Critical Temperature in the BCS-BEC Crossover with Spin-Orbit Coupling

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Basic Concepts in Ultracold Atomic Physics

- Magnetic Traps

- Optical Traps

- Laser or Doppler Cooling

- Evaporative Cooling

1.2. Artificial Spin-Orbit Interaction in Ultracold Gases

2. Two-Body Scattering Problem

2.1. Two-Body Scattering Matrix

2.2. Renormalization of the Contact Potential

2.3. With Spin-Orbit Coupling

3. Fermi Gas with Attractive Potential

3.1. Gap Equation

BCS Superconductors

3.2. Number Equation

3.2.1. Mean Field

- At .

- At .

3.2.2. Inclusion of the Gaussian Fluctuations

4. BCS-BEC Crossover

4.1. Mean Field Theory

4.1.1. Weak Coupling

4.1.2. Strong Coupling

4.1.3. Along the Crossover

4.2. Beyond Mean Field: Gaussian Fluctuations

4.2.1. Weak Coupling

4.2.2. Strong Coupling

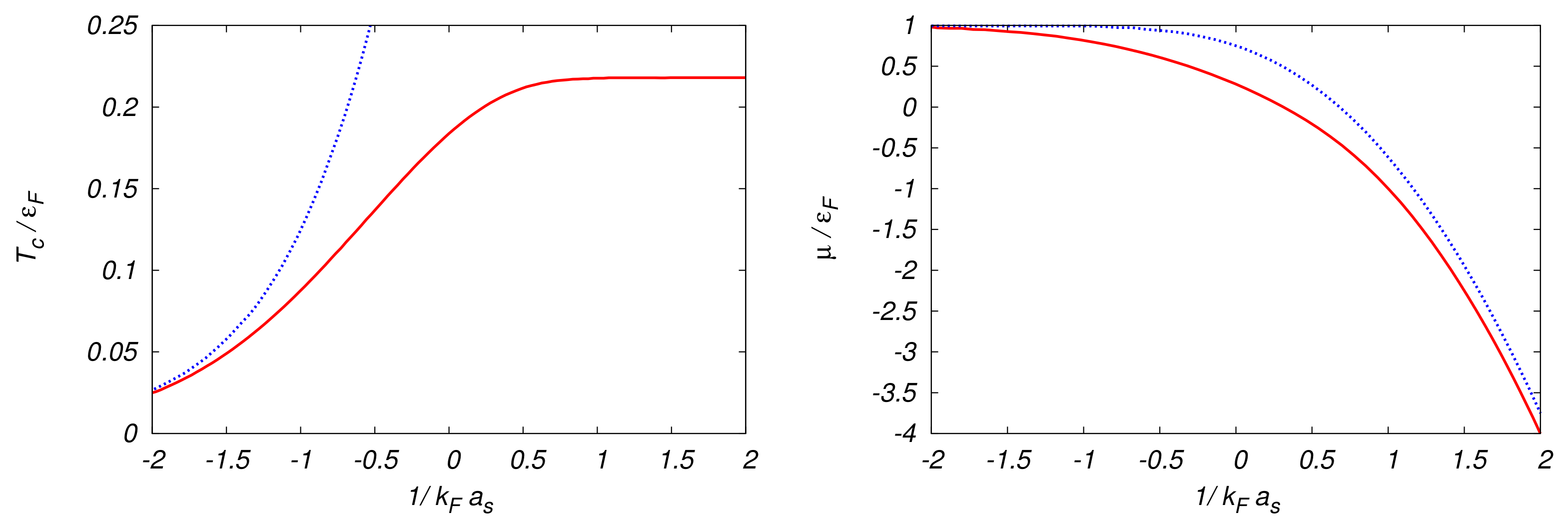

4.2.3. Full Crossover

- Bosonic Approximation

- Exact Gaussian Fluctuations

5. Fermi Gas with Spin-Orbit Interaction, Zeeman Term and Attractive Potential

5.1. Gap Equation

5.2. Number Equation

5.2.1. Mean Field

- At .

- At T=.

