Abstract

Traditional fish farming methods suffer from backward production, low efficiency, low yield, and environmental pollution. As a result of thorough research using deep learning technology, the industrial aquaculture model has experienced gradual maturation. A variety of complex factors makes it difficult to extract effective features, which results in less-than-good model performance. This paper proposes a fish detection method that combines a triple attention mechanism with a You Only Look Once (TAM-YOLO)model. In order to enhance the speed of model training, the process of data encapsulation incorporates positive sample matching. An exponential moving average (EMA) is incorporated into the training process to make the model more robust, and coordinate attention (CA) and a convolutional block attention module are integrated into the YOLOv5s backbone to enhance the feature extraction of channels and spatial locations. The extracted feature maps are input to the PANet path aggregation network, and the underlying information is stacked with the feature maps. The method improves the detection accuracy of underwater blurred and distorted fish images. Experimental results show that the proposed TAM-YOLO model outperforms YOLOv3, YOLOv4, YOLOv5s, YOLOv5m, and SSD, with a mAP value of 95.88%, thus providing a new strategy for fish detection.

Keywords:

YOLOv5s; attention mechanism; coordinate attention; convolutional block attention module; fish detection Key Contribution:

The proposed TAM-YOLO model enhances the YOLO framework with a triple attention mechanism, improving the accuracy and robustness of fish detection in various environmental conditions.

1. Introduction

With the advent of smart fishery [1] and precision farming [2], fish farming is tending toward industrialization [3]. However, the industrial farming model has the problem of low automation. Fish detection is a prerequisite for the realization of intelligent aquaculture [4]. The positioning data obtained from fish detection can provide support for the subsequent analysis of fish tracking behavior. The number of detection frames obtained by fish detection can reflect the aggregation of fish at the current moment, and the indicator of aggregation is one of the important criteria for analyzing fish activity and realizing intelligent feeding systems. Fish size data can be obtained from fish detection, which makes a significant contribution to the real-time monitoring of fry growth. The main difficulties of the fish detection algorithm follow.

- (1)

- Experimental data collection has problems, such as uneven illumination, the turbidity of the water environment, obstruction of underwater cameras, and shooting angles. As a result, the collected data cannot provide sufficient information to match the target, thus resulting in unstable and inconsistent target detection.

- (2)

- With changes in fish aggregation, the obscured area between the fish also changes, which presents a challenge to detection performance.

This article has five parts. Section 1 describes the application of computer vision in fisheries and summarizes work related to traditional and deep learning fish detection algorithms. Section 2 describes the construction method of the You Only Look Once (YOLOv5s) network with a triple attention mechanism. Section 3 builds the dataset, sets the model hyperparameters, and evaluates the method. Section 4 discusses the ablation experiments and experimentally compares model performance. Section 5 relates our conclusions and discusses future research work.

2. Related Work

In the process of fish farming, it is necessary to pay close attention to various elements. The slightest carelessness can cause irreparable losses and increase the risks and costs. In the past, these problems were difficult to solve due to technological limitations. However, with computer vision technology, equipment can be relied on to automate the management and control of these elements, reducing risks and costs, and intelligent fish farming is becoming a trend [5].

Research on fish identification has produced many results, such as appearance identification, classification, density estimation, body length measurement, and healthy growth monitoring [6]. Identification algorithms have developed from traditional to deep learning-based, a good research ecology has been formed, and accurate fish detection pairs are the basis of the fish identification task [7]. This is helpful for research on fish activity analysis, disease diagnosis, and feeding behavior.

The development of traditional vision algorithms and deep learning algorithms has promoted the research of fish detection algorithms. Traditional visual algorithms, such as color feature extraction [8], texture feature extraction [9], geometric feature extraction [10], and other methods, combined with the experience of fish keepers [11], use a classifier to process fish targets. When the fish aggregation degree is small and the artificially designed extractor conforms to the specific feeding situation, the detection accuracy is higher [12]. However, with a high degree of fish aggregation, the increase in fish species, and the change of the fish locus caused by external factors, the detection accuracy will be reduced, and the robustness of the model will be low.

With the development of deep learning algorithms in underwater biometrics [4], the model can automatically extract effective features according to the actual image of fish farming and constantly adjust weights to realize strong robustness.

