Cooperative Associations Between Fishes and Bacteria: The Influence of Different Ocean Fishes on the Gut Microbiota Composition

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

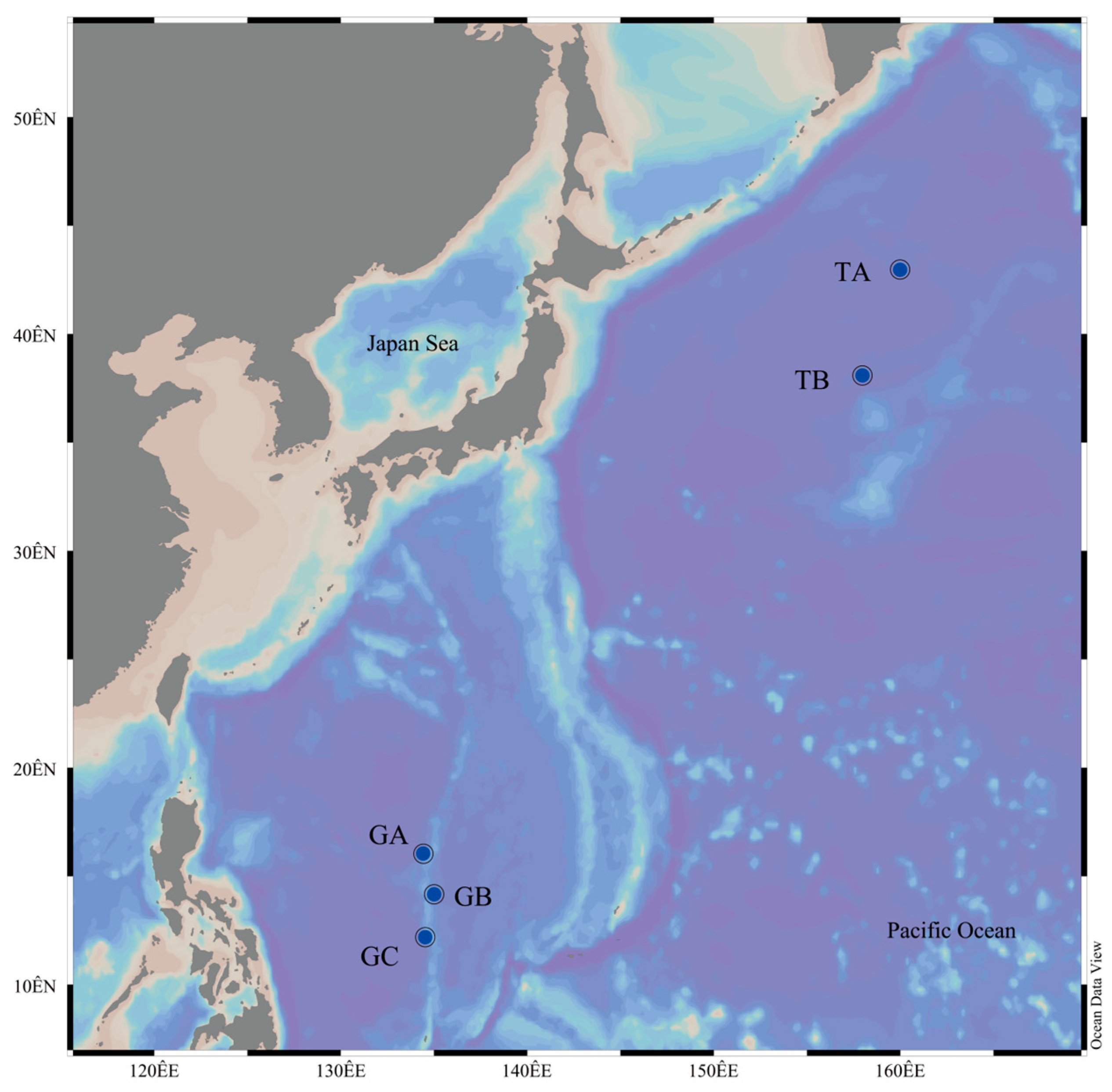

2.1. Collection of Samples

2.2. DNA Extraction and Sequencing

2.3. Amplicon Processing and OTU Clustering

2.4. Statistical Analyses

2.5. Function Prediction

3. Results

3.1. Sequencing Information Statistics

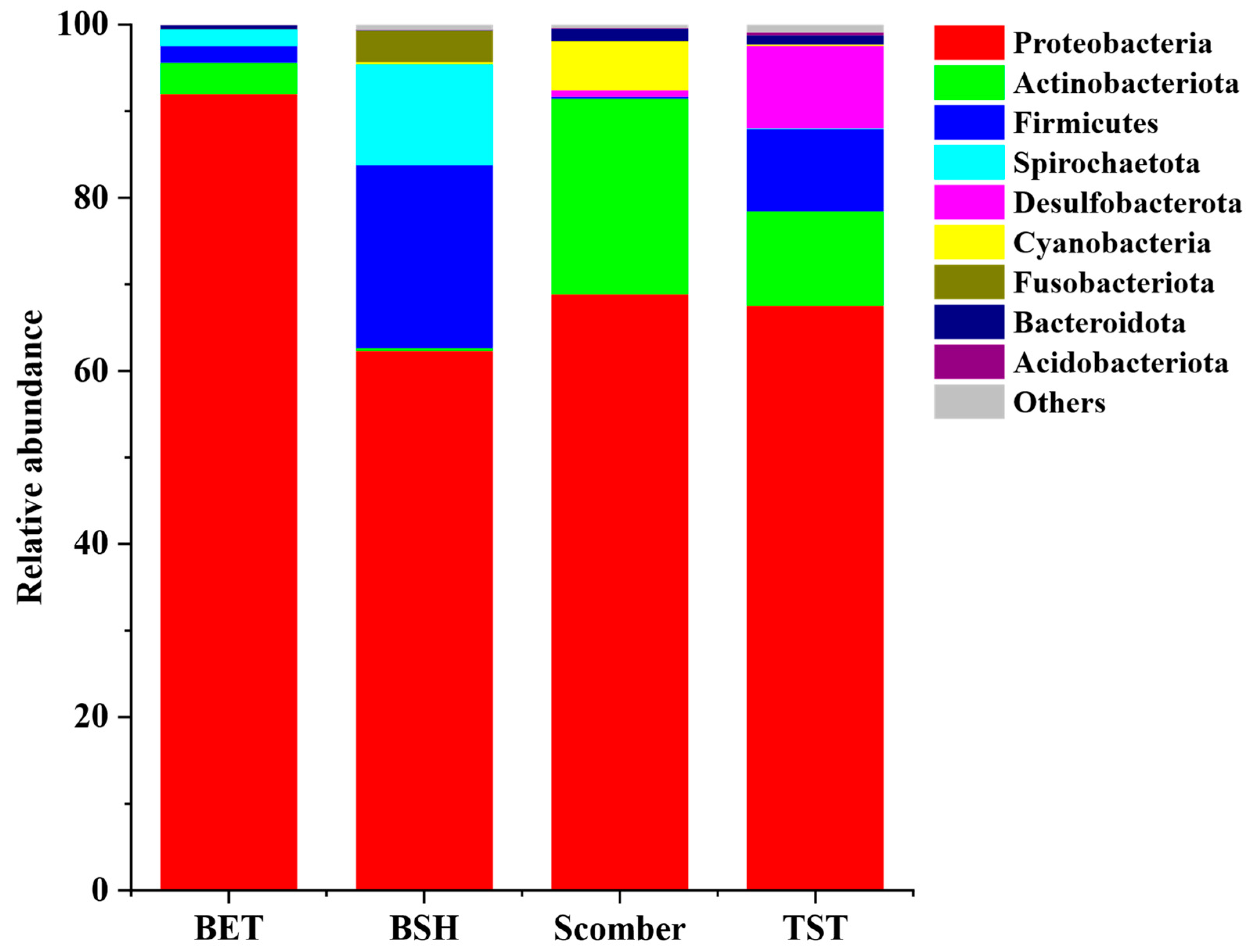

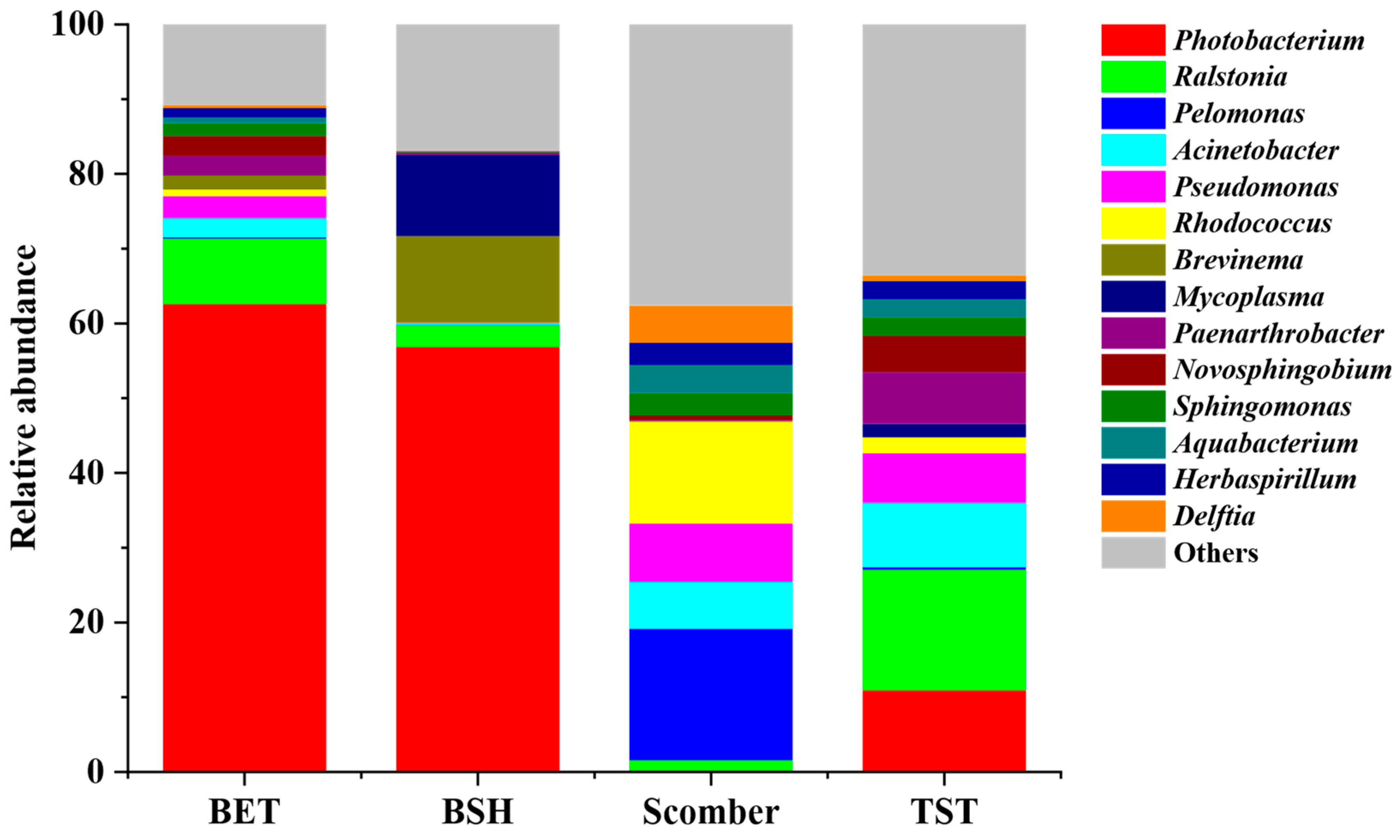

3.2. Dominant Gut Microbiota of Blue Shark, Bigeye Tuna, Sickle Pomfret and Mackerel

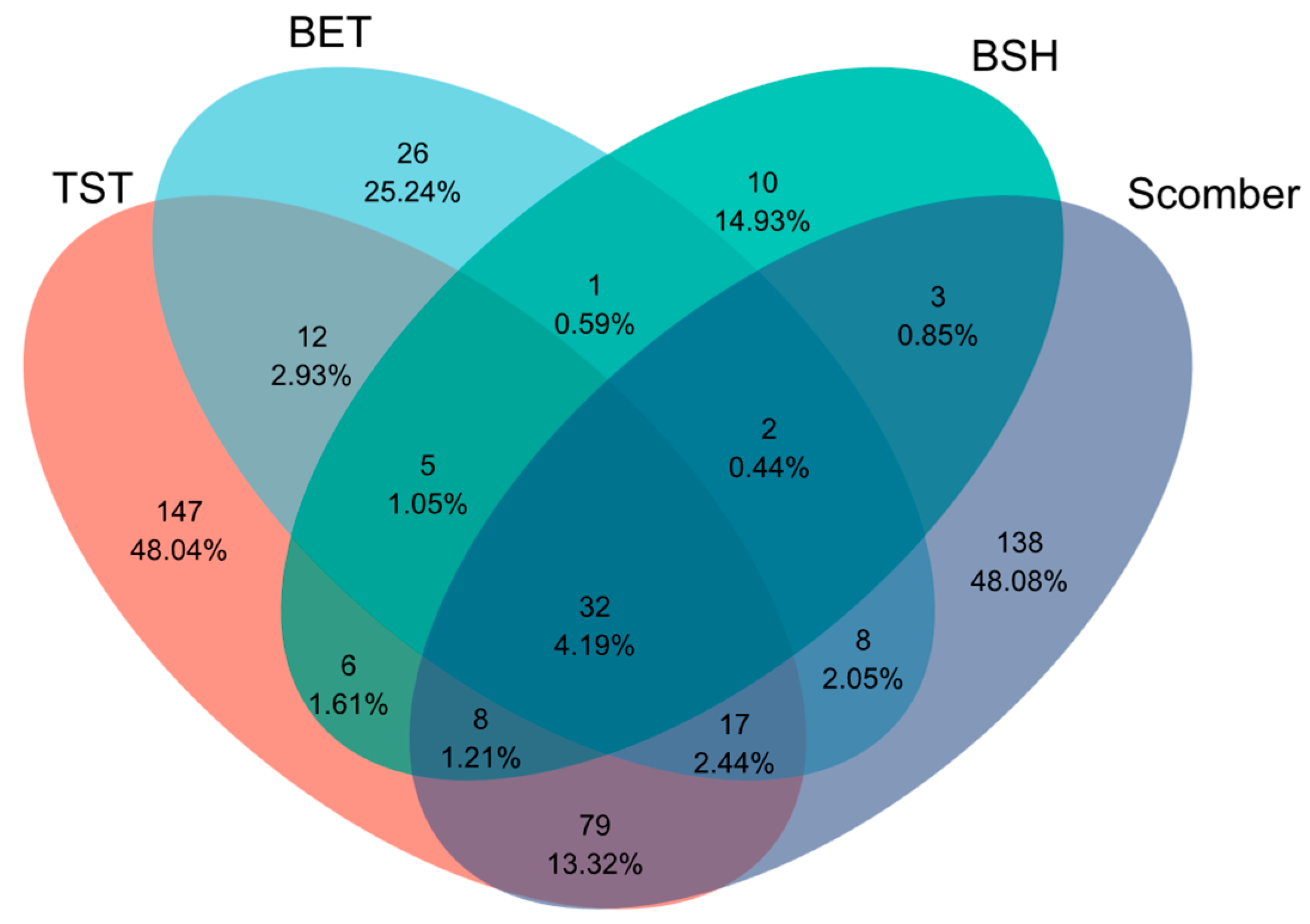

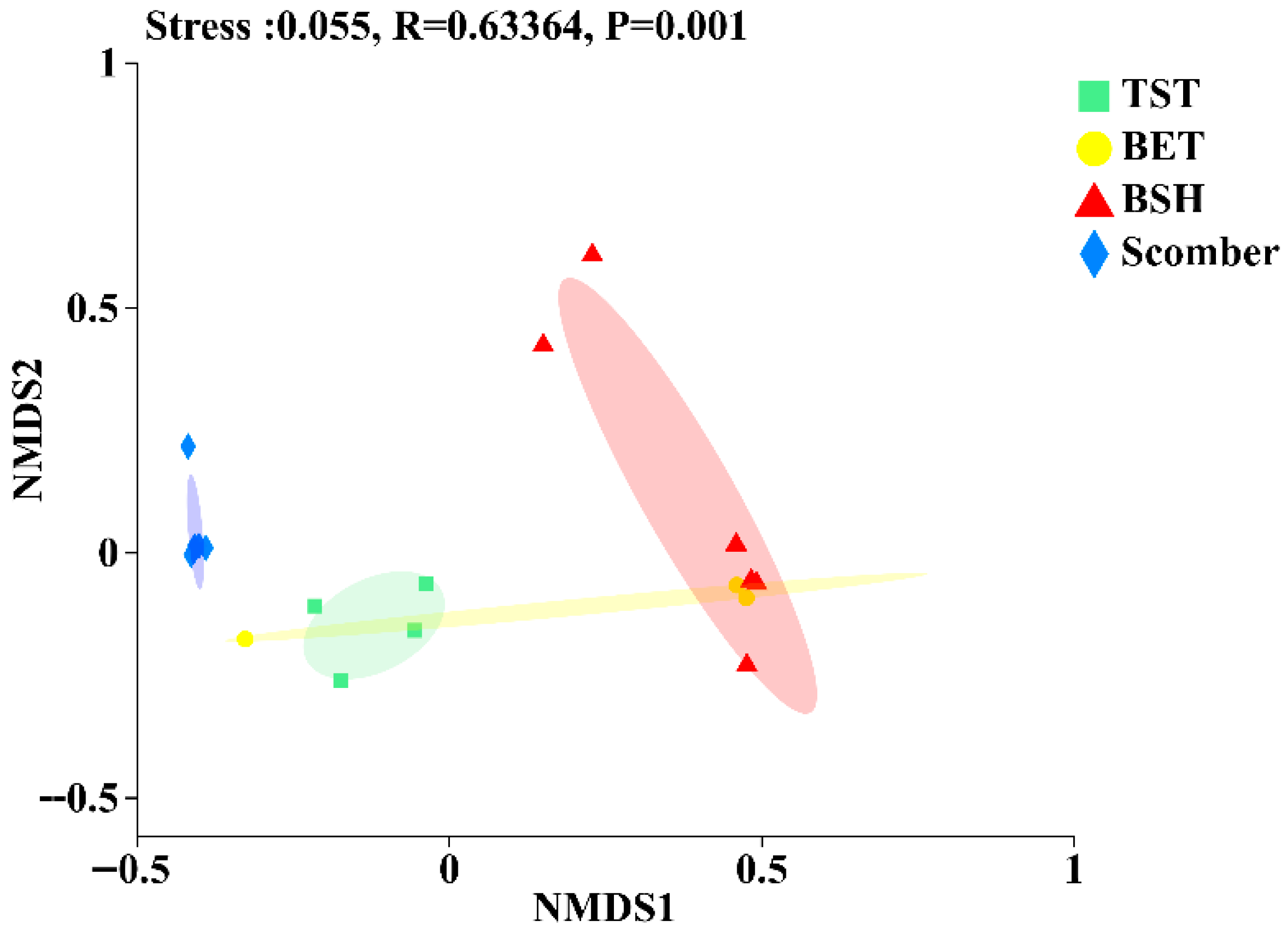