5.2.2. Inclusion of Gaussian Fluctuations at

5.3. Critical Point

6. BCS-BEC Crossover with Spin-Orbit Coupling

6.1. Mean Field

6.1.1. Weak Coupling

6.1.2. Strong Coupling

6.1.3. Full Crossover

6.1.4. Special Case: Equal Rashba and Dresselhaus

6.2. With Gaussian Fluctuations

6.2.1. Special Case: Equal Rashba and Dresselhaus

6.2.2. Special Case: Only Zeeman Term

6.2.3. Weak Coupling

6.2.4. Strong Coupling

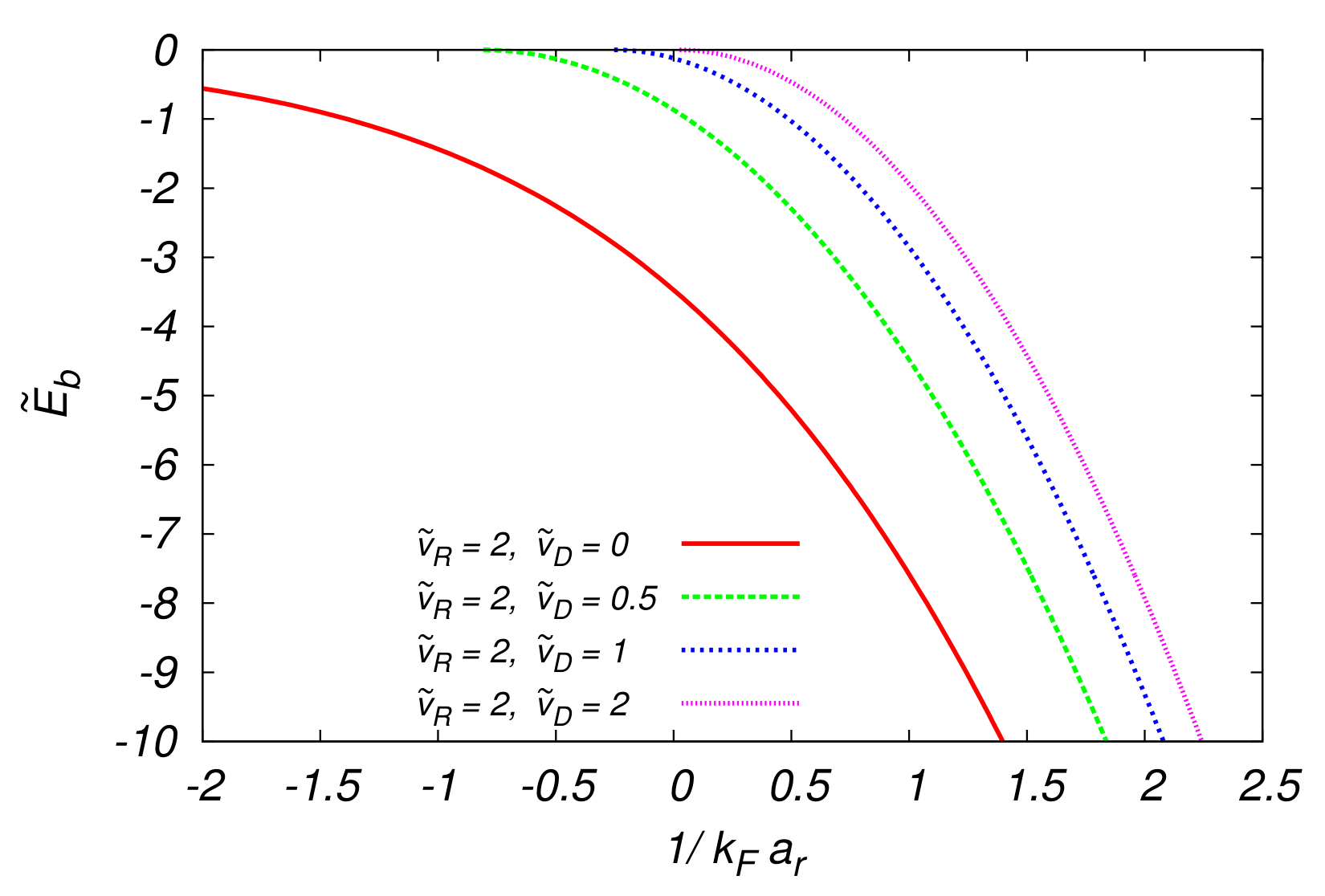

- Binding Energy

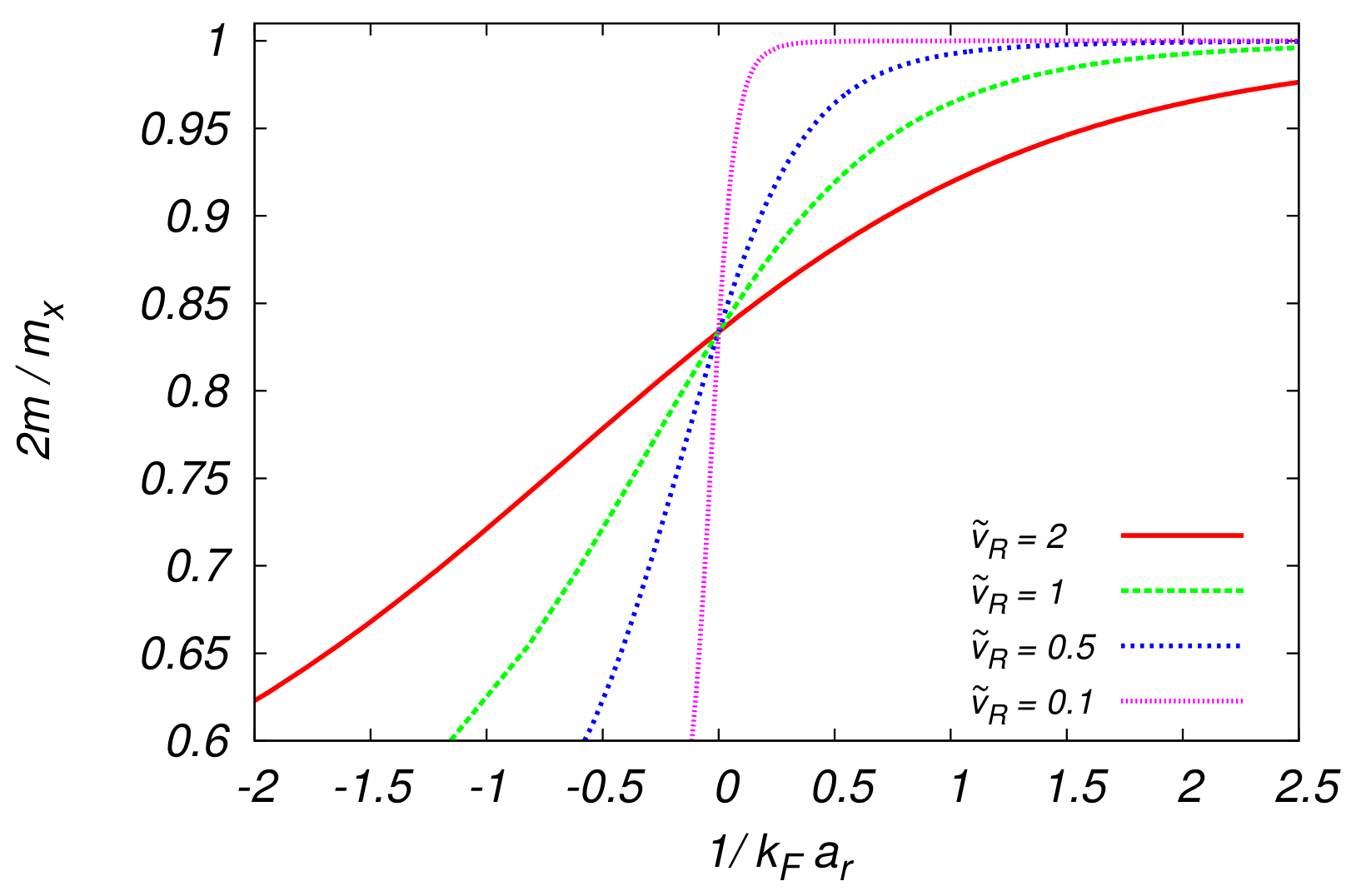

- Effective Masses

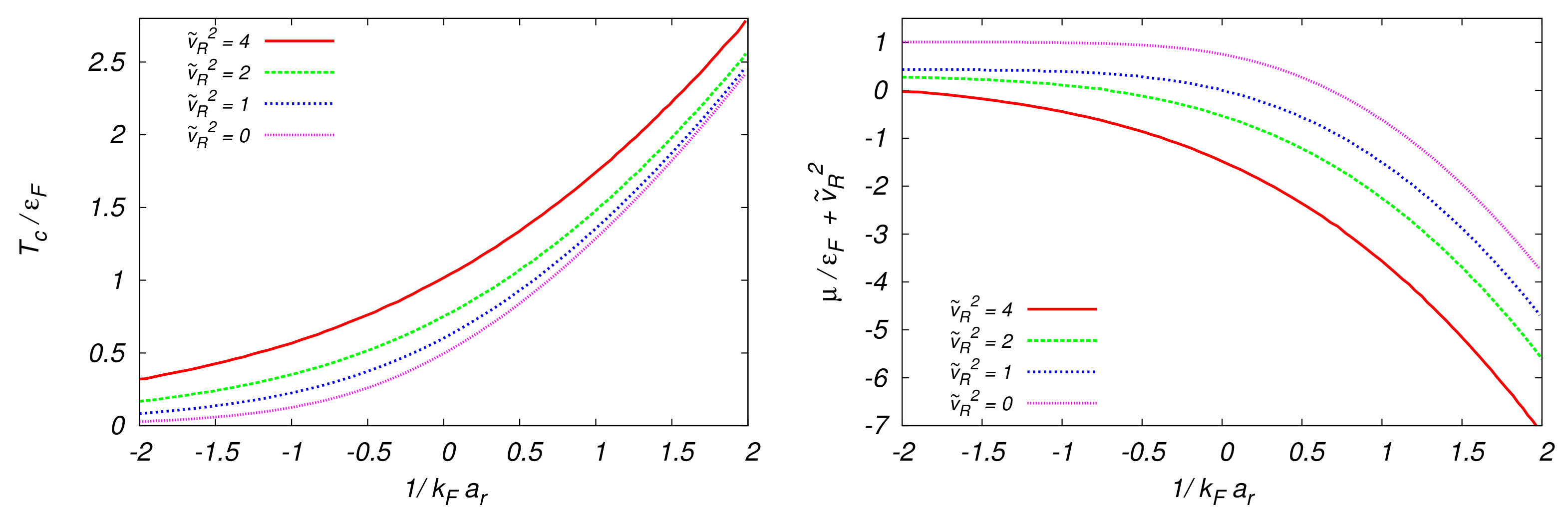

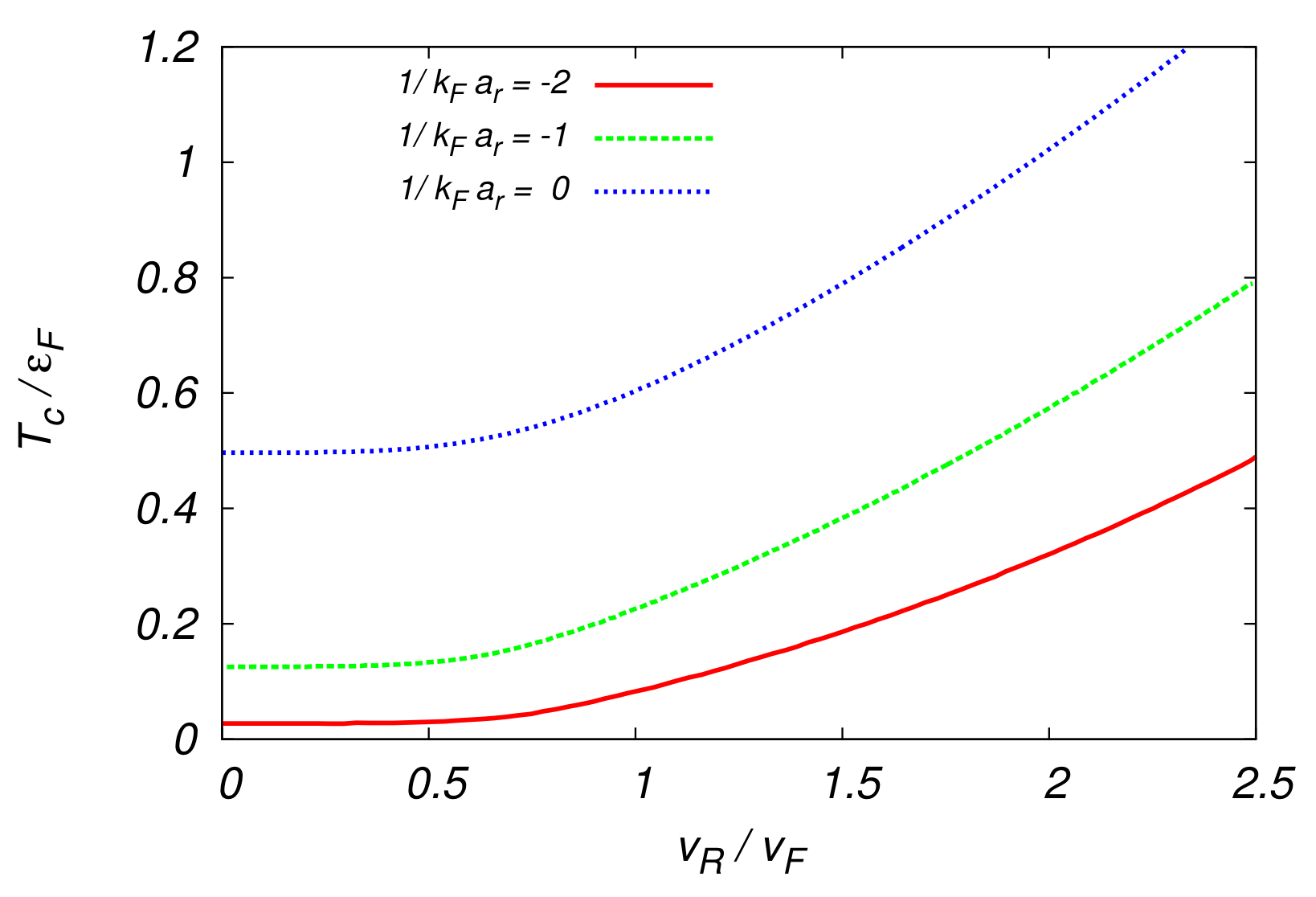

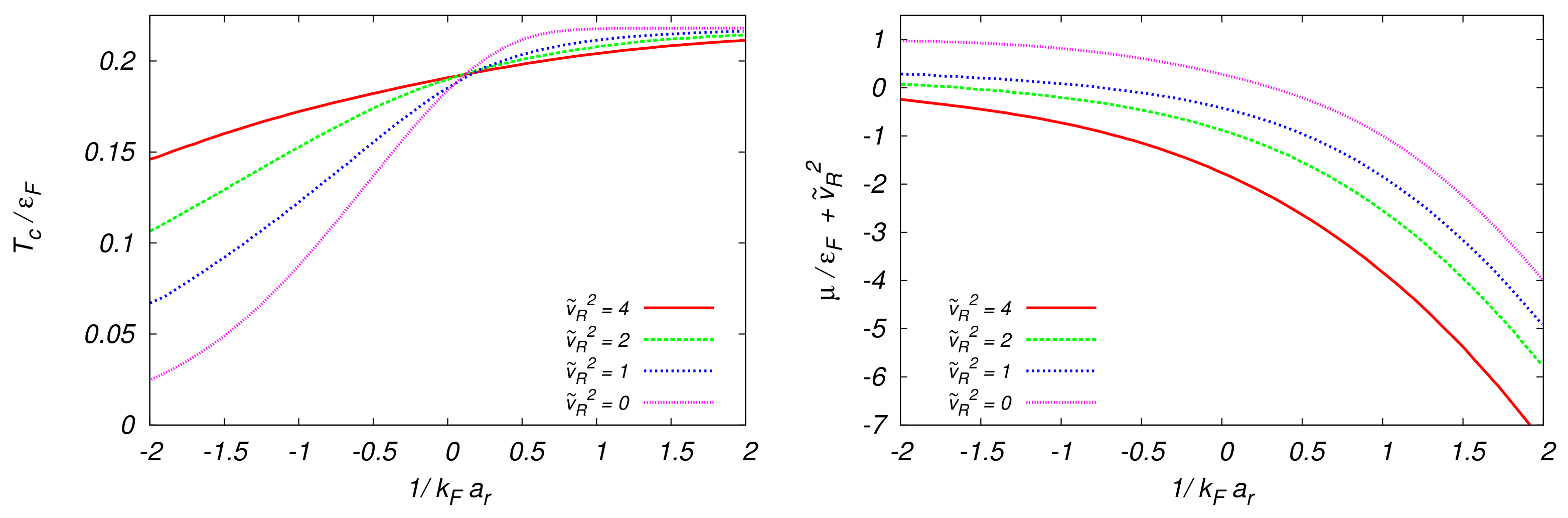

6.2.5. Full Crossover

- Bosonic Approximation

- Further Improvements

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Scattering Amplitude

Appendix B. Partial Wave Expansion

Appendix C. Asymptotic Solutions of the Schrödinger Equation

- Contact Potentials

- Regularized Delta-Funcion

- Bare Delta-Function

Appendix D. Scattering Problem with Spin-Orbit Coupling

Appendix D.1. Renormalization Condition for a Contact Potential

References

- Bardeen, J.; Cooper, L.N.; Schrieffer, J.R. Theory of Superconductivity. Phys. Rev. 1957, 106, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, L.N. Theory of Superconductivity. Phys. Rev. 1956, 104, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagles, D.M. Possible Pairing without Superconductivity at Low Carrier Concentrations in Bulk and Thin-Film Superconducting Semiconductors. Phys. Rev. 1969, 186, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozires, P.; Schmitt-Rink, S. Bose condensation in an attractive fermion gas: From weak to strong coupling superconductivity. J. Low Temp. Phys. 1985, 59, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micnas, R.; Ranninger, J.; Robaszkiewicz, S. Superconductivity in Narrow-Band Systems with Local Nonretarded Attractive Interactions. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1990, 62, 113–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednorz, J.G.; Mueller, K.A. Possible high Tc superconductivity in the Ba-La-Cu-O system. Zeitschrift für Physik B 1986, 64, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo, C.A.R.S.; Randeria, M.; Engelbrecht, J.R. Crossover from BCS to Bose superconductivity: Transition temperature and time-dependent Ginzburg-Landau theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1993, 71, 3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, K.B.; Mewes, M.O.; Andrews, M.R.; van Druten, N.J.; Durfee, D.S.; Kurn, D.M.; Ketterle, W. Bose-Einstein Condensation in a Gas of Sodium Atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1995, 75, 3969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inouye, S.; Andrews, M.R.; Stenger, J.; Miesner, H.