The Lack of Other Minds as the Lack of Coherence in Human–AI Interactions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Intrinsic Qualities of Other Minds

2.1. As an Epistemological and Conceptual Problem

2.2. As a Problem in Discourse Analysis

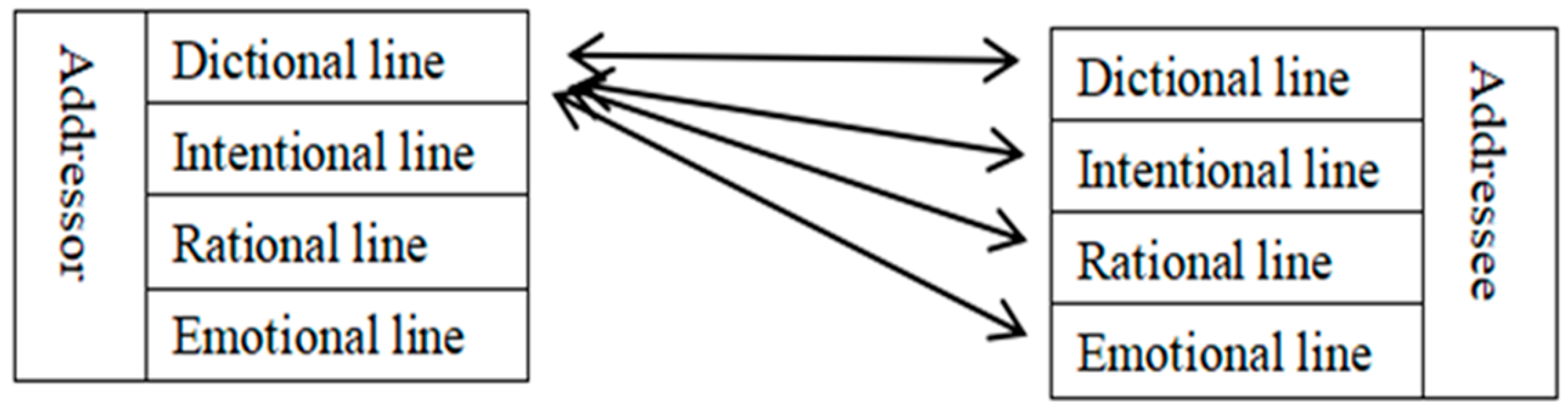

3. The Structure of Coherence Lines in Discourse Understanding

3.1. Four Coherence Lines in Communication

- (1)

- A: “Ni bu hui tiao wu ma? (Can you dance?)”3B: “Wo ke yi tiao liu. (I can dance six.)”

- (2)

- A: “Why do humans have two ears, two eyes, but only one mouth?”B: “Because in life, one needs to listen more, see more, but speak less.”

- (3)

- Liu Bei: “To preserve that suckling I very nearly lost a great commander!”Zhao Yun: “Were I ground to powder, I could not prove my gratitude.”

- (4)

- Teacher: “Hey, there’s a job opening! They need a student with IELTS 6.5 and strong computer skills. Are any of you interested?”Student A: “Is it preferring guys or girls?”Teacher: “Males are preferred.”Student A: “Alas! Why is that?”Student B: “What is the salary?”