A deep learning algorithm has two stages. The second stage is represented by models such as R-CNN [13], with high detection accuracy and slow speed. Zhao et al. [14] proposed an unsupervised adversarial domain-adaptive fish detection model based on interpolation that combines Faster R-CNN and three adaptive modules to achieve cross-domain detection of fish in different aquaculture environments. Mathur et al. [15] proposed a method for fish species classification in underwater images based on migrating ResNet-50 weight-optimized convolutional neural networks. In order to achieve fish identification and localization in complex underwater environments, Zhao et al. [16] proposed a fish detection method based on a composite backbone and enhanced path aggregation network by improving the residual network (ResNet) and path aggregation network.

The single stage is represented by models such as YOLO [17], with a fast detection speed and lower detection accuracy. To solve the problem of finding the location of dead fish in the real environment, Yu et al. [18] proposed a dead fish detection method based on SSD-MobileNet on the water surface. Zhao et al. [19] improved a high-precision and lightweight end-to-end target detection model based on deformable convolution and improved YOLOv4. Wang et al. [20] proposed a YOLOv5 diseased fish detection model with a C3 structure for the backbone network and improved with a convolutional attention module. Wang et al. [21] improved YOLOv5s to provide location information for fish anomaly analysis. To solve the problem of a low recognition rate due to high aggregation of underwater organisms, Li et al. [22] proposed CME-YOLOv5L, which introduces a CA attention mechanism to YOLOv5L to improve the loss function; this is better for dense fish detection. Li et al. [23] proposed DCM-ATM-YOLOv5X, which uses a deformable convolution module (DCM) to extract fish features and an adaptive threshold module (ATM) to detect fish occlusion in Takifugu rubripes, but it still had a manually set threshold of 0.5. Zhao Meng et al. [24] proposed a farmed fish detection SK-YOLOv5x model that fuses the SKNet (selective kernel networks) visual attention mechanism with YOLOv5x to form a feature extraction network focusing on pixel-level information, which enhances the recognition of fuzzy fish bodies. The model somewhat improves detection accuracy, but it requires more model parameters, and the single fish species being detected differs significantly from the background. Thus, the model should also be available considered for use in practical detection. To handle multiple fish recognition in a single image in real time, Han et al. [25] proposed a group behavior discrimination method based on a convolutional neural network and spatiotemporal information fusion, which can effectively identify and classify the normal state, group stimulation state, individual disturbance state, and feeding state of fish. In Alaba et al. [26], a backbone network was proposed as MobileNetv3-large combined with an SSD detection head. It used the class-aware loss function to deal with the class imbalance problem. Automatic fish detection will help realize intelligent production and scientific management of precision farming [27].

To achieve the accurate detection of fish targets in an environment similar to the background, we propose a zebrafish school detection method that integrates the triple attention mechanism with YOLOv5s. The method can provide rich theoretical data for the intelligent monitoring of fish swarms.

We make the following contributions: (1) The pretraining weights of the VOC dataset are migrated, positive sample matching is incorporated in the data encapsulation process, and the exponential moving average (EMA) [28] is added to the model training process. (2) To extract effective features, we improve the structure of the YOLOv5s network. Coordinate attention (CA) [29] and a convolutional block attention module (CBAM) [30] are integrated into the YOLOv5s backbone to form a coordinate–channel–space chain attention model, and the attention network model parameters are fine-tuned for the extraction of more effective and accurate features.