-J.; Stamper-Kurn, D.M.; Ketterle, W. Observation of Feshbach resonances in a BoseEinstein condensate. Nature 1998, 392, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courteille, P.; Freeland, R.S.; Heinzen, D.J.; Abeelen, F.A.V.; Verhaar, B.J. Observation of a Feshbach Resonance in Cold Atom Scattering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998, 81, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMarco, B.; Jin, D.S. Onset of Fermi Degeneracy in a Trapped Atomic Gas. Science 1999, 285, 1703–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftus, T.; Regal, C.A.; Ticknor, C.; Bohn, J.L.; Jin, D.S. Resonant Control of Elastic Collisions in an Optically Trapped Fermi Gas of Atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 88, 173201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regal, C.A.; Jin, D.S. Measurement of positive and negative scattering lengths in a fermi gas of atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003, 90, 230404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, C.; Grimm, R.; Julienne, P.; Tiesinga, E. Feshbach resonances in ultracold gases. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2010, 82, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regal, C.A.; Greiner, M.; Jin, D.S. Observation of Resonance Condensation of Fermionic Atom Pairs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 92, 040403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwierlein, M.W.; Stan, C.A.; Schunck, C.H.; Raupach, S.M.F.; Kerman, A.J.; Ketterle, W. Condensation of Pairs of Fermionic Atoms near a Feshbach Resonance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 92, 120403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourdel, T.; Khaykovich, L.; Cubizolles, J.; Chevy, J.Z.F.; Teichmann, M.; Tarruell, L.; Kokkelmans, S.J.J.M.F.; Salomon, C. Experimental Study of the BEC-BCS Crossover Region in Lithium 6. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 93, 050401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinast, J.; Turlapov, A.; Thomas, J.E.; Chen, Q.; Stajic, J.; Levin, K. Heat Capacity of a Strongly Interacting Fermi Gas. Science 2005, 307, 1296–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-J.; Jimnez-Garca, K.; Spielman, I.B. Spinorbit-coupled BoseEinstein condensates. Nature 2011, 471, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalibard, J.; Gerbier, F.; Juzeliunas, G.; Ohberg, P. Colloquium: Artificial gauge potentials for neutral atoms. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2011, 83, 1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Yu, Z.