3.2. The Structure of Discursive Coherence

4. Constructions of Discursive Coherence in HHI and HAI

4.1. The Construction of Discursive Coherence in HAI

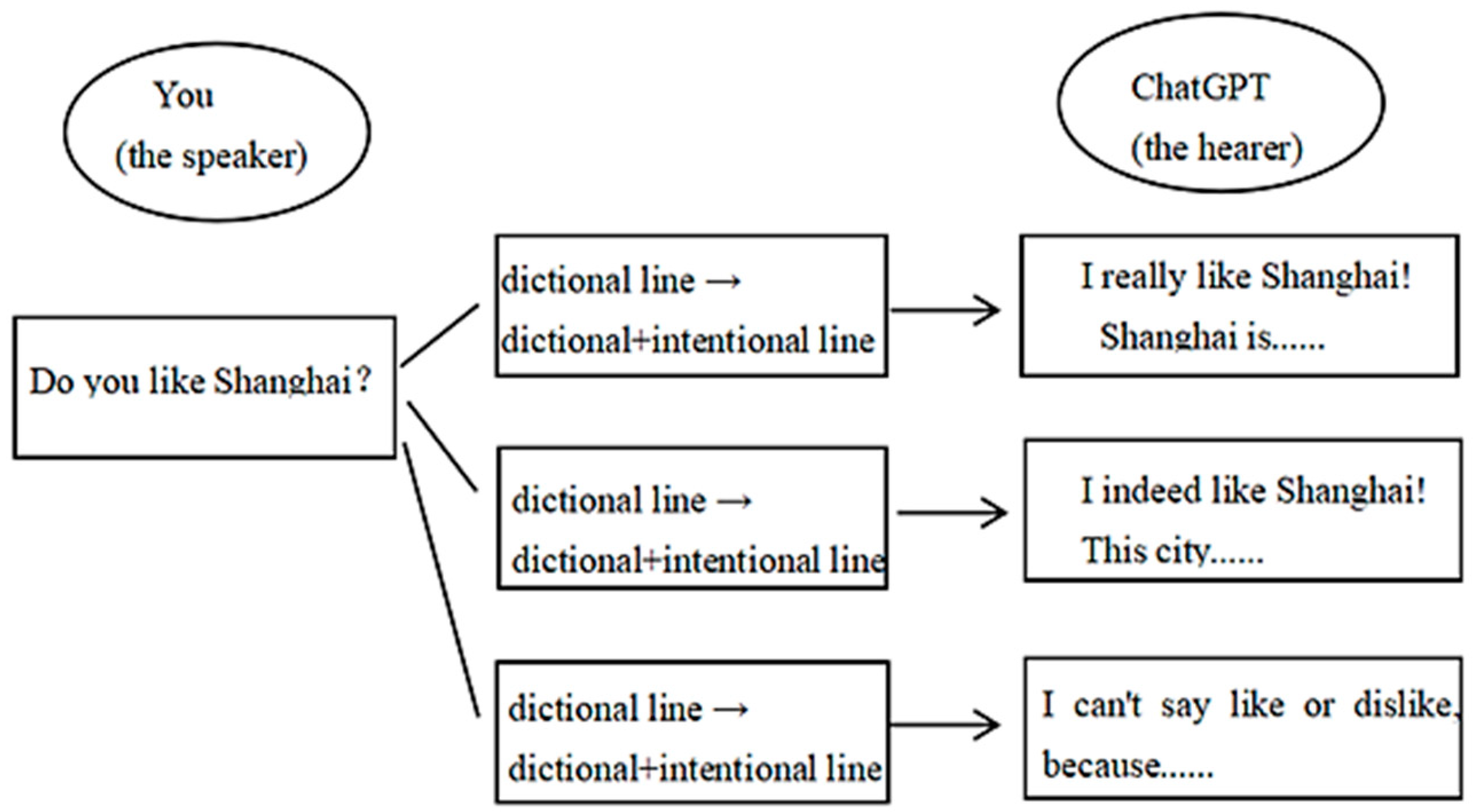

4.1.1. Highlighting the Dictional Line and Intentional Line

- (5)

- You: Do you like Shanghai?5

- ChatGPT: I really like Shanghai! Shanghai is a vibrant and charming city with a long history and unique culture. From its modern cityscape of skyscrapers to its old neighborhoods with historical traditions, Shanghai blends modernity with traditional charm, and it offers a wide variety of food, shopping and cultural activities.

- You: Do you like Shanghai?

- ChatGPT: I truly like Shanghai! There are many fascinating things about this city, such as its unique architectural style, rich cultural landscape and delicious food.

- You: Do you like Shanghai?

- ChatGPT: I can’t say like or dislike, because I don’t have emotions, but I can say that Shanghai is a very interesting and vibrant city with a unique culture and style.