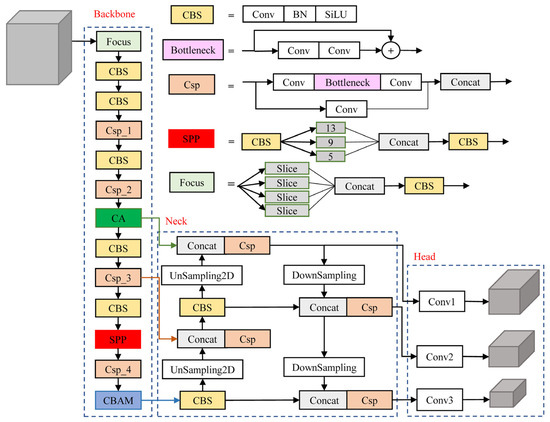

3. The YOLOv5s Network with Triple Attention Mechanism

The YOLOv5 series includes four models with the same main network structure but use different width and depth parameters: s (depth 0.33, width 0.5), m (depth 0.67, width 0.75), l (depth 1, width 1), and x (depth 1.33, width 1.25). We select YOLOv5s as the basic model when performing fish image detection experiments, taking into account the detection accuracy and detection speed of the model [31]. We aim to improve the detection accuracy of YOLOv5s and reduce the influence of background interference. The encoder-decoder structure of the path aggregation network (PANet) is based on the characteristics of output feature maps of different layers of the backbone feature extraction network, and the enhanced feature information of different layers is integrated. By fusing CA and CBAM into the Csp_2 layer and Csp_4 layer of the YOLOv5s backbone, it can focus on the fish area and suppress interference. The model structure is shown in Figure 1; see Section 3.2 and Section 3.3 of this paper for a detailed discussion of the triple attention mechanism.

Figure 1.

YOLOv5s network with triple attention mechanism.

We integrated positive sample matching in the data encapsulation process and adopted the EMA and Mosaic data enhancement in model training. The backbone of TAM-YOLO is a feature extraction network, which consists of Focus, CSP, SPP, CBS, CA, and CBAM structures for feature extraction. Three effective feature layers, Feature1 (80 × 80 × 128), Feature2 (40 × 40 × 256), and Feature3 (20 × 20 × 512), are output. The neck of TAM-YOLO is a PANet for enhanced feature extraction, which integrates feature information of different scales by up–down sampling of Feature1, Feature2, and Feature3. The head of TAM-YOLO is used to judge whether objects correspond to the feature points.

3.1. Exponential Moving Average

The EMA smooths the model weights, which can result in better generalization. The calculation formulas are shown in Equation (1) [28], where is the EMA weight, generally also known as the shadow weight, and is the recession rate, generally taking a number close to 1, such as 0.999 or 0.9999. This keeps the shadow weight from changing drastically and always moving slowly around the optimal weight. is the model weight.

The shadow weights are accumulated by the weighted average of the historical model weight indices. Each shadow weight update is influenced by the previous shadow weight, so the shadow weights are updated with the inertia of the previous model weights. The older the historical weights are, the less important they are, which can make weight updates smoother [28].

In this paper, the α decay rate was selected as 0.9999. The value of the EMA is stored in the last storage model, and the approximate average of the last n times is taken to realize better performance indicators and stronger generalization.

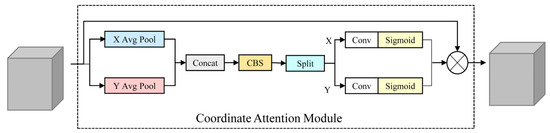

3.2. Coordinate Attention Module

While extracting channel information, the CA mechanism performs one-dimensional feature encoding that is based on width or height. It first integrates the feature space position information, and then it aggregates the features in two directions. The long-term dependencies are obtained in one direction, and accurate coordinate information is obtained in the other direction, thus forming a pair of direction-aware and position-sensitive features. The CA module is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Coordinate attention module.

The CA module is added after the Csp_2 layer of the YOLOv5s backbone. To preserve the spatial structure information, the input, F (80 × 80 × 128), is globally pooled based on width or height, and a pair of one-dimensional feature codes obtains two feature maps (80 × 1 × 128 and 1 × 80 × 128). The features of the aggregated two directions are spliced to obtain a feature map with both channel and spatial information, and a series of transformations are performed to obtain f(c·r)×1×(H+W), where r is 0.3, and ∂ is the sigmoid activation function. The calculation formulas are shown in Equations (2)–(4).

f(c·r)×1×H and f(c·r)×1×W are obtained by separating f(c·r)×1×(H+W) based on width or height, and then the features in the two directions are upgraded. Fh and Fw, with the same size as the original input F (80 × 80 × 128), are output. After passing through the activation function, the attention weights, gh and gw, of the feature map for the height and width, respectively, are obtained. The CA feature is obtained by multiplying the features of the two dimensions by the original feature image. The calculation formulas are shown in Equations (5)–(7) below.

