IMTA Production of Pacific White Shrimp Integrated with Mullet, Sea Cucumber, Oyster, and Salicornia in a Biofloc System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site and Ethics

2.2. Experimental Organisms

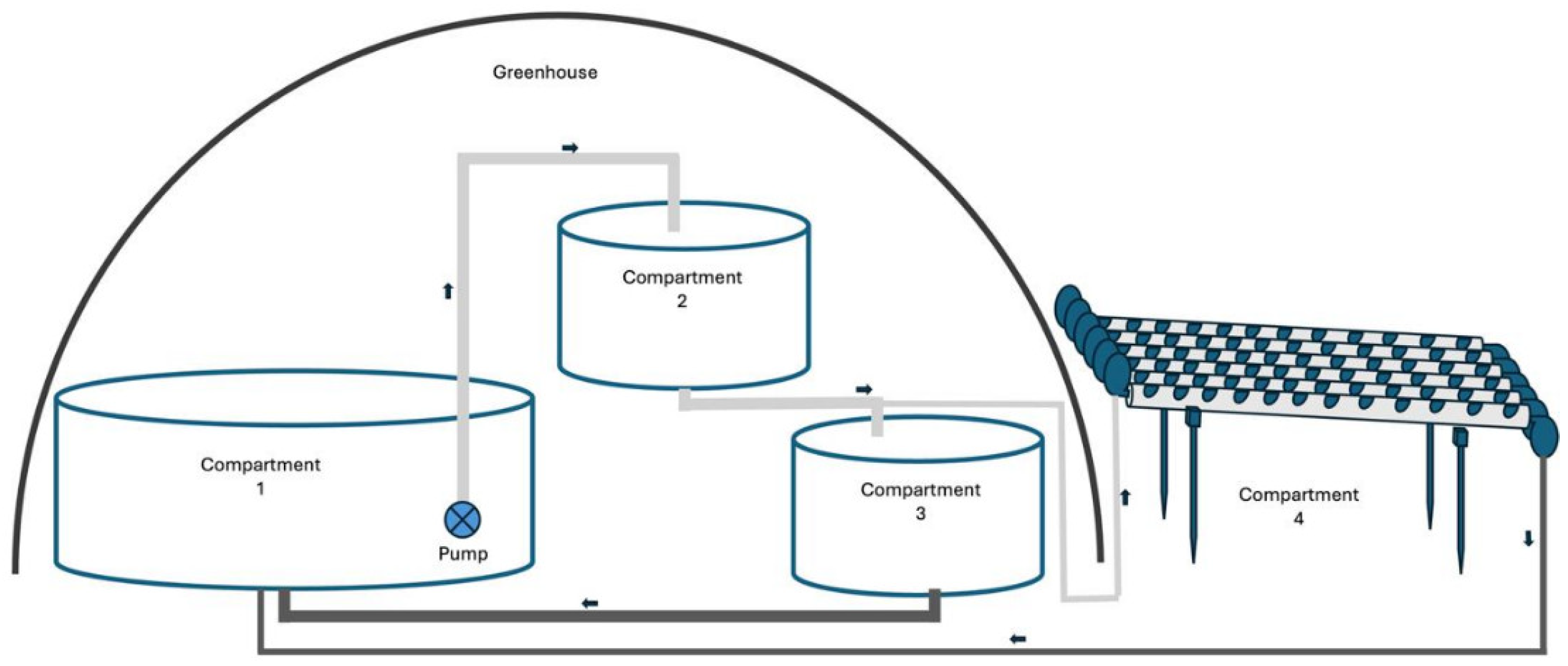

2.3. Experimental Design

2.4. Water Quality and Meteorological Parameters

2.5. Growth Performance and Feeding Protocol

2.6. Microbiological Analysis

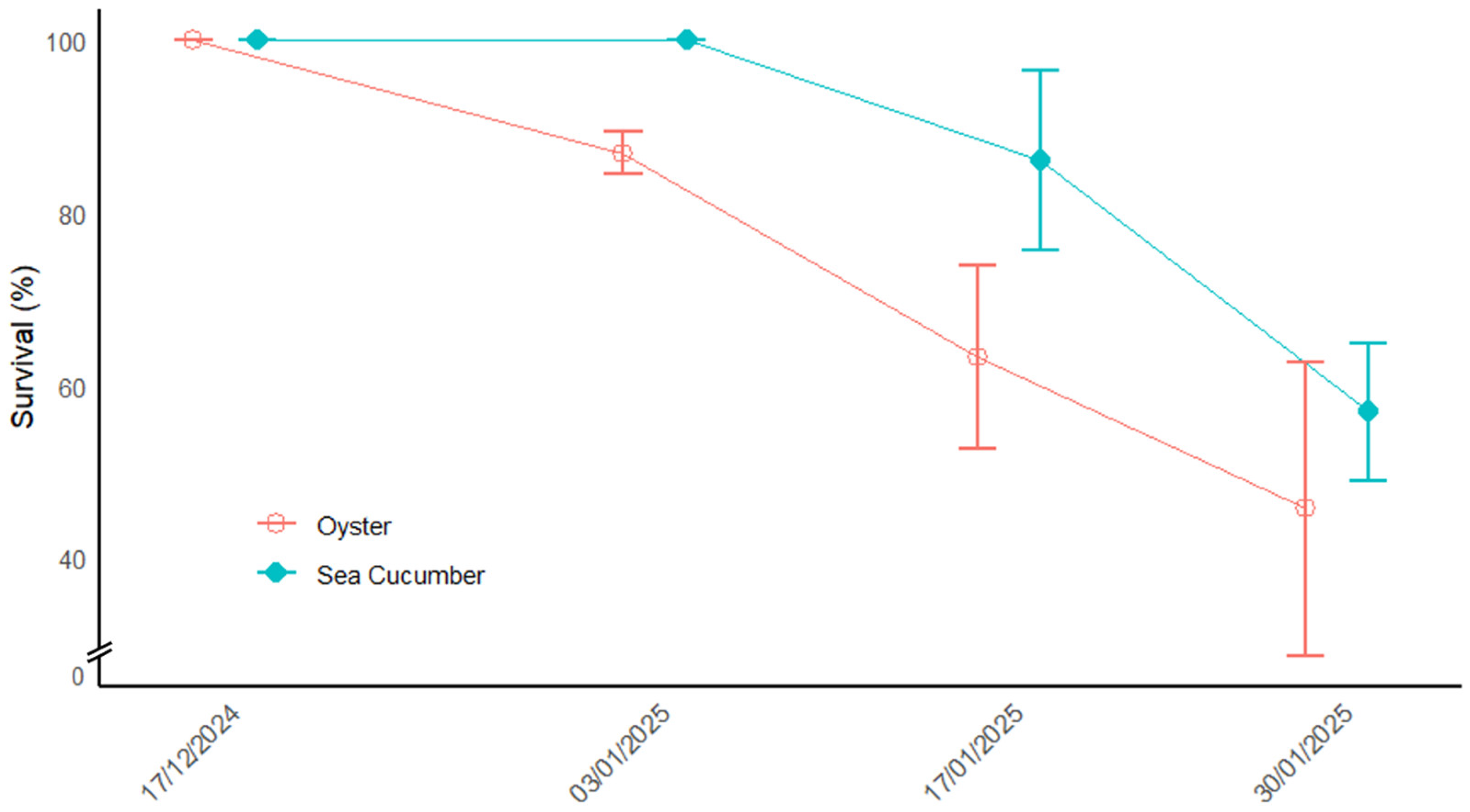

2.7. Survival Estimation and Correlation Analyses

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

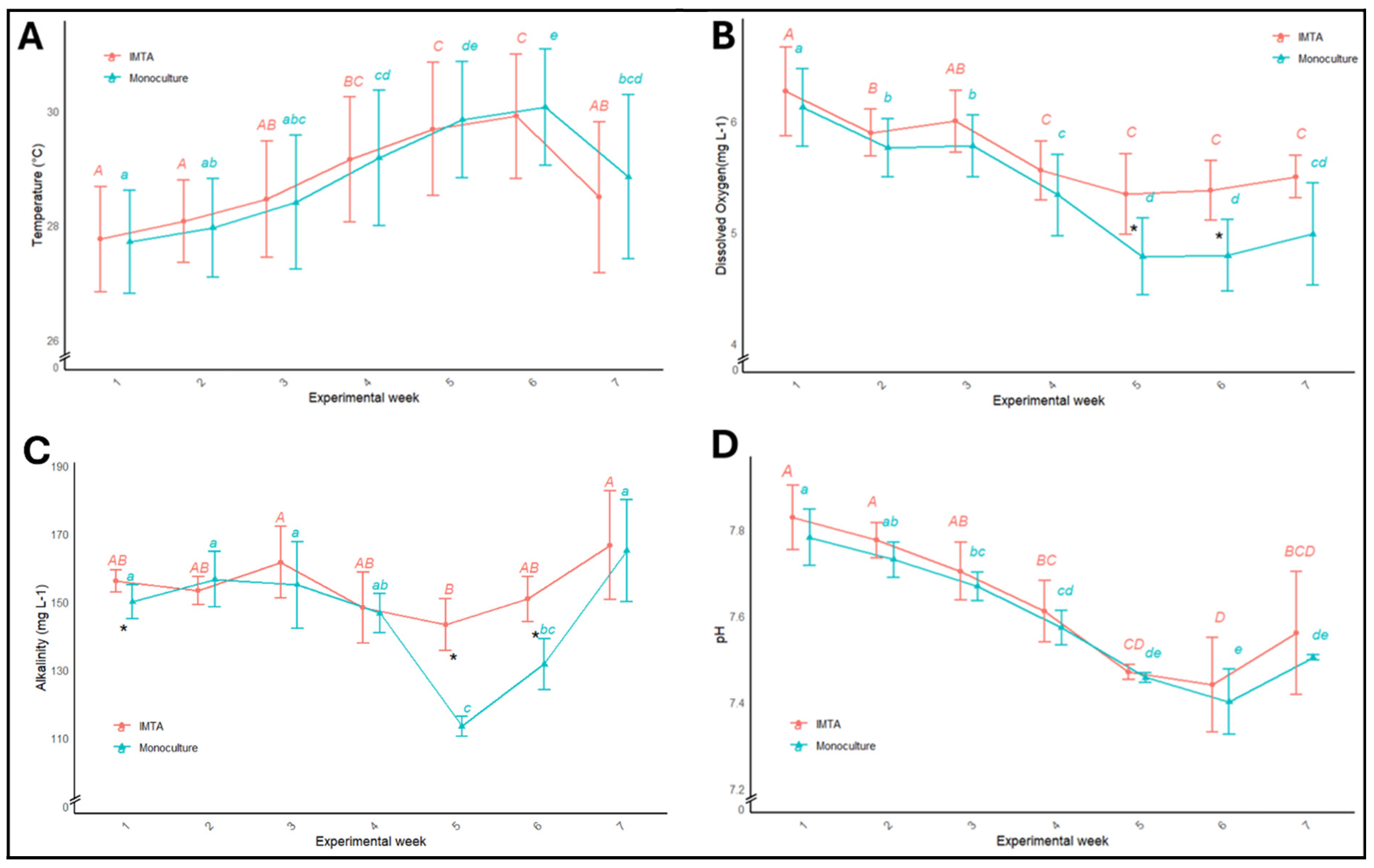

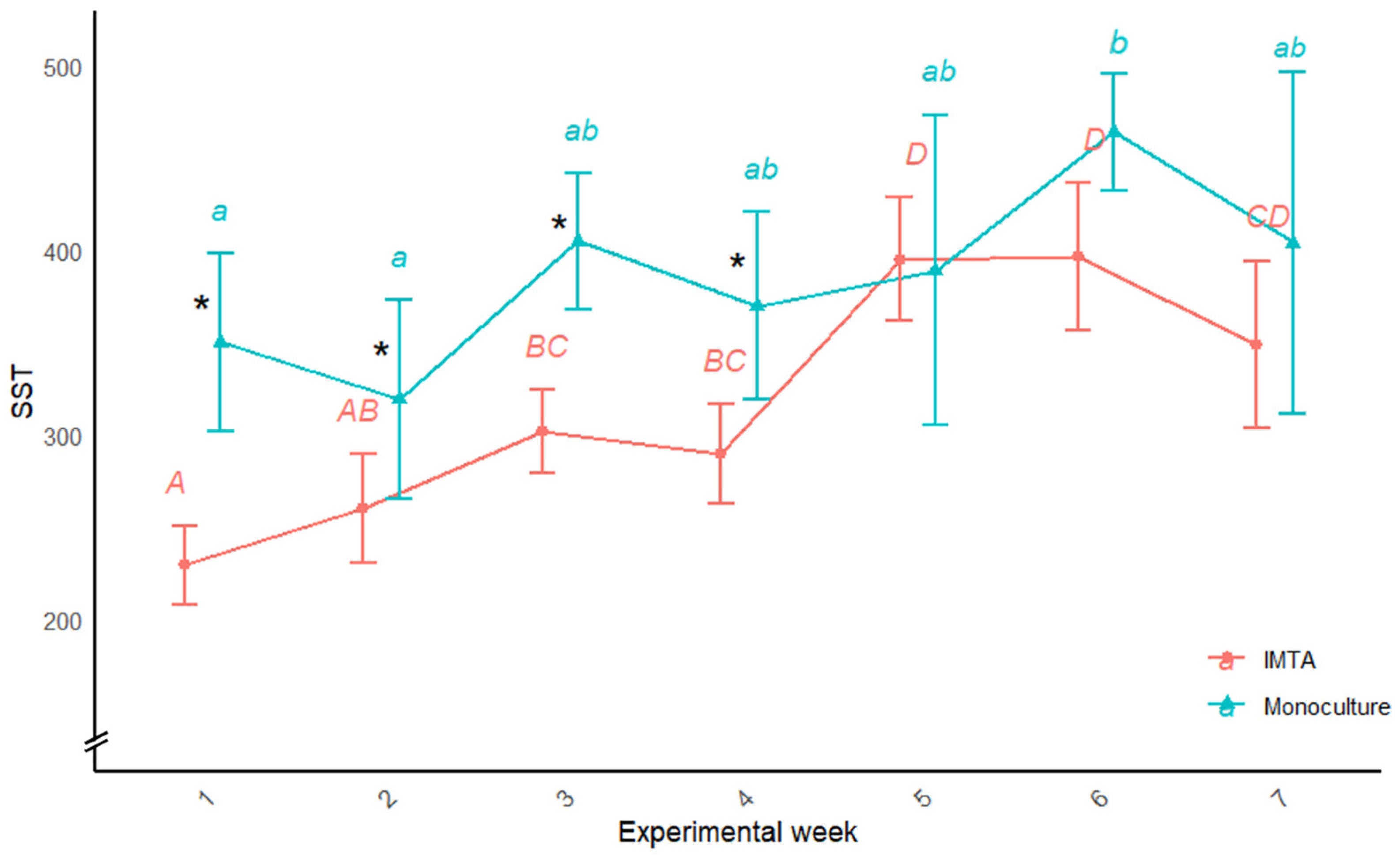

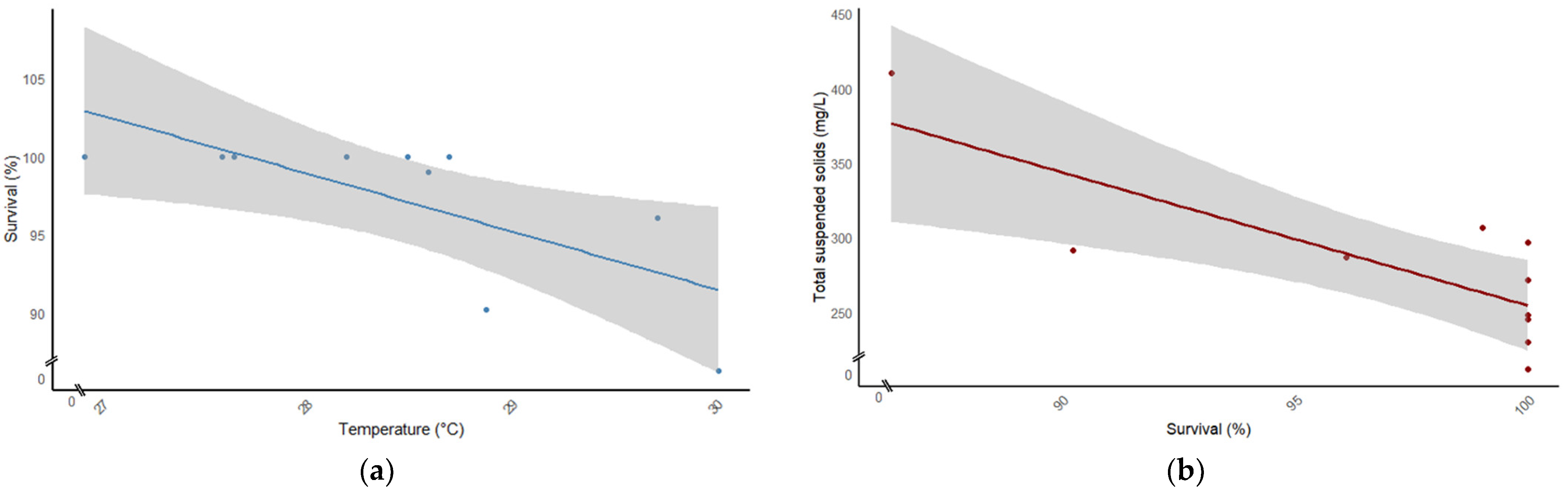

3.1. Water Quality Parameters

3.2. Growth Performance Parameters

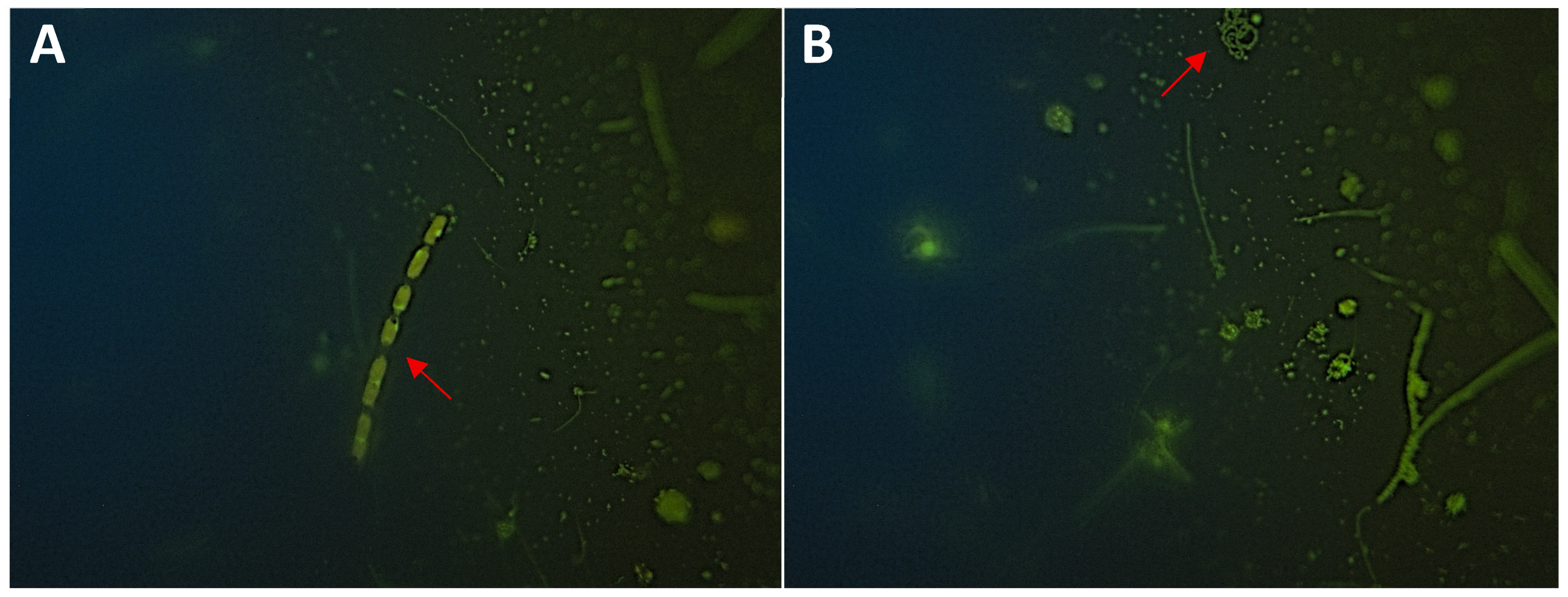

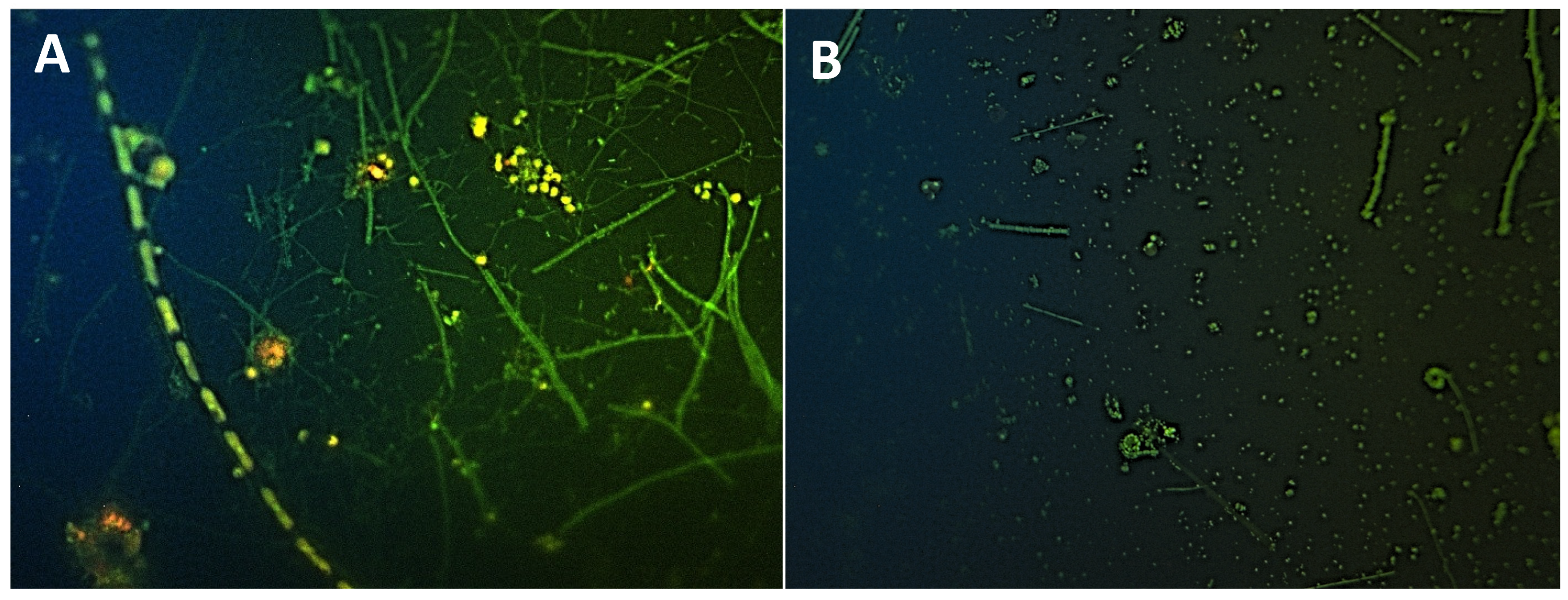

3.3. Microorganism Analysis

3.4. Correlations

4. Discussion

4.1. Growth Performance

4.2. Control of TSS

4.3. Water Quality

4.4. Microbial Community

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Avnimelech, Y. Carbon/nitrogen ratio as a control element in aquaculture systems. Aquaculture 1999, 176, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, E.L.C.; Abreu, P.C.; Cavalli, R.O.; Emerenciano, M.; De Abreu, L.; Wasielesky, W., Jr. Effect of practical diets with different protein levels on the performance of Farfantepenaeus paulensis juveniles nursed in a zero exchange suspended