β,β-Dimethylacrylshikonin Alleviates Zebrafish (Danio rerio) Soyasaponin-Induced Enteritis by Maintaining Intestinal Homeostasis and Improving Intestinal Immunity and Metabolism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Ethics Statement

2.2. Zebrafish, Diets, and Feeding Trial

2.3. Sampling

2.4. RT-qPCR and Tissue Sections Were Used to Screen for the Optimal Dosage

2.5. Histological Analysis

2.6. 16S rRNA Sequencing Analysis of Gut Microbial Community

2.7. Transcriptome Sequencing

2.8. RT-qPCR

2.8.1. RT-qPCR Validation

2.8.2. Verification of DEGs in Immune- and Lipid Metabolism-Related Pathways

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Result

3.1. Growth Performance

3.2. Relative mRNA Expression of il1β, il8, and il10

3.3. β,β-Dimethylacrylshikonin’s Effect on the Intestinal Pathology of Zebrafish SBMIE

3.4. Intestinal Microbiota Analysis

3.5. Results from Transcriptome Sequencing Analysis

3.5.1. DEGs

3.5.2. Intestinal DEG-Associated Enriched GO Annotations and KEGG Pathways

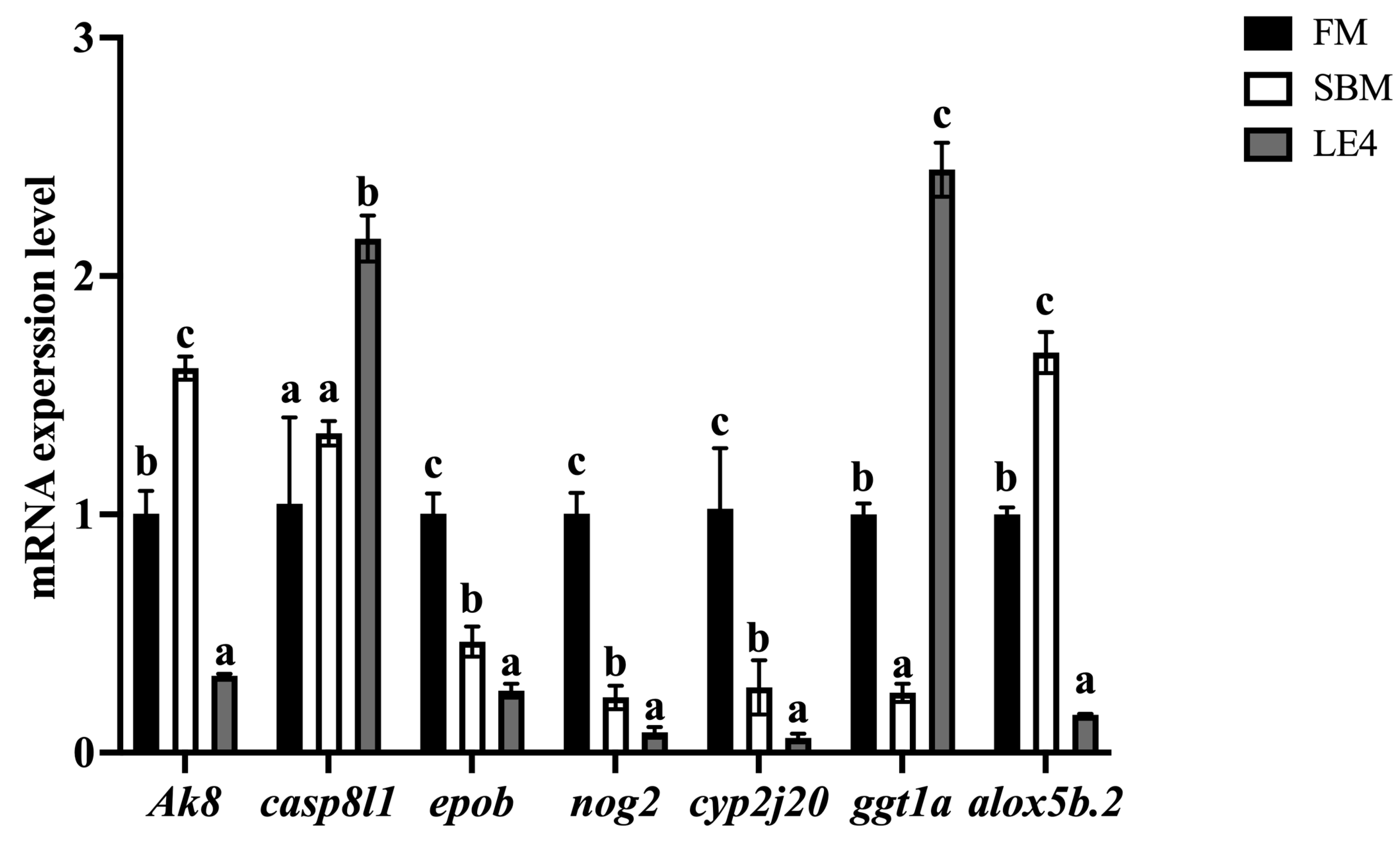

3.6. Validation of the Immune-Associated and Lipid Metabolism-Associated Pathways by RT-qPCR

4. Discussion

4.1. Alleviating Effect of β,β-Dimethylacrylshikonin on SBMIE

4.2. β,β-Dimethylacrylshikonin Alleviates SBMIE by Regulating Intestinal Microbial Composition, Enhancing Immunity, and Improving Metabolism