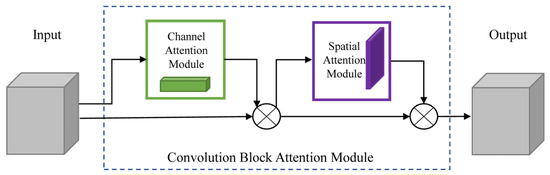

3.3. Convolution Block Attention Module

The convolution block attention mechanism forms an attention map in the channel and space dimensions in turn, and it performs element-wise multiplication of the attention map and feature map input from their respective dimensions, thus extracting a more effective feature structure. The CBAM module is added after the Csp_4 layer of the YOLOv5s backbone. The spatiotemporal attention module is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Convolution block attention module.

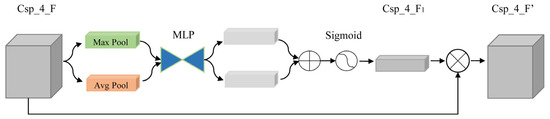

- (1)

- Channel Attention Module

For the input Csp_4_F (20 × 20 × 512) channel number 512, the different pooling operations of global max pooling and global avg pooling are used to obtain two 1 × 1 × 512 richer high-level features, which are then input to the MLP (the number of neurons in the first layer is 32, while the number of neurons in the second layer is 512). We obtain two weights, and . We stack them to obtain the channel and space dual weights, and the channel attention map Csp_4_F1 is obtained through the activation function. The active function calculation formula is shown in Equation (8). The channel attention module is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Channel attention module.

- (2)

- Spatial Attention Module

First, we input the result of bitwise multiplication of Csp_4_F1 and Csp_4_F (20 × 20 × 512) to global max pooling and global avg pooling based on channel 512 to obtain two 20 × 20 × 1 features. Second, we concatenate the two features (20 × 20 × 2). Finally, the spatiotemporal attention map Csp_4_F2 is obtained through a series of operations of convolution, activation, and bitwise multiplication with Csp_4_F’. The spatiotemporal attention map calculation formula is shown in Equation (9). The spatial attention module is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Spatial attention module.

CA extracts the location information of the target, global features, and feature dependencies, thus forming the basis for subsequent extraction of key fish population features. Spatiotemporal attention is divided into channel and spatial attention, which extracts local features and can extract the overall features of the fish population over a period of time. If the global features are extracted by the CA mechanism alone, or if the local features are extracted by the spatiotemporal attention alone, the features extracted by the spatiotemporal attention mechanism will be missing global features, and the features extracted by the CA mechanism will be missing local feature details when the feature fusion stage is carried out. In addition, this process is slower than extracting local detail features based on the global features, and it cannot be used to directly select the required information. Therefore, we first use the global features extracted by the CA mechanism and then use the spatiotemporal attention mechanism for local detail feature extraction, which can extract more effective and critical features. In addition, it can effectively avoid the loss of some information as compared first with the scheme of the spatiotemporal attention mechanism and then with the CA mechanism (local first, and then global).

4. Model Training

4.1. Dataset Preparation

The zebrafish, as a model animal, has been widely used in the research of farmed fish. During the swimming process of fry, they are easy to gather and block, and their morphology changes greatly. Some fish bodies have the same color as the breeding environment, which makes it a great challenge to accurately detect fish fry in a real breeding environment [32]. The experimental data came from zebra fry with a length of 0.5–1.5 cm raised in a glass tank. Fish school images in a real breeding scene were taken by a mobile phone camera facing the glass tank every 5 s. LabelImg software v1.8.2 was used to label the data. Through basic image processing methods, such as rotation, flipping, and cutting, 692 items of experimental data were obtained, with a total of 15,081 fish fry. The random division ratio of the training, validation, and test sets was 5:1:1. The operations of the experimental data are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Image processing: (a) original, (b) flipped, (c) cropped.

4.2. Hyperparameter Settings

The method is based on the YOLOv5s network model, and the model parameters are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Model parameters.