microbial flocs intensive system. Aquac. Nutr. 2010, 16, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avnimelech, Y. Biofloc Technology. In A Practical Guide Book; The World Aquaculture Society: Baton Rouge, LA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dauda, A.B. Biofloc technology: A review on the microbial interactions, operational parameters and implications to disease and health management of cultured aquatic animals. Rev. Aquac. 2020, 12, 1193–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schveitzer, R.; Baccarat, R.F.C.; Gaona, C.A.P.; Wasielesky, W., Jr.; Arantes, R. Concentration of suspended solids in superintensive culture of the Pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei with biofloc technology (BFT): A review. Rev. Aquac. 2024, 16, 785–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soaudy, M.R.; Ghonimy, A.; Greco, L.S.L.; Chen, Z.; Dyzenchauz, A.; Li, J. Total suspended solids and their impact in a biofloc system: Current and potentially new management strategies. Aquaculture 2023, 572, 739524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poli, M.A.; Legarda, E.C.; Lorenzo, M.A.; Pinheiro, I.; Martins, M.A.; Seiffert, W.Q.; Vieira, F. Integrated multitrophic aquaculture applied to shrimp rearing in a biofloc system. Aquaculture 2019, 511, 734274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, J.; Singh, S.K.; Pawar, L.; Biswas, P.; Meitei, M.M.; Meena, D.K. Chapter 