Unveiling the Role of Graphene in Enhancing the Mechanical Properties of Electrodeposited Ni Composites

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Result and Discussion

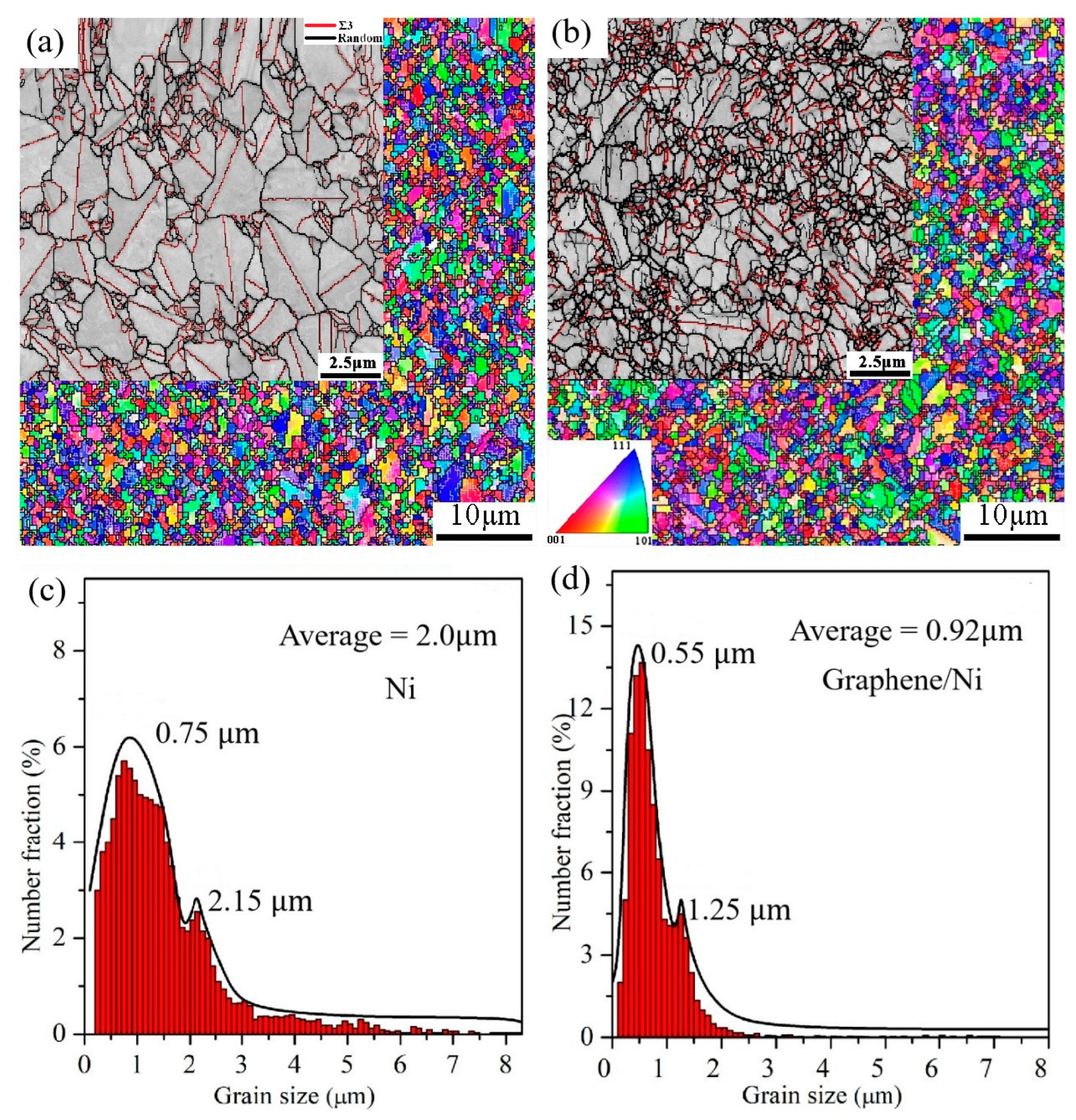

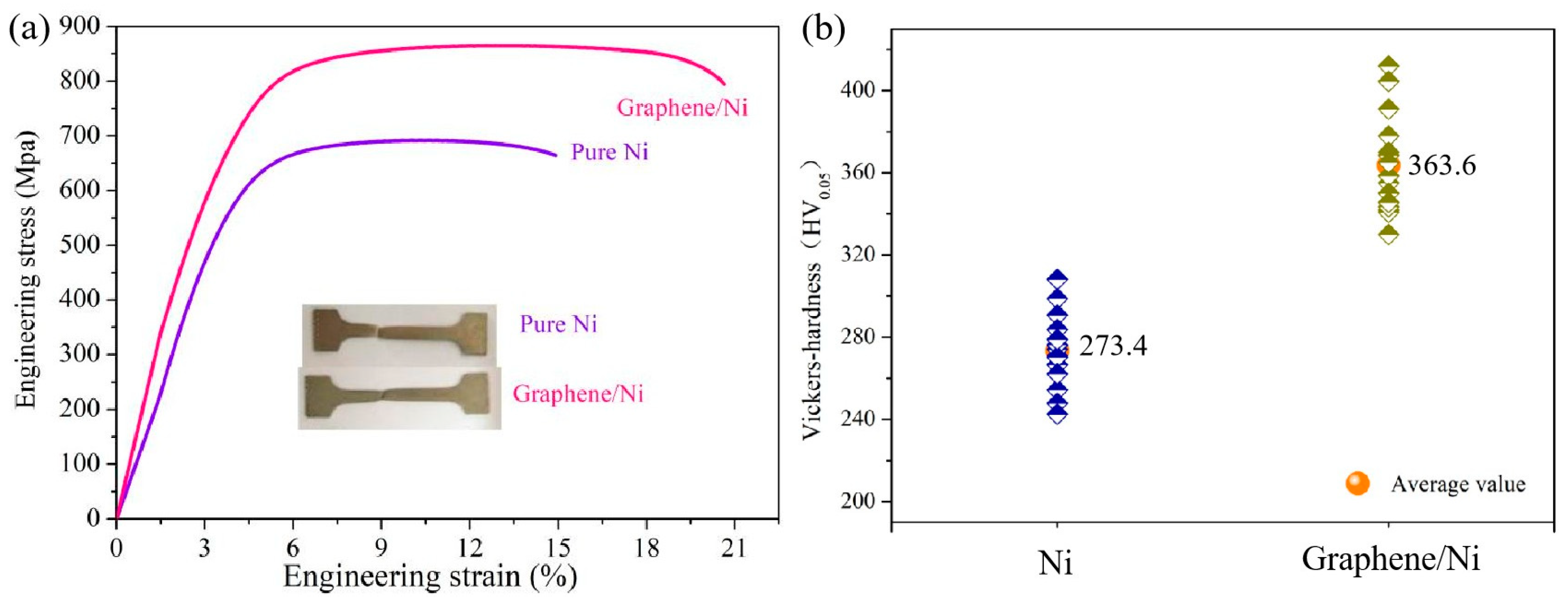

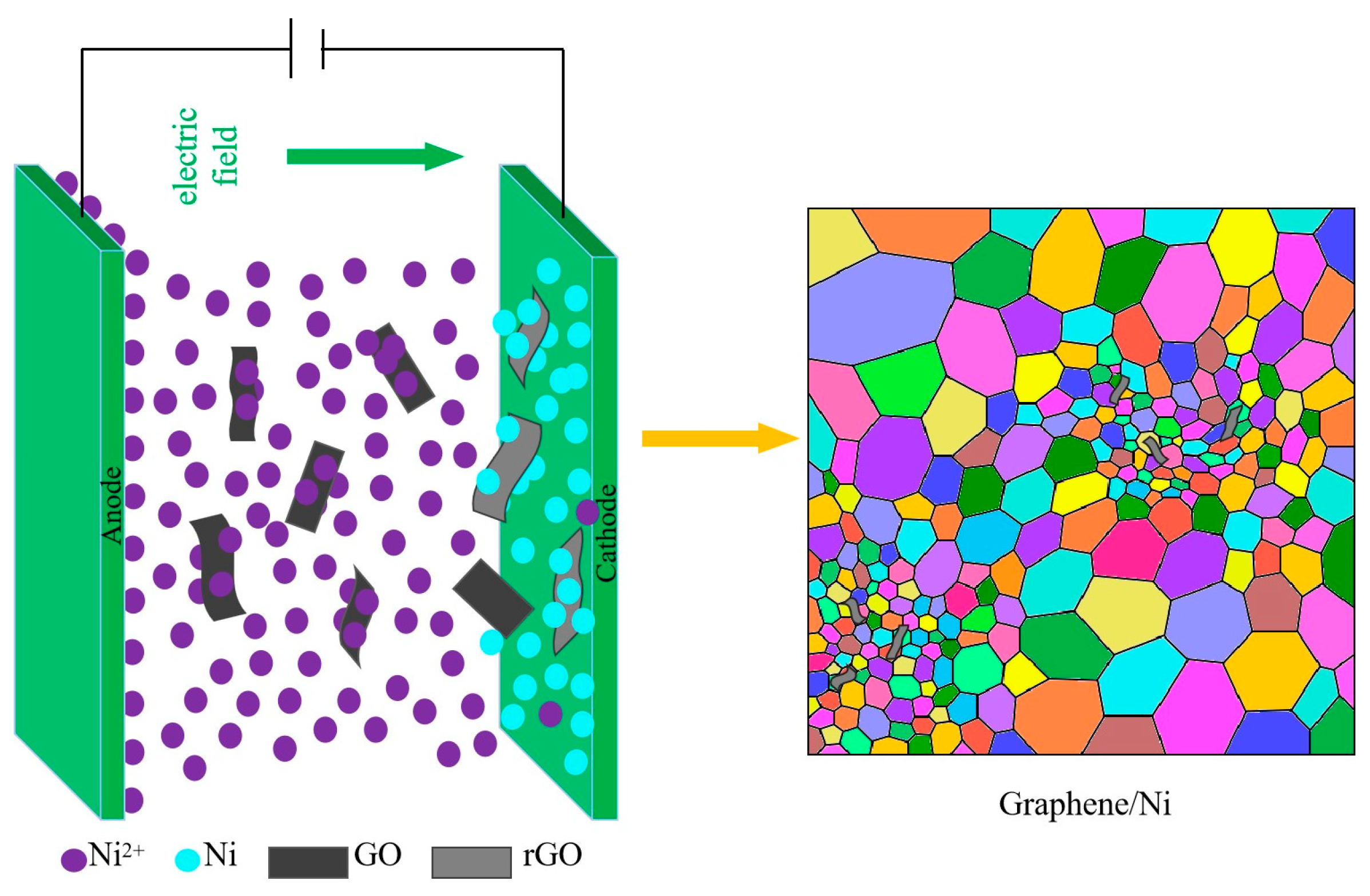

2.1. Mechanism of Microstructure Evolution and Mechanical Property Analysis

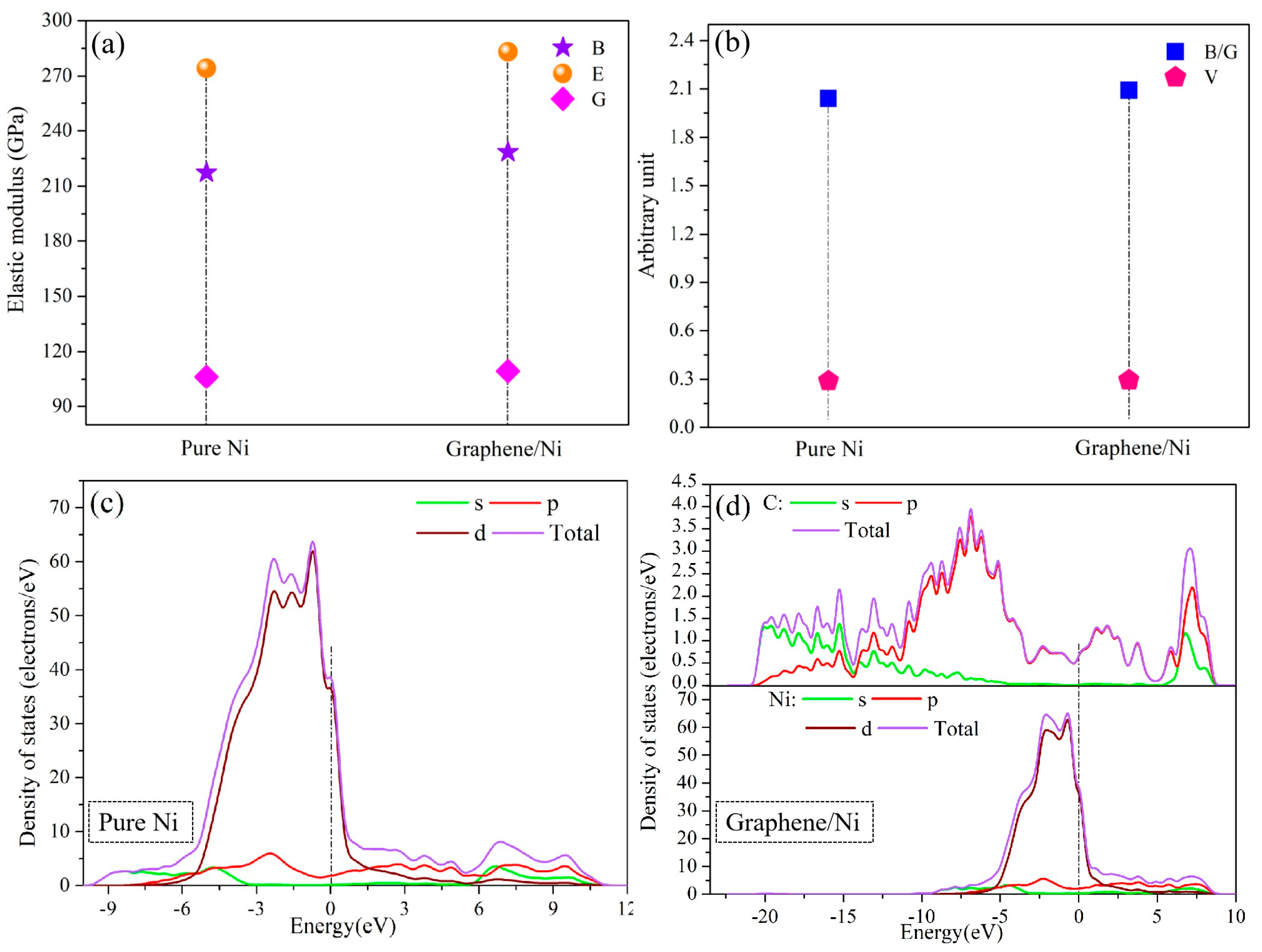

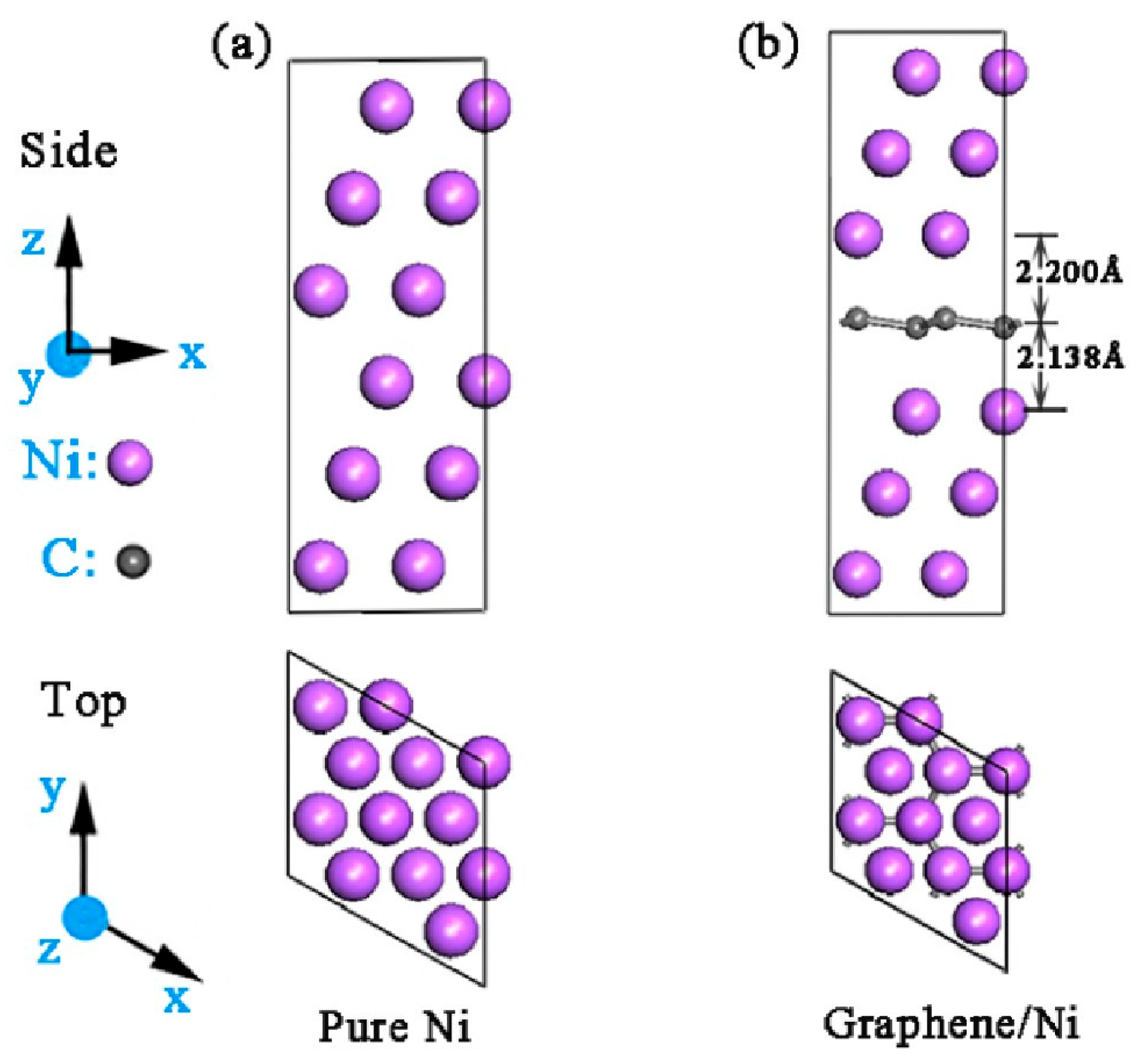

2.2. DFT Analysis

3. Methods

3.1. Computational Method

3.2. Experimental Section

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rohatgi, P.K.; Asthana, R.; Das, S. Solidification, structures, and properties of cast metal-ceramic particle composites. Int. Met. Rev. 1986, 31, 115–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alem, S.A.A.; Sabzvand, M.H.; Govahi, P.; Poormehrabi, P.; Azar, M.H.; Siouki, S.S.; Rashidi, R.; Angizi, S.; Bagherifard, S. Advancing the next generation of high-performance metal matrix composites through metal particle reinforcement. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2025, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, S. Design and Development of Metal Matrix Composites. Metals 2025, 15, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, J.B.; Thao, X.; Rohatgi, P.K.; Cho, K.; Kim, C.S. Computational and analytical prediction of the elastic modulus and yield stress in particulate-reinforced metal matrix composites. Scr. Mater. 