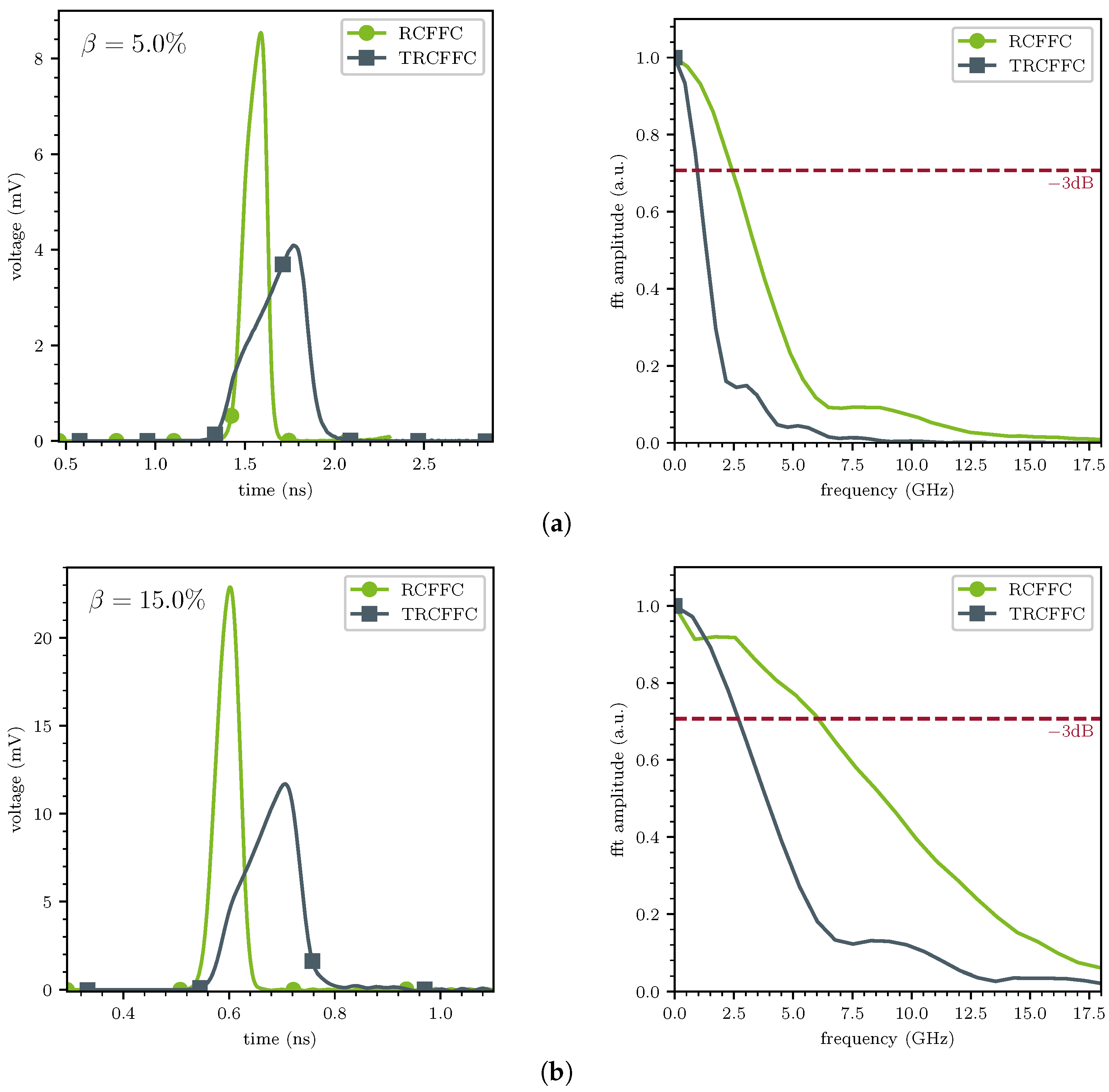

A second way to assess the temporal resolution is to estimate the

dB bandwidth of the FFCs. To do this, we simulated a very short pulse below the temporal resolution of the FFCs as shown in

Figure 16 (left). For the desired design goal velocities, the lower bound was 5% and the upper one was 15%, which allowed us to obtain the impulse response of the systems. Then, we calculated the FFT of these signals (see