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hedrera, M.I.; Galdames, J.A.; Jimenez-Reyes, M.F.; Reyes, A.E.; Avendaño-Herrera, R.; Jaime, R.; Carmen, G.F. Soybean Meal Induces Intestinal Inflammation in Zebrafish Larvae. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e69983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.H.; Zhao, Y.B.; Huang, Z.F.; Long, Z.Y.; Qin, H.H.; Lin, H.; Zhou, S.S.; Kong, L.M.; Ma, J.R.; Lin, Y.; et al. Dietary supplementation of Lycium barbarum polysaccharides alleviates soybean meal-induced enteritis in spotted sea bass Lateolabrax maculatus. Animal Nutr. 2025, 20, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Li, M.; Ye, W.; Shan, J.; Zhao, X.; Duan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Unger, B.H.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, W.; et al. Sinomenine Hydrochloride Ameliorates Fish Foodborne Enteritis via α7nAchR-Mediated Anti-inflammatory Effect whilst Altering Microbiota Composition. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 766845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krogdahl, Å.; Penn, M.; Thorsen, J.; Refstie, S.; Bakke, A.M. Important antinutrients in plant feedstuffs for aquaculture: An update on recent findings regarding responses in salmonids. Aquac. Res. 2010, 41, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Ingh, T.S.G.A.M.; Krogdahl, Å.; Olli, J.J.; Hendriks, H.G.C.J.M.; Koninkx, J.G.J.F. Effects of soybean-containing diets on the proximal and distal intestine in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar): A morphological study. Aquaculture 1991, 94, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumsey, G.L.; Siwicki, A.K.; Anderson, D.P.; Bowser, P.R. Effect of soybean protein on serological response, non-specific defense mechanisms, growth, and protein utili-zation in rainbow trout, Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1994, 41, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Wang, B.; Cui, Z.W.; Zhang, X.Y.; Cheng, Y.Y.; Xu, X.; Li, X.-M.; Wang, Z.-X.; Chen, D.-D.; Zhang, Y.-A. Integrative Transcriptomic and Micrornaomic Profiling Reveals Immune Mechanism for the Resilience to Soybean Meal Stress in Fish Gut and Liver. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Xu, X.; Wang, B.; Li, X.M.; Cheng, Y.Y.; Li, M.; Xia, X.-Q.; Zhang, Y.-A. Anti-Foodborne Enteritis Effect of Galantamine Potentially via Acetylcholine Anti-Inflammatory Pathway in Fish. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020, 97, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merrifield, D.L.; Olsen, R.E.; Myklebust, R.; Ringø, E. Dietary effect of soybean (Glycine max) products on gut histology and microbiota of fish. Soybean Nutr. 2011, 231, e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hu, Y.J.; Zhang, J.Z.; Xue, J.J.; Chu, W.Y.; Hu, Y. Effects of dietary soy isoflavone and soy saponin on growth performance, intestinal structure, intestinal immunity and gut microbiota community on rice field eel (Monopterus albus). Aquaculture 2021, 537, 736506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, I.T.; Gee, J.M.; Price, K.; Curl, C.; Fenwick, G.R. Influence of saponins on gut permeability and active nutrient transport in vitro. J. Nutr. 1986, 116, 2270–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.; Pan, S.H.; Li, Q.; Qi, Z.Z.; Deng, W.Z.; Bai, N. Protective effects of glutamine against soy saponins-induced enteritis, tight junction disruption, oxidative damage and autophagy in the intestine of Scophthalmus maximus L. Aquaculture 2021, 114, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Ringø, E.; Olsen, R.E.; Song, S.K. Dietary effects of soybean products on gut microbiota and immunity of aquatic animals: A review. Aquac. Nutr. 2018, 24, 644–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.; Jia, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Bai, N.; Xu, X.; Xu, B. Soya-saponins induce intestinal inflammation and barrier dysfunction in juvenile turbot (Scophthalmus maximus). Fish Shellfish. Immunol. 2018, 77, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinow, M.R.; McLaughlin, P.; Papworth, L.; Stafford, C.; Kohler, G.O.; Livingston, A.L.; Cheeke, P.R. Effect of alfalfa saponins on intestinal cholesterol absorption in rats. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1977, 30, 2061–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.; Kortner, T.M.; Penn, M.; Hansen, A.K.; Krogdahl, Å. Effects of dietary plant meal and soya-saponin supplementation on intestinal and hepatic lipid droplet accumulation and lipoprotein and sterol metabolism in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.). Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 111, 432–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Zhao, X.; Xie, J.; Tong, X.; Shan, J.; Shi, M.; Wang, G.; Ye, W.; Liu, Y.; Unger, B.H.; et al. Dietary Inclusion of Seabuckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides) Mitigates Foodborne Enteritis in Zebrafish Through the Gut-Liver Immune Axis. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 831226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Kianann, T.; Gong, Q.F.; Peng, Y.H.; Liang, M.Z.; Xu, P.; Liang, X.Y.; Liu, W.J.; Wu, Y.R.; Cai, X.H. Positive effects of Lithospermum erythrorhizon extract added to high soybean meal diet on growth, intestinal antioxidant capacity, intestinal microbiota, and metabolism of pearl gentian grouper. Aquac. Rep. 2024, 39, 102500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, G. Activation of CaMKKβ-AMPK-mTOR pathway is required for autophagy induction by β,β-dimethylacrylshikonin against lung adenocarcinoma cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 517, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, S.Y.; Jeong, Y.; Kim, B.Y.; Lee, J.; Ahn, H.J.; Jeong, J.H.; Kim, M.S.; Kim, J.; Han, Y.H. β,β--Dimethylacrylshikonin sensitizes human colon cancer cells to ionizing radiation through the upregulation of reactive oxygen species. Oncol. Lett. 2014, 7, 1812–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, S.; Tajima, M.; Tsukada, M.; Tabata, M. A comparative study on anti-inflammatory activities of the enantiomers, shikonin and alkannin. J. Nat. Prod. 1986, 49, 466–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yang, L.; Zhang, N.; Turpin, J.A.; Buckheit, R.W.; Osterling, C.; Oppenheim, J.J.; Howard, O.M.Z. Shikonin, a Component of Chinese Herbal Medicine, Inhibits Chemokine Receptor Function and Suppresses Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003, 47, 2810–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, F.N.; Lee, Y.S.; Kuo, S.C.; Chang, Y.S.; Teng, C.M. Inhibition on platelet activation by shikonin derivatives isolated from Arnebia euchroma. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1995, 1268, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.C.; Syu, W.J.; Li, S.Y.; Lin, C.H.; Lee, G.H.; Sun, C.M. Antimicrobial activities of naphthazarins from Arnebia euchroma. J. Nat. Prod. 2002, 65, 1857–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.L. Therapeutic Effect of Hydroxynaphthoquinone from Shikonin Sinensis on Dextran Sodium-Induced Ulcerative Colitis in Mice. Ph.D. Dissertation, Jilin University, Jili, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, K.; Shi, P.; Zhang, L.; Yan, X.K.; Xu, J.L.; Liao, K. Trans-cinnamic acid alleviates high-fat diet-induced renal injury via JNK/ERK/P38 MAPK pathway. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2025, 135, 109769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, M.D.; Yang, K.; Wang, X.; Liu, C.D.; Zhou, H.H.; Mai, K.S.; He, G. The modulation of mTOR signaling on dietary carbohydrate utilization in largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). J. Nutr. Biochem. 2025, 145, 110008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.Y.; Zhang, L.; Wu, N.; Liu, Y.H.; Xie, J.Y.; Su, L.; Zhu, Q.S.; Unger, B.H.; Altaf, F.; Hu, Y.H.; et al. Gallic acid acts as an anti-inflammatory agent via PPARγ-mediated immunomodulation and antioxidation in fish gut-liver axis. Aquaculture 2024, 578, 740142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Xie, J.Y.; Zhao, X.Y.; Li, X.M.; Wang, R.; Shan, J.W.; Cheng, Y.Y.; Zhang, W.T.; Wu, N.; Xia, X.Q. Establishing the foodborne-enteritis zebrafish model and imaging the involved immune cells’ response. Acta Hydrobiol. Sinica 2022, 46, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerfield, M. The Zebrafish Book: A Guide for the Laboratory Use of the Zebrafish (Danio Rerio), 2.1; Eugene, Ed.; University of Oregon Press: Eugene, OR, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.; Wu, Y.R.; Peng, Y.H.; Liu, W.J.; Liu, M.; Xu, P.; Kianann, T.; Liang, X.Y.; Cai, X.H.; Gong, Q.F. Effects of Sophora flavescens dietary supplementation on the growth performance, haematological indices, and intestinal bacterial community of Oreochromis niloticus. J. Fish Biol. 2024, 105, 1830–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lickwar, C.R.; Camp, J.G.; Weiser, M.; Cocchiaro, J.L.; Kingsley, D.M.; Furey, T.S.; Sheikh, S.Z.; Rawls, J.F. Genomic Dissection of Conserved Transcriptional Regulation in Intestinal Epithelial Cells. PLoS Biol. 2017, 15, e2002054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Xu, L.; Wang, Q.; Feng, J. Gut-Liver Immune Response and Gut Microbiota Profiling Reveal the Pathogenic Mechanisms of Vibrio Harveyi in Pearl Gentian Grouper (Epinephelus Lanceolatus × E. Fuscoguttatus). Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 607754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, M.Q.; Lan, Z.Y.; Peng, Y.H.; He, J.X.; Lu, X.; Li, J.; Xu, P.; Wu, X.Z.; Cai, X.H. Identification and functional characterization of complement regulatory protein CD59 in golden pompano (Trachinotus ovatus). Fish Shellfish. Immunol. 2022, 131, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, M.Q.; Peng, Y.H.; Tan, K.N.; Lan, Z.Y.; Guo, X.Y.; Huang, F.P.; Xu, P.; Yang, S.Y.; Kwan, K.Y.; Cai, X.H. Molecular characterization of complement regulatory factor CD46 in Trachinotus ovatus and its role in the antimicrobial immune responses and complement regulation. Fish Shellfish. Immunol. 2023, 141, 109092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urán Carmona, P.A. Etiology of Soybean-Induced Enteritis in Fish. Ph.D. Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of Fold Change and Dispersion for RNA-Seq Data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.G.; Han, Y.; He, Q.Y. clusterProfiler: An R Package for Comparing Biological Themes Among Gene Clusters. OMICS A J. Integr. Biol. 2012, 16, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, A.B.; Zhang, S.; Dong, S.H.; Zhang, X.X.; Liang, J.H.; Fang, Y.X.; Tan, B.P.; Zhang, W. Effects of indole-3-butyric acid supplementation in diets containing high soybean meal on growth, intestinal inflammation, and intestinal flora of pearl gentian grouper (Epinephelus fuscoguttatus ♀ × Epinephelus lanceolatus ♂). Aquacult. Int. 2024, 32, 4429–4447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, R.; Wu, H.; Guo, R.; Liu, Q.; Pan, L.; Li, J.; Hu, Z.; Chen, C. The diversity of four anti-nutritional factors in common bean. Hortic. Plant J. 2016, 2, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Krogdahl, Å.; Gajardo, K.; Kortner, T.M.; Penn, M.; Gu, M.; Berge, G.M.; Bakke, A.M. Soya saponins induce enteritis in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 3887–3902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Do, M.H.; Lee, E.; Oh, M.J.; Kim, Y.; Park, H.Y. High-glucose or -fructose diet cause changes of the gut microbiota and metabolic disorders in mice without body weight change. Nutrients 2018, 10, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ran, C.; Ding, Q.W.; Liu, H.L.; Xie, M.X.; Yang, Y.L.; Xie, Y.-D.; Gao, C.-C.; Zhang, H.-L.; Zhou, Z.-G. Ability of prebiotic polysaccharides to activate a hif1α-antimicrobial peptide axis determines liver injury risk in zebrafish. Commun. Biol. 2019, 2, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Tao, F.Y.; Dai, Z.R.; Wang, T.C.; Zhang, C.X.; Fang, H.L.; Qin, M.; Qi, C.; Li, Y.; Hao, J.G. Neohesperidin dihydrochalcone can improve intestinal structure and microflora composition of diabetic zebrafish. J. Funct. Foods 2024, 115, 106118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Baker, S.S.; Gill, C.; Liu, W.; Alkhouri, R.; Baker, R.D.; Gill, S.R. Characterization of gut microbiomes in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) patients: A connection between endogenous alcohol and NASH. Hepatology 2013, 57, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.C.; Den, H.; Sun, H.C.; Si, W.T.; Li, X.Y.; Hu, J.; Huang, M.J.; Fan, W.Q. Changes of intestinal microbiota in the giant salamander (Andrias davidianus) during growth based on high-throughput sequencing. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1052824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.R.; Zhang, Z.; Ding, Q.W.; Yang, Y.L.; Bindelle, J.; Ran, C.; Zhou, Z.G. Intestinal Cetobacterium and acetate modify glucose homeostasis via parasympathetic activation in zebrafish. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, A.R.; Meng, D.L.; Hao, Q.; Xia, R.; Zhang, Q.S.; Ran, C.; Yang, Y.Y.L.; Li, D.J.; Liu, W.S.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Effect of supplementation of solid-state fermentation product of Bacillus subtilis HGcc-1 to high-fat diet on growth, hepatic lipid metabolism, epidermal mucus, gut and liver health and gut microbiota of zebrafish. Aquaculture 2022, 560, 738542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhou, W.W.; Shi, D.D.; Pan, F.F.; Sun, W.W.; Yang, P.L.; Li, X.M. The Interaction between Oxidative Stress Biomarkers and Gut Microbiota in the Antioxidant Effects of Extracts from Sonchus brachyotus DC. in Oxazolone-Induced Intestinal Oxidative Stress in Adult Zebrafish. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Xie, M.X.; Xie, Y.D.; Liang, H.; Li, M.; Ran, C.; Zhou, Z.G. Effect of dietary supplementation of Cetobacterium somerae XMX-1 fermentation product on gut and liver health and resistance against bacterial infection of the genetically improved farmed tilapia (GIFT, Oreochromis niloticus). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2022, 124, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, K.J.; Selfors, L.M.; Bui, J.; Reynolds, A.; Leake, D.; Khvorovam, A.; Brugge, J.S. Identification of genes that regulate epithelial cell migration using an siRNA screening approach. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008, 10, 1027–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanabe, T.; Yamada, M.; Noma, T.; Kajii, T.; Nakazawa, A. Tissue-specific and developmentally regulated expression of the genes encoding adenylate kinase isozymes. J. Biochem. 1993, 113, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Huang, G.; Xu, T.; Yin, D.; Bai, J.; Gu, W. Early developmental exposure to pentachlorophenol causes alterations on mRNA expressions of caspase protease family in zebrafish embryos. Chemosphere 2017, 180, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Zhang, S.; Yang, H.; Luo, K.; Wen, J.; Hu, Y.; Hu, R.; Huang, Q.; Cheng, J.; Fu, J. Prognostic significance of gamma-glutamyltransferase in patients with resectable esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Dis. Esophagus 2014, 28, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Ju, J.; Wang, Y.T.; Zhu, Z.; Lu, W.Y.; Zhang, Y.Y. Micro-and nano-plastics induce kidney damage and suppression of innate immune function in zebrafish (Danio rerio) larvae. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 931, 172952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathavarajah, S.; Thompson, A.W.; Stoyek, M.R.; Quinn, T.A.; Roy, S.; Braasch, I.; Dellaire, G. Suppressors of cGAS-STING are downregulated during fin-limb regeneration and aging in aquatic vertebrates. J. Exp. Zool. B Mol. Dev. Evol. 2023, 342, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.L.; Yang, T.L.; Xu, Y.R.; Liang, B.B.; Liu, X.Y.; Cai, Y. Anti-inflammatory and immunoregulatory effects of colistin sulphate on human PBMCs. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2024, 28, e18322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sloin, H.E.; Ruggiero, G.; Rubinstein, A.; Storz, S.S.; Foulkes, N.S.; Gothilf, Y. Interactions between the circadian clock and TGF-β signaling pathway in zebrafish. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0199777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, R.; Ai, Q.; Mai, K.; Xu, W. Effects of conjugated linoleic acid on growth, non-specific immunity, antioxidant capacity, lipid deposition and related gene expression in juvenile large yellow croaker (Larmichthys crocea) fed soyabean oil-based diets. Br. J. Nutr. 2013, 110, 1220–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajri, T.; Pronczuk, A.; Hayes, K.C. Linoleic acid-rich diet increases hepatic taurine and cholesterol 7 alpha-hydroxylase activity in conjunction with altered bile acid composition and conjugation in gerbils. J. Nutr. Biochem. 1998, 9, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleck, A.K.; Hucke, S.; Teipel, F.; Eschborn, M.; Klotz, L. Dietary conjugated linoleic acid links reduced intestinal inflammation to amelioration of CNS autoimmunity. Brain 2021, 144, 1152–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Meng, F.; Piao, F.; Jin, B.; Li, W. Effect of taurine on intestinal microbiota and immune cells in Peyer’s patches of immunosuppressive mice. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1155, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Bao, Y.R.; Wang, S.A.; Li, T.J.; Chang, X.; Yang, G.L.; Meng, X.S. Anti-Inflammation Effects and Potential Mechanism of Saikosaponins by Regulating Nicotinate and Nicotinamide Metabolism and Arachidonic Acid Metabolism. Inflammation 2016, 39, 1453–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Raw Material g/kg | FM | SBM | LE1 | LE2 | LE3 | LE4 | LE5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fish meal | 615 | 615 | 615 | 615 | 615 | 615 | 615 |