2014, 83, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Wei, X.; Kysar, J.W.; Hone, J. Measurement of the elastic properties and intrinsic strength of monolayer graphene. Science 2008, 321, 385–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokrieh, M.M.; Rafiee, R. Prediction of Young’s modulus of graphene sheets and carbon nanotubes using nanoscale continuum mechanics approach. Mater. Des. 2010, 31, 790–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadam, A.D.; Omrani, E.; Menezes, P.L.; Rohatgi, P.K. Mechanical and tribological properties of self-lubricating metal matrix nanocomposites reinforced by carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and grapheme-a review. Compos. Part B 2015, 77, 402–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, J.; Liao, T.; Ayoko, G.A.; Bell, J.; Sun, Z. Cobalt oxide-based nanoarchitectures for electrochemical energy applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2019, 103, 596–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, A.; Bisht, A.; Lahiri, D.; Zhang, C.; Agarwal, A. Graphene reinforced metal and ceramic matrix composites: A review. Int. Mater. Rev. 2016, 62, 241–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banhart, F.; Charlier, J.C.; Ajayan, P.M. Dynamic Behavior of Nickel Atoms in Graphitic Networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 84, 686–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lajevardi, S.A.; Shahrabi, T. Effects of pulse electrodeposition parameters on the properties of Ni–TiO2 nanocomposites coatings. Appl. Sur. Sci. 2010, 256, 6775–6781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Guo, X.; Bribillis, N.; Wu, G.; Ding, W. Tailoring nickel coatings via electrodeposition from a eutectic-based ionic liquid doped with nicotinic acid. Appl. Sur. Sci. 2011, 257, 9094–9102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnik, E.; Burzynska, L.; Dolasinski, L.; Misiak, M. Electrodeposition