Figure 16 right). The intersections of this amplitude signal with the level 0.707 is equivalent to

dB degradation in signal power. The bandwidth of the RCFFC at

(see

Figure 16a) is

(TRCFFC

), and in the case of

, the bandwidth is

(TRCFFC

), which corresponds to a factor of 2.5 to 2.25 between the bandwidths of both devices. This is in line with the evaluation of the FWHM width estimation precision for very short bunches of 2.45 to 2.56 for the same velocity range, as discussed earlier in this section. Both methods for examining the temporal resolution capabilities show that radially coupled FFCs are beam velocity-dependent. Hence, they must be tailored to their use case in both expected velocities and bunch lengths.

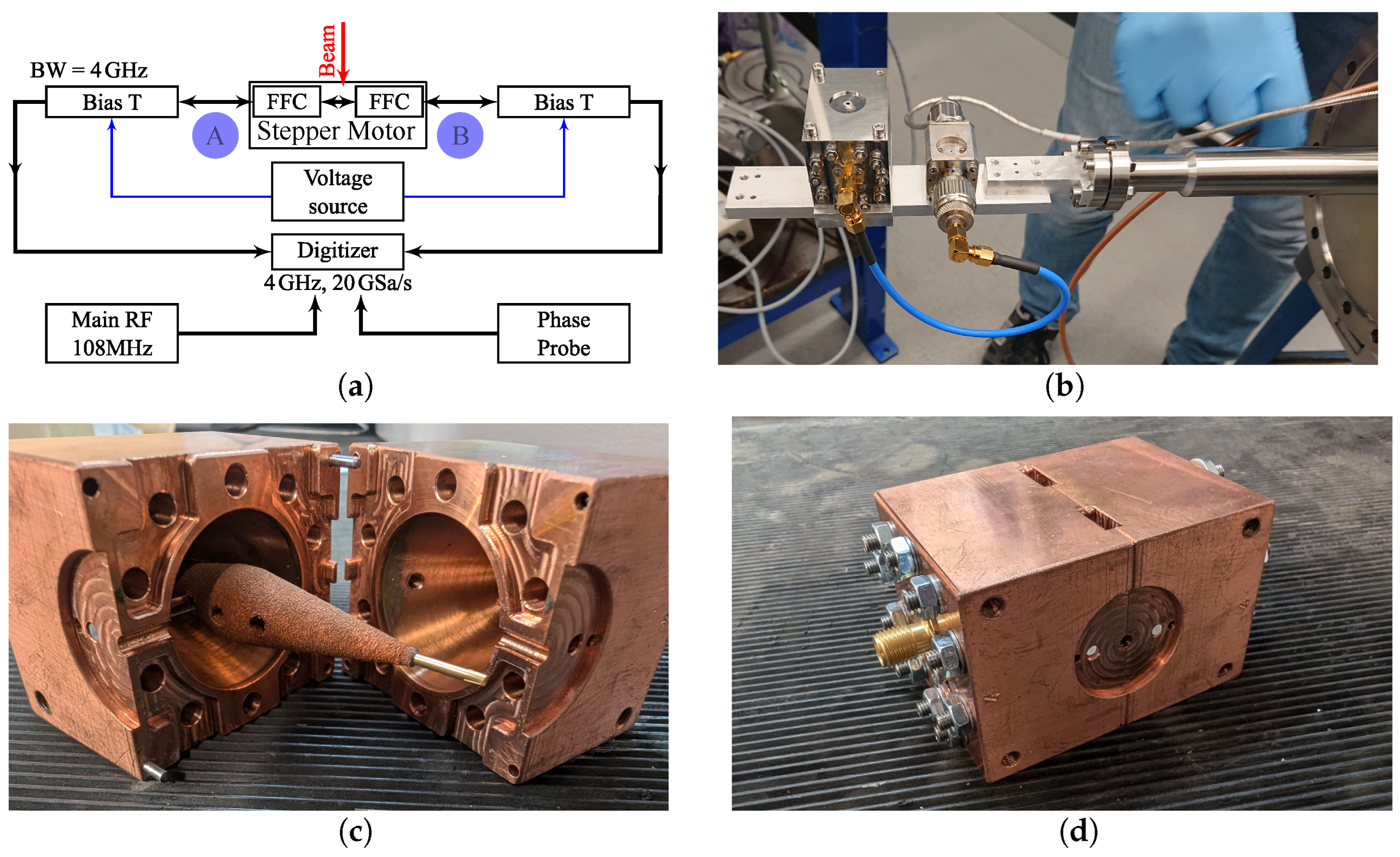

2.4. Measurements

A measurement campaign was performed to compare the two radially coupled FFCs discussed above at the X2 measurement station at GSI. The measurements were performed with an Ar