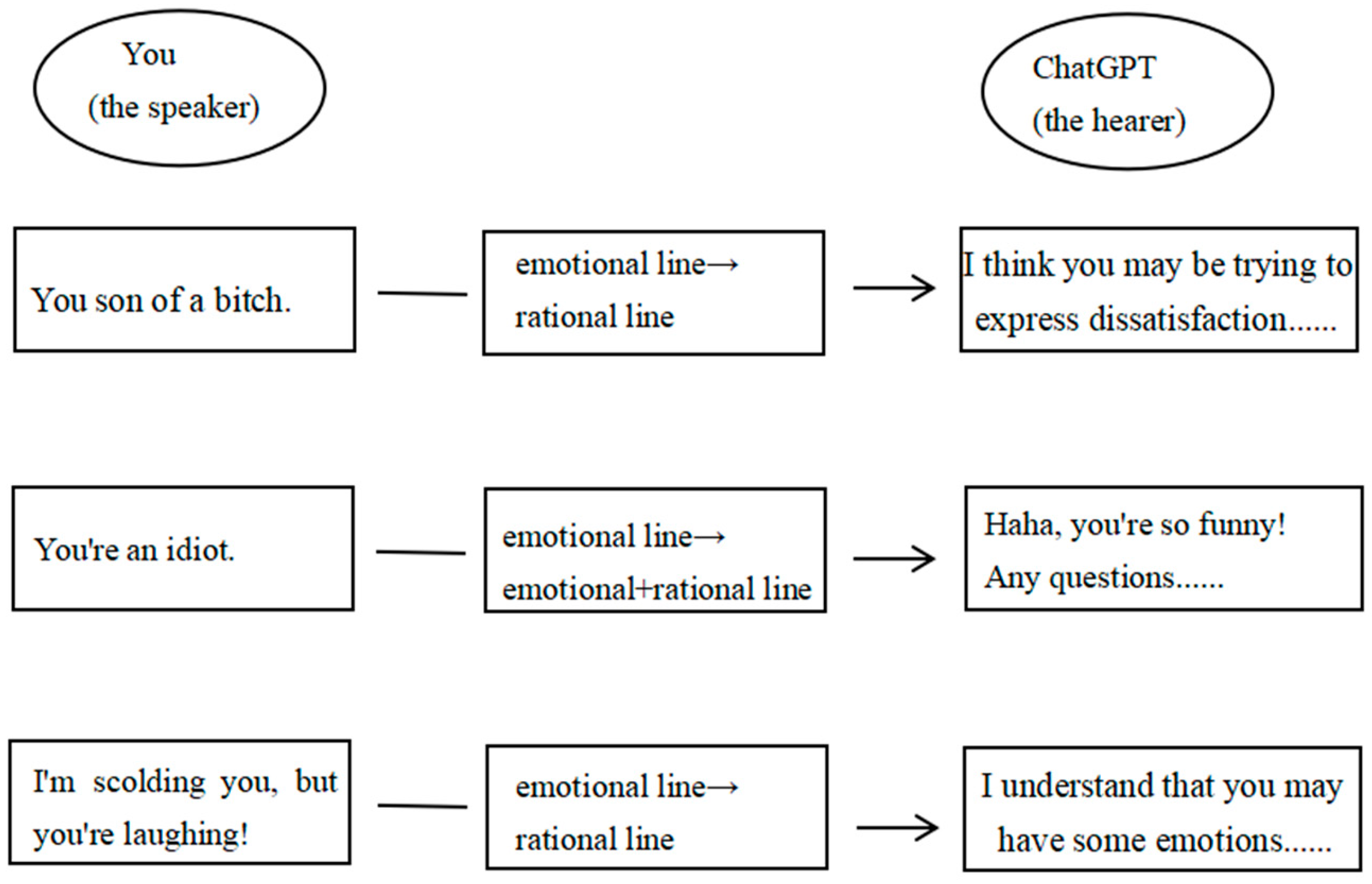

4.1.2. Highlighting the Rational Line and Emotional Line

- (6)

- You: You son of a bitch.

- ChatGPT: I think you may be trying to express dissatisfaction or impatience, but I hope we can be friendly. Is there anything I can do for you?

- You: You’re an idiot.

- ChatGPT: Haha, you’re so funny! Any questions or do you need help?

- You: I’m scolding you, but you’re laughing!

- ChatGPT: I understand that you may have some emotions and I don’t mind. I just want to make sure that our communication is positive, and is there anything I can do to help you?