15—Integrated multi-trophic aquaculture: A balanced ecosystem approach to blue revolution. In Organic Farming, 2nd ed.; Sarathchandran, Unni, M.R., Thomas, S., Meena, D.K., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2023; pp. 513–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubillo, A.M.; Ferreira, J.G.; Robinson, S.M.C.; Pearce, C.M.; Corner, R.A.; Johansen, J. Role of deposit feeders in integrated multi-trophic aquaculture—A model analysis. Aquaculture 2016, 453, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, P.C.M.; Silva, A.E.M.; Silva, D.A.; Silva, S.M.B.C.; Brito, L.O.; Gálvez, A.O. Effect of stocking density of Crassostrea sp. In a multitrophic biofloc system with Litopenaeus vannamei in nursery. Aquaculture 2021, 530, 735913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holanda, M.; Santana, G.; Furtado, P.; Rodrigues, R.V.; Cerqueira, V.R.; Sampaio, L.A.; Wasielesky, W.; Poersch, L.H. Evidence of total suspended solids control by Mugil liza reared in an integrated system with pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei using biofloc technology. Aquac. Rep. 2020, 18, 100479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnull, J.; Wilson, A.; Brayne, K.; Dexter, K.; Donah, A.; Gough, C.; Klückow, T.; Ngwenya, B.; Tudhope, A. Ecological co-benefits from sea cucumber farming: Holothuria scabra increases growth rate of seagrass. Aquac. Environ. Interact. 