10+ beam at

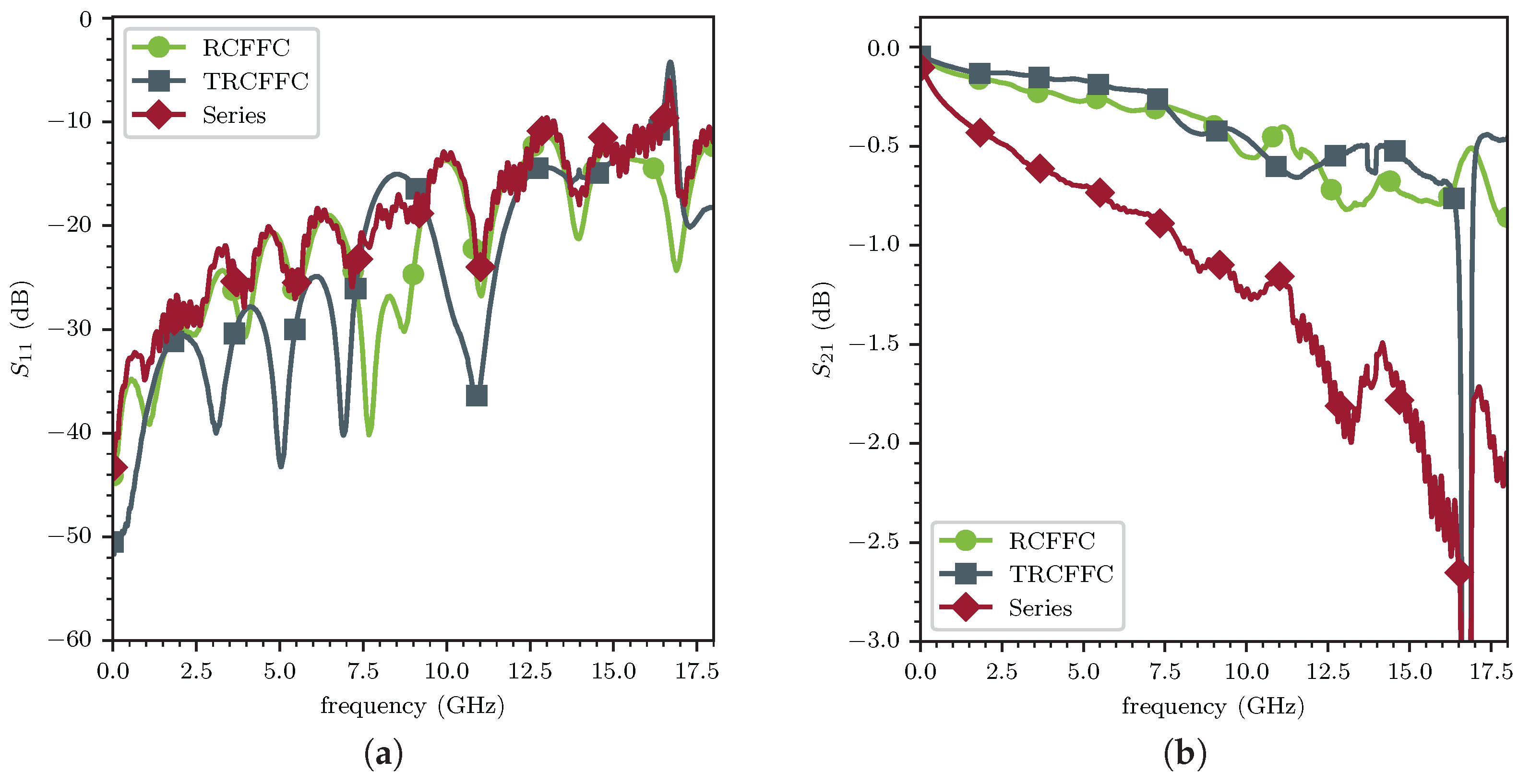

/u. Since there were only two vacuum feedthroughs available, RCFFC and TRCFFC were connected in series onto a stepper motor (see

Figure 17b). Prior to the beam measurements, the RF properties were examined in terms of reflection and transmission of each single device and connected in a series as shown in

Figure 18. The used RCFFC and TRCFFC performed similarly so that the combined reflection properties remained below

dB till 7

. The transmission was dominated by the additional 25 cm long SUCOFLEX 126E cable between them down to

dB till 7

. Using a shorter cable would further improve the transmission. So in each case, the other FFC behaved like a coaxial cable and did not affect the measurements.

