Comparing Knowledge: An Analysis of the Relative Epistemic Powers of Groups

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Group Epistemic Logic: Distributed, Common, and Comparative Knowledge

2.1. Syntax and Semantics

- Vocabulary: agents, groups, and atoms. Throughout this paper, we assume a fixed (finite) set of agents, and a set of atomic sentences. We use capital letters to denote groups of agents, i.e., non-empty subsets of .

- Syntax. The language of the logic of Distributed knowledge, Common knowledge, and Epistemic Group Comparisons is recursively defined by the following BNF form:

- Here, atoms p denote ontic “facts” (of a non-epistemic nature); ¬ and ∧ are classical negation and conjunction; says that is group (distributed) knowledge in the group of agents ; says that is common knowledge in the group A; while is an epistemic comparison statement, saying that group A’s distributed knowledge includes group B’s distributed knowledge. In general, when we refer to a group’s “knowledge”, we will mean the group’s distributed knowledge. So can be read as short for “group A knows at least as much as group B” (or group A knows all B knows). Note that for groups consisting of single agents, we will skip the brackets and write instead of . Note that individual knowledge is not a primitive notion in this language: it will be defined as the distributed knowledge of the singleton-agent group .

- Abbreviations. We have the usual Boolean notions of disjunction , implication , and bi-conditional , and in addition, we adopt the following abbreviations (where is itself an abbreviation for ):