of nickel/SiC composites in the presence of cetyltrimethylammonium bromide. Appl. Sur. Sci. 2012, 256, 7414–7420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.K.; Pritschow, A.; Flewitt, J.; Spearing, S.M.; Fleck, N.A.; Milne, W.I. Effects of process conditions on properties of electroplated Ni thin films for microsystem applications. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2006, 153, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Nabb, D.; Renevier, N.; Sherrington, I.; Fu, Y.Q.; Luo, J.K. Mechanical and anti-corrosion properties of TiO2 nanoparticle reinforced Ni coating by electrodeposition. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2012, 159, 671–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Qu, Z.; Yang, J.; Zheng, M.; Zhai, S.; Zhu, S. Production of ZnAlFeO4 spinel through pyrometallurgical treatment of electroplating sludge: Growth and stabilization process of spinel. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 115637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, A.; Escudero-Cid, R.; Ocón, P.; Fatás, E. Effect of the pulse plating parameters on the mechanical properties of nickel. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2012, 212, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Wang, J.; Engelhard, M.; Wang, C.; Lin, Y. Facile and controllable electro-chemical reduction of graphene oxide and its applications. J. Mater. Chem. 2010, 20, 743–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.J.; Zhu, Y.; Lee, S.H.; Stoller, M.D.; Emilsson, T.; Park, S.; Velamakanni, A.; An, J.; Ruoff, R.S. Thin film fabrication and simultaneous anodic reduction of deposited graphene oxide platelets by electrophoretic deposition. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2010, 1, 1259–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.L.; Wang, X.F.; Qian, Q.Y.; Wang, F.B.; Xia, X.H. A green approach to the synthesis of graphene nanosheets. ACS Nano 2009, 3, 2653–2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhai, Y.; Zhai, J.; Ren, W.; Wang, F.; Dong, S. Controlled synthesis of large-area and patterned electrochemically reduced graphene oxide films. Chem.-Eur. J. 2009, 15, 6116–6120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagannadham, K. Electrical conductivity of copper-graphene composite films synthesized by electrochemical deposition with exfoliated graphene platelets. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 2012, 43, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, D.; Xu, L.; Liu, L.; Hu, W.; Wu, Y. Graphene—Nickel composites. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2013, 273, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Pan, L.; Lv, T.; Zhu, G.; Lu, T.; Sun, Z.; Sun, C. Microwave-assisted synthesis of TiO2-reduced graphene oxide composites for the photocatalytic reduction of Cr(VI). RSC Adv. 2011, 1, 1245–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, T.; Abdala, A.A.; Stankovich, S.; Dikin, D.A.; Herrera-Alonso, M.; Piner, R.D.; Adamson, D.H.; Schniepp, H.C.; Chen, X.; Ruoff, R.S.; et al. Functionalized graphene sheets for polymer nanocomposites. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2008, 3, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, C.M.P.; Venkatesha, T.V.; Shabadi, R. Preparation and corrosion behavior of Ni and Ni–graphene composite coatings. Mater. Res. Bull. 2013, 48, 