The position of the FFCs was alterable in the horizontal plane by the stepper motor. The beam irradiated only one of the two FFCs at a given time. A measurement scheme with all the components is given in

Figure 17a. The bias voltage was applied through Mini-Circuits ZX85-12G-S+ bias Tees [

38] from both ports, ensuring that no DC current through the FFCs was induced. The signal was amplified with a broadband (low-noise) amplifier Mini-Circuits ZX60-14LN-S+ [

39] and measured with a four-channel Lecroy WaveRunner 9404 [

40] oscilloscope with 4

bandwidth and 20 GSa/s. In addition, the master RF signal of the UNILAC cavities was recorded to evaluate the bunch movements with respect to RF. The signal from the phase probe (PP) installed ≈0.9 m in front of the FFCs was also available for time of arrival triggering. An open, all-copper version of the TRCFFC can be seen in

Figure 17c. The collector is arranged with a glass pin inside the chassis. The sealing RF surfaces are shown.

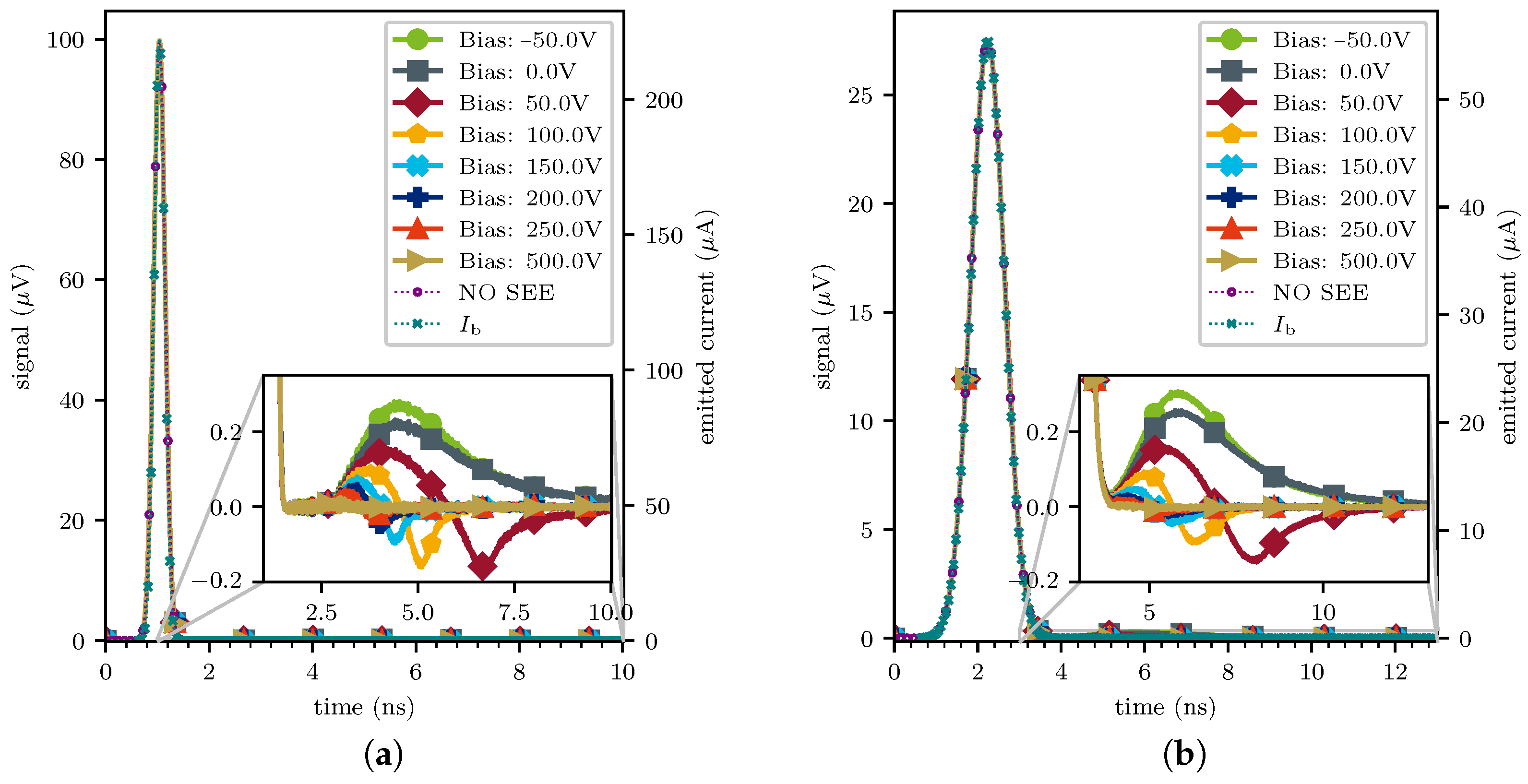

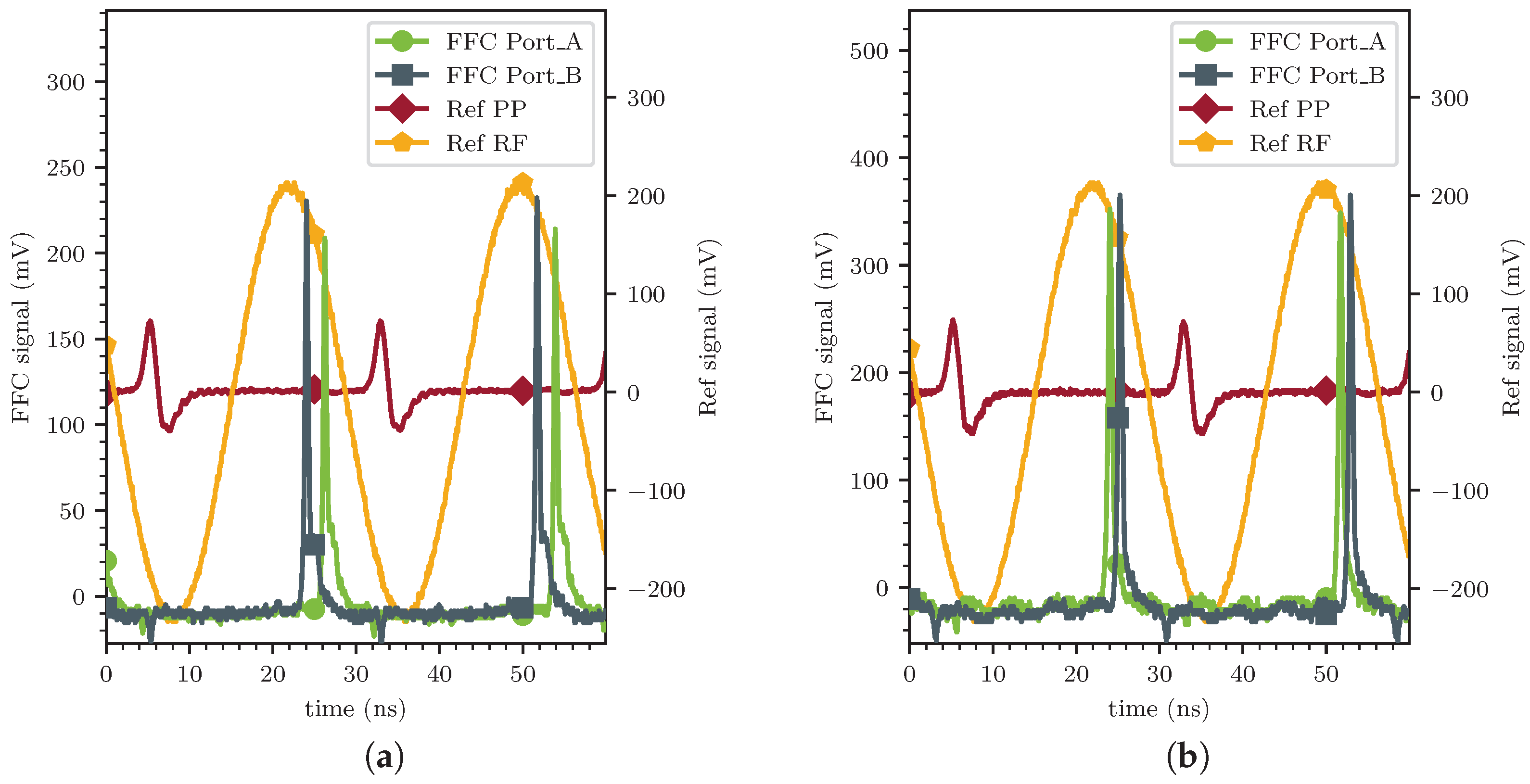

In

Figure 19a,b, examples of two consecutive bunches within a macropulse measured with the RCFFC (left) and the TRCFFC (right) at the same position with respect to the beam axis without biasing are shown. The phase probe signal and reference RF are also marked. The time difference between the FFCs A and B ports is a result of different signal path lengths. The difference in the amplitude of the signals arises mainly due to the different damping from the additional cable between the FFCs and a small additional reflection of the second FFC. In line with the expectations, the amplitude of the ion peak of the TRCFFC is higher by a factor of 1.6 compared to the RCFFC. Furthermore, the tail of the SEs is lower and shorter in the TRCFFC due to the stronger geometrical SE suppression.

