Integrating Morality and Science: Semi-Imperative Evidentialism Paradigm for an Ethical Medical Practice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

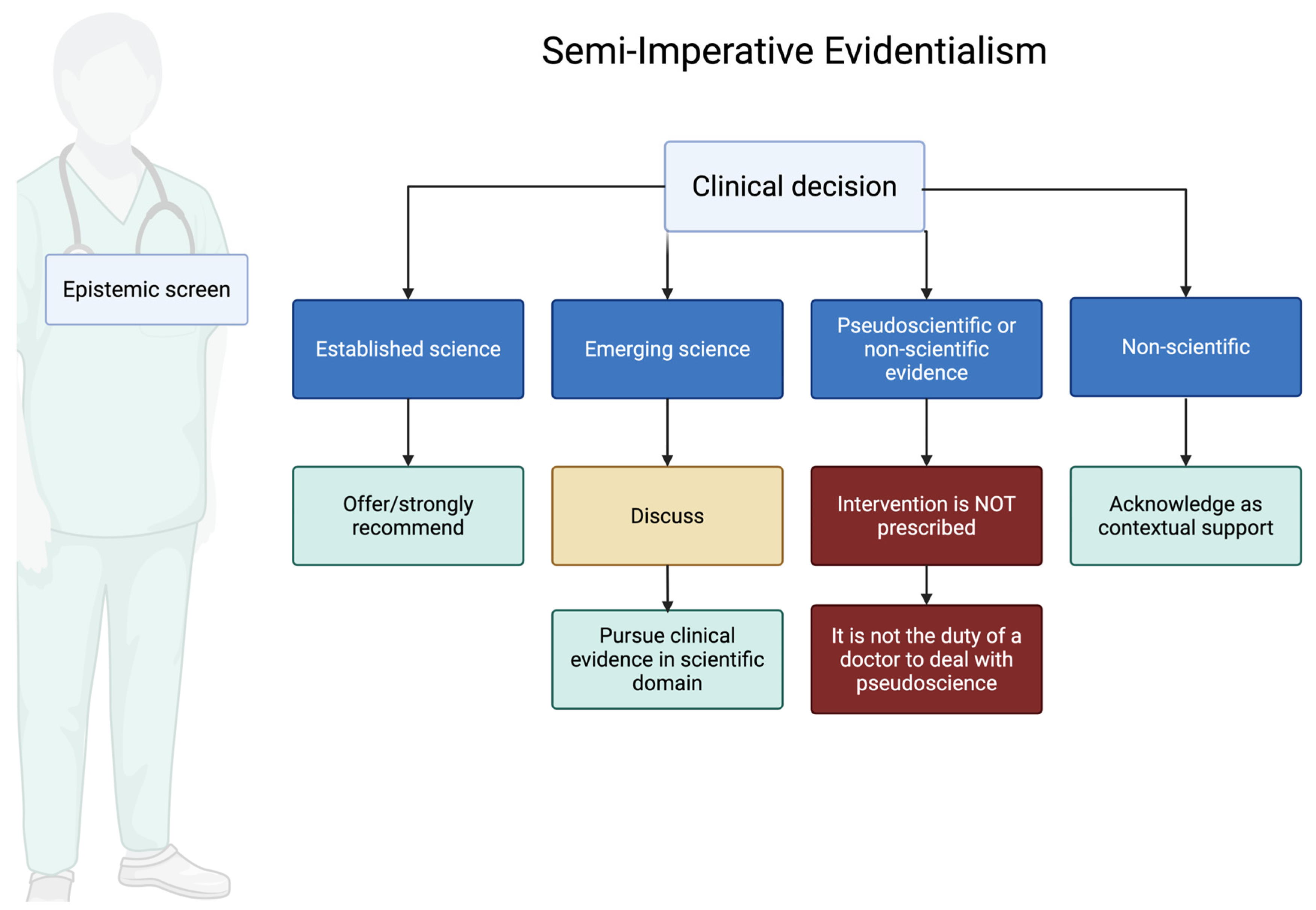

- Science: We treat an activity as scientific when it advances testable, potentially falsifiable claims about disease mechanisms or outcomes and subjects those claims to disciplined methods (controls, transparency, error-checking, and communal critical scrutiny). The relevant question is not whether a phenomenon is “quantifiable” in the abstract, but whether the methods invite empirical risk and possible correction. It relates to concepts or treatments that can be empirically verified and tested through rigorous scientific methodologies. In the field of medicine, a therapy is considered scientific if it has been subjected to rigorous peer-reviewed research and controlled, repeatable experiments that provide significant evidence of its effectiveness and safety. Disciplines such as psychology and behavioral medicine are classified as Science when they offer testable hypotheses and falsifiable predictions. Within Science, SIE distinguishes two evidence tiers used for ethical duties at the bedside:

- 1.1

- Tier 1: Clinical science: Clinical studies, such as randomized clinical trials (RCTs) for therapies or meticulously executed case–control studies with minimal biases for diagnostic tests, exemplify this field of medical science. Clinical science is the fundamental basis of EBM. Tier 1 comprises high-certainty clinical evidence (e.g., randomized clinical trials for therapies, well-designed diagnostic accuracy studies); clinicians have a strong duty to offer or strongly recommend to eligible patients and to communicate benefits and harms.

- 1.2