1477–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casati, R.; Vedani, M. Metal matrix composites reinforced by nano-particles—A review. Metals 2014, 4, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, G.F.; Liu, S.Y.; Zhao, S.S.; Zhang, K.F. The preparation of Ni/GO composite foils and the enhancement effects of GO in mechanical properties. Compos. Part B Eng. 2018, 135, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavithra, C.L.; Sarada, B.V.; Rajulapati, K.V.; Rao, T.N.; Sundararajan, G. A new electrochemical approach for the synthesis of copper-graphene nanocomposite foils with high hardness. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 4049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, G.F.; Liu, Q.; Yang, M. Ni/GO nanocomposites and its plasticity. Manuf. Rev. 2015, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mishra, R.; Balasubramaniam, R. Effect of nanocrystalline grain size on the electrochemical and corrosion behavior of nickel. Corros. Sci. 2004, 46, 3019–3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, J.; Xue, X.; Li, M.; Sui, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, W.; Lu, C. Dendrite-Free Zn/rGO@CC Composite Anodes Constructed by One-Step Co-Electrodeposition for Flexible and High-Performance Zn-Ion Batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2306346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Guo, P.; Cao, D.; Ma, Y.; Liu, D.; Liu, Q.; Fu, Y.; Liu, J.; He, D. Sheet-Like Stacking SnS2/rGO Heterostructures as Ultrastable Anodes for Lithium-Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 11739–11749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Z.; Liu, J.; Qi, H.; Huang, Z.; Wang, X. RGO-Induced