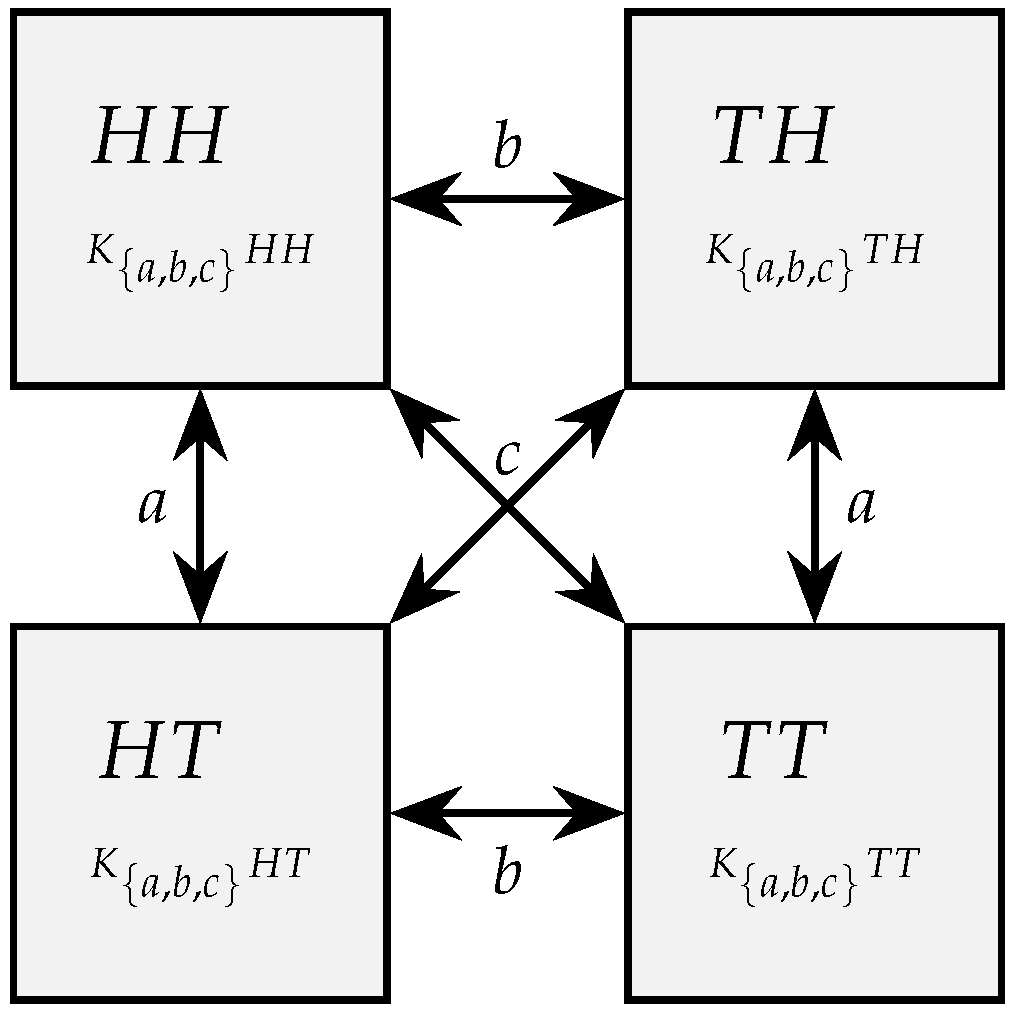

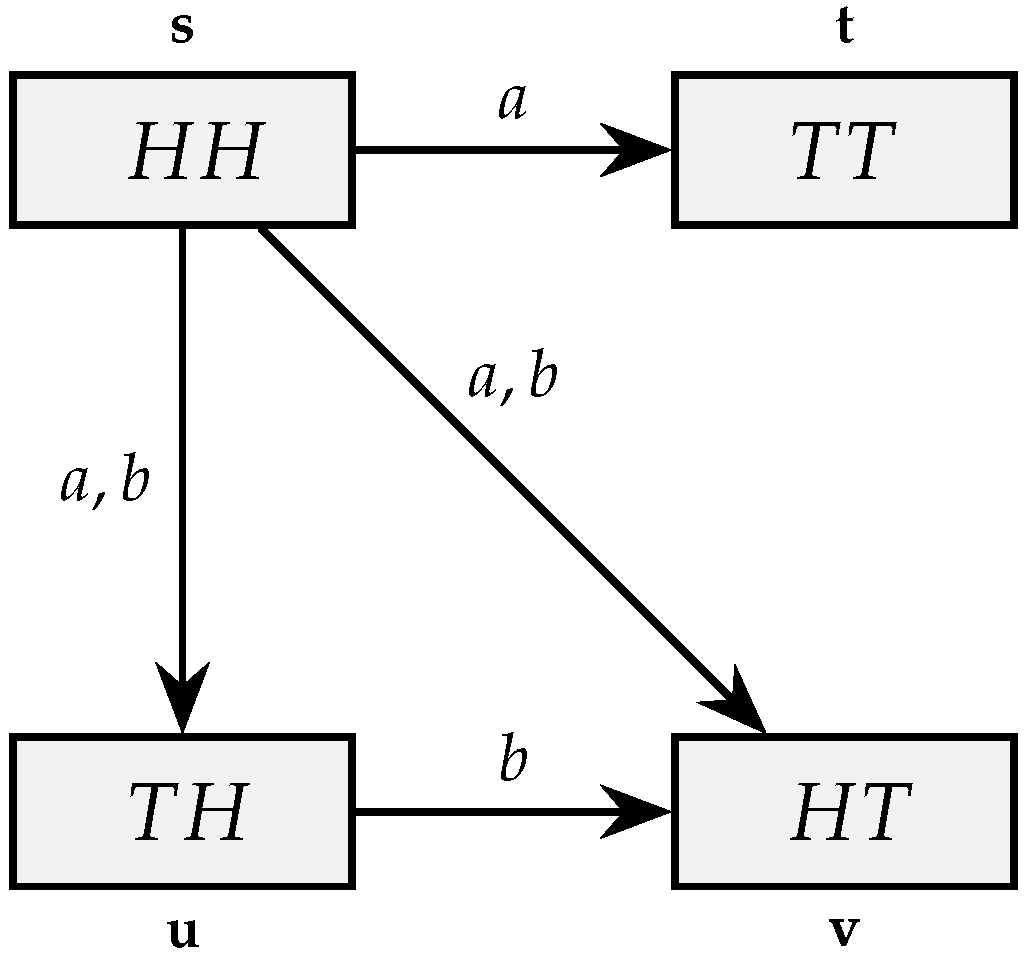

- Epistemic () models. An epistemic model (also called a -model) is just a reflexive multi-agent Kripke model (see [6]); i.e., a relational structure , where

- S is, as usual, a set of possible worlds;

- for each agent , is a reflexive accessibility relation, denoting epistemic possibility: means intuitively that world w is consistent with agent a’s knowledge in world s (hence, w is a “possible” alternative for s from a’s perspective);

- the valuation or truth-assignment function, , maps every element of the given set of atomic sentences into sets of possible worlds. Intuitively, for every given atomic sentence , the valuation tells us in which worlds the factual content of p is true.

- The fact that we require to be reflexive corresponds to the assumption of Veracity of Knowledge (i.e., knowledge implies truth: ), also known as the axiom T in Modal Logic.

- models. An epistemic model is an model if all accessibility relations are preorders (i.e., not only reflexive, but also transitive). Requiring to be transitive corresponds to the assumption of Positive Introspection (i.e., knowledge implies knowledge of knowledge: ), also known as the KK Principle in Epistemology, or axiom 4 in Modal Logic.