-Q.; Fu, Z.; Miao, J.; Huang, L.; Chai, S.; Zhai, H.; Zhang, J. Spin-Orbit Coupled Degenerate Fermi Gases. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 109, 095301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheuk, L.W.; Sommer, A.T.; Hadzibabic, Z.; Yefsah, T.; Bakr, W.S.; Zwierlein, M.W. Spin-injection spectroscopy of a spin-orbit coupled Fermi gas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 109, 095302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bychkov, Y.A.; Rashba, E.I.J. Oscillatory effects and the magnetic susceptibility of carriers in inversion layers. J. Phys. C 1984, 17, 6039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresselhaus, G. Spin-orbit coupling effects in zinc blende structures. Phys. Rev. 1955, 100, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyasanakere, J.P.; Shenoy, V.B. Bound states of two spin-12 fermions in a synthetic non-Abelian gauge field. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 83, 094515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyasanakere, J.P.; Zhang, S.; Shenoy, V.B. BCS-BEC crossover induced by a synthetic non-Abelian gauge field. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 84, 014512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, M.; Tewari, S.; Zhang, C. BCS-BEC crossover and topological phase transition in 3D spin-orbit coupled degenerate Fermi gases. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 107, 195303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, H.; Jiang, L.; Liu, X.; Pu, H. Probing anisotropic superfluidity in atomic Fermi gases with Rashba spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 107, 195304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.; Zhai, H. Spin-orbit coupled Fermi gases across a Feshbach resonance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 107, 195305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iskin, M.; Subasi, A.L. Stability of spin-orbit coupled Fermi gases with population imbalance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 107, 050402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, W.; Guo, G.-C. Phase separation in a polarized Fermi gas with spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. A 2011, 84, 031608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Anna, L.; Mazzarella, G.; Salasnich, L. Condensate fraction of a resonant Fermi gas with spin-orbit coupling in three and two dimensions. Phys. Rev. A 2011, 84, 033633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iskin, M.; Subasi, A.L. Quantum phases of atomic Fermi gases with anisotropic spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. A 2011, 84, 043621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, W.; Yi, W. Topological superfluid in a trapped two-dimensional polarized Fermi gas with spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. A 2011, 84, 063603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Liu, X.