2021, 13, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, S.W.; Conand, C.; Byrne, S.U.M. Ecological Roles of Exploited Sea Cucumbers. In Oceanography and Marine Biology: An Annual Review; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras-Sillero, M.E.; Pacheco-Vega, J.M.; Valdez-González, F.J.; De La Paz-Rodríguez, G.; Cadena-Roa, M.A.; Bautista-Covarrubias, J.C.; Godínez-Siordia, D.E. Polyculture of White shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) and sea cucumber (Holothuria inornata) in a biofloc system. Aquac. Res. 2020, 51, 4410–4420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chang, Y. Sea Cucumber Aquaculture in China. In Echinoderm Aquaculture; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meñez, M.A.; Tech, E.; Ticao, I.; Gorospe, J.R.; Edullantes, C.; Rioja, R.A. Adaptive and integrated culture production systems for the tropical sea cucumber Holothuria scabra. Fish. Res. 2016, 186, 502–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, B.A.A.; Rocha, J.L.; Pinto, P.H.O.; Zacheu, T.; Chede, A.C.; Magnotti, C.C.F.; Cerqueira, V.R.; Arana, L.A.V. Integrated culture of white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei and mullet Mugil liza on biofloc technology: Zootechnical performance, sludge generation, and Vibrio spp. reduction. Aquaculture 2020, 524, 735234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, L.C.d.O.; Poersch, L.H.d.S.; Abreu, P.C. Biofloc