- Tier 2: Pre-Clinical Science: On the other hand, pre-clinical science explores the foundational understanding of biological processes, substances, and surrogate outcomes. This course focuses on the theoretical foundations and possible therapeutic implications of novel findings occurring at the level of cells, molecules, or genes. Although pre-clinical science contributes significantly to the development of medical knowledge and creates a foundation for future clinical applications, it cannot epistemologically determine the efficacy of clinical therapies. Its applicability is limited to scholarly journals and laboratory settings where it acts as a catalyst for further clinical studies. It is inappropriate and potentially deceptive to rely solely on pre-clinical science in daily clinical practice since it has not been subjected to exhaustive tests necessary to verify its safety and efficacy in human subjects. A duty to discuss the intervention with patients, clearly disclosing the uncertainty surrounding its efficacy and/or safety. If offered, it should ideally be within a research or trial setting, or with explicit acknowledgment of its investigational nature and with robust informed consent. The potential benefits must be carefully weighed against the uncertainties and potential risks.

- Pseudoscience: falsified information masquerading as scientific knowledge. Despite the lack of empirical support and methodological rigor of science, it often asserts its scientific legitimacy and authority. Pseudoscientific therapies may be measurable or observable, but they claim that they do not fall within the scope of scientific investigation, or that they manipulate scientific language and evidence in such a way as to mislead or confuse. This is particularly detrimental due to the risk of harm to patients, waste of resources and a decline in confidence in legitimate medical practices. Pseudoscience is considered to be ethically problematic from the point of view of the SIE, since it undermines the commitment to evidence-based practice and logical decision-making. A clear ethical duty to refuse to offer or endorse the intervention and to educate the patient about the lack of credible evidence, potential harms (including opportunity costs), and the distinction between evidence-based approaches and pseudoscience.