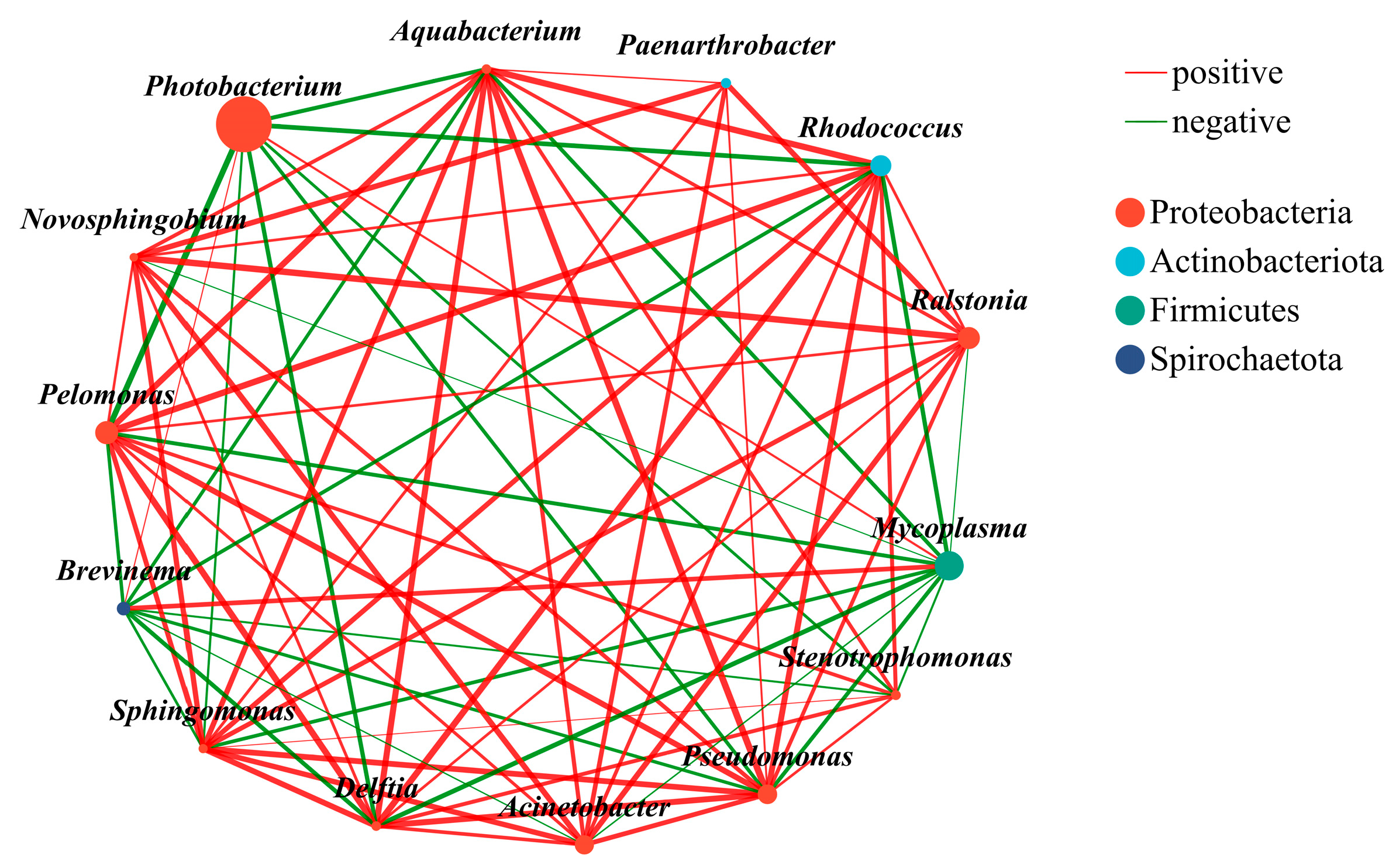

3.3. Differences in Fish Intestinal Microbiota Stability

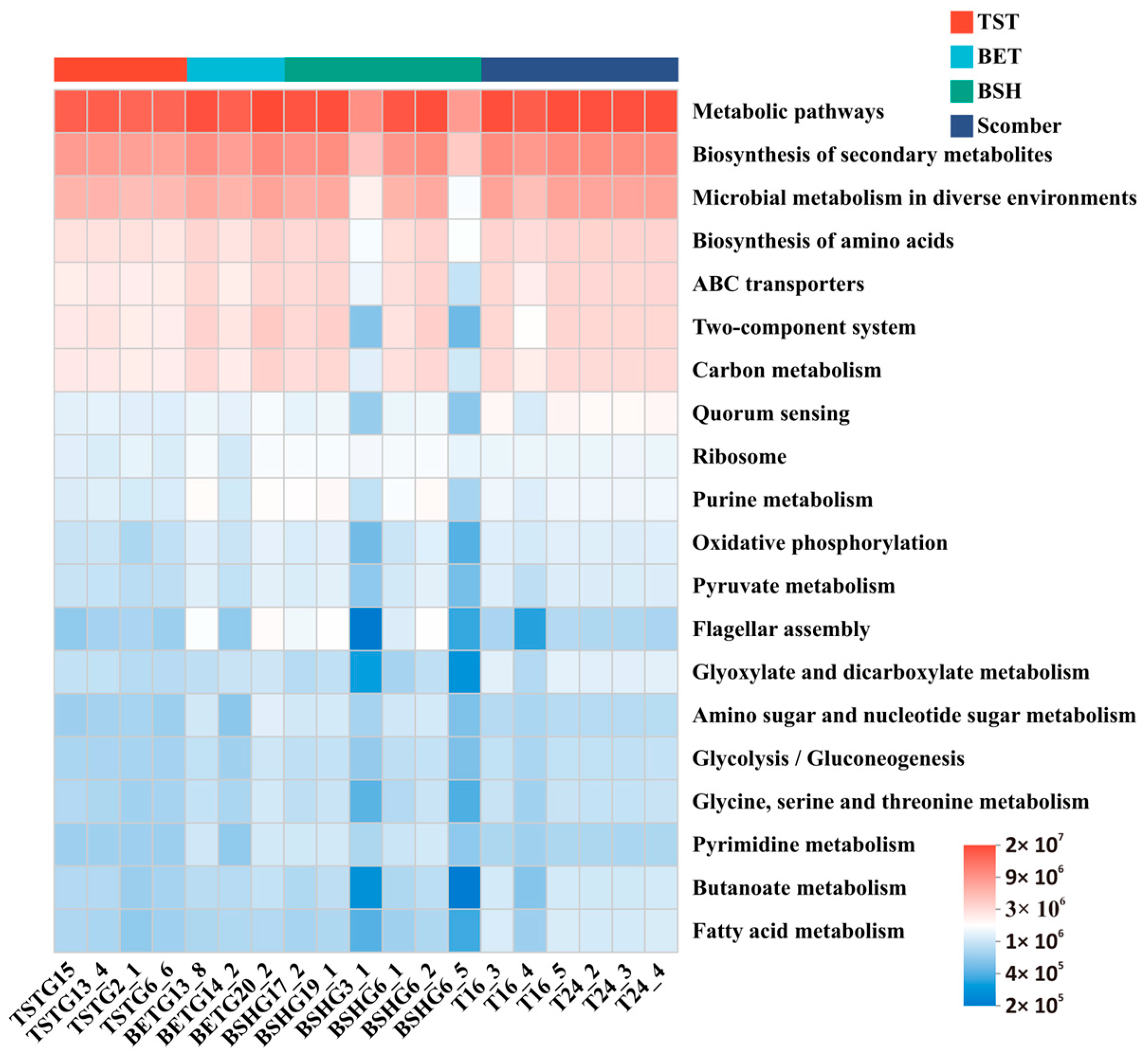

3.4. Shared Dominant Functions Across Different Fish Species Were Associated Primarily with Energy Metabolism

4. Discussion

4.1. Blue Shark, Bigeye Tuna, Sickle Pomfret and Mackerel Gut Microbial Communities

4.2. Functional Roles of the Gut Microbiota in Host Energy Acquisition

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Diwan, A.D.; Harke, S.N.; Panche, A.N. Host-microbiome interaction in fish and shellfish: An overview. Fish Shellfish. Immunol. Rep. 2023, 4, 100091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Wang, C.; Liu, P.; Li, D.; Li, Y.; Ma, X. Dietary