Research on the Impact of Factor Mobility on the Economic Efficiency of Marine Fisheries in China’s Coastal Regions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Analysis

2.1. The Direct Impact of FM on the EEMF

2.2. The Indirect Impact of FM on the EEMF

2.3. The Impact of FM on the EEMF from a Heterogeneity Perspective

3. Methods and Data Sources

3.1. Model Construction

3.1.1. Reference Model

3.1.2. Tobit Model

3.1.3. Mediated Effect Model

3.2. Variable Selection and Explanation

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

3.2.2. Core Explanatory Variable

3.2.3. Mediating Variable

3.2.4. Control Variables

3.3. Data Source

4. Results

4.1. Features of Spatiotemporal Evolution

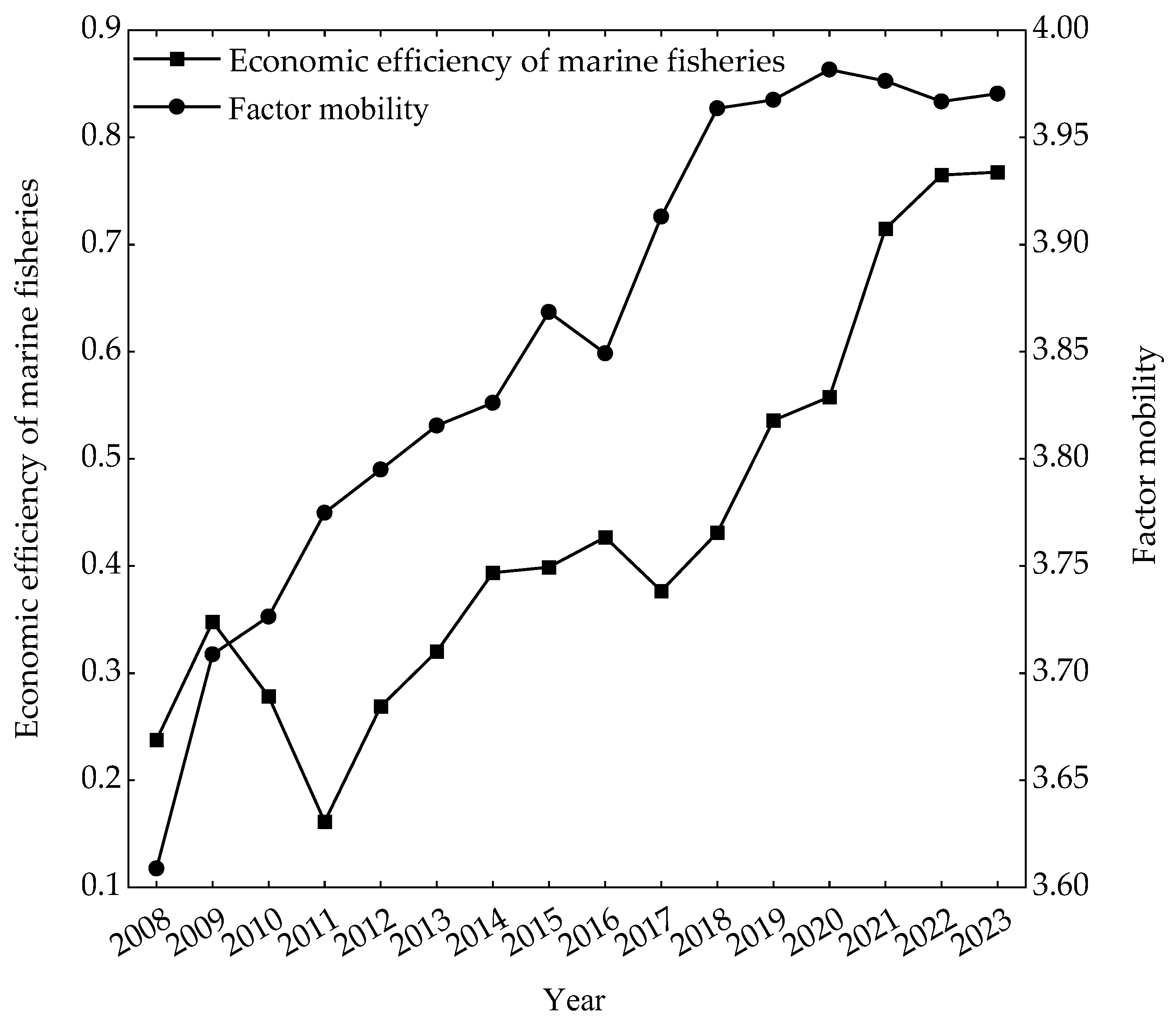

4.1.1. Temporal Evolutionary Trend

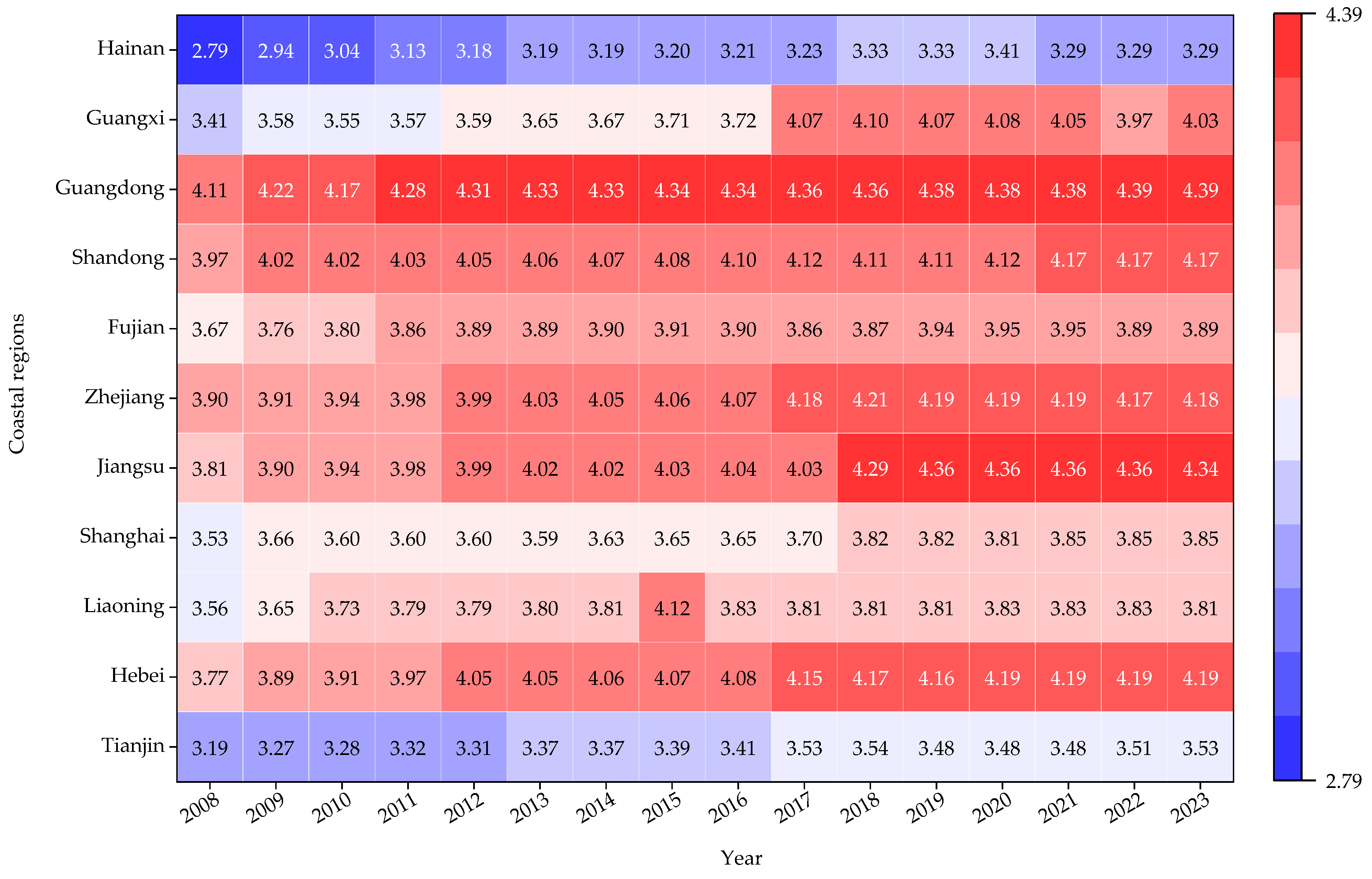

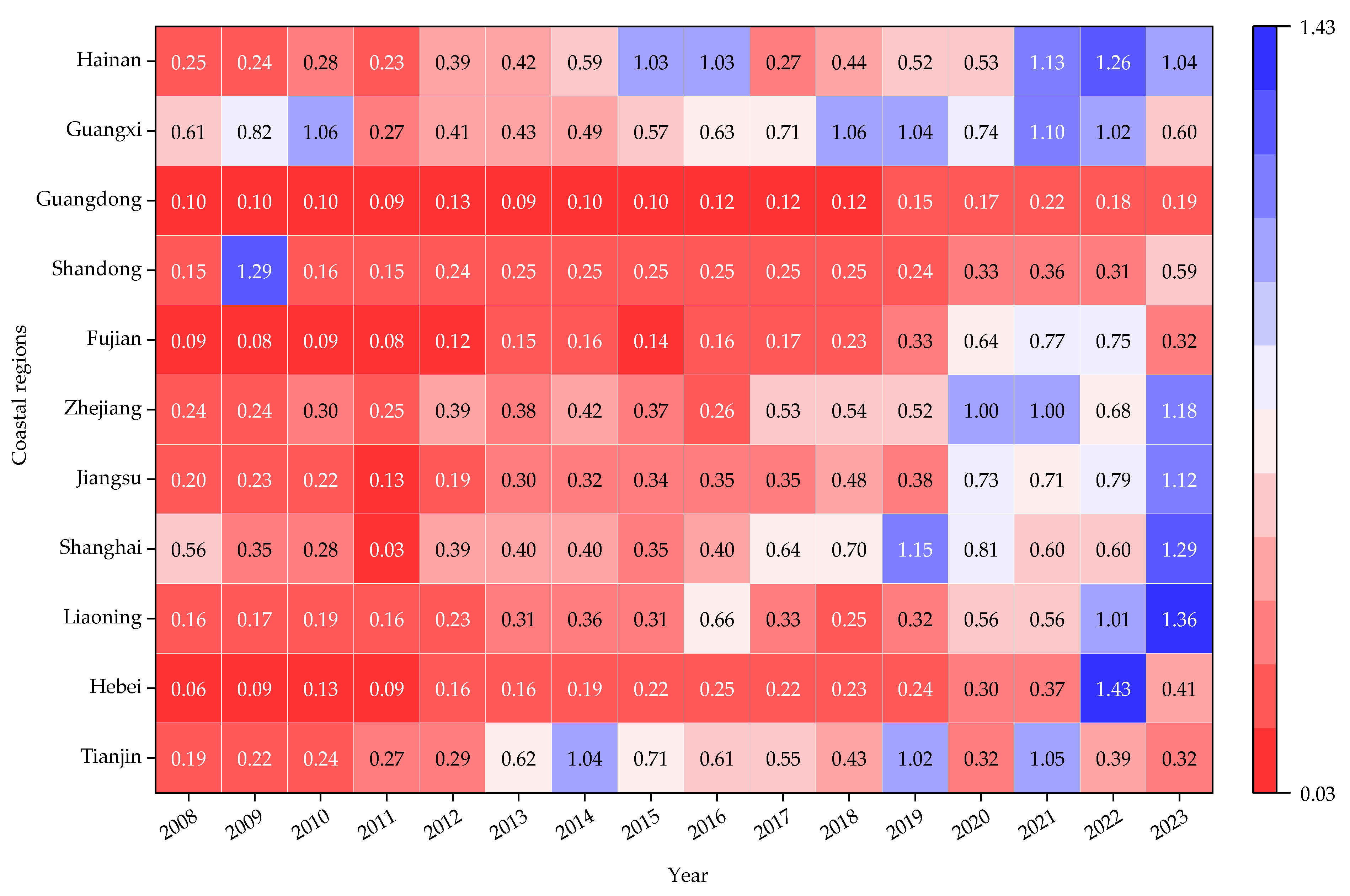

4.1.2. Spatial Distribution Characteristics

4.2. Direct Impact Analysis

4.3. Endogeneity and Robustness Tests

4.3.1. Endogeneity Test

4.3.2. Robustness Test

- (1)

- Shorten the time window

- (2)