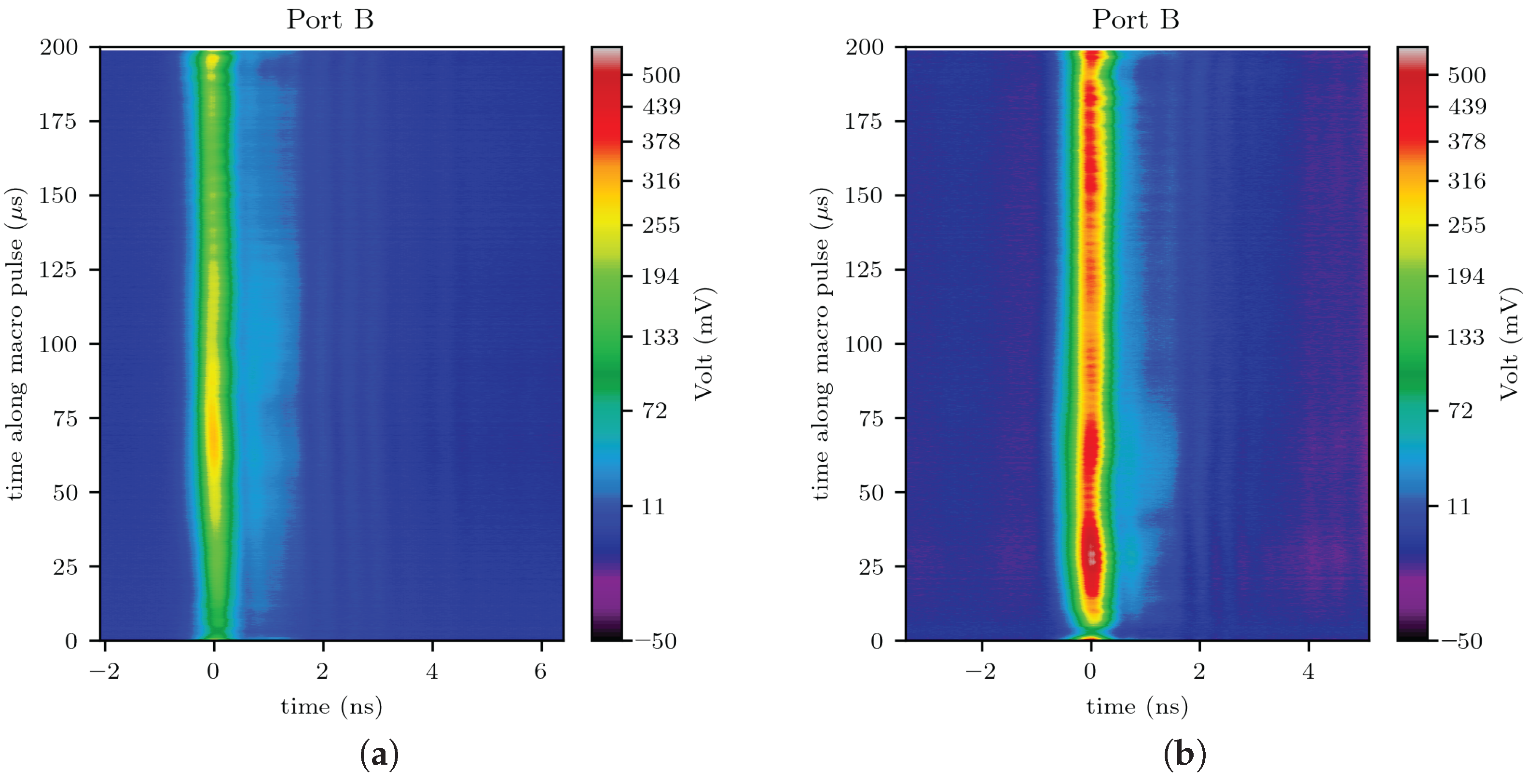

A full macropulse of about 7200 single bunches is shown in the waterfall diagram in

Figure 20, aligned by the RF signal. While the amplitude of the ion peak changes significantly along the macropulse, no strong temporal jitter is observable. No bias voltage was applied to further suppress the SEs. Hence, a light blue tail is visible after the ion peak. This tail is 2 ns long for the RCFFC and 1 ns for the TRCFFC. The amplitude of the SE tail is slightly lower for the TRCFFC and, relative to the signal strength of the ion signal, lower by a factor of 2.

Due to the pinhole in the heat shield, the FFC selects only a 1.8 mm section in the case of the TRCFFC for typical beams with a transversal extension of about 10 mm in diameter. The most obvious effect is the change in the measured amplitude depending on whether the core of the beam or the outer regions are observed. The actual shape may alter with respect to the transverse–longitudinal position of the FFC due to position-dependent effects like dispersion. In

Figure 21b, there is a second peak at

at an insertion depth of

, which was not observed at an insertion depth of

as shown in

Figure 19 and

Figure 20. A transversal sweep was performed with both FFCs through the beam. A plot of the average bunch shape of the full macropulse against the insertion depth position is shown in