- models. Finally, an epistemic model is an model if all accessibility relations are equivalence relations (i.e., reflexive, symmetric, and transitive). In the context of the other two conditions, symmetry of is equivalent to another relational property, called Euclideaness, which corresponds to the assumption of Negative Introspection (i.e., ignorance implies knowledge of ignorance: ), also known as the axiom 5 in Modal Logic.

- Joint possibility and common-knowledge possibility relations. To define notions of group knowledge, we need to extend our accessibility relations to groups of agents . The joint possibility relation is defined as the intersection of the individual accessibility relations for the agents in the group A, i.e.,

- Semantics. Given any epistemic model , we can define the satisfaction relation (between worlds w in M and formulas ); and when the model is fixed, we skip the subscript and simply write . The definition is by recursion on the complexity of formulas , via the following clauses:

- In words: the semantics of atoms is given by the valuation; the semantics of Boolean connectives is classical; and are defined as standard Kripke modalities for the relations and ; finally, holds iff group A (distributedly) knows all that group B (distributedly) knows (or equivalently: every world accessed by group A’s joint possibility relation is also accessed by group B’s joint possibility relation).

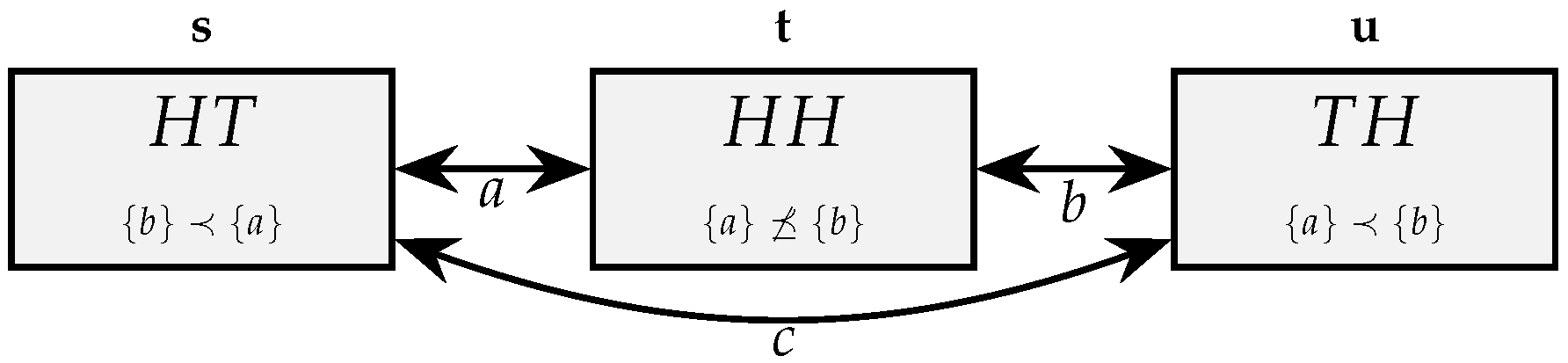

- Validity (, , or ). We can define a notion of validity for each of our three classes of epistemic models: we say that is -valid, and write , if is true in all possible worlds in all -models; similarly, we define -validity , and -validity .Note that the strict version of the epistemic comparison operator expresses that (locally, in the actual world) group A is “more expert” than (or “epistemically superior” to) group B. The epistemic equivalence statement says that the epistemic positions of B and C are equally strong (in the actual world). Finally, means that the two groups are epistemically incomparable: none of them is superior, but they are not equally strong either. This leads to the following observation:

2.2. Axiomatisation of

3. Reasoning About Epistemic Comparison

3.1. Knowledge, Distributed Knowledge, and Common Knowledge About Epistemic Comparison in Models

- To prove the second statement, we use the theorem in which states that whenever is provable then so is , together with the proof of the first statement in this proposition. □

- To prove the second item, we use the valid equivalence . In case then Proposition 3 shows that does follow, hence the only option that remains is . To show that it does not imply , we refer back to the proof of the first statement in this observation. □

- Common Knowledge about Epistemic Comparison.4 If it happens to be the case that a less-expert agent does know that another agent knows at least as much, then this fact is common knowledge among the group of both agents in (and ) models.