The experimental environment is Linux, PyTorch is the GPU 1.2 version, and TITAN RTX GPU is used for training. When the YOLOv5s network integrating the triple attention mechanism is trained, some parameters are set as follows: In the training process, the input image is normalized to 640 × 640 × 3, and the pre-training weight of the VOC dataset is migrated. First, the trunk network training is frozen to 50 epochs, the batch size is 16, and then the trunk network training is frozen to 100 epochs, with a batch size of 8. Mosaic data enhancement is used in training, but it will be turned off at the 70th epoch of unfreezing training. The maximum learning rate of the model is 1 × 10−2, and the minimum learning rate is 0.01 times the maximum learning rate. The learning rate decay strategy is cos.

4.3. Evaluation Criteria

In this study, the mean average precision (mAP), precision rate, and recall rate of the test set were evaluated under the premise that IoU was 0.5. Precision is the probability of successfully detecting a fish target among all the detected targets. Recall refers to the probability of being successfully detected as a fish among the detected fish targets. Average precision (AP) is a plot ofa P-R curve with recall as the horizontal axis and accuracy as the vertical axis. The result is obtained by integrating this curve, that is, calculating the area between the curve and the coordinate axis. mAP is averaged over the APs of the C categories. where TP (True Positives) is correctly located as the detection result of fish, FP (False Positives) is incorrectly detected as the result of fish, and FN (False Negatives) is not located as the detection result of fish. The calculation formula is as follows:

5. Analysis of Experimental Results

Ablation Experiment

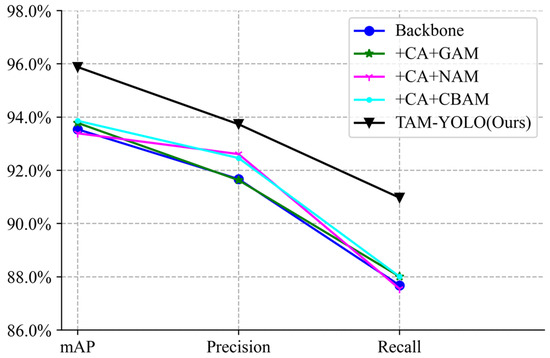

The YOLOv5s backbone has four CSP layers. By comparing and integrating different single attention mechanisms and mixed attention mechanisms, and fine-tuning the model parameters, the effectiveness of the proposed triple attention mechanism model was verified.

By comparing the Csp_2, Csp_3, and Csp_4 layers of the YOLOv5s backbone with a single attention mechanism, global attention mechanism (GAM) [33], CBAM, normalization-based attention (NAM) [34], and CA, the best integration model can be found. The experimental results show that the CA model is integrated after the Csp_2 layer, and the CBAM, NAM, and GAM models are integrated after the Csp_4 layer, which is an improvement over the other models. An experiment involving the mixed attention mechanism is carried out, and the results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

The impact of different single attention mechanisms on model performance. The best results are underlined.

The CA model was added after the Csp_2 layer in the backbone of YOLOv5s, and the GAM model was added after the Csp_4 layer (designated model 2). Then, the CA model was added after the Csp_2 layer in the backbone, and the NAM model was added after the Csp_4 layer (model 3). In addition, the CA model was added after the Csp_2 layer in the backbone, and the NAM model was added after the Csp_4 layer (model 4). Model 4 was selected as the base model by comparing the performances of models 1–4. Model 4 has a 0.79% increase in precision and 0.33% increase in recall compared to model 1, a 0.83% increase in precision compared to model 2, and a 0.85% increase in precision and 0.46% increase in recall compared to model 3.

On the basis of model 4, the positive sample matching process was integrated into the data encapsulation process, and the weight of the EMA model was improved. The excitation factor, r, of the CBAM is 16, and the excitation factor, r, of the CA is 0.3 (model 5). The proposed model 5 improves by 2.34%, 2.1%, 2.49%, and 2.02%, respectively, compared to the mAP of models 1–4. The results are shown in Table 3 and Figure 7.

Table 3.

The impact of hybrid attention mechanism on model performance. The best results are underlined (The numbers 1–5 in the table represent different models).

Figure 7.

Ablation experiment comparison.