Figure 21. A bias of 25 V was applied during both measurements. With both FFCs, a preceding peak for insertion depths of 20.9 cm to 21.6 cm and 16.2 cm to 16.8 cm is observed. The X2 measurement station is connected to the exit of the UNILAC accelerating structure via a series of strong dipoles providing more than a 90 degree bend. Therefore, a large dispersion is expected to be present at the FFC location, although no beamline optics simulations are available. This large dispersion allows the radially coupled FFCs to sample the energy axis via its horizontal motion, and therefore, dispersion-assisted longitudinal emittance can be estimated as discussed in [

41].

A horizontal sweep of the FFC was carried out in small steps to measure the bunch lengths. The resolution of this measurement depends on the hole size in the heat shield. Therefore, the finer pinhole of the RCFFC results in a finer measurement compared to the TRCFFC. In this measurement, the measured

between both types of FFCs can also be evaluated. The maximum intensity of the average bunch shape observed with the RCFFC is

, while the TRCFFC signal maximum is

. The measured

between both FFCs is 2.13, which roughly matches a beam width

of

according to Equation (

6). In

Figure 21b, we see a reflection at

. This reflection is also visible in

Figure 22a at 9 ns. A single mismatch likely occurred at a position approximately

from the TRCFFC and

from the RCFFC. Through the series configuration of the devices, this reflection appears in both measurements. Backtracking these distances to a common origin indicates the vacuum feedthrough of the beamline or the nearby attached bias tee outside the beamline as the most probable source of the reflection.

Finally, a bias voltage study was performed for both FFCs. The biasing scheme was applied at an insertion depth of