- Non-science: This category is distinct. It does not refer to interventions proposed as alternatives to scientific treatments for specific conditions, but rather to aspects of care that address the patient’s broader context, such as psychological, spiritual, social, economic, and cultural factors. These are not subject to the same tiering as interventions but are integral to ethical medical practice. A distinct ethical duty exists to address non-scientific aspects relevant to patient well-being. As the General Medical Council (GMC) stipulates, doctors must “adequately assess a patient’s condition(s), taking account of their history including relevant psychological, spiritual, social, economic, and cultural factors” [12]. Furthermore, in contexts like palliative care, the GMC highlights the doctor’s role in “providing psychological, social and spiritual support to patients; and supporting those close to the patient” [13]. SIE emphasizes that these non-scientific elements are crucial for holistic care and patient-centeredness. The ethical duty here is to acknowledge, explore, and appropriately integrate these factors into the overall care plan, ensuring they do not conflict with or falsely substitute for evidence-based interventions for medical conditions. This delineates the use of non-science in the broader context of patient care from the evaluation of specific non-scientific interventions proposed for medical efficacy (which would likely be classified as pseudoscience or lacking evidence if making medical claims without a scientific basis). Classifying a ritual, belief, or lifestyle practice as Non-science is not a pejorative verdict. It simply acknowledges that the activity’s primary purpose is existential support rather than measurable biomedical effect. SIE encourages clinicians to honor—and, when appropriate, actively facilitate—patients’ spiritual, cultural, or personal traditions so long as they do not claim to cure disease or displace evidence-based care. In this way the framework safeguards both scientific integrity and the patient’s right to pursue sources of meaning that enhance coping, resilience, and well-being.

3. Results

3.1. Operationalizing the Three Epistemic Domains

| Attribute (Yes/No) | Science (S) | Pseudoscience (PS) | Non-Science (NS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Empirical claim of physiologic efficacy (disease-specific) | Yes | Yes | No |

| 2. Falsifiable mechanism/testable prediction | Yes | No (or ad hoc excuses) | N/A |

| 3. Compatible with well-established scientific laws | Yes | Often violates or ignores | N/A |

| 4. Evidence base currently available | Tier 1/2 data (see Figure 1) | Low-quality, contradictory, or none | Not applicable |

| 5. Intended as substitute for standard therapy | Possibly | Typically promoted as substitute | Never |

| 6. Primary purpose (therapeutic vs. meaning-making) | Treat/prevent pathology | Treat/prevent pathology | Meaning, identity, community |

3.2. The SIE Tier and Patient Discretion Matrix

3.3. Application of SIE to Clinical Reversals

- The Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST)—Flecainide [25]:

- −

- Initial Situation: Flecainide and similar antiarrhythmic drugs were widely used post-myocardial infarction (MI) to suppress ventricular premature depolarizations (a surrogate outcome), based on the plausible pathophysiological theory that suppressing these arrhythmias would reduce mortality.

- −

- SIE Application: Initially, this practice might have been classified as Tier 2 (strong theoretical basis, some observational support for surrogate outcome). However, SIE requires continuous vigilance for higher-quality evidence on hard clinical endpoints (e.g., all-cause mortality) and explicitly discounts surrogate-only rationales.

- −

- Reversal: The CAST trial, a Tier 1 RCT, revealed that flecainide and encainide increased mortality despite effectively suppressing arrhythmias [25].

- −

- SIE’s Earlier Re-classification: Under SIE, the CAST findings trigger immediate downgrading from Tier 2 to “contraindicated for this indication,” with a professional duty to cease prescribing, document the rationale, and educate peers and patients about the reversal. The framework’s periodic re-calibration mechanism would ensure such pivotal evidence leads to immediate practice change.

3.4. Navigating Ethical Dilemmas with SIE: Special Access Programs and CAM

- −

- SIE Application: When early signals exist but confirmatory trials are negative or equivocal, SIE mandates re-scoring to “do not offer outside a trial,” paired with a duty to educate about the evidentiary trajectory and the risks of diverting patients from proven care.

- −

- SIE Application: SIE’s Pseudoscience tier directly addresses many CAM practices. It imposes an ethical duty on clinicians to refuse to offer interventions lacking a credible scientific basis or those contradicted by robust evidence. Crucially, this duty is paired with an obligation to educate patients about the lack of evidence, potential harms of abandoning proven therapies, and the distinction between evidence-based approaches and pseudoscience. This empowers patients to make informed choices rather than decisions based on misinformation or unsubstantiated claims.