-J.; Hu, H.; Pu, H. Rashba spin-orbit-coupled atomic Fermi gases. Phys. Rev. A 2011, 84, 063618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; de Melo, C.A.R.S. Evolution from BCS to BEC superfluidity in the presence of spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. A 2012, 85, 011606(R). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Gong, M.; Zhang, C. BCS-BEC crossover in spin-orbit-coupled two-dimensional Fermi gases. Phys. Rev. A 2012, 85, 013601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Zhang, Z. Opposite effect of spin-orbit coupling on condensation and superfluidity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 025301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Wan, S. Phase diagram of a uniform two-dimensional Fermi gas with spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. A 2012, 85, 023633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iskin, M. Vortex line in spin-orbit coupled atomic Fermi gases. Phys. Rev. A 2012, 85, 013622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, K.; Han, L.; de Melo, C.A.R.S. Topological phase transitions in ultracold Fermi superfluids: The evolution from Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer to Bose-Einstein-condensate superfluids under artificial spin-orbit fields. Phys. Rev. A 2012, 85, 033601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Huang, X.-G. BCS-BEC crossover in 2D Fermi gases with Rashba spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 145302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dell’Anna, L.; Mazzarella, G.; Salasnich, L. Tuning Rashba and Dresselhaus spin-orbit couplings: Effects on singlet and triplet condensation with Fermi atoms. Phys. Rev. A 2012, 86, 053632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, P.; Deng, Y. Modified Bethe-Peierls boundary condition for ultracold atoms with spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. A 2012, 86, 053608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, P. Scattering and effective interactions of ultracold atoms with spin-orbit interaction. Phys. Rev. A 2013, 87, 053626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.-X.; Liu, X.-J.; Long, G.L.; Hu, H. Validity of a single-channel model for a spin-orbit-coupled atomic Fermi gas near Feshbach resonances. Phys. Rev. A 2012, 86, 053628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Huang, X.