- Increase control variables

4.4. Indirect Impact Analysis

4.5. Regional Heterogeneity Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Based on the development level of EEMF in coastal regions, focus on leveraging the leading advantages of high-value regions, overcoming development bottlenecks in medium-value regions, and synergistically driving the development of low-value regions, thereby enhancing the overall EEMF in coastal regions. Specifically, for coastal regions with high-value EEMF, focus on leveraging leading advantages, continuously strengthening investment in scientific research and development, deepening cross-sector integration between marine fisheries and industries such as finance and cultural tourism, striving to build high-value-added industrial chains, and promoting high-quality development of the marine fisheries economy. For provinces with moderate efficiency, the focus should be on overcoming funding, technology, and industrial structure bottlenecks. Policy support should be strengthened to advance the green transformation of marine fisheries. Concurrently, industrial layout should be optimized to cultivate distinctive marine fishery clusters, driving the sector toward modernization and greater efficiency. For low-value regions, it is imperative to accelerate the phasing out of traditional inefficient production capacity, break free from the constraints of single-model operations, actively introduce modern aquaculture technologies, develop new high-value-added marine fisheries industries, and strengthen regional coordination and resource sharing, while enhancing fisheries’ resilience against market fluctuations through ecological monitoring and early-warning risk systems.

- (2)

- Unimpede the channels for the FM in coastal regions and drive the development of EEMF through the coordinated efforts of multiple factors. Establish a cross-regional platform for the flow of marine fishery resources in coastal regions to facilitate the free and efficient movement of capital, technology, labor, data, and other resources. This initiative aims to reduce resource mobility costs and unlock synergistic effects among these elements. Promote the transition of densely populated coastal regions from quantitative concentration to qualitative optimization, guide the workforce toward high-value-added marine fisheries sectors, and optimize the population and talent structure. Fully leverage the significant role of human capital in driving progress by enhancing the knowledge, skills, and innovation capabilities of coastal marine fishery workers through specialized training programs and the recruitment of high-caliber talent. Increase investment in information infrastructure in coastal regions, develop information technologies suitable for marine fishery production, circulation and other links, and promote digital transformation. Strengthen fiscal support, optimize the allocation of public funds, and solidify the foundation for the sustainable development of the marine fisheries economy. In response to the impacts of opening up to the outside world, coastal regions must actively address external competition, accelerate the optimization and upgrading of the marine fisheries industry structure, improve policy support systems, enhance resource allocation efficiency, and fully unlock the potential benefits of opening up.

- (3)

- Further leverage technological innovation and industrial upgrading to enhance the EEMF. On the one hand, increase investment in scientific and technological innovation in the marine fishery sector, improve the collaborative mechanism for scientific and technological innovation and technology transfer, accelerate the cultivation of talent, and further enhance the intermediary role of scientific and technological innovation in marine fishery. On the other hand, continuously promote the upgrading of the marine fishery industrial structure, formulate policies guiding the advancement of the industrial structure, optimize the spatial layout of the marine fishery industry, and drive marine fishery resources to flow into high-value-added fields. Finally, improve the policy coordination mechanism, strengthen the linkage between policies on FM, scientific and technological innovation, and industrial upgrading, smooth the path for FM, and thereby achieve a comprehensive improvement in the EEMF.

- (4)

- Promote coordinated regional development in coastal regions and reduce regional heterogeneity in the impact of FM on the EEMF. Focusing on the industrial structure and infrastructure gaps within the Southern Marine Economic Circle, we will increase investment in marine fishery infrastructure, cultivate diversified sectors such as marine ranching and recreational fishing, and stimulate the driving force of MF. Leveraging the port trade advantages of the Northern Marine Economic Circle, we will integrate superior marine fishery resources, deepen the integration between port operations and marine fishery industries, strengthen corporate technological cooperation and innovation, and further unleash synergistic effects among key factors. Consolidate the advantages of the Eastern Marine Economic Circle in gathering key resources, continuously attract further resource concentration, and establish a hub for marine fisheries science and technology innovations. Use its influence to create a new marine fisheries industry that works well together and supports development in different regions, helping the marine fisheries economy grow in a balanced and sustainable way.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, J.W.; Jiang, Z.; Hu, J.Y. Spatio-temporal evolution and driving factors of high-quality marine economic development in China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2024, 79, 3110–3128. [Google Scholar]