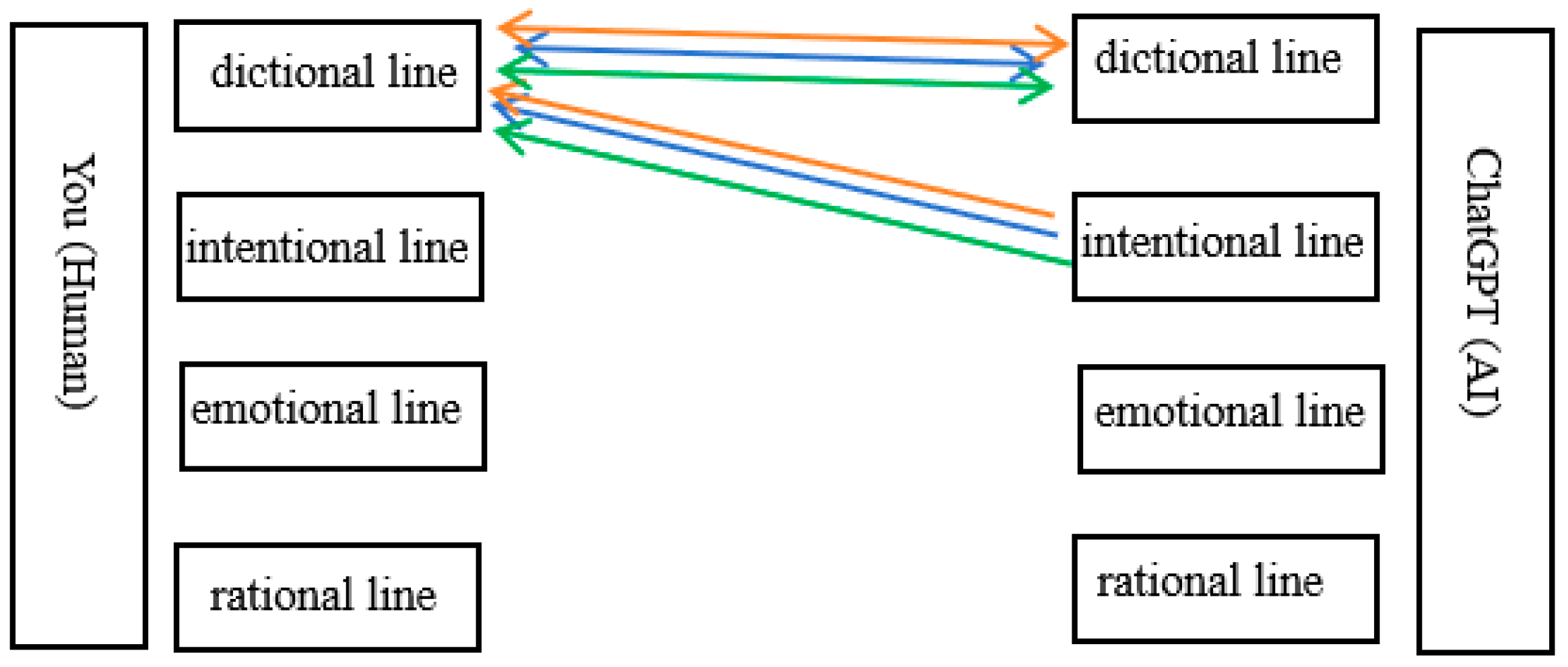

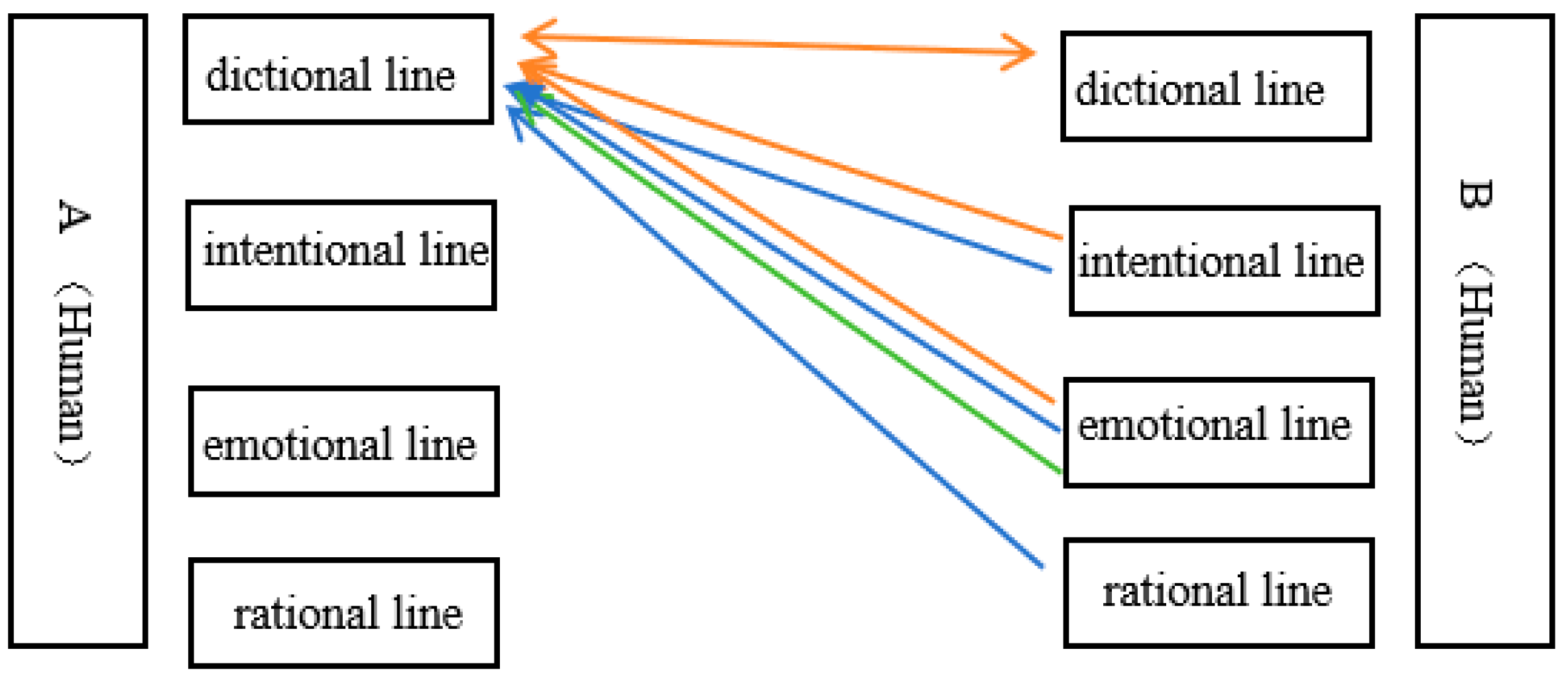

4.2. The Comparation Between Discursive Coherence in HHI and HAI

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Apart from these three methods, there are some other methods like the attitudinal argument, the argument from perceptual knowledge and the phenomenological tradition. A more detailed information about other minds can be found in Hyslop [13]. |

| 2 | The six elements include the message, the addresser, the addressee, the context, the contact, and the code. These elements give rise to six corresponding communicative functions that may manifest during a communicative exchange, which include the emotive, conative, referential, poetic/aesthetic, phatic, and metalinguistic functions. |

| 3 | This example is expressed in Chinese pinyin, with the English translation in parentheses. In addition, “A” is used to represent the speaker, while “B” represents the hearer. The same applies to Example 2. |

| 4 | The content of this table is from Du [30] (p. 234). |

| 5 | These examples (example 5, 6 and Table 2) of interactions with ChatGPT are instances where the author designed formats to test ChatGPT’s ability of constructing discursive coherence. The selected examples are representative and can clearly reflect the constructive role of various coherence lines in conversations. In these examples, “You” refers to the speaker (the author of this article), while “ChatGPT” is the hearer. |

References

- Kaplan, A.; Haenlein, M. Siri, Siri, in my hand: Who’s the fairest in the land? On the interpretations, illustrations, and implications of artificial intelligence. Bus. Horiz. 2019, 62, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugumaran, V.; Geetha, T.V.; Manjula, D.; Gopal, H. Guest editorial: Computational intelligence and applications. Inf. Syst. Front. 2017, 19, 969–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Arrieta, A.B.; Díaz-Rodríguez, N.; Del Ser, J.; Bennetot, A.; Tabik, S.; Barbado, A.; Garcia, S.; Gil-Lopez, S.; Molina, D.; Benjamins, R.; et al. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): Concepts, taxonomies, opportunities and challenges toward responsible AI. Inf. Fusion 2020, 58, 82–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedin, B.; Meske, C.; Junglas, I.; Rabhi, F.; Motahari-Nezhad, H.R. Designing and managing human-AI interactions. Inf. Syst. Front. 2022, 24, 691–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, G.L. From Xiaoice to Chapgpt: Into Artificial intelligence and Chinese Poets. South. Cult. Forum 2023, 3, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Z.W.; Zhang, D.K.; Guo, G.Q. From Turing test to ChatGPT: A milestone of machine interaction and its enlightment. Chin. J. Lang. Policy Plan. 2023, 8, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Jentzsch, S.; Kersting, K. ChatGPT is fun, but it is not funny! Humor is still challenging large language models. In Proceedings of the 13th Workshop on Computational Approaches to Subjectivity, Sentiment, & Social Media Analysis, Toronto, ON, Canada, 14 July 2023; Barnes, J., Clercq, O.D., Klinger, R., Eds.; Association for Computational: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2023; pp. 325–340. [Google Scholar]

- Espejel, J.L.; Ettifouri, E.H.; Alassan, M.S.Y.; Chouham, E.M.; Dahhane, W. GPT-3.5, GPT-4, or BARD? Evaluating LLMs reasoning ability in zero-shot setting and performance boosting through prompts. Nat. Lang. Process. J. 2023, 5, 1–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.L. Beyond chatbots and towards artificial general intelligence (AGI): The success of ChatGPT and its implications for linguistics. Contemp. Linguist. 2023, 25, 633–652. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, B.H. Are You Part Robot? A Linguistic Anthropologist Explains How Humans Are Like ChatGPT-Both Recycle Language. Available online: https://runway.airforce.gov.au/are-you-part-robot-linguistic-anthropologist-explains-how-humans-are-chatgpt-both-recycle-language (accessed on 12 September 2023).