-G. BCS-BEC crossover in three-dimensional Fermi gases with spherical spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. B 2012, 86, 014511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, M.; Chen, G.; Jia, S.; Zhang, C. Searching for Majorana fermions in 2D spin-orbit coupled Fermi superfluids at finite temperature. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 109, 105302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W. Interatomic collisions in two-dimensional and quasi-two-dimensional confinements with spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. A 2012, 86, 042707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Huang, X.G.; Hu, H.; Liu, X.J. BCS-BEC crossover at finite temperature in spin-orbit-coupled Fermi gases. Phys. Rev. A 2013, 87, 053616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Huang, X.G. Superfluidity and collective modes in Rashba spin–orbit coupled Fermi gases. Ann. Phys. 2013, 337, 163–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.F.; Guo, G.C.; Zhang, W.; Yi, W. Exotic pairing states in a Fermi gas with three-dimensional spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. A 2013, 87, 063606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Chen, G.; Jia, S. Spin-orbit-induced bound state and molecular signature of the degenerate Fermi gas in a narrow Feshbach resonance. Phys. Rev. A 2013, 88, 013611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldas, H.; Farias, R.L.S.; Continentino, M. Influence of induced interactions on superfluid properties of quasi-two-dimensional dilute Fermi gases with spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. A 2013, 88, 023615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Guo, G.-C.; Zhang, W.; Yi, W. Unconventional superfluid in a two-dimensional Fermi gas with anisotropic spin-orbit coupling and Zeeman fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 110, 110401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Guo, G.-C.; Zhang, W.; Yi, W. Unconventional Fulde-Ferrell-Larkin-Ovchinnikov pairing states in a Fermi gas with spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. A 2013, 88, 043614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-J.; Law, K.T.; Ng, T.K.; Lee, P.A. Detecting topological phases in cold atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 111, 120402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salasnich, L. Two-dimensional quasi-ideal Fermi gas with Rashba spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. A 2013, 88, 055601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yi, W. Topological Fulde–Ferrell–Larkin–Ovchinnikov states in spin–orbit-coupled Fermi gases. Nature Comm. 2013, 4, 2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Zhou, K.; Liu, W.; Liang, Z.; Zhang, Z. Fidelity susceptibility and topological phase transition of a two-dimensional spin-orbit-coupled Fermi superfluid. Phys. Rev. A 2014, 89, 043612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Zhang, R.; Deng, T.