Flower-like Ni-MOF In Situ Self-Assembled Electrodes for High-Performance Hybrid Supercapacitors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 584–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Wu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Li, H.; Xu, M.; Li, J.; Dai, Y.; Zong, W.; Chen, R.; He, L.; et al. Rationally Designed Sodium Chromium Vanadium Phosphate Cathodes with Multi-Electron Reaction for Fast-Charging Sodium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2201065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, R.; Carbone, P.; Wang, F.; Kravets, V.; Su, Y.; Grigorieva, I.; Wu, H.; Geim, A.; Nair, R. Precise and Ultrafast Molecular Sieving Through Graphene Oxide Membranes. Science 2014, 343, 752–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Ma, X.; Niu, B.; Chen, M.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Long, D. General synthesis of ultrafine metal oxide/reducedgraphene oxide nanocomposites for ultrahigh-flux nanofiltration membrane. Nat. Commun. 2022, 1, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Chen, J.; Hou, F.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhong, X.; Song, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, H.; et al. In situ growth-optimized synthesize of Al-MOF@RGO anode materials with long-life capacity-enhanced lithium-ion storage. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 455, 140561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Feng, F.; Liu, S.; Liu, L.; Gao, X. Preparation of Nitrogen and Phosphorus Co-doped Graphene Oxide and Corrosion Resistance of Waterborne Composite Coatings NPGO/Epoxy Resin. Chin. J. Mater. Res. 2024, 38, 861–871. [Google Scholar]