| Soyasaponins | 0 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Wheat meal | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 |

| Starch | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 |

| Fish oil | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

| Vitamin mix a | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Mineral mix b | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Cellulose | 10 | 5 | 4.75 | 4.5 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| β,β-Dimethylacrylshikonin | 0 | 0 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| Gross weight (g) | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 |

| Proximate composition (%, dry weight) | |||||||

| Crude protein (%) | 44.63 | 44.58 | 44.66 | 44.61 | 44.59 | 44.58 | 44.62 |

| Crude lipid (%) | 11.03 | 11.02 | 11.05 | 10.98 | 11.04 | 11.03 | 10.99 |

| Gene Name | Forward Primer (5′-3′) | Reverse Primer (5′-3′) | Amplicon (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| il-1β | TGGACTTCGCAGCACAAAATG | GTTCACTTCACGCTCTTGGATG | 150 | Hedrera et al., 2013 [1] |

| il8 | TGTGTTATTGTTTTCCTGGCATTTC | GCGACAGCGTGGATCTACAG | 81 | Hedrera et al., 2013 [1] |

| il10 | CACTGAACGAAAGTTTGCCTTAAC | TGGAAATGCATCTGGCTTTG | 120 | Hedrera et al., 2013 [1] |

| β-actin | GCCAACAGAGAGAAGATGACACAG | CAGGAAGGAAGGCTGGAAGAG | 110 | Hedrera et al., 2013 [1] |

| Gene Name | Forward Primer (5′-3′) | Reverse Primer (5′-3′) | Amplicon (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| amh | TACCGTTCAGTGTTGCTCCT | TTGTTGGCGTTGTTCAGAGG | 226 |