- Di, Q.B.; Chen, X.L.; Su, Z.X.; Sun, K. Research on regional disparities in carbon emission efficiency and carbon emission reduction potential of China’s marine fisheries under the “Dual-Carbon” target. Mar. Environ. Sci. 2023, 42, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Z.B.; Wang, H.Y. Effect Test of digital economy development on the construction of a national unified large market. Stat. Decis. 2024, 40, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Feng, W.; Shao, G.L. Spatio-temporal difference of total carbon emission efficiency of fishery in China. Econ. Geogr. 2018, 38, 179–187. [Google Scholar]

- Idda, L.; Madau, A.F.; Pulina, P. Capacity and economic efficiency in small-scale fisheries: Evidence from the Mediterranean Sea. Mar. Policy 2009, 33, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tingley, D.; Pascoe, S.; Coglan, L. Factors affecting technical efficiency in fisheries: Stochastic production frontier versus data envelopment analysis approaches. Fish. Res. 2005, 73, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, P.; Li, J.L.; Cao, L.D.; Liu, Y.C.; Zhang, H.T. Evaluation of China’s fisheries economic efficiency and forecast of development trends. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2023, 44, 160–172. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.; James, L.A.; Chu, J.J. Construction of China’s modern marine fishery industry system: Evaluation based on fishery benefit indicators. Rev. Econ. Res. 2016, 57, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.; Zhu, X. Evaluation and determinants of the digital inclusive financial support efficiency for marine carbon sink fisheries: Evidence from China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, E.M.; Zanaty, N.; Abou El-Magd, I. Potential Efficiency of Earth Observation for Optimum Fishing Zone Detection of the Pelagic Sardinella aurita Species along the Mediterranean Coast of Egypt. Fishes 2022, 7, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howson, P. Building trust and equity in marine conservation and fisheries supply chain management with blockchain. Mar. Policy 2020, 115, 103873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.L.; Ji, X.Q.; Hu, Y.; Cai, X.Z. The spatial-temporal evolution of marine fishery eco-efficiency based on SBM model in China. Ocean Dev. Manag. 2019, 36, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Doloreux, D.; Melançon, Y. Innovation-support organizations in the marine science and technology industry: The case of Quebec’s coastal region in Canada. Mar. Policy 2009, 33, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.H.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, F.X.; Li, J. R&D element flow, spatial knowledge spillovers and economic growth. Econ. Res. J. 2017, 52, 109–123. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, D.; Qi, J.L.; Zhong, W.Y.; Wang, J.W. Urban and rural integration development in urban agglomerations: Measurement and evaluation, obstacle factors and driving factors. Geogr. Res. 2023, 42, 2914–2939. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.Z.; Wang, H.J.; Zhang, B.; Huang, X.X. Analysis on the network structure of urban agglomeration and its influencing factors based on the perspective of multi-dimensional feature flow: Taking Wuhan urban agglomeration as an example. Econ. Geogr. 2021, 41, 68–76. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Liu, G.Y. Does the flow of R&D elements under the compression of time and space improve the efficiency of regional green innovation? Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2021, 38, 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, R.J.; Cheng, Y. Impacts of innovation factor agglomeration on carbon emission efficiency in the Yellow River Basin. Geogr. Res. 2024, 43, 577–595. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.L.; Zhao, B.; Xu, R.Y. Impact of innovation factor flow on energy efficiency. Stat. Res. 2023, 40, 88–97. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, Y.H.; Han, Q. Effects of interregional flow of factors on land green production efficiency: A case study of Wuhan urban agglomeration. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin 2023, 32, 2060–2071. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Q.; Zhang, X.Q.; Lu, G. Research on impact of international factor flow and commodity trade on environmental efficiency. Reg. Res. Dev. 2021, 40, 144–149. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.D.; Wu, D.; Zhou, S.D. Production factor mobility, regional coordination and integration and economic growth. J. Ind. Technol. Econ. 2018, 37, 58–66. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Li, Z. Labor mobility networks and green total factor productivity. Systems 2024, 12, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L. Do the inter-provincial capital flows contribute to regional economic disparities? Econ. Probl. 2020, 3, 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, R.R.; Shen, C.M. Capital Flow, Industrial Agglomeration and Industrial Structure Upgrading-Based on the Panel Data Analysis of 16 Central Cities in Yangtze River Delta. Inq. Into Econ. Issues 2019, 6, 135–142. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, Y.M.; Zeng, G. The role and mechanism of scientific and technological innovation in promoting the transformation of regional economic development models. Geogr. Res. 2017, 36, 2279–2290. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Hu, L.J.; He, F. Factor flow, market integration and economic development-an empirical study based on Chinese provincial panel data. Inq. Into Econ. Issues 2019, 12, 56–69. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Li, X.M.; Huang, S.J. Big data, technical progress and economic growth: An endogenous growth theory introducing data as production factors. Econ. Res. J. 2022, 57, 103–119. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Liu, J.; Lu, X.; Xie, Y.; Wang, Z. Digitalization as a factor of production in China and the impact on total factor productivity (TFP). Systems 2024, 12, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Y.; Zhao, H.L.; Lin, T.Z. Is element flow “structural dividend” or “structural negative interest”? Rev. Econ. Manag. 2018, 34, 57–67. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.W.; Yang, D.P. Factor flow, industrial structure upgrading and regional economic growth. China Dev. 2022, 22, 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, L.; Huang, P.H.; Ou, C.Y. Research on the improvement path of commercialization efficiency of marine scientific and technological achievements from the perspective of innovation ecosystem. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2024, 44, 150–157. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Tang, T.; Deng, M. Strategic alignment of technological innovation for sustainable development: Efficiency evaluation and spatial analysis in China’s advanced manufacturing industry. Systems 2025, 13, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Zhou, D.D.; Zhao, D. Coupling and coordination analysis of high-quality development of the Chinese digital economy and marine economy. Ocean Dev. Manag. 2023, 40, 98–106. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, T.Y.; Lin, H.C.; Liu, W.H. The Fishery Value Chain Analysis in Taiwan. Fishes 2022, 7, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.N.; Bu, Y. Human capital, industrial structure and China’s carbon dioxide emission efficiency-An empirical research based on the SBM and Tobit model. Contemp. Econ. Manag. 2018, 40, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Zhai, L.; Han, L.M.; Zhang, H.Z. Industrial structure adjustment, changes in marine space resources and marine fishery economic growth. Stat. Decis. 2020, 36, 96–100. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T. Evaluation and regional differences of marine fishery production efficiency in China. Inn. Mong. Sci. Technol. Econ. 2024, 14, 42–48. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, G.B.; Zhang, Y.Q. Technology innovation efficiency and influencing factors of the provinces along the Silk Road economic belt. Reg. Res. Dev. 2017, 36, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, T. Mediating effects and moderating effects in causal inference. China Ind. Econ. 2022, 5, 100–120. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Z.L.; Zhu, W.C.; Li, B. Synergistic analysis of economic resilience and efficiency of marine fishery in China. Geogr. Res. 2022, 41, 406–419. [Google Scholar]