for the TRCFFC, while it was applied at an insertion depth of

for the RCFFC, where the second peak was not visible in the scan as shown in

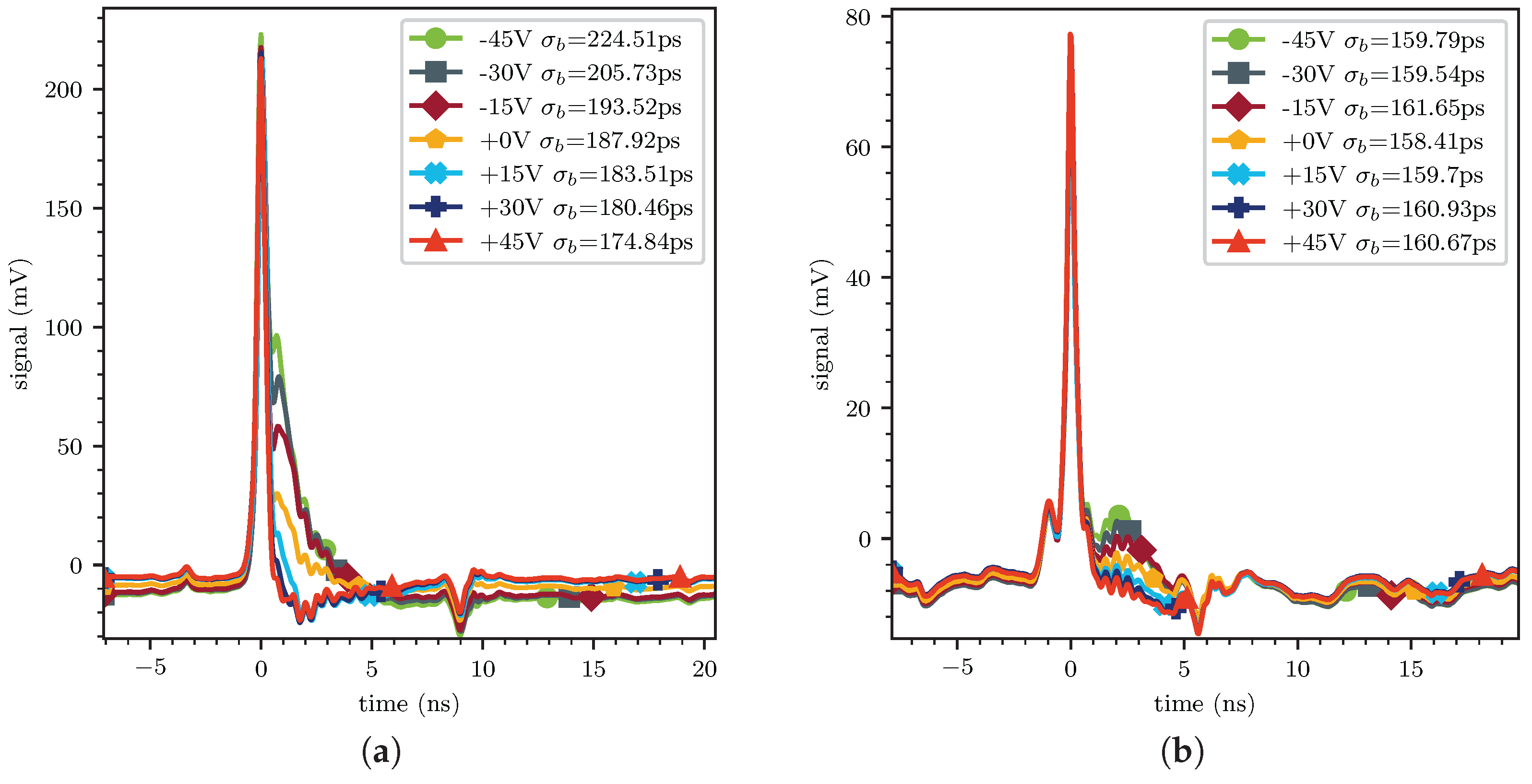

Figure 21a. To emphasize the difference in the geometrical SE suppression of both designs, the bunch shape along the macropulse in

Figure 22 was averaged for different bias voltages ranging from −45 V to 45 V. The bunch width

was estimated using the FWHM divided by 2.3548. If the bias voltage is sufficiently high, the bunch length estimation stabilizes at a certain value, even if the bias voltage is increased further. The estimated bunch length changed from 224.5

to 174.8

depending on the used bias for the RCFFC. The temporal separation and the geometrical suppression were not strong enough to suppress the SEs without a bias. A higher bias would be necessary for an accurate estimation. In contrast, the bunch width estimated with the TRCFFC ranged from 159.8

to 160.9

at the insertion position of

. Even a high negative bias had no severe impact on the estimated

. Hence, the bunch length estimation can be considered to be accurate with an average bunch length over all bias measurements of

.