- Samira, M.; Amir, M.; Seyed, M. High-Performance Ni(II)@Amine-Functionalized Graphene Oxide Composite as Supercapacitor Electrode: Theoretical and Experimental Study. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2024, 7, 6142–6154. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, K.; Derré, A.; Puech, P.; Rouzière, S.; Launois, P.; Castro, C.; Monthioux, M.; Pénicaud, A. Conductive graphene coatings synthesized from graphenide solutions. Carbon 2017, 121, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoller, M.D.; Park, S.; Zhu, Y.W.; An, J.H.; Ruoff, R.S. Graphene-based ultracapacitors. Nano Lett. 2008, 10, 3498–3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, C.; Wang, J.; Wu, Y.; Han, P.; Gao, Z.; Wang, L.; Wu, X. Control of the microstructure and mechanical properties of electrodeposited graphene/Ni composite. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 727, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, R.; Mukherjee, S. First-principles study of the electrical and lattice thermal transport in monolayer and bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 2017, 95, 085435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimme, S. Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J. Comput. Chem. 2006, 27, 1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Born, M. On the stability of crystal lattices. Math. Proc. Camb. Philos. Soc. 1940, 36, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.J.; Zhao, E.J.; Xiang, H.P.; Hao, X.F.; Liu, X.J.; Meng, J. Crystal structures and elastic properties of superhard IrN2 and IrN3 from first principles. Phys. Rev. B 2007, 76, 054115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R. The elastic behaviour of a crystalline aggregate. Proc. Phys. Soc. Sect. A 1952, 65, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanovskii, A.L. New superconductors based on (Ca, Sr, Ba) Fe2As2 ternary arsenides: Synthesis, properties, and simulation. J. Struct. Chem. 2009, 50, 539–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Du, L.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, D.; Han, P.; Zhang, Z. Theoretical insight on interface enhancement mechanism and electrocatalytic water splitting reactions using heteroatoms-mediated graphene/Cu composites. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 48, 113306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