3.2. Reasoning About Overlapping Groups and Epistemic Free-Riders

- Overlapping Groups. We consider the case in which two groups, and , overlap only in A, i.e., they have a subgroup of agents A in common. For example, we can think of scenarios in which A are the “double-spy agents” belonging to two competing teams. As one may expect, the double-agents A may play a crucial role in establishing one team’s epistemic position with respect to another team. More specifically, the competitive epistemic advantage of a group over in the presence of the double agents A, does not imply that the group B necessarily will have the same epistemic advantage over C without A, as it may well be the case that B and C are themselves epistemically equal or incomparable. The latter case is expressed in the following observation:

- Epistemic free-riders. Given a state of comparative knowledge of a large group C consisting of different sub-groups, we can analyze the relative contribution of any of its subgroups to the knowledge of the overall larger group C. For instance, if C is split into two disjoint subgroups, A and B (i.e., with ), then means that, in principle, B makes no additional contribution over A to the bigger group C and can be seen as an “epistemic free-rider”. Here, B does not contribute anything new that is not already “known” by A. In these cases when only the knowledge of the group is at stake, the group C will not gain any added epistemic value by consulting B as long as A’s knowledge is available to C. In contrast, when the groups A and B are epistemically equivalent, i.e., , one of the two groups A or B already covers all the knowledge of the other group, so either one of them can be an epistemic free-rider, but not both, as at least one of them will need to keep its position within C.

3.3. “Known Superiority” Revisited

4. Conclusions

- Common distributed knowledge. Given a family of groups of agents, we say that is common distributed knowledge among (the groups in) the supergroup , if we have that: each group has distributed knowledge that ; each group has distributed knowledge that each other group has distributed knowledge that ; etc. (for all iterations). Formally:

- The proofs of these generalized statements for common distributed knowledge in the case make use of the valid axioms for common distributed knowledge provided in [8]; while for we drop the negative introspection axiom for common distributed knowledge. This opens the door to further studies on what a supergroup commonly can know about its own relative epistemic power.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | As our epistemic relations are already reflexive, this is the same as the transitive closure. |

| 2 | This is a variation of the example in [9], which uses a penny–quarter box to illustrate the logical properties of a classical physical system. |

| 3 | |

| 4 | The propositions with epistemic comparison in this section that involve common knowledge are restricted to comparison statements between singleton groups of agents. A generalization to epistemic comparison statements between arbitrary groups of agents can be obtained but requires the use of the notion of common distributed knowledge. We comment on this in the conclusion of this paper. |

| 5 | The concept was first defined (but not axiomatized) in the master’s thesis [21] supervised by A. Baltag, and was independently discussed in [22,23]. In [8], a sound and complete axiomatization for the logic of common distributed knowledge with epistemic comparison is provided and it is shown to be decidable. In the context of dynamic epistemic logic (DEL), the concept is further studied in [8,11,24] and continues the earlier line of work on converting distributed knowledge into common knowledge (see [25] and [26]). |

References

- Fagin, R.; Halpern, J.; Moses, Y.; Vardi, M. Reasoning About Knowledge; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- van Benthem, J. Information as Correlation Versus Information as Range; Technical Report PP-2006-07; University of Amsterdam: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Halpern, J.; Moses, Y. Knowledge and common knowledge in a distributed environment. In Proceedings of the Third Annual ACM Symposium on Principles of Distributed Computing, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 27–29 August 1984; pp. 50–61. [Google Scholar]

- Vanderschraaf, P.; Sillari, G. Common Knowledge. In Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, J.; Sato, M.; Hayashi, T.; Igarishi, S. On the Model Theory of Knowledge; Technical Report STAN-CS-78-657; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn, P.; de Rijke, M.; Venema, Y. Modal Logic; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Van Ditmarsch, H.; van der Hoek, W.; Kooi, B. Knowing More: From Global to Local Correspondence. In Proceedings of the 21st International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Pasadena, CA, USA, 11–17 July 2009; pp. 955–960. [Google Scholar]

- Baltag, A.; Smets, S. Learning what others know. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Logic for Programming AI and Reasoning, Alicante, Spain, 22–27 May 2020; EPiC Series in Computing. Kovacs, L., Albert, E., Eds.; Volume 73, pp. 90–110. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, R.I.G. Quantum Logic. Sci. Am. 1981, 245, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltag, A.; van Benthem, J. A Simple Logic of Functional Dependence. J. Philos. Log. 2021, 50, 939–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltag, A.; Smets, S. Logics for Data Exchange and Communication. In AiML Proceedings, Advances in Modal Logic; College Publications: Rickmansworth, UK, 2024; Volume 15, pp. 147–170. [Google Scholar]