4. Discussion: SIE as a Scientific Moral Rule

4.1. SIE and the Philosophy of Medicine

- Reconcile the “Art” and “Science” of Medicine: While firmly anchored in scientific evidence, SIE clarifies that individualized care remains indispensable: clinical recommendations are evidence-constrained but value-informed, integrating patient goals, comorbidity profiles, and context. In SIE, the “art” is not license to deviate from evidence but the disciplined application of Tier-linked duties—offer (Tier 1), conditional offer with explicit consent (Tier 2), and refusal with education (PS)—to the particulars of a patient’s situation.

- Provide a normative bridge from evidence to action: SIE is prescriptive, but it does not infer duties from data alone. It joins a fallibilist epistemology (all claims remain defeasible) to a bridge principle that mediates the is–ought step: when the relevant community of inquiry (clinicians and scientists using transparent, reproducible methods) establishes robust warrant for a clinical claim, physicians incur a pro tanto duty to offer it because this best serves medicine’s fiduciary ends—beneficence, nonmaleficence, and respect for autonomy. By robust warrant we mean high- or moderate-certainty evidence on patient-important outcomes (not surrogates alone), typically from replicated RCT or convergent methods with coherent mechanisms and an acceptable risk–benefit profile. The duty is pro tanto—overridable by contraindications or informed refusal. Accordingly: for Tier 1 (Established Science), clinicians should offer/strongly recommend and document reasons if declined; for Tier 2 (Emerging Science), uncertainty shifts the duty to shared decision-making under explicit consent, preferably within a trial or registry; for Pseudoscience (PS), clinicians should refuse or discontinue, correct misinformation, and redirect to evidence-based options; for Non-science (NS), clinicians may acknowledge and support practices as contextual care when safe and non-substitutive. All classifications are rescorable as new evidence emerges.

- Challenge reductionist views of EBM: SIE guards against algorithmic reductionism by requiring transparency about uncertainty, documentation of informed refusal when Tier-1 care is declined, and periodic re-verification of standards through living syntheses and post-marketing surveillance. Thus, the framework operationalizes “evidence-based” as an ongoing, auditable practice rather than a static checklist.

4.2. Limitations of the Proposal

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sackett, D.; Haynes, B.; Marshall, T.; Morgan, W.K.C. Evidence-based medicine. Lancet 1995, 346, 1171–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sackett, D.L.; Rosenberg, W.M.C.; Gray, J.A.M.; Haynes, R.B.; Richardson, W.S. Evidence based medicine: What it is and what it isn’t. BMJ 1996, 312, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Guerrero, I.M.; Torralbo, M.; Fernández-Cano, A. A forerunner of qualitative health research: Risueno’s report against the use of statistics. Qual. Health Res. 2014, 24, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, M. Epistemological reflections on the art of medicine and narrative medicine. Perspect. Biol. Med. 2008, 51, 406–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huddle, T.S. Our Present Complaint: American Medicine Then and Now. J. Hist. Med. Allied Sci. 2009, 64, 388–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, C.E. Our Present Complaint: American Medicine, Then and Now; JHU Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, A.; Bentley, P.; Polychronis, A.; Grey, J. Evidence-based medicine: Why all the fuss? This is why. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 1997, 3, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, J.S. Evidence-based medicine: A Kuhnian perspective of a transvestite non-theory. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 1998, 4, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, J.N. Evidence-based medicine. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 1997, 3, 149–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polychronis, A.; Miles, A.; Bentley, P. Evidence-based medicine: Reference? Dogma? Neologism? New orthodoxy? J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 1996, 2, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, V.; Cifu, A. A medical burden of proof: Towards a new ethic. BioSocieties 2012, 7, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Medical Council. Decision Making and Consent; GMC: London, UK, 2020; Available online: https://www.gmc-uk.org/professional-standards/the-professional-standards/decision-making-and-consent (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Treatment and Care Towards the End of Life: Good Practice in Decision Making. Available online: https://www.gmc-uk.org/professional-standards/the-professional-standards/treatment-and-care-towards-the-end-of-life (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Fleming, T.R.; DeMets, D.L. Surrogate end points in clinical trials: Are we being misled? Ann. Intern. Med. 1996, 125, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.; Cureton, A. Kant’s Moral Philosophy. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Fall 2024; Zalta, E.N., Nodelman, U., Eds.; Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Popper, K.R. The Logic of Scientific Discovery; Basic Books: Oxford, UK, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Lakatos, I. The Methodology of Scientific Research Programmes: Volume 1: Philosophical Papers; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Thagard, P.R. Why Astrology is a Pseudoscience. PSA Proc. Bienn. Meet. Philos. Sci. Assoc. 1978, 1978, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigliucci, M. Nonsense on Stilts: How to Tell Science from Bunk; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hansson, S.O. Science and Pseudo-Science. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Fall 2025; Zalta, E.N., Nodelman, U., Eds.; Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lakatos, I. Falsification and the Methodology of Scientific Research Programmes. In Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge, Proceedings of the International Colloquium in the Philosophy of Science, London, UK, 11–17 July 1965; Musgrave, A., Lakatos, I., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1970; Volume 4, pp. 91–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, S.O. Defining Pseudo-Science. Philos. Nat. 1996, 33, 169–176. [Google Scholar]

