A Broad Photon Energy Range Multi-Strip Imaging Array Based upon Single Crystal Diamond Schottky Photodiode

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

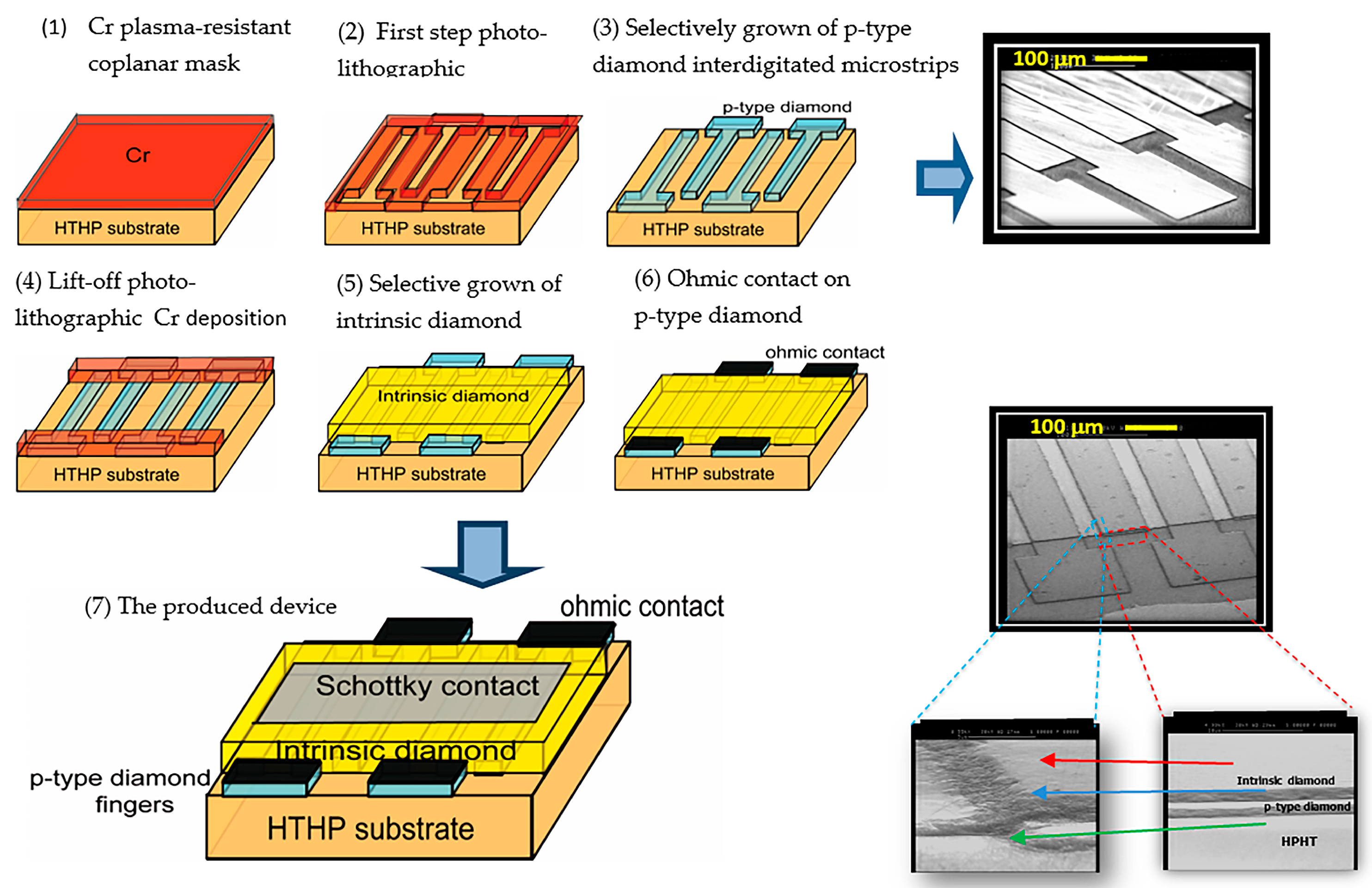

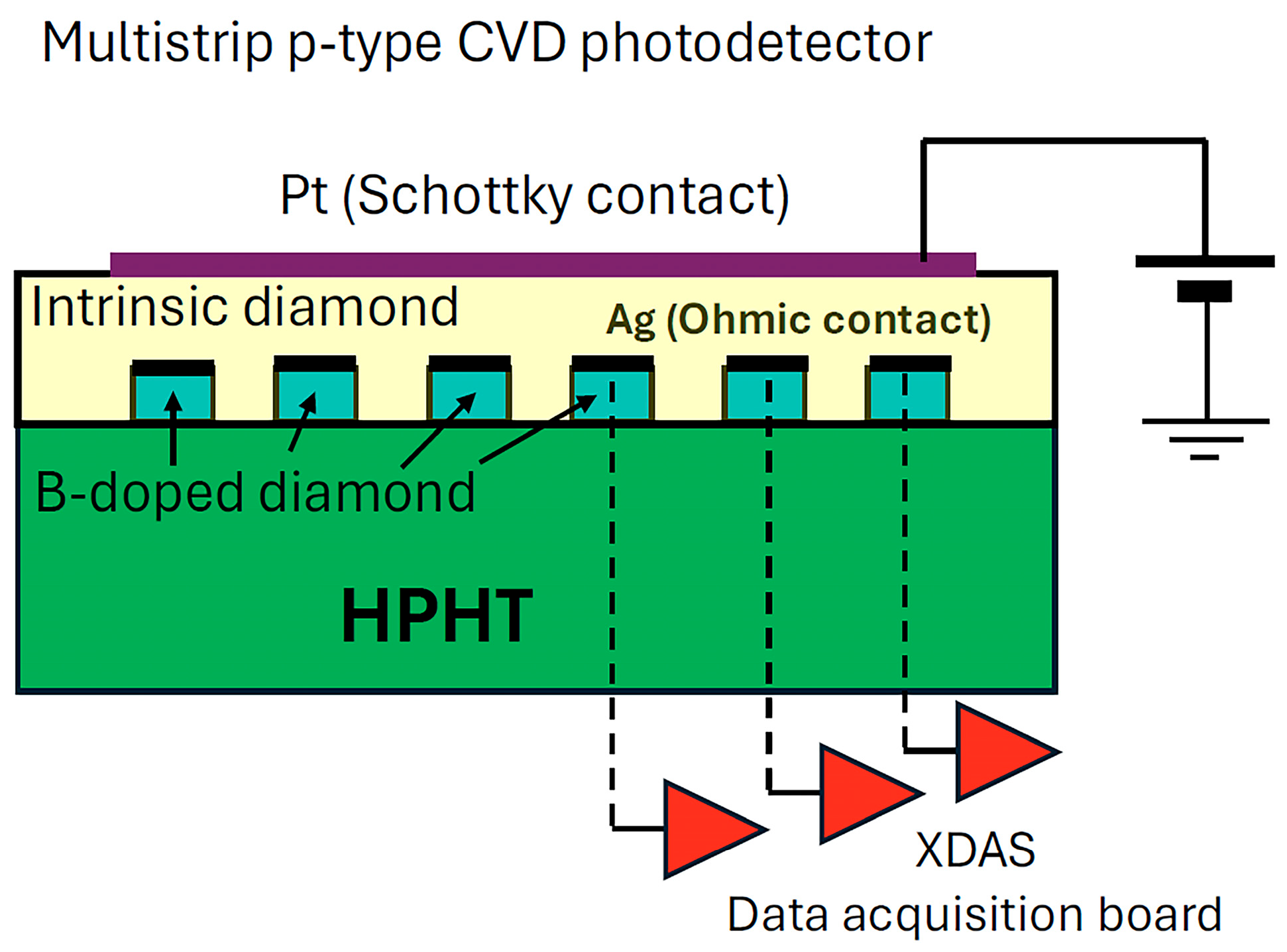

2.1. Fabrication Method

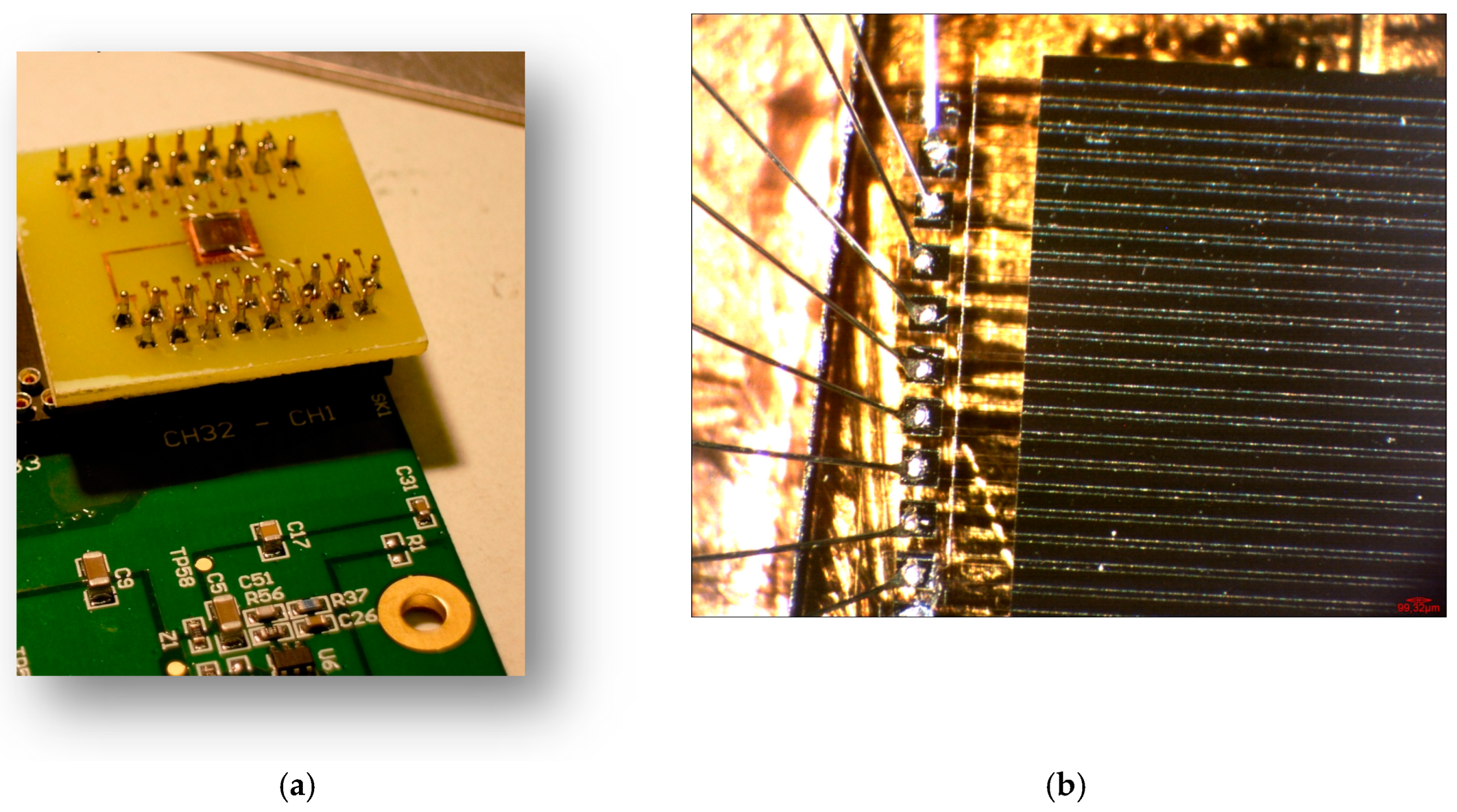

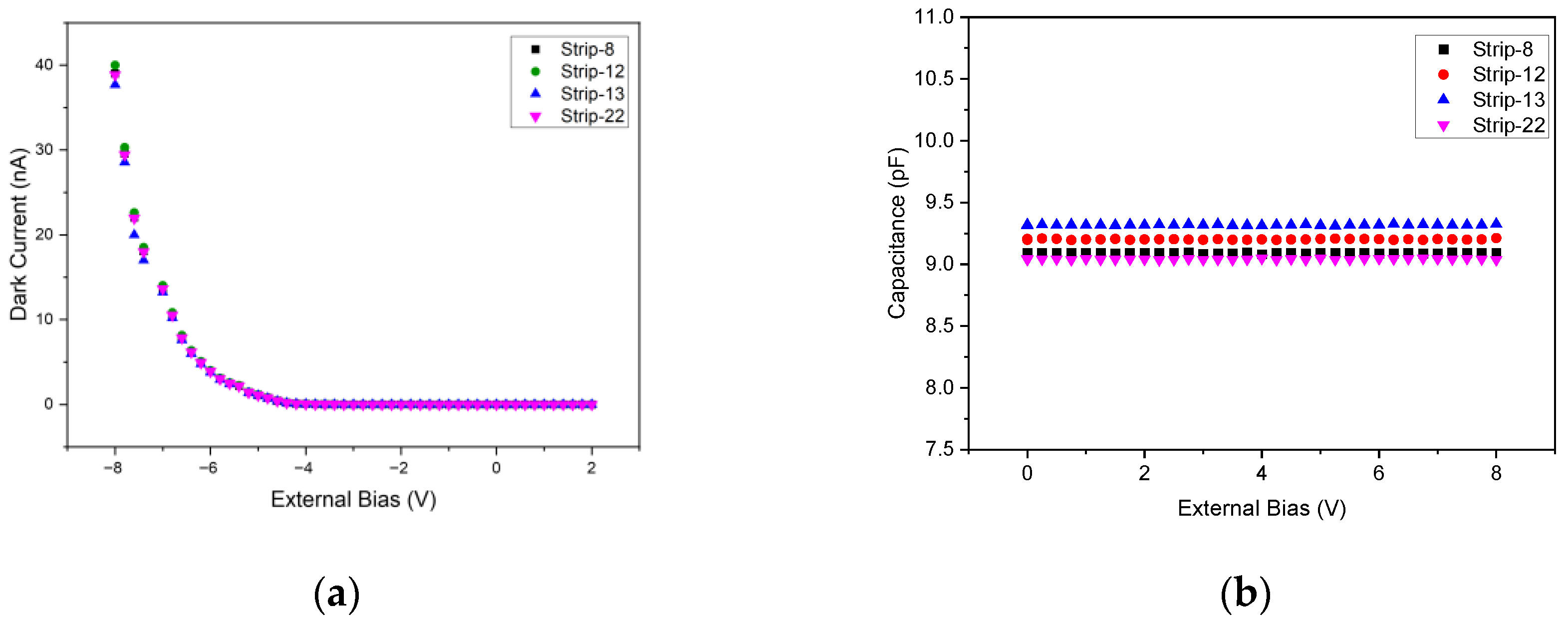

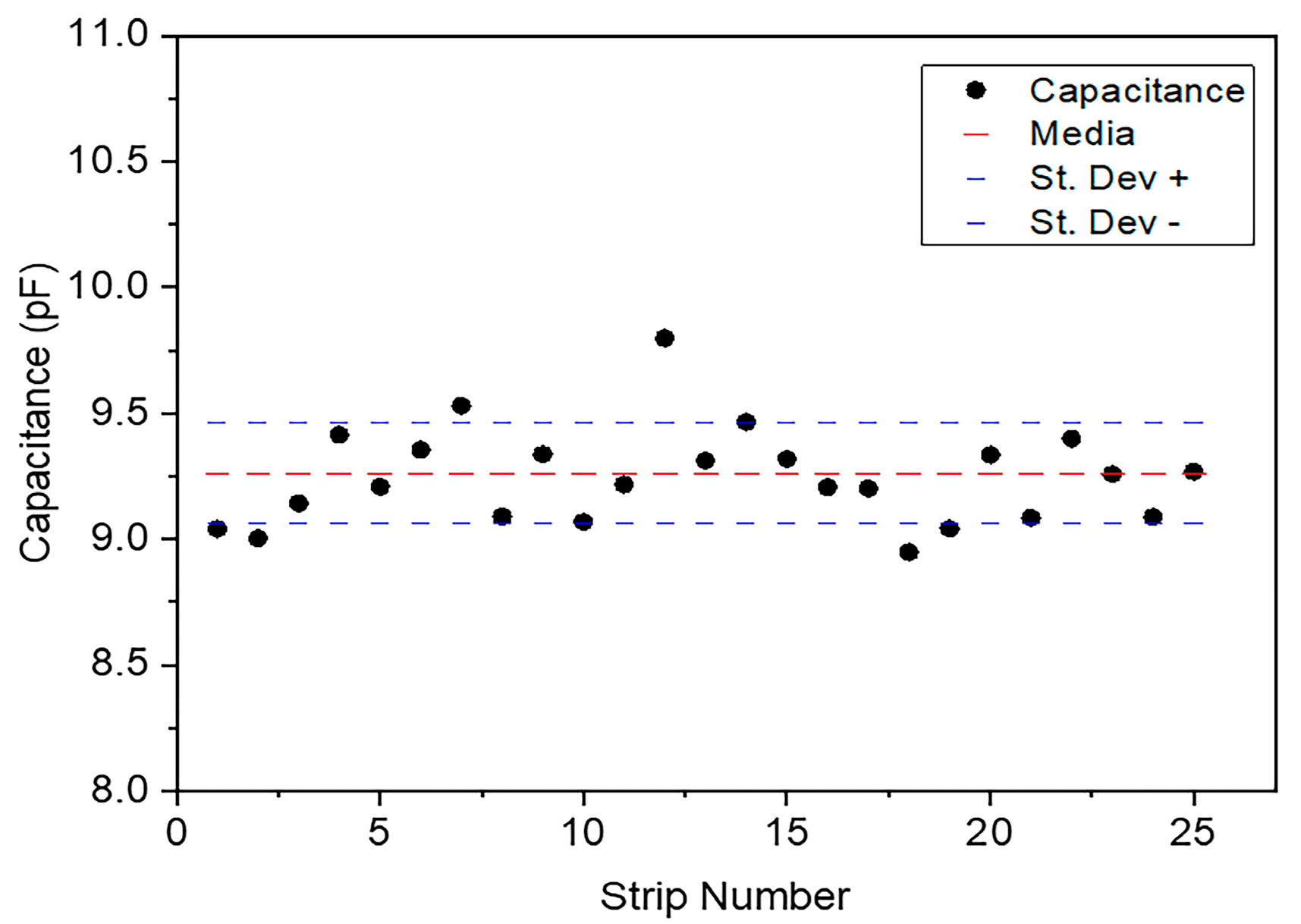

2.2. Electrical Characterization

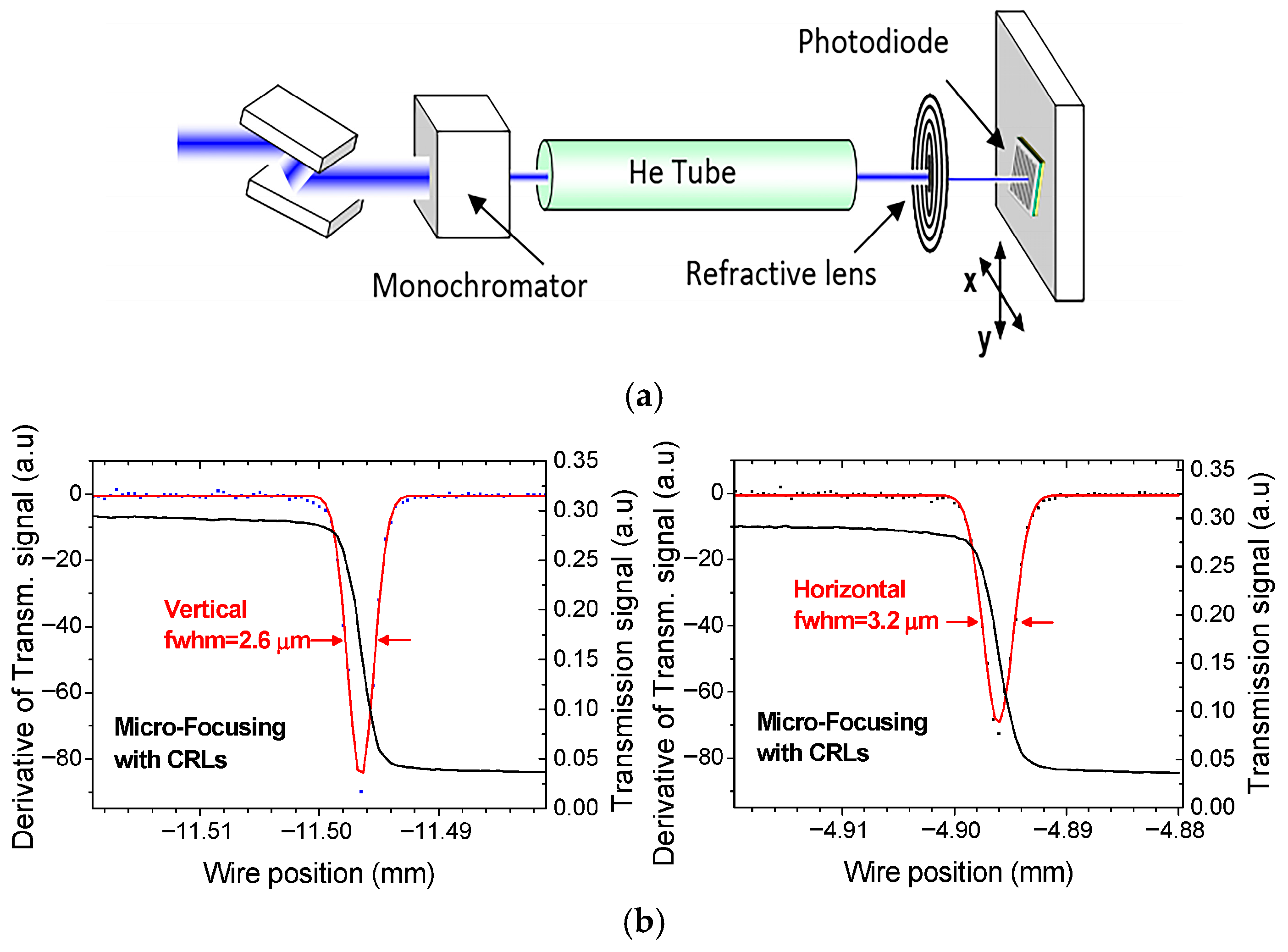

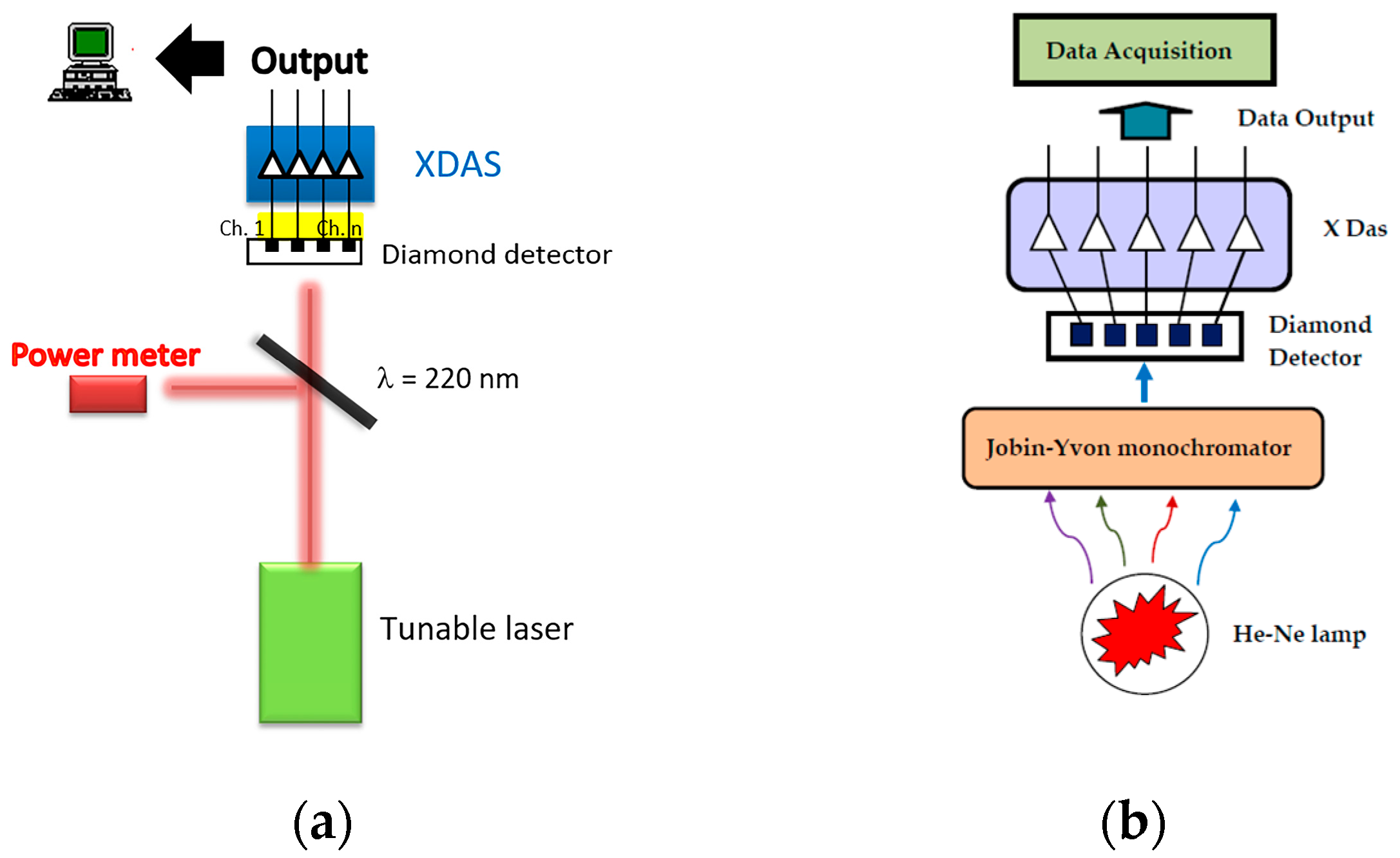

2.3. Experimental Set-Up

3. Results

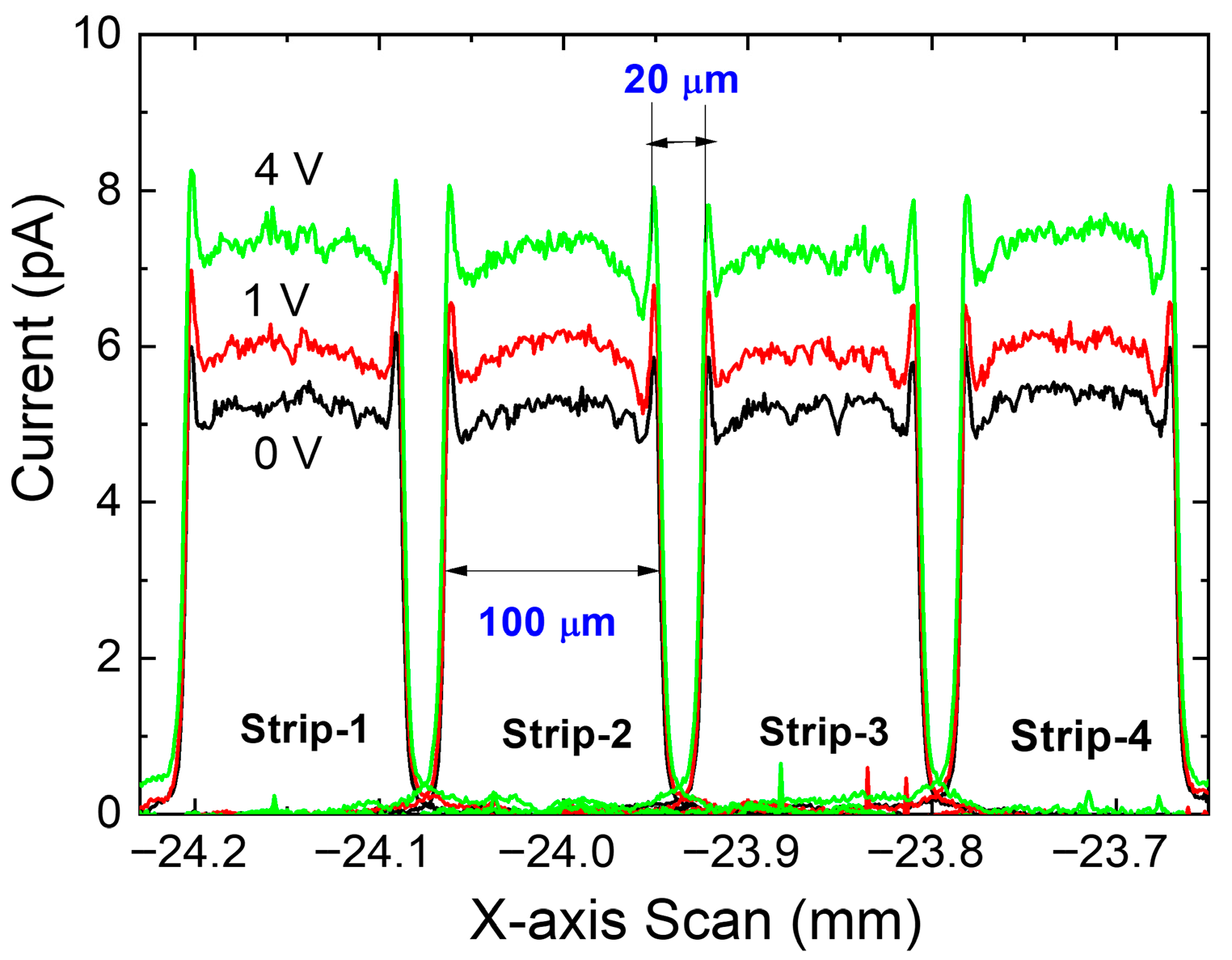

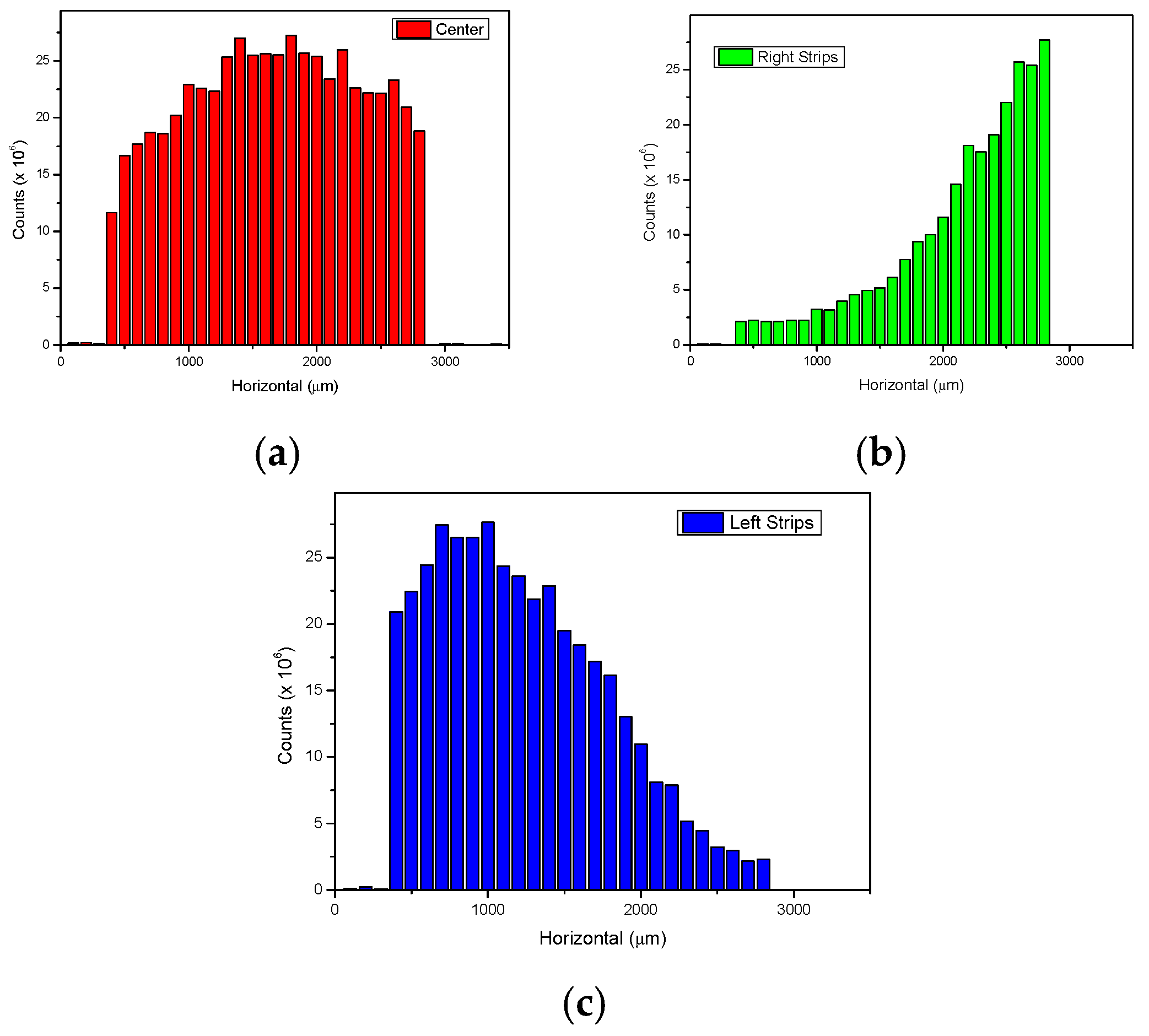

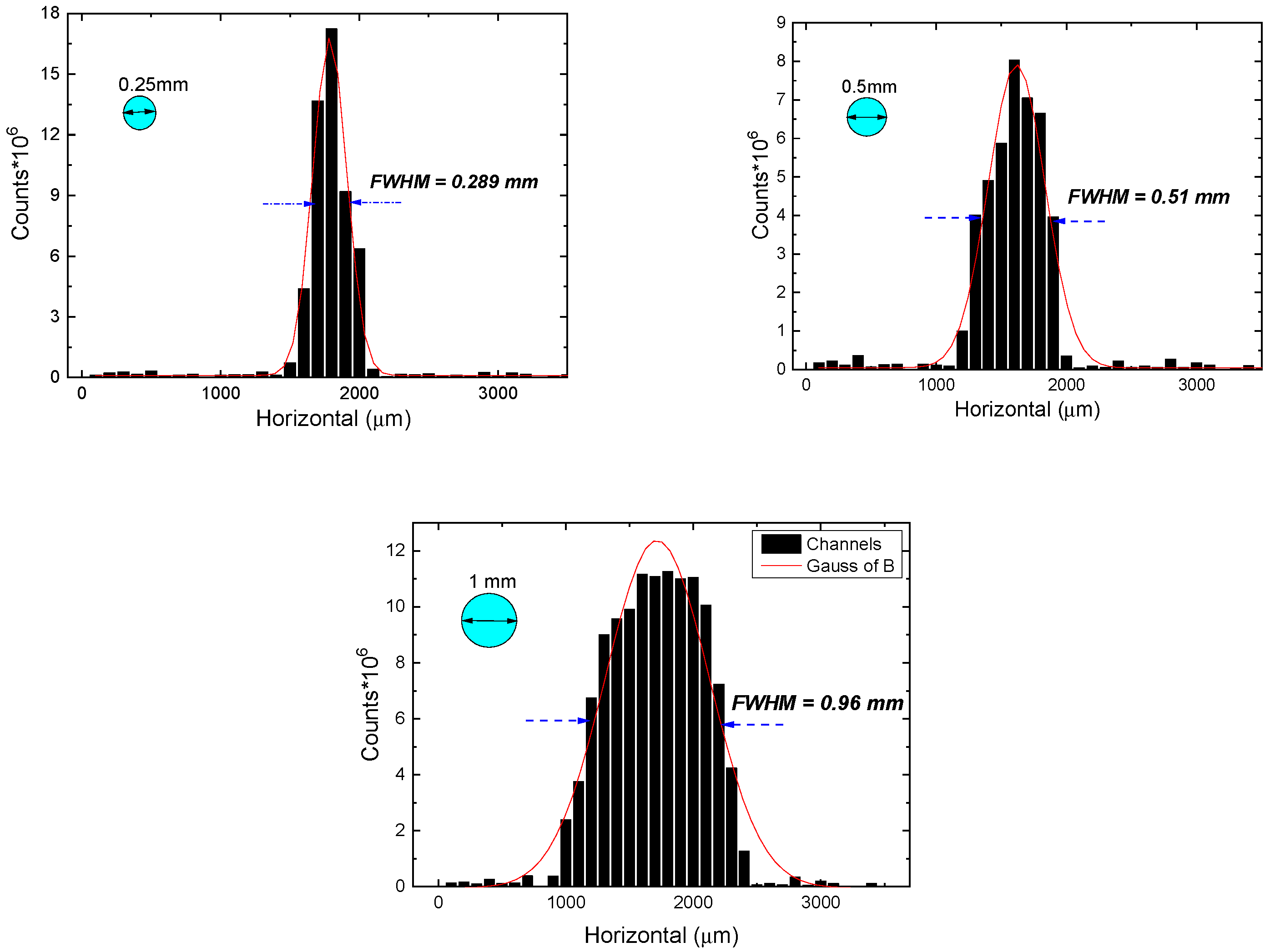

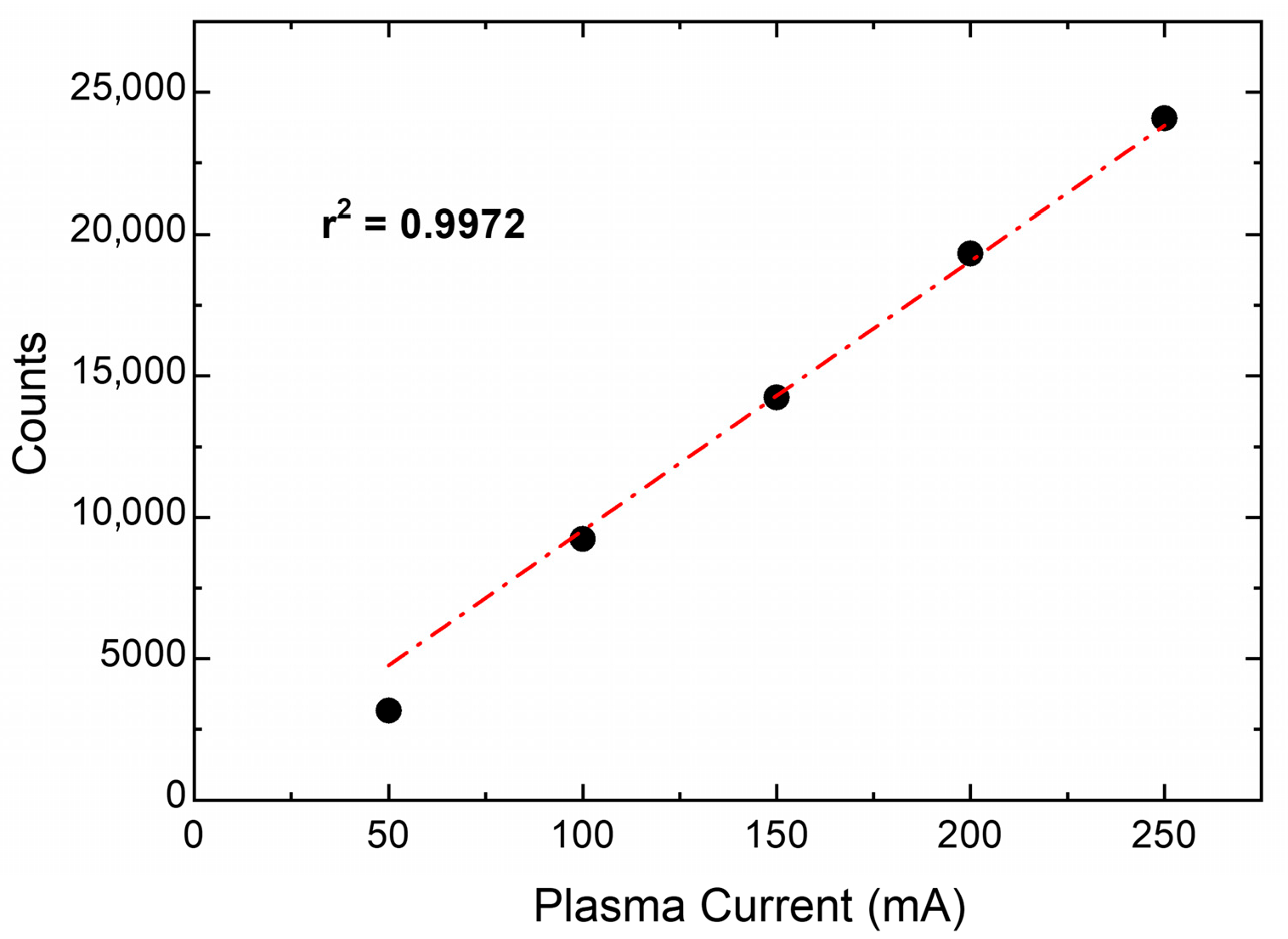

3.1. Test of the Device with SXR

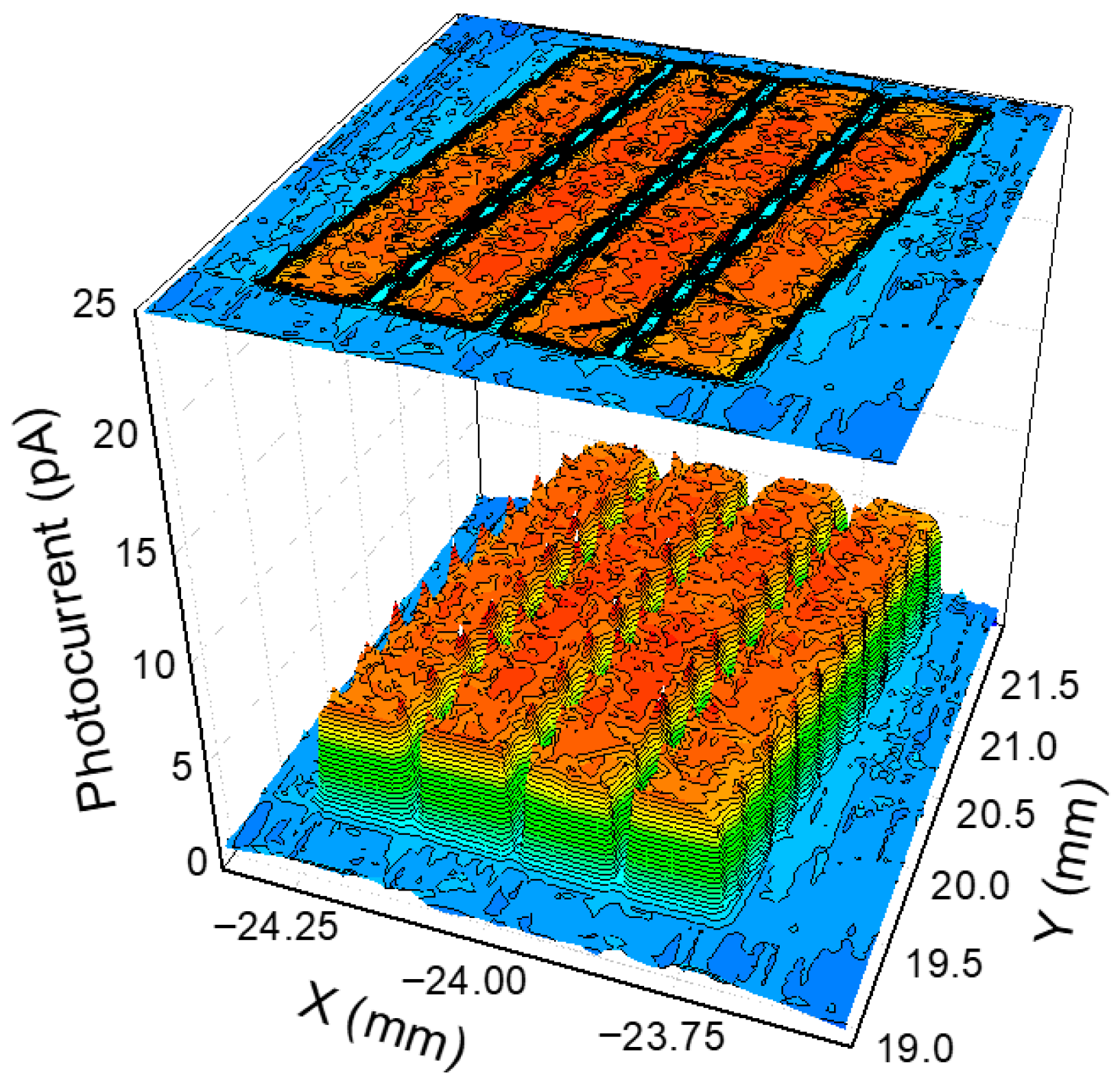

3.2. Testing of the Device with UV

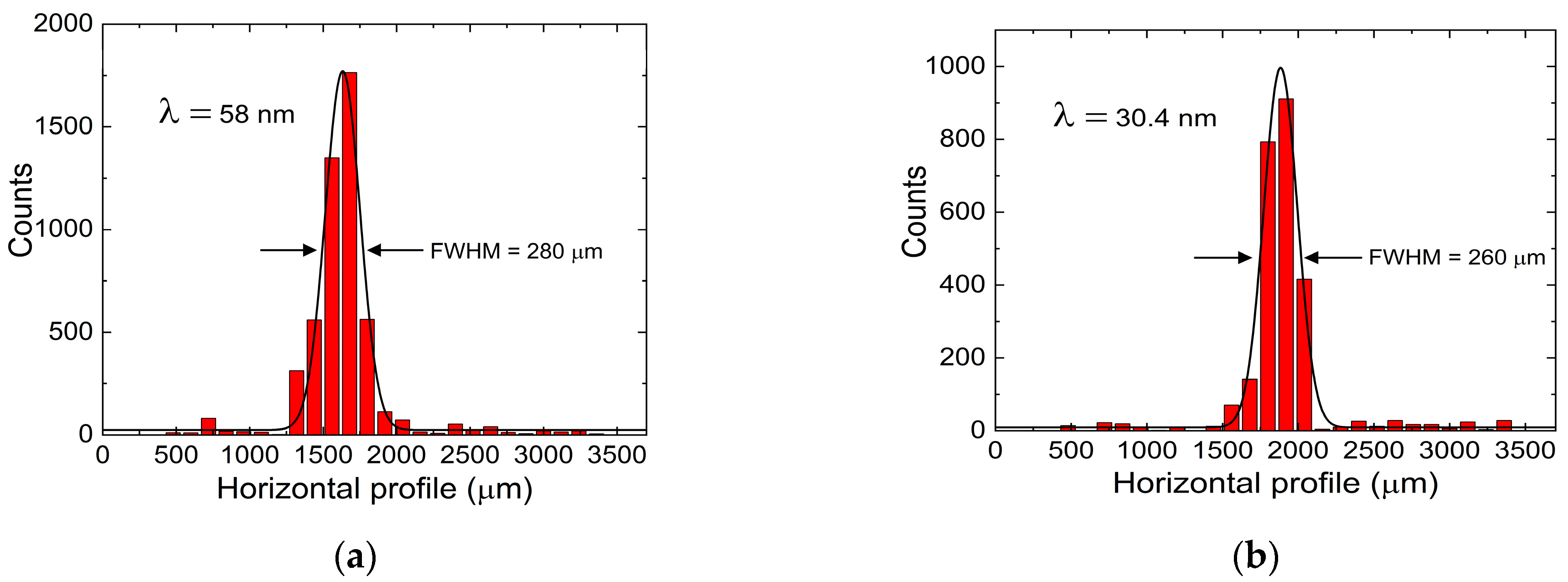