- Tone, K. A slacks-based measure of efficiency in data envelopment analysis. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2001, 130, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.J.; Hu, S.L.; Zeng, G.; Chen, P.X.; Wang, J.W.; Wan, Y.Y. Impact mechanism of the digital economy on the green development efficiency in the Yangtze River Delta region. Econ. Geogr. 2025, 45, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- He, H.G.; Li, Y.J.; Dai, Z.Y.; Lin, Q.R. Study on impact of factor mobility on urban-rural integration development-taking the Yangtze River Delta Region as an example. Agric. Econ. Manag. 2024, 1, 76–88. [Google Scholar]

- Ping, W.Y.; Li, W.X.; Luo, L.Q. Research on the influence mechanism and spatial differentiation of factor flow on urban-rural integrated development. J. Stat. Inf. 2024, 39, 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L. Labor migration, industrial transfer and regional industrial agglomeration-an empirical study based on provincial panel data. Collect. Essays Financ. Econ. 2016, 6, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.P.; Chen, Y. The labor flow, capital shift and productivity growth based on Chinese industrial sector’s structure-bonus hypotheses. Stat. Res. 2007, 7, 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, Z.Q. Measurement on the comprehensive opening-up level of regions and provinces’ economy. Stat. Res. 2008, 1, 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Cui, X.J.; Liu, J. Performance analysis of R&D capital input and output in Chinese independent innovation: With discussion of the effects of human capital and intellectual property rights protection. Soc. Sci. China 2007, 2, 32–42+204-205. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Bao, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y. Measurement of urban-rural integration level and its spatial differentiation in China in the new century. Habitat Int. 2021, 117, 102420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.X.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, N. Spatiotemporal evolution of China’s high quality economic development and its driving mechanism of scientific and technological innovation. Resour. Sci. 2021, 43, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Shao, Q. Research on the impact of environmental regulation on the upgrading of marine industrial structure: Based on the mediation effect model analysis. Sci. Technol. Ind. 2023, 23, 145–150. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.Y. The determination and measurement of industrial structure equilibrium: Theoretical explanation and verification. Ind. Econ. Res. 2011, 3, 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Ruan, J.J.; Zhuang, H.T. Impact of digital intelligence on green development in the Yangtze River Delta urban agglomeration. Econ. Geogr. 2024, 44, 123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.B.; Kong, L.X. The influence of urban digital economy development on the level of manufacturing agglomeration. Econ. Geogr. 2023, 43, 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L.C.; Chen, X.S. The impact of government expenditure on science and technology on urban economic resilience: A case study of the Yangtze River Delta urban agglomeration. Stat. Decis. 2025, 41, 147–152. [Google Scholar]

| Primary Indicator | Secondary Indicators | Tier-Three Indicators | Proxy Indicator |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic efficiency of marine fisheries | Input indicators | Resource allocation Capital investment labor input | Marine aquaculture region (hectares) Marine fish fry quantity (ten thousand) Year-end fleet size of ocean-going fishing vessels (units) Marine fisheries personnel (persons) |

| Output indicators | Expected output Unanticipated outputs | Total output value of marine fisheries (ten thousand yuan) Total economic losses from marine products (ten thousand yuan) | |

| Factor mobility | Labor factor | Labor factor mobility ratio | Employment in primary, secondary, and tertiary industries/Total regional population |

| Capital factor | Capital factor mobility ratio | Regional fixed asset investment/Regional gross domestic product | |

| Technology factor | Share of science and technology expenditures | Science and technology expenditures/General public budget expenditures | |

| Data factor | Information and communication capabilities | Mobile telephone switching capacity (ten thousand households) |

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 |

|---|---|---|

| EEMF | EEMF | |

| FM | 0.2554 *** | 0.0825 *** |

| (6.3457) | (2.7174) | |

| Pop | 0.0000 * | |

| (1.7500) | ||

| Hum | 6.9090 *** | |

| (4.3651) | ||

| For | −0.1262 | |

| (−1.0101) | ||

| Fin | 0.4279 ** | |

| (2.0815) | ||

| Ope | −0.0956 ** | |

| (−2.5243) | ||

| Constant | −0.8374 *** | −0.3650 *** |

| (−5.2579) | (−3.0105) | |

| Sigma_u | 0.1173 *** | 0.0440 *** |

| (4.1480) | (3.4904) | |

| Sigma_e | 0.0662 *** | 0.0632 *** |

| (18.0291) | (17.9227) | |

| N | 176 | 176 |

| Variable | Phase One | Phase Two |

|---|---|---|

| FM | EEMF | |

| FM | 0.4187 ** | |

| (2.60) | ||

| Iv | 0.6710 *** | |

| (8.09) | ||

| Pop | 0.0001 | 0.00002 |

| (0.43) | (0.88) | |

| Hum | 4.5104 | −13.1027 ** |

| (0.99) | (−2.63) | |

| For | 0.4330 | −1.2957 ** |

| (1.36) | (−2.83) | |

| Fin | −0.5778 | 0.7689 |

| (−1.02) | (1.17) | |

| Ope | −0.0151 | 0.0945 |

| (−0.16) | (−1.44) | |

| Year fixed effect | Yes | Yes |

| Regional fixed effect | Yes | Yes |

| Kleibergen-Paap rk Wald F statistic | 65.422 | |

| {16.38} | ||

| Kleibergen-Paap rk LM statistic | 6.5740 *** | |

| [0.0103] | ||

| N | 165 | 165 |

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Shorten the Time Window | Increase Control Variables | |