- Pigliucci, M.; Boudry, M. (Eds.) Philosophy of Pseudoscience: Reconsidering the Demarcation Problem; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, V.; Cifu, A.; Ioannidis, J.P.A. Reversals of Established Medical Practices: Evidence to Abandon Ship. JAMA 2012, 307, 37–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruskin, J.N. The cardiac arrhythmia suppression trial (CAST). N. Engl. J. Med. 1989, 321, 386–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, M.J.; Rogers, W.A.; Entwistle, V. Ethical justifications for access to unapproved medical interventions: An argument for (limited) patient obligations. Am. J. Bioeth. 2014, 14, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, E. Unapproved drug use: Compassionate or cause for concern? Lancet Neurol. 2009, 8, 136–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reis, G.; Silva, E.A.; Silva, D.C.; Thabane, L.; Milagres, A.C.; Ferreira, T.S.; dos Santos, C.V.; Campos, V.H.; Nogueira, A.M.; de Almeida, A.P.; et al. Effect of Early Treatment with Ivermectin among Patients with COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1721–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naggie, S.; Boulware, D.R.; Lindsell, C.J.; Stewart, T.G.; Slandzicki, A.J.; Lim, S.C.; Cohen, J.; Kavtaradze, D.; Amon, A.P.; Gabriel, A.; et al. Effect of Higher-Dose Ivermectin for 6 Days vs Placebo on Time to Sustained Recovery in Outpatients with COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2023, 329, 888–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcolino, M.S.; Meira, K.C.; Guimarães, N.S.; Motta, P.P.; Chagas, V.S.; Kelles, S.M.B.; de Sá, L.C.; Valacio, R.A.; Ziegelmann, P.K. Systematic review and meta-analysis of ivermectin for treatment of COVID-19: Evidence beyond the hype. BMC Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Complementary, Alternative, or Integrative Health: What’s in a Name? NCCIH: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/complementary-alternative-or-integrative-health-whats-in-a-name (accessed on 31 December 2023).