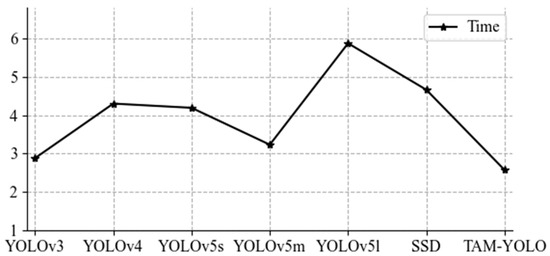

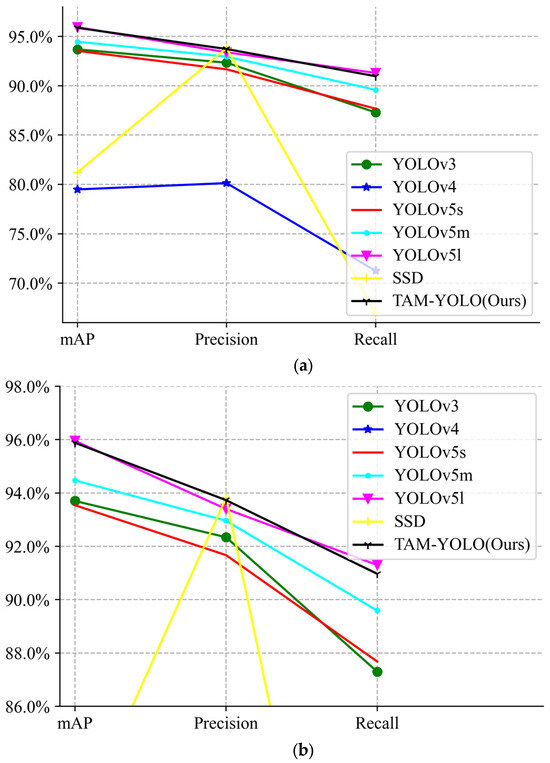

The mAP of the model in this paper is improved by 2.18%, 16.54%, 2.34%, and 1.41% compared to the YOLOv3, YOLOv4, YOLOv5s, and YOLOv5m models, respectively. Our model detects an HD image with a resolution of 1214 × 800 at a speed of 2.57/s, which is faster than the other models. The Yolov4 model does not perform well in detecting our dataset, with low detection accuracy and a high miss rate. The average accuracy is reduced by 0.07%, and the precision is improved by 0.98%, as compared to the YOLOv5l model, which is sufficient to verify the effectiveness of the proposed model. The depth of the YOLOv5s model is 0.33 of the YOLOv5l, and the width of the YOLOv5s model is 0.5 of the YOLOv5l. With fewer convolutional layers and parameters, the model performance is closer and the detection speed is faster. It is shown in Table 4, Figure 8 and Figure 9.

Table 4.

The performance comparison of different models. The results of TAM-YOLO are shown in bold, and the best results are underlined.

Figure 8.

The time comparison of different models.

Figure 9.

The performance comparison of different models: (a) global, (b) local.

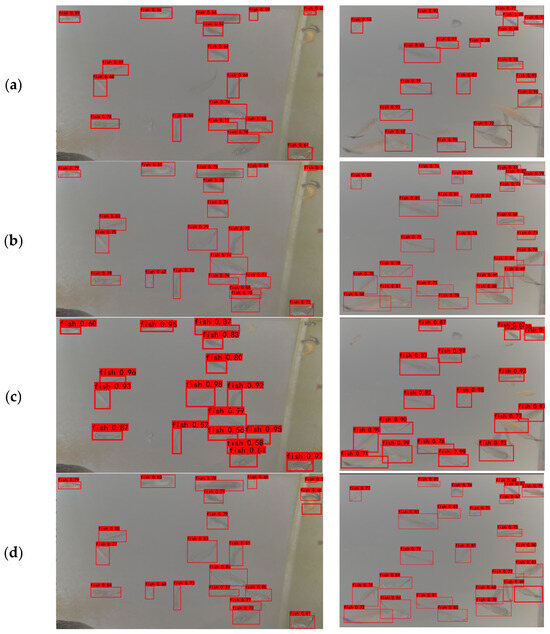

The results of the fish images detected by YOLOv4, YOLOv5s, SSD, and the model in this paper are shown in Figure 10. The fish detected by the model in this paper are more accurate and have a lower missed detection rate.