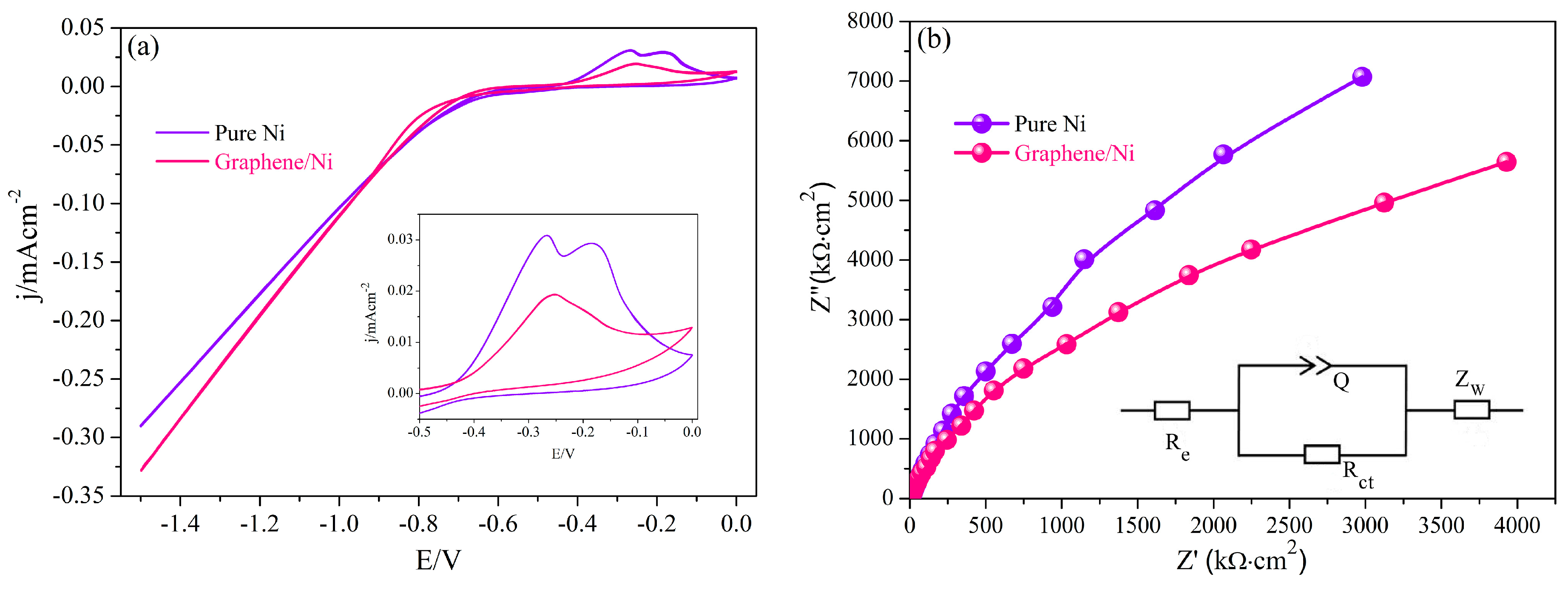

| Materials | Re (Ω·cm2) | Q (Ω−1·sn·cm−2) | n | Rct (kΩ·cm2) | Zw (Ω·cm2·S−1/2) | Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni | 76.5 | 1.0 × 10−4 | 0.941 | 341 | 2.01 × 10−3 | 0.51 |

| Graphene/Ni | 63.2 | 1.01 × 10−4 | 0.927 | 14.8 | 3.32 × 10−3 | 1.52 |

| Cij | Single-Crystal Elastic Constants (GPa) | Stability | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | ||

| C1 | 384.3 | 147.6 | 118.7 | 0 | −34.7 | −7.0 | Yes |

| C2 | 147.6 | 396.2 | 119.0 | 0 | 35.1 | −2.4 | |

| C3 | 118.7 | 119.0 | 405.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| C4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 91.9 | 0 | 34.8 | |

| C5 | −34.7 | 35.1 | 0 | 0 | 90.2 | 0 | |

| C6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 34.8 | 0 | 118.5 | |

| Cij | Single-Crystal Elastic Constants (GPa) | Stability | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | ||

| C1 | 503.2 | 146.6 | 108.4 | −0.4 | −15.5 | −8.9 | Yes |

| C2 | 146.6 | 515.8 | 109.8 | −1.2 | 15.4 | −2.4 | |

| C3 | 108.4 | 109.8 | 350.1 | 0.5 | −1.1 | −2.0 | |

| C4 | −0.4 | −1.2 | 0.5 | 57.5 | 0.8 | 16.7 | |

| C5 | −15.5 | 15.4 | −1.1 | 0.8 | 58.1 | −0.8 | |

| C6 | −8.9 | −2.4 | −2.0 | 16.7 | −0.8 | 178.4 | |

| Current density (A/dm2) | 0.14 | 0.35 | 0.52 | 0.70 | 0.86 | 1.12 | 1.27 | 1.44 |

| Cathode current efficiency ŋ | 75.5 | 68.5 | 60.5 | 72.3 | 78.0 | 72.4 | 60.3 | 61.6 |

| Deposition time (h) | 32 | 24 | 19 | 15 | 13 | 10 | 8 | 9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, B.; Zhu, J.; Yuan, Z.; Han, P. Unveiling the Role of Graphene in Enhancing the Mechanical Properties of Electrodeposited Ni Composites. Condens. Matter 2025, 10, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/condmat10040063

Zhang B, Zhu J, Yuan Z, Han P. Unveiling the Role of Graphene in Enhancing the Mechanical Properties of Electrodeposited Ni Composites. Condensed Matter. 2025; 10(4):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/condmat10040063

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Bingqian, Junhao Zhu, Zhihua Yuan, and Peide Han. 2025. "Unveiling the Role of Graphene in Enhancing the Mechanical Properties of Electrodeposited Ni Composites" Condensed Matter 10, no. 4: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/condmat10040063

APA StyleZhang, B., Zhu, J., Yuan, Z., & Han, P. (2025). Unveiling the Role of Graphene in Enhancing the Mechanical Properties of Electrodeposited Ni Composites. Condensed Matter, 10(4), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/condmat10040063