| itln3 | ACGGCACCTACATAAACCCA | CCACAAGAGTCCATCCACCT | 192 |

| daw1 | CGTATGCCTGGCCTTTAACC | GACCAATCGATCACCCGTTG | 166 |

| col9a2 | CCTCCTGGTCTTGATGGTGT | CCGCTTCTTGTAGTCTGGGA | 178 |

| rnasel2 | AAAATTCCTGAGGCAGCACG | GTGACCACAGGAAAAGGCTG | 222 |

| tcnl | GGAAGGCCTGATGTTTGGAG | CGACTCCGCTTTTCTCAGAC | 173 |

| nfil3-3 | TGGAAATGAAGGCGCTGATG | TGAGCTCGGCCACTTCTTTA | 197 |

| β-actin | GCCAACAGAGAGAAGATGACACAG | CAGGAAGGAAGGCTGGAAGAG | 110 |

| Gene Name | Forward Primer (5′-3′) | Reverse Primer (5′-3′) | Amplicon (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ak8 | AGCTGCAACCTATCTCTGGG | TCAGTTGGCGTTTCTGTGTG | 194 |

| casp8l1 | GGAGCCTCTTCAATCCACCT | AAATCGTCCCGCACTTCAAC | 240 |

| epob | TGGACCACTTCGTTCGAGAA | TTGCTGACTGTTTTCCTGGC | 214 |

| nog2 | CGCTACATCAAGGAGGGGAA | GCACTGGGAGATGATGGGAT | 177 |

| cyp2j20 | AACCCTTTGACCCTCGCTTA | GTCCAGGCAGCAATCTCATG | 201 |

| ggt1a | TCTCTTGTTGCTGGGATGGT | CCCTCCCAACCTCAGAACAT | 163 |

| alox5b.2 | CAAAGAGAGAAGCAGCGACC | CCGATAACAGGGGAACTCGA | 223 |

| β-actin | GCCAACAGAGAGAAGATGACACAG | CAGGAAGGAAGGCTGGAAGAG | 110 |

| FM | SBM | LE1 | LE2 | LE3 | LE4 | LE5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBW (g) | 0.241 ± 0.017 | 0.244 ± 0.039 | 0.236 ± 0.030 | 0.252 ± 0.035 | 0.251 ± 0.008 | 0.238 ± 0.018 | 0.236 ± 0.036 |

| WGR (%) | 17.964 ± 0.743 | 14.841 ± 2.620 | 14.954 ± 1.842 | 15.358 ± 2.112 | 14.989 ± 1.768 | 17.067 ± 1.846 | 14.869 ± 1.648 |

| SGR (%) | 1.180 ± 0.090 a | 0.988 ± 0.021 b | 0.995 ± 0.008 b | 1.021 ± 0.023 ab | 0.998 ± 0.011 b | 1.126 ± 0.100 a | 0.990 ± 0.092 b |

| SR (%) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, M.; Lu, X.; Lim, L.-S.; Peng, Y.; Liu, L.; Tan, K.; Xu, P.; Liang, M.; Wu, Y.; Gong, Q.; et al. β,β-Dimethylacrylshikonin Alleviates Zebrafish (Danio rerio) Soyasaponin-Induced Enteritis by Maintaining Intestinal Homeostasis and Improving Intestinal Immunity and Metabolism. Fishes 2025, 10, 567. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10110567

Liu M, Lu X, Lim L-S, Peng Y, Liu L, Tan K, Xu P, Liang M, Wu Y, Gong Q, et al. β,β-Dimethylacrylshikonin Alleviates Zebrafish (Danio rerio) Soyasaponin-Induced Enteritis by Maintaining Intestinal Homeostasis and Improving Intestinal Immunity and Metabolism. Fishes. 2025; 10(11):567. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10110567

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Ming, Xin Lu, Leong-Seng Lim, Yinhui Peng, Lulu Liu, Kianann Tan, Peng Xu, Mingzhong Liang, Yingrui Wu, Qingfang Gong, and et al. 2025. "β,β-Dimethylacrylshikonin Alleviates Zebrafish (Danio rerio) Soyasaponin-Induced Enteritis by Maintaining Intestinal Homeostasis and Improving Intestinal Immunity and Metabolism" Fishes 10, no. 11: 567. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10110567

APA StyleLiu, M., Lu, X., Lim, L.-S., Peng, Y., Liu, L., Tan, K., Xu, P., Liang, M., Wu, Y., Gong, Q., & Cai, X. (2025). β,β-Dimethylacrylshikonin Alleviates Zebrafish (Danio rerio) Soyasaponin-Induced Enteritis by Maintaining Intestinal Homeostasis and Improving Intestinal Immunity and Metabolism. Fishes, 10(11), 567. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10110567