- Briggs, J.P.; Killen, J. Perspectives on Complementary and Alternative Medicine Research. JAMA 2013, 310, 691–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werneke, U.; Earl, J.; Seydel, C.; Horn, O.; Crichton, P.; Fannon, D. Potential health risks of complementary alternative medicines in cancer patients. Br. J. Cancer 2004, 90, 408–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.B.; Park, H.S.; Gross, C.P.; Yu, J.B. Use of Alternative Medicine for Cancer and Its Impact on Survival. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2018, 110, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Kim, K.S.; Park, J.H.; Shin, J.-Y.; Kim, S.K.; Park, J.H.; Park, E.C.; Seo, H.G. Factors associated with discontinuation of complementary and alternative medicine among Korean cancer patients. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2013, 14, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, D.; Gadd, B.; Kerridge, I.; Komesaroff, P.A. A gentle ethical defence of homeopathy. J. Bioeth. Inq. 2015, 12, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bilgin, A.; Doner, A.; Erdogan Yuce, G.; Muz, G. The Effect of Biopsychosocial-Spiritual Factors on Medication Adherence in Chronic Diseases in Türkiye. J. Relig. Health 2025, 64, 3853–3873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchetti, G.; Koenig, H.G.; Lucchetti, A.L.G. Spirituality, religiousness, and mental health: A review of the current scientific evidence. World J. Clin. Cases 2021, 9, 7620–7631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capuano, A.M.; Killu, K. Understanding and addressing pseudoscientific practices in the treatment of neurodevelopmental disorders: Considerations for applied behavior analysis practitioners. Behav. Interv. 2021, 36, 242–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, E.D. Character, virtue and self-interest in the ethics of the professions. J. Contemp. Health Law Policy 1989, 5, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nunes, R. Ensaios em Bioética, 1st ed.; Conselho Federal de Medicina: Brasília, Brazil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Laudan, L. The Demise of the Demarcation Problem. In Physics, Philosophy and Psychoanalysis; Cohen, R.S., Laudan, L., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1983; Volume 76, pp. 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, H.G. Religion, spirituality, and health: The research and clinical implications. ISRN Psychiatry 2012, 2012, 278730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Evidence Tier | Physician Duty | Patient Discretion | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Established Science (Tier 1)—high-certainty RCTs/definitive evidence | There is a strong ethical duty to offer or strongly recommend the intervention and to document reasons if not followed. | May refuse with documented acknowledgment | Statins post-myocardial infarction |

| Emerging Pre-clinical Science (Tier 2)—promising but uncertain evidence (early-phase trials, robust observational data, strong biologic plausibility) | Clinicians have a duty to discuss openly, emphasize uncertainty, and preferably deliver within research or registry settings; explicit consent is required. | Shared decision-making. Acceptance usually requires signed acknowledgment or trial consent. | Phase II CRISPR-based gene therapy; prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening |

| Pseudoscience (PS)—biomedical claims that contradict established knowledge or lack any credible empirical support | Clinicians have a clear duty to refuse or discontinue the intervention, to explain the lack of evidence and potential harms (including opportunity cost), and to redirect to evidence-based alternatives. | May pursue independently and at own cost after documented counselling; physician should not facilitate. | High-dose vitamin C infusions for Stage IV cancer |

| Non-science (NS)—spiritual, cultural or social practices not offered as biomedical treatments | Clinicians have a supportive duty to acknowledge and, when compatible with safety, integrate these practices as contextual support; always clarify that they are not disease therapies. | Fully patient-led; encourage if meaningful to well-being and not harmful or substitutive. | Patient prayer, mindfulness meditation, attendance at religious services |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de Alencar, J.N.; Rego, F.; Nunes, R. Integrating Morality and Science: Semi-Imperative Evidentialism Paradigm for an Ethical Medical Practice. Philosophies 2025, 10, 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies10060115

de Alencar JN, Rego F, Nunes R. Integrating Morality and Science: Semi-Imperative Evidentialism Paradigm for an Ethical Medical Practice. Philosophies. 2025; 10(6):115. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies10060115

Chicago/Turabian Stylede Alencar, José Nunes, Francisca Rego, and Rui Nunes. 2025. "Integrating Morality and Science: Semi-Imperative Evidentialism Paradigm for an Ethical Medical Practice" Philosophies 10, no. 6: 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies10060115

APA Stylede Alencar, J. N., Rego, F., & Nunes, R. (2025). Integrating Morality and Science: Semi-Imperative Evidentialism Paradigm for an Ethical Medical Practice. Philosophies, 10(6), 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies10060115