fiber gap and host gut microbiota. Protein Pept. Lett. 2017, 24, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunagawa, S.; Coelho, L.P.; Chaffron, S.; Kultima, J.R.; Labadie, K.; Salazar, G.; Djahanschiri, B.; Zeller, G.; Mende, D.R.; Alberti, A.; et al. Ocean plankton. Structure and function of the global ocean microbiome. Science 2015, 348, 1261359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van de Wouw, M.; Schellekens, H.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis: Modulator of host metabolism and appetite. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 727–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Wang, H.; Lan, Y.; Zhong, C.; Yan, G.; Xu, Z.; Lu, G.; Chen, J.; Wei, T.; Wong, W.C.; et al. Changes in community structures and functions of the gut microbiomes of deep-sea cold seep mussels during in situ transplantation experiment. Anim. Microbiome 2023, 5, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, A.R.; Stephens, W.Z.; Stagaman, K.; Wong, S.; Rawls, J.F.; Guillemin, K.; Bohannan, B.J. Contribution of neutral processes to the assembly of gut microbial communities in the zebrafish over host development. ISME J. 2016, 10, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wu, J.; Du, H.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Wei, Q. Quantifying the colonization of environmental microbes in the fish gut: A case study of wild fish populations in the Yangtze River. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 828409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avella, M.A.; Place, A.; Du, S.J.; Williams, E.; Silvi, S.; Zohar, Y.; Carnevali, O. Lactobacillus rhamnosus accelerates zebrafish backbone calcification and gonadal differentiation through effects on the GnRH and IGF systems. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e45572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Chen, M. Global research progress of gut microbiota and epigenetics: Bibliometrics and visualized analysis. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1412640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Näpflin, K.; Schmid-Hempel, P. Host effects on microbiota community assembly. J. Anim. Ecol. 2018, 87, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhou, L.; Yu, Y.; Ni, J.; Xu, W.; Yan, Q. Composition of gut microbiota in the gibel carp (Carassius auratus gibelio) varies with host development. Microb. Ecol. 2017, 74, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, M.; Gao, C.X.; Dai, X.J.; Wu, F. Preliminary analysis of biology for the blue shark, (Prionace glauca), in the southwest Indian Ocean. J. Ocean China 2017, 26, 271–277. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Shao, K.; Lai, C. Latin-Chinese Dictionary of Fish Names by Classification System; Sueichan Press: Keelung, Taiwan, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Robins, C.R.; Smith, M.M.; Heemstra, P.C. Smiths’ Sea Fishes; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Du, J.; Ye, G.; Zhou, Q.; Chen, B.; Hu, W.; Zheng, X. Progress and prospects of coastal ecological connectivity studies. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2015, 35, 6923–6933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desjardins, P.; Conklin, D. NanoDrop microvolume quantitation of nucleic acids. J. Vis. Exp. 2010, 45, 2565. [Google Scholar]