- Baltag, A.; Moss, L.; Solecki, S. The Logic of Public Announcements, Common Knowledge, and Private Suspicions. In Proceedings of the 7th Conference on Theoretical Aspects of Rationality and Knowledge (TARK-98), Evanston, IL, USA, 22–24 July 1998; pp. 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Baltag, A.; Renne, B. Dynamic Epistemic Logic. In Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- van Benthem, J. Logical Dynamics of Information and Interaction; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- van Ditmarsch, H.; van der Hoek, W.; Kooi, B. Dynamic Epistemic Logic; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Baltag, A.; Bezhanishvili, N.; Ozgün, A.; Smets, S. Justified Belief, Knowledge, and the Topology of Evidence. Synthese 2022, 200, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltag, A.; Christoff, Z.; Hansen, J.U.; Smets, S. Logical models of informational cascades. In Logic Across the University: Foundations and Applications: Proceedings of the Tsinghua Logic Conference; van Benthem, J., Liu, F., Eds.; College Publications: Rickmansworth, UK, 2013; Volume 47, pp. 405–432. [Google Scholar]

- Baltag, A.; Christoff, Z.; Rendsvig, R.K.; Smets, S. Dynamic Epistemic Logics of Diffusion and Prediction in Social Networks. Stud. Log. 2019, 107, 489–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smets, S.; Velazquez-Quesada, F. A Logical Analysis of the Interplay Between Social Influence and Friendship Selection. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Dynamic Logic. New Trends and Applications: Second International Workshop, DaLí 2019, Porto, Portugal, 7–11 October 2019; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Volume 12005, pp. 71–87. [Google Scholar]

- Baltag, A.; Smets, S. A Qualitative Theory of Dynamic Interactive Belief Revision. In Logic and the Foundations of Game and Decision Theory (LOFT 7), Texts in Logic and Games; Bonanno, G., van der Hoek, W., Wooldridge, M., Eds.; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; Volume 3, pp. 13–60. [Google Scholar]

- van Wijk, S. Coalitions in Epistemic Planning. Master’s Thesis, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. Available online: https://www.illc.uva.nl/Research/Publications/Reports/MoL/ (accessed on 3 September 2015).

- Seligman, J.; University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand. The Logic of Hacking. Research Paper. unpublished manuscript. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, J. Varieties of Group Knowledge, Presentation Slides. Available online: https://logicicworkshop2015.wordpress.com/presentation-articles-more/ (accessed on 1 December 2015).

- Baltag, A.; Smets, S. Group Knowledge of Hypothetical Values. In Proceedings of the TARK Proceedings Twentieth Conference on Theoretical Aspects of Rationality and Knowledge, Düsseldorf, Germany, 14–16 July 2025; pp. 140–159. [Google Scholar]

- van Benthem, J. One is a lonely number. In Logic Colloquium; Koepke, P., Chatzidakis, Z., Pohlers, W., Eds.; ASL and A.K. Peters: Wellesley, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 96–129. [Google Scholar]

- Baltag, A.; Smets, S. Protocols for Belief Merge: Reaching Agreement via Communication. Log. J. Igpl. 2013, 21, 468–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (I) | Axioms and rules of classical propositional logic |

|---|---|

| (II) | axioms and rules for distributed knowledge: |

| (-Necessitation) | From , infer |

| (-Distribution) | |

| (Veracity) | |

| (III) | Axioms for comparative knowledge: |

| (Inclusion) | , provided that |

| (Additivity) | |

| (Transitivity) | |

| (Knowledge Transfer) | |

| (IV) | Axioms and rules for common knowledge: |

| (-Necessitation) | From , infer |

| (-Distribution) | |

| (-Fixed Point) | |

| (-Induction) | |

| (V) | Special axioms for -models: |

| (Positive Introspection) | |

| (VI) | Special axioms for -models: |

| (Negative Introspection) | |

| (Known Superiority) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baltag, A.; Smets, S. Comparing Knowledge: An Analysis of the Relative Epistemic Powers of Groups. Philosophies 2025, 10, 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies10060136

Baltag A, Smets S. Comparing Knowledge: An Analysis of the Relative Epistemic Powers of Groups. Philosophies. 2025; 10(6):136. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies10060136

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaltag, Alexandru, and Sonja Smets. 2025. "Comparing Knowledge: An Analysis of the Relative Epistemic Powers of Groups" Philosophies 10, no. 6: 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies10060136

APA StyleBaltag, A., & Smets, S. (2025). Comparing Knowledge: An Analysis of the Relative Epistemic Powers of Groups. Philosophies, 10(6), 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies10060136