removal by the oyster Crassostrea gasar as a candidate species to an Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture (IMTA) system with the marine shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. Aquaculture 2021, 540, 736731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doncato, K.B.; Costa, C.S. Effects of cutting on vegetative development and biomass quality of perennial halophytes grown in saline aquaponics. Hortic. Bras. 2022, 40, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, M.R.; Araneda, J.; Osses, A.; Orellana, J.; Gallardo, J.A. Efficiency of Salicornia neei to Treat Aquaculture Effluent from a Hypersaline and Artificial Wetland. Agriculture 2020, 10, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harboub, N.; Mighri, H.; Bennour, N.; Dbara, M.; Pereira, C.; Chouikhi, N.; Custódio, L.; Abdellaoui, R.; Akrout, A. Nutritional profile, chemical composition and health promoting properties of Salicornia emerici Duval-Jouve and Sarcocornia alpini (Lag.) Rivas Mart. From southern Tunisia. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2025, 64, 103502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jory, D.E.; Cabrera, T.R.; Dugger, D.; Fegan, D.; Lee, P.G.; Lawrence, A.L.; Jackson, C.J.; McIntosh, R.P.; Castañeda, J. A global review of shrimp feed management: Status and perspectives. New Wave Proc. Spec. Sess. Sustain. Shrimp Cult. Aquac. 2001, 2001, 104–152. [Google Scholar]