-S.; Zhang, W.; Yi, W.; Guo, G.-C. BCS-BEC crossover and quantum phase transition in an ultracold Fermi gas under spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. A 2014, 89, 063610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Cui, X.; Yi, W. Three-component ultracold Fermi gases with spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 112, 195301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, H. Degenerate quantum gases with spin–orbit coupling: A review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2015, 78, 026001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devreese, J.P.A.; Tempere, J.; de Melo, C.A.R.S. Quantum phase transitions and Berezinskii-Kosterlitz-Thouless temperature in a two-dimensional spin-orbit-coupled Fermi gas. Phys. Rev. A 2015, 92, 043618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-K.; Yi, W.; Zhang, W. Two-body physics in quasi-low-dimensional atomic gases under spin–orbit coupling. Front. Phys. 2016, 11, 118102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, D.-H. Induced interactions in the BCS-BEC crossover of two-dimensional Fermi gases with Rashba spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. A 2017, 95, 033609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koinov, Z.; Pahl, S. Spin-orbit-coupled atomic Fermi gases in two-dimensional optical lattices in the presence of a Zeeman field. Phys. Rev. A 2017, 95, 033634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazziotti, M.V.; Valletta, A.; Raimondi, R.; Bianconi, A. Multigap superconductivity at an unconventional Lifshitz transition in a three-dimensional Rashba heterostructure at the atomic limit. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 103, 024523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiyanov, K.; Makhalov, V.; Turlapov, A. Observation of a two-dimensional Fermi gas of atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 030404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perali, A.; Pieri, P.; Strinati, G.C. Quantitative comparison between theoretical predictions and experimental results for the BCS-BEC crossover. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 93, 100404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, R.; Ovchinnikov, M.W.A.Y.B. Optical dipole traps for neutral atoms. Adv. At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 2000, 42, 95–170. [Google Scholar]