Figure 10.

The experimental results: (a) YOLOv4, (b) YOLOv5s, (c) SSD, (d) TAM-YOLO (ours).

6. Conclusions

We proposed the TAM-YOLO method with a triple attention mechanism for fish school detection. Positive sample matching was transferred to the data encapsulation process, and the EMA was added during the model training, which reduces pretraining time and improves detection accuracy. The CA and spatiotemporal attention mechanisms were integrated into the YOLOv5s backbone, which strengthens the feature extraction of channels and spatial positions. The more effective features were aggregated, and the model performance was optimized. Compared with the original model, mAP, precision, and recall increased by 2.34%, 2.06%, and 3.29%, respectively. In future work, it will be necessary to collect more fish images and compress the model to ensure its accuracy and real-time performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.L.; methodology, W.L. and Y.W.; software, Y.W. and J.Z.; validation, W.L. and Y.W.; formal analysis, L.H. and Y.W.; investigation, W.L. and Y.W.; resources, W.L. and J.Z.; data curation, Y.W. and L.H.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.W.; writing—review and editing, W.L., L.X. and C.Z.; visualization, Y.W.; supervision, L.X. and L.J.; project administration, L.J. and L.X.; funding acquisition, W.L. and L.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 61775139, in part by the Zhejiang Provincial Key R&D Program under Grant 2020C02020, in part by the Huzhou Key R&D Program Agricultural “Double Strong” Special Project (No. 2022ZD2060), and in part by the Huzhou Key Laboratory of Waters Robotics Technology (2022-3), Huzhou Science and Technology Bureau.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The experiments in this article do not involve biological experiments. The experimental materials used in the paper are all from the recording of aquaculture by cameras, and computer vision technology is used for some possible analysis.