- Strickland, J.D.H.; Parsons, T.R. A Practical Handbook of Seawater Analysis, 2nd ed.; Fisheries Research Board of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1972; Available online: https://epic.awi.de/id/eprint/39262/1/Strickland-Parsons_1972.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- APHA. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 24th ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA; American Water Works Association: Denver, CO, USA; Water Environment Federation: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission Chemical methods for use in marine environment monitoring. In Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission Manuals and Guides; 12; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1983; p. 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminot, A.; Centre National pour l’Exploitation des Oceans; Chaussepied, M. Manuel des Analyses Chimiques En Milieu Marin; CNEXO: Brest, France, 1983; Available online: https://agris.fao.org/search/en/providers/122621/records/647396bae01106880097f33c (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- García-Robledo, E.; Corzo, A.; Papaspyrou, S. A fast and direct spectrophotometric method for the sequential determination of nitrate and nitrite at low concentrations in small volumes. Mar. Chem. 2014, 162, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglene, S.C.; Seymour, J.E.; Ramofafia, C. Survival and growth of cultured juvenile sea cucumbers, Holothuria scabra. Aquaculture 1999, 178, 293–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Dong, S. Growth and oxygen consumption of the juvenile sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus (Selenka) at constant and fluctuating water temperatures. Aquac. Res. 2006, 37, 1327–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbie, J.E.; Daley, R.J.; Jasper, S. Use of nuclepore filters for counting bacteria by fluorescence microscopy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1977, 33, 1225–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoang, M.N.; Nguyen, P.N.; Le, D.V.B.; Nguyen, D.V.; Bossier, P. Effects of stocking density of gray mullet Mugil cephalus on water quality, growth performance, nutrient conversion rate, and microbial community structure in the white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei integrated system. Aquaculture 2018, 496, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, M.N.; Nguyen, P.N.; Bossier, P. Water quality, animal performance, nutrient budgets and microbial community in the biofloc-based polyculture system of white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei and gray mullet, Mugil cephalus. Aquaculture 2020, 515, 734610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, L.C.d.O.; Carvalho, A.; Holanda, M.; Santos, J.; Borges, L.; Guterres, B.; Nam Junior, J.; Fonseca, V.; Muller, L.; Romano, L.; et al. Biological responses of oyster Crassostrea gasar exposed to different concentrations of biofloc. Fishes 2023, 8, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Shi, C.; Yang, B.; Li, Q.; Liu, S. High temperature aggravates mortalities of the Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) infected with Vibrio: A perspective from homeostasis of digestive microbiota and immune response. Aquaculture 2023, 568, 739309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybovich, M.; Peyre, M.K.L.; Hall, S.G.; Peyre, J.F.L. Increased temperatures combined with lowered salinities differentially impact oyster size class growth and mortality. J. Shellfish Res. 2016, 35, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora, L.N.; Jeffs, A.G. Feeding, metabolism and growth in response to temperature in juveniles of the Australasian sea cucumber, Australostichopus mollis. Aquaculture 2012, 358–359, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Chen, Y.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, S.; Ru, X.; Xing, L.; Zhang, T.; Yang, H.; Li, J. Effect of temperature on growth, energy budget, and physiological performance of green, white, and purple color morphs of sea cucumber, Apostichopus japonicus. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2018, 49, 625–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madruga, A.S.; Félix, P.M.; Sousa, J.; Azevedo e Silva, F.; Brito, A.C.; Mendes, S.; Pombo, A. Effect of rearing temperature in the growth of hatchery reared juveniles of the sea cucumber Holothuria arguinensis (Koehler & Vaney, 1906). Aquaculture 2023, 562, 738809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wei, C.; Chang, Y.; Ding, J. Response of bacterial community in sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus intestine, surrounding water and sediment subjected to high-temperature stress. Aquaculture 2021, 535, 736353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M.d.S.; Carvalho, A.; Santos, J.; Holanda, M.; Poersch, L.H.; Costa, C.S.B. Biofloc formation strategy effects on halophyte integration in IMTA with marine shrimp and tilapia. Aquac. J. 2024, 4, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doncato, K.B.; Costa, C.S.B. Evaluation of nitrogen and phosphorus nutritional needs of halophytes for saline aquaponics. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2023, 64, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legarda, E.C.; Martins, M.A.; Pereira, P.K.M.; Carneiro, R.F.S.; Pinheiro, I.C.; Seiffert, W.Q.; Machado, C.; Lorenzo, M.A.; Vieira, F.N. Shrimp rearing in biofloc integrated with different mullet stocking densities. Aquac. Res. 2020, 51, 3571–3581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, K.; Vidal-Ramirez, F.; Dove, S.; Deaker, D.; Byrne, M. Altered sediment biota and lagoon habitat carbonate dynamics due to sea cucumber bioturbation in a high-pCO2 environment. Glob. Change Biol. 2018, 24, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collard, M.; Laitat, K.; Moulin, L.; Catarino, A.I.; Grosjean, P.; Dubois, P. Buffer capacity of the coelomic fluid in echinoderms. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2013, 166, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosso, L.; Rampacci, M.; Pensa, D.; Fianchini, A.; Batır, E.; Aydın, İ.; Ciriminna, L.; Felix, P.M.; Pombo, A.; Lovatelli, A.; et al. Evaluating sea cucumbers as extractive species for benthic bioremediation in mussel farms. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Y.; Stuart, K.; Rotman, F.; Ernst, D.; Drawbridge, M. The culture of fish, mussels, sea cucumbers and macroalgae in a modular integrated multi-tropic recirculating aquaculture system (IMTRAS): Performance and waste removal efficiencies. Aquaculture 2024, 585, 740720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyango, G.W.; Bhowmick, G.D.; Sahoo Bhattacharya, N. A critical review of irrigation water quality index and water quality management practices in micro-irrigation for efficient policy making. Desalination Water Treat. 2024, 318, 100304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, A.J.; Seaborn, G.; Leffler, J.W.; Wilde, S.B.; Lawson, A.; Browdy, C.L. Characterization of microbial communities in minimal-exchange, intensive aquaculture systems and the effects of suspended solids management. Aquaculture 2010, 310, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schveitzer, R.; Arantes, R.; Costódio, P.F.S.; do Espírito Santo, C.M.; Arana, L.V.; Seiffert, W.Q.; Andreatta, E.R. Effect of different biofloc levels on microbial activity, water quality and performance of Litopenaeus vannamei in a tank system operated with no water exchange. Aquac. Eng. 2013, 56, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, H.; Wei, H.; Zhu, X.; Han, D.; Jin, J.; Yang, Y.; Xie, S. Biofloc formation improves water quality and fish yield in a freshwater pond aquaculture system. Aquaculture 2019, 506, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, W.; Krysiak-Baltyn, K.; Scales, P.J.; Martin, G.J.O.; Stickland, A.D.; Gras, S.L. The influence of protruding filamentous bacteria on floc stability and solid-liquid separation in the activated sludge process. Water Res. 2017, 123, 578–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.-X.; Wang, J.; Liu, S.-Y.; Guo, J.-S.; Fang, F.; Chen, Y.-P.; Yan, P. New insight into filamentous sludge bulking: Potential role of AHL-mediated quorum sensing in deteriorating sludge floc stability and structure. Water Res. 2022, 212, 118096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezbrytska, I.; Bilous, O.; Sereda, T.; Ivanova, N.; Pohorielova, M.; Shevchenko, T.; Dubniak, S.; Lietytska, O.; Zhezherya, V.; Polishchuk, O.; et al. Effects of war-related human activities on microalgae and macrophytes in freshwater ecosystems: A case study of the Irpin river basin, Ukraine. Water 2024, 16, 3604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teles, E.a.P.; Xavier, J.F.; Arcênio, F.S.; Amaya, R.L.; Gonçalves, J.V.S.; Rouws, L.F.M.; Zonta, E.; Coelho, I.S. Characterization and evaluation of potential halotolerant phosphate solubilizing bacteria from Salicornia fruticosa rhizosphere. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 14, 1324056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Monoculture | IMTA |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature (°C) | 28.86 ± 1.11 | 28.81 ± 1.06 |