- Abellan-Schneyder, I.; Matchado, M.S.; Reitmeier, S.; Sommer, A.; Sewald, Z.; Baumbach, J.; List, M.; Neuhaus, K. Primer, Pipelines, Parameters: Issues in 16S rRNA gene sequencing. mSphere 2021, 6, e01202-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strathdee, F.; Free, A. Denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE). Methods Mol. Biol. 2013, 1054, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chan, J.; Geng, D.; Pan, B.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, Q. Gut microbial divergence between three hadal amphipod species from the isolated hadal trenches. Microb. Ecol. 2022, 84, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Qu, M.; Liu, Y.; Schneider, R.F.; Song, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, H.; Zhang, S.; et al. Genomic basis of evolutionary adaptation in a warm-blooded fish. Innovation 2022, 3, 100185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dapa, T.; Xavier, K.B. Effect of diet on the evolution of gut commensal bacteria. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2369337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labella, A.M.; Borrego, J.J. Photobacterium. In Bergey’s Manual of Systematics of Archaea and Bacteria; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Berean, K.J.; Burgell, R.E.; Muir, J.G.; Gibson, P.R. Intestinal gases: Influence on gut disorders and the role of dietary manipulations. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 733–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.K.; Gao, X.D.; Wang, L.Y.; Fang, L. Trophic niche partitioning of pelagic sharks in Central Eastern Pacific inferred from stable isotope analysis. J. Appl. Ecol. 2018, 29, 309–313. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, T.; Boutin, S.; Humphries, M.M.; Dantzer, B.; Gorrell, J.C.; Coltman, D.W.; McAdam, A.G.; Wu, M. Seasonal, spatial, and maternal effects on gut microbiome in wild red squirrels. Microbiome 2017, 5, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonoyama, K.; Fujiwara, R.; Takemura, N.; Ogasawara, T.; Watanabe, J.; Ito, H.; Morita, T. Response of gut microbiota to fasting and hibernation in Syrian hamsters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 6451–6456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekirov, I.; Russell, S.L.; Antunes, L.C.; Finlay, B.B. Gut microbiota in health and disease. Physiol. Rev. 2010, 90, 859–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, C.L.; Weir, T.L. The gut microbiota at the intersection of diet and human health. Science 2018, 362, 776–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battley, P.F.; Piersma, T.; Dietz, M.W.; Tang, S.; Dekinga, A.; Hulsman, K. Empirical evidence for differential organ reductions during trans-oceanic bird flight. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2000, 267, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, A.; Mazmanian, S.K. Disruption of the gut microbiome as a risk factor for microbial infections. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2013, 16, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Risely, A.; Waite, D.W.; Ujvari, B.; Hoye, B.J.; Klaassen, M. Active migration is associated with specific and consistent changes to gut microbiota in Calidris shorebirds. J. Anim. Ecol. 2018, 87, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Liu, B.; Wu, H.; Feng, J.; Jiang, T. Seasonal dietary shifts alter the gut microbiota of avivorous bats: Implication for adaptation to energy harvest and nutritional utilization. mSphere 2021, 6, e0046721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, K.R.; Schluter, J.; Coyte, K.Z.; Rakoff-Nahoum, S. The evolution of the host microbiome as an ecosystem on a leash. Nature 2017, 548, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Besten, G.; van Eunen, K.; Groen, A.K.; Venema, K.; Reijngoud, D.J.; Bakker, B.M. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. J. Lipid Res. 2013, 54, 2325–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papastamatiou, Y.P.; Watanabe, Y.Y.; Bradley, D.; Dee, L.E.; Weng, K.C.; Lowe, C.G.; Caselle, J.E. Drivers of Daily Routines in an Ectothermic Marine Predator: Hunt Warm, Rest Warmer? PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, J.G.; Beichman, A.C.; Roman, J.; Scott, J.J.; Emerson, D.; McCarthy, J.J.; Girguis, P.R. Baleen whales host a unique gut microbiome with similarities to both carnivores and herbivores. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, K.Y.; Zou, X. Carbohydrate-Protein Interactions: Advances and Challenges. Commun. Inf. Syst. 2021, 21, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, J.; Liu, B.; Liu, Y.; Wei, Y. Cooperative Associations Between Fishes and Bacteria: The Influence of Different Ocean Fishes on the Gut Microbiota Composition. Fishes 2026, 11, 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010065

Liu J, Liu B, Liu Y, Wei Y. Cooperative Associations Between Fishes and Bacteria: The Influence of Different Ocean Fishes on the Gut Microbiota Composition. Fishes. 2026; 11(1):65. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010065

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Jintao, Bilin Liu, Yang Liu, and Yuli Wei. 2026. "Cooperative Associations Between Fishes and Bacteria: The Influence of Different Ocean Fishes on the Gut Microbiota Composition" Fishes 11, no. 1: 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010065

APA StyleLiu, J., Liu, B., Liu, Y., & Wei, Y. (2026). Cooperative Associations Between Fishes and Bacteria: The Influence of Different Ocean Fishes on the Gut Microbiota Composition. Fishes, 11(1), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11010065