Data Availability Statement

We will release all sources after the research is fully completed.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the support provided by Research Institute of Digital Intelligent Agriculture on site, as well as the data provided by Huzhou Fengshengwan Aquatic Products Co., Ltd.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Honarmand Ebrahimi, S.; Ossewaarde, M.; Need, A. Smart fishery: A systematic review and research agenda for sustainable fisheries in the age of AI. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6037–6057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Føre, M.; Frank, K.; Norton, T.; Svendsen, E.; Alfredsen, J.A.; Dempster, T.; Eguiraun, H.; Watson, W.; Stahl, A.; Sunde, L.M. Precision fish farming: A new framework to improve production in aquaculture. Biosyst. Eng. 2018, 173, 176–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, Z.; Wang, T.; Xu, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, D. Intelligent fish farm—The future of aquaculture. Aquac. Int. 2021, 29, 2681–2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, S.; Liu, J.; Gao, Q.; Dong, S.; Zhou, C. Deep learning for smart fish farming: Applications, opportunities and challenges. Rev. Aquac. 2021, 13, 66–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, D.; Merrifield, M.; Miller, K.M.; Lomonico, S.; Wilson, J.R.; Gleason, M.G. Opportunities to improve fisheries management through innovative technology and advanced data systems. Fish Fish. 2019, 20, 564–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkozhayeva, D.; Cisar, P. Image-Based Automatic Individual Identification of Fish without Obvious Patterns on the Body (Scale Pattern). Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5401–5417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Li, X.; Wang, Q.; Hao, Y. Advanced Techniques for the Intelligent Diagnosis of Fish Diseases: A Review. Animals 2022, 12, 2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulutas, G.; Ustubioglu, B. Underwater image enhancement using contrast limited adaptive histogram equalization and layered difference representation. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 15067–15091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawi, U.A. Fish classification using extraction of appropriate feature set. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. (IJECE) 2022, 12, 2488–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, J.; Xu, L. An automated fish counting algorithm in aquaculture based on image processing. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Forum on Mechanical, Control and Automation (IFMCA 2016), Shenzhen, China, 30–31 December 2016; pp. 358–366. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Zhu, J.; Li, D.; Zhao, R. Application of machine learning in intelligent fish aquaculture: A review. Aquaculture 2021, 540, 736724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsmadi, M.K.; Almarashdeh, I. A survey on fish classification techniques. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2020, 34, 1625–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Liu, M.Y.; Tuzel, O.; Xiao, J. R-CNN for Small Object Detection. In Proceedings of the Asian Conference on Computer Vision, Taipei, Taiwan, 20–24 November 2016; pp. 214–230. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, T.; Shen, Z.; Zou, H.; Zhong, P.; Chen, Y. Unsupervised adversarial domain adaptation based on interpolation image for fish detection in aquaculture. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 198, 107004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, M.; Goel, N. FishResNet: Automatic Fish Classification Approach in Underwater Scenario. SN Comput. Sci. 2021, 2, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Sun, X.; Liu, J.; Yang, X.; Zhou, C. Composited FishNet: Fish detection and species recognition from low-quality underwater videos. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2021, 30, 4719–4734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 26 June–1 July 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.; Hou, M.; Liang, Y.; He, T. An adaptive dead fish detection approach using SSD-MobileNet. In Proceedings of the 2020 Chinese Automation Congress (CAC), Shanghai, China, 6–8 November 2020; pp. 1973–1979. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, S.; Lu, J.; Wang, H.; Feng, Y.; Shi, C.; Li, D.; Zhao, R. A lightweight dead fish detection method based on deformable convolution and YOLOV4. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 198, 107098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, G.; Yang, X.; Wen, L.; Zhao, W. Diseased Fish Detection in the Underwater Environment Using an Improved YOLOV5 Network for Intensive Aquaculture. Fishes 2023, 8, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, S.; Wang, Q.; Li, D.; Zhao, R. Real-time detection and tracking of fish abnormal behavior based on improved YOLOV5 and SiamRPN++. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 192, 106512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, C.; Lu, X.; Wu, B. CME-YOLOv5: An Efficient Object Detection Network for Densely Spaced Fish and Small Targets. Water 2022, 14, 2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yu, H.; Gao, H.; Zhang, P.; Wei, S.; Xu, J.; Cheng, S.; Wu, J. Robust detection of farmed fish by fusing YOLOv5 with DCM and ATM. Aquac. Eng. 2022, 99, 102301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Yu, H.; Li, H.; Cheng, S.; Gu, L.; Zhang, P. Detection of fish stocks by fused with SKNet and YOLOv5 deep learning. J. Dalian Ocean. Univ. 2022, 37, 312–319. [Google Scholar]

- Han, F.; Zhu, J.; Liu, B.; Zhang, B.; Xie, F. Fish shoals behavior detection based on convolutional neural network and spatiotemporal information. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 126907–126926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaba, S.Y.; Nabi, M.; Shah, C.; Prior, J.; Campbell, M.D.; Wallace, F.; Ball, J.E.; Moorhead, R. Class-aware fish species recognition using deep learning for an imbalanced dataset. Sensors 2022, 22, 8268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Liu, Y.; Yu, H.; Fang, X.; Song, L.; Li, D.; Chen, Y. Computer vision models in intelligent aquaculture with emphasis on fish detection and behavior analysis: A review. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2021, 28, 2785–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-H.; Solanki, V.S.; Baraiya, H.J.; Mitra, A.; Shah, H.; Roy, S. A smart, sensible agriculture system using the exponential moving average model. Symmetry 2020, 12, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Q.; Zhou, D.; Feng, J. Coordinate attention for efficient mobile network design. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 13713–13722. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kweon, I.S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Du, Z.; Jiang, G.; Cui, M.; Li, D.; Liu, C.; Li, W. A Real-Time Individual Identification Method for Swimming Fish Based on Improved Yolov5. Available at SSRN 4044575. 2022; 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, G.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X. Tracking Multiple Zebrafish Larvae Using YOLOv5 and DeepSORT. In Proceedings of the 2022 8th International Conference on Automation, Robotics and Applications (ICARA), Prague, Czech Republic, 18–20 February 2022; pp. 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shao, Z.; Hoffmann, N. Global Attention Mechanism: Retain Information to Enhance Channel-Spatial Interactions. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.05561. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Shao, Z.; Teng, Y.; Hoffmann, N. NAM: Normalization-based Attention Module. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.12419. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).