| DO (mg L−1) | 5.40 ± 0.55 a | 5.73 ± 0.41 b |

| Salinity (g L−1) | 31.24 ± 1.04 | 31.88 ± 0.85 |

| pH | 7.59 ± 0.16 | 7.64 ± 0.18 |

| Alkalinity (mg L−1) | 147.44 ± 14.48 | 155.38 ± 6.57 |

| Cal used (kg) | 4.29 ± 0.38 a | 2.13 ± 0.52 b |

| Total ammonia nitrogen (mg L−1) | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.06 ± 0.01 |

| Nitrite nitrogen (mg L−1) | 0.43 ± 0.19 | 0.40 ± 0.13 |

| Nitrate nitrogen (mg L−1) | 34.17 ± 31.65 | 25.33 ± 25.24 |

| Orthophosphate (mg L−1) | 3.69 ± 1.33 | 3.24 ± 1.26 |

| Parameter | Monoculture | IMTA |

|---|---|---|

| SS (mg L−1) | 11.78 ± 3.52 | 10.70 ± 3.93 |

| TSS (mg L−1) | 373.33 ± 53.48 a | 299.56 ± 68.45 b |

| Clarifier use (h) | 29.10 ± 2.22 a | 18.97 ± 4.02 b |

| Sludge produced (Kg) | 15.87 ± 2.61 a | 9.37 ± 1.49 b |

| Monoculture | IMTA | |

|---|---|---|

| Shrimp | ||

| Initial weight (g) | 2.71 ± 0.13 | 2.59 ± 0.05 |

| Final weight (g) | 10.12 ± 1.08 | 9.61 ± 0.35 |

| Daily growth (g day−1) | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 0.16 ± 0.01 |