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sang, L.; Liao, M.; Sumiya, M. A Comprehensive Review of Semiconductor Ultraviolet Photodetectors: From Thin Film to One-Dimensional Nanostructures. Sensors 2013, 13, 10482–10518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelone, M.; Bombarda, F.; Cesaroni, S.; Marinelli, M.; Raso, A.M.; Verona, C.; Verona-Rinati, G. X-ray and UV detection using synthetic crystal diamond. Instruments 2025, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koizumi, S.; Nebel, C.E.; Nesladek, M. (Eds.) Physics and Application of CVD Diamond; Wiley-VCH GmbH Co. KGaA: Wetnhetm, Germany, 2008; ISBN 978-3-527-40801-6. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, L.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, N.; Lin, Z.; Cai, W.; Cheng, L.; Lu, X.; Zheng, W. Ultrafast Diamond Photodiodes for vacuum Ultraviolet Imaging in Space-Based Applications. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2025, 13, 2402601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomer, C.; Newton, M.E.; Rehmb, G.; Salter, P.S. A single-crystal diamond X-ray pixel detector with embedded graphitic electrodes. J. Synchrotron Rad. 2020, 27, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yıldız, T.C.; Freund, W.; Liu, J.; Schreck, M.; Khakhulin, D.; Yousef, H.; Milnea, C.; Grunert, J. Diamond sensors for hard X-ray energy and position resolving measurements at the European XFEL. J. Synchrotron Rad. 2024, 31, 1029–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, T.; Ding, W.; Gaowei, M.; De Geronimo, G.; Bohon, J.; Smedley, J.; Muller, E. Pixelated transmission-mode diamond X-ray detector. J. Synchrotron Rad. 2015, 22, 1396–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claps, G.; Murtas, F.; Foggetta, L.; Di Giulio, C.; Alozy, J.; Cavoto, G. Diamondpix: A CVD diamond detector with timePix3 chip interface. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2018, 65, 2743–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griesmayer, E.; Kavrigin, P.; Weiss, C. The Use of Single Crystal CVD Diamond as Position Sensitive X-ray Detector. In Proceedings of the 5th International Beam Instrumentation Conference IBIC-2016, Barcelona, Spain, 11–15 September 2016; ISBN 978-3-95450-177-9. [Google Scholar]

- Girolami, M.; Serpente, V.; Mastellone, M.; Tardocchi, M.; Rebai, M.; Xiu, Q.; Liu, J.; Sun, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Valentini, V.; et al. Self-powered solar-blind ultrafast UV-C diamond detectors with asymmetric Schottky contacts. Carbon 2022, 189, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatori, S.; Girolami, M.; Oliva, P.; Conte, G.; Bolshakov, A.; Ralchenko, V.; Konov, V. Diamond device architectures for UV laser monitoring. Laser Phys. 2016, 26, 084005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girolami, M.; Conte, G.; Salvatori, S.; Allegrini, P.; Bellucci, A.; Trucchi, D.M.; Ralchenko, V.G. Optimization of X-ray beam profilers based on CVD diamond detectors. J. Instrum. 2012, 7, C11005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desjardins, K.; Bordessoule, M.; Pomorski, M. X-ray position-sensitive duo-lateral diamond detectors at SOLEIL. J. Synchrotron Rad. 2018, 25, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, T.; Hayashi, K. Spectral responsivity measurements of photoconductive diamond detectors in the vacuum ultraviolet region distinguishing between internal photocurrent and photoemission current. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2005, 86, 122113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciancaglioni, I.; Marinelli, M.; Milani, E.; Prestopino, G.; Verona, C.; Verona-Rinati, G.; Angelone, M.; Pillon, M. Secondary electron emission in extreme-UV detectors: Application to diamond based devices. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 110, 014501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaviva, S.; Marinelli, M.; Milani, E.; Prestopino, G.; Tucciarone, A.; Verona, C.; Verona-Rinati, G.; Angelone, M.; Pillon, M. Extreme UV photodetectors based on CVD single crystal diamond in a p-type/intrinsic/metal configuration. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2009, 18, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelone, M.; Pillon, M.; Marinelli, M.; Milani, E.; Prestopino, G.; Verona, C.; Verona-Rinati, G.; Coffey, I.; Murari, A.; Tartoni, N.; et al. Single crystal artificial diamond detectors for VUV and soft X-rays measurements on JET thermonuclear fusion plasma. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. 2010, A623, 726–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prins, J.F. Preparation of ohmic contacts to semiconducting diamond. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 1989, 22, 1562–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.Y.; Zaouk, R.; Madou, M.J. Fabrication of Microelectrodes Using the Lift-Off Technique. In Microfluidic Techniques; Methods in Molecular Biology™; Minteer, S.D., Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2006; Volume 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciancaglioni, I.; Di Venanzio, C.; Marinelli, M.; Milani, E.; Prestopino, G.; Verona, C.; Verona-Rinati, G.; Angelone, M.; Pillon, M.; Tartoni, N. Influence of the metallic contact in extreme-ultraviolet and soft x-ray diamond based Schottky photodiodes. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 110, 054513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.diamond.ac.uk/Science/Research/Optics/B16.html (accessed on 19 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Verona, C.; Angelone, M.; Marinelli, M.; Verona-Rinati, G. A Broad Photon Energy Range Multi-Strip Imaging Array Based upon Single Crystal Diamond Schottky Photodiode. Instruments 2025, 9, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/instruments9040026

Verona C, Angelone M, Marinelli M, Verona-Rinati G. A Broad Photon Energy Range Multi-Strip Imaging Array Based upon Single Crystal Diamond Schottky Photodiode. Instruments. 2025; 9(4):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/instruments9040026

Chicago/Turabian StyleVerona, Claudio, Maurizio Angelone, Marco Marinelli, and Gianluca Verona-Rinati. 2025. "A Broad Photon Energy Range Multi-Strip Imaging Array Based upon Single Crystal Diamond Schottky Photodiode" Instruments 9, no. 4: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/instruments9040026

APA StyleVerona, C., Angelone, M., Marinelli, M., & Verona-Rinati, G. (2025). A Broad Photon Energy Range Multi-Strip Imaging Array Based upon Single Crystal Diamond Schottky Photodiode. Instruments, 9(4), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/instruments9040026