- Inguscio, M.; Ketterle, W.; Salomon, C. Ultra-Cold Fermi Gases, Proceedings of the International School of Physics “Enrico Fermi”, Course CLXIV; IOS Press: Varenna, Como, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pethick, C.J.; Smith, H. Bose-Einstein Condensation in Dilute Gases; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ketterle, W.; Druten, N.J.V. Evaporative cooling of trapped atoms. Adv. At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 1996, 37, 181–236. [Google Scholar]

- Landau, L.D.; Lifshitz, E.M. Quantum Mechanics: Non-relativistic Theory; Course Theoretical Physics Volume 3; Pergamon Press Ltd: Oxford, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, J.R. Scattering Theory: The Quantum Theory of Nonrelativistic Collisions; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Stoof, H.T.C.; Dickerscheid, D.B.M.; Gubbels, K. Ultracold Quantum Fields; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Parish, M.M.; Marchetti, F.M.; Lamacraft, A.; Simons, B.D. Finite temperature phase diagram of a polarised Fermi condensate. Nature Phys. 2007, 3, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheey, D.; Radzihovsky, L. BEC–BCS crossover, phase transitions and phase separation in polarized resonantly-paired superfluids. Ann. Phys. 2007, 322, 1790–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perali, A.; Pieri, P.; Strinati, G.C.; Castellani, C. Pseudogap and spectral function from superconducting fluctuations to the bosonic limit. Phys. Rev. B 2002, 66, 024510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Stajic, J.; Tan, S.; Levin, K. BCS–BEC crossover: From high temperature superconductors to ultracold superfluids. Phys. Rep. 2005, 412, 1–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palestini, F.; Perali, A.; Pieri, P.; Strinati, G.C. Dispersions, weights, and widths of the single-particle spectral function in the normal phase of a Fermi gas. Phys. Rev. B 2012, 85, 024517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khelashvili, A.A.; Nadareishvili, T.P. What is the boundary condition for the radial wave function of the Schrödinger equation? Am. J. Phys. 2011, 79, 668–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dell’Anna, L.; Grava, S. Critical Temperature in the BCS-BEC Crossover with Spin-Orbit Coupling. Condens. Matter 2021, 6, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/condmat6020016

Dell’Anna L, Grava S. Critical Temperature in the BCS-BEC Crossover with Spin-Orbit Coupling. Condensed Matter. 2021; 6(2):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/condmat6020016

Chicago/Turabian StyleDell’Anna, Luca, and Stefano Grava. 2021. "Critical Temperature in the BCS-BEC Crossover with Spin-Orbit Coupling" Condensed Matter 6, no. 2: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/condmat6020016

APA StyleDell’Anna, L., & Grava, S. (2021). Critical Temperature in the BCS-BEC Crossover with Spin-Orbit Coupling. Condensed Matter, 6(2), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/condmat6020016