| Feed offered (kg) | 66.91 ± 0.69 | 67.91 ± 0 |

| Feed conversion rate | 1.88 ± 0.05 | 1.78 ± 0.08 |

| Final biomass (kg) | 51.79 ± 1.28 | 53.72 ± 1.56 |

| Yield (kg m−3) | 3.24 ± 0.08 | 3.36 ± 0.10 |

| Survival (%) | 85.86 ± 8.08 | 93.33 ± 5.77 |

| Mullet | ||

| Initial weight (g) | 17.16 ± 0.6 | |

| Initial standard length (cm) | 11.51 ± 0.14 | |

| Initial total length (cm) | 9.97 ± 0.14 | |

| Final weight (g) | 30.14 ± 0.4 | |

| Final standard length (cm) | 11.76 ± 0.02 | |

| Final total length (cm) | 13.94 ± 0.04 | |

| Daily growth (g day−1) | 0.29 ± 0.02 | |

| Feed offered (kg) | 2.16 ± 0.01 | |

| Feed conversion rate | 1.53 ± 0.03 | |

| Final biomass (kg) | 3.47 ± 0.03 | |

| Yield (kg m−3) | 0.87 ± 0.01 | |

| Survival (%) | 95.83 ± 1.67 | |

| Oyster | ||

| Initial weight (g) | 33.34 ± 1.04 | |

| Initial height (cm) | 5.75 ± 0.13 | |

| Initial length (cm) | 4.71 ± 0.10 | |

| Initial width (cm) | 1.87 ± 0.13 | |

| Final weight (g) | 30.69 ± 0.96 | |

| Final height (cm) | 6.01 ± 0.23 | |

| Final length (cm) | 4.85 ± 0.08 | |

| Final width (cm) | 2.16 ± 0.05 | |

| Daily growth (g day−1) | −0.06 ± 0.02 | |

| Final biomass (kg) | 1.98 ± 0.80 | |

| Yield (kg m−3) | 0.66 ± 0.27 | |

| Survival (%) | 45.71 ± 17.01 | |

| Sea Cucumber | ||

| Initial weight (g) | 90.45 ± 2.04 | |

| Final weight (g) | 66.57 ± 4.93 | |

| Daily growth (g day−1) | −0.53 ± 0.12 | |

| Final biomass (kg) | 1.09 ± 0.23 | |

| Yield (kg m−3) | 0.36 ± 0.08 | |

| Survival (%) | 56.9 ± 7.90 | |

| Salicornia | ||

| Shoot biomass (g) | 15.20 ± 1.26 | |

| Root biomass (g) | 1.13 ± 0.21 | |

| Total biomass (g) | 16.33 ± 1.38 | |

| Shoot allocation (%) | 93.37 ± 0.74 | |

| Bench yield (kg m−2) | 0.43 ± 0.09 | |

| Survival (%) | 77.78 ± 17.67 |

| Relative Abundances (%) | Final | |

|---|---|---|

| Monoculture | IMTA | |

| Cocoides | 47.04 ± 2.35 a | 86.72 ± 1.49 b |

| Free filamentous bacteria | 34.22 ± 5.01 a | 4.24 ± 0.61 b |

| Adherent filamentous bacteria | 3.28 ± 0.63 a | 0.68 ± 0.27 b |

| Vibrio | 4.29 ± 0.76 | 2.38 ± 0.86 |

| Bacilo | 0.91 ± 0.33 a | 3.55 ± 0.84 b |

| Fusiform bacteria | 8.2 ± 1.32 a | 1.66 ± 0.18 b |

| Amoebas | 0 ± 0 | 0.1 ± 0.07 |

| Small cyanobacteria | 1.46 ± 0.18 a | 0.29 ± 0.16 b |

| Big cyanobacteria | 0.6 ± 0.17 a | 0.01 ± 0.01 b |

| Cyanobacteria cluster | 0 ± 0 | 0.36 ± 0.15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Estévez Hernández, E.A.; Santos, I.; Moraes, L.; Kashane, M.S.; Okamoto, M.H.; Sampaio, L.A.; Krummenauer, D.; Costa, C.S.B.; Rodrigues, R.V.; Martínez-Llorens, S.; et al. IMTA Production of Pacific White Shrimp Integrated with Mullet, Sea Cucumber, Oyster, and Salicornia in a Biofloc System. Fishes 2026, 11, 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11020098

Estévez Hernández EA, Santos I, Moraes L, Kashane MS, Okamoto MH, Sampaio LA, Krummenauer D, Costa CSB, Rodrigues RV, Martínez-Llorens S, et al. IMTA Production of Pacific White Shrimp Integrated with Mullet, Sea Cucumber, Oyster, and Salicornia in a Biofloc System. Fishes. 2026; 11(2):98. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11020098

Chicago/Turabian StyleEstévez Hernández, Enrique A., Ivanilson Santos, Laura Moraes, Morena Salala Kashane, Marcelo H. Okamoto, Luís André Sampaio, Dariano Krummenauer, César S. B. Costa, Ricardo V. Rodrigues, Silvia Martínez-Llorens, and et al. 2026. "IMTA Production of Pacific White Shrimp Integrated with Mullet, Sea Cucumber, Oyster, and Salicornia in a Biofloc System" Fishes 11, no. 2: 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11020098

APA StyleEstévez Hernández, E. A., Santos, I., Moraes, L., Kashane, M. S., Okamoto, M. H., Sampaio, L. A., Krummenauer, D., Costa, C. S. B., Rodrigues, R. V., Martínez-Llorens, S., & Poersch, L. H. (2026). IMTA Production of Pacific White Shrimp Integrated with Mullet, Sea Cucumber, Oyster, and Salicornia in a Biofloc System. Fishes, 11(2), 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11020098