| FM | 0.0428 * | 0.0637 * |

| (1.6562) | (1.9282) | |

| Pop | 0.0000 ** | 0.0000 |

| (2.0966) | (1.0375) | |

| Hum | 3.2675 * | 5.9899 *** |

| (1.8375) | (3.1841) | |

| For | 0.1813 | −0.1347 |

| (1.3225) | (−1.0830) | |

| Fin | 0.4711 *** | 0.3954 * |

| (2.9348) | (1.8925) | |

| Ope | −0.0894 *** | −0.0832 ** |

| (−2.6228) | (−2.1918) | |

| Soc | 0.1630 | |

| (0.9377) | ||

| Mar | 0.6644 | |

| (1.5621) | ||

| Constant | −0.1789 * | −0.3332 *** |

| (−1.6598) | (−2.6652) | |

| sigma_u | 0.0344 *** | 0.0424 *** |

| (3.8755) | (3.3918) | |

| sigma_e | 0.0492 *** | 0.0629 *** |

| (15.5098) | (17.8882) | |

| N | 132 | 176 |

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| EEMF | Stl | Iso | |

| FM | 0.0666 *** | 1.6100 *** | 0.0246 *** |

| (3.0788) | (11.5182) | (9.7018) | |

| Pop | 0.0000 ** | 0.0001 | 0.0000 *** |

| (2.4427) | (1.3832) | (5.8454) | |

| Hum | 4.3175 *** | 60.1265 *** | 0.5176 *** |

| (4.4142) | (9.5100) | (4.5146) | |

| For | −0.1094 | −1.2839 | 0.0444 ** |

| (−0.7521) | (−1.3659) | (2.6028) | |

| Fin | 0.6764 *** | 2.8522 *** | 0.0770 *** |

| (5.2015) | (3.3932) | (5.0495) | |

| Ope | −0.0726 ** | 0.7351 *** | 0.0077 ** |

| (−2.4915) | (3.9007) | (2.2529) | |

| Constant | −0.3005 *** | −6.4085 *** | 0.4077 *** |

| (−2.8587) | (−9.4313) | (33.0809) | |

| N | 176 | 176 | 176 |

| R2 | 0.296 | 0.600 | 0.598 |

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Northern Marine Economic Circle | Eastern Marine Economic Circle | Southern Marine Economic Circle | |

| FM | 0.1128 ** | 0.3716 *** | 0.0267 |

| (2.1059) | (3.5023) | (0.4861) | |

| Pop | −0.0000 | 0.0000 * | −0.0002 |

| (−0.1500) | (1.8432) | (−1.5416) | |

| Hum | 4.8246 | −0.3349 | 8.7182 *** |

| (1.4029) | (−0.0676) | (3.2782) | |

| For | −0.6073 ** | 0.2593 | −0.0822 |

| (−2.3088) | (0.9922) | (−0.5138) | |

| Fin | 0.8522 * | 0.3015 | 0.2610 |

| (1.9322) | (0.5274) | (0.8799) | |

| Ope | 0.1076 | 0.0130 | −0.0503 |

| (0.7564) | (0.1769) | (−0.9159) | |

| Constant | −0.5633 ** | −1.4441 *** | −0.0742 |

| (−2.2256) | (−3.6877) | (−0.3971) | |

| Sigma_u | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0303 |

| (0.0000) | (0.0000) | (1.6295) | |

| Sigma_e | 0.0661 *** | 0.0537 *** | 0.0578 *** |

| (11.3137) | (9.7980) | (10.6144) | |

| N | 64 | 48 | 64 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhao, L.; Liu, J.; Xu, S. Research on the Impact of Factor Mobility on the Economic Efficiency of Marine Fisheries in China’s Coastal Regions. Fishes 2026, 11, 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11020089

Zhao L, Liu J, Xu S. Research on the Impact of Factor Mobility on the Economic Efficiency of Marine Fisheries in China’s Coastal Regions. Fishes. 2026; 11(2):89. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11020089

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Liangshi, Jiaqi Liu, and Shuting Xu. 2026. "Research on the Impact of Factor Mobility on the Economic Efficiency of Marine Fisheries in China’s Coastal Regions" Fishes 11, no. 2: 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11020089

APA StyleZhao, L., Liu, J., & Xu, S. (2026). Research on the Impact of Factor Mobility on the Economic Efficiency of Marine Fisheries in China’s Coastal Regions. Fishes, 11(2), 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11020089