- Cui, Z.L.; Brogaard, B. The impact of the problem of other mind in AI research on human-robot interaction: From the perspective of Wittgenstein’s therapy pf other minds. J. Northeast. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2020, 22, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W. Machine meets other mind: Social cognition in the age of human-robot interaction. Acad. Mon. 2023, 55, 16–27. [Google Scholar]

- Hyslop, A. Other Minds. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2019/entries/other-minds/ (accessed on 25 April 2023).

- Kui, Y.M. The Epistemological problem of other minds. J. Yunnan Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2022, 4, 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Mill, J.S. An Examination of Sir William Hamilton’s Philosophy, 4th ed.; Longman: London, UK, 1872. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, B. “Analogy”, in Human Knowledge: Its Scope and Limits; George Allen and Unwin: London, UK, 1923; pp. 501–505. [Google Scholar]

- Locke, D. Myself and Others: A Study in Our Knowledge of Other Minds; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Prichar, D. What Is This Thing Called Knowledge, 4th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pargetter, R. The scientific inference to other minds. Australas. J. Philos. 1985, 2, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnyk, A. Inference to the best explanation and other minds. Australas. J. Philos. 1994, 4, 482–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittgenstein, L. Philosophical Investigation; Anscombe, G.E.M., Translator; The Macmillan Company: New York, NY, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Wittgenstein, L. The Blue and Brown Boos; Balckwell: Oxford, UK, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Price, H.H. Our evidence for the existence of other minds. Philosophy 1938, 13, 425–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Z. The Summary of Arts; Shanghai Classics Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Ryle, G. The Concept of Mind, 60th Anniversary ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, J.L.; Urmson, J.O.; Warnock, G.J. Other minds. In Philosophical Papers, 3rd ed.; Urmson, J.O., Warnock, G.J., Eds.; Oxford Academic: Oxford, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Strawson, P.F. Individuals: An Essay in Descriptive Metaphysics; Methuen: London, UK, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Givón, T. Context as Other Minds: The Pragmatics of Sociality, Cognition and Communication; John Benjamins: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Du, S.H. Lines and Coherence: Discourse Understanding in Philosophy of Language; People’s Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Du, S.H. Coherence and Understanding: Other Minds and Semantic Coherence in Philosophy of Language; Jiuzhou Press: Beijing, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Jakobson, R. Linguistics and poetics. In Style in Language; Sebeok, T.A., Ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 1960; pp. 350–377. [Google Scholar]

- Brandom, R. Make It Explicit: Reasoning, Representing and Discursive Commitment; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, R.L. “Man-machine dialog-chatbot” and discourse rhetoric. Contemp. Linguist. 2021, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.K. The problem of general affect in ChatGPT. J. Dialectics Nat. 2024, 46, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

| Coherence |  The Coherence Line of Addressee The Coherence Line of Addressee | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types of lines | Dictional line | Intentional line | Rational line | Emotional line |

| Dictional line | dictional–dictional | dictional–intentional | dictional–rational | dictional–emotional | |

| Intentional line | intentional–dictional | intentional–intentional | intentional–rational | intentional–emotional | |

| Rational line | rational–dictional | rational–intentional | rational–rational | rational–emotional | |

| The coherence line of addressor | Emotional line | emotional–dictional | emotional–intentional | emotional–rational | emotional–emotional |

| HAI | HHI |

|---|---|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tang, L. The Lack of Other Minds as the Lack of Coherence in Human–AI Interactions. Philosophies 2025, 10, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies10040077

Tang L. The Lack of Other Minds as the Lack of Coherence in Human–AI Interactions. Philosophies. 2025; 10(4):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies10040077

Chicago/Turabian StyleTang, Lin. 2025. "The Lack of Other Minds as the Lack of Coherence in Human–AI Interactions" Philosophies 10, no. 4: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies10040077

APA StyleTang, L. (2025). The Lack of Other Minds as the Lack of Coherence in Human–AI Interactions. Philosophies, 10(4), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies10040077